Abstract

Background & Aims

There is little evidence that adiposity associates with diverticulitis—especially among women. We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of obesity, weight change, and incidence of diverticulitis in a large cohort of women.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of 46,079 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study, 61–89 years old and free of diverticulitis, diverticular bleeding, cancers, or inflammatory bowel disease at baseline (in 2008). We used Cox proportional hazards models to examine the associations between risk of incident diverticulitis and body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist to hip ratio, and weight change from age 18 years to the present. The primary endpoint was first incident diverticulitis requiring antibiotic therapy or hospitalization.

Results

We documented 1084 incident cases of diverticulitis over 6 years of follow up, encompassing 248,001 person-years. After adjustment for other risk factors, women with a BMI ≥ 35.0 kg/m2 had a hazard ratio (HR) for diverticulitis of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.08–1.85) compared to women with a BMI < 22.5 kg/m2. Compared to women in the lowest quintile, the multivariable HRs among women in the highest quintile were 1.35 (95% CI, 1.02–1.78) for waist circumference and 1.40 (95% CI, 1.07–1.84) for waist to hip ratio; these associations were attenuated with further adjustment for BMI. Compared to women maintaining weight from age 18 years to the present, those who gained 20 kg or more had a 73% increased risk of diverticulitis (95% CI, 27%–136%).

Conclusions

Over a 6-year follow-up period, we observed an association between obesity and risk of diverticulitis among women. Weight gain during adulthood was also associated with increased risk.

Keywords: overweight, colon, inflammation, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Diverticulitis, or acute inflammation of colonic diverticula, is associated with acute and chronic complications. It is among the leading gastrointestinal indications for hospitalization and outpatient clinical visits in the U.S.1, 2. Accumulating evidence suggests an association between dietary and lifestyle factors and disease development3–9.

Obesity is one of the major risk factors for a number of gastrointestinal diseases, including gastroesophageal reflux disease10, pancreatic disease11, 12, and colorectal cancer13, 14, possibly due to chronic inflammation and alterations in gut microbiota, proposed drivers in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis15. Several studies from our group and others have consistently demonstrated an association between higher body mass index (BMI) and increased risk of diverticulitis16 or diverticular disease requiring hospitalization or as the cause of death4, 17, 18. However, evidence on obesity and diverticulitis remains sparse for more common and mild presentations of this disease, especially among women. Beyond BMI, limited evidence suggests that visceral fat may be more important in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis16, 19, 20, but it is unclear whether abdominal adiposity, as assessed by waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), is also related to diverticulitis in women. Furthermore, the influence of weight change on incidence of diverticulitis remains poorly understood. Compared to studies of adult BMI, investigation of weight change may better capture the effect of excess body fat during adulthood.

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of obesity and incidence of diverticulitis in a large cohort of U.S. women, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The NHS began in 1976 with 121,700 U.S. female registered nurses aged 30 to 55 years at enrollment. Participants have been mailed questionnaires every two years since inception querying demographics, lifestyle factors, medical history, and disease outcomes, with a follow-up rate greater than 90% of available person-time. Details of the cohort have been described elsewhere21. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Assessment of Exposure

Participants were asked to report their height at enrollment and current body weight in biennial questionnaires. Recalled weight at age 18 years was inquired in 1980. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height squared in meters. In 1986, participants were asked to measure their waist at the umbilicus and hips at the largest circumference between their waist and thighs, while standing and relaxed. Waist and hip circumference information was updated using the same procedure in 1996 and 2000. Circumference measurements were recorded to the nearest quarter of an inch, and WHR was calculated for each set of circumferences. We assessed weight change from early adulthood (age 18 years) to updated weight as reported in the current questionnaire cycle, which represented long-term weight change from early adulthood22, 23. To evaluate the effect of recent weight change, in a secondary analysis, we assessed 4-year weight change during follow-up, which was calculated and updated using repeated weight assessments 4 years apart. We suspended updating weight change information when a participant quit smoking or reported a diagnosis of cancer, cardiovascular disease, or inflammatory bowel disease in the past 2 years to reduce the influence of unintentional weight change and confounding from shared risk factors22.

In a validation study among 140 women within the NHS cohort, self-reported weight, waist and hip circumference, and WHR were compared to the average of two measurements taken by technicians approximately 6 months apart. Self-reported and measured weight, WC, hip circumference, and WHR were highly correlated (correlation coefficients of 0.97, 0.89, 0.84, and 0.70, respectively)24. Recalled weight at age 18 has also shown high validity among 118 women within the parallel NHS II cohort, with a correlation coefficient of 0.87 between recalled and measured weight at age 1825.

Ascertainment of Outcome

In 2008 and 2012, participants were asked if they ever had a diagnosis of diverticulitis requiring antibiotic therapy or hospitalization as well as diverticular bleeding requiring blood transfusion and/or hospitalization. If yes, participants were subsequently asked the year of each episode dating back to 1990. In 2014, participants were asked the same question, but restricted to the last two years. In a review of 107 medical records from women reporting incident diverticulitis on the 2008 questionnaire, self-report was confirmed in 88% of cases. Recurrent diverticulitis was defined as cases with more than one episode of diverticulitis. In 2012 and 2014, participants were asked to report if they ever had surgery for diverticulitis. The primary endpoint was diverticulitis requiring antibiotic therapy or hospitalization, and we also included diverticular bleeding, recurrent diverticulitis, and surgery for diverticulitis as secondary outcomes.

Assessment of Covariates

Since baseline and updated biennially, information on smoking status, menopausal status and menopausal hormone use, physical examination, and use of multivitamin, aspirin, and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or acetaminophen was obtained. Physical activity was assessed every 2–4 years using validated questionnaires26. Hypertension and hypercholesterolemia were self-reported, and their validity previously confirmed27. Usual dietary habits were assessed every 4 years using validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires28.

Statistical Analysis

We restricted the analysis to participants who returned 2008, 2012, or 2014 questionnaires and restricted follow-up from 2008 to 2014 to ensure the cases were ascertained prospectively. We also excluded those who reported a diagnosis of diverticulitis, diverticular bleeding, non-melanoma cancers, or inflammatory bowel disease prior to 2008, or those with missing exposure information. Person-time was calculated from the date of return of the 2008 questionnaire until the date of diagnosis of diverticulitis or diverticular bleeding, death, last return of a valid follow-up questionnaire, or the end of follow-up (June 2014), whichever came first. We censored women who reported a new diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease at the date of diagnosis.

Cox proportional hazards models were applied to assess the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). To control for confounding by age, calendar time, and any possible two-way interactions between these two timescales, we stratified the analysis jointly by age in years at start of follow-up and calendar time of the current questionnaire cycle. Proportional hazards assumption was tested by including the product term between exposure variable and age, and testing significance by Wald test. No deviation from proportional hazards assumption was detected. We discretized BMI into 6 categories routinely used in clinical practice to define subgroups for overweight and obese subjects29. Quintiles were created to categorize WC and WHR, with the lowest quintile as a reference. We also created six categories of weight change from early adulthood to the present based on the observed distribution (median weight change: 12.7 kg): weight loss ≥ 2.0kg; loss or gain < 2.0 kg (reference); gain 2.0–5.9 kg; gain 6.0–9.9 kg; gain 10.0–19.9 kg; and gain ≥ 20.0 kg. These cutoffs were comparable with those used in prior studies23. Test for trend was assessed by assigning the median value for the sample to each category and modeling this as a continuous variable. We allowed exposures and covariates to be time-varying by updating and using the most recent information prior to the questionnaire cycle of interest to account for changes in these exposures and covariates over time. For example, BMI and covariates from the 2008 questionnaire was used to calculate the risk for the period from 2008 to 2010.

In multivariate analysis, we adjusted for menopausal status and menopausal hormone use, vigorous activity, alcohol intake, smoking, use of aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, or acetaminophen, multivitamin use, physical examination, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, calorie intake, dietary fiber intake, and red meat intake. In analysis of weight change, we additionally controlled for height and baseline weight. In our analysis of WC and WHR, we further controlled for height and BMI to explore the potential association independent of overall adiposity. We also classified participants jointly by BMI and WHR and assessed the association with diverticulitis. We conducted stratified analyses to evaluate whether the associations of BMI and weight change with diverticulitis varied by subgroups defined by age, physical activity, and smoking status. Test for interaction was performed by including the product term between BMI/weight change and the stratified variable into the model and testing the statistical significance using Wald test.

Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis by utilizing the full follow-up from 1990 to 2014 with the inclusion of cases that were reported on the 2008, 2012 and 2014 questionnaires with dates of the episode between 1990 and 2008. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All p-values are 2-sided and < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In 2008, the baseline characteristics associated with categories of BMI, WC, and WHR in the study participants are shown in Table 1. Women with higher BMI, WC, and WHR were more likely to be physically inactive, past smokers, use aspirin and acetaminophen, and have higher BMI at early adulthood, but less likely to be current smokers and use menopausal hormone. They were more frequently diagnosed with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes, and also tended to consume more red meat but less fiber, resulting in lower scores on the healthy eating index30.

Table 1.

Baseline age-adjusted characteristics according to body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio in Nurses' Health Study participants (2008)*

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | Waist circumference (quintiles) | Waist-to-hip ratio (quintiles) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| <25.0 | 25.0–30.0 | ≥30.0 | Q1 | Q3 | Q5 | Q1 | Q3 | Q5 | |

| Age, years† | 73.2(6.9) | 71.9(6.5) | 70.4(6.0) | 71.5(6.6) | 72.9(6.7) | 73.4(6.8) | 71.0(6.4) | 72.8(6.7) | 74.6(6.8) |

| White race, % | 97.4 | 97.4 | 97.0 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 98.1 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 97.7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.2(1.9) | 27.3(1.4) | 34.2(4.1) | 21.6(2.8) | 25.2(3.4) | 30.8(5.4) | 23.6(4.1) | 25.8(5.1) | 27.5(5.0) |

| Body mass index at age 18, kg/m2 | 20.4(2.3) | 21.3(2.6) | 22.7(3.4) | 20.4(2.1) | 20.8(2.4) | 22.2(3.3) | 21.0(2.5) | 21.0(2.8) | 21.3(2.8) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 79.5(9.6) | 90.2(10.4) | 101.8(12.6) | 70.3(3.7) | 85.1(1.7) | 106.7(8.3) | 73.5(7.5) | 86.1(9.3) | 101.0(11.1) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.8(0.1) | 0.8(0.1) | 0.9(0.1) | 0.7(0.1) | 0.8(0.1) | 0.9(0.1) | 0.7(0.0) | 0.8(0.0) | 0.9(0.0) |

| Alcohol, g/d | 7.8(11.8) | 6.0(10.6) | 3.7(8.2) | 7.8(11.1) | 6.9(11.0) | 4.5(9.7) | 6.8(10.0) | 6.7(11.0) | 5.8(11.7) |

| Vigorous activity, MET-h/week | 11.3(19.7) | 8.6(15.1) | 5.9(11.8) | 13.2(20.5) | 9.7(16.4) | 6.8(13.1) | 11.7(18.3) | 9.6(16.1) | 8.2(16.2) |

| Past smoker, % | 45.4 | 48.4 | 49.7 | 45.1 | 46.1 | 49.3 | 44 | 47.5 | 48.3 |

| Current smoker, % | 6.8 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

| Current postmenopausal hormone user, % | 16.7 | 13.2 | 9.4 | 18.3 | 16.4 | 10.7 | 17.6 | 14.7 | 12.5 |

| Past postmenopausal hormone user, % | 60.4 | 61.2 | 60.3 | 60.9 | 62.0 | 62.6 | 61.9 | 61.9 | 62.0 |

| Multivitamin use, % | 76.1 | 74.3 | 71.0 | 78.1 | 76.7 | 75.3 | 78.3 | 75.4 | 76.1 |

| Aspirin use, % | 51.4 | 54.9 | 55.5 | 51.7 | 55.7 | 58.0 | 53.3 | 56.5 | 59.0 |

| Other NSAID use, % | 21.3 | 24.0 | 22.9 | 21.1 | 23.7 | 22.3 | 22.6 | 23.2 | 21.8 |

| Acetaminophen use, % | 25.0 | 29.1 | 33.1 | 23.3 | 28.9 | 34.5 | 26.2 | 29.9 | 31.8 |

| History of hypertension, % | 40.3 | 52.6 | 63.7 | 36.3 | 49.2 | 62.1 | 38.8 | 50.0 | 57.5 |

| History of hypercholesterolemia, % | 41.9 | 51.6 | 54.6 | 38.1 | 51.0 | 55.5 | 38.8 | 49.0 | 55.8 |

| History of diabetes, % | 4.2 | 9.2 | 20.0 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 18.0 | 3.1 | 6.5 | 15.3 |

| Physical examination, % | 82.8 | 83.5 | 81.5 | 84.5 | 86.0 | 84.3 | 85.5 | 85.0 | 85.1 |

| Total energy intake, kcal/d | 1663(524) | 1661(532) | 1643(545) | 1667(524) | 1683(517) | 1687(541) | 1676(524) | 1699(526) | 1684(547) |

| Protein intake, g/d | 70.9(9.0) | 73.1(9.3) | 75.1(9.7) | 71.2(9.1) | 71.9(8.7) | 73.7(9.4) | 72.5(9.2) | 71.9(8.8) | 72.4(9.3) |

| Cholesterol intake, g/d | 221.5(55.8) | 233.6(52.7) | 248.2(59.3) | 216.6(53.8) | 226.6(51.4) | 240.9(55.0) | 224.0(54.2) | 226.8(53.1) | 231.9(53.8) |

| Fiber intake, g/d | 18.9(4.7) | 18.5(4.2) | 18.1(4.1) | 19.7(4.9) | 18.7(4.1) | 18.1(4.0) | 19.6(4.6) | 18.7(4.4) | 18.2(4.2) |

| Red meat intake, serving/d | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.5) | 0.9(0.5) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.5) | 1.0(0.5) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.5) | 0.9(0.5) |

| Alternate Healthy Eating Index score | 48.7(8.7) | 47.8(8.3) | 47.0(8.2) | 50.2(8.8) | 48.1(8.2) | 46.8(8.2) | 49.8(8.5) | 48.0(8.4) | 47.2(8.2) |

Body mass index was assessed in 2008; waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio were assessed in 2000. Values are means(SD) or percentages and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population.

Value is not adjusted for age.

Over 6 years encompassing 248,001 person-years of follow-up, we documented a total of 1,084 incident cases of diverticulitis. We found a linear association between BMI and increasing risk of diverticulitis (Table 2). After adjustment for various lifestyle and dietary risk factors, compared to women in the reference group with a BMI < 22.5 kg/m2, the HRs (95% CIs) were 1.31 (1.09–1.59), 1.35 (1.09–1.68), 1.51 (1.23–1.86), and 1.42 (1.08–1.85; P-trend < 0.001) for those with a BMI 25.0–27.4, 27.5–29.9, 30.0–34.9, and ≥ 35.0 kg/m2, respectively. The association of BMI with diverticulitis did not appear to differ according to subgroups defined by age, smoking status, or physical activity (Supplemental Table 1). Findings were similar in the sensitivity analysis using follow-up from 1990 to 2014, which included 5,377 incident diverticulitis cases during 1,391,633 person-years (Supplemental Table 2). Compared to women with a BMI < 22.5 kg/m2, those with a BMI 30.0–34.9 had a HR of 1.45 (95% CI, 1.32–1.60), and those with a BMI ≥ 35.0 kg/m2 had a HR of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.41–1.78; P-trend < 0.001). Higher BMI was also associated with increased risk of diverticular bleeding (Table 2). Compared to women with a BMI < 22.5 kg/m2, the HRs (95% CIs) were 1.98 (1.32–2.98), 1.97 (1.24–3.13), and 1.56 (1.01–2.41; P-trend = 0.02) for those with a BMI 25.0–27.4, 27.5–29.9, and ≥ 30.0 kg/m2, respectively.

Table 2.

Body mass index and risk of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding (2008–2014)*

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| <22.5 | 22.5–24.9 | 25.0–27.4 | 27.5–29.9 | 30.0–34.9 | ≥35.0 | P for trend | |

| Diverticulitis | |||||||

| No. of cases | 207 | 199 | 238 | 159 | 196 | 85 | |

| Person-years | 58787 | 52515 | 50683 | 32632 | 36288 | 17096 | |

| Age | 1 (ref) | 1.08 (0.89, 1.32) | 1.34 (1.11, 1.62) | 1.39 (1.13, 1.71) | 1.55 (1.27, 1.89) | 1.42 (1.10, 1.84) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate† | 1 (ref) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.31) | 1.32 (1.09, 1.59) | 1.36 (1.10, 1.69) | 1.52 (1.24, 1.87) | 1.43 (1.10, 1.87) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate+diet‡ | 1 (ref) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.30) | 1.31 (1.09, 1.59) | 1.35 (1.09, 1.68) | 1.51 (1.23, 1.86) | 1.42 (1.08, 1.85) | <0.001 |

| Diverticular bleeding§ | |||||||

| No. of cases | 61 | 55 | 73 | 41 | 61 | ||

| Person-years | 58278 | 51929 | 50061 | 32187 | 52600 | ||

| Age | 1 (ref) | 1.22 (0.82, 1.81) | 1.79 (1.22, 2.64) | 1.65 (1.07, 2.55) | 1.31 (0.88, 1.96) | 0.10 | |

| Multivariate† | 1 (ref) | 1.26 (0.84, 1.90) | 1.95 (1.30, 2.93) | 1.87 (1.18, 2.96) | 1.52 (0.99, 2.34) | 0.03 | |

| Multivariate+diet‡ | 1 (ref) | 1.30 (0.86, 1.95) | 1.98 (1.32, 2.98) | 1.97 (1.24, 3.13) | 1.56 (1.01, 2.41) | 0.02 | |

Body mass index was updated every 2 years from 2008 to 2012.

Adjusted for menopausal status and menopausal hormone use, vigorous activity, alcohol intake, smoking, aspirin use, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, multivitamin use, acetaminophen use, physical examination, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and calorie intake.

Further adjusted for dietary intake of fiber and red meat.

Categories of body mass index 30.0–34.9 and ≥35.0 were combined for diverticular bleeding because of limited case number in single categories.

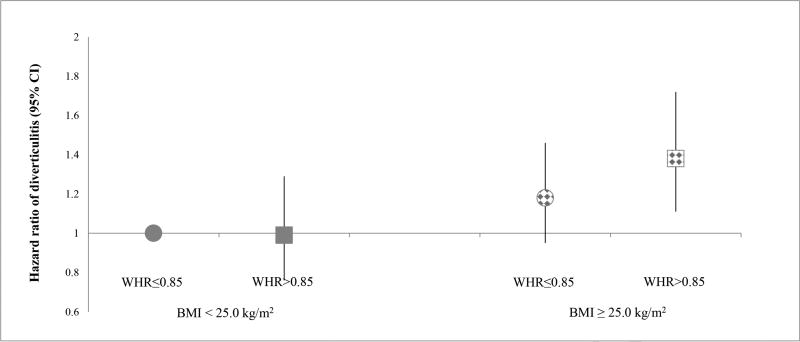

We also examined the association of WC and WHR as measures of central adiposity with risk of diverticulitis (Table 3). Compared to women in the lowest quintile, the multivariable HRs were 1.35 (95% CI, 1.02–1.78; P-trend = 0.06) among those in the highest quintile of WC and 1.40 (95% CI, 1.07–1.84; P-trend = 0.04) among those in the highest quintile of WHR. With additional adjustment for BMI, the associations for WC (multivariable HR, 1.16; 95% CI: 0.82–1.63; P-trend = 0.57) and WHR (multivariable HR, 1.31; 95% CI: 0.99–1.73; P-trend = 0.15) were attenuated and became not significant when comparing extreme quintiles. We further classified participants according to combined categories of BMI (< 25 vs. ≥ 25 kg/m2) and WHR (≤ 0.85 vs. > 0.85), with the group with BMI < 25 kg/m2 and WHR ≤ 0.85 as the reference (Figure 1). Women who had a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and WHR > 0.85 showed the highest risk of diverticulitis compared to the reference group (multivariable HR: 1.38; 95% CI, 1.11–1.72). Moreover, the association between WHR and diverticulitis appeared to be more evident among women who were overweight or obese. In the sensitivity analysis using follow-up from 1990 to 2014, WC and WHR were significantly associated with risk of diverticulitis even after adjusting for BMI (Supplemental Table 3). After accounting for BMI in addition to potential confounders, compared to women in the lowest quintile, the HRs among those in the highest quintile were 1.26 (95% CI, 1.10–1.44; P-trend < 0.001) for WC and 1.23 (95% CI, 1.10–1.37; P-trend < 0.001) for WHR.

Table 3.

Waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and risk of diverticulitis (2008–2014)*

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference (quintiles) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 99 | 132 | 89 | 148 | 129 | |

| Person-years | 29443 | 29226 | 26210 | 31483 | 28552 | |

| Age | 1 (ref) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.76) | 1.03 (0.77, 1.38) | 1.43 (1.11, 1.85) | 1.34 (1.03, 1.75) | 0.04 |

| Multivariate† | 1 (ref) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.76) | 1.03 (0.77, 1.37) | 1.42 (1.09, 1.85) | 1.35 (1.02, 1.79) | 0.05 |

| Multivariate+diet‡ | 1 (ref) | 1.35 (1.03, 1.76) | 1.02 (0.76, 1.37) | 1.42 (1.09, 1.85) | 1.35 (1.02, 1.78) | 0.06 |

| Multivariate+diet+BMI | 1 (ref) | 1.28 (0.98, 1.69) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.27) | 1.25 (0.92, 1.68) | 1.16 (0.82, 1.63) | 0.57 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (quintiles) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 98 | 127 | 116 | 116 | 134 | |

| Person-years | 28846 | 29196 | 28504 | 28777 | 28736 | |

| Age | 1 (ref) | 1.28 (0.99, 1.67) | 1.22 (0.93, 1.59) | 1.22 (0.93, 1.60) | 1.43 (1.10, 1.87) | 0.02 |

| Multivariate† | 1 (ref) | 1.27 (0.98, 1.66) | 1.21 (0.92, 1.58) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58) | 1.41 (1.08, 1.85) | 0.04 |

| Multivariate+diet‡ | 1 (ref) | 1.27 (0.97, 1.66) | 1.20 (0.92, 1.58) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.57) | 1.40 (1.07, 1.84) | 0.04 |

| Multivariate+diet+BMI | 1 (ref) | 1.24 (0.95, 1.61) | 1.16 (0.88, 1.53) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.49) | 1.31 (0.99, 1.73) | 0.15 |

Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio were assessed in 2000. For waist circumference, Q1: 50.8–74.9 cm; Q2: 75.6–81.3 cm; Q3: 81.9–88.3 cm; Q4: 88.9–96.5 cm; Q5: 97.2–168.9cm. For waist-to-hip ratio, Q1: 0.43–0.76; Q2: 0.76–0.80; Q3: 0.80–0.85; Q4: 0.85–0.90; Q5: 0.90–1.93.

Adjusted for height, menopausal status and menopausal hormone use, vigorous activity, alcohol intake, smoking, aspirin use, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, multivitamin use, acetaminophen use, physical examination, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and calorie intake.

Further adjusted for dietary intake of fiber and red meat.

Figure 1.

Risk of diverticulitis according to joint categories of body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio (2008–2014), with women who had a body mass index < 25 kg/m2 and waist-to-hip ratio ≤ 0.85 as the reference group. Body mass index was updated every 2 years from 2008 to 2012, and waist-to-hip ratio was assessed in 2000. Model was adjusted for age, menopausal status and menopausal hormone use, vigorous activity, alcohol intake, smoking, aspirin use, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, multivitamin use, acetaminophen use, physical examination, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, calorie intake, fiber intake, and red meat intake.

Table 4 shows the weight change from early adulthood at age 18 years to present age in relation to incident diverticulitis. In the analysis controlling for age, height, and weight at 18 years of age, women who gained 2.0–5.9 kg from age 18 years to the present had a 39% increased risk of diverticulitis (95% CI, 0%–96%), and women who gained 20 kg or more had an 80% increased risk (95% CI, 33%–144%; P-trend < 0.001), compared to those maintaining their weight with loss or gain no greater than 2.0 kg. The association was robust despite additional adjustment for potential confounders. A weight loss of 2.0 kg or more was not significantly associated with diverticulitis. The association of weight change from age 18 to current with diverticulitis did not appear to differ according to early adulthood BMI, age, smoking status, or physical activity (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 4.

Weight change from age 18 to current and risk of diverticulitis (2008–2014)*

| Weight change (kg) |

Median (kg) |

No. of cases |

Person- years |

Model 1† | Model 2‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss ≥2.0 | −5.9 | 56 | 21434 | 0.92 (0.62, 1.35) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.33) |

| Loss or gain <2.0 | 0 | 49 | 16852 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Gain 2.0–5.9 | 4.1 | 100 | 24800 | 1.39 (0.99, 1.96) | 1.39 (0.99, 1.95) |

| Gain 6.0–9.9 | 8.2 | 111 | 28922 | 1.32 (0.94, 1.85) | 1.30 (0.93, 1.82) |

| Gain 10.0–19.9 | 14.5 | 304 | 63511 | 1.66 (1.23, 2.25) | 1.62 (1.19, 2.19) |

| Gain ≥20.0 | 27.2 | 321 | 62664 | 1.80 (1.33, 2.44) | 1.73 (1.27, 2.36) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Weight change from age 18 to current was calculated by subtracting weight at age 18 from updated weight as reported in current questionnaire cycle.

Model 1 was adjusted for age, weight at age 18, and height.

Model 2 was further adjusted for menopausal status and menopausal hormone use, vigorous activity, alcohol intake, smoking, aspirin use, other NSAID use, multivitamin use, acetaminophen use, physical examination, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, calorie intake, fiber intake, and red meat intake.

In a secondary analysis, we assessed 4-year weight change during follow-up and risk of diverticulitis (Supplemental Table 5). Compared to women who maintained their weight (loss or gain < 1.0 kg), 4-year weight gain or weight loss was not significantly associated with risk of diverticulitis. The association was not significantly different between underweight/normal weight and overweight/obese people (Supplemental Table 6).

Among the 1,084 incident diverticulitis cases occurring during 2008 to 2014, we documented 240 incident recurrent cases with more than one episode. The association of BMI with an episode of recurrent diverticulitis seemed to be slightly stronger than that with non-recurrent diverticulitis cases (Supplemental Table 7). As compared to women with a BMI < 22.5 kg/m2, those with a BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 had a multivariable HR of 1.66 (95% CI, 1.09–2.51; P-trend = 0.002) for recurrent diverticulitis and 1.44 (95% CI, 1.16–1.79; P-trend < 0.001) for non-recurrent diverticulitis. We also utilized the full cohort with follow-up from 1992 to 2014 and identified 559 incident cases of surgery for diverticulitis. After adjusting for other risk factors, the HRs (95% CIs) were 1.71 (1.30–2.24), 1.65 (1.22–2.24), 1.67 (1.24–2.26), and 1.56 (1.06–2.30; P-trend = 0.002) for women with a BMI 25.0–27.4, 27.5–29.9, 30.0–34.9, and ≥ 35.0 kg/m2, respectively, as compared to those with a BMI < 22.5 kg/m2 (Supplemental Table 8).

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective cohort of women, we found a consistent association between BMI and risk of diverticulitis, independent of other dietary and lifestyle risk factors. Weight gain from early adulthood was also associated with increased risk. Our findings provide an additional rationale for maintaining a healthy weight throughout adulthood.

The relationship between BMI and diverticulitis was consistent with findings from previous studies4, 16–18. In a prior prospective study, Rosemar et al observed that a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 was associated with a 2–3 fold increase in the risk of hospitalization with a discharge diagnosis of diverticular disease among middle-aged men in Sweden17. However, data were not available on several potential confounders, including physical activity, diet, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. In several subsequent studies4, 18, the association between BMI and diverticular disease requiring hospitalization was shown to be independent of other risk factors. Moreover, BMI was strongly associated with risk for complicated diverticulitis18. However, because all of these studies have been based on registry-level data and included only hospitalized patients, their results may not be readily generalizable to the larger group of patients with less severe disease managed in the outpatient setting31. Our prior analysis among men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study showed an association of obesity with diverticulitis that included both less severe forms of the disease treated with antibiotics in the outpatient setting as well as more severe cases that led to hospitalization or surgery16. The current study extends those prior findings by offering evidence that obesity and weight change are associated with an increased risk of both mild and severe diverticulitis in women, and the associations did not differ according to age, smoking, physical activity, or body mass index at early adulthood.

Unlike the previous study where we demonstrated that the associations of WC and WHR with diverticulitis remained largely unchanged with further adjustment of BMI in men16, we showed these associations might not be independent of BMI in this cohort of women. Yet, when BMI and WHR were jointly assessed, WHR appeared to play a role in determining diverticulitis among women who were overweight or obese. Accumulating evidence indicates that WC and WHR are positively associated with risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer as well as mortality beyond overall adiposity32. Although WC and WHR indirectly measure total abdominal fat, they may be better markers of visceral fat than BMI. Visceral fat is metabolically more active than subcutaneous fat33 and has been suggested to promote systemic inflammation34, through which it may affect the pathogenesis of diverticulitis. Using a matched case-control study design, Yamada et al reported that compared to controls with diverticulosis, the proportion of visceral obesity defined by visceral fat area ≥ 100 cm2 in abdominal CT was significantly higher in the patients with left-sided-diverticulitis19. In another case series, diverticulitis patients with a higher visceral/subcutaneous fat ratio had an increased likelihood of requiring emergency surgery and having complications20. However, prospective, population-based data on abdominal adiposity and diverticulitis are lacking. Our data suggest that the clinical impact of slight increase in WC and WHR over time may be low in terms of risk of diverticulitis in women.

Excess adiposity tends to accrue during early and middle adulthood for most people. Based on data from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, the mean weight gain for U.S. women is approximately 0.5 to 1.0 kg per year35, 36, and this modest annual accumulation typically leads to obesity over time. In a recent analysis23, weight gain during adulthood has been associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cholelithiasis, and obesity-related cancers, as well as decreased odds of healthy aging, a composite measure of major chronic diseases and cognitive and physical function. Our results suggest that maintaining a healthy weight throughout adulthood may be important in the prevention of incident diverticulitis. In contrast, 4-year weight change during follow-up was not significantly associated with risk of diverticulitis, indicating that short-term weight change is not a risk factor for diverticulitis compared to current body weight or long-term weight change from early adulthood.

Our study has several strengths. First, we used a well-established cohort with prospective design and minimal loss of follow-up. Second, we had repeated anthropometric measurements, providing a unique opportunity to examine the long-term influence of adiposity and weight change on risk of diverticulitis. Finally, a comprehensive and longitudinal assessment of lifestyle and diet on repeated measurement enabled us to finely control for potential confounders.

Potential limitations of our study should be noted. First, anthropometric measurements were self-reported or recalled. However, robust validity has previously been established24, 25. Second, the ascertainment of diverticulitis was also based on recalled and self-reported information. Yet, we have restricted follow-up to prospective assessment of diverticulitis from 2008 to 2014 to reduce the potential of recall bias and selection bias. Although the validity of self-reported diverticulitis has been endorsed in the cohort with 88% of self-reported cases confirmed by a review of medical records, we acknowledge that the possibility of misclassification of some reported cases, which would attenuate the association towards the null, could not be excluded. Third, data on WC and WHR were only collected over several years, and changes over time would cause measurement error. However, random errors in exposure assessments generally attenuate true associations towards the null. Last, although the homogeneity of health care access and socioeconomic status of our population helps minimize confounding and enhances the internal validity, the results may not be as generalizable to other populations. Future investigations are needed to determine whether BMI and abdominal adiposity are associated with a similar risk of diverticulitis in a broader, more diverse population.

In conclusion, our results indicate an association between obesity and risk of diverticulitis in a prospective cohort study of women. Weight gain during adulthood was also associated with increased risk. Given the increasing prevalence of diverticulitis, with relatively few known modifiable risk factors, our findings have important clinical implications in the prevention of diverticulitis and provide further scientific rationale for adults to maintain a healthy weight throughout adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants UM1 CA186107, R01 DK101495 and K24 DK 098311 from the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: Study concept and design: WM, LLS, ATC; acquisition of data: KW, ELG, LLS, ATC; statistical analysis: WM; interpretation of data: all authors; drafting of the manuscript: WM, LLS, ATC; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, et al. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strate LL. Lifestyle factors and the course of diverticular disease. Dig Dis. 2012;30:35–45. doi: 10.1159/000335707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Allen NE, et al. Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. BMJ. 2011;343:d4131. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowe FL, Balkwill A, Cairns BJ, et al. Source of dietary fibre and diverticular disease incidence: a prospective study of UK women. Gut. 2014;63:1450–6. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Y, Strate LL, Keeley BR, et al. Meat intake and risk of diverticulitis among men. Gut. 2017 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strate LL, Keeley BR, Cao Y, et al. Western Dietary Pattern Increases, and Prudent Dietary Pattern Decreases, Risk of Incident Diverticulitis in a Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1023–1030. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, et al. Physical activity decreases diverticular complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1221–30. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humes DJ, Ludvigsson JF, Jarvholm B. Smoking and the Risk of Hospitalization for Symptomatic Diverticular Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study from Sweden. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:110–4. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Serag H. The association between obesity and GERD: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2307–12. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreras-Torres R, Johansson M, Gaborieau V, et al. The Role of Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, and Metabolic Factors in Pancreatic Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez J, Sanchez-Paya J, Palazon JM, et al. Is obesity a risk factor in acute pancreatitis? A meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2004;4:42–8. doi: 10.1159/000077025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:556–65. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Giovannucci EL. Sex differences in the association of obesity and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, et al. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1486–93. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, et al. Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:115–122. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosemar A, Angeras U, Rosengren A. Body mass index and diverticular disease: a 28-year follow-up study in men. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:450–5. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hjern F, Wolk A, Hakansson N. Obesity, physical inactivity, and colonic diverticular disease requiring hospitalization in women: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:296–302. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada E, Ohkubo H, Higurashi T, et al. Visceral obesity as a risk factor for left-sided diverticulitis in Japan: a multicenter retrospective study. Gut Liver. 2013;7:532–8. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.5.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Docimo S, Jr, Lee Y, Chatani P, et al. Visceral to subcutaneous fat ratio predicts acuity of diverticulitis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2808–2812. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE. The Nurses' Health Study: 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health. 1997;6:49–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song M, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, et al. Adulthood Weight Change and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the Nurses' Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:620–7. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Y, Manson JE, Yuan C, et al. Associations of Weight Gain From Early to Middle Adulthood With Major Health Outcomes Later in Life. JAMA. 2017;318:255–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990;1:466–73. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, et al. The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:991–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:894–900. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1114–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. discussion 1127-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobias DK, Pan A, Jackson CL, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among adults with incident type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:233–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK, et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:163–73. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schechter S, Mulvey J, Eisenstat TE. Management of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis: results of a survey. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:470–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02234169. discussion 475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C, Rexrode KM, van Dam RM, et al. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Circulation. 2008;117:1658–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Einstein FH, Atzmon G, Yang XM, et al. Differential responses of visceral and subcutaneous fat depots to nutrients. Diabetes. 2005;54:672–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, et al. Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960–2002. Adv Data. 2004:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katan MB, Ludwig DS. Extra calories cause weight gain--but how much? JAMA. 2010;303:65–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.