Abstract

Objective

Application of Kilohertz Frequency Alternating Current (KHFAC) waveforms can result in nerve conduction block that is induced in less than a second. Conduction recovers within seconds when KHFAC is applied for about 5 – 10 minutes. This study investigated the effect of repeated and prolonged application of KHFAC on rat Sciatic nerve with bipolar platinum electrodes.

Approach

Varying durations of KHFAC at signal amplitudes for conduction block with intervals of no stimulus were studied. Nerve conduction was monitored by recording peak Gastrocnemius muscle force utilizing stimulation electrodes proximal (PS) and distal (DS) to a blocking electrode. The PS signal traveled through the block zone on the nerve, while the DS went directly to the motor end-plate junction. The PS/DS force ratio provided a measure of conduction patency of the nerve in the block zone.

Main Results

Conduction recovery times were found to be significantly affected by the cumulative duration of KHFAC application. Peak stimulated muscle force returned to pre-block levels immediately after cessation of KHFAC delivery when it was applied for less than about 15 minutes. They fell significantly but recovered to near pre-block levels for cumulative stimulus between 50 +/− 20 minutes, for the tested On / Off times and frequencies. Conduction recovered in two phases, an initial fast one (60–80% recovery), followed by a slower phase. No permanent conduction block was seen at the end of the observation period during any experiment.

Significance

This Carry-over Block Effect (COBE) may be exploited to provide continuous conduction block in peripheral nerves without continuous application of KHFAC.

Keywords: Nerve conduction block, High frequency nerve block, KHFAC, block persistence, in-vivo model

INTRODUCTION

Kilohertz frequency alternating current (KHFAC) nerve conduction block has been demonstrated to possess a number of desirable clinical characteristics (Kilgore and Bhadra 2014). KHFAC block may be established within seconds and can be rapidly reversed, with conduction returning to the nerve fibers within a few seconds (Kilgore and Bhadra 2004). Block is localized to a restricted area of the nerve near the electrode where the KHFAC signal is applied. KHFAC offers the prospect of arresting undesirable motor, sensory, and autonomic nerve activity, with focal and temporal precision, without having generalized side effects.

It has been shown in several animal species that nerves can recover conduction within seconds after the cessation of KHFAC, when it is delivered for a duration less than 5 to 10 minutes (Boger, Bhadra et al. 2008, Ackermann, Ethier et al. 2011). When acute nerve block studies were extended to continuous KHFAC delivery for more than 30 minutes, a residual reduction in conduction was observed after cessation of the KHFAC. Specifically, the nerve continued to show effects of conduction block which slowly recovered to normal conduction over minutes or sometimes hours . Carry-over block effect (COBE) with shorter durations of KHFAC application have also been reported. COBE has been observed in rat Vagus nerve (Waataja et al. 2011) with application of a 5 kHz waveform at amplitudes up to 8 mA, where the compound action potential (CAP) was recorded to verify lack of nerve conduction after one minute of 5 kHz application. Immediately after delivery of the 5 kHz, nerve conduction was partially blocked for periods up to five or more minutes, depending on the amplitude of the 5 kHz waveform. Persistence of conduction block following 5 or 10 kHz stimulation has also been reported in a frog sciatic nerve preparation (Yang et al, 2016).

Three distinct types of nerve recovery have been observed after KHFAC (Kilgore and Bhadra, 2014). A) Immediate Recovery: when KHFAC block was delivered to a previously unblocked nerve for periods less than approximately 15 minutes. This was characterized by full peak force recovery within 3 seconds after cessation of KHFAC. B) Fast Recovery: This type of recovery appeared after KHFAC has been delivered for periods over 15 minutes. This was characterized by a rapid recovery of evoked peak force within about three minutes. C) Slow Recovery: Slow recovery followed an initial phase of rapid recovery and appeared after KHFAC block was delivered for more than about 40 minutes. Full peak force recovery could take as long as two hours.

A measure of motor nerve conduction block can be characterized by applying two stimulating electrodes, one placed proximal (PS) to the blocking electrode and one placed distal (DS) to the blocking electrode (Bhadra and Kilgore 2005). The distal electrode is placed between the blocking electrode and the neuromuscular junction. In most cases, supramaximal narrow pulse stimulus, delivered independently through each electrode (PS and DS), results in the same peak twitch force generated by the innervated muscle. However, action potentials generated by the PS electrode travel through the region of nerve affected by the KHFAC blocking electrode prior to reaching the neuromuscular junction. Action potentials generated at the DS electrode do not pass the KHFAC region and only pass through a short region of untreated nerve before reaching the same neuromuscular junction. Therefore, twitch forces generated by the DS electrode provide an excellent standard related to the condition of the nerve under the KHFAC electrode. The ratio of the peak twitch force generated by the proximal electrode to the peak twitch force generated by the distal electrode should be 1.0. This ratio, referred to as the PS/DS ratio (Proximal Stimulation/Distal Stimulation) can be used as a measure of the patency of conduction in the nerve. Changes in the transmission capability of the nerve fibers caused by the KHFAC block are immediately apparent. The PS/DS ratio is insensitive to naturally occurring fatigue or other muscle-based changes, and is therefore ideal as an outcome measure for acute KHFAC nerve block studies.

In this present study, “carry-over block effect” (COBE) was systematically investigated. With KHFAC applied repeatedly for durations of 1 to 30 minutes, with intervals of 1 to 30 minutes, COBE has been reversible and did not appear to induce permanent change in nerve conduction.

METHODS and MATERIALS

All experimental animal protocols were approved by the local institutional animal care and use committee. Experiments were carried out on adult Sprague-Dawley rats. The general experimental preparation has been described previously in detail (Bhadra and Kilgore 2005). Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal). One hind limb was shaved, and an incision was made along the postero-lateral aspect of the thigh and leg. The sciatic nerve was exposed from 1 cm lateral to the spinal exit to its terminal branching into tibial and common peroneal nerves. The sural and common peroneal nerves were cut. The animal was stabilized on a customized fixture with a clamp on the ipsilateral tibia. The gastrocnemius–soleus muscle was exposed. The calcaneal tendon was transected and connected by a tendon clamp to an in-line force transducer (Entran, Fairfield, NJ) to measure isometric muscle force (resolution 0.005 N).

Study Sets

An exploratory set of experiments (Set A) was carried out on four animals. KHFAC at 20 kHz was applied for successive durations of 1, 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes in two animals, an additional 30 minutes in one of the animals, and 1, 30, 30 and 60 minutes in another animal. Durations between successive stimulus trains without stimulation were not set to any fixed time interval.

A study set (Set B) based on the experience from the trial set, was carried out on 21 animals. KHFAC was applied at 10 kHz for different On/Off durations in 16 animals. A 10/10 min On/Off repetition was carried out at 15 kHz in one animal, 20 kHz in 2 animals and 40 kHz in one animal. One other experiment was run at 40 kHz with 10/20 min On/Off timing. The total duration of high frequency stimulation, the sum of the On periods (cumulative KHFAC) ranged from 45 to 150 minutes.

Electrical Stimulation and KHFAC Block: Three platinum bipolar J-cuff electrodes manufactured in house (Foldes, Ackermann et al. 2011) were positioned along the nerve, as illustrated in Figure 1a. The proximal electrode (PS) was used to deliver stimulus from an isolated square-pulse stimulator (Grass S88, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI, USA) to maximally excite the gastrocnemius muscle. The central electrode was used to test KHFAC block and deliver the trains of sinusoidal KHFAC from a voltage-controlled function generator (Model 395, Willtek Communications GmbH, Ismaning, Germany). The distal electrode positioned between the blocking electrode and the muscle, was used to deliver distal stimulation (DS) to the muscle from another channel of a square-pulse stimulator (Grass S88, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI, USA). A LabView® (National Instruments, Austin, TX) program controlled the function generator to produce trains of KHFAC at the desired sequences at the required amplitude and frequency.

Figure 1.

a. Schematic of the experimental set-up with proximal, distal and KHFAC electrodes. b. Left panel showing sample record of peak evoked muscle forces with proximal (PS) and distal (DS) stimulation. In each Off interval without KHFAC stimulus, PS/DS was determined by the ratio of each PS evoked peak force to the average DS evoked response in the same interval. c: Showing a schematic of reduction and recovery of PS/DS during an interval without KHFAC, after application of KHFAC (On, minutes). Phase I: fast recovery, Phase II: slow recovery.

Experimental Protocol

Each experiment began by determining the block threshold (BT), the minimum KHFAC amplitude required to maintain a complete conduction block, for the applied frequency. The method of determining BT has been previously validated (Bhadra and Kilgore, 2005) and shown to be a robust and repeatable characteristic of KHFAC block. To determine the BT, a proximal supramaximal test stimulus was delivered to the nerve, initiating muscle twitches at 1 Hz. The voltage-controlled sinusoidal KHFAC waveform was turned on at 10 Vpp. Once the nerve reached the blocked state and the muscle fully relaxed with the force returning to baseline (after the onset response), the KHFAC amplitude was reduced in 1 V decrements, with a duration of 2 to 3 seconds for each step, until muscle twitches were again observed. The lowest KHFAC amplitude that still produced complete block was identified as the BT for the respective KHFAC frequency. A KHFAC amplitude above BT was used for the timed duration of block application during each experimental trial.

Each experiment was carried out with a predetermined time duration of KHFAC application (On time) with an intervening interval without any KHFAC stimulus (Off time). Stimulus On times ranged from 1 to 30 minutes and Off times ranged from 1 to 60 minutes. Experiments began with a few seconds of PS and DS, from which the PS/DS ratio could be determined. Then, KHFAC was applied to the central blocking electrode for the selected duration of time. During the Off time, supramaximal PS at 1 Hz, was applied to record peak evoked muscle forces. Forces evoked by some DS pulses were also recorded at the end of the same intervals. The PS/DS ratio during the interval between KHFAC trains was a measure of any persisting conduction reduction and its subsequent recovery.

Data extraction and analysis

Gastrocnemius forces evoked by PS stimulation and by DS pulses were recorded in the beginning of the experiments and during each Off period (Figure 1 b). In each Off interval, PS/DS was computed by each PS evoked force divided by the average DS in that interval. The PS/DS during Off intervals after application of KHFAC for some duration, typically showed an initial rapid recovery which was fit linearly (Phase I) to record degree of recovery and rate. A second slower Phase II was nonlinear, for which average mean rates were calculated (Figure 1c).

A fixed-effects Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used on the data sets. The output variables were peak force and PS/DS ratio. Tukey-Kramer HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) was used to assess group differences. The input variables tested for effects on the output variables were, KHFAC frequency, stimulus amplitude (mA), cumulative KHFAC in minutes, stimulation on time (minutes), stimulation off time (minutes). Data from each experiment in Study Set B, was also tested individually by ANOVA to determine the Cumulative duration (in minutes) of KHFAC at which there was a significant (p<0.01) reduction in the Peak Force (N) and in PS/DS during the Off periods.

RESULTS

The PS/DS ratio over the duration of an experiment was a reliable measure of change in conduction of the affected nerve under the blocking electrode, monitored during the Off interval without KHFAC application. Application of KHFAC for many minutes resulted in a drop in the force evoked by PS stimulation, with a resulting drop in PS/DS ratio, which generally recovered during the Off interval. The conduction changes showed a strong correlation to the summated duration in time of applied KHFAC, (cumulative KHFAC in minutes). In the preliminary Set A, the intervals between KHFAC (Off periods) were not regulated. KHFAC was reapplied after a few seconds of PS followed by DS stimulation. This may not have provided adequate time for recovery from the previous KHFAC application. In Study Set B, evoked force and the PS/DS showed a drop after an On period, with varying degrees of recovery in the Off period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Showing PS/DS during two experiments with repeated trains of KHAC at 10 kHz. During the Off intervals, PS and DS were applied to record muscle twitch force responses. Bar marks near baseline denote KHFAC On periods.

Above: 5 minutes On with 5 minutes Off intervals. Reduction in PS/DS was significant (p<0.01) after 75 minutes of cumulative KHFAC.

Below: 10 minutes On with 10 minutes Off intervals. Reduction in PS/DS was significant (p<0.01) after 70 minutes of cumulative KHFAC.

Three categories of response to KHFAC were observed. Immediate recovery was characterized by full peak force recovery within 1–3 seconds, when KHFAC block was delivered for periods less than approximately 10 minutes. Fast recovery was characterized by full peak force recovery within approximately one to two minutes. The peak force could recover more than 50% of full range in this duration. This type of recovery appeared after KHFAC was delivered for periods over 10 minutes or was delivered repeatedly for shorter periods. Slow recovery took place over several minutes to hours.

During recovery, reduction in evoked muscle force and the PS/DS ratio after KHFAC application for the selected On time, monitored during the Off period, typically showed two phases, a short rapid one (Phase I), followed by a longer slow rise (Phase II). Phase I lasted for about 50 to 150 seconds, over all the observed Off times. Recovery continued at a much slower rate for varying degrees of time, depending on the degree of PS/DS reduction and the duration of the Off interval.

KHFAC Parameters

The mean block threshold (BT) at 20 kHz in the four exploratory experiments (Set A) was 5.1 volts (SD 2.4) with mean applied voltage of 6.2 volts. In the study set experiments (Set B), mean BT was 4.0 volts (SD 2.1) for the frequency range of 10 to 40 kHz, (n=16, 10kHz; n=1, 15 kHz; n=2, 20kHz and n=1, 40 kHz). The mean applied voltage was 5.5 volts (SD 2.7). The cumulative duration of KHFAC application in Set A was 61 minutes in 2 experiments and 91 minutes and 121 minutes in one each. The cumulative KHFAC application time in Set B was Mean 88.4 minutes (SD 33.8) with range of 30 to 150 minutes.

Carry-over Block Effect (COBE)

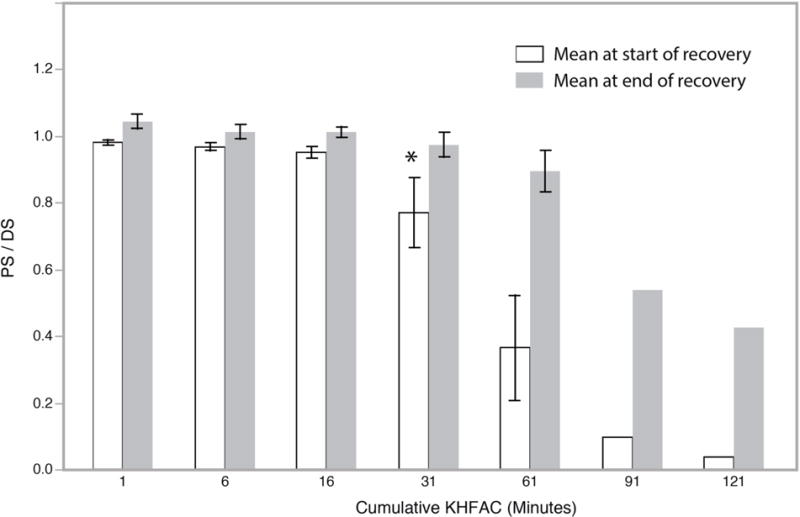

Experimental Set A: In the four initial experiments, conduction loss as indicated by a reduction in PS/DS ratio was significantly affected by cumulative KHFAC duration in minutes (Figure 3). KHFAC application for cumulative durations less than 30 minutes, resulted in nearly complete recovery during the non-stimulation interval. When KHFAC was delivered for more than 30 minutes (cumulative), peak force and PS/DS tended to be significantly reduced after the cessation of KHFAC. Recovery required tens of minutes, over the ensuing period. This reduction was a measure of the persistence of conduction block after cessation of KHFAC application. . One way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer HSD showed that loss in conduction was significantly increased with more than 30 minutes of cumulative KHFAC (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Study Set A. Mean (+/− 1 SD) of PS/DS at the start and end in an Off period without stimulus, after a duration of Cumulative KHFAC (in minutes) applied up to that time. Mean at start of recovery is at the end of a given period of cumulative KHFAC. The reduction in value below 1.0 is a measure of conduction loss. Mean at end of recovery is a measure of gain in conduction before the next KHFAC application. The * indicates the cumulative KHFAC after which there was a statistically significant reduction in the mean at start of recovery.

Experimental Set B: Sixteen animals were evaluated at 10 kHz, using duty cycles that ranged from 1 minute on/ 1 minute off, to 30 minutes on/ 60 minutes off. Five animals were tested with higher KHFAC frequencies. In each experiment, ANOVA of peak force and PS/DS in each Off interval was used to determine the cumulative KHFAC at which there was significant (p<0.01) reduction (Table I). In general, longer Off intervals required longer durations of cumulative KHFAC for significant reduction.

Table I.

Top:Study Set A, showing the sequence of applied KHFAC On times and cumulative KHFAC in the four experiments.

Below: Study Set B, shows the Mean cumulative KHFAC (in minutes) for significant reduction, p<0.01, in peak force and in PS/DS (n= Number of experiments at given On and Off duty cycle).

| Set A | ||

|---|---|---|

| ID No. | Sequence of On Times (minutes) | Cumulative KHFAC (minutes) |

| 1 | 1, 5, 10, 15, 30 | 61 |

| 2 | 1, 5, 10, 15, 30 | 61 |

| 3 | 1, 5, 10, 15, 30, 30 | 91 |

| 4 | 1, 30, 30, 60 | 121 |

| Set B | Mean cumulative KHFAC (minutes) for significant reduction in: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On Time (min) |

Off Time (min) |

n= | Peak Force | PS/DS |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 21 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 | 37.5 | 55 |

| 5 | 10 | 1 | 70 | 85 |

| 10 | 10 | 9 | 44 | 53 |

| 10 | 20 | 3 | 43 | 50 |

| 15 | 15 | 1 | 60 | 75 |

| 15 | 30 | 1 | 60 | 60 |

| 20 | 20 | 2 | 70 | 70 |

| 30 | 60 | 1 | 90 | 90 |

Mean reduction in conduction and ensuing recovery are shown for cumulative durations of KHFAC in Figure 4. Significant reduction (Tukey Kramer HSD at p<0.01) in peak force with cumulative duration of KHFAC was, mean 49.5 minutes (SD 19.8) and median 50 minutes. The cumulative KHFAC for significant reduction in the PS/DS ratio(Tukey Kramer HSD at p<0.01), mean was 57.6 minutes (SD 20.6), median 60 minutes. Significant decrease in PS/DS ratio was related directly to duration of On time and inversely to duration of Off time in general. Reduction in PS/DS showed significant effects due to cumulative KHFAC, applied frequency (kHz) and duration of the Off period at p<0.0001, and the duration of the On time at p<0.0002.

Figure 4.

Study Set B. Mean (+/− 1 SD) of PS/DS at the start and end in an Off period without stimulus, after a duration of Cumulative KHFAC (in minutes) applied up to that time. Mean at start of recovery is at the end of a given period of cumulative KHFAC. The reduction in value below 1.0 is a measure of conduction loss. Mean at end of recovery is a measure of gain in conduction before KHFAC application in the next On period. The * indicates the cumulative KHFAC after which there was a statistically significant reduction in the mean at start of recovery.

Recovery

In the preliminary Set A, conduction recovered to a PS/DS of higher than 0.5 after 60 or more minutes of KHFAC within the observation period (Figure 3). However, in the preliminary set, the recovery period was truncated before recovery had plateaued. Therefore, it is possible that further recovery could have occurred with a longer observation period. Total Recovery was significantly affected by cumulative KHFAC duration (in minutes, p=0.013). Total Recovery was significantly reduced after cumulative KHFAC delivery of more than 60 minutes (Tukey Kramer HSD, Alpha = 0.05).

Experimental Set B: Recovery of conduction after each Off duration is shown in Figure 4 as a function of cumulative KHFAC. PS/DS recovered to a mean value of 0.91 (SD 0.15), median 0.96. Even with long duration of cumulative KHFAC, where there was a progressive loss of conduction immediately after cessation of KHFAC, PS/DS values recovered nearly completely during the final Off period at the end of each experiment (typically 30–50 minutes). Total recovery was affected by the frequency of KHFAC (p<0.0005), the cumulative KHFAC (p<0.0001), and the Off interval (p<0.0073).

Recovery Rates

As mentioned before, recovery of evoked force and the PS/DS showed two phases, an initial rapid rise, followed by a slower second phase. The increase in phase I was fitted linearly and durations and rates were determined for each event in individual Off intervals. In Set A, where Off times without stimulation were brief (typically 1 to 2 minutes), the mean duration of Phase I was 40.6 seconds (SD 20.7, median 39 seconds, n=22 events). For the second phase, the median duration was 152 seconds, with mean of 32 minutes, which included the terminal recovery periods of observation. In the Experimental Set B, the mean duration of Phase I was 151 seconds (SD 770, median 60 seconds, n=141 events), and for the second phase, the mean duration was 18.2 minutes, with median of 11.4 minutes, which included the terminal recovery period.

In Set B, recovery rates were determined from 141 separate events in the individual Off intervals, and are in dimensionless units per second. Phase I recovery was at a mean rate of 0.00322 (SD 0.00591). Average recovery rates determined for Phase II were, 59.7 × 10−6 (SD 116 x 10−6). Recovery rate in Phase I was not affected by any of the input variables,. Phase II recovery rate was affected by Frequency of KHFAC (p<0.015) and cumulative KHFAC (p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Our experiments have shown three categories of nerve response to prolonged KHFAC conduction block. These categories are identified by the rate at which normal nerve conduction is restored following the cessation of KHFAC delivery. It is entirely possible that different underlying mechanisms are at work in each of these different categories.

Immediate recovery was observed when KHFAC block was delivered to a previously unblocked nerve for periods less than approximately 10 minutes. Fast recovery was characterized by full peak force recovery within approximately one to two minutes. The peak force could recover more than 50% of full range in this duration. This type of recovery appeared after KHFAC was delivered for periods over 10 minutes or was delivered repeatedly for shorter periods. Slow recovery took place over several minutes to hours. Slow recovery could involve the entire force range. Peak force could reduce to 0% (complete conduction block) and recover to 100% over the course of an hour. Slow recovery only appeared after KHFAC block has been delivered for many tens of minutes. The appearance of slow recovery was dependent on the duty cycle of KHFAC block. Once the slow recovery was complete, it may not appear again after KHFAC reapplication. It may be necessary for KHFAC block to be delivered again for many minutes before it reappears.

The ratio of evoked muscle force from proximal stimulus to the force from distal stimulus (PS/DS) is a measure of conduction loss under the block electrode, independent of changes at the motor point and in muscle metabolism. Reversibility is measured using the peak of the force twitch generated by maximal stimulation of the nerve with proximal stimulation. The peak force being recorded prior to delivery of KHFAC block. The ratio of post-block peak force to pre-block peak force provides a direct measure of the degree and rate of conduction loss and recovery. A ratio of 1.0 represents equivalent excitation by both PS and DS, indicating equivalent conduction before and after block. When block is delivered for periods of seconds, up to approximately 10 minutes, this ratio is 1.0 within one to three seconds after cessation of block.

During the experiments conducted here, we did not observe any permanent conduction loss in the nerves or permanent decrease in peak force as a result of KHFAC delivery. Therefore, the effect of prolonged KHFAC on the nerve could be described as a “stun” effect in the sense that the nerve is briefly stunned, but not damaged. The principle parameter influencing COBE in this study, was the cumulative time of KHFAC delivery. Secondary parameters were KHFAC frequency and amplitude (higher values resulted in more rapidly developing COBE).

A very pertinent issue in nerve conduction loss after KHFAC is contamination of the stimulus signal with DC from the stimulation apparatus. It has been observed that commonly used signal generators, both current and voltage controlled, can produce a DC offset on the generated KHFAC (Franke, Bhadra et al. 2014). Such unintentional DC contamination of KHFAC signals could produce temporary conduction loss due to prolonged depolarization. This could also lead to undesirable electrochemical changes in the stimulation electrodes. It is important to test for DC contamination of the signal output for KHFAC nerve block experiments. It is possible that in some of the experiments noted below, the high frequency signal may have been inadvertently contaminated by a DC output.

A ‘carry-over’ effect was reported in rat Vagus nerve with application of a 5 kHz waveform at amplitudes up to 8 mA (Waataja et al. 2011). Compound action potentials (CAP) were recorded to verify lack of nerve conduction after delivering the 5 kHz for one minute. Immediately after end of delivery of the 5 kHz, nerve conduction was found to be partially blocked for periods of five or more minutes, depending on the amplitude of the 5 kHz waveform. The appearance of such a carryover effect after only 1 min contrasts with experiments in rat and cat sciatic, where immediately reversibility could be maintained for periods of up to 30 min (Bhadra et al. 2012). These differences may be because of differing responses between motor and autonomic nerve fibers, or they could be due to differences in experimental apparatus and waveform parameters.

Application of 5 kHz AC, rectangular waveforms, on isolated frog sciatic nerve using Ag/AgCl electrodes has been reported to show a depression in nerve conduction (Liu et al, 2011). They reported slowed conduction through the blocked region after HFAC application of 5 and 60 sec. “A time of at least 1 min was needed for recovery for a 5s HF stimulation of 5 kHz at threshold block amplitude”. They observed a difference in the recovery of CAP amplitude and conduction velocity with differences in HFAC amplitude. The amplitude of the recorded CAP recovered slower than the conduction velocity in the first 30 secs after HFAC application (Liu et al. 2013).

Cuellar et al. 2013 noted a ‘carry-over’ effect immediately after the cessation of KHFAC in the block of dorsal nerve roots in rats and goats but recognized that the block during this period appeared to underestimate the percentage of block during KHFAC. They reported that a complete recovery of nerve response typically occurred within 2–3 min, but that some neurons remained suppressed for up to 10 min. They suggested that the time to recovery was a function of KHFAC duration, “with longer recovery times observed after longer suppression times”.

Persistence of conduction block following 5 or 10 kHz stimulation was also reported in a frog sciatic nerve preparation (Yang et al, 2016) with foot force monitoring. They observed significant post-stimulation block of conduction with high frequency biphasic stimulation of 4–5 minutes. They reported two recovery phase, the first of complete block and a second of partial recovery, dependent on the duration and intensity of high-frequency biphasic stimulation, with no dependence on stimulus frequency. A temporal effect may have been a contributing factor as stimulus was applied in an increasing order of the stimulation durations.

There is, at present, no theoretical nerve model that predicts the presence of COBE. We believe that COBE is likely due to a local depletion of metabolic products critical for action potential conduction, and that different mechanisms are at work for fast-recovery and slow-recovery COBE. The time durations of cumulative KHFC application are in the same ranges as anoxic conduction loss in myelinated nerve fibers (Waxman and Kocsis, 1995). As an example, cellular ATP production is non-linearly coupled to the transmembrane potential (Δψm) of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Even small changes in Δψm affect ATP production severely (Oliveira 2012) . This in turn can hinder the sodium-potassium pump (Na-K ATPase), leading to conduction failure. This may be the mechanism for the fast-recovery COBE. Electric fields from high frequency waveforms (or very narrow pulses) of sufficient magnitude, can penetrate the plasmalemma and downgrade Δψm (Mi, Sun et al. 2007). This is analogous to the mechanism used to target molecules into the cell nucleus by electroporation. Slow-recovery COBE may be connected to Ca++ mitochondrial mechanisms, which have a dynamic response time in the same order of magnitude. We anticipate exploring this area further in future.

In applications where quick reversibility of conduction following KHFAC block is critically important, measures may have to be taken to reduce the effects of COBE. Choice of KHFAC frequencies in the lower kHz ranges may allow increase in application time. On the other hand, COBE may be utilized to achieve prolonged conduction block durations without continued energy expenditure for stimulation. It can also be formulated to provide predetermined degrees of block, to modulate signal traffic in selected nerves for extended time durations.

The presence of COBE is disadvantageous if KHFAC block is to be used to control conditions like spasticity, where rapid reversibility is highly desirable. It should be noted, however, that COBE could provide a significant advantage where a slow recovery from block is not an impediment, e.g. in chronic pain applications. COBE may be useful for longer durations of conduction block without the need for continuous application of KHFAC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NINDS R01-NS-074149 and R01-NS-074149, NIBIB R01-EB-002091.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Kevin Kilgore and Niloy Bhadra have equity ownership in Neuros Medical Inc.

References

- Ackermann DM, Jr, Ethier C, Foldes EL, Oby ER, Tyler D, Bauman M, Bhadra N, Miller L, Kilgore KL. Electrical conduction block in large nerves: high-frequency current delivery in the nonhuman primate. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(6):897–899. doi: 10.1002/mus.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra N, Kilgore KL. High-frequency electrical conduction block of mammalian peripheral motor nerve. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32(6):782–790. doi: 10.1002/mus.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra N, Vrabec T, Bhadra N, Kilgore KL. Response of peripheral nerve to highfrequency alternating current (HFAC) nerve block applied for long durations. Paper presented at Neural Interface Conference; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boger A, Bhadra N, Gustafson KJ. Bladder voiding by combined high frequency electrical pudendal nerve block and sacral root stimulation. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27(5):435–439. doi: 10.1002/nau.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar JM, Alataris K, Walker A, Yeomans DC, Antognini JF. Effect of High-Frequency Alternating Current on Spinal Afferent Nociceptive Transmission. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface. 2013;16(4):318–327. doi: 10.1111/ner.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldes EL, Ackermann DM, Bhadra N, Kilgore KL, Bhadra N. Design, fabrication and evaluation of a conforming circumpolar peripheral nerve cuff electrode for acute experimental use. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;196(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke M, Bhadra N, Bhadra N, Kilgore KL. Importance of avoiding unintentional DC in KHFAC nerve block applications. EEE EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Franke M, Bhadra N, Bhadra N, Kilgore K. Direct current contamination of kilohertz frequency alternating current waveforms. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;232:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore KL, Bhadra N. Nerve conduction block utilising high-frequency alternating current. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2004;42(3):394–406. doi: 10.1007/BF02344716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore KL, Bhadra N. Reversible nerve conduction block using kilohertz frequency alternating current. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(3):242–255. doi: 10.1111/ner.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zhu L, Tang H, Qiu T. Biomedical Engineering and Informatics (BMEI), 2011 4th International Conference on. Vol. 3. IEEE; 2011. Effects of high frequency electrical stimulation on nerve’s conduction of action potentials; pp. 1308–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zhu L, Sheng S, Sun L, Zhou H, Tang H, Qiu T. Post stimulus effects of high frequency biphasic electrical current on a fibre’s conductibility in isolated frog nerves. Journal of neural engineering. 2013;10(3):036024. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/3/036024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Y, Sun C, Yao C, Li C, Mo D, Tang L, Liu H. Effects of steep pulsed electric fields (SPEF) on mitochondrial transmembrane potential of human liver cancer cell. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:5815–5818. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4353669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira JMA. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Dynamics. In: Reeve AK, Krishnan KJ, Duchen MR, Turnbull DM, editors. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Dynamics. London: Springer-Verlag; 2012. pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Waataja JJ, Tweden KS, Honda CN. Effects of high-frequency alternating current on axonal conduction through the vagus nerve. Journal of neural engineering. 2011 Oct;8(5):056013. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/5/056013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. The axon: structure, function, and pathophysiology. Oxford University Press; USA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Xiao Z, Wang J, Shen B, Roppolo JR, de Groat WC, Tai C. Post-stimulation block of frog sciatic nerve by high-frequency (kHz) biphasic stimulation. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11517-016-1539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]