Abstract

Introduction

Defining and accurately measuring abortion-related morbidity is important for understanding the spectrum of risk associated with unsafe abortion and for assessing the impact of changes in abortion-related policy and practices. This systematic review aims to estimate the magnitude and severity of complications associated with abortion in areas where access to abortion is limited, with a particular focus on potentially life-threatening complications.

Methods

A previous systematic review covering the literature up to 2010 was updated with studies identified through a systematic search of Medline, Embase, Popline and two WHO regional databases until July 2016. Studies from settings where access to abortion is limited were included if they quantified the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions that had any of the following complications: mortality, a near-miss event, haemorrhage, sepsis, injury and anaemia. We calculated summary measures of the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with each complication by conducting meta-analysis and explored whether these have changed over time.

Results

Based on data collected between 1988 and 2014 from 70 studies from 28 countries, we estimate that at least 9% of abortion-related hospital admissions have a near-miss event and approximately 1.5% ends in a death. Haemorrhage was the most common complication reported; the pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with severe haemorrhage was 23%, with around 9% having near-miss haemorrhage reported. There was strong evidence for between-study heterogeneity across most outcomes.

Conclusions

In spite of the challenges on how near miss morbidity has been defined and measured in the included studies, our results suggest that a substantial percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions have potentially life-threatening complications. Estimates that are more reliable will only be obtained with increased use of standard definitions such as the WHO near-miss criteria and/or better reporting of clinical criteria applied in studies.

Keywords: maternal health, systematic review

Key questions.

What is already known?

It was recently estimated that 25 million women sought an unsafe abortion in 2014. By defining and accurately measuring abortion-related morbidity, we can start to tease out the spectrum of risk associated with unsafe abortion.

In a previous systematic review, including literature published until July 2010, Alder and colleagues estimated that the median prevalence of severe complications ranged from 1.6% for renal failure to 7.2% for severe trauma, with a median case fatality of 3.3% among women who had postabortion complications in areas with limited access to abortion.

What are the new findings?

This systematic review identified 35 studies reporting on the complications among abortion-related hospital admissions published since the end date of the search strategy used by Adler et al, giving a total of 70 studies when added to those identified by the previous review. We identify that a substantial percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions have potentially life-threatening complications, with no improvement noted in the percentage of abortion-related complications with these extremely severe outcomes over time.

What do the new findings imply?

The finding that a high percentage of women seeking postabortion care experience life-threatening complications underlines the importance of ensuring access to safe abortion to prevent complications and of providing high-quality care for complications when they do occur.

Introduction

Unsafe abortion remains a considerable public health problem, with the most recent global incidence estimates suggesting 25.1 million women had undergone an ‘unsafe’ abortion annually between 2010 and 2014.1 The WHO considers an abortion to be safe if it is provided with a safe, WHO recommended method and by a trained person.1 What constitutes a safe method or a trained person has evolved over time with changes in evidence-based guidelines, including with respect to the role of non-physician healthcare providers.2 A particularly major shift in recent years has been increased access to and use of medical abortion, with potential for access for self-use especially in areas where abortion services are extremely restricted or illegal.3 4

Complexities in the legal and healthcare environment mean that abortions cannot simply be categorised as either safe or unsafe. The WHO now uses three categories, safe, less safe and least safe abortions,1 which represent a gradient of risk depending on factors including abortion method, provider and gestational age. By defining and accurately measuring abortion-related morbidity, we can start to tease out the spectrum of risk associated with unsafe abortion. At the extreme end, the adverse health outcomes of an unsafe abortion can include mortality and near-miss morbidity (complications which would have most likely resulted in death had the woman not made it to hospital).5

A systematic review published in 2012 attempted to quantify the severity of abortion-related complications.6 Based on data from 43 studies, Adler and colleagues estimated that the median prevalence of severe complications ranged from 1.6% for renal failure to 7.2% for severe trauma, with a median case fatality of 3.3% among women who had postabortion complications. The authors, however, also highlighted several methodological issues hindering their ability to combine results from the studies meaningfully, including substantial between-study heterogeneity.

This paper provides a timely update of the review by Adler and colleagues, given the change in the landscape of abortion services, notably the increased availability of medical abortion in many settings and greater access to safer surgical abortion care and the increasing awareness that understanding the safety of abortion requires better data on morbidity.7 The objective of this review is to update the systematic review by Adler et al, identifying studies quantifying the complications associated with abortions in regions where access to abortion is limited, and to provide estimates of the magnitude and severity of complications associated with abortion with a particular focus on potentially life-threatening complications, including near-miss morbidity and mortality. Unlike the previous review, we also examine potential sources of between-study heterogeneity in estimates of abortion-related severe morbidity and mortality using meta-regression and explore how complications of abortion have changed over time.

Methods

Search strategy

A review protocol outlining the methods for our systematic review was developed (available on request from corresponding author). We included most studies identified in the review by Adler et al,6 covering literature published up to 1 July 2010. Eight studies from the Adler et al review were not included in this review due to stricter inclusion criteria (further details below). To identify studies published since July 2010, the search strategy developed by Adler et al was used to search Medline, Embase, Popline and two of the WHO regional databases (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) and African Index Medicus (AIM)) from January 2010 to July 2016. For Medline and Embase, the search identified articles where their abstract, title or keywords contained an abortion term and a term related to a comprehensive list of morbidities or mortality. For the simpler databases—Popline and LILACS—a simplified search was conducted, including all studies referring to abortion and reference to at least one of a simple list of complications. For AIM, all articles referring to abortion were included. The search strategy is available in the online Supplementary appendix 1. Additional publications were identified by manually searching the reference lists of included articles.

bmjgh-2017-000692supp001.docx (728.4KB, docx)

Study selection

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy were exported into EndNote (2010–2013) or EPPI-reviewer (2014–2016) and two authors out of three (CC, FY and OO) screened each abstract. Where there was disagreement, the two authors discussed the abstract to decide whether it should be included for full-text review. One author reviewed each of the full texts identified as potentially relevant at the abstract screening stage for inclusion in the review (CC and FY).

Studies were included if they reported a breakdown of the complications of hospital-related abortion admissions in a sample of at least 30 women, in a setting where there is limited access to abortion services. Settings with ‘limited access to abortion’ were defined in line with Adler et al where countries were classified ‘based on the WHO estimates of the numbers of complications dues to abortions’.6 Studies from the following WHO regions were excluded, as the burden of unsafe abortion is ‘negligible’: AMRO A, EURO A and WPRO A.8 Trials assessing the effectiveness of different methods of abortion were also excluded as it was assumed that the abortions would be safe under trial conditions. Due to the poor validity of self-report of complications, studies were excluded if they relied on self-report of complications.9 10 Studies were excluded if they did not provide a measure of the number of abortion-related hospital admissions or only looked at a subgroup of abortion-related hospital admissions (eg, septic abortions only or only women admitted to an intensive care unit). This final exclusion criteria was not applied in the study by Adler et al.6

Data extraction

Data from all relevant studies were extracted by a single author (CC or FY) into an extraction form developed in Excel, with extraction double-checked by a second author (CC or FY). Articles included in the review by Adler et al6 were re-extracted to ensure that consistent decisions were made with respect to the classification of the complications of unsafe abortion. Basic descriptive information for each study was extracted on the study design and the study population. For the study population, we categorised the types of abortion included in the study sample as follows: ‘all’ abortions, spontaneous and induced abortions or only induced abortions. Where results were presented stratified by the type of abortion, we added together estimates to give the total number of complications across induced and spontaneous abortions, due to the challenges in identifying induced abortions only.11 The gestational age of the study sample was noted where reported.

Data were extracted for each study on the number of abortion-related hospital admissions and the definition and number of abortion-related hospital admissions with the following outcomes: severe complications (as defined by authors); near-miss events defined as ‘a woman who nearly died but survived a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy’5 12 and; mortality. Data were also extracted on the number of women with abortion who had the following complications: haemorrhage, infection, injury (injury to the cervix or vaginal area or uterine perforation) and anaemia. For these complications, we extracted information on each complication according to whether the definition in the study could be classified as ‘near miss’, ‘severe’ or ‘not severe/unspecified’. Further details of this classification are provided in the online Supplementary table 1 (online Supplementary appendix 2).

For studies that did not report the total number of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss, but did provide some individual criterion of complications or organ dysfunction that could be categorised as near miss, we calculated a minimum estimate for the number abortion-related hospital admissions with a near-miss event. Two different methods were used depending on the type of data available in the study:

For studies where each abortion-related hospital admission was assigned to only one complication, categories of complications which could be considered near miss were added together to give an estimate of the number of near miss cases.

For studies where each abortion-related hospital admission could be assigned to multiple conditions, we selected only one criterion that could be considered near miss (in most cases shock).

Where data were presented in the study stratified by the method of abortion, we extracted an estimate of the complications associated with abortions induced using misoprostol (as self-reported or suspected by the healthcare provider). Similarly, we extracted estimates stratified by gestational age where available.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The risk of bias was determined using the component approach outlined by The Cochrane Collaboration for a number of predefined quality criteria. All studies were assessed as at high or low risk of bias on the following criteria:

Representativeness of the study population—high risk of bias if studies were not representative of a clearly defined geographical region (eg, a district).

Completeness of case ascertainment—high risk of bias if records were only examined from one or two hospital departments (eg, Obstetrics and Gynaecology department), rather than all departments of the facility which may admit women with abortion complications.

Quality of complication diagnosis—high risk of bias if this was done retrospectively, rather than prospectively.

If a study did not contain sufficient information to classify it as at either high or low risk, it was classified as at unclear risk of bias.

Data synthesis and analysis

For each study, we calculated the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions attributable to: near miss (overall, due to haemorrhage, sepsis, injury and anaemia); severe complications (overall, haemorrhage, sepsis and anaemia); not severe/unspecified complications (haemorrhage, sepsis, injury and anaemia) and death. Some studies did not report on whether any deaths were observed among the hospital-related abortion admissions, most likely because there were no deaths. We therefore assumed that mortality was 0% in these studies for our overall estimate of case fatality, but conducted sensitivity analyses removing these studies to see how this influenced our estimate. Excluding studies with no deaths reported provides a ceiling estimate of case fatality.

For near miss and mortality, pooled estimates of the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions that had each outcome were calculated using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects method in R V.3.4.1.13 These pooled estimates were stratified by median year in which the study was conducted: an early period (1990–1995) when misoprostol was unlikely to be widely available; a mid-period (1996–2008) when misoprostol was being rolled out in many settings and a late period (2009–2013) when misoprostol was likely to be available in many settings. The percentage of the variation between study estimates which was due to between-study differences, rather than chance, was calculated in the form of the I2 statistic.14 Using median year of study as a study-level measure of the time period in which the study was conducted will be less reliable for studies spanning long time periods. We therefore conducted a sensitivity analysis of the pooled estimates by median year of study, removing any studies longer than 5 years.

In STATA V.15.0, meta-regression was subsequently used to explore study-level factors which may be associated with between-study heterogeneity (region, definition of abortion, median year of data collection and whether the study was conducted in a non-population representative sample of facilities or in facilities that were representative at the district or national level) for both case fatality and near miss. For estimates of the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions that were near miss, we also explored the method used to calculate the number of near miss abortion-related hospitals admissions as a source of between-study heterogeneity. This was divided into three groups as follows: (1) authors provided estimate of near miss; (2) we added categories of complications which could be considered near miss and (3) we used the single largest reported near miss event for a minimum estimate.

To explore whether the composition of complications among abortion-related hospital admissions has changed over time, pooled estimates of the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions attributable to each cause (haemorrhage, sepsis, injury and anaemia) was calculated using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects method, stratified by severity of the complication and by the median year of study (as described above).

Results

Search strategy results

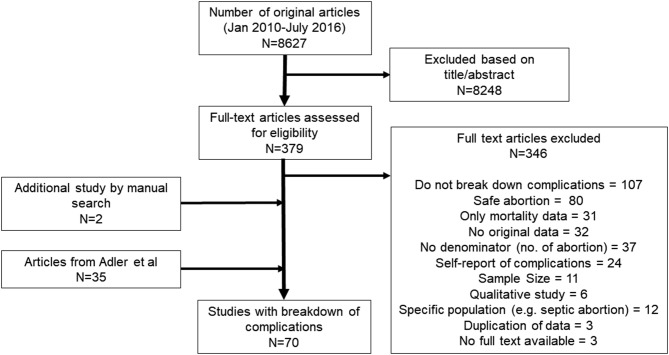

As shown in figure 1, 8627 titles and abstracts were identified for review from the search strategy from 2010 to July 2016. Of these titles and abstracts, 379 were identified as potentially useful and full texts were sought. Only three full texts could not be located. Thirty-three of the reviewed full texts met the inclusion criteria, with most studies being excluded for not providing information on the complications of abortion (n=107) or for only including safe abortions (n=80). Two additional articles were identified by manually searching the reference list of included articles, resulting in 35 relevant studies for July 2010–July 2016. Combining these recent studies with those identified in the earlier review gave 70 studies. Four studies provided estimates of complications among abortion-related hospital admissions by misoprostol versus other methods,15–18 and 10 studies stratified estimates by gestational age.15 16 19–26

Figure 1.

Search process for selection of papers.

Study characteristics

The online Supplementary table 2 describes the 70 studies, of which 39 were from Africa, 22 from Asia and nine from Latin America. The time during which data were collected varied considerably between studies. The earliest data come from 1988, with the median year of data collection in 1990–1995 for 12 studies, in 1996–2008 for 33 studies and from 2009 to 2013 for 21 studies. Four studies did not provide information on when data were collected and were grouped separately for all analyses by time period. Three studies had data collected which spanned more than 5 years27–29; although for one of these studies, it was possible to extract data for a shorter period of time.29

The overall risk of bias of the studies is shown in the online Supplementary figure 1. Only 10 of the studies described sampling facilities that were representative at the district or national level (14.3%). Most studies included women from only a single facility (n=43, 61.4%), with nine studies recruiting from between two and five facilities (12.9%) and seven studies recruiting from more than five facilities (10.0%). One study provided no details on how women were identified. Most studies did not provide sufficient detail to allow us to assess whether all cases of abortion in a facility were likely to be included (n=38, 54.3%), while four studies were classified at low risk of bias for missing cases of abortion (5.7%), as they described collecting data for all or most hospital departments. The remaining 28 studies only look at cases within certain departments of the facility (40.0%), largely the obstetrics and gynaecology department. Finally, 26 studies were conducted retrospectively (37.1%), 43 prospectively (61.4%) and one did not provide information to assess this (1.4%).

Thirteen studies reported both spontaneous and induced abortion (18.6%); 41 reported only induced abortion (58.6%) and 16 did not specify abortion type and/or stated all abortions were included (22.9%). Further details on the definition of ‘abortion-related hospital admissions’ for each study can be found in the online Supplementary table 3.

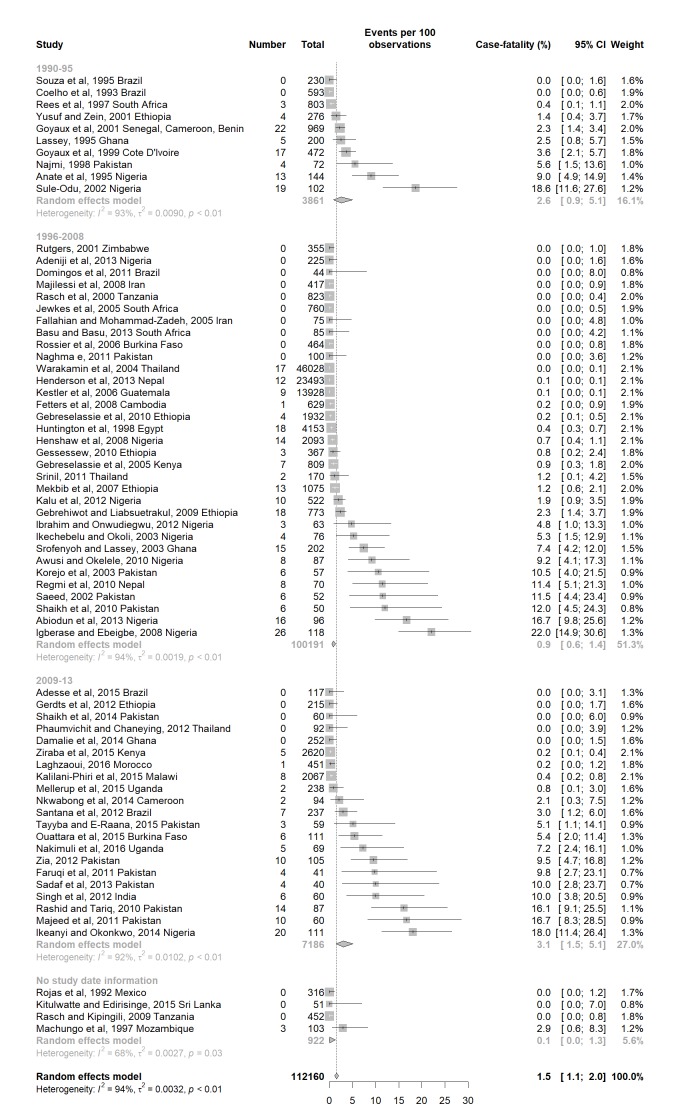

Mortality among abortion-related hospital admissions

The estimates of case fatality among abortion-related hospital admissions ranged from 0% to 22.0% across 68 studies either explicitly reporting case fatality or not mentioning any deaths in the study population in which case we assumed case fatality to be 0% (online Supplementary table 3). As shown in figure 2, the overall pooled case fatality was 1.5% (95% CI: 1.1 to 2.0). There was no evidence for a difference between case fatality among studies conducted in the early period (pooled case fatality=2.6%, 95% CI 0.9 to 5.1) compared with studies from the most recent time period (pooled case fatality=3.1%, 95% CI 1.5 to 5.1). There was strong evidence for between-study heterogeneity across all pooled estimates of case fatality. As shown in the online Supplementary table 4, there was little influence of the studies that spanned more than 5 years of data collection. Exclusion of studies that did not mention whether there were any deaths in the study population, increased our overall estimate of case fatality from 1.5% to 2.4% (95% CI 1.8 to 3.0) and led to increased estimates across each time period (online Supplementary table 4 and online Supplementary figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the percentage of women with abortion-related hospital admissions who died.

In univariate meta-regression of the 68 studies of case fatality, there was evidence that type of abortion (p=0.005), region (p=0.03) and inclusiveness of the sampling strategy (p=0.03) influenced the between study variation in case fatality (table 1). In the multivariable meta-regression model, only type of abortion (induced or spontaneous) remained independently associated with case fatality (p=0.005). Studies of only induced abortions had, on average, higher case fatality than studies that included women with all types of abortion or did not explicitly state the type of abortions included.

Table 1.

Meta-regression for case fatality and near-miss events among abortion-related hospital admissions

| Outcome and study group | Number of studies | % with outcome (95% CI) |

Crude OR (95% CI) | P values | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | P values* |

| Case fatality | Adjusted R2=12.5% | |||||

| Median year of study | ||||||

| 1990–1995 | 10 | 2.6 (0.9–5.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1996–2008 | 33 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.41 (0.06 to 2.68) | 0.76 (0.12 to 4.61) | ||

| 2009–2013 | 21 | 3.1 (1.5–5.1) | 1.17 (0.16 to 8.56) | 0.31 | 1.63 (0.25 to 10.79) | 0.56 |

| Type of abortion | ||||||

| All/unspecified abortion | 16 | 0.2 (0–0.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Spontaneous+induced | 11 | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 1.73 (0.25 to 11.88) | 1.73 (0.25 to 11.88) | ||

| Induced only | 41 | 4.1 (2.5–6.1) | 9.68 (2.27 to 41.27) | 0.005 | 9.68 (2.27 to 41.27) | 0.005 |

| Region | ||||||

| Africa | 39 | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Asia | 22 | 2.1 (1.3–3.1) | 1.62 (0.42 to 6.21) | 1.05 (0.27 to 4.05) | ||

| Latin America | 7 | 0 (0–0.5) | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.66) | 0.03 | 0.16 (0.02 to 1.52) | 0.26 |

| Sampling strategy | ||||||

| Facility | 54 | 2.7 (1.9–3.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Population | 10 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.14 (0.02 to 0.81) | 0.03 | 0.22 (0.03 to 1.83) | 0.16 |

| Near miss | Adjusted R2=23.9% | |||||

| Median year of study | ||||||

| 1990–1995 | 6 | 5.7 (2.2–10.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1996–2008 | 27 | 6.6 (4.3–9.3) | 1.55 (0.56 to 4.31) | 1.16 (0.36 to 3.71) | ||

| 2009–2013 | 14 | 18.3 (9.6–29.1) | 5.09 (1.63 to 15.89) | 0.007 | 2.76 (0.79 to 9.65) | 0.08 |

| Type of abortion | ||||||

| All/unspecified abortion | 10 | 9.4 (3.9–16.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Spontaneous+induced | 8 | 4.0 (2.3–6.1) | 0.61 (0.17 to 2.22) | 0.86 (0.25 to 2.94) | ||

| Induced only | 30 | 10.7 (7.5–14.3) | 1.64 (0.61 to 4.42) | 0.17 | 1.73 (0.67 to 4.49) | 0.24 |

| Region | ||||||

| Africa | 25 | 7.9 (5.4–10.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Asia | 19 | 12.6 (6.9–19.5) | 1.53 (0.67 to 3.47) | 1.01 (0.47 to 2.14) | ||

| Latin America | 4 | 3.2 (0.4–8.5) | 0.32 (0.08 to 1.39) | 0.11 | 0.18 (0.03 to 1.32) | 0.23 |

| Sampling strategy | ||||||

| Facility | 40 | 10.7 (7.5–14.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Population | 8 | 3.2 (2.0–4.5) | 0.35 (0.12 to 0.97) | 0.05 | 0.47 (0.19 to 1.19) | 0.11 |

| Method of calculating near miss | ||||||

| WHO or other near-miss criteria | 3 | 26.6 (9.1–49.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Addition of near miss due to complications | 11 | 17.2 (6.6–31.3) | 0.49 (0.10 to 2.48) | 0.65 (0.14 to 3.14) | ||

| Single near-miss criterion | 34 | 5.7 (4.0–7.5) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.64) | 0.003 | 0.23 (0.05 to 0.99) | 0.02 |

*Case fatality model adjusted for type of abortion. Near-miss events model adjusted for method of calculating near-miss cases and for median year of study.

Only one study reported case fatality by abortion method, with only two deaths reported among women where the method of abortion was ‘not known’.16 Six studies provided estimates of case fatality by gestational age,19 20 22–25 and in all studies the case fatality was higher at later gestation (online Supplementary table 3).

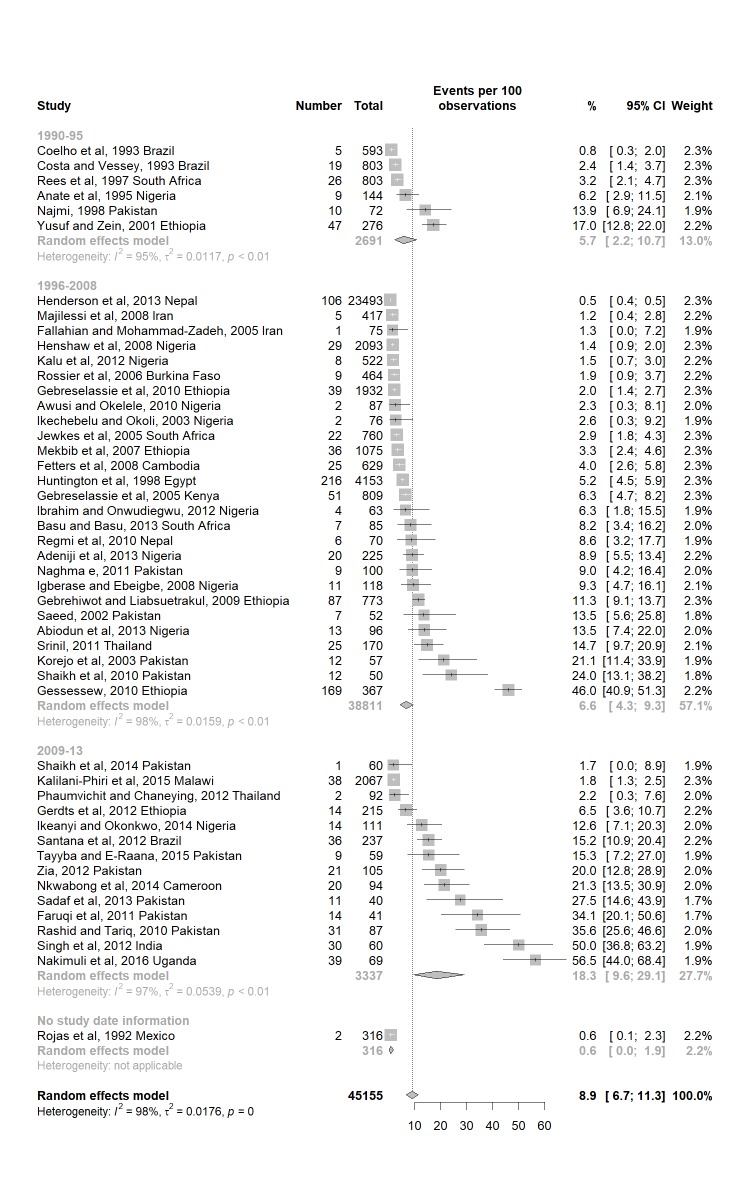

Near miss among abortion-related hospital admissions

As shown in the online Supplementary table 3, 48 studies provided estimates of the percentage of abortions that were near miss, although only three of these used near miss criteria to do so (two used WHO criteria, while the third defined the outcome as any of acute renal failure, severe haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion, hypovolemic shock, sepsis with or without shock or disseminated intravascular coagulation). For 14 studies, we calculated the total number of near-miss events by summing all near miss complications, as only a single complication meeting the near miss criteria was presented for each abortion-related hospital admission. The remaining 32 studies reported multiple complications per abortion so we only included a single near miss complication that accounted for the largest number of abortion-related hospital admissions. The percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions classified as having a near miss event ranged from 0.5% to 56.5% across the studies. Estimates from only the three studies that used near miss criteria ranged from 14.7% to 56.5%. The pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss events, overall and stratified by time, is shown in figure 3. Overall, 8.9% of abortion-related hospital admissions were estimated to have near miss morbidity (95% CI: 6.7 to 11.3). The estimates from studies in the early period had a pooled percentage of 5.7% (95% CI: 2.2 to 10.7) compared with 18.3% among studies in the late period (95% CI: 9.6 to 29.1). There was, however, strong evidence of between study heterogeneity in all time periods (I2 ≥95%, P<0.001). The sensitivity analysis, removing the estimates that spanned more than 5 years, did not change the results appreciably (online supplementary table 5).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with a near miss complication.

In the univariate meta-regression, there was evidence that time period (P=0.007) and method of calculating near miss (p=0.003) influenced the between-study variation in the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions which with near miss morbidity (table 1). In the multivariate meta-regression model, both time period (P=0.08) and method of calculating near miss (P=0.02), remained independently associated with the percentage of near miss events among abortion-related hospital admissions. Studies where the median year of data collection was more recent (2009–2013) had, on average, a higher percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss, compared with studies in the early time period. Studies where only a single near miss criterion was used to estimate the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions that were near miss had the lowest percentage attributable to near miss, whereas studies using near miss criteria had the highest percentage. After adjusting for time period and method of calculating near miss, there was no evidence that type of abortion (P=0.24), region (P=0.23) or population (P=0.11) were associated with the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss.

It was possible to estimate the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with a near miss event separately for abortions induced with misoprostol for three studies, and we do see a lower risk of near miss events in this group. However, differences in the methods used by women who did not take misoprostol between the studies makes it difficult to compare across the studies.16–18 Of the four studies where estimates of the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions which had near miss complications could be stratified by gestational age,16 19 23 26 three studies reported the percentage to be higher among abortions at a later gestational age16 19 23 (online Supplementary table 2).

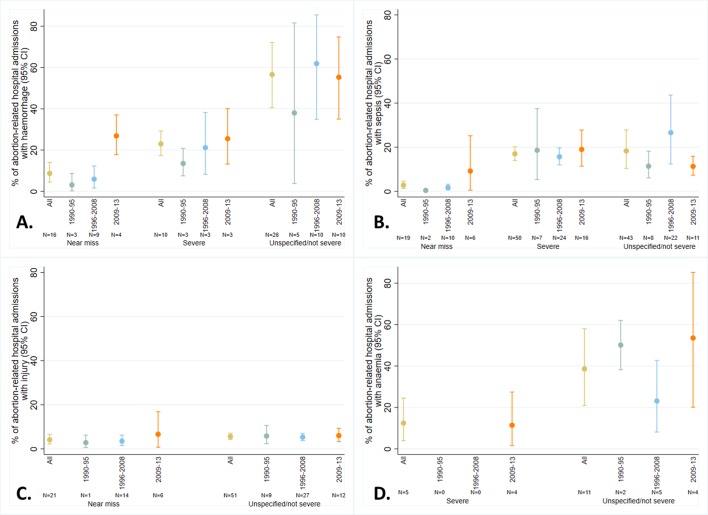

Cause-specific complications among abortion-related hospital admissions

Haemorrhage

The online Supplementary table 6 provides study-specific definitions and estimates for studies that report the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions which had complications classified as due to haemorrhage. Overall, 26 studies provided an estimate of unspecified or not severe haemorrhage, with 10 studies providing estimates for severe haemorrhage and 16 for near miss haemorrhage. The pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with complications of non-severe or unspecified haemorrhage was 56.6% (95% CI 40.5 to 72.1, I2=100%). For severe haemorrhage, the pooled percentage was 23.0% (95% CI 17.3 to 29.3, I2=97%). The pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss haemorrhage was 8.7% (95% CI 4.5 to 16.0.4, I2=99%).

As shown in figure 4A, the pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with complications related to near miss due to haemorrhage is substantially lower across studies with a median year of data collection between 1990 and 1995 (pooled percentage=3.1%, 95% CI 0.2 to 8.7) compared with those from 2009 to 2013 (pooled percentage=26.9%, 95% CI 17.8 to 37.0). A similar trend is observed for severe haemorrhage and unspecified/non-severe haemorrhage but estimates between the different time periods are consistent within CIs.

Figure 4.

Pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with (A) haemorrhage, (B) sepsis, (C) injury and (D) anaemia. All estimates are stratified by severity of the complication and time period.

Sepsis

Forty-three studies reported the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with non-severe or unspecified infection; 50 reported on severe infection and 19 reported near miss due to infections (study specific definitions and estimates given in the online Supplementary table 7). The pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with complications attributable to unspecified or not severe infection was 18.3% (95% CI 10.4 to 27.7, I2=100%). For severe infection, the pooled percentage was slightly lower (17.0%, 95% CI 14.0 to 20.2, I2=99%) and for near miss infection, the pooled percentage was much lower (2.8%, 95% CI 1.3 to 4.6, I2=93%).

Studies with a median data collection year in the early period had lower pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss infection than studies with a median year of data collection in most recent time period (0.4% vs 9.2%) (figure 4B); however, the estimate for the early period is based on only two studies, and the CI for the pooled percentage in the most recent time period is very wide. No difference in the pooled percentage by year of data collection was observed for severe infection or for unspecified/non-severe infection.

Injury

As shown in the online Supplementary table 8, 51 studies reported on the percentage of abortion complications due to non-severe or unspecified injuries and 21 studies reported on near miss due to injuries. The pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with non-severe or unspecified injury was 5.6% (95% CI 4.2 to 7.1, I2=98%). There was no evidence that pooled percentage changed by median year of study (figure 4C).

For near miss due to injuries, we estimated a pooled percentage of 4.1% (95% CI 2.2 to 6.6, I2=95%). As illustrated in figure 4C, the pooled percentage for studies with a median year of data collection in the most recent period was higher than for studies with earlier median data collection dates, but the CIs were very wide and consistent with the pooled estimates from the other time periods.

Anaemia

Only five studies reported on the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with severe anaemia, and all these studies had a median year of data collection in the most recent time period (online Supplementary table 9), with the exception of one study which did not provide study dates. We estimated a pooled percentage of 12.4% (95% CI 3.9 to 24.5, I2=91%) across the five studies.

Eleven studies provided estimates for non-severe or unspecified anaemia (online Supplementary table 9), with study estimates ranging from 4.3% up to 77.0% of abortion-related hospital admissions. Overall, there was a pooled percentage of 38.6% (95% CI 20.9 to 58.0, I2=99%), with no evidence that this has changed over time (figure 4D).

Discussion

This systematic review provides a timely update on the type and severity of complications of abortions where access to abortion is limited. Based on data from 70 studies from 28 countries where access to abortion is limited, we estimate that at least 9% of abortion-related hospital admissions have near miss complications and approximately 1.5% ends in a death. The case fatality was lower than that reported by Adler and colleagues, most likely due to differences in the way the study estimates were pooled in the two different reviews.6 Consistent with the clinical literature, bleeding and infection were common complications among abortion-related hospitalisations, and we note high levels of anaemia which is likely to be linked to haemorrhage. Overall, there was higher prevalence of haemorrhage than sepsis with 9% of abortion-related hospital admissions experiencing near-miss cases due to haemorrhage, while 57% had non-severe or unspecified haemorrhage. Near-miss cases due to sepsis accounted for 3% of abortion-related complications, while non-severe or unspecified sepsis accounted for 18% of these admissions.

Our comparison of pooled estimates from studies with a median year of data collection between 1990 and 1995 and those with a median year of 2009–2013 suggest that the percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with extremely severe complications has increased, while case fatality has stayed relatively consistent. Even after accounting for some of the methodological differences between the studies using meta-regression, we still found evidence for an increase in the percentage of abortion-related hospitals admissions with near-miss complications. A nationally representative study conducted in Ethiopia, published since our search was conducted, also documented an increase in the number of women seeking post abortion care with severe abortion morbidity from 2008 to 2014 of 7%–11%.30 We also have some surprising complication-specific results with, for example, the pooled percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions with near miss due to sepsis increasing from 0.4% in studies conducted in the early period, compared with 9% in the most recent studies. Pooled estimates of near miss due to haemorrhage also showed a dramatic increase over time from 3% to 27%. These results do need to be interpreted with caution, as some pooled estimates are made based only on a few studies.

It is likely that improvements in measurement and recording over time have contributed, at least in part, to the patterns we observe. As, for example, researchers and hospital staff have become more aware of the near miss definition, cases of near miss due to abortion are more likely to be recorded and therefore counted in our estimates. It is, however, also plausible that there has been an increase in the percentage of abortion-related complications treated in health facilities that are near miss. There may have been an absolute decrease in the number of women with less severe abortion-related complications coming to the hospital because they are seeking care in lower-level facilities. This would mean that the severe complications account for a larger percentage of all abortion-related hospital admissions. Alternatively, decreasing stigma or fear of being prosecuted in some areas and/or increasing availability of postabortion care in facilities, may mean more women who have severe abortion-related complications are coming to hospital for treatment. If this is the case, we would expect that abortion-related mortality is decreasing in the community. A final possible explanation is that as fertility declines across many settings, women who wish to reduce their fertility but have unmet need for contraception either due to financial barriers or due to concerns about side effects, instead seek out unsafe abortions, which may in turn increase the severity of the abortion complications observed within facilities. This final pathway, however, is not well documented in the literature.

Very high heterogeneity between the study estimates, across almost every pooled estimate we calculated, means our results must be interpreted with caution. This is not surprising given the observational nature of the data, and the differences between the studies with respect to the type of abortions included, the study design and the variations in the definitions of some of the complications. Meta-regression analysis of near miss and case fatality estimates enabled us to explore the influence of methodological differences between studies. It is clear that some of the difference between studies are driven by study level factors, particularly the definition of hospital-related abortion admissions and, for near miss, the way in which we calculated an estimate of near miss cases for each study, which is in turn related to the quality of reporting. We see that studies which only look at induced abortion have higher case fatality than studies also including spontaneous abortions. Complications are more likely after an induced than a spontaneous abortion, but the vastly increased case fatality rate in these studies may also be driven by a hospital-related abortion admission being more likely to be classified as an induced abortion from the severity of the complication.

Another important limitation was in the study quality, and as with all reviews, the summary estimates from this systematic review are only as good as the data on which they are based. The risk of bias assessment indicated that most studies were at high risk of bias in at least one of the domains. We have particular concerns over our estimates of near miss complications due to the lack of studies explicitly defining complications in line with well establish near miss criteria. Further, for many studies, we could only estimate a minimum number of cases that were near miss by selecting the single largest complication that fitted the near miss definition. This will undoubtedly be an underestimate of the true number of women who near miss complications in these studies.

As access to misoprostol increases, and more abortions are self-induced with this method, it should lead to rarer abortion-related mortality at the population level. Understanding women’s care needs remains important and measuring morbidity as a heath outcome measure will continue play a crucial part in this.31 The availability of a standardised definition and tools for measuring maternal near miss by WHO in 2009 was a welcome development to standardise the abortion near miss data collected from different contexts.5 31 However, these criteria and tools may need to be refined for abortion and for low-income and middle-income settings.32 33 Future facility-based research studies should use standard definitions such as the WHO near miss consistently and/or clearly define the clinical criteria applied in their studies, ideally collecting this data prospectively and stratifying results by gestational age, method of inducing abortion and the abortion provider information. There should also be a push to collect data from population-representative samples of facilities to understand admission patterns at the population level and generate trends in safety over time. By only focussing on hospital admissions, we have not quantified the full spectrum of risk associated with unsafe abortion. As self-use of medical abortion continues to expand, it will be is necessary to increase and improve representative community-level data collection on abortion care seeking and outcomes.

In spite of the challenges on how near miss morbidity has been defined and measured in the included studies, our results suggest that a substantial percentage of abortion-related hospital admissions have potentially life-threatening complications, highlighting the importance of providing high-quality postabortion care. Ultimately, health outcomes are essential indicators to assert progress in healthcare services. Any reproductive health programme that aims at the local level to reduce maternal deaths from unwanted or unplanned pregnancies benefits from good measurement of health outcomes, including severe morbidity. Given the hidden nature of abortion and the stigma associated with it, health outcomes such as near miss that can be measured meaningfully in health facilities should be particularly useful for evaluation and monitoring.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: VF, BG and ӦT initiated the study and defined the initial research question. CC, OOO and FY developed the detailed methodology and carried out the literature review. CC drafted the protocol, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. VF reviewed any doubtful papers. AJA assisted with the integration of data from the previous systematic review. FY and RP helped with the extraction of clinical data from included studies. All other authors critically reviewed the draft and approved the final version for publication.

Funding: This work was primarily funded by the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored program executed by the World Health Organization (WHO). We also acknowledge the support from the Strengthening Evidence for Programming on Unintended Pregnancy (STEP UP) funded by the Department for International Development (DFID) which co-funded VF and OO’s time for this review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. The Lancet 2017;390:2372–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganatra B, Tunçalp Ö, Johnston HB, et al. From concept to measurement: operationalizing WHO’s definition of unsafe abortion. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:155 10.2471/BLT.14.136333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harper CC, Blanchard K, Grossman D, et al. Reducing maternal mortality due to elective abortion: potential impact of misoprostol in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007;98:66–9. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Winikoff B, Sheldon W. Use of medicines changing the face of abortion. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2012;38:164–6. 10.1363/3816412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Say L, Souza JP, Pattinson RC. Maternal near miss--towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009;23:287–96. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adler AJ, Filippi V, Thomas SL, et al. Quantifying the global burden of morbidity due to unsafe abortion: magnitude in hospital-based studies and methodological issues. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;118(Suppl 2):S65–77. 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sedgh G, Filippi V, Owolabi OO, et al. Insights from an expert group meeting on the definition and measurement of unsafe abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;134:104–6. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Sixth edn Geneva: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ronsmans C, Achadi E, Cohen S, et al. Women’s recall of obstetric complications in south Kalimantan, Indonesia. Stud Fam Plann 1997;28:203–14. 10.2307/2137888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seoane G, Castrillo M, O’Rourke K. A validation study of maternal self reports of obstetrical complications: implications for health surveys. Int J Gynecol Obstet 1998;62:229–36. 10.1016/S0020-7292(98)00104-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fetters T. Prospective approach to measuring abortion-related morbidity: individual-level data on postabortion patients. Methodologies for estimating abortion incidence and abortion-related morbidity: a review. New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2010:135–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adler AJ, Filippi V, Thomas SL, et al. Incidence of severe acute maternal morbidity associated with abortion: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:177–90. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Damalie FJ, Dassah ET, Morhe ES, et al. Severe morbidities associated with induced abortions among misoprostol users and non-users in a tertiary public hospital in Ghana. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:90 10.1186/1472-6874-14-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Srinil S. Factors associated with severe complications in unsafe abortion. J Med Assoc Thai 2011;94:408–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coêlho HL, Teixeira AC, Santos AP, et al. Misoprostol and illegal abortion in Fortaleza, Brazil. Lancet 1993;341:1261–3. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91157-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Costa SH, Vessey MP. Misoprostol and illegal abortion in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Lancet 1993;341:1258–61. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91156-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nkwabong E, Mbu RE, Fomulu JN. How risky are second trimester clandestine abortions in Cameroon: a retrospective descriptive study. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:108 10.1186/1472-6874-14-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gebrehiwot Y, Liabsuetrakul T. Trends of abortion complications in a transition of abortion law revisions in Ethiopia. J Public Health 2009;31:81–7. 10.1093/pubmed/fdn068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ziraba AK, Izugbara C, Levandowski BA, et al. Unsafe abortion in Kenya: a cross-sectional study of abortion complication severity and associated factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:34 10.1186/s12884-015-0459-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gebreselassie H, Gallo MF, Monyo A, et al. The magnitude of abortion complications in Kenya. BJOG 2005;112:1229–35. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anate M, Awoyemi O, Oyawoye O, et al. Procured abortion in Ilorin, Nigeria. East Afr Med J 1995;72:386–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goyaux N, Alihonou E, Diadhiou F, et al. Complications of induced abortion and miscarriage in three African countries: a hospital-based study among WHO collaborating centers. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:568–73. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2001.080006568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Majeed T, Saba K, Cheema AA, et al. Maternal mortality and induced abortion. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences 2011;5:480–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Santana DS, Cecatti JG, Parpinelli MA, et al. Severe maternal morbidity due to abortion prospectively identified in a surveillance network in Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;119:44–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sule-Odu AO, Olatunji AO, Akindele RA. Complicated induced abortion in Sagamu, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;22:58–61. 10.1080/01443610120101745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Igberase GO, Ebeigbe PN. Exploring the pattern of complications of induced abortion in a rural mission tertiary hospital in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Trop Doct 2008;38:146–8. 10.1258/td.2007.070096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henderson JT, Puri M, Blum M, et al. Effects of abortion legalization in Nepal, 2001-2010. PLoS One 2013;8:e64775 10.1371/journal.pone.0064775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gebrehiwot Y, Fetters T, Gebreselassie H, et al. Changes in morbidity and abortion care in ethiopia after legal reform: national results from 2008 and 2014. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2016;42:121–30. 10.1363/42e1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim CR, Tunçalp Ö, Ganatra B, et al. WHO Multi-Country survey on abortion-related morbidity and mortality in health facilities: study protocol. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000113 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tura AK, Stekelenburg J, Scherjon SA, et al. Adaptation of the WHO maternal near miss tool for use in sub-Saharan Africa: an International Delphi study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:445 10.1186/s12884-017-1640-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dragoman M, Sheldon WR, Qureshi Z, et al. Overview of abortion cases with severe maternal outcomes in the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health: a descriptive analysis. BJOG 2014;121(Suppl 1):25–31. 10.1111/1471-0528.12689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2017-000692supp001.docx (728.4KB, docx)