Abstract

Hypertensive cerebropathy is a pathological condition associated with cerebral edema and disruption of the blood–brain barrier. However, the molecular pathways leading to this condition remains obscure. We hypothesize that MMP-9 inhibition can help reducing blood pressure and endothelial disruption associated with hypertensive cerebropathy. Dahl salt-sensitive (Dahl/SS) and Lewis rats were fed with high-salt diet for 6 weeks and then treated without and with GM6001 (MMP inhibitor). Treatment of GM6001 (1.2 mg/kg body weight) was administered through intraperitoneal injections on alternate days for 4 weeks. GM6001 non-administered groups were given vehicle (0.9 % NaCl in water) treatment as control. Blood pressure was measured by tail-cuff method. The brain tissues were analyzed for oxidative/nitrosative stress, vascular MMP-9 expression, and tight junction proteins (TJPs). GM6001 treatment significantly reduced mean blood pressure in Dahl/SS rats which was significantly higher in vehicle-treated Dahl/SS rats. MMP-9 expression and activity was also considerably reduced in GM6001-treated Dahl/SS rats, which was otherwise notably increased in vehicle-treated Dahl/SS rats. Similarly MMP-9 expression in cerebral vessels of GM6001-treated Dahl/SS rats was also alleviated, as devised by immunohistochemistry analysis. Oxidative/nitrosative stress was significantly higher in vehicle-treated Dahl/SS rats as determined by biochemical estimations of malondialdehyde, nitrite, reactive oxygen species, and glutathione levels. RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry analysis further confirmed considerable alterations of TJPs in hypertensive rats. Interestingly, GM6001 treatment significantly ameliorated oxidative/nitrosative stress and TJPs, which suggest restoration of vascular integrity in Dahl/SS rats. These findings determined that pharmacological inhibition of MMP-9 in hypertensive Dahl-SS rats attenuate high blood pressure and hypertension-associated cerebrovascular pathology.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular, Hypertension, MMP-9, ROS

Introduction

Around 70 million American adults (29 %), 1 out of 3 individuals, suffer from hypertension. Hypertension is a major health problem, defined as high arterial blood pressure (>140 mmHg systolic and >80 mmHg diastolic) and a high risk factor for brain pathologies [1]. The relationship between dietary salt intake and the development of hypertension has been the subject of ongoing debate for decades [2, 3]. In the 1950s, study on large groups of Sprague–Dawley rats not only noticed positive and linear relationship between salt intake and blood pressure, but also observed marked individual-specific changes in blood pressure associated with salt intake [4]. Likewise, earlier reports also suggest the concept of heterogeneity of human blood pressure in response to alteration in dietary sodium intake [5]. Demographic, familial, genetic, and physiological factors have been found to play an important role in the development of salt-sensitive (SS) condition in hypertensive subjects [6]. Despite developing hypertension by excessive salt intake during SS condition, high salt intake with hypertension advances adversely to cerebrovascular pathologies; however, the associated pathogenic mechanisms remain obscure.

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is formed by specialized endothelial cells (ECs) and pericytes which in turn are surrounded by basal lamina, astrocytic end-feet, and perivascular interneurons [7]. The integrity of cerebral ECs is maintained through tight junctions (TJs) between ECs. The entire unit in essence sets effective physical barrier that selectively allows passage of required nourishment and prohibits pathogens that include potentially harmful small molecules circulating in the blood. TJs are comprised transmembrane proteins that include claudin, occludin, adhesion molecules, and cytoplasmic accessory proteins [8]. Claudins are one of the principal junctions that form dimers and interconnect ECs, while occludins restrict paracellular permeability and maintain electrical resistance across the barrier. Associated with transmembrane components, there are important accessory cytoplasmic proteins that include zona occludens (ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3). Zona occludens essentially performs dual function, by serving as recognition protein for TJ replacement and providing support to signal transduction proteins. Among all zona occludens, ZO-1 plays critical role in stabilizing and maintaining the functions of TJs that are frequently associated with barrier dysfunction [9]. Impairment in regulatory function of cerebral endothelial junction proteins can lead to BBB disruption but whether these regulatory junctions are affected under hypertensive condition is not well studied.

Chronic hypertension induces adaptive changes in cerebral arteries that lead to vascular alterations [10]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), zinc-dependent endoproteinases, play significant role in highly complex processes, including regulation of cell behavior and cell–cell communication [11, 12]. MMPs are induced under oxidative and vascular nitrosative stress and actively participate in the remodeling of cerebral blood vessels [13, 14]. MMPs are expressed in various cell types, including ECs, and are involved in various functions such as; subendothelial matrix (SEM) degradation, extracellular matrix (ECM) and vascular remodeling [15, 16]. We have previously shown the involvement of MMP-9 in cerebrovascular dysfunction [17, 18], by degrading the cerebral vasculature. Our lab including others clearly showed that MMP-9 attenuation can ameliorate cerebral pathologies [15, 18–20]. Although there is extensive literature on MMP-9 mediated cerebral pathologies, its role in hypertension-induced cerebrovascular pathologies is not explored much.

The association of hypertension with MMPs induction was studied that suggest the role of MMPs for the treatment of hypertension-induced cerebrovascular disruption. However, there are still several questions remain to be addressed. For example, how MMP attenuation can help blood pressure control and reverse some of the effects of hypertension on cerebral blood vessels? To address this, we designed the present study in a genetic rodent model of essential hypertension (Dahl salt-sensitive; Dahl/SS rats) and determined whether the pharmacological intervention could attenuate MMP-9, mitigate hypertension-, and hypertension-associated cerebrovascular dysfunction.

Animals and experimental design

The animal procedures were carefully reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), University of Louisville, in accordance with the animal care and proper guidelines of the National Institutes of Health. Eight-week-old male Dahl salt-sensitive (Dahl/SS) and Lewis rats were procured from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained on normal diet up to 6 months of age. After that the rats were fed on high-salt diet (4 %NaCl; Cincinnati Lab Supply, Cat. 5882 C-5A) for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks the animals were divided into four groups: 1. Dahl/SS rat group and 2. Lewis rat group was treated with vehicle (0.9 %w/v NaCl in water), and 3. Dahl/SS and 4. Lewis rat group was treated with Galardin (GM6001; a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor). The treatment was continued for 4 weeks [21].

GM6001 preparation GM6001 (Cat. No: CC1010, EMD Millipore, USA) was prepared in 0.9 % NaCl and given at a dose of 1.2 mg/kg body weight. GM6001 treatment was given on alternate days by intraperitoneal injections. The dose of GM6001 was based on an earlier study, where the agent was given by intraperitoneal injections [21].

Tail-cuff method (CODA; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) was used to determine blood pressure (BP) in different rat groups. Animals were acclimatized on a warming platform before BP measurements. Baseline BP was recorded before starting animals on high-salt diet and repeated every fortnight thereafter.

Rat brain tissue collection

At the end of treatment, animals were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital and brain samples were harvested. After washing with 50 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) brain samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

Estimation of biochemical parameters

Brain tissues from different rat groups were collected; homogenized in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4); and the levels of malondialdehyde, glutathione, nitrite, and thiosulfate were quantitated as described earlier [15, 22], with certain modifications. A brief description of the different tests is given below.

Measurement of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was assessed with the malondialdehyde (MDA) method using 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane as a standard. The homogenized brain tissues were treated with 0.3 ml trichloroacetic acid (TCA, 30 %), 0.3 ml thiobarbituric acid (2 %), and 0.15 ml 5 N hydrochloric acid. After that the samples were heated at 90 °C for 15 min and pink color of the reaction mixture was obtained. The samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and quantitated at 532 nm using a Spectra Max M2 plate reader (Molecular Device, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). MDA levels were expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein.

Measurement of glutathione

5,5-Dithiobis 2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) was used to assess the glutathione (GSH) level and reduced glutathione was used as a standard. An equal volume of 5 %TCA was added to the brain tissue homogenate and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and transferred to another tube. To the collected supernatant, 0.1 ml phosphate buffer (pH 8.4), DTNB, and 0.05 ml double distilled water was added. After 10 min the absorbance of the reaction mixture was recorded at 412 nm using a Spectra Max M2 plate reader (Molecular Device). The level of GSH was expressed in micrograms per milligram of protein.

Measurement of nitrite level

Nitrite level in the brain tissues was estimated using griess reagent [0.1 % N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 1 % sulfanilamide, and 2.5 % phosphoric acid] using sodium nitrite as a standard. Rat brain homogenates were centrifuged at 3, 000 rpm for 10 min and supernatant was transferred to the tube containing an equal amount of griess reagent. Afterwards, tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and the absorbance was recorded at 542 nm in a Spectra Max M2 plate reader (Molecular Device, USA). The level of nitrite was expressed in micrograms per milligram of protein.

Intracellular ROS estimation

Intracellular ROS was estimated fluorometrically using oxidation sensitive fluorescent probe 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) diacetate (Molecular Probes). Rat brain samples were used to prepare homogenates in HEPES–Tyrode solution (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and then treated with collagenase (750 unit/ml). The treatment was continued for 45 min at 37 °C. After enzymatic digestion, homogenous cellular population was collected through filtration and incubated with DCF (5 µM) for 15 min at 37 °C in water bath. After washing with HBSS (Hanks buffer saline salt), the cells were analyzed fluorometrically.

Gelatin zymography assay

Brain extracts (30 mg) were electrophoresed on 10 % sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel prepared with 2 % gelatin. The gels were then washed thrice with 2.5 % Triton X-100 (20 min each), and incubated for 24 h (37 °C) in activation buffer (5 mmol/L Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 0.005 % (v/v) Brij-35, and 1 mmol/L CaCl2). Gels were stained with coomassie dye and destained in order to monitor proteolytic activity of the sample as a clear band on a stained background. The images were recorded with gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA) and the data were analyzed with the Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Preparation of brain tissue extract and protein estimation

Rat brain tissues were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer containing PMSF (1 mM) and protease inhibitor cocktails (1 µl/ml of lysis buffer; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The extracts were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C until further use. Bradford dye was used to assess protein content in different samples as recommended by supplier’s protocol (Bio-Rad, USA).

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

Equal amounts of proteins (40 µg) from different experimental rat groups were loaded on a polyacrylamide gel and run at a constant current until the dye reached at the bottom. After transferring the separated proteins to the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes using an electrotransfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, USA), the membranes were blocked with 5 % non-fat dry milk (1 h) and probed overnight with a primary antibody [anti-MMP-9,] at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were further incubated with a secondary antibody [horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, Santa Cruz, CA, USA)] for 60 min at room temperature. The membranes were washed and developed with ECL Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The images were recorded in the chemi-program of a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA). After that, the membranes were stripped and re-probed for GAPDH with an anti-GAPDH antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Each band density was normalized with the respective GAPDH density using Image Lab densitometry software (Bio-Rad).

Reverse-transcriptase PCR

RT-PCR was performed to evaluate the mRNA transcript levels of the different genes. Total RNA from rat brain tissues were isolated with TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purity and quantity of RNA samples were assessed using nanodrop-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). 2 µg RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA as described in our previous publication [15]. Sequence-specific oligonucleotide primers were prepared commercially (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PCR was performed for different genes (ZO-1, ZO-2, occludin, beta-actin) in a final reaction volume of 20 µl containing 2 µl of the cDNA, 10 µl master mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 20 pmol forward primer, 20 pmol reverse primer, and 5 µl water. PCR amplification reactions were performed with the following program: 95 °C-10.00 min [95 °C-50 s, 55 °C-1.00 min, 72 °C-1.00 min] × 35 cycles, 72 °C-5.00 min, 4 °C-∞. The amplified products were resolved on an agarose gel (prepared in 1× TAE) in the presence of ethidium bromide and the images were recorded with a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad). The band intensities of the PCR product were normalized to beta-actin band. The list of primer sequences is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to detect the expression of MMP-9, occludin, and claudin-5 in cerebral vessels of different rat groups. Animals were killed with an anesthetic overdose, infused immediately with PBS through the left ventricle for exsanguination. The brains were carefully harvested, washed with 50 mM PBS (pH 7.4), and used to prepare frozen blocks with OCT media (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC, USA). After that, frozen brain blocks were used to cut 20-µm brain sections using a cryostat (Leica CM, USA). The tissue sections were blocked with 5 % BSA for 40 min at RT and incubated with a primary antibody [MMP-9 (Abcam, USA), claudin-5 and occludin (Santa cruz, USA)] overnight at 4 °C. The unbound antibody was washed with PBS and the sections were incubated with corresponding fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibodies for 60 min at room temperature. The slides were further stained with DAPI (1:10,000) for 15 min and mounted with anti-fade mounting media. The images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (×60 objectives, FluoView 1000, Olympus, PA, USA). Total fluorescence intensity was measured with image analysis software (Image-Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test. Differences were considered to be significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Effect of MMP inhibitor GM6001 on hypertension

Dahl salt-sensitive (Dahl/SS) rats showed higher baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP; expressed in mm Hg) (145 ± 7) than Lewis controls (88 ± 5) on normal diet (Fig. 1a). After 2 weeks of high-salt diet feeding, MAP was increased significantly and maintained till the end of the experiment in Dahl/SS rats (194 ± 8). However, no change in MAP was observed in Lewis rats (91 ± 8) fed on high-salt diet throughout the experiment (Fig. 1). Interestingly, Dahl/SS rats showed considerable decrease in MAP (172 ± 9) after 2 weeks of GM6001 administration whereas no effect of GM6001 treatment was observed in MAP of Lewis rats (88 ± 8) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial blood pressure (BP) measurement from Lewis and Dahl/SS rats fed on 4 % salt diet. After 6 weeks of salt diet, MMP inhibitor GM6001 treatment was started in Lewis and Dahl/SS rats and continued till the end of the experiment. BP was measured through tail-cuff method. Data represents mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05-vs. Dahl/SS + vehicle. (n = 6/group)

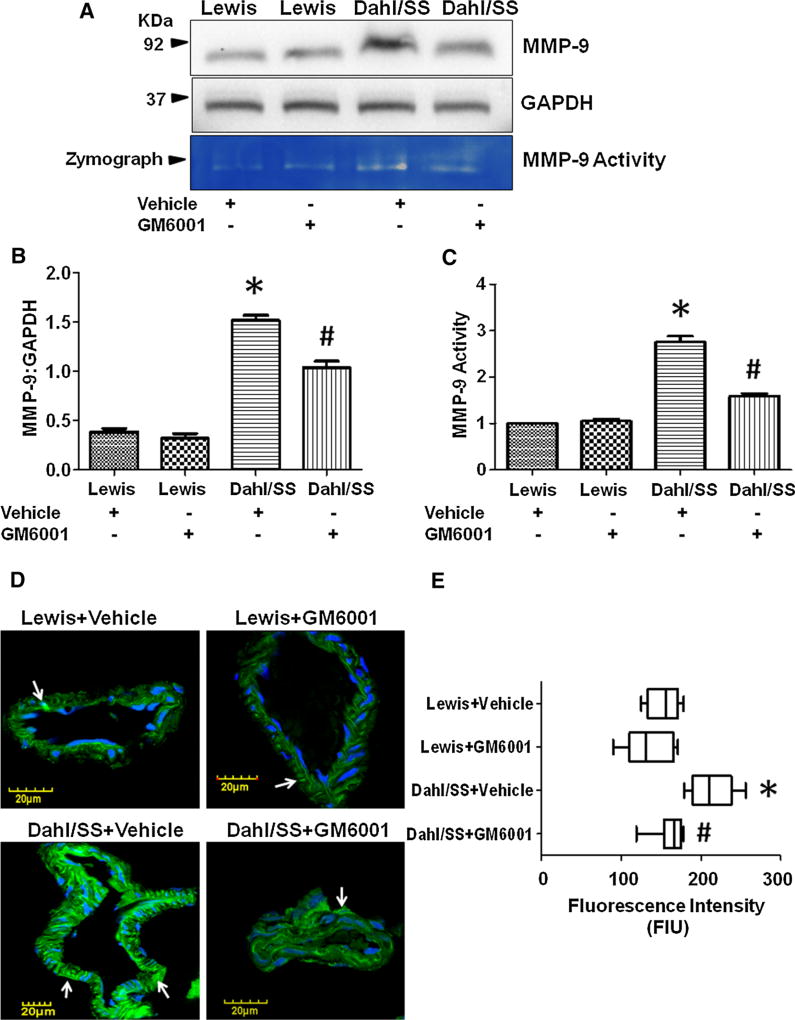

GM6001 administration decreased MMP-9 expression and activity

In order to determine whether MMP-9 level is increased in salt-sensitive Dahl rats and whether pharmacological galardin GM6001 administration ameliorates MMP-9 level, we determined MMP-9 expression and activity. Western blot analysis for MMP-9 levels (expressed in arbitrary units; AU) showed high levels in Dahl/SS rats (1.514 ± 0.05) treated with vehicle as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (0.384 ± 0.036) (Fig. 2a, b). Likewise, high gelatin degradation activity of MMP-9 (expressed in AU) was detected in vehicle-treated Dahl/SS rats (2.750 ± 0.13) compared to Lewis rats (Fig. 2a, c). The treatment of GM6001 significantly decreased MMP-9 expression and activity in Dahl/SS rats (1.036 ± 0.064 and 1.586 ± 0.061, respectively) whereas, no change in MMP-9 expression/activity was observed in treated Lewis rats (0.318 ± 0.05 and 1.048 ± 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 2a–c).

Fig. 2.

a Western blot image showing MMP-9 expression and gelatin zymography image showing MMP-9 activity in Dahl/SS and Lewis rats treated with vehicle and GM6001. b Bar graph showing densitometry analysis for MMP-9 expression, c densitometry analysis for MMP-9 activity, d immunohistochemistry images showing MMP-9 expression (green color indicated with white arrows) in brain vessels. Nuclei were stained with DapI (blue color), and e Box plot showing vascular MMP-9 fluorescence intensity in Dahl/SS and Lewis rats treated with vehicle and GM6001. Data represents mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05-vs. Lewis + vehicle and Lewis + GM6001, #p < 0.05-vs. Dahl/SS + vehicle. (Color figure online)

We further determined MMP-9 expression (expressed in fluorescence intensity unit; FIU) in cerebral vessels using IHC analysis. Dahl/SS rats treated with vehicle showed higher vascular MMP-9 expression (212.3 ± 8.87) as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (Fig. 2d, e). However, GM6001 treatment normalized the MMP-9 expression in salt-sensitive Dahl rats (162.0 ± 6.16) close to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (153.3 ± 6.377), whereas no significant effect was observed in GM6001-treated Lewis rats (134.4 ± 9.80) as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (Fig. 2d, e).

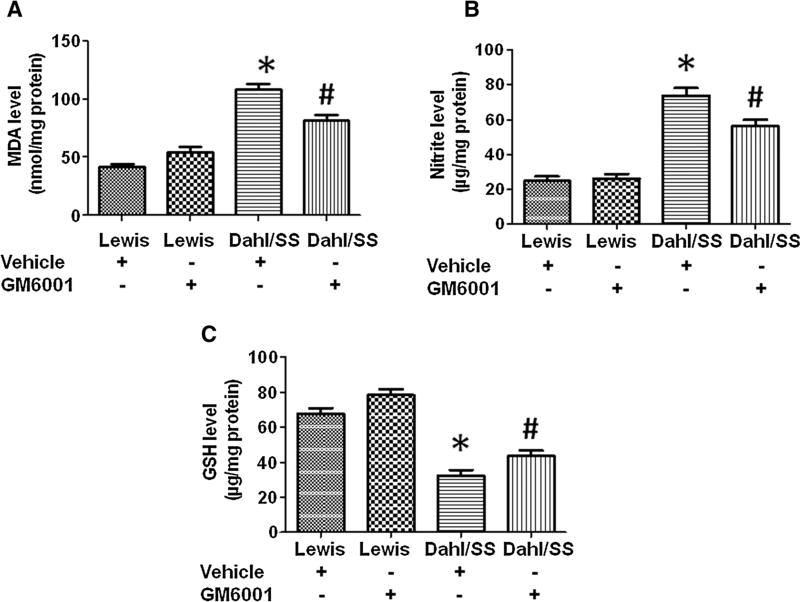

MMP-9 inhibition ameliorated oxidative stress

To evaluate the effects of MMP-9 inhibition on oxidative stress, we assessed brain MDA (expressed in nmol/mg of protein), nitrite (expressed in µg/mg of protein), and GSH (expressed in µg/mg of protein) levels. Vehicle-treated Dahl/SS rats showed significantly high levels of MDA (108.2 ± 5.12) and nitrite (73.80 ± 4.34) levels as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (MDA, 42.20 ± 2.31; Nitrite, 24.80 ± 2.69) (Fig. 3a, b). Significant decrease in MDA (81.80 ± 4.97) and nitrile levels (56.40 ± 3.57) were observed in Dahl/SS rats treated with GM6001. Lewis rats treated with GM6001 did not show any considerable change in MDA (54.40 ± 4.76) and nitrile levels (26.00 ± 2.82) as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (Fig. 3a, b). Since decrease in anti-oxidant levels also indicates oxidative stress, we assessed thiol content in rat brain tissues. There was remarkable decrease in total GSH content in Dahl/SS rats treated with vehicle (32.20 ± 3.40) as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (67.60 ± 3.356) (Fig. 3c). GM6001 administration restored total GSH contents in Dahl/SS rats (43.60 ± 3.22), whereas no significant change in the thiol content was observed in Lewis rats (78.40 ± 3.43) (Fig. 3c). These findings clearly indicate that inhibition of MMP-9 level alleviates oxidative stress.

Fig. 3.

Effect of GM6001 on malondialdehyde (MDH) (a), nitrite (b), and intracellular reduced glutathione (GSH) (c) levels in Lewis + vehicle, Lewis + GM6001, Dahl/SS + vehicle and Dahl/SS + GM6001 rats. Data represents mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05-vs. Lewis + vehicle and Lewis + GM6001, #p < 0.05-vs. Dahl/SS + vehicle

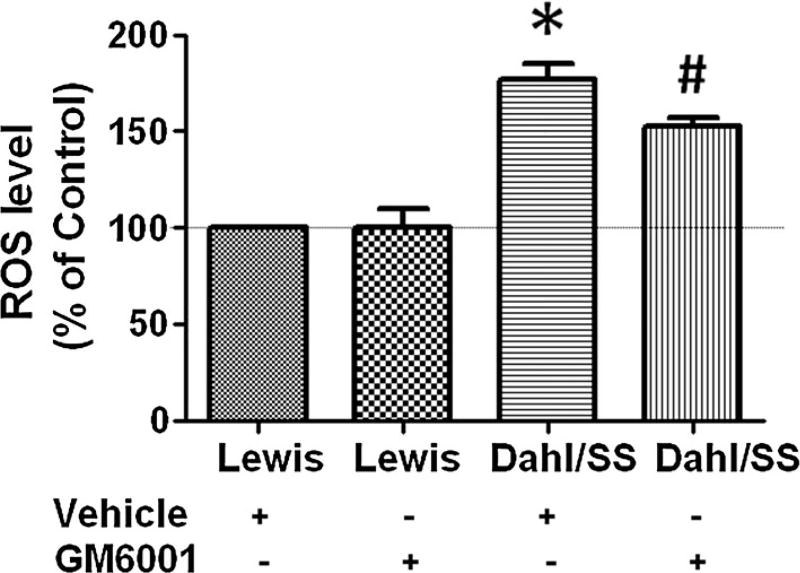

MMP-9 inhibition mitigated vascular ROS level

The ROS content (expressed as percentage of control) was measured in cellular fraction isolated from different experimental rat groups. Vehicle-treated Dahl/SS rats showed highest ROS production (177 ± 8) as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats (Fig. 4). Interestingly, GM6001 treatment significantly mitigated ROS production in salt-sensitive Dahl rats (152.8 ± 4.14), and no effect in ROS production was observed in GM6001-treated Lewis rats (100.8 ± 9.11) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) determination using 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) diacetate in Dahl/SS and Lewis rats treated with vehicle and GM6001. Data represents mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05-vs. Lewis + vehicle and Lewis + GM6001, #p < 0.05-vs. Dahl/SS + vehicle

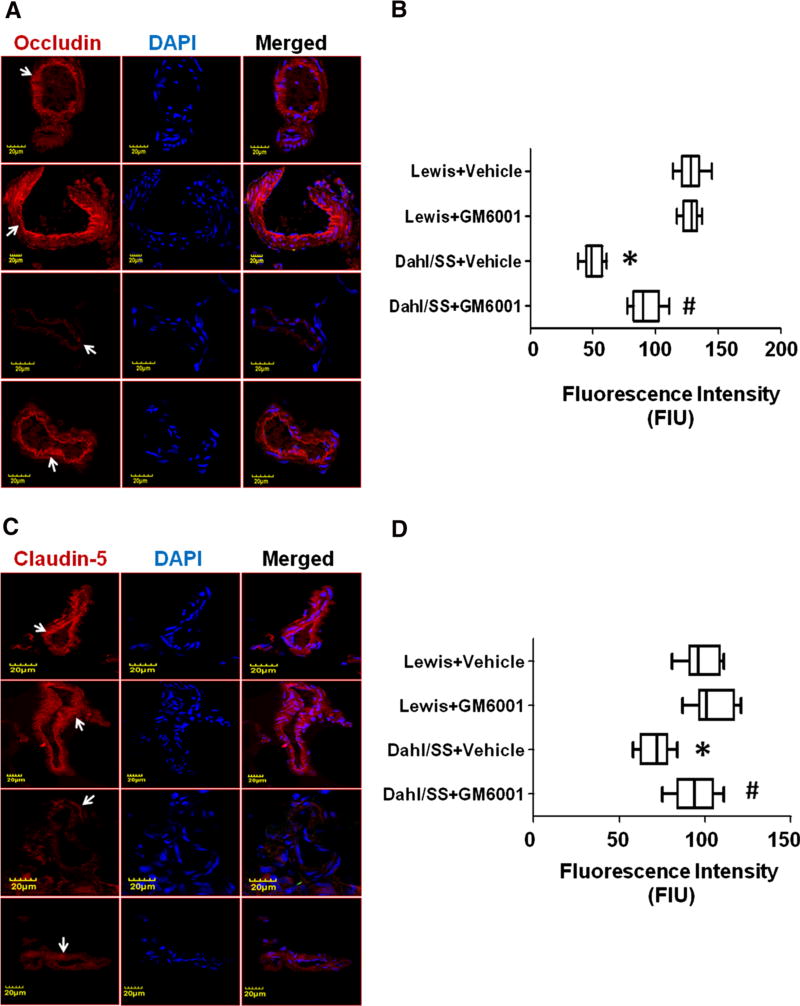

MMP-9 attenuation mitigated endothelial tight junctions

To understand the effect of pharmacological MMP inhibitor on endothelial junction barrier, transcript levels of endothelial TJs (ZO-1, ZO-2, and Occludin) were determined. The values of transcript expressions were analyzed as fold expression. Quantitative mRNA assessment using RT-PCR showed lowest expression of ZO-1 (0. 129 ± 0.020), ZO-2 (0.385 ± 0.032), and occludin (0.554 ± 0.041) in Dahl/SS rats treated with vehicle as compared to Lewis rats treated with vehicle (Fig. 5a, b). Administration ofGM6001 restored ZO-1 (0.782 ± 0.047), ZO-2 (0.637 ± 0.029), and occludin levels (0.710 ± 0.041) in Dahl/SS rats, while no effect was observed in GM6001-treated Lewis rats (ZO-1, 1.09 ± 0.067; ZO-2, 1.100 ± 0.077) (Fig. 5a, b). These results suggest that MMP-9 inhibition normalized endothelial TJs.

Fig. 5.

a Agarose gel images showing amplified PCR products of ZO-1, ZO-2, and occludin genes and, b RT-PCR analysis for ZO-1, ZO-2, and occludin genes in Dahl/SS and Lewis rats treated with vehicle and GM6001. Data represents mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05-vs. Lewis + vehicle and Lewis + GM6001, #p < 0.05-vs. Dahl/SS + vehicle

We further determined the expression of endothelial TJs, occludin and claudin-5 (expressed in FIU), in brain cortical vessels. IHC analysis showed reduced occludin and claudin-5 intensity in salt-sensitive rats treated with vehicle (occludin, 50.56 ± 2.57; claudin-5, 71.22 ± 3.03); however, no change in the fluorescent intensity of occludin and claudin-5 were observed in Lewis rats treated with vehicle (occludin, 128.1 ± 3.01; claudin-5, 98.72 ± 3.48) (Fig. 6a–d). Treatment of GM6001 restored occludin and claudin-5 expression levels in Dahl/SS rats (occludin, 91.75 ± 3.80; claudin-5, 94.44 ± 4.02) (Fig. 6a–d). There were no considerable changes revealed in the fluorescence intensity of occludin and claudin-5 in GM6001-treated Lewis rats (occludin, 127.9 ± 2.22; claudin-5, 104.6 ± 3.87) (Fig. 6a–d).

Fig. 6.

a Immunohistochemistry (IHC) images showing endothelial tight junction occludin expression in cerebral blood vessels. Left panel shows occludin (red color indicated with white arrows) expression, middle panel shows DapI stained nuclei and right panel shows merged images. b Box plot showing IHC analysis for occludin. c IHC images showing endothelial tight junction claudin-5 expression in cerebral blood vessels. Left panel shows claudin-5 (red color indicated with white arrows) expression, middle panel shows DapI stained nuclei and right panel shows merged images. d Box plot showing IHC analysis for claudin-5. Data represents mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05-vs. Lewis + vehicle and Lewis + GM6001, #p < 0.05-vs. Dahl/SS + vehicle. (Color figure online)

Discussion

The role of hypertension as a causative factor of eutrophic remodeling is well studied in cerebral vessels. In the present report, we studied pharmacological intervention using synthetic galardin (GM6001) that can potentially attenuate hypertension and hypertensive cerebral vasculopathy by normalizing MMP-9, which is upregulated in cerebrovascular complications. To study galardin effect on hypertension, we used Dahl salt-sensitive rat model, a well-established model of hypertension [23]. High-salt diet to Dahl-SS rats increased MAP, which is in agreement with the previous findings on the rodent strain to obtain hypertensive phenotypic trait [24, 25]. After 6 weeks of high-salt diet, GM6001 treatment was given to Dahl-SS rats and Lewis control rats. GM6001 is a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor and has been previously tested for various cerebral pathologies; for example, intracerebral hemorrhage [26], altered cellular migration [27], and BBB permeability [28]. MMPs are one of the main culprits involved in cerebral disease progression and we and others have reported that MMP-9, a gelatinase, is associated with impairment of the neurovasculature function, hemorrhagic transformations, neurodegeneration, and BBB disruption [15, 17, 29, 30]. In this current report, we established that attenuating MMP-9 using a synthetic inhibitor, GM6001 rescued hypertension-induced vasculopathy. GM6001 treatment did not alter total body weight (expressed in gram) of Dahl-SS rats as compared to untreated rats (431.33 ± 6.9 vs. 430 ± 3.0). Similarly, no change in total body weight was observed in GM6001 treated and untreated Lewis control rats (395.3 ± 12.7 vs. 392 ± 3.4). Alongside, total brain weight (expressed in gram) was also found unchanged in treated Dahl-SS rats as compared to untreated ones (1.73 ± 0.08 vs. 1.77 ± 0.2). The brain weights of Lewis control with and without GM6001 treatment were also remain unaffected (1.82 ± 0.12 vs. 1.88 ± 0.05). Interestingly GM6001 significantly reduced MAP in Dahl-SS rats starting from 2nd week of treatment and maintained throughout the treatment. Though the pathobiology of hypertension affecting cerebral vasculature is not completely understood, there is clear evidence that the condition can itself alter cerebrovascular integrity [31]. Ample literature indicates that mitigating hypertension can possibly rescue whole body pathological events associated with chronic hypertension. Hence, normalizing hypertension with GM6001 in Dahl-SS rats can reduce hypertension-induced cerebrovascular pathological sequelae.

GM6001 belongs to Ilomastat (hydroxamate family) and binds to the zinc atom present in active-site of MMPs and its application in human clinical trials did not report significant toxicity. The synthetic inhibitor has a broad spectrum of activity against several MMPs. We confirmed anti-metalloproteinase activity of GM6001 by quantitating at MMP-9 expression in different experimental rat group brains. Gelatin zymography analysis showed reduced degradation in GM6001-treated Dahl-SS rat brains as compared to vehicle-treated Dahl-SS rats. Furthermore, as compared to untreated Dahl-SS rats brains, GM6001-treated Dahl-SS rats showed significantly reduced MMP-9 in cerebral vasculature as evident from immunohistochemistry analysis. However, there was no change in MMP-9 level in Lewis rats treated without or with GM6001. Normalization of MMP-9 with GM6001 in Dahl-SS rats suggested alleviation of cerebral pathology. A large body of evidence suggest that MMPs are induced under oxidative stress [32, 33], and reduction in MMPs can prevent oxidative stress [34]. The ongoing research clearly indicates that the regulated activity of MMP-9 is critical for cerebral development and functions [35]. The induction of MMP-9 has been reported in many basic and clinical studies where MMP-9 was found to be associated in cerebral pathologies [15, 36–38]. Although several studies suggest that oxidative-nitrosative stress induces MMP-9 [15, 32, 33], some studies also indicate that MMPs are upstream of ROS generation [39], and a decrease in MMPs can decrease oxidative stress [34]. In a recent study, using double transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, GM6001 treatment decreased the MMP activity and oxidative stress [40]. Further, in SCp2 mouse mammary epithelial cells, MMP-3-induced ROS and subsequent DNA damage was rescued by treatment with GM6001 [41]. Although the above studies did not investigate the mechanism of MMP-induced oxidative stress, they support the role of MMP in ROS production. It is possible that other proteases such as MMP-9 could substitute for oxygen radical formation similarly in other disease scenarios. Altogether these reports suggest that the induction of ROS and MMP is bidirectional and hence, attenuation of ROS or MMPs can mitigate pathological outcomes. Brain vessels are prone to sustain damage through ROS production which together with RNS (reactive nitrogen species) cause oxidative-nitrosative stress during hypertension [31]. In the current study, we found enhanced ROS production in vehicle-treated Dahl-SS rat brain as compared to vehicle-treated Lewis rats. We also found high brain MDA and Nitrite levels (indicative of enhanced free radical generation) and reduced GSH level (indicative of low anti-oxidant levels) in vehicle-treated Dahl-SS rats as compared to control. Induced ROS, MDA, total nitrite, and reduced GSH levels in hypertensive rats are parameters which represent high oxidative-nitrosative stress in the hypertensive rat cerebral vasculature. Earlier studies on AngII-induced hypertension suggested increase ROS production in pial arterioles [42, 43]; however, in the current report, we confirmed high oxidative stress in cerebral vasculature in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Similar to oxidative stress, we have earlier observed that MMP-9 inhibition using small molecule inhibitors protects BBB permeability [15].

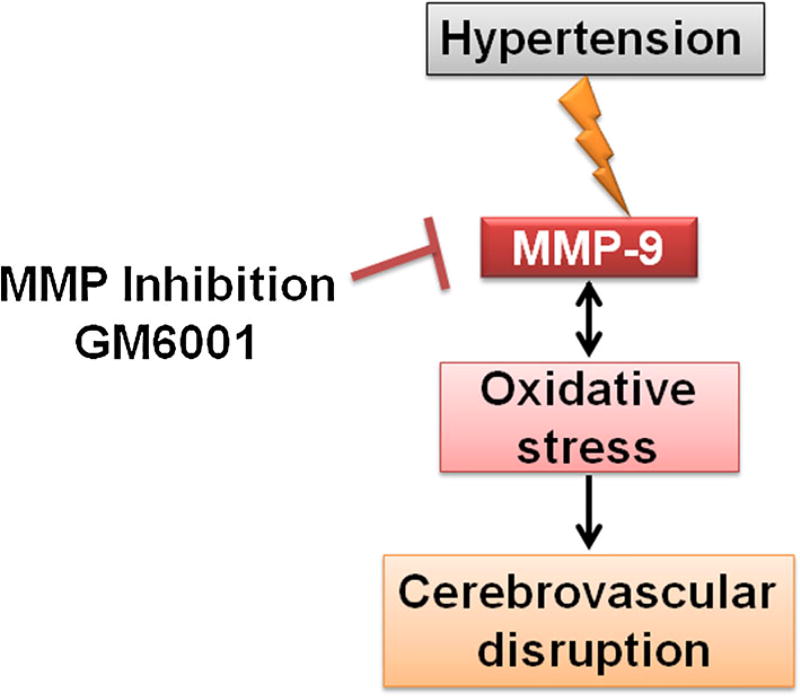

Oxidative stress along with induced MMP-9, affects selective barrier function of the BBB which is regulated through specialized regulatory junctional connections maintained around endothelial cells in cerebral vasculature. The studies report that impairment of cerebrovascular junctions can raise BBB permeability and can be potentially involved in the pathogenesis of many neurological disorders, such as; stroke, trauma, brain tumor, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer disease, including hypertension [44]. The specialized barrier property of cerebral vasculature is highly regulated by TJs (occludin, claudin-5) and associated proteins zona occluden (ZO-1 and ZO-2). A previous study suggested that the barrier functions can be altered with perturbation in the extracellular loops of occludin [45]. Similarly, another study reported that mice deficient in claudin-5 showed enhanced BBB permeability for molecules more than 800 kDa [46]. Besides, the pathogenic role of induced MMP-9 in altering occludin and claudin-5 in focal cerebral ischemia [47], the effect of occludin, claudin-5, ZO-1, and ZO-2 was also studied in diabetic retinopathy [48]. These studies suggest the role of induced MMP-9 in BBB dysfunction either by altering or chopping off TJs. Creating hypertensive trait in Dahl-SS rats, we found reduced TJs (occludin and claudin-5) and zona occludens (ZO-1 and ZO-2) which is suggestive of compromised barrier function of cerebral vasculature. Interestingly, MMP-9 inhibition by GM6001 rescued TJs levels. These results clearly indicate the involvement of MMP-9 in cerebrovascular pathologies and the importance of restoring functional BBB by normalizing MMP-9 during hypertension. A working hypothesis is presented as Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Hypothesis Hypertension induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 and oxidative stress which cumulatively disrupt cerebrovascular junctions

In conclusion, our data clearly suggests a mechanistic involvement of MMP-9 in aggravating hypertension-induced cerebrovascular pathologies. Although clinical trials targeting MMPs have not been successful, the probability of functional MMP-9 involvement and its inhibition in mitigating pathophysiological state cannot be ruled out. In this regard, our results interestingly suggest functional restoration of brain vasculature by normalizing MMP-9 levels by pharmacological interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL107640-NT.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11010-015-2623-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Gorelick PB. New horizons for stroke prevention: PROGRESS and HOPE. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freis ED. The role of salt in hypertension. Blood Press. 1992;1:196–200. doi: 10.3109/08037059209077662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swales JD. Salt and blood pressure. Blood Press. 1992;1:201–204. doi: 10.3109/08037059209077663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meneely GR, Ball CO. Experimental epidemiology of chronic sodium chloride toxicity and the protective effect of potassium chloride. Am J Med. 1958;25:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(58)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawasaki T, Delea CS, Bartter FC, Smith H. The effect of high-sodium and low-sodium intakes on blood pressure and other related variables in human subjects with idiopathic hypertension. Am J Med. 1978;64:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberger MH. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 1996;27:481–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecchelli R, Berezowski V, Lundquist S, Culot M, Renftel M, Dehouck MP, Fenart L. Modelling of the blood-brain barrier in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:650–661. doi: 10.1038/nrd2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:173–185. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mark KS, Davis TP. Cerebral microvascular changes in permeability and tight junctions induced by hypoxia-reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1485–H1494. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00645.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumbach GL, Heistad DD. Cerebral circulation in chronic arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 1988;12:89–95. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.12.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cauwe B, Van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G. The biochemical, biological, and pathological kaleidoscope of cell surface substrates processed by matrix metalloproteinases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:113–185. doi: 10.1080/10409230701340019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flamant M, Placier S, Dubroca C, Esposito B, Lopes I, Chatziantoniou C, Tedgui A, Dussaule JC, Lehoux S. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in early hypertensive vascular remodeling. Hypertension. 2007;50:212–218. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalani A, Kamat PK, Chaturvedi P, Tyagi SC, Tyagi N. Curcumin-primed exosomes mitigate endothelial cell dysfunction during hyperhomocysteinemia. Life Sci. 2014;107:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalani A, Kamat PK, Familtseva A, Chaturvedi P, Muradashvili N, Narayanan N, Tyagi SC, Tyagi N. Role of micro-RNA29b in blood-brain barrier dysfunction during hyperhomocysteinemia: an epigenetic mechanism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1212–1222. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosell A, Ortega-Aznar A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Ribo M, Molina CA, Lo EH, Montaner J. Increased brain expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 after ischemic and hemorrhagic human stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:1399–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000223001.06264.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalani A, Kamat PK, Givvimani S, Brown K, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC, Tyagi N. Nutri-epigenetics ameliorates blood-brain barrier damage and neurodegeneration in hyperhomocysteinemia: role of folic acid. J Mol Neurosci. 2014;52:202–215. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0122-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lominadze D, Roberts AM, Tyagi N, Moshal KS, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine causes cerebrovascular leakage in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1206–H1213. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00376.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen F, Ohashi N, Li W, Eckman C, Nguyen JH. Disruptions of occludin and claudin-5 in brain endothelial cells in vitro and in brains of mice with acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2009;50:1914–1923. doi: 10.1002/hep.23203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muradashvili N, Tyagi R, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC, Lominadze D. Ablation of MMP9 gene ameliorates paracellular permeability and fibrinogen-amyloid beta complex formation during hyperhomocysteinemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1472–1482. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pushpakumar SB, Kundu S, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC, Sen U. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition mitigates renovascular remodeling in salt-sensitive hypertension. Physiol Rep. 2013;1:e00063. doi: 10.1002/phy2.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamat PK, Tota S, Saxena G, Shukla R, Nath C. Okadaic acid (ICV) induced memory impairment in rats: a suitable experimental model to test anti-dementia activity. Brain Res. 2010;1309:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwai J, Heine M. Dahl salt-sensitive rats and human essential hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1986;4:S29–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapp JP. Dahl salt-susceptible and salt-resistant rats. A review. Hypertension. 1982;4:753–763. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bright R, Steinberg GK, Mochly-Rosen D. DeltaPKC mediates microcerebrovascular dysfunction in acute ischemia and in chronic hypertensive stress in vivo. Brain Res. 2007;1144:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zozulya AL, Reinke E, Baiu DC, Karman J, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Dendritic cell transmigration through brain microvessel endothelium is regulated by MIP-1alpha chemokine and matrix metalloproteinases. J Immunol. 2007;178:520–529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Tsirka SE. Neuroprotection by inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases in a mouse model of intracerebral haemorrhage. Brain. 2005;128:1622–1633. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tasaki A, Shimizu F, Sano Y, Fujisawa M, Takahashi T, Haruki H, Abe M, Koga M, Kanda T. Autocrine MMP-2/9 secretion increases the BBB permeability in neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:419–430. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fingleton B. Matrix metalloproteinases as valid clinical targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:333–346. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui J, Chen S, Zhang C, Meng F, Wu W, Hu R, Hadass O, Lehmidi T, Blair GJ, Lee M, Chang M, Mobashery S, Sun GY, Gu Z. Inhibition of MMP-9 by a selective gelatinase inhibitor protects neurovasculature from embolic focal cerebral ischemia. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2008;7:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tyagi N, Gillespie W, Vacek JC, Sen U, Tyagi SC, Lominadze D. Activation of GABA-A receptor ameliorates homocysteine-induced MMP-9 activation by ERK pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:257–266. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyagi N, Qipshidze N, Munjal C, Vacek JC, Metreveli N, Givvimani S, Tyagi SC. Tetrahydrocurcumin ameliorates homocysteinylated cytochrome-c mediated autophagy in hyperhomocysteinemia mice after cerebral ischemia. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;47:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasche Y, Copin JC, Sugawara T, Fujimura M, Chan PH. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition prevents oxidative stress-associated blood-brain barrier disruption after transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1393–1400. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinhard SM, Razak K, Ethell IM. A delicate balance: role of MMP-9 in brain development and pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:280. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SC, Singh M, Huang J, Prestigiacomo CJ, Winfree CJ, Solomon RA, Connolly ES., Jr Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:642–666. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199709000-00027. (discussion 646–7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jickling GC, Liu D, Stamova B, Ander BP, Zhan X, Lu A, Sharp FR. Hemorrhagic transformation after ischemic stroke in animals and humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:185–199. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalani A, Kamat PK, Tyagi N. Diabetic stroke severity: epigenetic remodeling and Neuro-glio-vascular dysfunction. Diabetes. 2015 doi: 10.2337/db15-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Touyz RM. Mitochondrial redox control of matrix metalloproteinase signaling in resistance arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:685–688. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216428.90962.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Alloza M, Prada C, Lattarulo C, Fine S, Borrelli LA, Betensky R, Greenberg SM, Frosch MP, Bacskai BJ. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces oxidative stress associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy in vivo in transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1636–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radisky DC, Levy DD, Littlepage LE, Liu H, Nelson CM, Fata JE, Leake D, Godden EL, Albertson DG, Nieto MA, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature. 2005;436:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature03688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girouard H, Park L, Anrather J, Zhou P, Iadecola C. Angiotensin II attenuates endothelium-dependent responses in the cerebral microcirculation through nox-2-derived radicals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:826–832. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000205849.22807.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Faraci FM. Critical role for CuZn-superoxide dismutase in preventing angiotensin II-induced endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 2005;46:1147–1153. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000187532.80697.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong V, Gumbiner BM. A synthetic peptide corresponding to the extracellular domain of occludin perturbs the tight junction permeability barrier. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:399–409. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nitta T, Hata M, Gotoh S, Seo Y, Sasaki H, Hashimoto N, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:653–660. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y, Estrada EY, Thompson JF, Liu W, Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinase-mediated disruption of tight junction proteins in cerebral vessels is reversed by synthetic matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in focal ischemia in rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:697–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkins BT, Lundeen TF, Norwood KM, Brooks HL, Egleton RD. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability and altered tight junctions in experimental diabetes in the rat: contribution of hyperglycaemia and matrix metalloproteinases. Diabetologia. 2007;50:202–211. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.