Abstract

Background

Client satisfaction is an important method to assess the pattern of utilization of health care services amongst all sectors indirectly reflecting on the quality of services. Most of the clients prefer private over government services due to multiple reasons.

Aim

To assess the level of satisfaction of patients attending rural government and private health facilities in rural Andhra Pradesh.

Methods

Ten villages were randomly selected from the field practice area of a teaching medical institution, and all patients who visited any facility during the past three months were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire focusing on access to care, competence of the providers, quality and cost of the services and overall satisfaction with the services. Data was analysed using Microsoft Access software.

Results

One hundred and eight clients who visited different facilities for common ailments, chronic diseases, maternal and child health services were interviewed. The average time to reach the facility was 52.23 ± 44.52 minutes. The average waiting time was 34.25 ± 42.47 minutes. More than 80% were satisfied with the clinic hours, cleanliness and comfort of the facility, and privacy maintained during examinations. 40% were satisfied with the cost of services.

Conclusion

The client satisfaction with different health care providers in rural areas of Andhra Pradesh is high. Clients expect the quality of services to be better; nevertheless they continue to use the available services without complaining much.

Keywords: Client satisfaction, quality, health care services, private, government, cost

Introduction

Quality of health care in developing countries, borrowing mainly from findings in developed countries, has gained increased attention in recent years, wherein outcomes have received special emphasis as a measure of quality. Assessing outcomes has merits as an indicator of the effectiveness of different interventions on one hand, and as part of a monitoring system directed to improving quality of care as well as detecting its deterioration on the other (Aldana et al., 2001; Epstein, 1990). Quality assessment studies usually measure costs, medical outcomes or client satisfaction. For client satisfaction assessment, clients are not only asked to assess their health status after receiving care, but also their satisfaction with the services received (Fisher, 1971). Characteristics of the health care providers and services that influence patient satisfaction were proposed by Ware et al., whose dimensions included: art of care (caring attitude); technical quality of care; accessibility and convenience; finances (ability to pay for services); physical environment; availability; continuity of care; efficacy and outcome of care (Ware et al., 1977). A working definition of patient satisfaction is the degree to which the patient’s desired expectations, goals or preferences are met by the health care provider or the service (Debono et al., 2009).

In accordance with the suggestions of international bodies to improve quality of care (De Geydnt, 1995), the National Rural Health Mission in India recommended a thorough organizational restructuring of the entire primary health care sector with the aim of establishing health care services that are more sustainable, cost-effective, and responsive to client needs (Government of India, 2005).

Previous assessments of client satisfaction with services have usually focused on a marginal element in performance appraisals and have mostly been limited to maternal and child health (Kumari et al., 2009; Patro et al., 2008). Published literature reflects the results of exit interviews conducted at the government facilities, and therefore fails to provide a true picture about utilization of facilities depending on their quality. Moreover, there is dearth of studies mentioning about quality and patient satisfaction in the private sector (Ganguly et al., 2008). Therefore, the present study was designed with the objective to assess in detail the expectations of quality of care and the level of satisfaction of patients attending rural government and private health facilities. It was envisioned that better understanding of the determinants of client satisfaction would help policy-makers to implement programs suited to patients’ needs as perceived by patients.

Methodology

A cross sectional study was conducted in a rural area (Medchal mandal) of Rangareddy district in northern Andhra Pradesh state of India from 1st March through 18th July 2011. The population of this area, approximately 50,000, is primarily rural, engaged in agriculture, and literate up to the primary level of schooling as per our last household census (2010) findings. Most of the women are housewives. Health care services in the area comprise of several private hospitals and clinics providing allopathic and ayurvedic treatments, a tertiary care teaching medical institution, two Primary health centres and a district hospital (tertiary level) run by the government, and faith healers with no formal medical training. Ethical clearance for conducting the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

The teaching medical institution maintains a computerized data base of family socio-demographic and health information (updated monthly) for every household in the 42 villages in its field practice area. Ten large villages (hamlets having <500 population were merged into nearest large village and selected) were randomly selected using a computer generated random number table from these forty two villages in the sampling frame to cover at least 20% sample for qualitative study. All households were surveyed to identify the participants who visited any health facility within the past three months. The consenting selected participants in these households, or the primary caretaker where participant was a child aged less than 12 years, were interviewed by two trained investigators using a semi-structured questionnaire. One day training for the investigators in administering the questionnaire and the study protocol was done in the department of community medicine by the authors.

Information was collected using a predesigned and pretested questionnaire. The reliability and validity of the semi-structured questionnaires, as well as the reliability of the entire process of data collection, was tested by the authors outside the study area before the study was carried out. This was done through a pilot study in a nearby village outside the sampling frame upon 20 visitors of any health care facility belonging to different age groups chosen according to feasibility. The questionnaire was translated in local language and then back translated in english for validity testing. Interviews were performed outside the house, and confidentiality of the information gathered was assured. Informed consent was obtained verbally from each included participant.

Services sought by clients were divided into five categories: common diseases, chronic diseases/follow up, maternal care, child care and others. Clients were asked to supply the following information about themselves: age, sex, occupation, time taken to travel to health facilities, means of transport, care-seeking preferences, expectations and level of satisfaction related to waiting and consultation time. They were also asked about various aspects related to providers’ technical competence during consultations which included determining whether the service provider had asked why the client had presented for consultation, whether the client had been supplied with a description of the nature of his or her health problem, whether the client’s privacy had been respected, whether a physical examination had been conducted, whether advice had been given and overall behavior of the provider.

Level of satisfaction was assessed in two steps. First, users were asked whether or not they were satisfied with the care received, and then they were asked about their level of overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction. During field testing, this method proved to give more reliable and accurate information of four levels of satisfaction (very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied) than a direct assessment.

The collected data was entered in Microsoft excel and analysed using Microsoft Access software. Descriptive statistics for different variables under study are being reported in the present paper.

Results

A total of 108 participants were interviewed out of 110 who visited a health facility in the preceding three months, giving a response rate of 98.18%, of which 52.78% were female respondents whose mean age was 23.53 ± 6.74 years, whereas 47.22% were males having mean age 25.92 ± 9.67 years. 8.33% were children under 5 years of age. Most of the females were employed in agricultural labor or household work, whereas men mostly worked as industrial laborers or in their own fields (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background information of the users of different health facilities in rural Medchal mandal

| Variable | Male (n=51) | Female (57) | Total N=108 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <5 years | 6 (11.76) | 3 (5.26) | 9 (8.33) |

| 5–15 years | 17 (33.33) | 12 (21.05) | 29 (26.85) | |

| 15–45 years | 19 (37.25) | 28 (49.12) | 47 (43.52) | |

| >45 years | 9 (17.65) | 14 (24.56) | 23 (21.30) | |

| Occupation | Agricultural labourer | 6 (11.76) | 32 (56.14) | 38 (35.18) |

| Farmer | 7 (13.73) | 3 (5.26) | 10 (9.26) | |

| Industrial labourer | 22 (43.14) | 2 (3.51) | 24 (22.22) | |

| Service | 4 (7.84) | - | 4 (3.70) | |

| Household work | - | 19 (33.33) | 19 (17.59) | |

| Other | 6 (11.76) | 1 (1.75) | 7 (6.48) | |

Figures in parentheses indicate percentages.

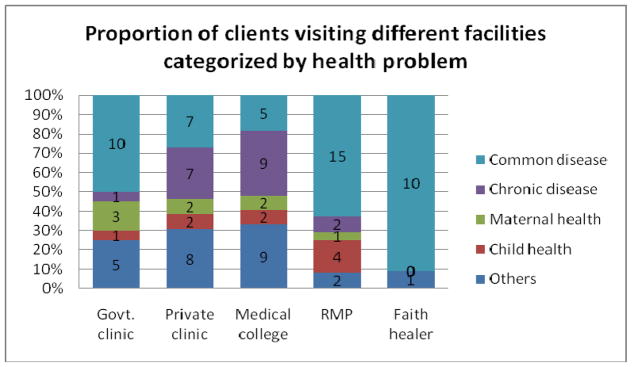

Satisfaction with access to health care

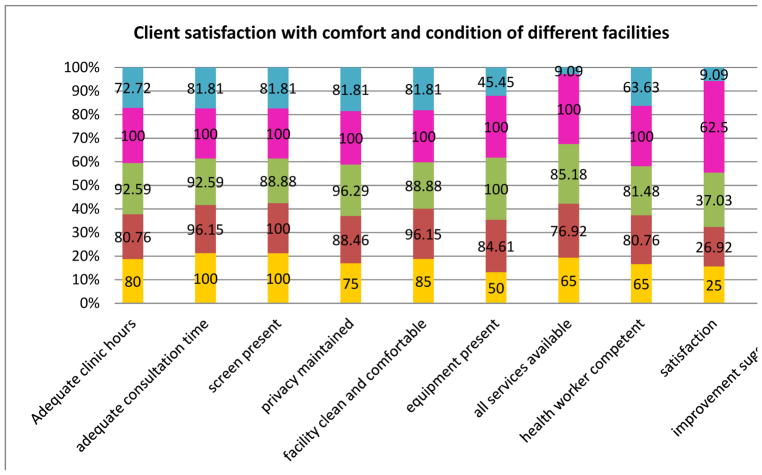

The majority (75.00%) of clients reported living close to the health facilities, and 32.41% reported that they were able to reach the facility within 30 minutes. The average time to reach the facility was 52.23 ± 44.52 minutes. About half (54%) of the clients preferred bus as means of transport. The average waiting time at the facilities was 34.25 ± 42.45 minutes, with about 51% of the clients having to wait 40 minutes to an hour for seeing a doctor (Table 2). 53.70% of clients reported visiting the health facilities regularly for their different health problem, the highest preference (91%) being for local Registered Medical Practitioners (RMP) and the least (25%) for government facilities (Fig. 1), which was significant (p<0.05). A large proportion of the clients (more than 80%) felt that the clinic hours were adequate for their needs, and that the doctors devoted sufficient time to listen to their health problems, though the users of government facilities fared behind the users of private facilities (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Client satisfaction with access to health care in rural Medchal mandal

| Variable | Type of facility | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government clinic/hospital (n=20) | Private clinic/hospital (n=26) | Medical college (n=27) | Local Registered Medical Practitioner (n=24) | Other Faith healers (n=11) | N=108 | ||

| Reason for visiting facility last time | Common disease | 10 (50.00) | 7 (26.92) | 5 (18.51) | 15 (62.5) | 10 (90.90) | 47 (43.52) |

| Chronic disease | 1 (5.00) | 7 (26.92) | 9 (33.33) | 2 (8.33) | - | 19 (17.59) | |

| Maternal health | 3 (15.00) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (7.40) | 1 (4.16) | - | 8 (7.40) | |

| Child health | 1 (5.00) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (7.40) | 4 (16.66) | - | 9 (8.33) | |

| Others | 5 (25.00) | 8 (30.76) | 9 (33.33) | 2(8.33) | 1 (9.09) | 25 (23.14) | |

| Distance from house hold | <30 min | 7 (35.00) | 3 (11.53) | 5(18.51) | 17 (70.83) | 3 27.27) | 35 (32.40) |

| 30min–1hr | 8 (40.00) | 14(53.84) | 16(59.25) | 7 (29.16) | 8(72.72) | 53 (49.07) | |

| >1hr | 5 (25.00) | 9 (34.61) | 6 (22.22) | - | - | 20 (18.50) | |

| Facility visited regularly | 5 (25.00) | 13(50.00) | 17(62.96) | 22(91.66) | 1(9.09) | 58 (53.70) | |

| Ability to reach facility easily | 13 (65.00) | 20(76.92) | 20(74.07) | 24 (100.00) | 4(36.36) | 81 (75.00) | |

| Time taken to reach facility | 5–20 min | 7 (35.00) | 3 (11.53) | 5 (18.51) | 17 (70.83) | 3(27.27) | 35 (32.40) |

| 30min–1hr | 8 (40.00) | 14(53.84) | 16(59.25) | 7 (29.16) | 8(72.72) | 53 (49.07) | |

| >1hr | 5 (25.00) | 9 (34.61) | 6 (22.22) | - | - | 20 (18.50) | |

| Mode of transport used to reach facility | Ambulance | - | - | 1 (3.70) | - | - | 1 (0.93) |

| Auto rickshaw | 3 (15.00) | 2 (7.69) | 3 (11.11) | - | 1 (9.09) | 9 (8.33) | |

| Bus | 14 (70.00) | 16(61.53) | 12(44.44) | 5 (20.83) | 8(72.72) | 55 (50.90) | |

| Other Vehicle | 2 (10.00) | 6 (23.07) | 11(40.74) | 2 (8.33) | - | 21 (19.44) | |

| Walk | 1 (5.00) | - | - | 17 (70.83) | 1 (9.09) | 19 (17.59) | |

| Waiting time | <30 min | 12 (60.00) | 8 (30.76) | 7 (25.92) | 19 (79.16) | 1 (9.09) | 47(43.52) |

| 30min–1 hr | 7 (35.00) | 14(53.84) | 19(17.37) | 5 (20.83) | 10(90.9) | 55(50.93) | |

| 1–2 hr | 1 (5.00) | 4 (15.38) | 1 (3.70) | - | - | 6 (5.55) | |

Figures in parentheses indicate percentages.

Figure 1.

Proportion of clients visiting different health facilities categorized by health problem in rural Medchal mandal

Figure 2.

Client Satisfaction with comfort and services present at different facilities in rural Medchal mandal

Satisfaction with Competence of health care providers

The proportion of providers who asked the patients their reasons for attending the facility was relatively high (72.8%), but providers gave advice to only 23.8% of clients, and explained the nature of their health problem only to 12.2%. This was much less (4.34%) for patients attending Government facilities. A physical examination was performed on only 37% of all patients. Privacy during physical examination was reported to be maintained for 89.81% of these clients. No significant differences were found among health facilities, but providers were said to have performed physical examinations on 78.46% of patients presenting for antenatal care, compared to 21.54% of clients coming for other health problems. Still 80.55% of the clients expressed satisfaction with the competence of the health care providers that they visited (Fig. 2).

Users’ satisfaction with the services

A total of 35% of patients expressed satisfaction with the services rendered to them. Most of the clients (more than 80%) were satisfied with the comfort and cleanliness of the clinics and availability of equipment and services at the facilities (Fig. 2). Only a meager 6.48% suggested some improvements in the existing health facilities, like providing all required medicines at the government facility, reimbursing the expenditure incurred for doing tests not available at the government facility, reducing the user charges and increasing the consultation time to suit their needs. About 88% of the clients paid user fees for utilizing the services, the highest proportion comprising of private hospitals and RMPs. 41.67% of the participants felt that the present cost of the services was affordable for most of the families in the villages. However, only 39.81% were happy with cost of the services, and 24% were not happy (Table 3). Only 19% clients expressed the willingness to pay more for the services if the suggested improvements were made.

Table 3.

Client Satisfaction with cost of services at different facilities in rural Medchal mandal

| Variable | Type of Facility | Total (N=108) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government clinic/hospital (n=20) | Private clinic/hospital (n=26) | Medical college (n=27) | Local Registered Medical Practitioners (n=24) | Other Faith healers (n=11) | |||

| Paying for services | 9 (45.00) | 26(100.00) | 27(100.00) | 24 (100.00) | 9(81.81) | 95(87.96) | |

| Happiness with cost of service | Extremely happy | - | - | - | 1 (4.16) | 1 (9.09) | 2 (1.55) |

| Happy | 5 (25.00) | 4 (15.38) | 14 (51.85) | 20 (83.33) | - | 43(39.81) | |

| Managable | 9 (45.00) | 13 (50.00) | 7 (25.92) | 3 (12.50) | 3(27.27) | 35(32.40) | |

| Not Happy | 4 (20.00) | 9 (34.61) | 6 (22.22) | - | 7(63.63) | 26(24.07) | |

| Can’t say | 2 (10.00) | - | - | - | - | 2 (1.85) | |

| Affordability for Families in villages | Yes | 5 (25.00) | 4 (15.38) | 16 (59.25) | 19 (79.16) | 9(81.81) | 45(41.67) |

| No | 7 (35.00) | 8 (30.76) | 5 (18.51) | - | 1 (9.09) | 21 (19.44) | |

| Don’t know | 8 (40.00) | 14 (53.85) | 6 (22.22) | 5 (20.83) | 1 (9.09) | 34 (31.40) | |

| Willingness to pay more if suggested improvements are made | Yes | 5 (25.00) | 6 (23.08) | 7 (25.93) | 6 (25.00) | 5(45.45) | 29(26.85) |

| No | 7 (35.00) | 8 (30.76) | 13 (48.14) | 12 (50.00) | 4(36.36) | 44 (4.07) | |

| Don’t know | 8 (40.00) | 12 (46.15) | 7 (25.92) | 6 (25.00) | 2(18.18) | 35 (32.40) | |

Figures in parentheses indicate percentages.

Discussion

The results of the present study show high levels of client satisfaction with the different available health services in a rural area of Andhra Pradesh. Clientele in different facilities is determined by specific services provided, and hence, the reasons for visiting different facilities among the rural population also determines which facility they visit, e.g. the clients visited government facilities mostly to avail maternal and child health care, whereas private facilities were sought for common ailments. The difference between the number of users of government and private facilities was found to be significant in our study. Similar findings have been reported from other Indian states (Kumari et al., 2009; Patro et al., 2008; Das et al., 2010) and neighbouring countries (Aldana et al., 2001; Fisher, 1971) as well where the use of government facilities is limited to maternal and child health services with low levels of satisfaction.

When looking at the clients’ perception of satisfaction with competence of the health care providers in the present study, we found that most of the parameters of competence were not complied with by providers in both government and private institutions. These parameters were: asking for main presenting complaints or reason of visit to clinic, taking proper history, thorough examination of the patients, writing a prescription, explaining the prescription, providing preventive advice and providing follow up dates. Similar findings have been reported from other states as well (Kumari et al., 2009; Patro et al., 2008; Ganguly et al., 2008; Das et al., 2010), indicating the need to improve upon these competencies, the absence of which might be a major deterrent to availing the facilities. These studies, concordant to our findings, have reported high client satisfaction with asking chief complaints and the degree of privacy maintained during physical examination. A recent study (Kumar et al., 2012) reported 94.9% clients to be satisfied with physicians and 88.2% satisfied with cleanliness services in private facilities in North India, which is similar to the present study findings. Another study (Sodani et al., 2010) of 561 clients attending the government facilities in a central Indian state reported higher proportion of clients (91%) to be satisfied with the public health care services, against 65% in the present study from rural Andhra Pradesh.

The overall patient satisfaction from services in rural areas appears to be high. The Government of India studied three states of Haryana, Orissa and Uttar Pradesh and found 51.22% of the beneficiaries to be dissatisfied with the functioning of PHCs with reasons for dissatisfaction being similar to the present findings of non availability of clean infrastructure, medicines, laboratory services, and not being properly examined by the doctors (Government of India, 2001).

We found that only about 40% of the clients were happy with cost of the services, and of them, about 19% clients were willing to pay more for the services provided the suggested improvements were included. This is much lower compared with study findings from three northern states of Haryana, Orissa and Uttar Pradesh (Government of India, 2001), where as many as 68.2% were willing to pay more for services that were provided at the Primary Health Centres if the suggested improvements were made. Other studies (Prasanna et al., 2009) have reported 94% of the clients attending medical colleges for services being satisfied with the cost of services compared to 78% in our study. They have also reported high satisfaction levels with the physicians’ competence which is comparable to our findings.

Conclusion

The overall client satisfaction with the available health care services in rural areas of Andhra Pradesh is high. A detailed analyses of individual components of quality highlights that competence of the health care providers and cost of the services are two major areas of dissatisfaction, which is more in case of government providers than private. Clients however, continue to use these facilities without much complaining due to the affordability of these services, and lack of access to better quality health care.

Recommendations.

More studies of this kind are needed to bring out the cross cultural differences and patterns of utilization of different health services across the country. Based on findings of the present study, the government hospitals, private hospitals and medical colleges need to improve specific parameters which encourage the clients for visiting untrained local practitioners such as waiting time, accessibility, approach to the health problem and cost, in order to improve their clientele and satisfaction with services and reduce the health related risks among them.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the investigators for data collection and the respondents for participating in this study.

References

- Aldana JM, Piechulek H, Ahmed Al-Sabir A. Client satisfaction and quality of health care in rural Bangladesh. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001;79:512–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Basu M, Tikadar T, Biswas GC, Mridha P, Pal R. Client satisfaction on Maternal and Child Health Services in Rural Bengal. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:478–481. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.74344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debono D, Travaglia J. Complaints and patient satisfaction: a comprehensive review of the literature. Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health, UNSW; 2009. [Accessed on November 22, 2012]. Available from URL: http://www.health.vic.gov.au/clinicalengagement/downloads/pasp/literature_review_patient_satisfaction_and_complaints.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- De Geydnt W. Managing the quality of health care in developing countries. Washington, DC: the World Bank; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A. Sounding board: the outcomes movement, will it get us where we want to go? New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323:266–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AW. Patient’s evaluation of outpatient medical care. Journal of Medical Education. 1971;46:238–244. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly E, Deshmukh P, Garg BS. Quality assessment of private practitioners in rural Wardha, Maharashtra. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:35–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.39241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. Evaluation Study on Functioning of Primary Health Centres(PHCs) Assisted under Social Safety Net Programme (SSNP) Programme Evaluation Organisation, Planning Commission, Government of India; New Delhi: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Haque A, Tehrani HY. High Satisfaction Rating by Users of Private-for-profit Healthcare Providers—evidence from a Cross-sectional Survey Among Inpatients of a Private Tertiary Level Hospital of North India. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:405–10. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.100991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Idris M, Bhushan V, Khanna A, Agarwal M, Singh S. Study on patient satisfaction in the government allopathic health facilities of Lucknow district, India. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:35–42. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.45372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Rural Health Mission. [Accessed on November 22, 2012];Indian Public Health Standards. 2005 Available from URL: http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/iphs.htm.

- Patro BK, Kumar R, Goswami A, Nongkynrih B, Pandav CS UG Study Group. Community perception and client satisfaction about the primary health care services in an urban resettlement colony of New Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:250–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.43232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna KS, Bashith MA, Sucharitha S. Consumer satisfaction about hospital services: A study from the outpatient department of a private medical college hospital at Mangalore. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:156–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.51220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodani PR, Kumar RK, Srivastava J, Sharma L. Measuring Patient Satisfaction: A Case Study to Improve Quality of Care at Public Health Facilities. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:52–56. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Davies-Avery A, Stewart A. [Accessed on November 22, 2012];The Measurement and Meaning of Patient Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. 1977 Available from URL: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2008/P6036.pdf. [PubMed]