Abstract

Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) is a highly conserved enzyme that is crucial for glycolysis. PGK is a monomeric protein composed of two similar domains and has been the focus of many studies for investigating interdomain interactions within the native state and during folding. Previous studies used traditional biophysical methods (such as circular dichroism, tryptophan fluorescence, and NMR) to measure signals over a large ensemble of molecules, which made it difficult to observe transient changes in stability or structure during unfolding and refolding of single molecules. Here, we unfold single molecules of PGK using atomic force spectroscopy and steered molecular dynamic computer simulations to examine the conformational dynamics of PGK during its unfolding process. Our results show that after the initial forced separation of its domains, yeast PGK (yPGK) does not follow a single mechanical unfolding pathway; instead, it stochastically follows two distinct pathways: unfolding from the N-terminal domain or unfolding from the C-terminal domain. The truncated yPGK N-terminal domain unfolds via a transient intermediate, whereas the structurally similar isolated C-terminal domain has no detectable intermediates throughout its mechanical unfolding process. The N-terminal domain in the full-length yPGK displays a strong unfolding intermediate 13% of the time, whereas the truncated domain (yPGKNT) transitions through the intermediate 81% of the time. This effect indicates that the mechanical properties of yPGK cannot be simply deduced from the mechanical properties of its constituents. We also find that Escherichia coli PGK is significantly less mechanically stable as compared to yPGK, contrary to bulk unfolding measurements. Our results support the growing body of observations that the folding behavior of multidomain proteins is difficult to predict based solely on the studies of isolated domains.

Introduction

The understanding of protein folding has flourished with both experimental (1, 2) and theoretical investigation of small proteins (3, 4, 5). The vast majority of these studies investigate single-domain proteins, even though less than 35% of cellular eukaryotic proteins have only a single domain (6, 7). In contrast to small, single-domain proteins, large, multidomain proteins frequently display complex folding pathways and stable intermediates under quasi-equilibrium conditions (8, 9). Although in some cases the overall properties of the wild-type multidomain protein can be inferred from the sum of the properties of its individual domains (10, 11), the domain-domain interactions often affect protein stability, protein-folding kinetics, or protein misfolding (12, 13, 14, 15). In these cases, the overall behavior of the wild-type multidomain protein cannot be predicted from its isolated domains, and standard theories for single-domain proteins often do not apply (16, 17, 18, 19, 20). Multidomain proteins frequently manifest misfolding and aggregation in non-native states (21, 22, 23), which makes folding studies very difficult under in vitro conditions using bulk methods. Single-molecule methods are often advantageous because they minimize opportunities for proteins to aggregate during unfolding measurements of individual molecules. Thus, single-molecule experiments (such as single-molecule force spectroscopy, reviewed in (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30)) combined with computer simulations (such as molecular dynamics (MD)) have become excellent tools to precisely characterize the unfolding pathways of complex multidomain proteins (31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43).

Single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) can also measure the mechanical stability of small and large proteins in addition to measuring the unfolding and refolding pathways. The magnitude of the unfolding force for unraveling individual domains is of particular importance when studying proteins with obvious mechanical functions such as muscle proteins (titin (11, 44, 45, 46, 47), myosin (48, 49)), cytoskeletal proteins (spectrin (50, 51, 52), ankyrin (33, 34, 35, 36, 53)), membrane proteins involved in cell adhesion such as cadherins (54, 55), or extracellular matrix proteins such as fibronectin (56, 57) and tenascin (58). More generally, the mechanical stability (as measured by the magnitude of the mechanical unfolding force) of many proteins, even those with no obvious mechanical function, is critical to their ability to be transported across cellular membranes or to their processing by the chaperones (59) and proteases (60).

One of the simplest SMFS methods is atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based SMFS, also known as atomic force spectroscopy (AFS). This technique has already proven very useful in examining proteins’ unfolding and refolding pathways and capturing important details such as transient unfolding intermediates (61) while minimizing protein aggregation (31), making it an ideal tool for studying the mechanical stability and unfolding-refolding behavior of multidomain proteins. Recent improvements by the Perkins group in AFS force resolution and stability and the development of new powerful assays for specific attachment of molecules have significantly increased the AFS success rate, making AFS also ideally suited for studying mechanically weak and fast folding proteins (62, 63). Here, we combine AFS with coarse-grained steered MD simulations to examine the mechanical stability and the (un)folding mechanism of a model multidomain protein—yeast phosphoglycerate kinase (yPGK) (64).

The protein yPGK has two structurally homologous domains connected by an α-helix (65), as shown in Fig. 1 A. The N-terminal domain of yPGK contains the first 185 residues, and the C-terminal domain is composed of the last 230 residues; both are in Rossmann fold topology (66, 67, 68, 69, 70) and are considered stable in isolation (68, 69). yPGK and its two isolated domains have been studied using traditional biochemical methods—including heat and cold denaturation (18, 64, 69, 71, 72, 73), chemical denaturation (74, 75, 76, 77), and high-pressure denaturation (78)—and the unfolding and refolding processes have been investigated by several techniques, including circular dichroism (69, 79), tryptophan fluorescence (70, 80), stop-flow fluorescence (20, 81), NMR (82, 83), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (84), and more recently fast relaxation imaging (85, 86, 87, 88). Although these previous studies have suggested that the unfolding and folding dynamics of yPGK as a whole cannot be explained simply by the unfolding and folding dynamics of the individual domains, the origin of this complexity has remained unclear. We now attempt to answer the open question of how the structural subunits in yPGK interact and contribute to the overall mechanical stability and folding of yPGK by combining AFS experiments and MD simulations to compare the characteristics of individual domains with the whole protein.

Figure 1.

(A) Cartoon structure of yPGK colored from N-terminus (red) to C-terminus (blue) (65). (B) A schematic of the AFS unfolding experiment of yPGK flanked by three I91 domains on the C-terminus and two I91 domains on the N-terminus is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Materials and Methods

Protein engineering

The DNA for yPGK (65, 89) was cloned from a single yeast colony (Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain S288c) using colony polymerase chain reaction and verified by Sanger sequencing. The polymerase chain reaction product was cut at the BssHII and NheI restriction sites and ligated into the third and fourth modules in poly(I91) (90, 91) (formerly known as I27 (46)) pRsetA vector (a kind gift from Clarke (92)). The eighth module of the gene was replaced with a Strep-tag. Truncated yPGK N-terminal domain (yPGKNT) and truncated C-terminal domain (yPGKCT) (68, 69, 70) genes were generated from site-directed mutagenesis and reinserted into the poly(I91) pRsetA vector by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) in the same place as yPGK. All proteins were flanked by two I91 domains on the N-terminal side and three I91 domains on the C-terminal side to facilitate their attachment to the substrate and pickup by the AFM tip. These flanking I91 domains also allow unequivocal identification of single-molecule recordings that contain unfolding of the complete protein of interest rather than its fragment (as long as at least four characteristic unfolding force peaks associated with unfolding of I91 domains are registered in the force-extension profile, we know, from the composition of our protein construct, that the complete protein of interest must have been captured, stretched, and unfolded) (29).

All engineered plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli C41(DE3) pLysS cells (Lucigen, Middleton, WI). A freshly grown bacterial colony was inoculated in a 15 mL Luria-Bertani broth medium with 1 mM ampicillin at 37°C for overnight growth. For preculture, the 15 mL culture were inoculated into 1 L Luria-Bertani broth medium with 1 mM ampicillin for 4 h at 37°C (until OD 600 > 0.8). After that, 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added, and the temperature was lowered down to room temperature for overnight expression. Cells were harvested the next day by spinning down at 4000 × g for 40 min and then frozen at −80°C for several hours. Thawed cells were suspended in lysis buffer containing lysozyme and benzonase (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The lysates were spun down at 13,100 × g for 30 min at 4°C, then the supernatants were run through a gravity flow Strep-Tactin sepharose column (IBA, Göttingen, Germany). Proteins were then exchanged into 1× phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) using Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter 50 kDa devices (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and stored at 4°C before use.

Atomic force spectroscopy

AFS measurements were obtained using a custom-built AFM instrument (33). Automation routines to control the AFM (93) were implemented in Labview 7.0 (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Cantilever spring constants were calibrated in the buffer solution using the energy equipartition theorem (94). All measurements were done at a constant velocity of 100 nm/s in a phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) solution at room temperature. In all experiments, the purified protein was diluted to 30 μg/mL, applied to recently evaporated gold, and incubated for half an hour. Measurements were performed using OBL10 cantilevers (Bruker, Camarillo, CA), which have a spring constant of 7 ± 3 pN/nm. A worm-like chain (WLC) model (95) with a persistence length of 0.6 nm was fit to each peak to measure contour-length increments (ΔLc) in the force extension (FE) data (96).

Coarse-grained simulation

Structure-based models were generated using the SMOG web server (97) from Protein Data Bank: 3PGK (65). In this coarse-grained model, each residue is modeled as a single pseudo-atom. Steered MD are conducted on this model, with intermolecular forces determined by a coarse-grained potential. This potential contains terms for bonds, angles, and improper angles, which have equilibrium values based on the initial structure. All residues identified as a contact have an attractive 12-6 Lennard-Jones potential, and residues identified as noncontacts have a repulsive component. More information about parameter values are described by Clementi et al. (98). Simulations were conducted using GROMACS 4.5.5 (99) by pulling from the N-terminus at a speed of 1 nm/ns and using a spring constant of 6 pN/nm. To choose a good temperature, we conducted a series of simulations under temperature values ranging from 130 to 145 K and found that T = 140 K gave simulated FE curves that agree well with the experimental results from both yPGKNT and yPGKCT. Other temperatures generate FE curves only matching one of the two constructs or having no resemblance to either construct. So, we finally chose T = 140 K and conducted more simulations under this temperature to ensure the reproducibility of the results.

Results and Discussion

yPGK mechanically unfolds in at least three intermediates

We first studied the unfolding pathway of the wild-type, full-length yPGK using AFS. The yPGK protein was flanked by I91 domains on both the N-terminus and C-terminus and pulled along the N-C coordinate at constant velocity (Materials and Methods; Fig. 1 B). Representative examples of yPGK unfolding FE curves are shown in Fig. 2 A, superimposed together. There are two prominent peaks in 100% of force curves, peak 1 and peak 2, whereas peak 0 at short extensions appears in 26% (n = 61) of the recordings. The probability density plots for both peak 1 and peak 2 are shown in Fig. 3 E.

Figure 2.

FE curves from the unfolding of I91-flanked full yPGK (A) and (B); yPGKNT (C); yPGKCT (D). To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 3.

(A–D) Distributions of contour-length increment (ΔLc) for full yPGK peak 1 (A) and peak 2 (B); yPGKNT (C); yPGKCT (D). (E) A probability density plot for full yPGK peak 1 (red), peak 2 (blue), yPGKNT (violet), and yPGKCT (green) is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

The ΔLc of peak 1 and peak 2 of yPGK do not match a single normal distribution. The majority of ΔLc histograms for peak 1 can be fit by a normal distribution with a mean ± SD of 53 ± 4nm (Fig. 3 A) but have a remnant that sits around 44 nm. The majority of ΔLc histograms for peak 2 can be fit by a normal distribution with mean ± SD of 47 ± 1 nm. However, there is also a long tail that expands between 51 and 56 nm (Fig. 3 B, p = 0.021, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality).

The ΔLc of peak 1 and peak 2 (53 and 47 nm respectively) are also shorter than the theoretical ΔLc predicted of both the N-terminal and C-terminal domain (67 and 84 nm, respectively, based on their respective numbers of amino acids), and thus assigning the unfolding of a particular domain to a peak in the FE curve based solely on ΔLc is not possible. This shorter-than-expected ΔLc suggests that only part of either domain can be the origin for peak 1 or peak 2. Because ΔLc information does not reveal the domain assignment for the force peaks, we will further attempt this assignment by examining the truncated domains and comparing their mechanical stabilities and unfolding pathways.

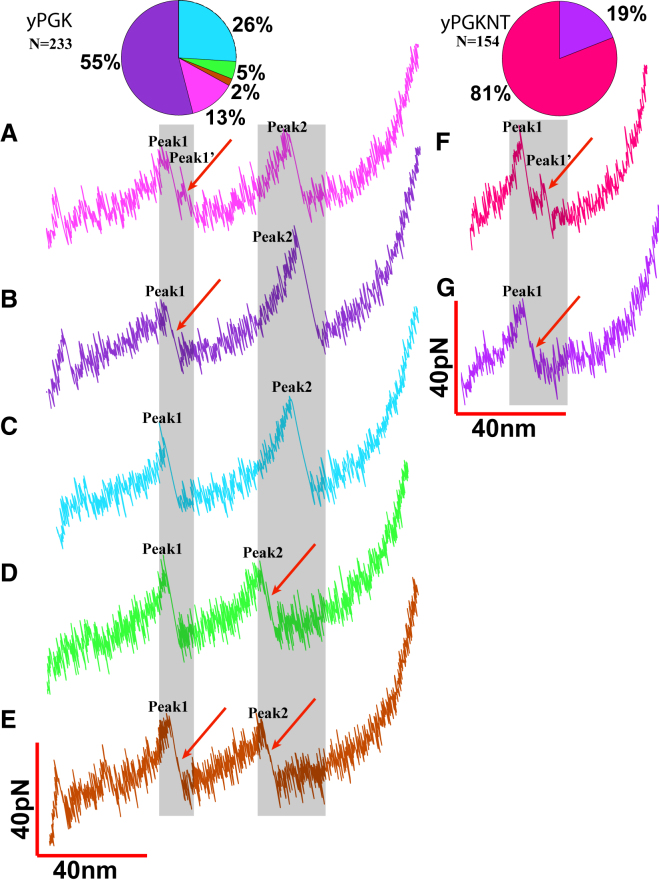

In addition to the three pervasive peaks for the full unfolding of the complete yPGK, we found several short-lived events in the unfolding pathway. We observed that 13% (n = 31) of the full-yPGK AFM pulling data have an additional peak 1′ that occurs immediately after peak 1 at a lower force (Figs. 2 B and 4 A). Additionally, we observe that 55% (n = 126) of the recordings display a small force event visible on the shaded region between the rupture point of peak 1 and the rest of the FE curve on the otherwise smooth part of the curve, which normally only captures the relaxation of the AFM cantilever after the major unfolding event when it increases the length of the molecule (Fig. 4 B). We interpret this small event as a transient unfolding intermediate (100). Only 5% (n = 12) of the recordings show a similar transient unfolding intermediate on the shaded region between the rupture point of peak 2 and the rest of the FE curve (Fig. 4 D). We observed that 2% (n = 5) of recordings show intermediates on the shaded region between the rupture point of both peak 1 and peak 2 and the rest of the FE curve (Fig. 4 E). Peak 1′ and the transient intermediates may be informative for determining the force-peak assignments to domains, if the truncated yPGK domains also display similar unfolding intermediates upon stretching by AFM.

Figure 4.

The pie chart shows the relative frequency of intermediates (A and C) and the corresponding FE curves (B and D) are shown for the unfolding of I91-flanked full yPGK (left) and 1;1yPGKNT (right). The shaded areas highlight the region between the rupture point of corresponding force peaks and the rest of the FE curves, and red arrows point at additional peaks or transient intermediates. To see this figure in color, go online.

The truncated N-terminal domain of yPGK mechanically unfolds via transient intermediates

We also studied the truncated N-terminal and truncated C-terminal domains to understand how they may contribute to the complete unfolding of yPGK. We first created a construct containing the truncated N-terminal domain flanked by I91 domains (yPGKNT) and probed the mechanical stability and unfolding pathway using SMFS as before (Materials and Methods).

The histogram of ΔLc (n = 155 total recordings) of yPGKNT can be fit by a single normal distribution (Fig. 3 C) with a mean ± SD of 55 ± 2 nm (p = 0.994, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality)). We also observe transient events, similar to peak 1 in full yPGK: 81% (n = 126 total number of recordings) of recordings have a small force peak rising right after the first unfolding peak (Figs. 2 C and 4 F), and a transient intermediate appeared on the shaded region between the rupture point of the first unfolding peak and the rest of the FE curve in the remaining 19% (n = 29) of recordings (Fig. 4 G). We did an analysis of the intermediates of yPGK and yPGKNT to determine whether their lifetimes are similar, which could allow a better comparison with the relative occurrences. We followed established methods (101, 102, 103) for extracting the force-dependent unfolding rate and found that they showed no significant differences (Fig. S2). Therefore, we hypothesize that the difference in relative occurrence is a result of the difference in unfolding pathway caused by the lack of the tandem C-terminal domain.

We used steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations to provide detailed structural changes that might give rise to the unfolding force peaks (104). SMD results show agreement with the experimental FE recordings of yPGKNT (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that the first (major) force peak arises when residues 166–185 detach from the rest of yPGKNT, followed by the gradual extension of residues 130–166 (Fig. 5, second and third bottom panels), and the second (minor) force peak appears at the time that residues 15–130 unfold (Fig. 5, fourth and fifth bottom panels). Residues 1–15 (beginning of the N-terminal domain) gradually extended before the first force peak (Fig. 5, first and second bottom panels). We find that the simulated ΔLc for peak 1 in the yPGKNT FE curve should be (185 − 130) × 0.365 nm/residue (105) − 3.8 nm = 16.3 nm, which matches the AFM-measured 14.0 nm. Fig. 5 C, magenta distribution, and the simulated ΔLc for peak 1′ should be (130 − 15) × 0.365 nm/residue − 4.6 nm = 37.4 nm, very close to the experimentally measured 40.5 nm (Fig. 5 C, dark purple distribution).

Figure 5.

Superposition of unfolding traces of yPGKNT. (A) Unfolding traces determined by experimental AFM measurements are shown. The dashed lines are WLC fits with a persistence length of 0.6 nm. Horizontal scale bars, 20 nm extension; vertical scale bars, 20 pN force. (B) Unfolding traces determined by simulated SMD from coarse-grained models of the structure are shown (see details under Materials and Methods). The bottom panels show the detailed structural conformation at each stage marked in (B). All atom structural models were reconstructed from coarse-grained backbone Cα structures in the simulated trajectory by the program PULCHRA (121). (C) ΔLc for peak 1 (magenta) and peak 1′ (dark purple) in yPGKNT unfolding data are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

The C-terminal domain of yPGK has higher mechanical stability than the N-terminal domain

The C-terminal domain of yPGK is structurally similar to the N-terminal domain in that it also has a core of six parallel β-strands packed by α-helices. Because of the similarity, we hypothesized that the truncated C-terminal domain would also show a similar transient unfolding intermediate when stretched by AFM. An I91-flanked truncated C-terminal domain (yPGKCT) was used for pulling, and representative FE curves of yPGKCT are shown in Fig. 2 D.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the unfolding of yPGKCT shows a single force peak with no transient unfolding intermediate. The yPGKCT ΔLc distribution (Figs. 3 D and 6 C) can be fit with a single normal distribution with mean and SD of 47 ± 2 nm (p = 0.746, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality), which is shorter than the calculated ΔLc of the yPGKCT, indicating that only part of the C-terminal domain is contributing to the ΔLc of the peak.

Figure 6.

Superposition of unfolding traces of yPGKCT. (A) Unfolding traces determined by experimental AFM measurements are shown. The dashed lines are WLC fits with a persistence length of 0.6 nm. Horizontal scale bars, 20 nm extension; vertical scale bars, 20 pN force. (B) Unfolding traces determined by simulated SMD from coarse-grained models of the structure are shown (see details under Materials and Methods). The bottom panels show the detailed structural conformation at each stage marked in (B). All atom structural models were reconstructed from coarse-grained backbone Cα structures in the simulated trajectory by the program PULCHRA (121). (C) ΔLc distributions for peak 1 in yPGKCT unfolding data are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

As before, we conducted SMD simulations to determine which part of the structure produces the force peak. The simulation results for the mechanical unfolding of yPGKCT (Fig. 6) indicate that the undocking of residues 202–328 from the rest of yPGKCT creates the unfolding force peak (Fig. 6, second and third bottom panels). Before the force peak, residues 186–202 and residues 328–415 (both ends of the C-terminal domain) slowly unwind and produce a smooth curve that can be fit by a WLC model (Fig. 6, first and second bottom panels). Thus, the simulated ΔLc for yPGKCT force peak should be (328 − 202) × 0.365 nm/residue − 0.9 nm = 45.1 nm, which is close to the mean of the AFM data for peak 2 in the data of yPGKCT (Figs. 3 D and 6 C).

PGK unfolds from the N-terminal to the C-terminal domain

Comparing ΔLc distributions of yPGK, yPGKNT, and yPGKCT and the frequencies of transient intermediates appearing in the force peaks, we propose that peak 1 in full-length yPGK mainly comes from the unfolding of its N-terminal domain, whereas peak 2 mainly originates from the C-terminal domain unfolding. This claim is supported by our observation that yPGKNT has a similar ΔLc distribution as compared to peak 1 in full-length yPGK. Likewise, ΔLc distribution of yPGKCT and peak 2 in yPGK are similar. These similarities suggest that the origin of peak 1 is the unfolding of the N-terminal domain and the origin of peak 2 is the unfolding of the C-terminal domain.

A second proof of the argument comes from analyzing the transient intermediates in the unfolding pathway. In the mechanical unfolding of yPGK, we observe that a much larger portion of recordings show either an additional peak after peak 1 (13%, Fig. 4 A) or a weak transient intermediate on the shaded region between the rupture point of peak 1 and the rest of the FE curve (55%, Fig. 4 B) than the portion of recordings showing similar intermediates on peak 2 (5%, Fig. 4 D and left pie plot on top row). Thus, the fact that yPGKNT displays intermediates during its unfolding process while yPGKCT does not supports our hypothesis that the N-terminal domain unfolds before the C-terminal domain the majority of the time.

A third proof is from using an analysis of the possible structural rearrangements available to a specific set of ΔLc (106). Using this analysis (see Supporting Materials and Methods), we find that the most likely unfolding pattern involves unfolding from the middle of PGK, then unfolding the N-terminal domain, and then the C-terminal domain. This analysis also shows that a given recording may be assigned to swap the unfolding order of the N-terminal and C-terminal domain 20% of the time.

The occasional swapping of the unfolding order has been observed and described elsewhere (107, 108, 109). In our ΔLc distributions, we can also calculate the swapping probability from the overlap of the two distributions. We note that these distributions are rate dependent, but as long as the unfolding proceeds along a single pathway, we do not expect the broadness of the distribution to change dramatically at lower or higher speeds (110). We fitted distributions of peak 1 and peak 2 with a Gaussian mixture model with two components and found that the majority component for peak 1 is mean ± SD of 53 ± 3 nm and the majority component for peak 2 is 47 ± 2 nm. The crossing point between the two is ∼50 nm. In peak 1, then, there is a 21% chance that that it unfolds at a lower ΔLc (similar to peak 2), and in peak 2, there is a 22% chance that it unfolds with a higher ΔLc (similar to peak 1). These percentages are consistent with our hypothesis that peak 1 corresponds to the unfolding of the N-terminal domain and that peak 2 corresponds to the unfolding of the C-terminal domain.

Using force probes to determine structural transitions in the unfolding pathway of PGK

To further identify the positions of the points of mechanical resistance in yPGK, we used force probes that we recently developed while determining the mechanical unfolding pathway of a large ankyrin repeat protein (111). This assay involves the insertion (at the DNA level) of an antiparallel coiled-coil peptide (CC) into various regions of the host protein. This CC protein serves as a force probe that registers the position of the CC unfolding force peak in relation to the main unfolding force peak(s) of the host upon unfolding (111). A regular polyglycine or polythreonine loop becomes entropically costly as the number of residues increase and can destabilize the host protein when the loop is too large (112). The CC probe can circumvent this length limitation because its structure is stabilized by enthalpic interactions that keep the distance between the N- and C-termini very short, even for long CCs.

Similar to experiments on ankyrin repeats, we inserted the antiparallel CC probe into different loop regions in yPGK to minimize the effect on the native structure. To identify a position for the force probe, we sought loops in between α-helices that were far away from the interface to minimize disruption to the native state and also to prevent creating new domain-domain interactions. Specifically, we inserted the probe in the N-terminal domain between amino acids 67 and 68 for the first construct yPGK68CC (Fig. 7 A) and in the C-terminal domain between amino acids 254 and 255 for the second construct yPGK254CC (Fig. 7 B). We hypothesize that the CC probe only would affect the mechanical stability of the host domain but would not significantly affect the other domain. We inserted the genes of both constructs to replace the third and fourth modules in the poly(I91) pRsetA vector (92).

Figure 7.

Comparison of FE curves between (A) yPGK68CC (red) and (B) yPGK254CC (violet). Numbers denote the peak labels in the FE curves. (C) A superimposition of the FE curves from both constructs together on top of WT PGK (cyan) is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

We pulled on the two yPGK constructs with inserted force probes and observed reproducible force extension patterns from both. Superimposition of the FE curves from the two constructs together and on top of wild-type yPGK force curves (Fig. 7 C) demonstrates that both constructs are ∼27 nm longer in ΔLc before the first I91 module unfolds (which is the ΔLc of the CC probe) as compared with wild-type yPGK. This result confirms that both constructs are fully unfolded before the first I91 module starts to unfold, strongly suggesting that the CC inserts also unfold before any I91 module unfolds.

The insertion of the force probe in the N-terminal domain (yPGK68CC) shows two new additional peaks, peak 0′ and peak 0″ (Figs. 7 A and 8 A), both located between peak 0 and peak 1. The ΔLc histograms of both yPGK68CC peak 1 and peak 2 show two distributions, with a mean of 36 nm and a mean of 45 nm, respectively (Fig. 8, B and C). Based on our hypothesis that the CC probe should mainly affect the N-terminal domain for the yPGK68CC construct, we propose that the distribution with the mean of 45 nm mainly comes from the C-terminal domain, consistent with the ΔLc distribution of wild-type yPGK peak 2 shown in Fig. 3 B, whereas the ΔLc of N-terminal domain reduces to 36 nm as the effect of CC insertion. Because the magnitude of force of peak 1 is not significantly affected in yPGK68CC (Fig. 8 A), we propose that CC insertion destabilizes somewhat a portion of the N-terminal domain that is before the point of major mechanical resistance (along the sequence), causing this portion to unfold earlier, producing peaks 0′ and 0″. We note that according to the SMD simulation results, the ΔLc of the N-terminal domain should be produced by unfolding residues 15–185. Thus, in yPGK68CC, only residues 68–185 should contribute to the ΔLc of the N-terminal domain, which should give rise to a ΔLc of (185 − 68) × 0.365 nm/residue − 3.6 nm = 39.1 nm, which is close to the mean of the AFS-determined distribution. We observed no transient intermediates appearing in either peak 1 or peak 2 of yPGK68CC, suggesting that this intermediate may involve unfolding of the residues in the vicinity of the CC insertion site (residue 68). We also note that peak 1 and peak 2 in yPGK68CC, similar to wild-type yPGK, both have two distributions visible in ΔLc histograms, suggesting occasional swapping of the unfolding order. Interestingly, unfolding-order swapping seems to be more frequent in yPGK68CC as compared to wild-type yPGK.

Figure 8.

(A) Comparison of FE curves between WT PGK (cyan) and yPGK68CC (red). (B and C) ΔLc histograms of peak 1 in yPGK68CC (B), peak 2 in yPGK68CC (C), peak 1 in yPGK WT, and peak 2 in yPGK WT are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

The force curves of yPGK with the force probe inserted into the C-terminal domain (yPGK254CC) also show peak 0′ and peak 1″ in addition to peak 0, peak 1, and peak 2 in wild-type (WT) yPGK (Fig. 9). Interestingly, for this construct, in ∼50% of the SMFS recordings, peak 2 shows a transient unfolding intermediate, which indicates that peak 2 in yPGK254CC likely represents the unfolding of the N-terminal domain, opposite to what was observed for the WT protein (Fig. 9 B). Thus, the force probe inserted into the C-terminal domain causes the domain to be mechanically weakened and unfold earlier than the N-terminal domain, producing peak 1 and peak 1″.

Figure 9.

(A) Comparison of FE curves between WT PGK (cyan) and yPGK254CC (violet). (B) A representative recording that has observable unfolding intermediates (pointed out by red arrow) in peak 2 is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

The results from both constructs containing force probes support our original claim that these CC force probes should only affect the host domain without completely destroying their structure and with no (or minimal) effect on the neighboring domains. This observation further suggests that CC probes may indeed be useful in identification of the origin of force peaks in complex multidomain proteins. These results also suggest that CC probes can provide a unique means to modulate domains’ stability relative to one another and may be used to change (steer) the unfolding pathway by eliminating some unfolding intermediates, introducing new intermediates, or switching the unfolding order between the domains.

E. coli PGK displays lower mechanical stability than yeast PGK

The E. coli homolog of yeast PGK (ecPGK) contains 387 amino acids, compared to 415 residues of yPKG. The atomic structure of ecPGK (Protein Data Bank: 1ZMR) shows high similarity to that of yPGK. In chemical unfolding studies, Marqusee and co-workers found that the unfolding rate of ecPGK was much lower than that of yPGK, even though the free energy of unfolding of full yPGK and ecPGK were not significantly different. In addition, ecPGK was found to be resistant to protease thermolysin, whereas yPGK is not (113). This latter result suggests that ecPGK should be more rigid and potentially should require a greater force in mechanical unfolding measurements (at comparable stretching speeds) as compared to yPGK, even though generally thermodynamic and mechanical stabilities of the same protein do not need to correlate (114). Having those observations in mind, we performed SMFS measurements on ecPGK and compared the results with the results from yPGK.

The comparison between the mechanical stability of ecPGK and yPGK is shown in Figs. 10 and 11. There are three peaks that can be discerned when individual recordings from single I913-ecPGK-I913 protein molecules are superimposed on top of each other (Fig. 10 B). Contrary to our hypothesis, we find that ecPGK is mechanically weaker than yPGK, as is clearly shown in the probability density plot (Fig. 11). This observation will require further experiments involving varying the loading rate in SMFS measurements to determine not only the heights of the energy barriers for both proteins under mechanical conditions but also their shapes as determined by the position of the transition states with respect to the native state. Considering the results of the chemical denaturation study, one may anticipate that the transition states for yPGK are positioned much closer to the native state as compared to ecPGK and thus require greater unfolding forces, even though yPGK energy barriers could have lower heights compared to those of ecPGK. It is also tempting to speculate that the lower mechanical stability of ecPGK (which could not have been deduced based solely on bulk measurements) may have some biological relevance in that it would allow faster degradation of this protein by the proteases like Clp (60), which may be advantageous considering the shorter life cycle of E. coli as compared to yeast. However, these interesting speculations will require further comparative experimental and computational SMFS studies of both proteins.

Figure 10.

Superimposed FE curves of (A) yPGK (cyan) and (B) ecoliPGK (brown). To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 11.

Probability density functions contour plot for force peaks from the FE data of both yPGK and ecPGK. The peak numbers are marked in Fig. 10. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

PGK is a model protein for analyzing the unfolding and refolding behavior of multidomain proteins and examining the effects of domain-domain interactions on folding pathways. Previous studies showed different unfolding pathways for full-length yPGK under different denaturing conditions. For example, cold denaturation causes yPGK to unfold through a two-state process (115, 116), whereas GmdHCl denaturation causes yPGK to unfold sequentially, starting from the C-terminal domain and followed by the N-terminal domain (70, 117). Although fluorescence-based studies suggest that both individual domains unfold independently (81, 118), in chemical unfolding of yPGK, the chemical refolding pathway of yPGK was found to be directed by domain-domain interactions in an asymmetric manner: the refolding of the N-terminal domain within the full-length protein was proposed to proceed through a completely different pathway as compared to the pathway followed by the individual N-terminal domain, whereas the refolding pathway of the individual C-terminal domain remained the same as in the full yPGK protein (20).

Our results from mechanical unfolding studies of yPGK are quite different from the previous studies. We found that after the initial mechanical rupture of the contacts between domains (peak 0) and their physical separation, yPGK does not obey only one sequential unfolding pathway but stochastically follows two unfolding pathways (N-terminal domain rupture first versus C-terminal first, Fig. 4, B and D), which can also be modulated by the individual domains. The N-terminal domain in full-length yPGK was less likely to unfold through a transient intermediate as compared to isolated yPGKNT, possibly due to differences in the mechanical forces steering the unfolding process in both cases and the partial unfolding of N-terminal domain in yPGK after peak 0 (Fig. 4 pie plots on top row), and the chance for the N-terminal domain to display a strong intermediate (13%) is much less than yPGKNT (81%). In very rare cases (2%), the C-terminal domain in full-length yPGK also unfolded through an intermediate, although there was no intermediate observed in yPGKCT-construct unfolding studies (Fig. 4 E).

With the assistance of SMD simulations, we determined that the unwound parts in both domains that did not contribute to the unfolding force peaks were the edge areas of both domains. The mechanical strength of the interface between the N-terminal domain and C-terminal domain was captured as peak 0 and may originate within the deep cleft separating them, which has been suggested to play a role in the hinge-bending rearrangement of the enzyme during catalysis (119, 120). The force-probe-insertion experiments support the findings from the truncation experiments and demonstrate the ability of the CC probe to serve both as a mechanical unfolding probe and as a unique means to modulate domain stability and alter the unfolding pathways. The comparison of the mechanical properties of yPGK and its E. coli homolog suggests significantly different energy profiles separating native and (intermediate) unfolded states for both proteins that warrant further investigation. We plan on continuing this work with additional AFS measurements using additional CC insertions and carrying out all-atom SMD simulations to capture the role of critical residues in supporting these different unfolding pathways.

Author Contributions

All authors designed the experiments. Q.L. and Z.N.S. performed experiments. All authors analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. J. Clarke (University of Cambridge, UK) for providing the pAFM 1–8 plasmid.

This work is supported by National Science Foundation grant GRFP 1106401 to Z.N.S. and by National Science Foundation grant MCB-1517245 to P.E.M.

Editor: Nancy Forde.

Footnotes

Qing Li and Zackary N. Scholl contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Materials and Methods, two figures, and one table are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30667-2.

Contributor Information

Qing Li, Email: ql29@duke.edu.

Zackary N. Scholl, Email: zns@duke.edu.

Piotr E. Marszalek, Email: pemar@duke.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Jackson S.E. How do small single-domain proteins fold? Fold. Des. 1998;3:R81–R91. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton K.V., Anderson W.J., Cordes M.H. Studying protein fold evolution with hybrids of differently folded homologs. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2015;28:241–250. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzv027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freddolino P.L., Harrison C.B., Schulten K. Challenges in protein folding simulations: timescale, representation, and analysis. Nat. Phys. 2010;6:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nphys1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best R.B., Hummer G., Eaton W.A. Native contacts determine protein folding mechanisms in atomistic simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17874–17879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311599110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Shaw D.E. How fast-folding proteins fold. Science. 2011;334:517–520. doi: 10.1126/science.1208351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekman D., Björklund Å.K., Elofsson A. Multi-domain proteins in the three kingdoms of life: orphan domains and other unassigned regions. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batey S., Randles L.G., Clarke J. Cooperative folding in a multi-domain protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;349:1045–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goh C.S., Milburn D., Gerstein M. Conformational changes associated with protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy Y., Cho S.S., Wolynes P.G. A survey of flexible protein binding mechanisms and their transition states using native topology based energy landscapes. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:1121–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steward A., Adhya S., Clarke J. Sequence conservation in Ig-like domains: the role of highly conserved proline residues in the fibronectin type III superfamily. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;318:935–940. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott K.A., Steward A., Clarke J. Titin; a multidomain protein that behaves as the sum of its parts. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;315:819–829. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones S., Marin A., Thornton J.M. Protein domain interfaces: characterization and comparison with oligomeric protein interfaces. Protein Eng. 2000;13:77–82. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Head J.G., Houmeida A., Brady R.L. Stability and folding rates of domains spanning the large A-band super-repeat of titin. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1570–1579. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)75811-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald R.I., Pozharski E.V. Free energies of urea and of thermal unfolding show that two tandem repeats of spectrin are thermodynamically more stable than a single repeat. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3974–3984. doi: 10.1021/bi0025159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitter J. The perspectives of studying multi-domain protein folding. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:1672–1681. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8771-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandts J.F., Hu C.Q., Mos M.T. A simple model for proteins with interacting domains. Applications to scanning calorimetry data. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8588–8596. doi: 10.1021/bi00447a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semisotnov G.V., Vas M., Sinev M.A. Refolding kinetics of pig muscle and yeast 3-phosphoglycerate kinases and of their proteolytic fragments. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;202:1083–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freire E., Murphy K.P., Privalov P.L. The molecular basis of cooperativity in protein folding. Thermodynamic dissection of interdomain interactions in phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:250–256. doi: 10.1021/bi00116a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szilágyi A.N., Vas M. Sequential domain refolding of pig muscle 3-phosphoglycerate kinase: kinetic analysis of reactivation. Fold. Des. 1998;3:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(98)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osváth S., Köhler G., Fidy J. Asymmetric effect of domain interactions on the kinetics of folding in yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1609–1616. doi: 10.1110/ps.051359905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartl F.U., Hayer-Hartl M. Converging concepts of protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:574–581. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiti F., Dobson C.M. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osváth S., Jäckel M., Fidy J. Domain interactions direct misfolding and amyloid formation of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Proteins. 2006;62:909–917. doi: 10.1002/prot.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuman K.C., Nagy A. Single-molecule force spectroscopy: optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers and atomic force microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:491–505. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borgia A., Williams P.M., Clarke J. Single-molecule studies of protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:101–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.060706.093102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann T., Dougan L. Single molecule force spectroscopy using polyproteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:4781–4796. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noy A., Friddle R.W. Practical single molecule force spectroscopy: how to determine fundamental thermodynamic parameters of intermolecular bonds with an atomic force microscope. Methods. 2013;60:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodside M.T., Block S.M. Reconstructing folding energy landscapes by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2014;43:19–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scholl Z.N., Li Q., Marszalek P.E. Single molecule mechanical manipulation for studying biological properties of proteins, DNA, and sugars. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2014;6:211–229. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, Q., Z. N. Scholl, and P. E. Marszalek. 2014. Nanomechanics of single biomacromolecules. In Handbook of Nanomaterials Properties, B. Bhushan, D. Luo, S. R. Schricker, et al., eds. (Springer), pp. 1077–1123.

- 31.Scholl Z.N., Li Q., Marszalek P.E. Single-molecule force spectroscopy reveals the calcium dependence of the alternative conformations in the native state of a βγ-crystallin protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:18263–18275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.729525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholl Z.N., Yang W., Marszalek P.E. Chaperones rescue luciferase folding by separating its domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:28607–28618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.582049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee G., Abdi K., Marszalek P.E. Nanospring behaviour of ankyrin repeats. Nature. 2006;440:246–249. doi: 10.1038/nature04437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serquera D., Lee W., Itzhaki L.S. Mechanical unfolding of an ankyrin repeat protein. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1294–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee W., Zeng X., Marszalek P.E. Mechanical anisotropy of ankyrin repeats. Biophys. J. 2012;102:1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wetzel S.K., Settanni G., Plückthun A. Folding and unfolding mechanism of highly stable full-consensus ankyrin repeat proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;376:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Junker J.P., Rief M. Single-molecule force spectroscopy distinguishes target binding modes of calmodulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14361–14366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904654106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal V., Kulothungan S.R., Ainavarapu S.R. Ligand-modulated parallel mechanical unfolding pathways of maltose-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:28056–28065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertz M., Rief M. Ligand binding mechanics of maltose binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;393:1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertz M., Rief M. Mechanical unfoldons as building blocks of maltose-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandal S.S., Merz D.R., Žoldák G. Nanomechanics of the substrate binding domain of Hsp70 determine its allosteric ATP-induced conformational change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:6040–6045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619843114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauer D., Merz D.R., Žoldák G. Nucleotides regulate the mechanical hierarchy between subdomains of the nucleotide binding domain of the Hsp70 chaperone DnaK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10389–10394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504625112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jahn M., Rehn A., Hugel T. The charged linker of the molecular chaperone Hsp90 modulates domain contacts and biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:17881–17886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414073111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberhauser A.F., Hansma P.K., Fernandez J.M. Stepwise unfolding of titin under force-clamp atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:468–472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021321798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marszalek P.E., Lu H., Fernandez J.M. Mechanical unfolding intermediates in titin modules. Nature. 1999;402:100–103. doi: 10.1038/47083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrion-Vazquez M., Oberhauser A.F., Fernandez J.M. Mechanical and chemical unfolding of a single protein: a comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3694–3699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrion-Vazquez M., Marszalek P.E., Fernandez J.M. Atomic force microscopy captures length phenotypes in single proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11288–11292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwaiger I., Sattler C., Rief M. The myosin coiled-coil is a truly elastic protein structure. Nat. Mater. 2002;1:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nmat776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gebhardt J.C., Clemen A.E., Rief M. Myosin-V is a mechanical ratchet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8680–8685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510191103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Law R., Carl P., Discher D.E. Cooperativity in forced unfolding of tandem spectrin repeats. Biophys. J. 2003;84:533–544. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74872-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Batey S., Scott K.A., Clarke J. Complex folding kinetics of a multidomain protein. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2120–2130. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rief M., Pascual J., Gaub H.E. Single molecule force spectroscopy of spectrin repeats: low unfolding forces in helix bundles. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;286:553–561. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee W., Zeng X., Marszalek P.E. Full reconstruction of a vectorial protein folding pathway by atomic force microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:38167–38172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leckband D., Sivasankar S. Biophysics of cadherin adhesion. In: Harris T., editor. Adherens Junctions: From Molecular Mechanisms to Tissue Development and Disease. Springer; 2012. pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leckband D., Sivasankar S. Cadherin recognition and adhesion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2012;24:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rief M., Gautel M., Gaub H.E. The mechanical stability of immunoglobulin and fibronectin III domains in the muscle protein titin measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 1998;75:3008–3014. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77741-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oberhauser A.F., Badilla-Fernandez C., Fernandez J.M. The mechanical hierarchies of fibronectin observed with single-molecule AFM. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:433–447. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oberhauser A.F., Marszalek P.E., Fernandez J.M. The molecular elasticity of the extracellular matrix protein tenascin. Nature. 1998;393:181–185. doi: 10.1038/30270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saibil H. Chaperone machines for protein folding, unfolding and disaggregation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:630–642. doi: 10.1038/nrm3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maillard R.A., Chistol G., Bustamante C. ClpX(P) generates mechanical force to unfold and translocate its protein substrates. Cell. 2011;145:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zoldák G., Rief M. Force as a single molecule probe of multidimensional protein energy landscapes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walder R., LeBlanc M.A., Perkins T.T. Rapid characterization of a mechanically labile α-helical protein enabled by efficient site-specific bioconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9867–9875. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu H., Siewny M.G., Perkins T.T. Hidden dynamics in the unfolding of individual bacteriorhodopsin proteins. Science. 2017;355:945–950. doi: 10.1126/science.aah7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osváth S., Sabelko J.J., Gruebele M. Tuning the heterogeneous early folding dynamics of phosphoglycerate kinase. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watson H.C., Walker N.P., Tuite M.F. Sequence and structure of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. EMBO J. 1982;1:1635–1640. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bryant T.N., Watson H.C., Wendell P.L. Structure of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Nature. 1974;247:14–17. doi: 10.1038/247014a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rossman M.G., Liljas A. Letter: Recognition of structural domains in globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;85:177–181. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minard P., Hall L., Yon J.M. Efficient expression and characterization of isolated structural domains of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Protein Eng. 1989;3:55–60. doi: 10.1093/protein/3.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Missiakas D., Betton J.M., Yon J.M. Unfolding-refolding of the domains in yeast phosphoglycerate kinase: comparison with the isolated engineered domains. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8683–8689. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Missiakas D., Betton J.M., Yon J.M. Kinetic studies of the refolding of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase: comparison with the isolated engineered domains. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1485–1493. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griko Yu. V., Venyaminov S. Yu., Privalov P.L. Heat and cold denaturation of phosphoglycerate kinase (interaction of domains) FEBS Lett. 1989;244:276–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Damaschun G., Damaschun H., Zirwer D. Cold denaturation-induced conformational changes in phosphoglycerate kinase from yeast. Biochemistry. 1993;32:7739–7746. doi: 10.1021/bi00081a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gast K., Damaschun G., Zirwer D. Cold denaturation of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase: kinetics of changes in secondary structure and compactness on unfolding and refolding. Biochemistry. 1993;32:7747–7752. doi: 10.1021/bi00081a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Szpikowska B.K., Mas M.T. Urea-induced equilibrium unfolding of single tryptophan mutants of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase: evidence for a stable intermediate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;335:173–182. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Betton J.M., Desmadril M., Yon J.M. Detection of intermediates in the unfolding transition of phosphoglycerate kinase using limited proteolysis. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5421–5428. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ritco-Vonsovici M., Minard P., Yon J.M. Is the continuity of the domains required for the correct folding of a two-domain protein? Biochemistry. 1995;34:16543–16551. doi: 10.1021/bi00051a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pecorari F., Guilbert C., Yon J.M. Folding and functional complementation of engineered fragments from yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3465–3476. doi: 10.1021/bi951973s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Osváth S., Quynh L.M., Smeller L. Thermodynamics and kinetics of the pressure unfolding of phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10146–10150. doi: 10.1021/bi900922f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ervin J., Larios E., Gruebele M. What causes hyperfluorescence: folding intermediates or conformationally flexible native states? Biophys. J. 2002;83:473–483. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sabelko J., Ervin J., Gruebele M. Observation of strange kinetics in protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6031–6036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beechem J.M., Sherman M.A., Mas M.T. Sequential domain unfolding in phosphoglycerate kinase: fluorescence intensity and anisotropy stopped-flow kinetics of several tryptophan mutants. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13943–13948. doi: 10.1021/bi00042a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wilson H.R., Williams R.J., Watson H.C. NMR analysis of the interdomain region of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;170:529–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ritco-Vonsovici M., Mouratou B., Guittet E. Role of the C-terminal helix in the folding and stability of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:833–841. doi: 10.1021/bi00003a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lillo M.P., Beechem J.M., Mas M.T. Design and characterization of a multisite fluorescence energy-transfer system for protein folding studies: a steady-state and time-resolved study of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11261–11272. doi: 10.1021/bi9707887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ebbinghaus S., Dhar A., Gruebele M. Protein folding stability and dynamics imaged in a living cell. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dhar A., Ebbinghaus S., Gruebele M. The diffusion coefficient for PGK folding in eukaryotic cells. Biophys. J. 2010;99:L69–L71. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dhar A., Girdhar K., Gruebele M. Protein stability and folding kinetics in the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum of eucaryotic cells. Biophys. J. 2011;101:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guo M., Xu Y., Gruebele M. Temperature dependence of protein folding kinetics in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17863–17867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201797109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dobson M.J., Tuite M.F., Fothergill L.A. Conservation of high efficiency promoter sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:2625–2637. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.8.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee E.H., Hsin J., Schulten K. Discovery through the computational microscope. Structure. 2009;17:1295–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rico F., Gonzalez L., Scheuring S. High-speed force spectroscopy unfolds titin at the velocity of molecular dynamics simulations. Science. 2013;342:741–743. doi: 10.1126/science.1239764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Steward A., Toca-Herrera J.L., Clarke J. Versatile cloning system for construction of multimeric proteins for use in atomic force microscopy. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2179–2183. doi: 10.1110/ps.0212702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scholl Z.N., Marszalek P.E. Improving single molecule force spectroscopy through automated real-time data collection and quantification of experimental conditions. Ultramicroscopy. 2014;136:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Florin E.L., Rief M., Gaub H.E. Sensing specific molecular interactions with the atomic force microscope. Biosens. Bioelectron. 1995;10:895–901. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bustamante C., Marko J.F., Smith S. Entropic elasticity of lambda-phage DNA. Science. 1994;265:1599–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.8079175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marko J.F., Siggia E.D. Stretching DNA. Macromolecules. 1995;28:8759–8770. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Noel J.K., Whitford P.C., Onuchic J.N. SMOG@ctbp: simplified deployment of structure-based models in GROMACS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W657–W661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clementi C., Nymeyer H., Onuchic J.N. Topological and energetic factors: what determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en-route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pronk S., Páll S., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schwaiger I., Kardinal A., Rief M. A mechanical unfolding intermediate in an actin-crosslinking protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:81–85. doi: 10.1038/nsmb705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Evans E., Halvorsen K., Wong W.P. A new approach to analysis of single-molecule force measurements. In: Hinterdorfer P., van Oijen A., editors. Handbook of Single-Molecule Biophysics. Springer; 2009. pp. 571–589. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dudko O.K., Hummer G., Szabo A. Theory, analysis, and interpretation of single-molecule force spectroscopy experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15755–15760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806085105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Y., Dudko O.K. A transformation for the mechanical fingerprints of complex biomolecular interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:16432–16437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309101110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lu H., Schulten K. Steered molecular dynamics simulations of force-induced protein domain unfolding. Proteins. 1999;35:453–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dietz H., Rief M. Protein structure by mechanical triangulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1244–1247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509217103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sen Mojumdar S., N Scholl Z., Woodside M.T. Partially native intermediates mediate misfolding of SOD1 in single-molecule folding trajectories. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1881. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01996-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thirumalai D., Klimov D., Woodson S. Kinetic partitioning mechanism as a unifying theme in the folding of biomolecules. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1997;96:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mickler M., Dima R.I., Rief M. Revealing the bifurcation in the unfolding pathways of GFP by using single-molecule experiments and simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20268–20273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705458104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Peng Q., Li H. Atomic force microscopy reveals parallel mechanical unfolding pathways of T4 lysozyme: evidence for a kinetic partitioning mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706775105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pierse C.A., Dudko O.K. Distinguishing signatures of multipathway conformational transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;118:088101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li Q., Scholl Z.N., Marszalek P.E. Capturing the mechanical unfolding pathway of a large protein with coiled-coil probes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:13429–13433. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang L., Rivera E.V., Nall B.T. Loop entropy and cytochrome c stability. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;353:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Young T.A., Skordalakes E., Marqusee S. Comparison of proteolytic susceptibility in phosphoglycerate kinases from yeast and E. coli: modulation of conformational ensembles without altering structure or stability. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1438–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stigler J., Ziegler F., Rief M. The complex folding network of single calmodulin molecules. Science. 2011;334:512–516. doi: 10.1126/science.1207598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Damaschun G., Damaschun H., Zirwer D. Denatured states of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 1998;63:259–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gast K., Damaschun G., Zirwer D. Cold denaturation of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase: which domain is more stable? FEBS Lett. 1995;358:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ptitsyn O.B., Pain R.H., Razgulyaev O.I. Evidence for a molten globule state as a general intermediate in protein folding. FEBS Lett. 1990;262:20–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lillo M.P., Szpikowska B.K., Beechem J.M. Real-time measurement of multiple intramolecular distances during protein folding reactions: a multisite stopped-flow fluorescence energy-transfer study of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11273–11281. doi: 10.1021/bi970789z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hosszu L.L., Craven C.J., Waltho J.P. Is the structure of the N-domain of phosphoglycerate kinase affected by isolation from the intact molecule? Biochemistry. 1997;36:333–340. doi: 10.1021/bi961784p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Banks R.D., Blake C.C., Phillips A.W. Sequence, structure and activity of phosphoglycerate kinase: a possible hinge-bending enzyme. Nature. 1979;279:773–777. doi: 10.1038/279773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rotkiewicz P., Skolnick J. Fast procedure for reconstruction of full-atom protein models from reduced representations. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1460–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.