Abstract

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) is a systemic side-effect of low molecular weight heparin, characterized by multiple intra-epidermal hemorrhages distant from the site of injection. There have been several small case series and literature reviews on BHD, but none have captured a complete set of reported patients. We sought to describe a case of BHD with late diagnosis and completely summarize the existing English and Spanish literature with searches of Pubmed, Scopus, Ovid Embase and Ovid Medline. After narrowing to 33 relevant reports, we describe 90 reported cases worldwide from 2004 to 2017, in addition to a new case from our institution as a means of comparison. We found that BHD was common in elderly men (mean age 72 ± 12; male:female, 1.9:1) and typically occurred within 7 days of administration of anticoagulation (median 7 days ± 6.4) usually with enoxaparin use (66% of cases). Lesions occurred primarily on the extremities only (67.9% of cases). Coagulation testing was most often normal before administration, and the majority of patients had coagulation testing in therapeutic range during treatment. Most practitioners stopped anticoagulation if continued therapeutic intervention was no longer required (57% of cases), or changed therapy to another anticoagulation if continued treatment was required (14.3% of cases). Therapy was continued outright in 23% of patients. The lesions usually resolved within 2 weeks (mean days, 13.0 ± 7.4). There was no difference in time to resolution between patients who continued the culprit anticoagulant or changed to a different anticoagulant, and those who discontinued anticoagulation altogether (13.9 days vs. 12.1, p = 0.49). Four deaths have been reported in this clinical context, two specified as intracranial hemorrhage. These deaths were unrelated to the occurrence of BHD. Continuation of low-molecular weight heparins appeared to be safe in patients with BHD.

Keywords: Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, Enoxaparin, Low molecular weight heparin

Background

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) are extensively used as anticoagulation for primary and secondary prophylaxis against thrombosis, particularly in patients with malignancy. There are several known dermatological side-effects of LMWH, including injection site hematoma and skin necrosis, eczematous dermatitis, and the lesser known bullous hemorrhage dermatosis (BHD). The latter was first described in 2004 by Dyson et al. [1]. It typically presents as intra-epidermal lesions found mainly on the extremities and torso, with a black appearance. The lesions occur at sites distant from injection, suggesting a systemic mechanism. There have been several small case series on BHD, but none have captured a complete review of reported cases. The frequent use of LMWH warrants systematic review of this side-effect so clinicians recognize its characteristics and know how to intervene. We sought to describe a case of BHD at our institution and provide a complete summary of the existing English and Spanish literature.

Methods

We performed a literature search of Pubmed, Scopus, Ovid Embase and Ovid Medline. The keywords for the search were “bullous” “hemorrhagic” and “dermatitis”. Of the initial 213 search results, 51 were found to be duplicates. The remaining 162 were reviewed by title and abstract. Of these, 33 were deemed relevant to BHD, and the entire article was reviewed. The majority of the excluded search results either did not include anticoagulant use or were relevant to dermatologic diseases other than BHD.

Results

Case presentation

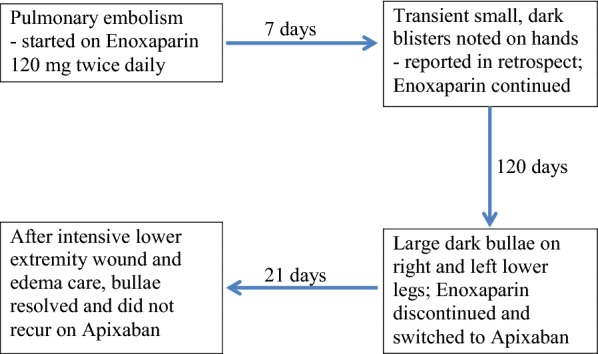

Our patient is a 62-year-old male with multiple comorbidities including morbid obesity, coronary artery disease, lipodermatosclerosis of the lower extremities, chronic peripheral venous insufficiency, and prostate cancer (Gleason 4+5) on long-term androgen deprivation therapy. He was previously treated with docetaxel for pelvic lymph node metastases. The patient also had a small renal tumor for which he was followed with imaging. He had a distant history of varicose vein ligation. While undergoing surveillance imaging to evaluate for spread of his prostate cancer, an incidental pulmonary embolism was discovered. He was started on enoxaparin 120 mg by subcutaneous injection twice daily. Within several days the patient noticed several small black blisters on his hands that resolved spontaneously. These were not reported by the patient or observed by any practitioner during routine clinic visits. The timeline of development of hemorrhagic skin lesions of this patient is outlined in Fig. 1. Four months after starting anticoagulation with enoxaparin, he presented with several large hemorrhagic bullae on his calves (Figs. 2 and 3). His coagulation values and his platelet count were within normal range. The diagnosis of bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) was made by visual inspection. Therefore, no biopsy was performed. Enoxaparin was discontinued and apixaban was started as alternative anticoagulation. The lesions healed in 3 weeks with intensive outpatient wound care and have not recurred to date while on apixaban.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of clinical events

Fig. 2.

Left anterior lower extremity bulla

Fig. 3.

Right posterior lower extremity bulla

Review of reported cases in the English and Spanish literature

We describe 90 cases of BHD discovered in our literature search, in addition to our local case (Table 1) [1–33]. Cases were reported from the US, Spain, France, Turkey, Austria, and Australia. Spain appeared to have the most representation in the literature. Serious comorbidities were common, such as carcinomas of lung, prostate, and ovary, lymphoma, and cardiomyopathy. The cases demonstrate a variety of indications and dosages for anticoagulation (not shown in table). Indications for weight-based, full dose anticoagulation included atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, aortic stenosis, left ventricular thrombus, and acute coronary syndromes. Patients also received primary prophylactic dosing for hospitalized patients. Before their incident BHD, most patients had not been exposed to anticoagulation. A minority of patients received warfarin before diagnosis; none received direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC). Most patients had normal PT and PTT values before initiation of anticoagulation, and were in therapeutic range while on treatment (not shown). A minority of patients were on aspirin at the time of diagnosis. Most patients had a punch skin biopsy, and all were negative for signs of vasculitis. Intraepidermal hemorrhage was the common pathological finding. The eruption was mainly located on the extremities, and less frequently on the torso.

Table 1.

Summary of cases (n = 91), part I, part II, part III

| References | Age | Gender | Agent | Days to lesion | Location | Intervention | Days to resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part I | |||||||

| [1] | 62 | F | Enoxaparin | Unknown | Buttock | AC changed to warfarin | 14 |

| [1] | 32 | M | Enoxaparin | 14 | Lower extremities | AC discontinued | 7 |

| [2] | 75 | M | Dalteparin | 5 | Hands and groin | AC changed to coumadin, died of IC 14 days later | Death |

| [2] | 82 | F | Tinzaparin | 6 | Extremities | AC discontinued | 10 |

| [2] | 64 | M | Heparin Calcium | 21 | Forearms and ankles | AC continued | Yes, unknown |

| [3] | 72 | F | Enoxaparin | 2 | Abdomen and upper extremities | AC changed to oral after planned intervention | 14 |

| [3] | 57 | M | Enoxaparin | 3 | Abdomen and upper and lower extremities | Unknown | Unknown |

| [4] | 88 | M | Enoxaparin then warfarin | 14 | Left arm and ankle | AC discontinued | 14 |

| [5] | 51 | Unknown | Enoxaparin then tinzaparin | 2 | Upper and lower extremities, abdomen | AC discontinued | Unknown |

| [6] | 86 | M | Enoxaparin | 1 | Trunk, extremities | AC continued | 30 |

| [6] | 87 | M | Enoxaparin | 5 | Limbs and hands | AC continued | 21 |

| [6] | 73 | F | Bemiparin then Enoxaparin | 1 | Lower extremities | Changed to rivaroxaban, died 10 days later | Death |

| [6] | 72 | M | Bemiparin | 30 | Trunk, legs | AC continued | 21 |

| [6] | 82 | M | Enoxaparin | 3 | Arms | AC continued | 21 |

| [7] | 68 | M | Enoxaparin | 8 | Hand, neck, and face | Unknown | 14 |

| [7] | 78 | M | Enoxaparin | 10 | Knees and forearm | AC continued | 14 |

| [8] | 85 | M | Enoxaparin | 3 | Torso and legs | AC discontinued | Unknown |

| [9] | 73 | M | Enoxaparin | 14 | Upper extremities | AC continued | 14 |

| [10] | 77 | M | Enoxaparin | 3 | Trunk, right hand | AC discontinued | 2 |

| [10] | 94 | M | Tinzaparin | 15 | Trunk, limbs | AC discontinued | 10 |

| [11] | 59 | F | Enoxaparin | 30 | Dorsal hand | AC continued | 4 |

| [12] | 68 | M | Enoxaparin | 1 | Feet, leg, neck, hands dorsum | AC discontinued | Unknown |

| [12] | 77 | M | Enoxaparin | 8 | Dorsum of feet, dorsum of hands | AC discontinued | Unknown |

| [13] | 88 | F | Enoxaparin | 5 | Legs | AC changed to warfarin | Unknown |

| [14] | 87 | F | Enoxaparin | 10 | Knees, forearms, elbows | Unknown | 14 |

| [15] | 71 | M | Enoxaparin | 2 | Abdomen | AC discontinued | 7 |

| [16] | 90 | M | Enoxaparin | 8 | Left arm and ankle | AC continued | 14 |

| [17] | 73 | M | Enoxaparin | 6 | Left palm | AC continued | 14 |

| Part II | |||||||

| [18] | 63 | M | Enoxaparin | 12 | Lower extremities | AC continued | 3 |

| [18] | 74 | M | Enoxaparin | 13 | Lower extremities | AC continued | 3 |

| [19] | 83 | M | Warfarin + UFH | 5 | Arms, flank, thighs | Heparin discontinued | Yes, unknown |

| [20] | 77 | M | Enoxaparin | 5 | Unknown | Changed to dabigatran | 14 |

| [21] | 82 | F | Warfarin | 10 | Extremities | Changed to enoxaparin | Worsening lesions, resolved after all AC stopped |

| [22] | 90 | M | Enoxaparin | 8 | Ankle and wrist | AC continued | 14 |

| [22] | 65 | M | Enoxaparin | 9 | Lower and upper extremities | Changed to tinzaparin as lesions persisted for 6 weeks on enoxaparin | 14 |

| [22] | 64 | M | Enoxaparin | 7 | Lower and upper extremities | AC continued | 21 |

| [22] | 89 | M | Enoxaparin | 10 | Lower and upper extremities scalp and back | AC discontinued | 21 |

| [22] | 74 | M | Enoxaparin | 20 | Hand and leg | AC discontinued | 14 |

| [23] | 71 | M | Enoxaparin | 14 | Forearms, hands, knees | AC continued | Persisting lesions for 6 months, resolved after AC stopped |

| [24] | 64 | M | Enoxaparin | 5 | Arms and hands | Dose reduced | 14 |

| [25] | 74 | M | Enoxaparin | 5 | Upper and lower extremities, abdomen | AC discontinued | 7 |

| [26] | 52 | M | Enoxaparin | 7 | Lower and upper extremities | AC continued | 3 |

| [27] | 77 | F | Enoxaparin | 15 | Limbs | AC continued | 14 |

| [28] | 77 | F | Enoxaparin | 5 | Hands and shins | AC continued, fatal ICH 4 weeks later | 12 |

| [29] | 72 | M | Enoxaparin | 7 | Arm and legs | AC changed to UFH | 7 |

| [30] | 59 | F | Enoxaparin | 270 | Legs | AC changed to fondaparinux then rivaroxaban | Unknown |

| [30] | 51 | F | Fondaparinux | Unknown | Legs | AC changed to rivaroxaban | 3 |

| [31] | 75 | F | Enoxaparin | 3 | Arms, hands, feet | AC held, lesions resolved, AC restarted and lesions re-appeared, improved with steroids, patient had past history of bullous pemphigoid | 28 |

| Part III | |||||||

| [32] | 60 | M | UFH | 5 | Limbs and trunk | AC continued | Unknown |

| [32] | 68 | F | UFH then enoxaparin | 7 | Abdomen, hands, feet | AC changed to rivaroxaban | 21 |

| [32] | 64 | M | Enoxaparin, warfarin | 9 | Lower and upper extremities | AC discontinued | 30 |

| [32] | 38 | F | UFH | 7 | Chest and ankle | AC discontinued | 7 |

| [32] | 72 | F | Enoxaparin | 2 | Forearm | AC discontinued | 2 |

| Ref. [33]; Case series of 37 cases, 1985–2015 |

77.4 | M 20 F 17 |

LMWH Fondaparinux Sodic heparin Calcic heparin |

8.8 | Limbs and trunk | AC discontinued in 34 cases AC continued in 1 case Unknown in 2 cases |

Unknown |

| Case currently reported | 62 | M | Enoxaparin | 7 | Calf and hands | AC continued with worsening lesions, after 4 months changed to apixaban | 21 after change to apixaban |

AC anticoagulation, F female, ICH intracranial hemorrhage, LMWH low molecular weight heparin, M male, UFH unfractionated heparin

Summary statistics were extracted based on our review of the literature (Table 2). The average case age was 72 ± 12, and there was a 1.9:1 male to female ratio. Enoxaparin was the most frequent culprit anticoagulant (66%), followed by fondaparinux (12%). On average, lesions appeared after 7 days of treatment (7.0 ± 6.4), and resolved after 2 weeks of discontinuation of anticoagulation (13.0 ± 7.4). Most cases of bullous lesions (67.9%) were reported on the extremities only, followed by torso and extremities (26.4% of cases). Lesions on the head and neck were rare (5.5%). Management consisted of discontinuation of culprit anticoagulant (57% of cases), continuation (23.1%), or treatment change or dose reduction (14.3%). There was no difference in time to resolution between patients who continued the culprit anticoagulant or changed to a different anticoagulant, and those who discontinued anticoagulation altogether (13.9 days vs. 12.1, p = 0.49).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics from 91 cases of BHD

| Descriptor | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age in years, average ± SD | 72 ± 12 |

| Sex % (n) | |

| Male | 64% (58) |

| Female | 36% (33) |

| Anticoagulation drug, % (n) | |

| Enoxaparin only | 66% (61) |

| Fondaparinux | 12% (11) |

| UFH only | 9% (8) |

| Bridging heparin + enoxaparin | 6.5% (6) |

| Other LMWH or ULMWH | 5.4% (5) |

| Coumadin only | 1% (1) |

| Time to lesion onset, days, mean ± SD | 7.0 ± 6.4 |

| Location % (n) | |

| Extremities only | 67.9% (36) |

| Extremities +torso | 26.4% (14) |

| Face, neck, head included | 5.7% (3) |

| Management % (n) | |

| Discontinued | 57% (52) |

| Continued | 23.1% (21) |

| Treatment changed or dose reduced | 14.3% (13) |

| Unknown | 5.5% (5) |

| Time to resolution, days, mean ± SD | 13.0 ± 7.4 |

| If continued any AC | 13.9 ± 7.8 |

| Discontinued AC | 12.1 ± 7.9 |

Discussion

The review of BHD presented here is the largest collection of cases compiled from the English and Spanish literature to our knowledge. BHD has been documented in medical reports, but appears under-recognized in the clinical practice. We also presented a case from our own institution.

BHD is a non-immune dermatological eruption related to anticoagulation given for either primary or secondary prophylaxis. Enoxaparin is the most common culprit anticoagulant, followed by fondaparinux. Lesions are distant from the site of injection. Clinical or pathological signs of inflammation are absent. The extremities are the primary sites of eruptions in many cases. BHD caused by DOACs is not specified to date from several examples of large clinical trials for VTE treatment [34–36]. No patients in our series received DOACs before diagnosis.

Our case is unusual for the delay of 4 months in the appearance of BHD consisting of very large lesions in the lower extremities. Most lesions will appear within 7 days of the first anticoagulation administration. Their appearance is usually of small, dark bullae, rather than large hemorrhagic bullae. Lesions are not painful. In retrospect, our patient did recall having small blisters on his hands that occurred within days of starting enoxaparin. However, he did not report these small skin lesions as they resolved spontaneously. He sought medical attention after developing large dark bullae on both calves.

From our viewpoint, if characteristics of BHD are present as outlined above and in Table 2, historical and clinical evaluation may be satisfactory to make the diagnosis. A biopsy should be performed if the diagnosis is in doubt. In our patient’s case, prostate cancer treatment with androgen deprivation is an unlikely cause. While injection-site granuloma and serum sickness have been reported with depot leuprolide acetate [37–39], to our knowledge, there are no reports of eruptions similar to BHD with leuprolide.

After the appearance of BHD, maintaining anticoagulation with a LMWH may increase a patient’s risk of recurrent bullae [21, 22, 31]. Nevertheless, 21 patients in our review continued on anticoagulation with a LMWH without report of recurrence. It is suspected that higher doses of LMWH may increase time to resolution of BHD [22]. No treatment is needed beyond managing anticoagulation and skin care as in this case. Discontinuing treatment may not be necessary if lesions are small.

BHD is sometimes associated with eczematous reaction at sight of injection that may suggest a type IV hypersensitivity reaction [32]. The propensity for developing lesions on the extremities in older patients also posits local trauma combined with epidermal-dermal fragility as an underlying mechanism [10]. There is no apparent association of BHD with any comorbidity. While there is no evidence indicating a higher risk for BHD with venous insufficiency, one could speculate that the pre-existing chronic leg edema in our patient facilitated the large size of the bullous lesions.

Of the 91 cases presented, there were four cases that had bleeding complications, two with fatal intracranial hemorrhage [2, 28]. Available coagulation tests were normal in these patients at the onset of anticoagulation. In Perrinaud et al. [2], the bleeding event occurred with a supratherapeutic INR. In Yurekli et al. [28], the fatal event occurred after continuing enoxaparin, but the bullous lesions had resolved at the time of death. The documented rate of intracranial hemorrhage in the CLOT trial while using LMWH for a 6-month study period was one out of 338 [40].

Conclusion

Hemorrhagic bullous dermatosis secondary to LMWH usage has been reported in the literature but is under-recognized. In this case report the diagnosis was not made until the patient presented with large hemorrhagic bullae after 4 months of LMWH. Biopsy may not be required if the clinical characteristics of BHD are present. The anticoagulation of choice may be continued if lesions are small and are resolving. Risk evaluation for bleeding may proceed along standard guidelines. This case series also highlights a need for clinical reporting of BHD when using DOACs.

Authors’ contributions

AR composed the manuscript and developed the tables. HC proposed the project. SC defined its scope and created draft summary table. AR, SC, HC, EW, and RW revised the manuscript. RBM translated Spanish articles into English. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank our patient and previous investigators who have documented their findings.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Consent for publication

Consent received from patient.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB waiver not required.

Funding

None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Armand Russo, Email: armand.russo@yale.edu.

Susanna Curtis, Email: susanna.curtis@yale.edu.

Raisa Balbuena-Merle, Email: raisa.balbuena-merle@yale.edu.

Roxanne Wadia, Email: roxanne.wadia@yale.edu.

Ellice Wong, Email: ellice.wong@yale.edu.

Herta H. Chao, Email: herta.chao@yale.edu

References

- 1.Dyson SW, Lin C, Jaworsky C. Enoxaparin sodium-induced bullous pemphigoid-like eruption: a report of 2 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(1):141–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perrinaud A, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 Suppl):S5–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltraminelli H, Itin P, Cerroni L. Intraepidermal bullous haemorrhage during anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin: two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(1):191–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzales U, et al. Remote hemorrhagic bullae occurring in a patient treated with subcutaneous heparin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(5):604–605. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thuillier D, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin-induced bullous haemorrhagic dermatosis associated with cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136(10):705–708. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maldonado Cid P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):e220–e222. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva CA, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermo Sifiliograficas. 2012;103(9):816–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixit S, Fischer G, Lim A. Haemorrhagic purpura in an elderly man. BHD. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:228–229. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pena ZG, Suszko JW, Morrison LH. Hemorrhagic bullae in a 73-year-old man. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(7):871–872. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.3364a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roux J, et al. Heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(1):105–107. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Concha-Garzon MJ, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis distant from the site of heparin injection. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(10):24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loidi Pascual L, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis induced by heparin: description of 2 new cases. Med Clin. 2014;143(11):516–517. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(4):423. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrulonis R, Marks V. Enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5 Suppl 1):AB2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deser SB, Demirag MK. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. J Card Surg. 2015;30(7):568–569. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gargallo V, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5 Suppl 1):AB144. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Öztürk S, et al. Enoxaparin-induced hemorrhagic bullous dermatosis in a leprosy patient. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2015;34(3):254–256. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2014.950381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellanos-González M, Velasco-Rodríguez D, Mancebo AB. Plaza, Bullous dermatosis at distant sites in patients treated with heparin. Med Clin. 2016;146(9):402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91(2):93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Quintana-Sancho A, Velasco-Benito V. Subcutaneous heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites. Piel. 2016;31(1):70–72. doi: 10.1016/j.piel.2015.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson A, Golden S. Hemorrhagic bullous dermatosis caused by warfarin therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2(2):156–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gargallo V, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. A report of five cases. An Bras de Dermatol. 2016;91(6):857–859. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouveia AI, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis induced by enoxaparin. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2016;35(2):160–162. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2015.1041033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Govind B, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous dermatosis: a rare heparin-induced cutaneous manifestation. Hosp Pract. 2016;44(2):103–117. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1159908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mabry A, et al. Low molecular weight heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: A case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 Suppl 1):AB60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miguel-Gomez L, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis probably associated with enoxaparin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(3):319–320. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.175915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prieto-Torres L, et al. Bullous haemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites due to enoxaparin: an uncommon secondary effect in an anticoagulated oncology patient. Semergen. 2016;42(7):504–506. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yurekli A, Caliskan E, Dogan D. Intracranial hemorrhage with fatal outcome in a patient with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Turkderm Deri Hastaliklari ve Frengi Arsivi. 2016;50(2):77–78. [Google Scholar]

- 29.An I, Harman M, Ibiloglu I. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis induced by enoxaparin. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8(5):347–349. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_355_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komforti MK, et al. A rare cutaneous manifestation of hemorrhagic bullae to low-molecular-weight heparin and fondaparinux: report of two cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(1):104–106. doi: 10.1111/cup.12821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shim JS, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis due to enoxaparin use in a bullous pemphigoid patient. Asia Pac Allergy. 2017;7(2):97–101. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2017.7.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, Alkousakis T, Winslow CY, Golitz L. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(4):393–398. doi: 10.1111/ced.13327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uceda-Martin M, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, unfractionated heparine, low molecular-weight heparin, danaparoide and fondaparinux: analysis of the French pharmacovigilance database. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2017;31:54–55. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raskob GE, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):615–624. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weitz JI, et al. Rivaroxaban or aspirin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1211–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agnelli G, et al. Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawai M, et al. A case of foreign body granuloma induced by subcutaneous injection of leuprorelin acetate horizontal line clinical analysis for 335 cases in our hospital horizontal line. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39(3):106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kluger N, et al. Cutaneous granulomas caused by subcutaneous injections of leuprorelin acetate. Presse Med. 2017;46(10):966–968. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gnanaraj J, Saif MW. Hypersensitivity vasculitis associated with leuprolide (Lupron) Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2010;29(3):224–227. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2010.487505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee AY, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.