Summary

Skeletal muscle cells (myofibers) are rod-shaped multinucleated cells surrounded by an extracellular matrix (ECM) basal lamina. In contrast to other cell types, nuclei in myofibers are positioned just below the plasma membrane at the cell periphery. Peripheral nuclear positioning occurs during myogenesis and is driven by myofibril crosslinking and contraction. Here we show that peripheral nuclear positioning is triggered by local accumulation of fibronectin secreted by myofibroblasts. We demonstrate that fibronectin via α5-integrin mediates peripheral nuclear positioning dependent on FAK and Src activation. Finally, we show that Cdc42, downstream of restricted fibronectin activation, is required for myofibril crosslinking but not myofibril contraction. Thus we identify that local activation of integrin by fibronectin secreted by myofibroblasts activates peripheral nuclear positioning in skeletal myofibers.

Keywords: nuclear movement, muscle development, extracellular matrix signaling, fibronectin, cell-cell interaction, nuclear position

Highlights

-

•

Myofibroblasts deposit extracellular fibronectin at the periphery of muscle cells

-

•

Fibronectin hotspots are sufficient to trigger local peripheral nuclear positioning

-

•

α5β1 integrin via FAK, Src, and Cdc42 organize desmin for nuclear movement

A hallmark of skeletal muscle cells is the position of nuclei at the cell periphery. Roman et al. show that myofibroblasts deposit extracellular components—fibronectin—at the surface of developing muscle cells to locally attract myonuclei to the cell periphery.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is a mechanical system designed to generate force for locomotion and posture. Several cell types participate in the tissue's development, regeneration, and homeostasis to endure stress and strain from muscle usage. Muscle cells (myofibers) responsible for contraction are multinucleated and rod-shaped with the particularity of having their nuclei positioned at the periphery, in close contact with the plasma membrane (Cadot et al., 2015). Nuclei are equally distributed in fully matured myofibers apart from specialized regions such as myotendinous and neuromuscular junctions. It is during myogenesis in newborn mice that nuclei transition from the center to the periphery of the myofiber due to myofibril crosslinking, myofibril contraction, and local changes of nuclear stiffness (Harris et al., 1989, Roman et al., 2017, Wada et al., 2003). Myofibril crosslinking is mediated by desmin organization at the z lines, which is the downstream result of a pathway involving N-Wasp, the Arp2/3 complex containing Arpc5L and γ-actin. This pathway is disrupted in patients with BIN1 mutations, found in centronuclear myopathies (CNM), and leads to nuclear-positioning defects (D’Alessandro et al., 2015, Falcone et al., 2014). How peripheral nuclear positioning is activated is unknown, but proper positioning of nuclei is important for muscle function (Gimpel et al., 2017, Metzger et al., 2012).

Interaction of myofibers with the extracellular matrix (ECM) is required for myofiber formation and function. These interactions are mediated by different adhesion receptors, of which integrins are one of the main families (Goody et al., 2015). Integrins are divalent receptors (α and β chains) that bind to ECM proteins resulting in intracellular signaling cascades that play biological functions during muscle development, homeostasis, and regeneration (Campbell and Humphries, 2011). α5β1-integrin is activated by fibronectin and is mostly expressed during development. Whereas α5 knockout mice die prior to muscle formation, chimeric α5 mice (−/−; +/+) form myofibers with multiple defects, including mispositioned nuclei (Taverna et al., 1998). The importance of α5β1-integrin during development is not surprising, as fibronectin is the main ECM component surrounding myofibers and is laid down by different cell types including fibroblasts and myofibroblasts (Eyden, 2008, Gulati, 1985, Torr et al., 2015). Integrins can activate, among other effectors, small Rho guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases), which are the main switches regulating the cytoskeleton (Huveneers and Danen, 2009, Huveneers and Danen, 2009). There are three classes of small Rho GTPases; Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 (Heasman and Ridley, 2008, Ridley and Hodge, 2016). Cdc42 can directly activate N-Wasp to stimulate actin dynamics (Rohatgi et al., 1999). Here we tested whether local activation of integrins by fibronectin can activate peripheral nuclear positioning.

Results

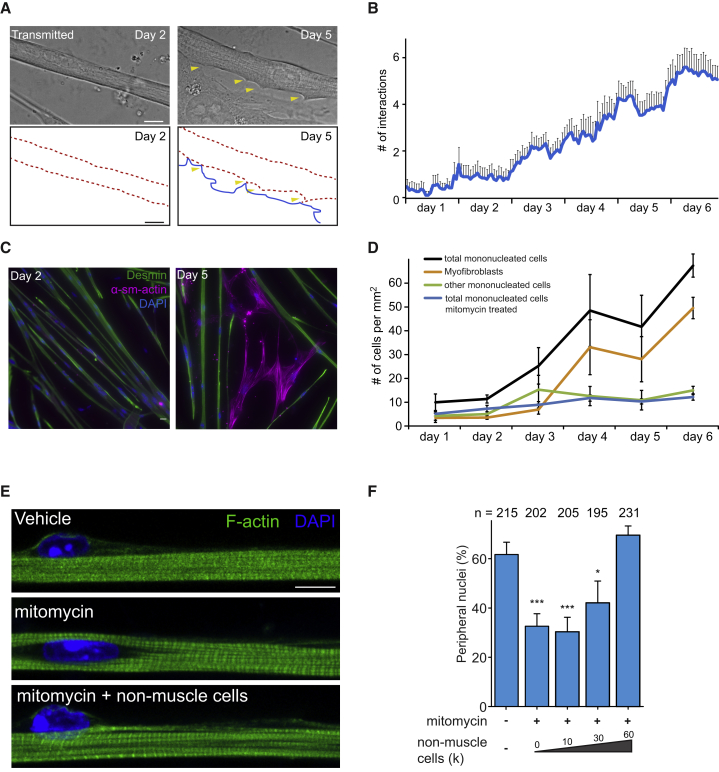

Myofibroblasts Trigger Peripheral Nuclear Positioning in Skeletal Muscle Fibers

To study the mechanisms of skeletal muscle differentiation, we used an in vitro system in which primary muscle cells (myoblasts) isolated from muscle are differentiated into highly matured myofibers with peripheral nuclei (Falcone et al., 2014, Pimentel et al., 2017). In this system, myoblasts fuse at day 0 forming multinucleated cells that elongate into myotubes with spread and centrally located nuclei. Nuclei move to the periphery of the myotube around at day 4–5, resulting in the formation of myofibers. Non-muscle cells are also present, as a pure culture of primary myoblasts is not obtained with this protocol (Falcone et al., 2014, Roman et al., 2017). These cells proliferate and interact with myotubes with the number of interactions increasing over time (Figures 1A and 1B). When we normalized the number of interactions relative to the number of mononucleated cells, we observed an increase of interactions between day 4 and day 6, at the onset of peripheral nuclear movement per mononucleated cell (Figure S1A).

Figure 1.

Non-muscle Cells Are Involved in Nuclear Movement to the Periphery of Myofibers

(A) Representative transmitted image highlighting the interactions (yellow arrowheads) between non-muscle cells and myofibers at day 2 (no interaction, left) and day 5 (interactions, right). Bottom panels depict non-muscle cell (blue) and myofiber (dashed red) interaction as outlines from upper panels. Scale bars, 10 μm.

(B) Quantification of number of interactions between myofibers and non-muscle cell during muscle development. Data from three independent experiments with n = 19 myofibers quantified. Error bars correspond to SEM.

(C) Representative immunofluorescence image of in vitro culture containing myofibers and non-muscle cells stained either for α-smooth muscle actin (α-sm-actin, magenta), desmin (green), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Quantification of number of myofibroblasts and other non-muscle cells per mm2, treated with vehicle or mitomycin, during muscle development. Data collected from three independent experiments with at least 12 areas of 322 mm2 for each condition. Error bars correspond to SEM.

(E) Representative immunofluorescence image of 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, mitomycin, or mitomycin supplemented with untreated non-muscle cells and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F) Quantification of peripheral nuclei in 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, mitomycin, or mitomycin supplemented with untreated non-muscle cells. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

To better understand the nature of the proliferative mononucleated cell population, we performed immunostainings against α-smooth muscle actin, CD31, MAP2, and desmin to identify myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, neuronal cells, and myocytes, respectively. At day 1, 45% of non-muscle cells (desmin negative) were positive for α-smooth muscle actin (i.e., myofibroblasts), whereas no mononucleated cell was expressing CD31 or MAP2 (Figures 1C and 1D). By day 5, the proportion of myofibroblasts increased to 75% of the total mononucleated cell population, making myofibroblasts the major proliferating cell type alongside maturing myotubes in vitro (Figure 1D). We also observed myofibroblasts in between myofibers in muscle of newborn mice (Figure S1B).

Due to the observed interaction between proliferating myofibroblasts and myotubes, we wondered whether the proliferation of myofibroblasts is involved in myofiber differentiation. To this end, we treated the in vitro cultures with mitomycin for 2 hr at day 0 before differentiation, during myoblast fusion. Mitomycin prevents the proliferation of cells such as undifferentiated myoblasts and other mononucleated cells without affecting differentiated myoblasts and myotubes, since these cells are post-mitotic (Cooper et al., 2004, Falcone et al., 1984, Pajcini et al., 2008). As expected, mitomycin treatment resulted in a dramatic reduction of myofibroblasts in the plate (Figures 1D and S1C). Bromodeoxyuridine pulse experiments showed that most of the myoblasts were differentiated at day 0, and upon mitomycin treatment we observed a minor reduction of undifferentiated myoblasts (Figures S1D and S1E). Myotube formation and elongation, myofibrillogenesis, and transverse triad formation were unaffected by mitomycin treatment, indicating that overall myofiber development was unaltered (Figures 1E, S1F, and S1G). Strikingly, nuclear movement to the periphery of myotubes was inhibited in cultures treated with mitomycin when compared with untreated cultures (Figures 1E and 1F). To confirm the involvement of non-muscle cells in nuclear positioning, we tested whether the addition of proliferative non-muscle cells to mitomycin-treated cultures was able to restore peripheral nuclear positioning. We found that increasing the number of non-muscle cells leads to an increase in the number of peripheral nuclei (Figures 1E and 1F), confirming that non-muscle cells are important for nuclear positioning.

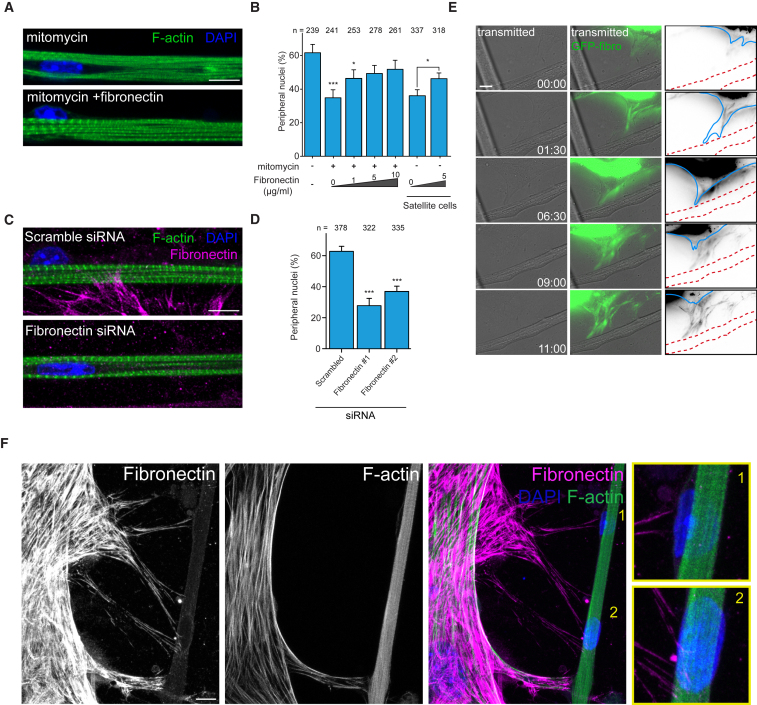

Fibronectin Is Required for Peripheral Nuclear Positioning in Skeletal Muscle Fibers

Myofibroblasts and fibroblasts secrete fibronectin (Eyden, 2008, Torr et al., 2015). We therefore validated that at day 5, the fibronectin amount increased when compared with day 2 or cultures treated with mitomycin (Figure S2A).

We tested whether fibronectin played a role in peripheral nuclear positioning by adding increasing amounts of fibronectin to mitomycin-treated myotubes. Fibronectin addition restored nuclear positioning at the periphery of myofibers to levels similar to those of untreated cultures (Figures 2A and 2B). We also purified satellite cells, myoblast precursors, from Pax7-nGFP mice (Sambasivan et al., 2009) (Figures S2B–S2E) and found that cultures obtained from satellite cells displayed a peripheral nuclear phenotype similar to that of the mitomycin-treated cultures. We were able to restore peripheral nuclear positioning by adding fibronectin to these satellite cell-derived cultures (Figure 2B). Additions of laminin or collagen, other ECM proteins, were not sufficient to restore peripheral nuclear positioning in mitomycin-treated cultures (Figure S2F).

Figure 2.

Fibronectin Secreted by Myofibroblasts Is Required for Peripheral Nuclear Positioning

(A) Representative immunofluorescence image of 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, mitomycin, or mitomycin supplemented with fibronectin, and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Quantification of peripheral nuclei in 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, mitomycin, or mitomycin supplemented with fibronectin or Pax7 sorted cells (satellite cells) supplemented or not with fibronectin. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(C) Representative immunofluorescence image of 10-day myofibers knocked down for scrambled or fibronectin and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green), fibronectin (magenta), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Quantification of peripheral nuclei in 10-day myofibers from a culture knocked down for scrambled or fibronectin. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(E) Time-lapse (hr:min) transmitted light images of myofibroblasts transfected with GFP-fibronectin (green) locally depositing fibronectin on myofiber surface. Right-hand panels depict myofibroblast (blue), myofiber (dashed red), and fibronectin (black) interaction as outlines from the panels on the left. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F) Representative immunofluorescence z-projection images of a 5-day myofiber and myofibroblast stained for F-actin (green), fibronectin (magenta), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Yellow boxes represent 3× magnifications to highlight nuclei positioned at the periphery of the myofiber (1. nucleus is on the left; 2, nucleus is on the top). Scale bar, 10 μm.

To further support the role for fibronectin in peripheral nuclear positioning, we knocked down fibronectin in our cultures and observed that peripheral nuclear positioning was also inhibited (Figures 2C, 2D, and S2G).

We next tested whether fibronectin is locally deposited by myofibroblasts to promote peripheral nuclear positioning. We performed live imaging of myofibroblasts overexpressing GFP-fibronectin at day 4 and observed that myofibroblasts deposit fibronectin next to myotubes upon interaction (Figure 2E). Using immunofluorescence microscopy, we also observed extracellular fibronectin bundles touching myofibers at areas with nuclei (Figure 2F). Together these data suggest that myofibroblasts locally deposit fibronectin at the surface of myotubes.

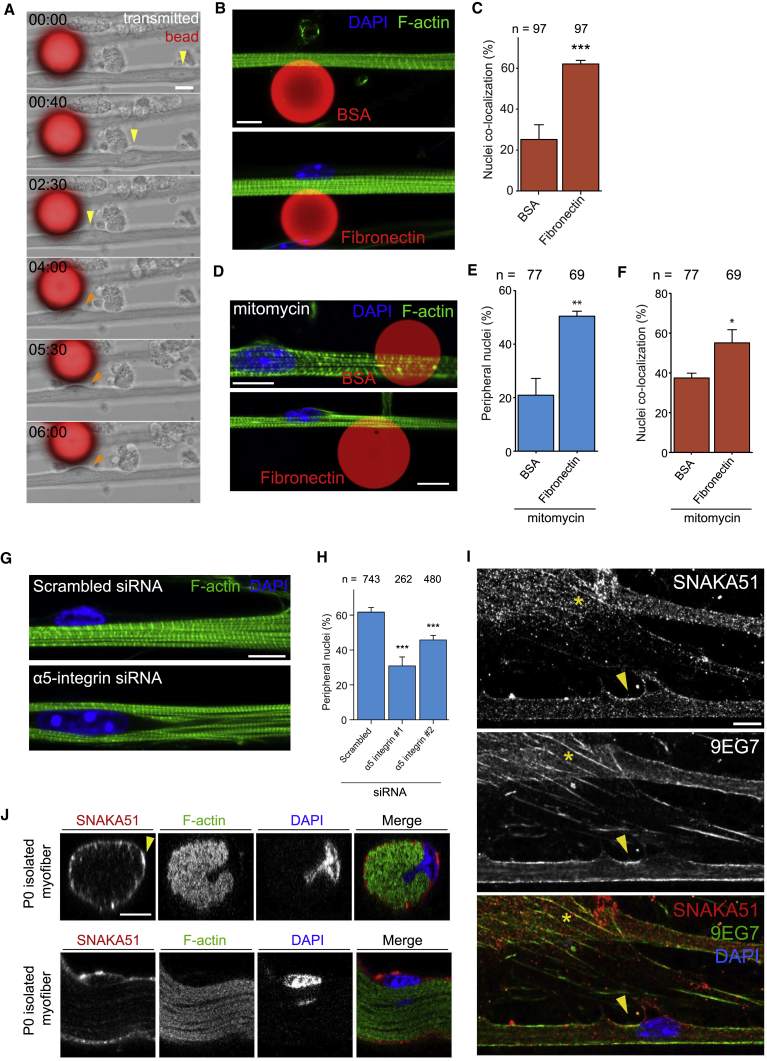

We next determined whether local accumulation of fibronectin is involved in peripheral nuclear positioning. To test this hypothesis, we performed live imaging of myotubes cultured alongside 20-μm polystyrene beads pre-coated with fibronectin, and observed nuclei migrating toward the bead and then to the periphery (Figure 3A). We found that peripheral nuclei were localized in proximity to fibronectin-coated beads for 60% of beads touching myotubes, whereas only 24% of control beads (coated with bovine serum albumin-BSA) co-localized with peripheral nuclei (Figures 3B and 3C). Moreover, fibronectin-coated beads were able to rescue peripheral nuclei in mitomycin-treated cultures (Figures 3D–3F). Overall, these results strongly suggest that fibronectin can locally trigger peripheral nuclear positioning.

Figure 3.

Local Accumulation of Fibronectin Triggers Peripheral Nuclear Positioning via α5-Integrin

(A) Time-lapse (hr:min) images of myofiber cultures (transmitted) 20-μm beads coated with fibronectin (fluorescence, red). Note that centrally located nucleus (yellow arrowhead) moves toward the bead and to the periphery once it reaches the bead (orange arrowhead). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Representative immunofluorescence z-projection images of 10-day myofibers cultured with 20-μm beads coated with either BSA (top) or fibronectin (bottom) and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(C) Quantification of number of nuclei from 10-day myofibers in proximity to BSA- or fibronectin-coated beads. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) Representative immunofluorescence z-projection images of 10-day myofibers treated with mitomycin and cultured with 20-μm beads coated with either BSA or fibronectin and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Quantification of number of peripheral nuclei from 10-day myofibers treated with mitomycin and in contact with BSA- or fibronectin-coated beads. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗∗p < 0.01.

(F) Quantification of number of nuclei from 10-day myofibers treated with mitomycin in proximity to BSA- or fibronectin-coated beads. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗p < 0.05.

(G) Representative immunofluorescence image of 10-day myofibers knocked down for scrambled or α5-integrin and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(H) Quantification of peripheral nuclei in 10-day myofibers knocked down for scrambled or α5-integrin. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(I) Representative immunofluorescence image of 5-day myofibers stained for SNAKA51 (α5-integrin, red), 9EG7 (β-integrin, green), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Yellow arrowhead indicates α5-integrin activation in myofibers whereas yellow asterisk indicates fibrillar adhesions in myofibroblasts. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(J) Representative orthogonal (top) and side (bottom) immunofluorescence image of isolated myofibers from newborn mice stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green), SNAKA51 (α5-integrin, red), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Yellow arrowhead indicates α5-integrin accumulation. Scale bar, 10 μm.

α5-Integrin Is Activated by Fibronectin for Nuclear Positioning

The main receptor of fibronectin in cells is the integrin family of divalent receptors composed of an α and a β chain (Campbell and Humphries, 2011). Within this extensive family, α5β1 is one of the prevalent fibronectin receptors. We therefore depleted myotubes of the α5-integrin using small interfering RNA and observed a decrease in peripheral nuclei with no effect on myofibril formation (Figures 3G, 3H, and S2H). To confirm the involvement of α5-integrin in nuclear movement to the periphery, we added beads coated with BSA or fibronectin to α5-integrin knocked-down myotubes and found that neither beads rescued peripheral nuclear positioning (Figures S2I–S2K). Interestingly, nuclei still co-localized with fibronectin-coated beads but not with BSA-coated beads (Figures S2I and S2K), suggesting that α5-integrin is required for peripheral nuclear positioning downstream of fibronectin but that another mechanism involves attracting nuclei to fibronectin hotspots. We confirmed the activation of the α5-integrin receptor by performing a 9EG7 (β-integrin) and SNAKA51 (activated α5-integrin) staining (Clark et al., 2005) and observed co-localization in myofiber nuclei moving to the periphery (Figure 3I). Co-localization of 9EG7 and SNAKA51 at fibrillar adhesions was also observed in myofibroblasts, as previously described in human and mouse cells (Lagana et al., 2006). Enrichment of the activated α5-integrin was also observed at the site of nuclear movement to the periphery in vivo using isolated myofibers from newborn mice (Figure 3J).

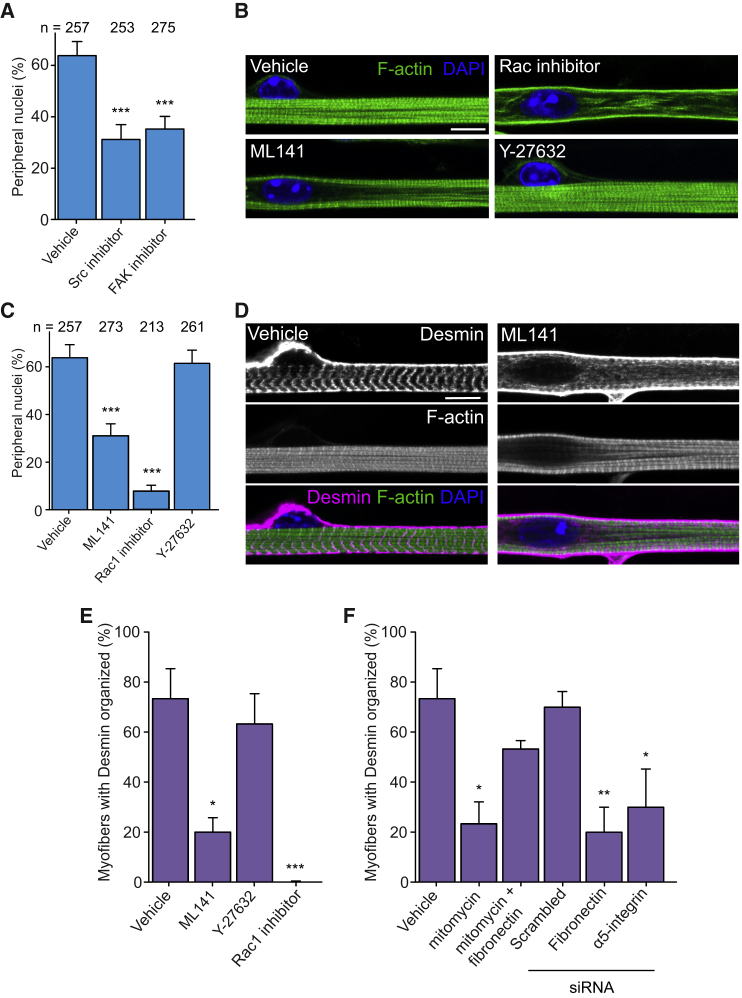

Integrin activation recruits and activates FAK and Src family kinases by phosphorylation (Huveneers and Danen, 2009). The FAK-Src complex phosphorylates paxillin, which then recruits β-Pix to activate Cdc42 (Osmani et al., 2006). We used specific inhibitors of Src family kinases (PPI) and FAK to test their role on peripheral nuclear positioning (Hanke et al., 1996, Slack-Davis et al., 2007). Upon incubation with the inhibitors at day 4.5, we found that peripheral nuclear positioning was inhibited (Figure 4A). Surprisingly, transverse triad formation was not inhibited upon Src and FAK inhibition, suggesting a specific role for these proteins on nuclear positioning and not on transverse triad formation and development (Figure S3A).

Figure 4.

Cdc42 Downstream of Fibronectin and Integrin Activation Is Required to Organize Desmin in Myofibers

(A) Quantification of peripheral nuclei in 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, PPi (Src inhibitor), or FAK inhibitor. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(B) Representative immunofluorescence image of 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, Cdc42 inhibitor (ML141), Rac1 inhibitor, or Rock inhibitor (Y-27632) and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(C) Quantification of peripheral nuclei in 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle, ML141, Rac1 inhibitor, or Y-27632. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from indicated number of nuclei (n) for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) Representative immunofluorescence image of 10-day myofibers treated with vehicle or ML141 and stained for F-actin (myofibrils, green), desmin (magenta), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E and F) Quantification of transverse desmin organization in 10-day myofibers from cultures treated with and knocked down for indicated conditions. Data from three independent experiments were combined and error bars represent SEM from at least 30 myofibers for each cohort. Unpaired t test was used to determine statistical significance, where ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Cdc42, but Not Rho and Rac, Is Involved in Peripheral Nuclear Positioning by Regulating Desmin Crosslinking

Fak and Src family kinases are known mediators of integrin signaling that activate small Rho GTPases (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) (Huveneers and Danen, 2009, Osmani et al., 2006). We thus used inhibitors of Rho kinase, activated by Rho (Y-27632), Rac1 (NSC23766), and Cdc42 (ML141) (Gao et al., 2004, Surviladze et al., 2010, Uehata et al., 1997), to study the role of small Rho GTPases on localization of peripheral nuclei. We found that inhibition of Rho kinase with Y-27632 did not inhibit peripheral nuclear positioning or transverse triad formation (Figures 4B, 4C, and S3A). To validate that Y-27632 was inhibiting Rho kinase under our culture conditions, we confirmed the reduction of actin stress fibers in cells treated with Y-27632 when compared with vehicle-treated cells, as previously described (Figure S3B) (Uehata et al., 1997). On the other hand, treatment of cells with Rac1 inhibitor inhibited peripheral nuclear positioning, transverse triad formation, and myofibrillogenesis, suggesting an overall arrest in myotube development (Figures 4B, 4C, and S3A). Finally, inhibition of Cdc42 upon incubation with ML141 specifically prevented peripheral nuclear positioning, but not triad formation, as observed for the inhibition of Fak and Src family kinases (Figures 4A, 4C, and S3A). In addition, BSA- or fibronectin-coated beads did not restore peripheral nuclei in ML141-treated cultures (Figures S2L and S2M). Therefore, Cdc42 is probably activated downstream of the fibronectin pathway to specifically regulate peripheral nuclear positioning, but not transverse triad formation, in skeletal muscle cells.

We previously identified that peripheral nuclear positioning involves the activation of N-Wasp and requires desmin crosslinking of myofibrils mediated by the Arp2/3 complex and γ-actin. We also found a role for myofibril contraction on peripheral nuclear positioning, independent of the Arp2/3 complex and γ-actin (Falcone et al., 2014, Roman et al., 2017).

Since N-Wasp is a Cdc42 effector and activates the Arp2/3 complex for actin nucleation (Rohatgi et al., 1999), we hypothesized that Cdc42 is involved in desmin organization. Inhibition of Cdc42 using ML141 prevented the organization of desmin at the z lines when compared with control (Figures 4D and 4E). On the other hand, Rho kinase inhibition with Y-27632 did not have an effect on desmin organization. We also observed that Rac1 inhibition displayed disorganized desmin probably due to its overall role on muscle development (Figure 4E). Therefore Cdc42 is involved in desmin organization, which is required to crosslink myofibrils.

We next tested whether fibronectin, via integrins upstream of Cdc42, is also involved in desmin organization. We found that treatment of cultures with mitomycin, a condition in which peripheral nuclear positioning is inhibited (Figure 2B), prevented desmin organization (Figure 4F). The addition of fibronectin restored desmin organization whereas knockdown of fibronectin or α5-integrin prevented desmin organization (Figure 4F). We previously demonstrated that myofibril contraction is also required for peripheral nuclear positioning (Roman et al., 2017). We therefore measured optogenetically induced contractions in myotubes treated with vehicle, mitomycin, ML141, or depleted for α5-integrin and found that myofibril contraction was not impaired since all the cohorts contracted and fatigue experiments revealed no difference of contractile capacity (Figures S3C and S3D). Furthermore, the increase in calcium concentration upon contraction was measured with GCaMP6f genetically encoded sensor and was not affected by the inhibition of Cdc42 (Figures S3E and S3F). These data rule out a role for the fibronectin pathway in myofibril contraction. Overall, these results suggest that the fibronectin-Cdc42 pathway locally controls nuclear movement to the periphery by organizing desmin, thereby inducing myofibril crosslinking.

Discussion

Peripheral nuclear positioning in myofibers is a hallmark of muscle formation. Here we show that peripheral nuclear positioning in skeletal muscle fiber is locally activated by fibronectin via α5-integrin, FAK, and Src, upstream of Cdc42. Furthermore, we show that Cdc42 is involved in desmin crosslinking of myofibrils, required for peripheral nuclear positioning (Figure S4).

During myofiber regeneration, fibroblasts and myofibroblasts have been shown to produce fibronectin to form the ECM and the basal lamina, and to be required for proper propagation of muscle precursor cells during regeneration upon injury (Murphy et al., 2011). Furthermore, fibronectin has also been implicated in age-dependent muscle regeneration by the activation of integrin signaling via p38 and ERK/MAPK in muscle precursor cells (Lukjanenko et al., 2016). We now demonstrate that fibronectin secreted by myofibroblasts also has a direct role on myofiber differentiation by locally activating integrin via FAK, Src, and the small GTPase Cdc42. Cdc42 can then activate myofibril crosslinking via its effector N-Wasp, leading to desmin remodeling required for peripheral nuclear movement (Falcone et al., 2014, Roman et al., 2017). It would be interesting in the future to determine whether integrin signaling in muscle precursor cells also leads to small GTPase activation and cytoskeleton remodeling, as we demonstrated for myofibers (Lukjanenko et al., 2016, Roman et al., 2017).

Our results also support a restricted role for fibronectin on peripheral nuclear positioning. In myofibers, peripheral nuclei are distributed at the periphery to maximize the area of influence of each nucleus (Bruusgaard et al., 2006). However, some of these nuclei are specifically clustered at the neuromuscular junction and are also found along the blood vessels (Ralston et al., 2006, Sanes and Lichtman, 2001). Fibronectin is known to accumulate at the neuromuscular junction and in the basal membrane secreted by endothelial cells, in addition to myofibroblasts (Daramola et al., 1997, Sanes, 2003). Therefore the mechanism described here can also be involved in the positioning of the nucleus at the neuromuscular junction and near the blood vessels that surround myofibers. The position of nuclei in these specialized regions could be essential for cell-cell communication and collective cellular behavior at the tissue level.

Upon reaching the myofiber periphery, nuclei still move longitudinally, although to a much smaller extent than when nuclei are still in the center of the myotube (Englander and Rubin, 1987, Falcone et al., 2014, Gache et al., 2017). How peripheral nuclear movement along the myofiber occurs is unknown. It will therefore be important to determine how these unknown mechanisms driving nuclear movement crosstalk with local fibronectin-triggered signaling.

Small GTPases are master regulators of the cytoskeleton, and Cdc42 in particular has been associated with the establishment and control of cell polarity (Etienne-Manneville, 2004). Cdc42 has also been implicated in nuclear positioning during cell migration via nucleus-cytoskeleton connections, probably activated by integrin signaling, leading to cell polarization (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001, Gomes et al., 2005, Luxton et al., 2010). The pathway and mechanism we describe here shows that local activation of integrin in myofibers via specific secretion of fibronectin by myofibroblasts can locally trigger nuclear positioning. During cell migration, similar local and specific integrin activation remains to be determined.

The nucleus is positioned within cells taking into account tissue architecture and asymmetry (Gundersen and Worman, 2013). Here we describe that local remodeling of fibronectin-containing ECM by myofibroblasts can directly stimulate nuclear movement and positioning toward the site of ECM remodeling. We thus propose a mechanism by which cells can sense tissue architecture and regulate nuclear positioning in accordance with a local cue established by fibronectin-secreting cells. Future work should address whether the mechanism we describe herein also takes place in other nuclear-positioning events that occur during development and tissue homeostasis.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-α-smooth muscle actin | Abcam | Cat #ab5694; RRID: AB_2223021 |

| Mouse anti-Desmin, Clone D33 | Dako | Cat #M0760; RRID: AB_2335684 |

| Rabbit anti-Fibronectin | Millipore | Cat #AB2047; RRID: AB_2278547 |

| Goat anti-CD31 | R&D Systems | Cat #AF3628; RRID: AB_2161028 |

| Mouse anti-MAP2 | Sigma | Cat #M2320; RRID: AB_609904 |

| Rabbit anti-Triadin | Dr. Isabelle Marty | N/A |

| Mouse anti-MyoD | BD Pharmingen | Cat #554130; RRID: AB_395255 |

| Rabbit anti-BrdU | Abcam | Cat #ab152095 |

| Mouse anti-Integrin α5, clone SNAKA51 | Millipore | Cat #MABT201 |

| Rat anti-Integrin β1, clone 9EG7 | BD Pharmingen | Cat #550531; RRID: AB_393729 |

| Goat anti-Tensin | Abcam | Cat #ab52008; RRID: AB_883131 |

| Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21202; RRID: AB_141607 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21424; RRID: AB_141780 |

| Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21206; RRID: AB_2535792 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21429; RRID: AB_2535850 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A10042; RRID: AB_2534017 |

| Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21432; RRID: AB_2535853 |

| Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21447; RRID: AB_2535864 |

| Donkey anti-Rat IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #A21208; RRID: AB_2535794 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Collagenase type I | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #C0130 |

| Dispase | Roche | Cat #04942078001 |

| Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) with GlutaMAX | Invitrogen | Cat #31980022 |

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS) | Eurobio | Cat #CVFSVF00-01 |

| Penicillin/streptomycin (Penstrep) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #15140122 |

| Horse serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #26050088 |

| Chicken embryo extract | This paper | N/a |

| Matrigel | Corning | Cat #354230, lot 6305006 |

| Recombinant Rat Agrin | R&D systems | Cat #550-AG-100 |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent | Invitrogen | Cat #L3000015 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent | Invitrogen | Cat #13778150 |

| Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium | GIBCO | Cat #31985070 |

| Goat serum | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #G9023 |

| Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #A7906 |

| Saponin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #47036 |

| Fluoromount-G | Invitrogen | Cat #00-4958-02 |

| Mitomycin C | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #M7949 |

| Fibronectin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #F1141 |

| Laminin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #L2020 |

| Collagen | Ibidi | Cat #50201 |

| Cilengitide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #SMG 1594 |

| ML141 (Cdc42 inhibitor) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #SML0407 |

| Rac1 inhibitor | Merck Millipore | Cat #553502 |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Merck Millipore | Cat #688001 |

| FAK inhibitor | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #PZ0117 |

| Src inhibitor,PPi | Merck Millipore | Cat #539571 |

| Nonidet P-40 | Euromedex | Cat #9016-45-9 |

| Sodium deoxycholate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #30970 |

| Urea | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #U1250 |

| Glutaraldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat #16216 |

| Formamide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #47671 |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #P2139 |

| Phalloidin 488 Alexa Fluor | Life Technologies | Cat #A12379; RRID: AB_2315147 |

| Phalloidin 555 Alexa Fluor | Life Technologies | Cat #A34055 |

| 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #32670 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| RNeasy micro kit | Qiagen | Cat #50974004 |

| High capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit | Applied Biosystems | Cat #4387406 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | Charles River | Strain code: 027 |

| Mouse: Pax7-nGFP | (Sambasivan et al., 2009) | RRID: MGI:5308730 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| siRNA non-targeting sequence: Scrambled UUCUCCGAACGU GUCACGUTT, ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

Genecust | N/A |

| siRNA targeting sequence: mouse α5 Integrin (Itga5) #1 CCUCAGG AAUGAAUCAGAAtt |

Ambion | cat # 4390771 s68428 |

| siRNA targeting sequence: mouse α5 Integrin (Itga5) #2 GGGAGUC GUAUUUAUAUUCtt |

Ambion | cat #AM16708 155908 |

| siRNA targeting sequence: mouse Fibronectin (Fn1) #1 CCUACAAC AUCAUAGUGGAtt |

Ambion | cat # 4390771 s66183 |

| siRNA targeting sequence: mouse Fibronectin (Fn1) #2 CCGUUUU CAUCCAACAAGAtt |

Ambion | cat # 4390771 s66182 |

| α5-integrin: Forward primer; 5’-AAAGGACCCACAGAATGACCC-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| α5-integrin: Reverse primer; 5’-CCAAAATCTGAGCGGCAAGG-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| Fibronectin: Forward primer; 5’-TGACTGGCCTTACCAGAGGG-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| Fibronectin: Reverse primer; 5’-CATCTGTAGGCTGGTTCAGGC-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| Hypoxanthine Phosphoribosyltransferase 1: Forward primer; 5’-GTTAAGCAGTACAGCCCCAAA-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| Hypoxanthine Phosphoribosyltransferase 1: Reverse primer; 5’-AGGGCATATCCAACAACAAACTT-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| GFP-fibronectin | N/A | Addgene plasmid: Cat #56600 |

| ChR2-GFP | (Zhang et al., 2007) | Addgene plasmid: Cat #20939 |

| GCaMP6f | (Chen et al., 2013) | Addgene plasmid: Cat #40755 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad software | Version 5; RRID:SCR_002798 |

| StepOne Software | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Version 2.3; RRID:SCR_014281 |

| Metamorph | Molecular Devices | RRID: SCR_002368 |

| ZEN software 2012 | Carl Zeiss MicroImaging | RRID:SCR_013672 |

| ZEN software 2.1 (black) | Carl Zeiss MicroImaging | RRID:SCR_013672 |

| FlowJo | FlowJo software | Version 10; RRID:SCR_008520 |

| Fiji | https://fiji.sc | RRID: SCR_002285 |

| Adobe Ilustrator CS5 | Adobe Systems | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Fluorodishes | World Precision Instruments (WPI) | Cat #FD35-100 |

| μ-Slide 8 Well ibiTreat: #1.5 polymer coverslip, tissue culture treated, sterilized | Ibidi | Cat #80826 |

| 37°C/5% CO2 incubator | Okolab | N/A |

| 20x 0.3 NA PL Fluo dry objective | Leica Microsystems | N/A |

| Nikon Ti microscope | Nikon | N/A |

| CoolSNAP HQ2 camera | Roper Scientific | N/A |

| XY-motorized stage | Nikon | N/A |

| Zeiss LSM 710 | Carl Zeiss MicroImaging | N/A |

| Zeiss LSM 880 | Carl Zeiss MicroImaging | N/A |

| 63x 1.4 NA Plan-Apochromat objective | Carl Zeiss MicroImaging | N/A |

| Zeiss Cell Observer Spinning Disk system | Carl Zeiss MicroImaging | N/A |

| Z-piezo | Prior | N/A |

| Spinning Disk CSU-X1M 5000 | Yokogawa | N/A |

| 37°C/5% CO2 incubator | Pekon | N/A |

| EM-CCD camera Evolve 512 | Photometrics | N/A |

| Polystyrene beads | Phosphorex | Cat #1020KB |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Edgar R. Gomes (edgargomes@medicina.ulisboa.pt).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Primary Myoblasts and Mouse Strains

C57BL/6 wild type and Pax7-nGFP mice were previously described (Sambasivan et al., 2009). Briefly, a BAC containing approximately 200 kbp of mouse genomic DNA including the locus encoding Pax7 and sequences both upstream (B12; ∼55 kbp with respect to Pax7 initiator ATG) and downstream (∼60 kbp from terminator codon) on a pBeloBac11 backbone was isolated from a library (129Sv; CITBCJ7-B; Research Genetics; courtesy of M. Cohen-Tannoudji). The BAC was then electroporated into E. coli strain EL 350 and recombined with a nuclear localised EGFP (nGFP; from pCIG, courtesy of A. McMahon) as described (Liu et al., 2003). The targeting vector was designed to introduce nGFP into the first exon of Pax7 gene (mutated initiator ATG and deleted bases 58-94 of exon 1). Tg: Pax7- nGFP transgenic mice were generated (courtesy of Pasteur Transgenic Platform, F. Langa Vives) by microinjection of fertilized eggs (F1: C57BL6:SJL/J) with the engineered circular BAC. C57BL/6 wild type and Pax7-nGFP mice were kept in a specific pathogen free (SPF) Mouse Facility and virus antibody free (VAF) Mouse facility, respectively, and were housed in trios (1 male, two females) for breeding purposes and pups were maintained in the breeding cage until usage. They were housed in individually ventilated cages with standard bedding (corncob) and nesting enrichment (home dome and cotton coccons). Both the animal holding rooms and cages are kept at specific environmental intervals, according to the applicable legislation. Temperature and relative humidity levels are recorded on a daily basis. Temperature is kept at the neutral thermal zone (20-24°C) and relative humidity is maintained in a 50-60% range. The room light cycle is 14h light and 10h dark. The animals have ad libitum access to water supply and standard laboratory chow diet. All procedures using animals were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at Instituto de Medicina Molecular and followed the guidelines of the Decreto-lei n° 113/2013, 7 of August which is the national legislation that transposes the European Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. In vitro myofibers were generated with primary myoblasts isolated from 5 - 7 day old pups of C57BL/6 or Pax7-nGFP mice (Sambasivan et al., 2009). Mouse hind limb muscles tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus, medial and lateral gastrocnemius, vastus medialis and lateralis were isolated by severing the tendons using surgical scissors and tweezers. After hind limb muscles isolation, muscles were minced and digested for 1.5 h in PBS containing 0.5 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma) and 3.5 mg/ml dispase (Roche) at 37°C. Cell suspension was filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer and preplated in IMDM (Invitrogen) + 10%FBS (Eurobio), to discard the majority of fibroblasts and contaminating cells, for 4 h in 37°C/5%CO2. Non-adherent-myogenic cells were collected and plated in IMDM (Invitrogen) + 20% FBS + 1% Chick Embryo Extract + 1% Penicillin/streptomycin (Penstrep) onto 1:100 Matrigel Reduced Factor (BD) in IMDM-coated fluorodishes. Differentiation was triggered by medium switch in IMDM + 2% horse serum + 1% Penstrep, and 24 h later, a thick layer of matrigel (1:2 in IMDM) was added. Myotubes were treated with 80 μg/ml of agrin and kept in 37°C/5%CO2(Falcone et al., 2014). Due to the difficulty of sexing mouse pups visually, sex of primary myoblasts and isolated myofibers, derived from 5-7 or 0 day old pups respectively, was not determined.

Method Details

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry: Rabbit anti-α-smooth muscle actin, mouse anti-Desmin, rabbit anti-Fibronectin, goat anti-CD31, mouse anti-MAP2, rabbit anti-Triadin antibody was a kind gift from Isabelle Marty, mouse anti-MyoD, rabbit anti-BrdU, mouse anti- Integrin α5 (clone SNAKA51), rat anti- Integrin β1 (clone 9EG7), goat anti- Tensin. Details of secondary antibodies are in the Key Resources Table.

siRNA/cDNA Transfection

Cells were transfected with siRNA (20nM) using RNAiMAX and cDNA (1μg/μl) using Lipofectamine 3000. To transfect, a mix containing siRNA (20nM) with 1μl RNAiMAX or cDNA (1μg/μl) with 1μl of Lipofectamine 3000 and reagent in 50μl of Opti-MEM was added to each fluorodish for 30 minutes followed by 1 wash with IMDM + 2% horse serum + 1% Penstrep and medium switch in the same medium to trigger differentiation. Co-transfections of plasmids and siRNAs were done using Lipofectamine 3000 using the same protocol. Primary myoblasts were transfected 6 h prior to differentiation in order to promote protein silencing or overexpression effectiveness from the beginning of differentiation. The following siRNAs were used: Scrambled siRNA, Itga5 siRNA#1, Itga5 siRNA#2, Fn1 siRNA#1 and Fn1 siRNA#2. The following plasmids were used: GFP-fibronectin, ChR2-GFP and GCaMP6f.

Drug Assays

When indicated, cells were treated with Mitomycin (Mitomycin C, 5ng/ml Sigma-Aldrich) 2 hours prior to differentiation. Fibronectin (1, 5 and 10μg/ml Sigma-Aldrich), Laminin (10μg/ml Sigma-Aldrich), Collagen (10μg/ml Ibidi) and Cilengitide (10μM Sigma-Aldrich) were added 1 day before myonuclei start positioning at the periphery. ML141 (Cdc42 inhibitor, 10 μM, Sigma-Aldrich), Rac1 inhibitor (10 μM, Merck Millipore), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor, 5 μM, Merck Millipore), FAK inhibitor (1 μM, Sigma-Aldrich) and Src inhibitor,PPi (10 μM, Merck Millipore) were added 1 day before myonuclei start positioning at the periphery of myofibers.

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultures at day two of differentiation using RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA yield and purity was assessed using Nanodrop 2000 apparatus. cDNA was synthesized using the High capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems) following manufacturer instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR MasterMix (Alfagene) and primers forward and reverse (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:200 from the initial concentration of 100mM. A mix containing 1 μl primer mix, 4 μl of cDNA and 5 μl SYBR Green was added to each well. Amplification of the Itga5 mRNA, encoding α5-integrin was achieved using the following primers: Forward primer; 5’-AAAGGACCCACAGAATGACCC-3’, Reverse primer; 5’-CCAAAATCTGAGCGGCAAGG-3’. Fn1 mRNA, encoding fibronectin was amplified using the following primers: Forward primer; 5’-TGACTGGCCTTACCAGAGGG-3’, Reverse primer; 5’-CATCTGTAGGCTGGTTCAGGC-3’. As a control, housekeeping gene mRNA hprt was amplified using the following primers: Forward primer; 5’-GTTAAGCAGTACAGCCCCAAA-3’, Reverse primer; 5’-AGGGCATATCCAACAACAAACTT-3’. qPCRs were performed three times and relative transcription levels were determined using the ΔΔct method.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

Fluorodishes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with triton X-100 (0.5% in PBS) at room temperature and washed 3 times with PBS. Cells were blocked with BSA 1% and goat serum 10% for 30 min at room temperature and primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C in saponin 0.1% and BSA 1% in PBS. Fluorodishes or isolated fibers were washed 3 times and then incubated with secondary antibodies together with Phalloidin and DAPI for 60 minutes at room temperature and then mounted in Fluoromount G. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times.

In Vitro Myofibers Obtained from Satellite Cells

Satellite cells were isolated from Pax7-nGFP mice (Sambasivan et al., 2009)using the previously described protocol (Falcone et al., 2014). Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed in a FACSAria III based on GFP fluorescence, with the sorted cell population presenting an average purity of 96,6%. GFP positive cells were plated in 8 well dishes and fibronectin (5μg/ml Sigma-Aldrich) was added 1 day before myonuclei start positioning at the periphery. Immunofluorescence and peripheral nuclei quantification were performed as described.

Proliferative Cell Labelling and Quantification

Cells were incubated with a 10 μM BrdU labeling solution (abcam) for a duration of 4h at 37°C, 1 day after treatment with mitomycin. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS,fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with triton X-100 (0.5% in PBS) for 20 min and treated with a 4N HCl solution for 20 min. Cells were washed with a Tris 100mM pH=8 solution and the immunofluorescence was performed as indicated above in “Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry”.

Cells were stained for MyoD and BrdU. Images were then acquired at different areas covering a total of ¼ of the surface of the fluorodish and stitched together using Zen software (Zeiss). Cells were then counted based on their staining and averaged per experiment.

Isolation of Myofibers

TA single fibers were isolated as described (Falcone et al., 2014). TA muscle was explanted from newborn male or female CD1 mice and then digested in DMEM containing 0.2% type I collagenase (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C. Mechanical dissociation of fibers was performed using a thin pasteur pipette and followed under a transilluminating-fluorescent stereomicroscope.

Muscle Clearing and Immunofluorescence

Whole muscles were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 8h, permeabilized with pre-treatment solution (1% triton X-100; 0,5% Tween; 0,25% Nonidet P-40, euromedex; 0,25% sodium deoxycholate, Sigma; 3% BSA; 0,02% sodium azide and 1% urea, Sigma, in PBS) overnight and blocked with CBB (Cláudio’s blocking buffer, 1% FBS, 3% BSA, 0,5% triton X-100, 0,01% sodium deoxycholate and 0,02% sodium azide in PBS) for 8h, with the blocking solution being changed every 2 hours. Primary antibodies were incubated for 3 days at 4°C while shaking. Whole muscles were then washed with PBS for 8 hours, changing PBS every 2 hours, and incubated in secondary antibodies together with DAPI for 3 days. The immunostaining was fixed with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0,25% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences). After immunostaining, whole muscles were placed in a 25%Formamide/10% Polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution for 8h followed by immersion in a 50%Formamide/20%PEG overnight. Clearing solutions were prepared according to the described protocol (Kuwajima et al., 2013). Briefly, 50%Formamide/20%PEG solution was made by mixing formamide 100% with a 40%PEG/H2O mixture (wt/vol) at a ratio of 1:1 (vol/vol). The 25%Formamide/10%PEG solution was made by mixing formamide 50% with a 20%PEG/H2O mixture (wt/vol) at a ratio of 1:1 (vol/vol). The 50% formamide solution was made by stirring formamide 100% in H2O. The PEG 40% solution was made by stirring PEG 8000 MW in warm H2O for 30 minutes.

Microscopy

Live imaging was performed using an incubator to maintain cultures at 37°C and 5% CO2 (Okolab) and × 20 0.3 NA PL Fluo dry objective. Epi-fluorescence images were acquired using a Nikon Ti microscope equipped with a CoolSNAP HQ2 camera (Roper Scientific), an XY-motorized stage (Nikon), driven by Metamorph (Molecular Devices). Confocal images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 and Zeiss LSM 880 with a 63x 1.4 NA Plan-Apochromat objective, driven by ZEN 2012 or 2.1 (black) software, respectively. 3D-time-lapse spinning disk microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Cell Observer Spinning Disk system equipped with Z-piezo (Prior), Spinning Disk CSU-X1M 5000 (Yokogawa), 488nm 561nm and 638nm excitation laser, an incubator to maintain cultures at 37°C and 5% CO2 (Pekon), EM-CCD camera Evolve 512 (Photometrics), a 63x 1.4 NA Plan-Apochromat objective, driven by ZEN software. Fiji was used as an imaging processing software and Adobe illustrator was used to raise figures.

Fatigue Experiments

Myofibers were transfected with the rhodopsin channel GFP-ChR2 and treated with vehicle, mitomycin or ML141 or knocked down for α5-integrin. Myofibers were then exposed to blue light and time was monitored until myofibers lost the ability to contract.

Calcium Measurements

Myofibers were transfected with the rhodopsin channel GFP-ChR2 and GCaMP6f and were live imaged at day 5 every 10ms with maximal blue light exposure. Reaching maximal calcium intensity occurred in 90 ms in all conditions. As such, the relative intensity was measurement in a ROI at 10 ms intervals.

Coated Bead Experiments

500 μl of 10% polystyrene beads (total of 5x107 beads; Phosphorex) were collected in an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged (6000 rpm, 3-5 min) to discard the supernatant. Beads were then washed 3 times in cold PBS and incubated to rock with 50 mg/ml fibronectin or BSA in cold PBS at 4°C overnight. The following day, beads were collected by centrifugation (6000 rpm, 3-5 min), supernatant discarded and beads were incubated in 10mg/ml BSA (1ml) at 4°C for 3 hours while rocking. Beads were then washed 3 times in cold PBS and ressuspended in 1.5 ml PBS, aliquoted and stored at -20°C. 60 000 Beads were then added to matrigel before differentiation of myofibers.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Peripheral Nuclei Position Quantification

Quantification was performed as previously described (Falcone et al., 2014). Myofibers were stained for DAPI, F-actin and triads and images in Z-stacks with 0.5 μm interval were acquired with a Zeiss Cell Observer spinning disk microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective. Nuclei extruding the myofiber periphery were scored as peripheral. In coated beads experiment only nuclei in close vicinity of beads were quantified.

Transversal Triad Quantification

Quantification was performed as previously described (Falcone et al., 2014). Myofibers were stained for DHPR1, triadin and DAPI and images in Z-stacks with 0.5 mm interval were acquired with a Zeiss Cell Observer spinning disk microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective. Myofibers having more than 50% of triads organized, where DHPR and Triadin were transversally overlapping, were scored as positive.

Desmin Quantification

Myofibers were stained for desmin and DAPI and images in Z-stacks with 0.5 μm interval were acquired with a Zeiss Cell Observer spinning disk microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective. Myofibers having more than 70% of desmin transversally organized at the Z-lines were scored as positive.

Non-muscle Cell Quantification

Cultures were fixed from day 1 to day 6 and stained for α-smooth muscle actin, F-actin and desmin. Images were then acquired at different areas covering a total of ¼ of the surface of the fluorodish and stitched together using Zen software (Zeiss). Cells were then counted based on their staining and averaged per day and experiment.

Cell-Cell Interaction Quantification

Transmitted live imaging of cultures (day 1 – 6) were collected with images every 30 min (the minimum interaction time observed in trial experiments using images acquired every 5 min). Number of interactions of non-muscle cells with myotubes and myofibers was counted whenever the plasma membrane of myotubes or myofibers was deformed by a non-muscle cell. This was performed for each frame and averaged across positions and experiments over 6 days.

Statistics and Reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed with Graphpad Prism (version 5.0 of GraphPad Software Inc.). Pair wise comparisons were made with Student’s t-test. In peripheral nuclei positioning analysis and in fiber thickness analysis in myofibers, Student’s t-tests were performed between scramble siRNA and experimental condition. The distribution of data points is expressed as mean ± SEM from three or more independent experiments. For statistics with an n lower than 10, a statistical power test was performed using GPower 3.1 based on the statistical test used. Outliers were detected using Gribbs’ test at a P value < 0.05. Variability arises in the maturity obtained from the in vitro muscle system obtained from primary myoblasts. As such, a minimum of 55% of peripheral nuclei in the control cohorts were required to consider the experiment. Representative images are from at least 3 experiments.

Data and Software Availability

Source data for figure panels Figures 1B, 1D, 1F, 2B, 2D, 3C, 3E, 3F, 3H, 4A, 4C, 4E, 4F as well as supplementary figure panels Figures S1A, S1D, S2A, S2B, S2D, S2F, S2G, S3B, S3D, and S3E are available in Table S3 (https://doi.org/10.17632/trhmpz9h23.1). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Gomes Laboratory for discussions, Isabelle Marty for the triadin antibody and the histology facility, and the bio-imaging team at the Instituto de Medicina Molecular (iMM). This work was supported by the European Research Council (E.R.G.), EMBO installation (E.R.G.), AIM France (W.R., E.R.G.), LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-007391, project co-funded by FEDER, through POR Lisboa 2020 – Programa Operacional Regional de Lisboa, PORTUGAL 2020, and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Author Contributions

W.R. and J.P.M. carried out experiments and analyzed data; W.R., J.P.M., and E.R.G. conceived and designed experiments; W.R. and E.R.G. wrote the manuscript with assistance from J.P.M.; all authors participated in the critical review and revision of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Published: June 21, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2018.05.031.

Contributor Information

William Roman, Email: william.roman@medicina.ulisboa.pt.

Edgar R. Gomes, Email: edgargomes@medicina.ulisboa.pt.

Supplemental Information

References

- Bruusgaard J.C., Liestøl K., Gundersen K. Distribution of myonuclei and microtubules in live muscle fibers of young, middle-aged, and old mice. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2006;100:2024–2030. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00913.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadot B., Gache V., Gomes E.R. Moving and positioning the nucleus in skeletal muscle – one step at a time. Nucleus. 2015;6:01–09. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2015.1090073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell I.D., Humphries M.J. Integrin structure, activation, and interactions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a004994. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Pankov R., Travis M.A., Askari J.A., Mould A.P., Craig S.E., Newham P., Yamada K.M., Humphries M.J. A specific α5β1-integrin conformation promotes directional integrin translocation and fibronectin matrix formation. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:291–300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S.T., Maxwell A.L., Kizana E., Ghoddusi M., Hardeman E.C., Alexander I.E., Allen D.G., North K.N. C2C12 Co-culture on a fibroblast substratum enables sustained survival of contractile, highly differentiated myotubes with peripheral nuclei and adult fast myosin expression. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:200–211. doi: 10.1002/cm.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-W., Wardill T.J., Sun Y., Pulver S.R., Renninger S.L., Baohan A., Schreiter E.R., Kerr R.A., Orger M.B., Jayaraman V. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro M., Hnia K., Gache V., Koch C., Gavriilidis C., Rodriguez D., Nicot A.-S., Romero N.B., Schwab Y., Gomes E. Amphiphysin 2 orchestrates nucleus positioning and shape by linking the nuclear envelope to the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. Dev. Cell. 2015;35:186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daramola O.A., Heyderman R.S., Klein N.J., Shennan G.I., Levin M. Detection of fibronectin expression by human endothelial cells using a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): enzymatic degradation by activated plasminogen. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;202:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander L.L., Rubin L.L. Acetylcholine receptor clustering and nuclear movement in muscle fibers in culture. J. Cell Biol. 1987;104:87–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42—the centre of polarity. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1291–1300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A. Integrin-mediated activation of Cdc42 controls cell polarity in migrating astrocytes through PKC$∖zeta$ Cell. 2001;106:489–498. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyden B. The myofibroblast: phenotypic characterization as a prerequisite to understanding its functions in translational medicine. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008;12:22–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone G., Boettiger D., Alemà S., Tatò F. Role of cell division in differentiation of myoblasts infected with a temperature-sensitive mutant of Rous sarcoma virus. EMBO J. 1984;3:1327–1331. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone S., Roman W., Hnia K., Gache V., Didier N., Lainé J., Auradé F., Marty I., Nishino I., Charlet-Berguerand N. N-WASP is required for Amphiphysin-2/BIN1-dependent nuclear positioning and triad organization in skeletal muscle and is involved in the pathophysiology of centronuclear myopathy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014;6:1455–1475. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gache V., Gomes E.R., Cadot B. Microtubule motors involved in nuclear movement during skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:865–874. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-06-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Dickerson J.B., Guo F., Zheng J., Zheng Y. Rational design and characterization of a Rac GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7618–7623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307512101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel P., Lee Y.L., Sobota R.M., Calvi A., Koullourou V., Patel R., Mamchaoui K., Nédélec F., Shackleton S., Schmoranzer J. Nesprin-1α-dependent microtubule nucleation from the nuclear envelope via Akap450 is necessary for nuclear positioning in muscle cells. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:2999–3009. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes E.R., Jani S., Gundersen G.G. Nuclear movement regulated by Cdc42, MRCK, myosin, and actin flow establishes MTOC polarization in migrating cells. Cell. 2005;121:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody M.F., Sher R.B., Henry C.A. Hanging on for the ride: adhesion to the extracellular matrix mediates cellular responses in skeletal muscle morphogenesis and disease. Dev. Biol. 2015;401:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati A.K. Basement membrane component changes in skeletal muscle transplants undergoing regeneration or rejection. J. Cell. Biochem. 1985;27:337–346. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240270404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen G.G., Worman H.J. Nuclear positioning. Cell. 2013;152:1376–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke J.H., Gardner J.P., Dow R.L., Changelian P.S., Brissette W.H., Weringer E.J., Pollok B.A., Connelly P.A. Discovery of a novel, potent, and src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor Study of Lck- and FynT-Dependent T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A.J., Duxson M.J., Fitzsimons R.B., Rieger F. Myonuclear birthdates distinguish the origins of primary and secondary myotubes in embryonic mammalian skeletal muscles. Development. 1989;107:771–784. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman S.J., Ridley A.J. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huveneers S., Danen E.H.J. Adhesion signaling—crosstalk between integrins, Src and Rho. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1059–1069. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima T., Sitko A.A., Bhansali P., Jurgens C., Guido W., Mason C. ClearT: a detergent- and solvent-free clearing method for neuronal and non-neuronal tissue. Development. 2013;140:1364–1368. doi: 10.1242/dev.091844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagana A., Goetz J.G., Cheung P., Raz A., Dennis J.W., Nabi I.R. Galectin binding to Mgat5-modified N-glycans regulates fibronectin matrix remodeling in tumor cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:3181–3193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3181-3193.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Jenkins N.A., Copeland N.G. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 2003;13:476–484. doi: 10.1101/gr.749203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukjanenko L., Jung M.J., Hegde N., Perruisseau-Carrier C., Migliavacca E., Rozo M., Karaz S., Jacot G., Schmidt M., Li L. Loss of fibronectin from the aged stem cell niche affects the regenerative capacity of skeletal muscle in mice. Nat. Med. 2016;22:897–905. doi: 10.1038/nm.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton G.W.G., Gomes E.R., Folker E.S., Vintinner E., Gundersen G.G. Linear arrays of nuclear envelope proteins harness retrograde actin flow for nuclear movement. Science. 2010;329:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1189072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger T., Gache V., Xu M., Cadot B., Folker E.S., Richardson B.E., Gomes E.R., Baylies M.K. MAP and kinesin-dependent nuclear positioning is required for skeletal muscle function. Nature. 2012;484:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M.M., Lawson J.A., Mathew S.J., Hutcheson D.A., Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3625–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmani N., Vitale N., Borg J.-P., Etienne-Manneville S. Scrib controls Cdc42 localization and activity to promote cell polarization during astrocyte migration. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:2395–2405. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajcini K., Pomerantz J., Alkan O., Doyonnas R., Blau H. Myoblasts and macrophages share molecular components that contribute to cell-cell fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:1005–1019. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M.R., Falcone S., Cadot B., Gomes E.R. In vitro differentiation of mature myofibers for live imaging. J. Vis. Exp. 2017 doi: 10.3791/55141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston E., Lu Z., Biscocho N., Soumaka E., Mavroidis M., Prats C., Lømo T., Capetanaki Y., Ploug T. Blood vessels and desmin control the positioning of nuclei in skeletal muscle fibers. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;209:874–882. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A.J., Hodge R.G. Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:496. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R., Ma L., Miki H., Lopez M., Kirchhausen T., Takenawa T., Kirschner M.W. The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42-dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell. 1999;97:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman W., Martins J.P., Carvalho F.A., Voituriez R., Abella J.V.G., Santos N.C., Cadot B., Way M., Gomes E.R. Myofibril contraction and crosslinking drive nuclear movement to the periphery of skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:1189–1201. doi: 10.1038/ncb3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan R., Gayraud-Morel B., Dumas G., Cimper C., Paisant S., Kelly R.G., Kelly R., Tajbakhsh S. Distinct regulatory cascades govern extraocular and pharyngeal arch muscle progenitor cell fates. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes J.R. The basement membrane/basal lamina of skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:12601–12604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes J.R., Lichtman J.W. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:791–805. doi: 10.1038/35097557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack-Davis J.K., Martin K.H., Tilghman R.W., Iwanicki M., Ung E.J., Autry C., Luzzio M.J., Cooper B., Kath J.C., Roberts W.G. Cellular characterization of a novel focal adhesion kinase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:14845–14852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surviladze Z., Waller A., Strouse J.J., Bologa C., Ursu O., Salas V., Parkinson J.F., Phillips G.K., Romero E., Wandinger-Ness A. Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2010. A potent and selective inhibitor of Cdc42 GTPase. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna D., Disatnik M.-H., Rayburn H., Bronson R.T., Yang J., Rando T.A., Hynes R.O. Dystrophic muscle in mice chimeric for expression of α5 integrin. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:849–859. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torr E.E., Ngam C.R., Bernau K., Tomasini-Johansson B., Acton B., Sandbo N. Myofibroblasts exhibit enhanced fibronectin assembly that is intrinsic to their contractile phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:6951–6961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.606186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehata M., Ishizaki T., Satoh H., Ono T., Kawahara T., Morishita T., Tamakawa H., Yamagami K., Inui J., Maekawa M. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–994. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K.I., Katsuta S., Soya H. Natural occurrence of myofiber cytoplasmic enlargement accompanied by decrease in myonuclear number. Jpn. J. Physiol. 2003;53:145–150. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.53.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Wang L.-P., Brauner M., Liewald J.F., Kay K., Watzke N., Wood P.G., Bamberg E., Nagel G., Gottschalk A. Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature. 2007;446:633–639. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.