Abstract

Kidney transplant patients treated with belatacept without depletional induction experience higher rates of acute rejection compared to patients treated with conventional immunosuppression. Costimulation blockade-resistant rejection (CoBRR) is associated with terminally differentiated T cells. Alemtuzumab induction and belatacept/sirolimus immunotherapy effectively prevents CoBRR. We hypothesized that cells in late phases of differentiation would be selectively less capable of repopulating post-depletion than more naïve phenotypes, providing a potential mechanism by which lymphocyte depletion and repopulation could reduce the risk of CoBRR. Lymphocytes from 20 recipients undergoing alemtuzumab-induced depletion and belatacept/sirolimus immunosuppression were studied longitudinally for markers of maturation (CCR7, CD45RA, CD57, PD1), recent thymic emigration (CD31), and the interleukin-7 receptor-α (IL-7Rα). Serum was analyzed for IL-7. Alemtuzumab induction produced profound lymphopenia followed by repopulation, during which naïve IL-7Rα+CD57−PD1− cells progressively became the predominant subset. This did not occur in a comparator group of 10 patients treated with conventional immunosuppression. Serum from depleted patients showed markedly elevated IL-7 levels posttransplantation. Sorted CD57−PD1− cells demonstrated robust proliferation in response to IL-7, while more differentiated cells proliferated poorly. These data suggest that differences in IL-7-dependent proliferation is one exploitable mechanism distinguishing CoB-sensitive and CoB-resistant T cell populations to reduce the risk of CoBRR. ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT00565773

Introduction

Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-based conventional immunotherapy nonspecifically inhibits naïve and memory T cell activation, effectively preventing allograft rejection(1). However, the anti-rejection effects come at the expense of impaired T cell-mediated protective immunity(2) and numerous off-target side effects(3). As such, efforts have been made to replace CNIs with a maintenance regimen with greater specificity for inhibiting alloreactive T cell-mediated immunity.

Belatacept, a CTLA-4 fusion protein, blocks CD28/B7 costimulation signals during the interaction between T cells and antigen-presenting cells. Belatacept has demonstrated efficacy in preventing T cell-mediated allograft rejection without causing significant off-target side effects(4). However, patients treated with belatacept-based immunotherapy without lymphocyte depletional induction therapy experience significantly higher acute rejection rates than patients treated with CNI-based immunosuppressive regimens(5), a condition called costimulation blockade-resistant rejection (CoBRR)(6–7).

Lymphocyte depletion with alemtuzumab prior to kidney transplantation effectively reduces the risk of CoBRR(8–9). Indeed, depletional induction and belatacept/sirolimus-based regimens without CNIs or steroids uniquely alters the T cell immune profile by inducing a repertoire enriched for CD2lowCD28+ cells, which are permissive for costimulation blockade–mediated control of allospecific T cell activation(10–11). Furthermore, alemtuzumab-treated patients demonstrate increased numbers of regulatory T and B cells that may prevent alloimmune responses(10–11). More recent studies have identified a correlation between a high frequency of terminally differentiated CD4+CD57+PD1− T cells prior to kidney transplantation and CoBRR in non-depleted patients treated with belatacept-based maintenance regimens when compared with recipients treated with CNI-based regimens(12). Indeed, memory T cells with the ability to produce granzymes and activating cytokines express CD57, increasing the risk of long-term kidney allograft dysfunction(13).

In this report, we examine the T cell populations emerging following alemtuzumab-mediated depletion in the presence of belatacept to examine their phenotype as it relates to costimulation dependence. We compare them to non-depleted patients on standard tacrolimus-based immunosuppression, to identify differences that could influence the occurrence of CoBRR post-transplant, or during conversion from conventional immunosuppression to belatacept. We find that lymphocyte depletion with alemtuzumab and the subsequent lymphocyte repopulation, creates a repertoire with a decreased frequency and absolute number of differentiated T cell phenotypes, including cells expressing CD57+. We also demonstrate an increased frequency of CD31 expressing cells during T cell repopulation characterized mainly as naïve cells, suggesting a thymic origin. We further find that renal transplant recipients have higher levels of circulating IL-7 following depletion than under conventional circumstances, and that less differentiated CD57− T cells express higher levels of the IL-7 receptor alpha chain (CD127). Since IL-7 is a critical mediator of homeostatic proliferation(14), we posit that CD57− T cells have a proliferative advantage during post-depletional lymphocyte reconstitution.

These findings identify a mechanistic explanation for the decreased frequency and absolute cell number of CD57+ T cells following lymphocyte-depletion-induced repopulation. We hypothesize that the favorable clinical performance of belatacept following depletional induction therapy is due in part to reconstitution of a costimulation-sensitive CD57− T cell repertoire.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients, immunosuppression and follow-up

Twenty patients were enrolled under an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved, Food and Drug Administration-sponsored clinical trial following informed consent. All patients were seropositive for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and free of donor-specific antibodies. Calculated panel reactive antibody was ≤20% at enrollment. Each patient received a kidney allograft from either a living related or unrelated donor.

Immunosuppression consisted of alemtuzumab induction followed by maintenance immunosuppressive therapy with belatacept and sirolimus, as previously reported(10). Patients were monitored weekly for the first month, monthly until 6 months, and then every 6 months until 36 months post-transplantation. Peripheral blood from patients was collected pre- and post-transplantation, and during each visit. An additional 10 patients served as the comparator group to reference the findings of the trial patients versus the standard use of tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. The comparator patients were treated with basiliximab induction and a maintenance regimen consisting of tacrolimus (trough levels 5–10 ng/mL), mycophenolate mofetil (1000 mg), and prednisone (5 mg). These patients were selected for similar freedom from rejection and clinical stability, and were also enrolled under an IRB-approved immune monitoring protocol following informed consent.

Reagents and monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) anti-CD3-Alexa-700, anti-CD3-PerCP, anti-CD4-V450, anti-CD4-PE, anti-CD8-PacBlue, anti-CD16-FITC, anti-CD20-PECy7, anti-CD20-APCCy7, anti-CD31-FITC, anti-CD45-PerCP, anti-CD56-APC, anti-CD57-FITC, anti-CD57-BV605, anti-CD127 (IL-7Rα)-APC, and anti-CCR7-PECy7 were purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Anti-CD45RA-QDOT655 was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-CD8-APC-eFluor-780 and anti-PD1-PE were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Recombinant human IL-7 and IL-7 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cells and flow cytometry

Absolute lymphocyte subsets were determined using BD Trucount tubes (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 50 μl of blood was added into a Trucount tube and incubated with mAbs specific to CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16, CD20, CD45, and CD56 for 15 minutes followed by incubation with Lysing Solution (Invitrogen) for 10 minutes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from blood collected before and after transplantation by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Cells were re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% fetal bovine serum. A minimum of 105 PBMCs were surface-stained with mAbs directed for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD57, PD1, CD45RA, CCR7, and IL-7Rα and analyzed using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences LSR II). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Measurement of serum IL-7

To determine the serum IL-7 levels during T cell repopulation after alemtuzumab induction, a standard ELISA was performed on serial serum samples in duplicate using human IL-7 kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Serum samples longitudinally collected from patients treated with conventional maintenance immunosuppressive regimen were used as a reference comparator.

Purification of CD57+ and CD57− cells and proliferation assay

To assess the proliferation of CD57−PD1− and CD57+ and/or PD1+ T cells, a VPD450-based lymphocyte proliferation was performed. Briefly, PBMCs were isolated from blood obtained from normal healthy volunteers. Pan-T cells were purified using a negative selection kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Purified T cells were incubated with anti-CD57-BV605 and anti-PD1-PE at 4°C for 15 min followed by one wash with medium, and re-suspended in RPMI-1640 medium. CD57−PD1− and CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells were sorted with BD Diva-sorter. Purified cells were labeled with 1 mM VPD450, and 5 × 105 cells were incubated in RPMI-1640 medium containing 20% human AB serum with or without 50 ng/mL recombinant IL-7 at 37°C for 10 days. Cells were collected and surface-stained with mAb directed to CD3, CD4, CD8, and IL-7Rα for 15 minutes. Cells were analyzed using flow cytometry, and the data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA with post-testing for linear trend was performed to compare variables pre- and post-transplantation. Unpaired Student’s t-test was performed to determine the statistical significance for IL-7 receptor expression between CD57−PD1− and CD57+ and/or PD1+ T cells. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Profound lymphocyte depletion by alemtuzumab induction and prevention of acute allograft rejection

As previously reported, profound lymphocyte depletion was achieved immediately following alemtuzumab therapy followed by slow CD4+ and CD8+ cell reconstitution and a relatively rapid B cell repopulation(10–11). Alemtuzumab induction and belatacept/sirolimus-based immunosuppression effectively prevented T cell-mediated allograft rejection within 36 months post-transplantation. All patients demonstrated excellent renal allograft function with sustained and improving estimated GFR(10) and intact T cell-mediated anti-cytomegalovirus and EBV responses(11) post-transplantation. No T cell depletion was seen in the non-depleted, conventionally treated patients. These patients were selected for analysis based on a similarly stable course.

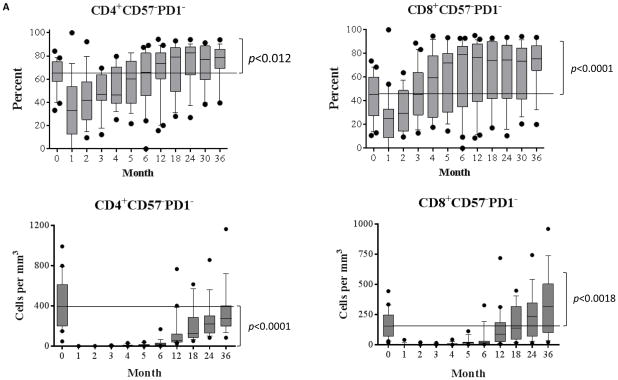

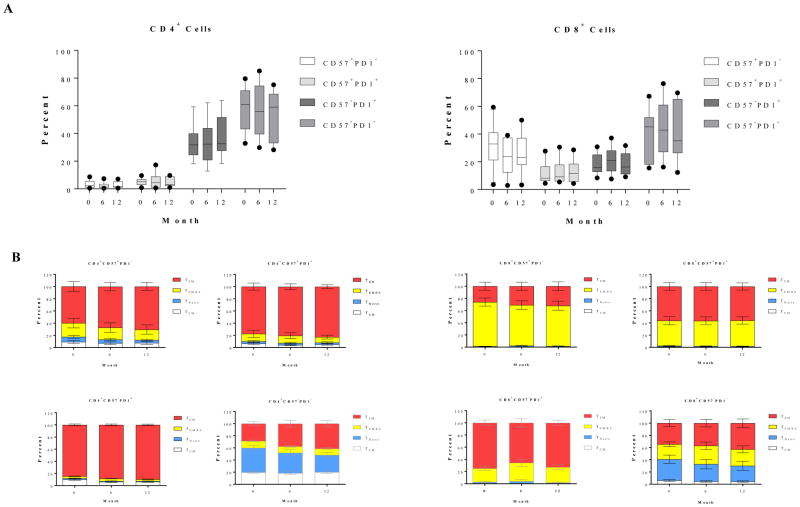

Homeostatic reconstitution with alemtuzumab induction and belatacept/sirolimus therapy produces CD57−PD1− frequency skewing toward naïve phenotype

Human T cells can be segregated into four distinct subsets based on CD45RA/CCR7 classification(15): central memory (TCM, CD45RA−CCR7+), naïve (TNaïve, CD45RA+CCR7+), terminally differential effector memory (TEMRA, CD45RA+ CCR7−), and effector memory (TEM, CD45RA− CCR7−). Additional markers of activation and differentiation include CD57 and PD1. The immediate post-depletional repertoire was characterized by a very small number of T cells, disproportionately enriched for TEMRA and TEM cells, and similarly disproportionately expressing CD57 and PD1, in both the CD4+ and CD8+ populations (Figure 1A). This is consistent with previous observations in patients treated with depletional induction(16). During the first month, there was relatively little change in cell count, attributed to the residual effects of alemtuzumab. However, as repopulation proceeded, the new repertoire progressively became more naïve, returning to a baseline percentage distribution within 3 months and thereafter developing a progressively more naïve expression pattern. Despite the marked shift toward a naïve phenotype, the absolute number of CD4+CD57−PD1− naive cells remained below baseline levels, even 36 months post-transplantation. In contrast, absolute numbers of CD8+CD57−PD1− cells repopulated to baseline levels between 12 and 18 months, and increased constantly above baseline levels after 18-months post-transplantation. As shown in Figure 1B, there was a high percentage of memory subsets including TEM, TEMRA, and TCM cells within the CD57−PD1− subset prior to alemtuzumab induction. A transient increased percentage of TEMRA subset in CD57−PD1− cells was observed for approximately two to four months post-depletion. In contrast, a significant reduction of the TEM subset frequency in both CD4+ and CD8+CD57−PD1− cells was observed, and most importantly, the CD57−PD1− subset skewed toward naïve cells during lymphocyte repopulation. At the end of the study period, this distribution was dominated by TNaïve cells. Therefore, the resultant effect of the depletional event disproportionately eliminated TNaïve cells, while the process of post depletional repopulation disproportionately selected for naïve, CD57−, and PD1− cells—cells known to be typically susceptible to CoB-based immunosuppression.

Figure 1. Post-depletional homeostatic reconstitution of CD4+ and CD8+ CD57−PD1− cells after kidney allograft transplantation.

(A) CD57−PD1− subset in both CD4+ and CD8+ populations demonstrated a transit reduction post-alemtuzumab induction, and increased constantly above baseline levels after 12 months post-transplantation. The absolute numbers of CD4+CD57−PD1− cells remained below baseline levels (p<0.0001). In contrast, absolute numbers of CD8+CD57−PD1− cells returned to baseline levels between 12 and 18 months post-transplantation, and continually increased above baseline levels therefore (p<0.0018). (B) CD57−PD1− cells prior to depletional induction contained large fractions of TCM, TEM, and TEMRA subsets. The frequency of CD4+ TEMRA cells increased slightly post-depletion and then returned to normal levels 3 months post-depletion induction. The frequency of CD8+ TEMRA cells demonstrated a transient increase within 4 months post-alemtuzumab induction, and returned to baseline levels thereafter. A significant reduction of TEM subset in CD57−PD1− cells was observed thereafter, and the CD57−PD1− subset significantly skewed toward naïve cells during homeostatic reconstitution. *p<0.05, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001

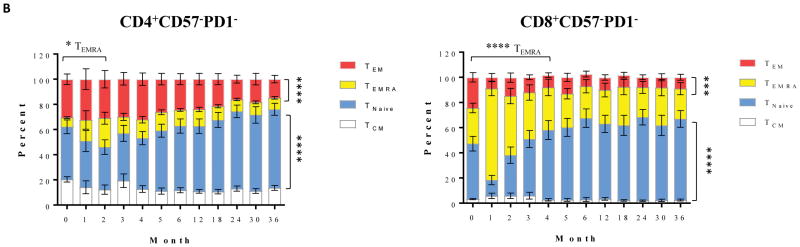

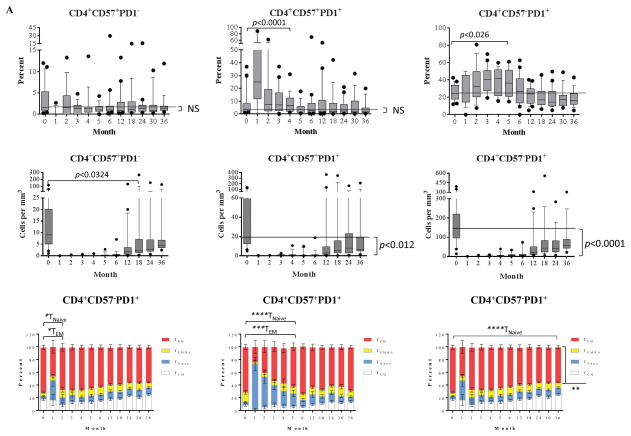

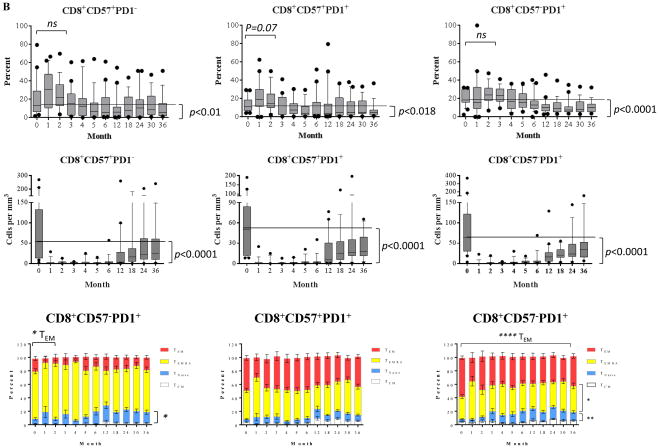

CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells are resistant to alemtuzumab induction but progressively less represented as homeostatic reconstitution proceeds

We have previously shown a correlation between a high frequency of CD4+CD57+ cells, a rare subset in healthy controls, prior to transplantation, and CoBRR in patients receiving non-depletional induction(12). In this study, we noted a burst of PD1+ cells (regardless of CD57 expression), indicating that PD+ cells contributed to the lymphocyte repopulation. Specifically, the frequency of the PD1+ subsets with or without CD57 expression demonstrated a significant increase within 5 months post-transplantation, and then returned to baseline levels. When repopulation was over, the residual subsets were selected for a more PD1-negative population between 18 to 36 months post-transplantation. We found that PD1+ CD4 cells, cells that may be more susceptible to PD1–PD1 ligand-mediated negative regulation, actively participated in repopulation. These subsets were indeed phenotypically TEMRA and TEM cells prior to depletional induction. PD1+ cells demonstrated an increased proportion of TNaïve cells during repopulation, and a reduced frequency of TEM cells. Although the percentage of more differentiated subsets were elevated early following depletion, their very low absolute number suggested that they were residual, rather than participating in a meaningful repopulation. In contrast, rapid division and repopulation was seen later post-transplant, and became progressively dominated by more naïve phenotypes.

As shown in Figure 2B, CD8+ cells demonstrated a similar phenomenon during early reconstitution as characterized by a significant decrease of frequency for PD1+ subsets with or without CD57 expression 6 months post-transplantation. The percentage of the CD57+PD1− subset exceed that at baseline level within the first 2 months post-depletion, but was exceeding low in absolute number. As the absolute number grew, this mature phenotype progressively and significantly reduced to below baseline levels 5 to 6 months post-transplantation. The most notable changes were reduced TEM subset and increased frequencies for TEMRA and TNaïve cells during PD1+ cell repopulation. Furthermore, additional analysis revealed a significant reduction of absolute numbers of these CD57 and/or PD1 expressing T cells up to 36 months post-transplantation, despite a growing absolute number of CD57−PD-1− cells.

Figure 2. Post-depletional homeostatic reconstitution of CD4+ and CD8+ CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells after kidney allograft transplantation.

(A) The dynamics of homeostatic repopulation of CD4+CD57+PD1−, CD4+CD57+PD1+, and CD4+CD57−PD1+ subsets post-alemtuzumab induction. The frequency of PD1+ subsets with or without CD57 expression increased transiently during early homeostatic repopulation post-depletion and repopulated to below baseline levels thereafter. In contrast, the absolute number of these subsets remained below baseline levels post-transplantation. The large fractions of these subsets were characterized as TCM, TEMRA, and TEM cells. PD1+ subsets demonstrated a significant reduction of TEM frequency during repopulation. (B) The dynamics of homeostatic repopulation of CD8+CD57+PD1−, CD8+CD57+PD1+, and CD8+CD57−PD1+ subsets post-alemtuzumab induction. The frequency and absolute number of these subsets significantly decreased below baseline levels significantly after transient elevation during early reconstitution, and were phenotypically TEM and TEMRA cells prior to transplantation. A significant reduction of TEM subset and increased frequency for TNaïve subset during CD57−PD1+ cell repopulation were observed.

We then longitudinally evaluated the phenotype of T cell subsets of 10 patients treated with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. As shown in Figure 3A, neither CD4+ nor CD8+ cells demonstrated a notable change in the frequency for CD57+ and PD1+ cells. Furthermore, the naïve and memory phenotypes of these T cell subsets with or without CD57 and/or PD1 expression remained unchanged post-transplantation when compared with pre-transplant baseline levels (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Dynamics and phenotype of CD57−PD1− and CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells in patients treated with non-depletional induction and CNI-based regimen.

(A) The phenotype of T cell subsets based on CD57 and PD1 expression and the frequency of CD57 and PD1 expressing of 10 patients were longitudinally assessed. (B) Pretransplant naïve and memory phenotypes of these subsets were similar to post-transplant phenotypes.

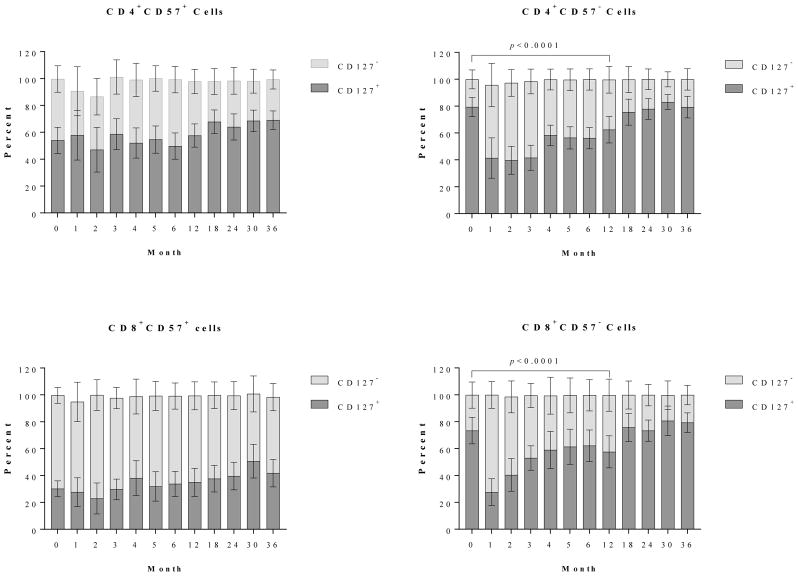

Reconstituted CD57− T cells are phenotypically IL-7Ra+ cells

IL-7 is a critical cytokine for the proliferation and expansion of IL-7Rα (CD127)-expressing T cells, particularly following periods of lymphopenia(14). In the present study, T cell proliferative expansion during post-depletional lymphocyte repopulation was defined by predominantly CD57−PD1− cells. We therefore assessed the surface expression of IL-7Rα during T cell expansion. As shown in Figure 4, CD4+ cells prior to alemtuzumab induction contained a large fraction of IL-7Rα+ cells, particularly in the subsets lacking CD57 expression. The CD4+ cells without IL-7Rα expression were resistant to depletional induction as determined by increased percentage (but very low absolute number) of IL-7Rα− cells immediately following depletion, and the percentage of IL-7Rα+ cells returned to baseline levels thereafter. CD8+CD57+ cells were predominantly IL-7Rα− cells, and the frequency remained unchanged post-depletional induction (Figure 4). Similarly, a large fraction of CD8+CD57− cells expressed IL-7Rα prior to depletional induction. A significant numerical and percentage reduction of IL-7Rα expressing CD57− cells was initially observed, but these cells repopulated to baseline levels after 12 months post-transplantation.

Figure 4. Dynamics of IL-7Rα (CD127) expressing T cells post-depletional induction.

CD4+ CD57+ cells prior to alemtuzumab induction contained a large fraction of IL-7Rα+ cells. The CD57− cells are predominantly IL-7Rα+ subset. The CD4+ cells lacking IL-7Rα expression were resistant to depletional induction during early T cell reconstitution. CD8+CD57+ cells were predominantly IL-7Rα–negative cells and remained so after depletional induction. A vast majority of CD57− CD8 cells expressed IL-7Rα prior to alemtuzumab induction, followed by significant reduction during early repopulation. The repopulating CD57− IL-7Rα+ cells returned to baseline levels at 12 months post-transplantation.

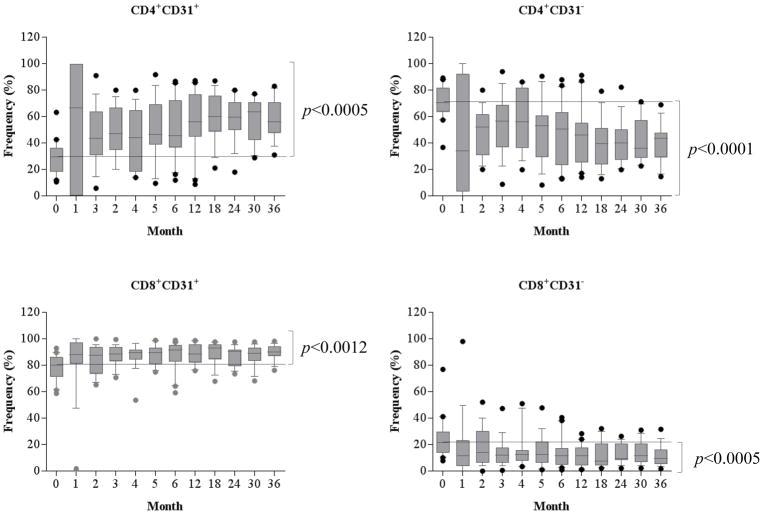

Alemtuzumab induction results in significant increase of CD31 expressing recent thymic emigrants

CD57−PD1− naïve cells are the predominant phenotype post repopulation. It has been well-established that lymphopenia-induces T cell expansion. To determine the role of thymic output in these patients treated with alemtuzumab induction, the T cells, particular CD4+ cells were analyzed based on the surface CD31 expression, a marker of recent thymic emigrants(17). As shown in Figure 5, the large fraction of CD4+ cells was CD31− cells before depletional induction. However, following alemtuzumab induction the repertoire was enriched for CD31expressing CD4+ cells, and these CD4+CD31+ cells were largely naïve (Figure S1). Unlike CD4+ cells, the CD8+CD31+ cells were predominant subset at baseline level, though the frequency of this subset also increased significantly post-transplantation (Figure 5). As repopulation proceeded, the new repertoire of CD8+CD31+ cells progressively became predominantly naïve cells when compared with baseline levels (Figure S1).

Figure 5. Homeostatic repopulation of CD31 expressing CD4+ and CD8+ cells post-depletional induction.

CD4+ and CD8+ cells demonstrated a significant increase of CD31 expressing cells and a reduction of CD31− cells post-transplantation.

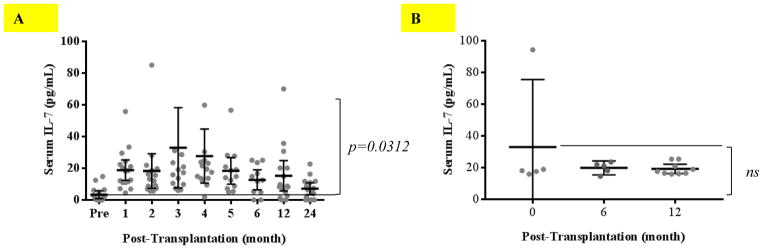

Alemtuzumab induction combined with belatacept/sirolimus therapy induces IL-7 production during T cell homeostatic reconstitution

Patients treated with alemtuzumab induction and belatacept/sirolimus immunosuppression repopulated predominantly with IL-7Rα expressing CD57−PD1− cells, skewing toward the naïve phenotype. Serum samples longitudinally collected from these patients were analyzed by ELISA to detect IL-7 levels. As shown in Figure 6A, serum IL-7 was barely detectable prior to transplantation and became significantly elevated for 12 months (p=0.0312) post-alemtuzumab induction followed by returning to baseline levels 24 months post-transplantation. In contrast, patients treated with conventional maintenance immunosuppressive regimen without depletional induction did not demonstrate elevation of serum IL-7 after transplantation (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Measurement of serum IL-7 concentrations before and after transplantation.

(A) Patients treated with alemtuzumab induction and belatacept-based immunosuppressive regimens were longitudinally analyzed for serum IL-7 as measured by ELISA. IL-7 production increased after depletional induction. (B) Patients treated with conventional immunosuppression without depletion induction did not show increased IL-7 production post-transplantation.

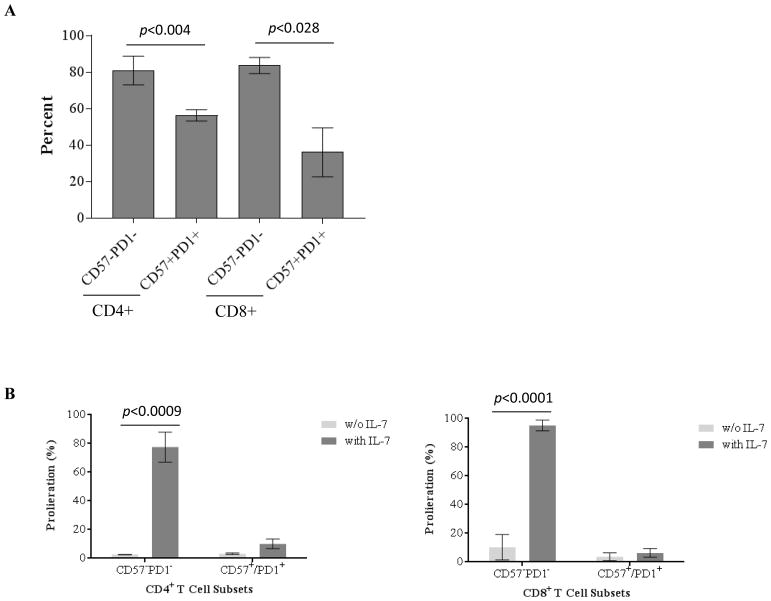

IL-7 induces CD57− T cell proliferation and expansion

Homeostasis of T cells is critical in maintaining a normal size of T cell pool or restoring T cell numbers by T cell expansion post-depletion. We demonstrated that the repopulating T cells were phenotypically CD57−PD1− subset expressing IL-7Rα. We therefore investigated the role of IL-7/IL-7Rα signaling in driving CD57−PD1− T cell proliferation and expansion in vitro. As shown in Figure 7A, purified CD57−PD1− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells demonstrated significantly higher IL-7Rα expression than purified CD57+ and/or PD1+ T cells. Purified CD57+ and/or PD1+ T cells demonstrated barely detectable proliferation in the presence of IL-7 (Figure 7B). In contrast, CD4+ and CD8+ CD57−PD1− T cells demonstrated robust proliferation in response to IL-7 (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Proliferation of purified CD57−PD1− and CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells in response to IL-7.

Purified CD57−PD1− and CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells were verified by flow cytometry and labeled with BD VPD-450. Following incubation with or without IL-7, the proliferation of T cell subsets was analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) CD57−PD1− cells demonstrated significant higher frequency of IL-7Rα (CD127)-expressing cells than purified CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells. (B) The purified CD57+ and/or PD1+ cells demonstrated barely detectable proliferation in the presence of IL-7. In contrast, CD4+ and CD8+ CD57−PD1− cells demonstrated robust proliferation in response to IL-7.

DISCUSSION

CoBRR occurs in patients treated with non-depletional induction and belatacept-based maintenance immunosuppression prior to kidney transplantation(5). The activation of allo-specific memory T cells, including CD57+ T cells and other cells that through differentiation have reduced requirements for CD28-mediated costimulation, is thought to play a critical role in initiating CoBRR(6–7, 12). We recently demonstrated that a novel immunosuppression regimen of alemtuzumab induction followed by maintenance immunotherapy with belatacept and sirolimus effectively prevents CoBRR and enables some patients at low immunological risk to be weaned from sirolimus and maintain excellent graft function with belatacept monotherapy, a clear definition of costimulation sensitive immunosuppression(10). We have therefore investigated the T cell phenotype and function in these patients during the period of lymphocyte reconstitution following profound lymphocyte depletion, a period with significant opportunity to alter the immune repertoire(17). We find that alemtuzumab induction results in substantial repertoire changes that makes these recipients more responsive to belatacept-based regimens. These changes are not seen in patients treated with a conventional non-depletional regimen. These data speak both to the mechanisms involved in depletion induced costimulation sensitivity, as well as the potential mechanisms of CoBRR during conversion from patients on standard CNI regimens who have not previously undergone depletion.

CD57 is a glucuronyltransferase expressed on neurons as well as some T and natural killer cells. While CD57’s functions have remained undefined in T cells, it serves as a marker of T cell differentiation. CD57+ T cells are characterized as terminally differentiated cells lacking CD28 expression(18–19). These cells have been associated with numerous pathological inflammatory conditions(18–19, 21). CD4+CD57+PD1− cells are a potential subset that is not susceptible to CoBRR in non-depletional induction post-transplantation(12), and CD57+CD8+ T cells are associated with late graft dysfunction in kidney transplant recipients(13). Additionally, PD1-expressing activated T cells may play a key role in allograft rejection(22).

In this study, we have shown that the frequency of CD57+ cells is markedly altered through depletion and repopulation, as is the relative proportion and absolute number of naïve and memory T cell subsets. More differentiated cells demonstrate a transient increase of frequency at the time of depletion, indicating that these subsets are relatively but not absolutely, resistant to alemtuzumab induction. Indeed, CD57+ and PD1+ cells are largely memory cells, a subset resistant to antibody-mediated depletional induction as previously reported(11, 16). With repopulation, T cells undergo a significant expansion, with a transient increase of CD57−PD1+ subsets during the early phase of reconstitution, ending in a repertoire eventually characterized as enriched for CD57−PD1− cells. The absolute numbers of CD57+ and/or PD-1+ subsets remain below baseline levels post-transplantation. Certainly, large fractions of CD57−PD1− cells in these patients prior to depletion are TCM, TEMRA, and TEM cells. However, the repopulating CD57−PD1− cells demonstrate a dramatic shift toward the predominantly naïve phenotype that persists for 36 months following alemtuzumab induction. In addition, CD4+ cells are predominately CD31 expressing naïve cells indicating that thymic output likely plays an important role in generating new T cells after alemtuzumab induction followed by belatacept-based maintenance immunosuppression. Importantly, the phenotypic shift from memory to naïve subsets supports the mechanism for the efficacy of costimulation blockade–based regimens following depletional induction in preventing CoBRR.

As relates to this depletional induction-based regimen, we hypothesize that the selective expansion of naïve cells in these patients is driven at least in part by an IL-7R-mediated signaling mechanism, an important signaling pathway that has not been investigated in patients treated with lymphocyte depletion induction. In this study, we find that patients treated with alemtuzumab followed by belatacept and sirolimus have increased serum IL-7 levels during homeostatic reconstitution. Previous studies have also observed a significant elevation of IL-7 production following lymphopenia(23).

The repopulating T cells in patients treated with alemtuzumab induction disproportionately express IL-7Rα during their post-depletion expansion. It has been well established that IL-7, secreted predominantly by stromal cells(25), plays a critical role in T cell homeostasis and survival for both naïve and memory cells(26). While alemtuzumab is exceptionally effective in eliminating circulating lymphocytes(8–9), the depletion of lymphocytes within lymphoid tissue, is incomplete(26). Since lymphoid tissue contains the stromal cells that produce IL-7–producing cells, such as dendritic cells, epithelial cells, and vascular endothelial cells(23, 27–28), CD57−PD1− T cells in the lymphoid tissue can be primed for lymphopenia-responsive proliferation.

Consistent with reports from previous investigators(24–25), we find that purified CD57−PD1− cells demonstrate robust proliferation in the presence of IL-7. In contrast, CD57+ cells are unable to proliferate in response to IL-7. These findings suggest that repopulating CD57− cells expressing IL-7Rα have a selective advantage during IL-7-mediated homeostatic repopulation. Unlike CD57− T cells, CD57+ cells are phenotypically TEM and TEMRA cells expressing high levels of adhesion molecules, perforin, and granzyme B, capable of producing effector cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ following stimulation(12–13, 18–19). Since we have previously shown that CD57+ T cells are associated with CoBRR(12), the resulting CD57− T cell enriched post-depletional repertoire is surmised to be more easily controlled by belatacept.

There are several limitations that conscribe this analysis. While we have described longitudinal changes seen in the repertoire of patients treated with a novel alemtuzumab and belatacept-based regimen, we cannot ascribe the changes specifically to any particular aspect of this regimen. Given the stark departure of the trial regimen from the standard of care, a true control group for attribution of the characteristics observed would require controls for depletion, mode of depletion, CNI presence and numerous other aspects of the regimen that distinguish it from more conventional therapies. Nevertheless, the repertoire changes we observed was not observed in non-depleted, CNI treated patients, and the make-up of the repertoire in these conventionally treated patients did not skew towards a naïve phenotype. This suggests that many patients on a non-depletional, CNI-based regimen may have a repertoire that is less conducive to belatacept treatment than those in our trial, and we believe this deserves attention when considering belatacept conversion.

Overall, the present data characterize aspects of the dynamics, functional responses, and expansion mechanisms of naïve and differentiated T cells during homeostatic reconstitution in the context of kidney transplantation using alemtuzumab induction followed by belatacept/sirolimus-based immunosuppression. We find that this regimen results in the preferential homeostatic proliferation of naïve IL-7Rα-expressing CD57− T cells relative to IL-7Rα− CD57+ T cells. In contrast, patients receiving non-depletional induction and standard CNI-based immunosuppression do not significantly alter the relative frequency of these T cell subsets. We also find homeostatic expansion of naïve CD4+ cells via thymic output. From our results, we propose that the reduction in CD57+ T cells seen following lymphocyte depleting therapy is at least in part the result of selective expansion of CD57− naïve T cells during repopulation mediated by IL-7/IL-7R interactions. Overall, our findings reveal a potential explanation for the salutary effects of lymphocyte depletion in the setting of belatacept therapy in renal transplant patients, and provide insights to guide the development of subsequent costimulation blockade–based trials.

Supplementary Material

CD4+CD31+ cells prior to depletional induction contained large fractions of TNaïve cells. The frequency of TNaïve cells remained unchanged following the repopulation of CD4+CD31+ subset post-depletional induction. In contrast, CD8+CD31+ cells prior to alemtuzumab induction contained small fraction of TNaïve cells, and the frequency of TNaïve cells within repopulating CD8+CD31+ subset demonstrated a significant increase post-transplantation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grants from the United States Food and Drug Administration (1R01 FD003539-01, ADK), the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI097423, ADK) and a Roche Organ Transplant Research Foundation grant (346678023, HX).

The authors thank the members of the Emory Transplant Center and Duke Transplant Center Biorepositories for sample collection and storage. We also acknowledge the expert clinical management of Anthony Guasch and the superb research coordination of Ada Ghali in the conduct of this trial.

Abbreviations

- CoBRR

costimulation blockade resistant rejection

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- IL-7

interleukin 7

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- CNIs

calcineurin inhibitors

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- TNaïve

naïve T cells

- TCM

central memory T cells

- TEM

effector memory T cells

- TEMRA

terminally differential effector memory T cells

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Thompson B, Gustafson SK, Schnitzler MA, Cherikh WS, Wainright JL, Snyder JJ, Israni AK, Kasiske BL. OPTN/SRTR 2012 annual data report. Kidney Am J Transplant. 2014;14:11–44. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Issa N, Fishman J. Infectious complications of antilymphocyte therapies in solid organ transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:772–786. doi: 10.1086/597089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jevnikar A, Mannon RB. Late kidney allograft loss: What we know about it, and what we can do about it. Clin J AM Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:S56–S57. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincenti F, Larsen CP, Durrbach A, Wekerle T, Nashan B, Blancho G, Lang P, Grinyo J, Halloran PF, Solez K, Hagerty D, Levy E, Zhou W, Natarajan K, Charpentier B. Costimulation blockade with belatacept in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:770–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincenti F, Larsen CP, Alberu J, Bresnahan B, Garcia VD, Kohari J, Lang P, Urrea EM, Massari P, Mondragon-Ramirez G, Reyes-Acevedo R, Rice K, Rostaing L, Steinberg S, Xing J, Agarwal M, Harler MB, Charpentier B. Three-year outcomes form BENEFIT, a randomized active-controlled, parallel-group study in adult kidney transplant recipient. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:210–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo DJ, Weaver TA, Stempora L, Mehta AK, Ford ML, Larsen CP, Kirk AD. Selective targeting of human alloresponsive CD8+ effector memory T cells based on CD2 expression. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, Perez S, Cheeseman A, Mehta AK, Kirk AD. The allo- and viral-specific immunosuppressive effect of belatacept, but not tacrolimus, attenuates with progressive T cell maturation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:319–332. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calne R, Friend P, Moffatt S, Bradley A, Hale G, Firth J, Bradley J, Smith K, Waldmann H. Prope tolerance, perioperative campath 1H, and low-dose cyclosporine monotherapy in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1998;351:1701–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knechtle SJ, Pascual J, Bloom DD, Torrealba JR, Jankowska-Gan E, Burlingham WJ, Kwun J, Colvin RB, Seyfert-Margolis V, Bourcier K, Sollinger HW. Early and limited use of tacrolimus to avoid rejection in an alemtuzumab and sirolimus regimen for kidney transplantation: clinical results and immune monitoring. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1087–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirk AD, Guasch A, Xu H, Cheeseman J, Mead SI, Ghali A, Mehta AK, Wu D, Gebel H, Bray R, Horan J, Kean LS, Larsen CP, Pearson TC. Renal transplantation using belatacept without maintenance steroids or calcineurin inhibitors. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1142–1151. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu H, Samy KP, Guasch A, Mead SI, Ghali A, Mehta AK, Stempora L, Kirk AD. Postdepletion lymphocyte reconstitution during belatacept and rapamycin treatment in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:550–564. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinosa J, Herr F, Tharp G, Bosinger S, Song M, Farris AB, 3rd, George R, Cheeseman J, Stempora L, Townsend R, Durrbach A, Kirk AD. CD57+ CD4 T cells underlie belatacept-resistant allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1102–1112. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap M, Boeffard F, Clave E, Pallier A, Danger R, Giral M, Dantal J, Foucher Y, Guillot-Gueguen C, Toubert A, Soulillou JP, Brouard S, Degaugue N. Expression of highly differentiated cytotoxic terminally differentiated effector memory CD8+ T cells in a subset of clinically stable kidney transplant recipients: A potential marker for late graft dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1856–1868. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostasis of naïve and memory T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearl JP, Parris J, Hale DA, Hoffmann SC, Bernstein WB, McCoy KL, Swanson SJ, Mannon RB, Roederer M, Kirk AD. Immunocompetent T-cells with a memory-like phenotype are the dominant cell type following antibody-mediated T-cell depletion. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:465–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stock P, Kirk AD. The risk and opportunity of homeostatic repopulation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1349–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer BE, Boritz E, Wilson CC. Effects of sustained HIV-1 plasma viremia on HIV-1 Gag-specific CD4+ T cells maturation and function. J Immunol. 2004;172:3337–3347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibegbu CC, Xu Y, Harris W, Maggio D, Miller JD, Kourtis P. Expression of killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 on antigen-specific human CD8+ lymphocytes during active, latent, and resolved infection and its relation with CD57. J Immunol. 2005;174:6088–6094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenchley JM, Karandikar NJ, Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Hill BJ, Crotty LE, Casazza JP, Kuruppu J, Migueles SA, Connors M, Roederer M, Douek DC, Koup RA. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101:2711–2720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strioga M, Pasukoniene V, Characiejus D. CD8+ CD28− and CD8+ CD57+ T cells and their role in health and disease. Immunology. 2011;134:17–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pike R, Thomas N, Workman S, Ambrose L, Guzman D, Sivakumaran S, Johnson M, Thorburn D, Harber M, Chain B, Stauss HJ. PD1-expressing T cell subsets modify the rejection risk in renal transplant patients. Front Immunol. 2016;7:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller CN, Hartigan-O’Connor DJ, Lee MD, Laidlaw G, Comelissen IP, Matloubian M, Coughlin SR, McDonald DM, McCune JM. IL-7 production in murine lymphatic endothelial cells and induction in the setting of peripheral lymphopenia. Int Immunol. 2013;25:471–483. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxt012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu N, Qin X. New insights into IL-7 signaling pathways during early and late T cell development. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:187–189. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry TJ, Connick E, Falloon J, Ledeman MM, Liewhr DJ, Spritzler J, Steinberg SM, Wood LV, Yarchoan R, Zuckerman J, Landay A, Mackall CL. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2001;97:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirk AD, Hale DA, Mannon RB, David K, Hoffmann SC, Kampen R, Cendales LK, Tadaki DK, Harlan DM, Swanson SJ. Results from a human renal allograft tolerance trial evaluating the humanized CD52-specific monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (campath-1H) Transplantation. 2003;76:120–129. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000071362.99021.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroncke R, Loppnow H, Flad HD, Gerdes J. Human follicular dendritic cells and vascular cells produce interleukin-7: a potential role for interleukin-7 in the germinal center reaction. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2541–2544. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe M, Ueno Y, Yajima T, Iwao Y, Tsuchiya M, Ishikawa H, Aiso S, Hibi T, Ishii H. Interleukin 7 is produced by human intestinal epithelial cells and regulates the proliferation of intestinal mucosal lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2945–2953. doi: 10.1172/JCI118002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CD4+CD31+ cells prior to depletional induction contained large fractions of TNaïve cells. The frequency of TNaïve cells remained unchanged following the repopulation of CD4+CD31+ subset post-depletional induction. In contrast, CD8+CD31+ cells prior to alemtuzumab induction contained small fraction of TNaïve cells, and the frequency of TNaïve cells within repopulating CD8+CD31+ subset demonstrated a significant increase post-transplantation.