Abstract

Previous research suggests that women who experience pain during intercourse also experience higher rates of depressive symptoms. Loneliness might be one factor that contributes to this relationship. We hypothesized that women who experience more severe and interfering pain during intercourse would report higher rates of loneliness and higher rates of depressive symptoms. Further, we hypothesized that loneliness would mediate the relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. A total of 104 female participants (85.6% white, 74.03% partnered, 20.9 [3.01] years old) completed an online survey including demographic information, PROMIS Vaginal Discomfort Measure, PROMIS Depression Measure, and Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale. Pearson correlations and bootstrapped mediation analysis examined the relationships among pain during intercourse, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. Pain during intercourse, loneliness, and depressive symptoms were all significantly correlated (p < .05). Results of the mediation analysis indicated that loneliness was a significant mediator of the relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms (indirect effect = 0.077; 95% CI 0.05–0.19). After accounting for loneliness, pain during intercourse was not significantly related to depressive symptoms, suggesting that loneliness fully mediated the relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with previous studies highlighting that pain during intercourse is related to depressive symptoms. The current study adds to that literature and suggests that more frequent and severe pain during intercourse leads to more loneliness, which then leads to increased depressive symptoms. This line of work has important implications for treating women who experience depressive symptoms and pain during intercourse.

Keywords: Loneliness, Sexual function, Depression, Vaginismus, Dyspareunia, Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder

Introduction

Sexual intercourse plays an important role in romantic relationships and has implications for mental and physical health. Individuals who engage in sexual intercourse more frequently are happier and more satisfied emotionally, physically, and with life in general (Brody & Costa, 2009; Cheng & Smyth, 2015). Sexual satisfaction is also linked to improved quality of romantic relationships (Sprecher, 2002). Similarly, individuals who are unsatisfied with their sex lives also report dissatisfaction within their relationships (Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Smith et al., 2011; Spence, 1997).

Sexual dysfunction, or difficulty engaging in sexual activity, affects 14–53% of women, with approximately 40–50% of women endorsing at least one sexual symptom over their lifetime (Basson et al., 2004; Heiman, 2002; Nappi et al., 2016). Sexual dysfunction is associated with poorer quality and lower frequency of sexual intercourse, which can lead to decreased physical pleasure during sexual intercourse and increased negative mood (Stephenson & Meston, 2012). Further, sexual dysfunction is related to more psychological distress and less life and relationship satisfaction (Cano, Johansen, Leonard, & Hanawalt, 2005; Smith & Pukall, 2011). Some chronic health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and chronic pain are associated with sexual dysfunction due to the conditions themselves as well as the side effects of pharmacological treatments for those conditions (Burchardt et al., 2002; Cano et al., 2005).

Pain can be a defining characteristic of sexual disorders. Dyspareunia, or pain during intercourse, affects between 12 and 44% of women (Danielsson, Sjöberg, Stenlund, & Wikman, 2003; Jamieson & Steege, 1996; Landry & Bergeron, 2009). Vulvodynia is the one of the most common causes of pain during intercourse and affects 7–8% of women (Pukall et al., 2016). The DSM-5 diagnosis Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder is described as persistent or recurrent difficulties with one or more of the following for at least 6 months that results in significant distress: (1) vaginal penetration during intercourse; (2) marked vulvovaginal or pelvic pain during vaginal intercourse or penetration attempts; (3) marked fear or anxiety about vulvovaginal or pelvic pain in anticipation of, during, or as a result of vaginal penetration; and (4) marked tensing or tightening of the pelvic floor muscles during attempted vaginal penetration (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This diagnosis is a merging of the previous DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of Dyspareunia and Vaginismus. Despite increasing recognition of the importance of addressing pain during intercourse and the associated disorders, up to 40% of women with such difficulties never seek treatment, and up to 48% never receive a formal diagnosis (Harlow et al., 2014). Thus, there is a large population of women who do not carry a formal diagnosis but who nonetheless experience clinically significant symptoms of pain during intercourse—research is needed to better characterize their psychosocial experience and identify areas of unmet clinical needs. To this end, the present study examined pain during intercourse in a non-clinical, young adult population.

Women who experience pain during sexual intercourse, regardless of whether they have been diagnosed with a sexual disorder, are more likely to suffer from general psychological distress and increased depressive symptoms in particular (Boerner & Rosen, 2015; Khandker et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2013; Schnatz, Whitehurst, & O’Sullivan, 2010). In a study of 63 women with chronic pelvic pain, increased pelvic pain and decreased sexual function were significantly related to increased depressive symptoms, which in turn was related to decreased support, defined by relationship quality with their partners (Randolph & Reddy, 2006). A large retrospective analysis of clinical data from the Netherlands found that women with genital pain, painful intercourse, and/or other vaginal/vulvar complaints were over twice as likely to experience clinically significant depressive symptoms (Leusink, Kaptheijns, Laan, van Boven, & Lagro-Janssen, 2016). Similarly, Khandker et al. (2011) found that a DSM-IV diagnosed depressive disorder was an independent risk factor for subsequent vulvodynia, and vulvodynia increases the risk of new and recurrent onset of a mood disorder, highlighting the bidirectional temporal relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. Although the relationship between painful sexual intercourse and depressive symptoms is well-documented, the factors that are driving this relationship and the temporal associations among these factors have yet to be elucidated. Previous research suggests that loneliness is one factor that may be important in this context.

Loneliness has important psychological and physical health implications. For example, longitudinal studies show that loneliness predicted changes in depressive symptoms in a variety of populations such as children, patients with cancer and HIV, adolescents, college freshmen, the elderly, and healthy adults (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010; Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006a; Grov, Golub, Parsons, Brennan, & Karpiak, 2010; Heikkinen & Kauppinene, 2004; Jaremka et al., 2013, 2014; Qualter, Brown, Munn, & Rotenberg, 2010; Reyes-Gibby, Aday, Anderson, Mendoza, & Cleeland, 2006; Segrin, 1999; Vanhalst et al., 2012; Wei, Russell & Zakalik, 2005). People who are lonelier also tend to engage in less physical activity and have higher rates of sleep disturbance, both of which are related to increased pain and depressive symptoms (Cheatle et al., 2016; Emery, Wilson, & Kowal, 2014; Harrison, Wilson, Heron, Stannard, & Munafò, 2016; Hawkley, Thisted, & Cacioppo, 2009; Jaremka et al., 2013, 2014; Landmark, Romundstad, Borchgrevink, Kaasa, & Dale, 2011).

Although women who experience pain during intercourse are more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms, less is known about the relationship between pain during intercourse and loneliness. In a qualitative study of couples dealing with vulvar pain, women commonly reported feeling socially isolated and less connected (Connor, Robinson, & Wieling, 2008). In a similar study by Svedhem, Eckert, and Wijma (2013), loneliness was a major theme to emerge from the interviews, in which women with vaginismus reported they had no one to talk to, felt excluded, and felt forced to lie about their condition. Furthermore, in a survey of 1847 women who sought information from the National Vulvodynia Association, approximately 42% reported feelings of isolation, invalidation, or both (Nguyen, Ecklund, MacLehose, Veasley, & Harlow, 2012). These feelings may arise because women find it difficult to talk about their experiences with painful intercourse with friends, romantic partners, and even physicians (Brauer, Lakeman, Lunsen, & Laan, 2014; Elmerstig, Wijma, & Swahnber, 2013; Kingsberg, 2004).

Social isolation and loneliness are considered separate constructs. However, in a study relevant to the current one, Connor et al. (2008) used the terms interchangeably and employed a definition for social isolation that closely resembles that of loneliness. Whereas social isolation is an objective indicator of a lack of social connectedness, loneliness is a subjective experience—it is the dissonance between an individual’s perceived vs. preferred state of social connectedness (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Although one might expect social isolation to be closely related to loneliness, having fewer social connections does not necessarily imply that one is more lonely (Cacioppo et al., 2015a; Cacioppo, Grippo, London, Goossens, & Cacioppo, 2015b). The current study will adopt the most widely accepted definition of loneliness—a perceived lack of social connectedness that occurs when people feel their social needs are not being met (Cacioppo et al., 2006b).

In summary, women who experience pain during intercourse are more likely to experience depressive symptoms and may also be at increased risk for loneliness. However, the relationships among painful intercourse, depressive symptoms, and loneliness have not been specified. The current study aimed to clarify these relationships. We hypothesized that (1) women who experienced more severe and interfering pain during sexual intercourse would report higher levels of depressive symptoms and (2) loneliness would mediate the relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms such that individuals reporting higher levels of pain during intercourse would also report more loneliness and, as a result, more depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

Potential participants (n =148) completed an online anonymous screener that was described as being for women only. Only women who reported having engaged in sexual intercourse in the last 30 days were eligible to complete the survey. Therefore, women who had never had intercourse (n =19) or had not had intercourse in the past 30 days (n =25) were excluded from participating and did not complete the survey. No men attempted to complete the survey.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the University’s institutional review board. Potential participants were recruited from an Introduction to Psychology course at an urban, Midwestern university. Students interested in participating in the study signed up via the psychology department research website. After providing informed consent, eligible participants (n =104) then completed the online anonymous survey including the measures listed below, as well as a demographic questionnaire. Measures were presented in random order to prevent order effects. Upon completion of the survey, participants were debriefed and received research credits toward their course requirements.

Measures

Demographic Information

Participants were asked demographic questions, including age, race and ethnicity, relationship status, sexual orientation, whether they had experienced sexual trauma in their lifetime, and whether a doctor had diagnosed them with a disorder associated with pain during intercourse. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 104)

| Mean (SD), n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20.9 (3.01) |

| Race/ethnicity | 89 (85.6%) White |

| 6 (5.8%) Black | |

| 4 (3.8%) Latino/Hispanic | |

| 4 (3.8%) Multi-racial | |

| 1 (1%) Choose not to answer | |

| Relationship status | 77 (74.03%) partnered |

| Sexual orientation | 98 (94.2%) heterosexual |

| Endorsed trauma | 14 (13.5%) |

| Endorsed pain diagnosis | 3 (2.9%) |

Depressive Symptoms

The PROMIS Short Form v1.0—Emotional Distress—Depression 6a (2015a) is a 6-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. Participants rated (0 =never to 5 =always) the frequency with which they experienced the following depressive symptoms in the past 7 days: worthlessness, helplessness, depression, hopelessness, feeling like a failure, and unhappiness. The responses were summed for a total score with a possible range of 0–30 (https://assessmentcenter.net/Manuals.aspx). None of the items were related to social connectedness, loneliness, or social isolation. The PROMIS Depression Scale has shown good convergent validity through its significant correlations, across multiple time points, with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (correlations ranged from .72 to .84; Pilkonis et al., 2014). Further, it demonstrated good reliability (alpha = 0.94) in the current study.

Pain During Intercourse

The 10-item Vaginal Discomfort scale from the PROMIS Item Bank v2.0 (2015b) was used to measure severity, frequency, and interference of vaginal pain during penetrative sexual intercourse. Participants rated their level of vaginal comfort (1 =very comfortable to 4 =very uncomfortable) and discomfort (1 =very low or none at all to 5 =very high); the frequency at which they experience discomfort during and after vaginal penetration (1 = almost never or never to 5 =almost always or always); the frequency at which they experience difficulties with sexual activity due to pain/discomfort and tightness (1 = never to 5 = always); the frequency at which they have to stop sexual activity due to pain/discomfort, tightness, or irritation/bleeding not caused by menstruation (1 =never to 5 =always); and the frequency at which they experience irritation/bleeding not caused by menstruation after sexual activity (1 =never to 5 =always). The responses were summed for a total score with a possible range of 10–49 (https://assessmentcenter.net/Manuals.aspx). The Vaginal Discomfort scale has been shown to have good convergent validity with the Pain subscale of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI; r = − .85) (Weinfurt et al., 2015) and demonstrated good reliability (alpha =0.88) in the current study.

Loneliness

The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale is a 20-item self-report measure of loneliness (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980). Participants rated the frequency at which they experience feelings of loneliness and social connectedness (1 = never to 4 =often). After reverse scoring nine of the items, responses were summed for a total score with a possible range of 20–80, where higher scores indicate more loneliness. Scores are commonly characterized as low (20–34), moderate (35–49), moderately high (50–64), and high (65–80) degree of loneliness. The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale has demonstrated good concurrent and discriminant validity in previous studies, such that loneliness scores were significantly correlated with scores on validated measures of depression and anxiety, as well as self-reported feelings of being abandoned, empty, hopeless, and isolated, but were not significantly correlated with conceptually unrelated feelings such as creativity, embarrassment, and surprise (Russell et al., 1980). The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale demonstrated good reliability (alpha = 0.93) in the current study.

Data Analysis

The data contained very few missing items; therefore, missing items were replaced with the mean of the completed items within the particular scale or measure. Pearson’s correlations were used to evaluate the bivariate associations among pain, depressive symptoms, and loneliness. A mediation analysis was conducted to test the hypothesis that loneliness would mediate the association between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. This analysis was conducted using Preacher and Hayes’s (2008) bootstrapping procedures and SPSS (version 22; IBM Corp. Released (2013), Armonk, NY) Process macro. Path a denotes the effect of pain during intercourse on loneliness, whereas path b is the effect of loneliness on depressive symptoms controlling for pain. This test of mediation was based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples to produce the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the mediator and was used to test the significance of both total and indirect effects. The mediation model was considered significant if zero was not contained within the 95% CI.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant demographics are presented in Table 1. On average, participants reported low levels of pain during intercourse (M =17.44, SD =6.35, T-score = 47.74), mild levels of depressive symptoms (M = 11.89, SD = 5 .24, T-score =54.7), and low-to-moderate levels of loneliness (M = 34.84, SD = 10.74).

Bivariate Associations Between Pain During Intercourse and Psychological Measures

All variables were significantly correlated. Pain during intercourse was positively correlated with loneliness (r =.22; df = 102; p < .05) and depressive symptoms (r = .25; df = 102; p < .05), meaning more frequent and severe pain during intercourse was related to higher levels of loneliness and depressive symptoms. Additionally, loneliness and depressive symptoms were positively correlated (r = .46; df =102; p< .01), meaning the higher levels of loneliness were related to higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Mediation

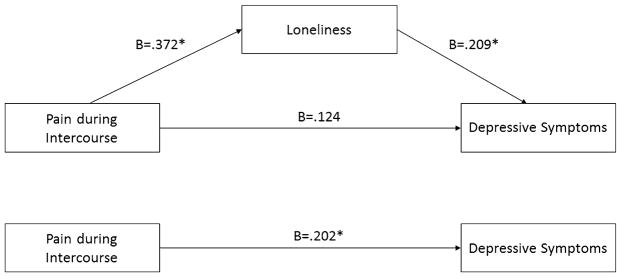

The potential mediating role of loneliness in the relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms was examined using a bias-corrected bootstrapped multiple mediation analysis with 10,000 bootstrapped resamples (Fig. 1). Results of the mediation analysis (Table 2) indicated that loneliness accounted for 23% of the variance in depressive symptoms. More severe pain during intercourse was associated with greater loneliness (a =.372), and greater loneliness was associated with greater depressive symptoms (b = .209). Pain during intercourse was indirectly related to greater depressive symptoms through loneliness (indirect effect =0.077; 95% CI 0.005–0.191). After accounting for loneliness, the relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms was no longer significant (direct effect =0.124; 95% CI −0.022 to 0.270), suggesting that the association of pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms was fully mediated by loneliness.

Fig. 1.

Model depicting relationship between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms through loneliness. B is the unstandardized regression coefficient. *p < .01

Table 2.

Bootstrapped multiple mediation analysis testing indirect effects of pain during intercourse on depressive symptoms through loneliness (n = 104)

| Effects | Point estimate | Bootstrapping BC 95% CI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Total | 0.202 | 0.045 | 0.359 |

| Loneliness | 0.077 | 0.051 | 0.191 |

Discussion

Women who experience pain during intercourse tend to report higher rates of depressive symptoms (Brotto, Basson, & Gehring, 2003; Meana, Binik, Khalifé, & Cohen, 1997; Nylanderlundqvist & Bergdahl, 2003; Randolph & Reddy, 2006; Schnatz et al., 2010; Walker & Keaton, 1992); however, the underlying drivers of this relationship have not been clarified. We examined loneliness as a potential mediator between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. The results of the current study indicated that women who experienced more severe and frequent pain during intercourse reported increased loneliness and depressive symptoms and that loneliness mediated the relationship between increased pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms.

Women who experience pain during intercourse might feel lonelier because of a perceived lack of support from the people around them, including their partners, close friends, and care teams. The Communal Coping Model of pain (Sullivan et al., 2001) highlights the importance of communicating pain-related distress to others in order to receive support and care. Women who are struggling to communicate their pain to important people in their lives may not be receiving adequate support and, thus, may experience increased feelings of loneliness. In a study of 591 women who reported pain during intercourse, Elmerstig et al. (2013) found that approximately 47% continued with intercourse despite pain, 22% feigned enjoyment of intercourse, and 33% did not tell their partner about their pain. These findings suggest that it is relatively common for women to hide their pain during intercourse from partners. A qualitative study suggests that young women might conceal their pain during intercourse from partners because they want to feel “normal” and/or fulfill their role as the “ideal woman” who is willing to have sex and who perceives and satisfies their partner’s sexual needs (Elmerstig, Wijma, & Berterö, 2008). Similarly, Svedhem et al. (2013) identified failure (as a sex partner, as a girlfriend, and as a person) and fear (of being abandoned, of pain, of the future, and of being cured) as common relationship-related responses in women with genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder. When it came to persisting through pain, women in the qualitative study by Elmerstig reported feelings of resignation, sacrifice, and guilt (Elmerstig et al., 2008). Women may also have trouble discussing pain during intercourse with partners, because they fear their partners’ reactions. Brauer et al. (2014) examined women’s motivations to continue with intercourse despite pain and found that women with vaginismus and dyspareunia exhibited fear avoidance, task persistence, and mate guarding motivations. In short, women continued to have intercourse despite pain due to their fear of or in order to avoid their partner’s reactions to their pain, and/or to protect their partner from their pain. Thirty-six percent of women in this study consistently persisted through the pain, and another 5% reported that they tolerated the pain some of the time.

Women who experience pain during intercourse may also feel uncomfortable talking to their close friends about their difficulties with intercourse. Svedhem et al. (2013) identified loneliness as a major theme in qualitative interviews. Loneliness included (1) feeling that there is no one to talk to or that no one would understand, (2) feeling excluded from friends’ jokes or stories about intercourse, and (3) feeling forced to lie to friends about their experiences with sexual intercourse. These findings highlight that the lack of communication about pain during intercourse extends beyond intimate partners to friends and social acquaintances, which may contribute to and/or exacerbate unmet social support needs, resulting in feelings of loneliness.

In addition to difficulties talking with partners and close friends, there is also a lack of trust and comfort related to discussing sexual intercourse and sexual dysfunction with physicians (Dolgun et al., 2014). In fact, women tend not to bring up sexual issues unless providers specifically ask about them (Kingsberg, 2004). Adegunloye and Ezeoke (2011) found that a majority of patients do not seek medical help for their sexual dysfunction, with 26% citing fear of stigma as the reason. This stigma might increase loneliness in people with sexual dysfunction. Indeed, loneliness is not only highly prevalent in a number of stigmatized populations such as those with mental illness and who are HIV-positive, but it has been shown to be a contributing factor for depressive symptoms in these populations (Grov et al., 2010; Laryea & Gien, 1993; Lindgren, Sundbaum, Eriksson, & Graneheim, 2014; Œwitaj, Grygiel, Anczewska, & Wciorka, 2014). Further investigation is needed to understand the stigma experienced by people with sexual dysfunction and how this impacts loneliness. In summary, if women are not comfortable sharing their pain experiences with others, especially partners, close friends, and physicians, they may not receive adequate social or emotional support (Sullivan et al., 2001), which may engender feelings of loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2006b).

There are several potential clinical implications of the current findings. Comorbid depressive symptoms are a leading cause of increased disease burden in a variety of health populations (Göthe et al., 2012; Moussavi et al., 2007; Noyes & Kathol, 1985). Depressive symptoms, particularly those that are subclinical, are also prevalent among women who experience pain during intercourse (Khandker et. al., 2011); as such, some of these women may benefit from treatment for depressive symptoms even if these symptoms fall below diagnostic thresholds. Indeed, such treatment has been shown to improve health outcomes, such as quality of life, functional ability, and medication adherence across a range of health populations including people with chronic pain, cancer patients and survivors, and stroke survivors (Ho et al., 2014; Markowitz, Gonzalez, Wilkinson, & Safren, 2011; Osborn, Demoncada, & Feuerstein, 2006; Pence, O’Donnell, & Gaynes, 2012; Yohannes & Alexopoulos, 2014).

Results from the current study also suggest that loneliness is a potential treatment target for women who experience pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. Interventions addressing maladaptive social cognitions—e.g., I can’t tell people about my difficulties with sex. They’ll think I’m damaged. Men won’t want to date me if I can’t have sex.—may be particularly effective, along with other strategies that address social skills and increase social support and opportunities for rewarding social contact (Cacioppo et al., 2015b; Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), delivered in-person and online, is a promising intervention and has been shown to decrease loneliness in healthy young adults (McWhirter & Horan, 1996; Tatlilioğlu, 2013). Additionally, it may be helpful to reduce the stigma associated with pain during intercourse. Evidence-based treatments for reducing internalized or perceived stigma are currently lacking (Griffiths, Carron-Arthur, Parsons, & Reid, 2014). Nevertheless, Heijnders and Van Der Meij (2006) argued that two things are necessary to reduced stigma—increased public knowledge about stigmatized disorders and diseases, and increased patient involvement in developing interventions to reduce perceived stigma—both of which seem relevant to the stigma associated with pain during intercourse.

Partnered women might also benefit from dyadic therapies or couples counseling. For example, three meta-analyses of couples-oriented interventions in patients with chronic illness demonstrated that psychosocial symptoms, including depressive symptoms and pain, were significantly reduced overall, when compared with both usual care and patient-only interventions (Martire, 2005; Martire, Lustig, Schulz, Miller, & Helgeson, 2004; Martire, Schulz, Helgeson, Small, & Saghafi, 2010). One particularly interesting and relevant finding was reported by Manne, Ostroff, Winkel, Grana, and Fox (2005) in breast cancer patients—a couples-oriented intervention was most helpful in dyads where the patient perceived their spouse as unsupportive. This finding suggests that couples-oriented psychosocial interventions might help women who conceal their intercourse-related pain from partners. Given the theoretical and research evidence that intimacy (Bois, Bergeron, Rosen, McDuff, & Grégiore, 2013; Ferriera, Narciso, & Novo, 2012; Witherow et al., 2017) and interpersonal connectedness (Muise, Bergeron, Impett, & Rosen, 2017; Rosen, Rancourt, Corsini-Munt, & Bergeron, 2014) are important determinants of women’s self-efficacy regarding pain during intercourse, interventions might seek to enhance these factors within the relationship (Dandenneau & Johnson, 1994). For example, cognitive behavioral interventions targeting self-disclosure, empathy, and communication have shown to be effective in promoting marital intimacy (Kardan-Souraki, Hamzehgardeshi, Asadpour, Mohammadpour, & Khani, 2016).

Efforts to reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms may also help ease some of the pain experienced during intercourse. According to the circular cognitive behavioral model of provoked vestibulodynia, cognitive-emotional processes such as catastrophizing and fear of pain can lead to physical reactions such as pelvic floor tension and decreased lubrication that ultimately lead to more pain (ter Kuile, Both, & van Lankveld, 2010). Interventions such as CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based stress reduction that target these psychosocial processes might help to alleviate some of the bodily reactions that cause or maintain pain during intercourse (Dunkley & Brotto, 2016; McCracken & Vowles, 2014; Rosenbaum, 2013; ter Kuile et al., 2010).

Increased treatment accessibility is paramount for those experiencing pain during intercourse, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. Berman et al. (2003) found that 40% of sampled women did not seek treatment for their sexual issues, with 54% of those women reporting that they wanted to. Furthermore, providers are not routinely assessing for sexual dysfunction. Although 90% of sampled physicians endorsed the belief that sexual issues should be discussed and addressed, 94% reported that they were unlikely to discuss these issues with patients (Haboubi & Lincoln, 2003). Only 40% of OB/GYNs regularly ask patients about sexual problems (Sobecki, Curlin, Rasinski, & Lindau, 2012), and only 57% of physicians overall report feeling comfortable engaging in conversations with patients about sexual issues (Haboubi & Lincoln, 2003). This reluctance may be due to insufficient training. In a survey of over 2000 medical students, more than half reported feeling that they had not received adequate training on sexuality (Shindel et al., 2010). Medical training in sexuality generally focuses on preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, while coverage of sexual function and dysfunction is rare or nonexistent (Shindel & Parish, 2013). Enhanced medical education in human sexuality, particularly focused on building skills to effectively manage discussions about sexual health with patients, could lead to increased treatment seeking behavior in women with sexual dysfunction. Indeed, of physicians who had received training in sexual issues, 53% reported an improvement in their knowledge and practice (Haboubi & Lincoln, 2003).

Several study limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we could not confirm the temporal relationships among pain during intercourse, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. Longitudinal or experimental designs would further elucidate the directionality of these relationships. Second, because the sample consisted of mostly college-aged, White, heterosexual women who were currently partnered, the results may not generalize to all women who experience pain during intercourse. Thus research with larger, more diverse samples of women, including those who are not in a committed relationship, would facilitate better understanding of the important cross-cultural similarities and differences of the relationships examined herein. Relatedly, relational distress and comorbid pain conditions were not included in the current analyses; thus, future studies are needed to determine whether and how these factors are associated with sexual functioning, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among partnered and non-partnered women. Third, given the relatively low average scores on measures of pain and depressive symptoms, the results of this study may not generalize to a clinical population. Future studies should examine these relationships in clinical samples or samples of women who report severe, frequent pain, and in women who are not currently sexually active, as pain during intercourse might prevent women from engaging in sexual intercourse.

This study provides new insights into a possible mechanism underlying the association between pain during intercourse and depressive symptoms. The results suggest that women who experience pain during intercourse report higher rates of depressive symptoms, which is largely due to their increased loneliness. Future studies confirming these relationships would indicate a need for treatments that specifically address loneliness in order to improve the quality of life for women who experience pain during intercourse.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest All authors have read and approved the manuscript. All co-authors have contributed substantially to data analysis and manuscript preparation. Results from this study were presented at the 2016 IUPUI Spring Capstone Poster Session. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Adegunloye OA, Ezeoke GG. Sexual dysfunction—A silent hurt: Issues on treatment awareness. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8(5):1322–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K, … Schultz WW. Revised definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2004;1(1):40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, Pollets D, Chhabra S, Miles M, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: What gynecologists need to know about the female patient’s experience. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;79(3):572–576. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04695-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner KE, Rosen NO. Acceptance of vulvovaginal pain in women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: Associations with pain, psychological, and sexual adjustment. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2015;12(6):1450–1462. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois K, Bergeron S, Rosen NO, McDuff P, Grégoire C. Sexual and relationship intimacy among women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: Associations with sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and pain self-efficacy. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10:2024–2035. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer M, Lakeman M, Lunsen R, Laan E. Predictors of task-persistent and fear-avoiding behaviors in women with sexual pain disorders. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2014;11(12):3051–3063. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody S, Costa RM. Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile-vaginal intercourse, but inversely with other sexual behavior frequencies. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(7):1947–1954. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto LA, Basson R, Gehring D. Psychological profiles among women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: A chart review. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;24(3):195–203. doi: 10.3109/01674820309039673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt M, Burchardt T, Anastasiadis AG, Kiss AJ, Baer L, Pawar RV, … Shabsigh R. Sexual dysfunction is common and overlooked in female patients with hypertension. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2002;28(1):17–26. doi: 10.1080/009262302317250981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzer B, Campbell L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships. 2008;15(1):141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Cole SW, Capitanio JP, Goossens L, Boomsma DI. Loneliness across phylogeny and a call for comparative studies and animal models. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015a;10(2):202–212. doi: 10.1177/1745691614564876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015b;10(2):238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, Burleson M, Berntson GG, Nouriani B, et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006a;40(6):1054–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(2):453. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging. 2006b;21(1):140. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Johansen AB, Leonard MT, Hanawalt JD. What are the marital problems of chronic pain patients. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2005;9:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11916-005-0045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatle MD, Foster S, Pinkett A, Lesneski M, Qu D, Dhingra L. Assessing and managing sleep disturbance in patients with chronic pain. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2016;34(2):379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Smyth R. Sex and happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2015;112:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Connor JJ, Robinson B, Wieling E. Vulvar pain: A phenomenological study of couples in search of effective diagnosis and treatment. Family Process. 2008;47(2):139–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandeneau ML, Johnson SM. Facilitating intimacy: Interventions and effects. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1994;20(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson I, Sjöberg I, Stenlund H, Wikman M. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: Results from a population study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2003;31(2):113–118. doi: 10.1080/14034940210134040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolgun A, Asma S, Yildiz M, Aydin ÖS, Yildiz F, Düldül M, et al. Barriers to talking about sexual health issues with physicians. Journal of MacroTrend in Health and Medicine. 2014;2(1):264–268. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley CR, Brotto LA. Psychological treatments for provoked vestibulodynia: Integration of mindfulness-based and cognitive behavioral therapies. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2016;72(7):637–650. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmerstig E, Wijma B, Berterö C. Why do young women continue to have sexual intercourse despite pain? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(4):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmerstig E, Wijma B, Swahnberg K. Prioritizing the partner’s enjoyment: A population-based study on young Swedish women with experience of pain during vaginal intercourse. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;34(2):82–89. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2013.793665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery PC, Wilson KG, Kowal J. Major depressive disorder and sleep disturbance in patients with chronic pain. Pain Research & Management. 2014;19(1):35–41. doi: 10.1155/2014/480859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriera LC, Narciso I, Novo RF. Intimacy, sexual desire and differentiation in couplehood: A theoretical and methodological review. Journal of Marital Therapy. 2012;38:263–280. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.606885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göthe F, Enache D, Wahlund LO, Winblad B, Crisby M, Lökk J, et al. Cerebrovascular diseases and depression: Epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Panminerva Medica. 2012;54(3):161–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths KM, Carron-Arthur B, Parsons A, Reid R. Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):161–175. doi: 10.1002/wps.20129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010;22(5):630–639. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haboubi NHJ, Lincoln N. Views of health professionals on discussing sexual issues with patients. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2003;25(6):291–296. doi: 10.1080/0963828021000031188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, Kunitz CG, Nguyen RH, Rydell SA, Turner RM, MacLehose RF. Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: Populations-based estimates from 2 geographic regions. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;210(1):40–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L, Wilson S, Heron J, Stannard C, Munafò MR. Exploring the associations shared by mood, pain-related attention and pain outcomes related to sleep disturbance in a chronic pain sample. Psychology & Health. 2016;31(5):1–13. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2015.1124106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology. 2009;28(3):354–363. doi: 10.1037/a0014400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnders M, Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2006;11(3):353–363. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen RL, Kauppinen M. Depressive symptoms in late life: A 10-year follow-up. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2004;38(3):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman JR. Sexual dysfunction: Overview of prevalence, etiological factors, and treatments. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):73–78. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CS, Feng L, Fam J, Mahendran R, Kua EH, Ng TP. Coexisting medical comorbidity and depression: Multiplicative effects on health outcomes in older adults. International Psychogeriatrics. 2014;26(07):1221–1229. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. Released. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson DJ, Steege JF. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;87(1):55–58. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremka LM, Andridge RR, Fagundes CP, Alfano CM, Povoski SP, Lipari AM, … Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Pain, depression, and fatigue: Loneliness as a longitudinal risk factor. Health Psychology. 2014;33(9):948–957. doi: 10.1037/a0034012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, Bennett JM, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: Understanding the role of immune dys-regulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardan-Souraki M, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Asadpour I, Mohammadpour RA, Khani S. A review of marital intimacy-enhancing interventions among married individuals. Global Journal of Health Science. 2016;8(8):74. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n8p74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandker M, Brady SS, Vitonis AF, MacLehose RF, Stewart EG, Harlow BL. The influence of depression and anxiety on risk of adult onset vulvodynia. Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;20(10):1445–1451. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsberg S. Just ask! Talking to patients about sexual function. Sexuality, Reproduction and Menopause. 2004;2(4):199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Landmark T, Romundstad P, Borchgrevink PC, Kaasa S, Dale O. Associations between recreational exercise and chronic pain in the general population: Evidence from the HUNT 3 study. PAIN®. 2011;152(10):2241–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry T, Bergeron S. How young does vulvo-vaginal pain begin? Prevalence and characteristics of dyspareunia in adolescents. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(4):927–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laryea M, Gien L. The impact of HIV-positive diagnosis on the individual, Part 1: Stigma, rejection, and loneliness. Clinical Nursing Research. 1993;2(3):245–263. doi: 10.1177/105477389300200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leusink P, Kaptheijns A, Laan E, van Boven K, Lagro-Janssen A. Comorbidities among women with vulvovaginal complaints in family practice. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(2):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren BM, Sundbaum J, Eriksson M, Graneheim UH. Looking at the world through a frosted window: Experiences of loneliness among persons with mental ill-health. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2014;21(2):114–120. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Grana G, Fox K. Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: Patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychology. 2005;24:635–641. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz SM, Gonzalez JS, Wilkinson JL, Safren SA. A review of treating depression in diabetes: Emerging findings. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM. The “relative” efficacy of involving family in psychosocial interventions for chronic illness: Are there added benefits to patients and family members? Families, Systems, & Health. 2005;23:312–328. [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychology. 2004;23:599–611. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, Saghafi EM. Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(3):325–342. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;15(3):219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Vowles KE. Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: Model, process, and progress. American Psychologist. 2014;69(2):178–187. doi: 10.1037/a0035623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWhirter BT, Horan JJ. Construct validity of cognitive-behavioral treatments for intimate and social loneliness. Current Psychology. 1996;15(1):42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Meana M, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen DR. Biopsychosocial profile of women with dyspareunia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;90(4):583–589. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)80136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muise A, Bergeron S, Impette EA, Rosen NO. The costs and benefits of communal motivation for couples coping with vulvodynia. Health Psychology. 2017;36:819–827. doi: 10.1037/hea0000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Cucinella L, Martella S, Rossi M, Tiranini L, Martini E. Female sexual dysfunction (FSD): Prevalence and impact on quality of life (QoL) Maturitas. 2016;94:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen RH, Ecklund AM, MacLehose RF, Veasley C, Harlow BL. Co-morbid pain conditions and feelings of invalidation and isolation among women with vulvodynia. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2012;17(5):589–598. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.647703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes R, Kathol RG. Depression and cancer. Psychiatric Developments. 1985;4(2):77–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylanderlundqvist E, Bergdahl J. Vulvar vestibulitis: Evidence of depression and state anxiety in patients and partners. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2003;83(5):369–373. doi: 10.1080/00015550310003764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: Meta-analyses. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2006;36(1):13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN. Falling through the cracks: The gaps between depression prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and response in HIV care. AIDS. 2012;26(5):656. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283519aae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Perlman D. Perspective on loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1982. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Maihoefer CC, Lawrence SM. Validation of the depression item bank from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) in a three-month observational study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;56:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROMIS: Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. PROMIS depression scoring manual. 2015a Sep 9; https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%20Depression%20Scoring%20Manual.pdf.

- PROMIS: Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Sexual function and satisfaction measures user manual. 2015b Jul 8; https://assessmentcenter.net/documents/Sexual%20Function%20Manual.pdf.

- Pukall CF, Goldstein AT, Bergeron S, Foster D, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S, et al. Vulvodynia: Definition, prevalence, impact, and pathophysiological factors. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(3):291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualter P, Brown SL, Munn P, Rotenberg KJ. Childhood loneliness as a predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms: An 8-year longitudinal study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19(6):493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph ME, Reddy DM. Sexual functioning in women with chronic pelvic pain: The impact of depression, support, and abuse. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43(1):38–45. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;32(2):118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen NO, Rancourt KM, Corsini-Munt S, Bergeron S. Beyond a “woman’s problem”: The role of relationship processes in female genital pain. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2014;6(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum TY. An integrated mindfulness-based approach to the treatment of women with sexual pain and anxiety: Promoting autonomy and mind/body connection. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2013;28(1–2):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(3):472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos PR, Capote JRFG, Jr, Cavalcanti JU, Vieira CB, Rocha ARM, Apolônio NAM, et al. Sexual dysfunction predicts depression among women on hemodialysis. International Urology and Nephrology. 2013;45(6):1741–1746. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnatz PF, Whitehurst SK, O’Sullivan DM. Sexual dysfunction, depression, and anxiety among patients of an inner-city menopause clinic. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(10):1843–1849. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C. Social skills, stressful life events, and the development of psychosocial problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1999;18(1):14–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shindel AW, Ando KA, Nelson CJ, Breyer BN, Lue TF, Smith JF. Medical student sexuality: How sexual experience and sexuality training impact US and Canadian medical students’ comfort in dealing with patients’ sexuality in clinical practice. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(8):1321. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e6c4a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindel AW, Parish SJ. Sexuality education in North American medical schools: Current status and future directions (CME) Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(1):3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Lyons A, Ferris J, Richters J, Pitts M, Shelley J, et al. Sexual and relationship satisfaction among heterosexual men and women: The importance of desired frequency of sex. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2011;37(2):104–115. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.560531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KB, Pukall CF. A systematic review of relationship adjustment and sexual satisfaction among women with provoked vestibulodynia. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48(2–3):166–191. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.555016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobecki JN, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, Lindau ST. What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex 1: Results of a national survey of US obstetrician/gynecologists. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9(5):1285–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH. Sex and relationships. New York: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(3):190–196. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson KR, Meston CM. Consequences of impaired female sexual functioning: Individual differences and associations with sexual distress. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2012;27(4):344–357. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2001;17(1):52–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedhem C, Eckert G, Wijma B. Living with genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder in a heterosexual relationship: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of interviews with either women. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2013;28(4):336–349. [Google Scholar]

- Œwitaj P, Grygiel P, Anczewska M, Wciórka J. Loneliness mediates the relationship between internalised stigma and depression among patients with psychotic disorders. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2014;60(8):733–740. doi: 10.1177/0020764013513442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatlilioğlu K. The effect of cognitive behavioral oriented psychoeducation program on dealing with loneliness: An online psychological counseling approach. Education. 2013;134(1):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- ter Kuile MM, Both S, van Lankveld JJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33(3):595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhalst J, Klimstra TA, Luyckx K, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Goossens L. The interplay of loneliness and depressive symptoms across adolescence: Exploring the role of personality traits. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41(6):776–787. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9726-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Katon WJ. Dissociation in women with chronic pelvic pain. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):534. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Zakalik RA. Adult attachment, social self-efficacy, self-disclosure, loneliness, and subsequent depression for freshman college students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(4):602. [Google Scholar]

- Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Bruner DW, Cyranowski JM, Dombeck CB, Hahn EA, … Reese JB. Development and initial validation of the PROMIS® sexual function and satisfaction measures version 2.0. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2015;12(9):1961–1974. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherow MP, Chandraiah S, Seals S, Sarver DE, Parisi KE, Bugan A. Relational intimacy mediates sexual outcomes associated with impaired sexual function: Examination in a clinical sample. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2017;14:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannes AM, Alexopoulos GS. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Impact on the course of the disease and health outcomes. Drugs and Aging. 2014;31(7):483–492. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0186-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]