Abstract

Vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-ATPases; V1Vo-ATPases) are rotary-motor proton pumps that acidify intracellular compartments and, in some tissues, the extracellular space. V-ATPase is regulated by reversible disassembly into autoinhibited V1-ATPase and Vo proton channel sectors. An important player in V-ATPase regulation is subunit H, which binds at the interface of V1 and Vo. H is required for MgATPase activity in holo-V-ATPase but also for stabilizing the MgADP-inhibited state in membrane-detached V1. However, how H fulfills these two functions is poorly understood. To characterize the H–V1 interaction and its role in reversible disassembly, we determined binding affinities of full-length H and its N-terminal domain (HNT) for an isolated heterodimer of subunits E and G (EG), the N-terminal domain of subunit a (aNT), and V1 lacking subunit H (V1ΔH). Using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and biolayer interferometry (BLI), we show that HNT binds EG with moderate affinity, that full-length H binds aNT weakly, and that both H and HNT bind V1ΔH with high affinity. We also found that only one molecule of HNT binds V1ΔH with high affinity, suggesting conformational asymmetry of the three EG heterodimers in V1ΔH. Moreover, MgATP hydrolysis–driven conformational changes in V1 destabilized the interaction of H or HNT with V1ΔH, suggesting an interplay between MgADP inhibition and subunit H. Our observation that H binding is affected by MgATP hydrolysis in V1 points to H's role in the mechanism of reversible disassembly.

Keywords: vacuolar ATPase, protein assembly, protein conformation, biophysics, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), biolayer interferometry, MgADP inhibition, protein-protein interaction, reversible disassembly, V1-ATPase

Introduction

Vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-ATPases2; V1Vo-ATPases) are ATP-dependent proton pumps present in all eukaryotic cells. Typically, the V-ATPase is localized on the endomembrane system where the enzyme acidifies intracellular compartments, a process essential for pH homeostasis, protein trafficking, endocytosis, hormone secretion, mTOR signaling, and lysosomal degradation (1). The V-ATPase is also present on the plasma membrane of certain specialized cells such as osteoclasts, renal cells, the vas deferens, and the epididymis where the enzyme acidifies the extracellular environment. V-ATPase's proton pumping activity has been linked to numerous human diseases including osteoporosis and -petrosis (2, 3), renal tubular acidosis (4), male infertility (5), neurodegeneration (6), diabetes (7), viral infection (8), and cancer (9), making the enzyme a valuable drug target (10, 11).

The V-ATPase shares a similar architecture and catalytic mechanism with the F-ATP synthase such that it consists of a water-soluble ATP-hydrolyzing machine (V1) and a membrane-integral proton channel (Vo), which are structurally and functionally coupled via a central stalk and multiple peripheral stalks (12–14). The subunit composition of the V-ATPase from yeast is A3B3CDE3FG3H for the cytosolic V1 (15) and ac8c′c″def for the membrane-integral Vo (16, 17). The subunit architecture of the V-ATPase has been studied by electron microscopy (EM) and several low- to intermediate-resolution reconstructions of bovine, yeast, and insect V-ATPase are available, which, together with X-ray crystal structures of individual subunits and subcomplexes of yeast V-ATPase and bacterial homologs, have provided a detailed model of the subunit architecture of the eukaryotic V-ATPase complex (17–22) (see Fig. 1A). V-ATPase is a rotary-motor enzyme (14). ATP hydrolysis in the catalytic A3B3 hexamer is coupled to rotation of the proteolipid ring (c8c′c″) via a central rotor made of subunits D, F, and d with concurrent proton translocation at the interface of the proteolipid ring and the C-terminal domain of subunit a (aCT). During rotary catalysis, the motor is stabilized by a peripheral stator complex consisting of three peripheral stalks constituted by heterodimers of subunits E and G (hereafter referred to as EG1–3) that connect the A3B3 hexamer to the N-terminal domain of the membrane-bound a subunit (aNT) via the single-copy “collar” subunits H and C (19, 21) (see Fig. 1A). Three intermediates (referred to as rotational states 1–3), in which the central rotor is spaced 120° relative to the catalytic hexamer and subunit a, have been visualized in the yeast enzyme by cryo-EM (21).

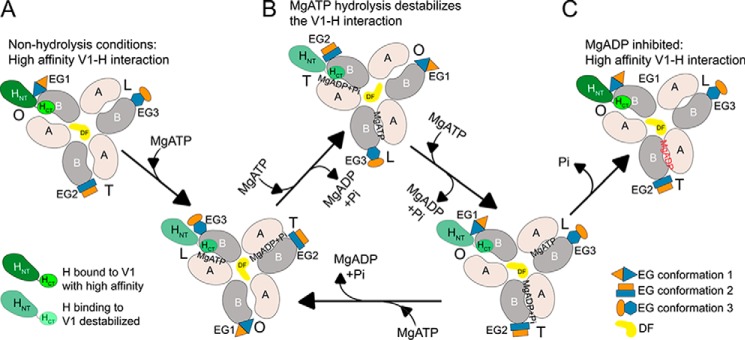

Figure 1.

Schematic of yeast V-ATPase regulation by reversible disassembly. A, subunit architecture of holo-V-ATPase. The V1 and Vo sectors are assembled and form an active enzyme. B, upon glucose deprivation, the V1 and Vo sectors disengage, and the activity of both sectors is silenced. The subunits of the peripheral stator that form the V1–Vo interface are shown in color. prox., proximal; dist., distal.

Unlike the related F-ATP synthase, eukaryotic V-ATPase is regulated by a unique mechanism referred to as reversible disassembly wherein, upon receiving cellular signals, V1 dissociates from Vo, and the activity of both sectors is silenced (22–26) (see Fig. 1B). Reversible disassembly was first observed in yeast (27) and insects (28), but the process has recently also been observed in higher animals including human (29–32). Studies in yeast have shown that, during enzyme disassembly, subunit C is released into the cytosol by an unknown mechanism and reincorporated during reassembly (27). Because of regulation of the V-ATPase by reversible disassembly, the peripheral stator subunit interactions at the V1–Vo interface draw particular attention as they must be sufficiently strong to withstand the torque generated during ATP hydrolysis, but at the same time they must be vulnerable enough to allow breaking on a timescale for reversible disassembly to occur efficiently.

We previously characterized the interaction of the collar subunit C with EG and aNT and found that although the head domain of C (Chead) binds EG with high affinity (Chead–EG3; see Fig. 1A), its foot domain (Cfoot) and EG both interact weakly with aNT, resulting in a high-avidity ternary interface (EG2–aNT–Cfoot) in holo-V-ATPase (33, 34). Another collar subunit at the V1–Vo interface is subunit H, and although deletion of C prevents stable assembly of V1 and Vo (35), deletion of H results in the formation of a V1Vo(ΔH) complex that lacks MgATPase and proton-pumping activities (36, 37). Moreover, although C is released into the cytosol upon disassembly of V1Vo, H remains stably associated with V1 (Fig. 1B). The crystal structure of H revealed that it consists of a larger N-terminal (HNT) and smaller C-terminal domain (HCT) connected by a short linker (38). Previous functional characterization of HNT and HCT suggested that, although HNT is required for MgATPase activity in V1Vo, HCT has a dual function in that it is required for both coupling of V1's ATPase activity to proton pumping in V1Vo (37) and inhibition of MgATPase activity in membrane-detached V1 (39). The dual role and functional separation of HNT and HCT along with differences in regulatory function compared with C are not well understood and prompted the analyses of the interactions of H, HNT, and HCT with its binding partners in V1 and Vo. We therefore used recombinant H, HNT, and HCT for quantification of their interactions with purified EG, aNT, and V1 lacking subunit H (V1ΔH) using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and biolayer interferometry (BLI). We found that HNT binds no more than one of the three EGs on V1ΔH and that the affinity of this interaction is ∼40-fold higher than that between HNT and isolated EG, suggesting that HNT prefers a particular conformation of EG on V1. We further found that full-length H interacts with V1ΔH with an ∼70-fold higher affinity than HNT, indicative of a significant contribution of HCT to the binding energy. Furthermore, we show that MgATP hydrolysis–driven conformational changes in the catalytic A/B pairs, the central rotor (DF), and the peripheral stalks (EG) destabilize the V1–H interaction until inhibitory MgADP is trapped in a catalytic site. The findings are discussed in context of the mechanism of V-ATPase regulation by reversible disassembly.

Results

Expression, purification, and biophysical characterization of H, HNT, HCT, and aNT(1–372)

To understand the role of the V1–Vo interface in the mechanism of reversible disassembly, our laboratory has previously characterized the interactions among Chead, Cfoot, EG, and aNT (33, 34). Interactions involving subunit H, however, are yet to be quantified. Pulldown and yeast two-hybrid assays have shown that H is able to bind the N-terminal region of subunit E (40). In addition, EM and crystal structures of V1Vo and V1, respectively, show HNT bound to one of the three EG peripheral stalks (EG1; see Fig. 2, A and B), whereas HCT is seen to either rest on the coiled-coil middle domain of aNT (in V1Vo; Fig. 2A) or at the bottom of the A3B3 hexamer (in autoinhibited V1) (Fig. 2B) (21, 22). To analyze the interactions of H within the enzyme in more detail, we expressed H, HNT, and HCT separately and quantified their interactions with recombinant EG, aNT, and V1ΔH purified from yeast.

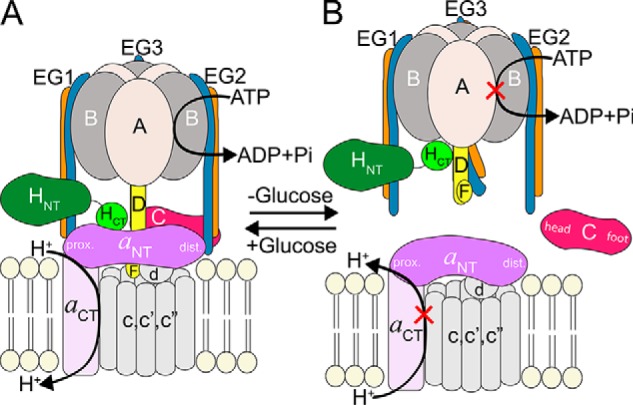

Figure 2.

Binding interactions of subunit H in holo-V1Vo and autoinhibited V1-ATPase. A, in V1Vo (Protein Data Bank code 3J9U) (21), HNT (dark green) is bound to EG1 (blue/orange), and HCT (light green) is in contact with aNT (purple). B, in membrane-detached and autoinhibited V1 (Protein Data Bank code 5D80) (22), the contact between HNT and EG1 is preserved, but HCT undergoes a ∼150° rotation to bind the bottom of the A3B3 hexamer and the rotor subunit D. The large conformational change in HCT is depicted by the positions of the C-terminal α-helix (magenta) and the inhibitory loop (red) in holo-V1Vo versus autoinhibited V1-ATPase.

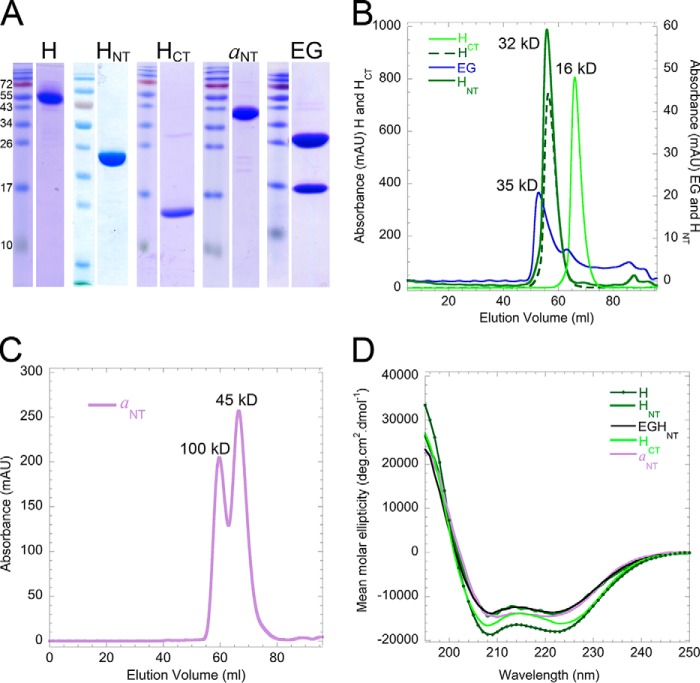

Full-length H, HNT (residues 1–354), HCT (residues 352–478), and aNT (residues 1–372) were expressed in Escherichia coli as N-terminal fusions with maltose-binding protein (MBP). After amylose affinity capture, fusions were cleaved, and MBP was removed by ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography, resulting in purified subunits and subunit domains (Fig. 3A). All proteins eluted near their expected molecular masses on size exclusion chromatography except aNT(1–372), which exists in a dimer–monomer equilibrium as described previously (26, 34) (Fig. 3, B and C). Consistent with available structural information, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy revealed a high degree of α-helical secondary structure, suggesting proper folding of the recombinant polypeptides (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Purification and characterization of recombinant V-ATPase subunits and their domains. A, SDS-polyacrylamide gel of purified recombinant proteins used in the interaction studies described here. B, gel filtration elution profiles of H, HNT, HCT, and EG on a 1.6 × 50-cm Superdex 75 column. H, HNT, and HCT elute in single symmetric peaks (with molecular weights indicated next to the peaks), suggesting monomeric and monodisperse proteins. The majority of EG elutes as a single peak with some residual excess G subunit at larger elution volumes. C, aNT(1–372) elutes on a 1.6 × 50-cm Superdex 200 column in two overlapping peaks corresponding to the dimer and monomer as described before. D, CD spectra of H, HNT, HCT, aNT, and the EGHNT complex recorded from 250 to 195 nm. The minima at 222 and 208 nm indicate α-helical secondary structure. deg, degrees; mAU, milliabsorbance units.

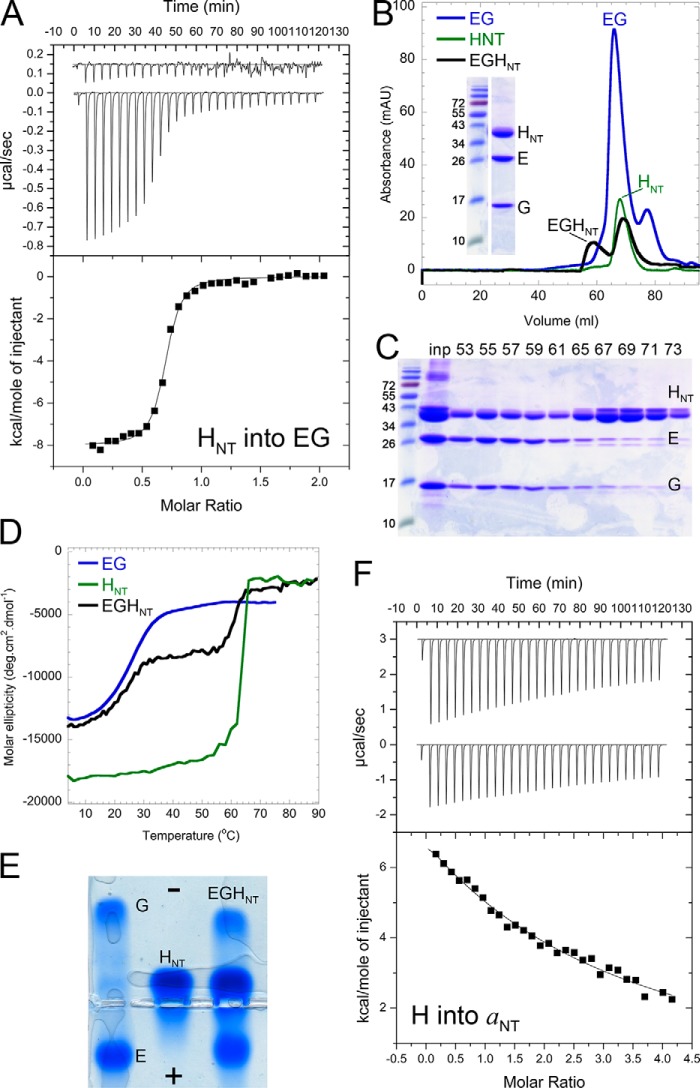

Interaction of HNT with EG

We previously established that binding of C (or Chead) to isolated EG occurs with high affinity and that the interaction greatly stabilizes EG (33). To further characterize the interactions at the V1–Vo interface, we set out to determine the affinity of the HNT–EG interaction using ITC. Titration of HNT into EG was exothermic, and the binding curve was fit to a single-binding-site model, revealing a Kd of the interaction of 187 nm. The binding enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) were −8 kcal/mol and 2.5 cal/(mol·K), respectively, with a concomitant free energy change (ΔG) of ∼−36 kJ/mol (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the ITC titration, size exclusion chromatography of a mixture of EG and an excess of HNT resulted in the formation of a ternary HNT–EG complex (Fig. 4, B and C), and taken together, the data show that HNT forms a stable complex with the EG heterodimer. Previously, we found that the EG's N-terminal right-handed coiled coil is thermally labile with a Tm of ∼25 °C (Fig. 4D, blue trace) (29) and that the Tm of EG is increased by about 10 °C upon complex formation with C(head) (33). To test whether HNT binding has a similar stabilizing effect on EG, thermal unfolding of the individual proteins and EGHNT complex was monitored by recording the CD signal at 222 nm as a function of temperature. The data show that isolated HNT unfolds with an apparent Tm of ∼63 °C (Fig. 4D, green trace). The thermal unfolding curve of the EGHNT complex showed two transitions, one at 25 °C and one at 64 °C, suggesting that the stability of EG is not increased upon HNT binding (Fig. 4D, black trace). Moreover, as also shown previously (33), isolated EG heterodimer dissociates during native agarose gel electrophoresis, whereas in presence of Chead the three proteins migrate as a heterotrimeric complex in the electric field. However, consistent with the thermal unfolding data, a complex of EGHNT did not comigrate on the native gel but ran as three separate species (Fig. 4E). Therefore, although both Chead and HNT form a stable complex with EG, the nature of the two interactions are strikingly different.

Figure 4.

Interaction of HNT with the EG heterodimer and H with aNT. A, isothermal titration calorimetry of the interaction between HNT and EG. HNT was titrated into EG (top panel, lower trace) or buffer only (top panel, top trace), and the heat associated with the interaction was measured at 10 °C in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm TCEP, pH 8. The area under the peaks in the top panel was integrated and plotted as kcal/mol of HNT as a function of binding stoichiometry in the bottom panel. These data were fit using a one-site binding model resulting in a Kd of 187 nm with ΔH and ΔS values of −8 kcal/mol and 2.5 cal/(mol·K), respectively, resulting in a ΔG of the interaction of ∼−36 kJ/mol. A representative of three separate titrations is shown. B, the ITC cell content was subjected to gel filtration on a 1.6 × 50-cm Superdex 200 column (black trace). The individual gel filtration elution profiles of HNT and EG using the same column are shown in green and blue, respectively. C, SDS-PAGE of gel filtration fractions from the ITC cell content. EGHNT elutes at higher molecular mass with excess HNT in a well separated peak. The shift of the EGHNT peak (compared with EG or HNT) toward higher molecular weight indicates complex formation. The inset in B shows the EGHNT peak fraction (fraction 55) from the SDS-PAGE gel of the ITC cell content shown in C. D, thermal unfolding of HNT, EG, and EGHNT monitored by recording the CD signal at 222 nm with increasing temperature. HNT shows highly cooperative unfolding with an apparent Tm of ∼63 °C (green). EG has an apparent Tm of ∼25 °C (data taken from Ref. 33). The EGHNT complex shows two unfolding transition with Tm values similar to the those observed for the individual proteins, suggesting that HNT binding to EG does not stabilize the EG heterodimer. E, native agarose gel electrophoresis of EG heterodimer, HNT, and EGHNT. 30 μg of purified EG, 30 μg of purified HNT, and a mixture of equimolar amounts of HNT and EG (total 60 μg) were loaded. Unlike binding of Chead to EG (33), binding of HNT does not appear to stabilize EG under these conditions. F, isothermal titration calorimetry of the interaction between aNT and H. H was titrated into aNT (top panel, lower trace) or buffer (top panel, top trace), and the heat associated with the interaction was measured at 10 °C in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm TCEP, pH 8. Subtracting the heat of dilution of titration of H into buffer revealed an endothermic binding reaction. Fitting the data (bottom panel) to a one-site binding model with a fixed n = 1 allowed an estimate of the Kd of ∼130 μm. A representative titration from two repeats is shown. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

Interaction of H with aNT

Prior work from our laboratory has shown that the EG2–aNT–Cfoot junction at the V1–Vo interface (Fig. 1A) is formed by multiple low-affinity interactions, and we reasoned that the sum of these interactions provides a high-avidity binding site between V1 and Vo that could be targeted for regulated disassembly (34). Another interaction that is seen in EM reconstructions of the intact V-ATPase, and that must be broken and reformed during reversible disassembly, is between H and aNT (Figs. 1A and 2A). To estimate the affinity between H and aNT, we performed ITC experiments by titrating H into aNT(1–372) (Fig. 4F). Subtracting the heat generated from diluting H into buffer from the heat generated from titrating H into aNT(1–372) revealed a weak endothermic binding reaction between the two proteins. Fitting the data to a one-site binding model revealed a Kd of 135 μm and ΔH, ΔS, and ΔG values of 4 kcal/mol, 36.1 cal/(mol·K), and −26 kJ/mol, respectively. Consistent with our ITC data, a mixture of H and aNT eluted at the same volumes as the individual proteins on size exclusion chromatography (Fig. S1). The low-affinity interaction between H and aNT supports our existing model that V1 binds Vo via several low-affinity interactions that, taken together, result in a high-avidity interface in assembled V1Vo.

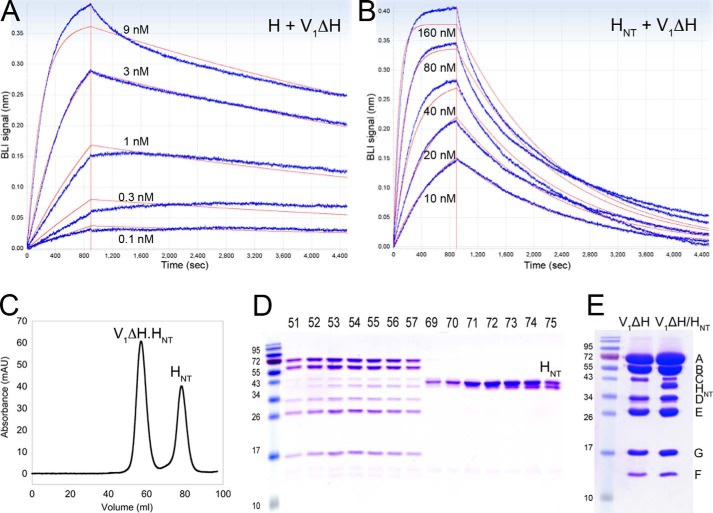

Interaction of V1ΔH with H, HNT, and HCT characterized by BLI

Previous experiments showed that H remains bound to V1 even at the low concentrations used in enzyme essays (e.g. ∼15 nm) (22, 25, 39) and under the conditions of electrospray ionization used for native MS (15). Although the data so far have shown that the affinity of HNT for EG as measured using ITC is moderately high, the observed Kd of ∼0.2 μm (Fig. 4A) could not explain the above observations, which means that the interaction of H with V1 has to be much stronger (39). We therefore wished to determine the affinity of full-length H as well as HNT and HCT for V1ΔH. The interaction between V1ΔH and MBP-tagged H, HNT, and HCT was quantified using BLI. MBP-tagged proteins were immobilized on anti-mouse Fc capture (AMC) biosensors using an anti-MBP antibody, and the rate of association and dissociation of V1ΔH was measured hereafter. The slow dissociation of MBP-tagged H, HNT, and HCT from the anti-MBP antibodies was subtracted from the V1ΔH dissociation rates for analysis of the kinetic data. BLI experiments for measuring association and dissociation kinetics between V1ΔH and MBP-H/HNT were conducted at five different V1ΔH concentrations, and the resulting association and dissociation curves were fit to a global single-site binding model (Fig. 5, A and B). Analysis of the data for MBP-H and MBP-HNT revealed Kd values of ∼65 pm (Fig. 5A) and ∼4.5 nm (Fig. 5B), respectively. We also tested the binding of V1ΔH to MBP-HCT, but we were not able to determine a Kd as there was no measurable association at low V1ΔH concentrations (<100 nm), and higher V1ΔH concentrations (e.g. 1 μm) resulted in nonspecific binding to the BLI sensors (data not shown). Overall, the interaction of HNT with EG as part of V1ΔH was ∼40-fold tighter when compared with the interaction between HNT and isolated EG (as measured using ITC; Fig. 4A), suggesting that the conformation of EG on V1ΔH is more favorable for HNT binding than the conformation(s) of isolated EG. In addition, although we could not detect an interaction between HCT and V1ΔH under the conditions of BLI, a ∼70-fold higher affinity of V1ΔH for H as compared with HNT suggests a significant contribution of HCT to the V1–H interaction. From our ITC and BLI experiments, we infer that the binding interaction between HNT and EG allows HCT to switch conformations so that it can either bind aNT (in V1Vo) or subunits B and D (in V1) to efficiently carry out its dual role in reversible disassembly.

Figure 5.

Interaction of H and HNT with V1ΔH. A, the affinity of the interaction between H and V1ΔH was determined using BLI at 22 °C in BLI buffer. Association and dissociation sensorgrams from five different concentrations of V1ΔH (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, and 9 nm) are shown in blue. The data were globally fit (traces in red) to reveal a Kd of ∼65 pm. B, a similar experiment was conducted to analyze the interaction between HNT and V1ΔH. HNT was dipped in 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 nm V1ΔH followed by buffer to generate association and dissociation curves, respectively (blue). The data were globally fit (red traces) to reveal a Kd of ∼4.5 nm. C, V1ΔH was incubated with a 5-fold excess of HNT, and the mixture was resolved on a 1.6 × 50-cm Superdex 200 column. D, SDS-PAGE of gel filtration fractions. The higher molecular weight peak showed V1ΔH in complex with HNT with the lower molecular weight peak corresponding to excess HNT. E, approximately equimolar amounts of V1ΔH and V1ΔH in complex with HNT were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The staining intensity of the HNT compared with the single-copy subunit D band in the V1(ΔH)HNT complex suggests that V1ΔH binds no more than one copy of HNT with high affinity. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

V1ΔH binds no more than one HNT

Because V1ΔH contains three EG heterodimers, we wished to determine whether all three or only one of the EGs can bind HNT. Purified V1ΔH was mixed with a 5-fold molar excess of HNT followed by size exclusion chromatography. Under these conditions, some HNT coeluted with V1ΔH with the excess HNT eluting from the column as a separate, lower molecular weight peak (Fig. 5, C and D). The V1(ΔH)HNT complex was concentrated, and approximately equal amounts of V1ΔH and V1(ΔH)HNT were resolved using SDS-PAGE. The staining of HNT in the purified V1(ΔH)HNT complex was similar to that of single-copy subunits in the V1 complex (for example subunit D), indicating that no more than one copy of HNT bound to V1ΔH (Fig. 5E). Therefore, although there are three EGs in V1ΔH, only one of these is in a conformation that is able to bind HNT with high affinity, highlighting the conformational asymmetry of the peripheral stalks.

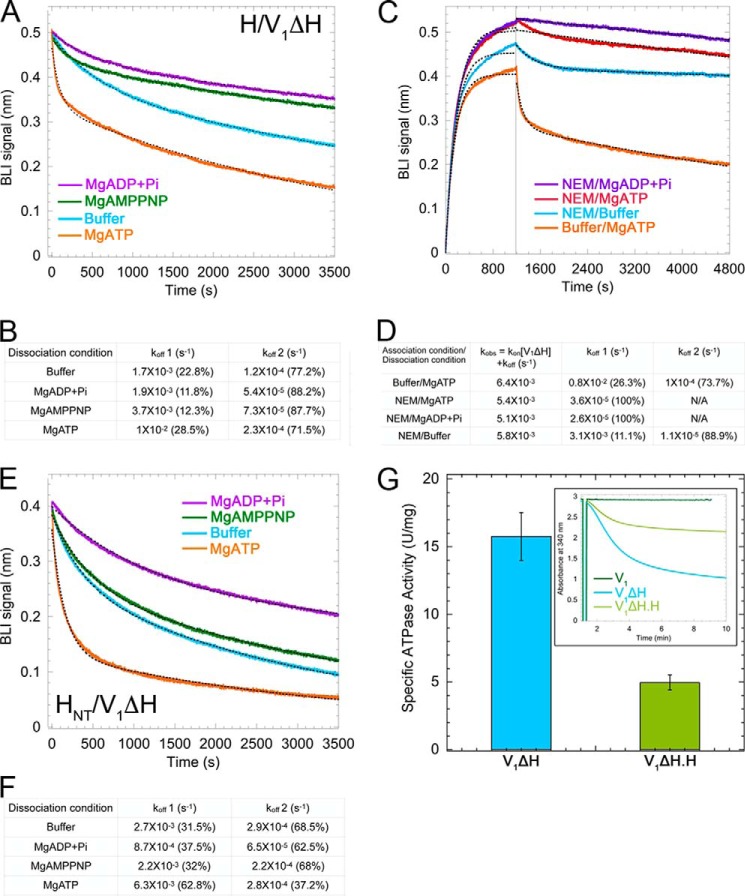

The interaction of H with V1ΔH is destabilized upon MgATP hydrolysis

The preference of HNT for one of three EGs suggested that the asymmetry of the peripheral stalks originates in the catalytic core (A3B3DF) of V1. Upon MgATP hydrolysis, however, the conformational changes of the catalytic sites from open to loose to tight drive counterclockwise rotation of the central rotor along with cyclic structural changes in the peripheral stalks from EG1 to EG3 to EG2 (41). In addition, based on the structure and nucleotide occupancy of the autoinhibited V1 sector, our laboratory suggested that HCT inhibits V1-ATPase activity by preferentially binding to an open catalytic site, consequently maintaining inhibitory MgADP in the adjacent closed catalytic site (22). Taken together, HNT's preference for EG1, as well as HCT's role in MgADP inhibition, indicated a potential interplay between the nucleotide occupancy of the catalytic sites and the interaction of V1ΔH with H. To probe the effect of nucleotides on the interaction of H with V1ΔH, we again used BLI. V1ΔH was bound to immobilized MBP-H, and the sensor was then dipped in wells containing buffer or buffer with 1 mm MgATP, MgADP + Pi, or MgAMPPNP. Interestingly, in the presence of MgATP, a biphasic dissociation curve was observed with an initial dissociation rate that was ∼6 times faster than the rate in buffer alone (Fig. 6, A and B). However, only ∼25% of the bound V1ΔH dissociated with a fast rate with the remaining 75% coming off the sensor at a rate similar to the dissociation rate in buffer (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, a relatively slower rate of dissociation was observed in the presence of MgADP + Pi and MgAMPPNP.

Figure 6.

The interaction between subunit H and V1ΔH is destabilized upon MgATP hydrolysis. A, sensorgrams of V1ΔH dissociation from immobilized H subunit in the absence (blue) and presence of 1 mm nucleotides (MgADP + Pi, purple; MgAMPPNP, green; MgATP, orange). A representative from at least two independent experiments is shown. B, off-rates determined from fitting the sensorgrams from A to dual-exponential equations. C, sensorgrams of association and dissociation of NEM-inhibited V1ΔH to and from immobilized H subunit in the absence or presence of 1 mm nucleotides (association of NEM-modified V1ΔH in buffer/dissociation in MgADP + Pi, purple; association of NEM-modified V1ΔH in buffer/dissociation in MgATP, red; both association and dissociation of NEM-modified V1ΔH in buffer, blue; association of unmodified V1ΔH in buffer/dissociation in MgATP, orange). A representative from at least two independent experiments is shown. D, observed on-rates (kobs) and off-rates obtained from fitting the sensorgrams in C to single- and dual-exponential equations, respectively. E, sensorgrams of V1ΔH dissociation from immobilized HNT in the absence (blue) and presence of 1 mm nucleotides (MgADP + Pi, purple; MgAMPPNP, green; MgATP, orange). A representative from at least two independent experiments is shown. F, off-rates determined from fitting the sensorgrams from E to dual-exponential equations. G, average specific activities of V1ΔH and V1(ΔH)H plotted ±S.E. (error bars) from two independent purifications. Inset, raw data for activity measurement using an ATP-regenerating assay (22). V1-ATPase activity is determined by monitoring a decrease in A340 as a function of time. Traces for WT V1, V1ΔH, and V1(ΔH)H are shown in dark green, blue, and light green, respectively. N/A, not applicable.

The destabilization of the V1–H interaction upon MgATP hydrolysis came as a surprise to us as the H subunit is known to inhibit V1-ATPase activity (22, 25, 39). To confirm that the fast dissociation of V1ΔH from MBP-H in wells containing MgATP was specifically due to MgATP binding to V1's catalytic sites, we conducted a similar BLI experiment using V1ΔH treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). It is known that NEM modification of a catalytic-site cysteine residue prevents binding of nucleotides (42). NEM-treated and untreated V1ΔH were bound to MBP-H immobilized on sensors and then dipped in wells containing MgATP, MgADP + Pi, or buffer (Fig. 6, C and D). We found that NEM-treated V1ΔH no longer showed a fast dissociation rate when dipped in MgATP-containing wells, suggesting that MgATP binding to the catalytic sites caused destabilization of the V1–H interaction. However, if the above mentioned fast dissociation rate was a result of only MgATP binding, but not hydrolysis, we should have observed fast dissociation in the presence of MgAMPPNP, the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog. MgAMPPNP, however, had no effect on the V1ΔH dissociation rate (Fig. 6A, green trace). Taken together, the BLI experiments with NEM-modified V1ΔH and in the presence of MgAMPPNP suggest that it is MgATP binding and hydrolysis that destabilize the V1–H interaction. Because both HNT and HCT contribute to the interaction of H with V1ΔH, we also measured the off-rate of V1ΔH from immobilized MBP-HNT and found that the HNT–V1ΔH interaction was also destabilized upon MgATP hydrolysis as seen for H and V1ΔH (Fig. 6, E and F).

To verify that V1ΔH bound to H was capable of transient turnover, we purified V1ΔH, incubated it with an excess of H, and resolved the mixture using size exclusion chromatography (Fig. S2). We found that V1ΔH reconstituted with H (V1(ΔH)H) showed ∼4.9 ± 0.55 units/mg of MgATPase activity, which was ∼30% of the activity of V1ΔH (15.75 ± 1.7 units/mg) (Fig. 6G and Ref. 22). Considering the high-affinity interaction between V1ΔH and H with a Kd of ∼65 pm, we expected stoichiometric amounts of H in the V1(ΔH)H reconstituted complex. However, to exclude the possibility that the observed MgATPase activity in the V1(ΔH)H complex was due to substoichiometric binding of H, we performed a pulldown experiment in which a 10-fold molar excess of MBP-H bound to amylose resin was used to capture V1ΔH (Fig. S3). Although some MBP-H and V1ΔH appeared in the supernatant and washes of the amylose resin, most of the MBP-H eluted in 10 mm maltose along with stoichiometrically bound V1ΔH. Elution fraction E1 (Fig. S3A) exhibited significant MgATPase activity (Fig. S3B), indicating that a stoichiometric complex of V1ΔH with MBP-H was capable of hydrolyzing MgATP.

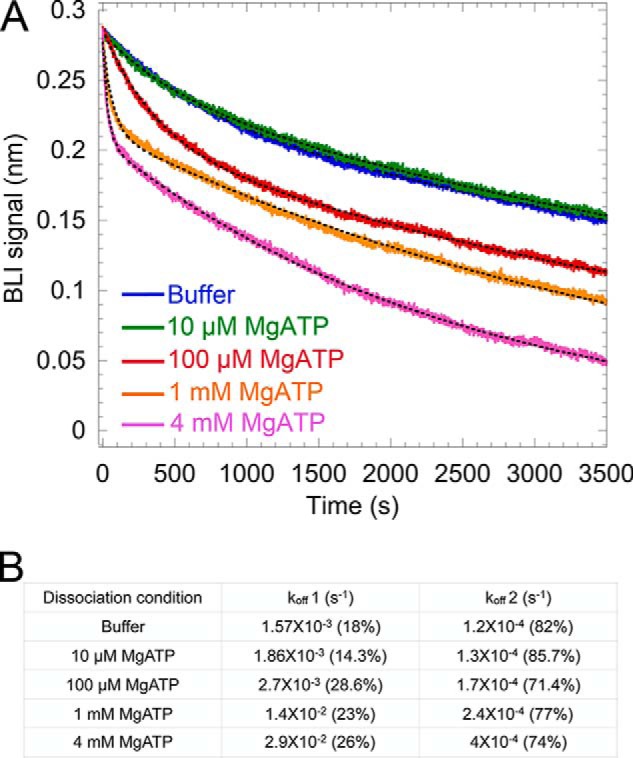

A consistent feature of the dissociation curve of V1ΔH from H in MgATP was its biphasic nature (Fig. 6A, orange trace), indicating that MgATP hydrolysis–dependent destabilization was transient. We found that, by using different concentrations of MgATP during dissociation, we were able to regulate the fast phase of the dissociation rate and consequently the duration of destabilization (Fig. 7). Not only does this experiment confirm MgATP hydrolysis as being the cause of V1–H destabilization, it also explains why the destabilization is transient. Using Pi release–based ATPase assays, it has been shown that MgATPase activity of V1ΔH subsides rapidly with time (25). This rapid decrease in activity, which is also observed in an ATP-regenerating assay (Fig. S4), has been attributed to the trapping of MgADP in a catalytic site, a phenomenon termed MgADP inhibition. We have observed that MgADP inhibition of V1ΔH is more efficient under high Mg2+ (and by extension high MgATP) concentrations and that decreasing the initial concentration of MgATP results in delayed MgADP inhibition (Fig. S4). In the BLI experiment shown in Fig. 7, decreasing the concentration of MgATP to 100 μm (Fig. 7, red trace) and consequently decreasing the rate of MgATP hydrolysis led to a delay in the culmination of the fast dissociation phase. Taken together, these data suggest that MgATP hydrolysis causes transient destabilization of the V1–H interaction until MgADP inhibition sets in.

Figure 7.

Modulation of the dissociation rate of V1ΔH from H by varying the concentration of MgATP. A, sensorgrams of V1ΔH dissociation from immobilized H subunit in the absence (blue) and presence of MgATP (10 μm, purple; 100 μm, red; 1 mm, orange; 4 mm, pink). A representative from two independent experiments is shown. B, off-rates determined by fitting the sensorgrams in A to dual-exponential equations.

Discussion

V-ATPase is regulated by reversible disassembly, a process that involves the breakage and reformation of several protein–protein interactions at the interface of V1 and Vo. These interactions are mediated by the central rotor of V1 (DF) binding to Vo's subunit d and the three peripheral stalks (EG1–3) that link the collar subunits H and C to aNT (see Fig. 2A). Both H and C are two domain proteins, and we previously found that Chead binds EG with high affinity, whereas Cfoot and EG bind aNT weakly. Here, we analyzed binding of H and HNT to isolated EG, aNT, and V1ΔH purified from yeast. We found that the majority of the binding energy between H and V1 is contributed by the interaction between HNT and EG and that binding of HNT to EG is much stronger when EG is part of V1 compared with isolated EG. However, only one copy of HNT binds V1ΔH with high affinity, indicating that the three EGs on V1 are in different conformations and that only one of these conformations (EG1) is competent for H binding. The three different conformations of the EGs are evident from the crystal structure of autoinhibited V1 (22) as well as the cryo-EM structures of V1Vo (20, 21). The observation that HNT binds only EG1 as part of V1 with high affinity suggests that HNT's preference is a result, and not the cause, of the conformational asymmetry of the peripheral stalks, which most likely originates in the catalytic core of V1 (A3B3DF). Although we were not able to detect an interaction between isolated HCT and V1ΔH, the observation that intact H binds V1ΔH with significantly higher affinity compared with HNT suggests that the contact between HCT and A3B3DF seen in the V1 crystal structure (22) contributes to the avidity of the V1–H interaction. In addition, much like the Cfoot–aNT–EG low-affinity (but high-avidity) ternary junction, we found that H and aNT interact weakly. Taken together, the data support and extend our earlier findings that V1 and Vo are held together by multiple weak interactions that allow rapid breaking and reforming in response to cellular needs.

MgATP hydrolysis–dependent destabilization of the V1–H interaction

Studies in yeast have shown that membrane-detached V1 has no measurable MgATPase activity, a property of WT V1 that has been attributed to the presence of the inhibitory H subunit (25). Therefore, our BLI data showing that the V1–H interaction is destabilized in the presence of MgATP came as a surprise as we did not expect V1(ΔH)H to be catalytically active. In contrast, previous biochemical studies had shown that V1ΔH retained ∼20% MgATPase activity upon addition of an excess of recombinant H, an observation that, at the time, was attributed to substoichiometric binding of H (39). However, using pulldown assays, we here show that a stoichiometric complex of V1ΔH with H has indeed transient MgATPase activity, indicating that WT V1 isolated from yeast is not equivalent to reconstituted V1(ΔH)H. One striking difference between V1 and V1(ΔH)H is that V1 contains ∼1.3 mol/mol of tightly bound ADP, whereas V1ΔH, and by extension V1(ΔH)H, has only ∼0.4 mol/mol of ADP (22). This suggests that V1's ATPase activity is inhibited by tightly bound ADP and that the lack of ADP in V1(ΔH)H allows transient MgATP hydrolysis with the associated conformational changes leading to destabilization of the V1–H interaction on the BLI sensor.

MgADP inhibition is a conserved feature of the catalytic headpiece of rotary ATPases wherein, under ATP-regenerating conditions, the rate of MgATP hydrolysis decreases due to retention of tightly bound MgADP at a closed catalytic site. The MgADP-inhibited state is a conformation off-pathway from the catalytic cycle and associated with a structural change in the catalytic site (43). MgADP inhibition has been observed in both the F1-ATPase (e.g. F1 from bovine heart (44)) and Bacillus PS3 (45)) and the cytosolic A1/V1 sector from Thermus thermophilus (46). Parra et al. (25) reported a decrease in MgATPase activity of purified yeast V1ΔH using Pi release assays, and we have observed a similar decrease in MgATPase activity of V1ΔH using an ATP-regenerating assay system (22) (Fig. S4).

Interplay of MgADP inhibition with the V1–H interaction

The structure of autoinhibited V1 revealed an inhibitory loop in HCT (amino acids 408–414) that mediates important contacts with V1. First, HCT binds to the C-terminal domain of subunit B, thereby stabilizing the corresponding catalytic A–B interface in its open conformation. Second, it interacts with two α-helical turns in the central rotor subunit D (residues 38–45) (22) (Fig. 2B). At any given rotational state of V1, only one of the catalytic sites is in the open state with the two α-helical turns from the central rotor facing the open site (22, 47). It is therefore evident that HCT preferentially binds to the open catalytic site with the central rotor in a particular conformation. Our data suggest that the peripheral stalks exhibit a conformational asymmetry, which most likely originates from the conformations of the catalytic core of the enzyme (A3B3DF). HNT preferentially interacts with EG1, the peripheral stalk associated with the open catalytic site. Under the conditions of our BLI experiments, when V1ΔH is bound to subunit H on the sensor, both HNT and HCT are associated with their binding partners at the open catalytic site, resulting in overall tight binding of H as evident from the observed slow dissociation of V1ΔH from the BLI sensor (Fig. 8A). When sensors containing V1ΔH bound to MBP-H are dipped into MgATP, the nucleotide binds to the open catalytic site and is hydrolyzed. Subsequent MgATP hydrolysis results in central stalk rotation, which destabilizes the interaction with HCT. The conformational changes are also propagated to the peripheral stalks, resulting in destabilization, and ultimately breaking, of the interaction between HNT and EG1 (Fig. 8B). However, MgATP hydrolysis on V1(ΔH)H is transient and stops once inhibitory MgADP gets trapped in a tight catalytic site. All the V1(ΔH)H complexes that withstood transient MgATP hydrolysis are now bound with high affinity because the binding site for HCT is restored once the MgADP-inhibited conformation is obtained (Fig. 8C). Therefore, we conclude that the lack of inhibitory MgADP in V1(ΔH)H allows transient MgATP hydrolysis and destabilization of the V1–H interaction and that high-affinity binding of H is restored once inhibitory MgADP is trapped in a catalytic site.

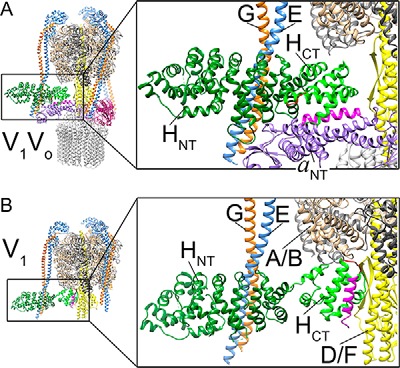

Figure 8.

Model for the effect of MgATP hydrolysis on the V1–subunit H interaction. Shown is a view of V1 from the membrane with H shown in green, peripheral stalk subunits EG in blue and orange, central rotor subunits DF in yellow, catalytic A subunit in tan, and B subunit in gray. V1ΔH binds subunit H with high affinity in the absence of nucleotide (A). However, when MgATP is added to the system, it binds to the empty catalytic sites of V1, leading to MgATP hydrolysis (B). Cooperative and cyclical MgATP hydrolysis in V1 leads to conformational changes in the three A/B pairs between open (O), loose (L), and tight (T) states. These cyclical switches of the A/B pairs are accompanied by structural changes in the associated EG heterodimers, which interchange between conformations denoted as EG1, EG2, and EG3. Because EG1 is the preferred binding site for HNT, a change in conformation of EG1 to EG3 causes a destabilization of the EG–HNT interaction. MgATP hydrolysis causes the counterclockwise rotation of the central rotor (DF) by ∼120°. Rotation of the central rotor along with conformational changes in the catalytic subunits causes destabilization of the V1–HCT interaction. As observed in the BLI experiments, only a subset of the V1–H interactions are destabilized upon MgATP hydrolysis. The catalytic cycle stops once MgADP is bound in a tight site, causing MgADP inhibition. The V1–H interactions that withstand MgATP hydrolysis subsequently remain bound with high affinity under ADP-inhibited conditions (C).

Considering the here observed MgATP hydrolysis–dependent destabilization of the interaction between H (and HNT) with V1 raises the question: how is this interaction maintained in V1Vo during rotational catalysis? Between the three rotational states of the enzyme observed by cryo-EM (21), minor conformational differences are observed for the peripheral stalk bound to H (EG1 in V1Vo). In V1Vo, besides providing binding sites for both HNT and HCT, aNT also interacts with and probably stabilizes the N termini of EG1 (Figs. 1A and 2A). The N-terminal region of the peripheral stalks have been described as unstable and flexible based on experiments conducted with isolated EG (33) and EG as part of A1/V1 (48) and as seen in the V1 crystal structure (22). With EG1's N termini unsupported, as in membrane-detached V1, expected conformational changes associated with rotary catalysis would be larger than those observed in V1Vo. Hence, although multiple interactions with aNT maintain the conformation of EG1 in V1Vo, the lack of these interactions in V1 enable rotary catalysis–driven conformational changes in EG1 with concomitant destabilization of the HNT–EG1 interaction.

Implications for the mechanism of reversible disassembly

Experiments conducted with yeast spheroplasts, isolated vacuoles, and purified V1Vo have established that efficient disassembly of V-ATPase requires a catalytically active complex (49–51). From a structural comparison with the three rotational states of V1Vo, we previously noted that upon disassembly of the holoenzyme autoinhibited V1 and Vo end up in different rotational states: V1 in state 2 and Vo in state 3 (22, 52, 53). This suggests that the MgATPase activity that is necessary for efficient disassembly serves to generate the rotational state mismatch associated with enzyme dissociation, a mismatch that likely functions to prevent rebinding of V1 to Vo under cellular conditions that favor the disassembled state. It is well established that enzyme dissociation is accompanied by a release of subunit C into the cytosol, and it is possible that the energy from ATP hydrolysis also serves to break the high-affinity EGChead interaction (33). Live cell imaging has captured V1 on vacuolar membranes while C is released into the cytosol upon glucose removal, suggesting that C release may be one of the initial steps of disassembly. Our data suggest that, due to catalysis-driven conformational changes in EG, membrane-detached V1 sector is incapable of binding H in a stable conformation while MgATP is being hydrolyzed at the catalytic sites. Therefore, it is possible that V1 detaches from Vo on vacuolar membranes after its MgATPase activity is completely silenced. The specificity of HNT and HCT for their binding sites on V1 supports a model wherein once V1 is MgADP-inhibited in rotational state 2 the proximity of the open catalytic site and central rotor favor HCT's conformational switch to its inhibitory position on V1. At the same time, by binding and stabilizing the open catalytic site, HCT facilitates the trapping of MgADP in the adjacent closed catalytic site (22). Hence, inhibitory MgADP and subunit H synergize by stabilizing each other to ensure that free V1 remains in the autoinhibited state to prevent wasteful ATP hydrolysis when V-ATPase's proton-pumping activity is down-regulated.

The autoinhibited state of V1 (with MgADP in a closed catalytic site stabilized by HCT bound to an open catalytic site) is likely a low-energy state of V1. For reassembly to occur, V1 needs to be “reactivated” to allow HCT to switch from its binding site on V1 to bind aNT in V1Vo. Based on our observations in this study, we speculate that release of inhibitory MgADP and subsequent MgATP binding/hydrolysis induce structural changes in V1 that detach HCT, making it available to bind aNT, in turn coupling V1 to Vo. What then causes the required release of inhibitory MgADP from cytosolic V1? Although this mechanism is currently not understood, it is possible that one of the protein factors that have been shown to be required for efficient reassembly, such as the regulator of the ATPase of vacuolar and endosomal membranes (RAVE) complex (54) or aldolase (55), plays a role in the release of inhibitory ADP, thereby allowing HCT to assume its binding site on aNT and restore MgATP hydrolysis–driven proton pumping.

Experimental procedures

Materials and methods

Plasmids encoding subunit H and its C-terminal domain (HCT; residues 352–478) N-terminally tagged with a Prescission protease-cleavable maltose-binding protein (MBP-H and MBP-HCT encoded by a pMalPPase vector derived from pMAL-c2E), a yeast strain deleted for subunits H and G (39), and a pRS315 vector containing FLAG-tagged subunit G (56) were kind gifts from Dr. Patricia Kane, SUNY Upstate Medical University.

Plasmid construction

The plasmid expressing the N-terminal domain of subunit H (HNT; residues 1–354) was made using the above MBP-H pMalPPase vector as a template for QuikChange mutagenesis to delete the nucleotide sequence coding for amino acids 355–478 using the following primers: HNT1–354 F, GGA AAT CCT AGA AAA CGA GTA CCA AGA ATT GAC CTA AAA GCT TGG CAC TGG CCG TCG TTT TAC AAC GTC G; HNT1–354 R, GAC GGC CAG TGC CAA GCT TTT AGG TCA ATT CTT GGT ACT CGT TTT CTA GGA TTT CCT TG. The construction of the pMalPPase plasmid encoding N-terminally MBP-tagged aNT(1–372) has been described (26).

Expression and purification of recombinant V-ATPase subunits

V-ATPase subunit constructs HNT, EG, HCT, H, and aNT were expressed in E. coli strain Rosetta2, grown to midlog phase in rich broth (LB Miller plus 0.2% glucose) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml). Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (except for expression of EG where 1 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was used). Expression was induced at 30 °C for 6 h for HNT, 20 °C for 6 h for H, 20 °C for ∼16 h for aNT, 25 °C for ∼16 h for HCT, and 30 °C for 6 h for EG. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in amylose column buffer (CB; 20 mm Tris-HCl, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.4), and stored at −20 °C until use. For purification, cells were treated with DNase (67 μg/ml), lysozyme (840 μg/ml), and PMSF (1 mm) before lysis by sonication. The lysate was then cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was diluted 1:4 with CB and applied to an amylose affinity column at a rate of 1 ml/min, and nonspecifically bound material was removed by washing with 12 column volumes of CB followed by 15 column volumes of CB without NaCl. Bound protein was eluted using 25 ml of 10 mm maltose in CB without salt. The MBP tag was cleaved using Prescission protease as described (34). H, HCT, and aNT were separated from MBP by anion exchange chromatography (Mono Q) using a linear gradient of 0–300 mm NaCl in 25 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7, for elution. Residual MBP was removed by a small amylose column, and the concentrated protein was subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex S75 column (1.6 × 50 cm) for H and HCT and a Superdex 200 column of the same size for aNT. HNT was separated from MBP using a gravity DEAE (anion exchange) column. At a pH of 6.5, MBP was immobilized on the DEAE column, and the HNT flowed through. The flow-through was collected, concentrated, and subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex S75 column (1.6 × 50 cm). EG heterodimer was purified as described (33).

Purification of V1ΔH

V1-ATPase lacking subunit H was purified as described (22). Briefly, the yeast strain deleted for the genes encoding subunits H and G was transformed with a pRS315 plasmid encoding subunit G with an N-terminal FLAG tag (56). The cells were grown in synthetic defined medium lacking Leu to an OD of ∼4.0 and harvested by centrifugation, and the cell pellets were resuspended in TBSE (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA) and stored at −80 °C until use. Thawed cells were supplemented with 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mm PMSF, and 2 μg/ml each of pepstatin and leupeptin before lysis by 15 passes through a microfluidizer with intermittent cooling on ice. The lysate was centrifuged at 4000 × g for 25 min, and the resultant supernatant was centrifuged again at 13,000 × g for 40 min. The cleared lysate was applied to a 5-ml FLAG column (Sigma) topped with Sephadex G50 and pre-equilibrated in TBSE. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of TBSE and eluted using 0.1 mg/ml FLAG peptide. V1ΔH-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated, and resolved using a Superdex 200 1.6 × 50-cm column attached to an ÄKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and concentrated to 10 mg/ml, and the activity of the complex was measured using a coupled enzyme assay as described below (22).

CD spectroscopy

CD spectra were recorded on an Aviv 202 spectropolarimeter using a 2-mm–path length cuvette. CD spectra were recorded between 250 and 195 nm in 25 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7, and protein stability was monitored by recording the CD signal at 222 nm as a function of temperature. For cysteine-containing proteins, 0.3–1 mm TCEP was included in the buffer. Protein concentrations of H, HNT, HCT, and aNT were 2, 2.25, 9.2, and 2.36 μm, respectively. The far-UV CD spectrum of 6.7 μm HNT–EG complex was obtained with protein dissolved in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm TCEP, pH 8 buffer at 4 °C followed by monitoring the temperature dependence of the CD signal at 222 nm.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The thermodynamic parameters of the interaction between HNT and EG and between HCT and aNT were determined using a Microcal VP-ITC isothermal titration calorimeter. The interaction of HNT and EG was monitored by titrating a stock of 0.278 mm HNT into 0.0315 mm EG in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm TCEP, pH 8, at 10 °C. A total of 30 injections with 5% saturation per injection was carried out. The average value of signal postsaturation (last eight titration points) was subtracted from the HNT into EG titration. Complex formation between aNT and H was analyzed by titrating 0.3 mm H into 0.017 mm aNT in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm TCEP, pH 8. A blank titration of H into buffer was subtracted from the aNT into H titration using the curve fit option in OriginLab. ITC data were analyzed using VP-ITC programs in OriginLab.

Biolayer interferometry

BLI was used to measure the association and dissociation kinetics of interaction between V1ΔH and MBP-tagged H, HNT, and HCT. An Octed-RED system and AMC–coated sensors (FortéBio, AMC biosensors, catalogue number 18-5088) were used to monitor protein–protein binding and dissociation for determination of binding affinities. Anti-MBP antibody (New England Biolabs) at 1 μg/ml was immobilized on the AMC biosensors. The anti-MBP antibody formed the bait for MBP-tagged H, HNT, and HCT (used at 5 μg/ml). Biosensors with immobilized H, HNT, or HCT were dipped in varying concentrations of V1ΔH followed by buffer to measure association and dissociation rates. BLI buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mg/ml BSA) was used in all BLI experiments to reduce nonspecific binding to the biosensors except for experiments in the presence of nucleotides where the EDTA concentration was reduced to 0.5 mm. All steps were done at 22 °C with each biosensor agitated in 0.2 ml of sample at 1000 rpm and a standard measurement rate of 5 s−1. Control experiments were performed to check for any nonspecific binding interaction between the antibodies and the proteins used. Reference sensors were used in each experiment with immobilized MBP-H/HNT/HCT but no V1ΔH. FortéBio data analysis software (version 6.4) was used for subtraction of reference sensors, Savitzky-Golay filtering, and global fitting of the kinetic rates of V1ΔH binding with H, HNT, or HCT.

ATPase activity assays

MgATPase activity of V1, V1ΔH, and V1(ΔH)H was measured using an ATP-regenerating assay as described (22). Briefly, 10 μg of the V1 mutant was added to an assay mixture containing 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATP, 30 units/ml each of lactate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase, 0.5 mm NADH, 2 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, at 37 °C. The decrease of absorbance at 340 nm was measured in the kinetics mode on a Varian Cary Bio100 spectrophotometer.

Native gel electrophoresis

For native gel electrophoresis, purified V-ATPase subunits and subcomplexes were resolved using 2% agarose gels in 20 mm bis-Tris-acetic acid, pH 6, 1 mm TCEP. Gels were resolved for 1 h at 100 V, fixed in 25% isopropanol, 10% acetic acid for 30 minutes, rinsed in 95% ethanol, and dried on a slab dryer for 2 h at 80 °C. The dried gel was stained with Coomassie G and destained in fixing solution.

Author contributions

S. S., R. A. O., and S. W. conceptualization; S. S. data curation; S. S. formal analysis; S. S. validation; S. S. investigation; S. S. visualization; S. S. and R. A. O. methodology; S. S. writing-original draft; S. S., R. A. O., and S. W. writing-review and editing; R. A. O. and S. W. supervision; S. W. funding acquisition; S. W. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Patricia Kane for reagents, Dr. Stewart Loh for assistance with CD data collection, and Dr. Thomas Duncan for assistance with BLI data collection and analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM058600 and a Bridge Grant from SUNY Upstate Medical University (to S. W.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4.

- V-ATPase

- vacuolar H+-ATPase

- V1

- ATPase sector of the vacuolar ATPase

- Vo

- membrane sector of the vacuolar ATPase

- aNT

- N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the a subunit

- BME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- BLI

- biolayer interferometry

- TCEP

- tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- AMC

- anti-mouse Fc capture

- AMPPNP

- 5′-adenylyl-β,γ-imidodiphosphate

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- CB

- column buffer

- bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

References

- 1. Forgac M. (2007) Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 917–929 10.1038/nrm2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frattini A., Orchard P. J., Sobacchi C., Giliani S., Abinun M., Mattsson J. P., Keeling D. J., Andersson A. K., Wallbrandt P., Zecca L., Notarangelo L. D., Vezzoni P., and Villa A. (2000) Defects in TCIRG1 subunit of the vacuolar proton pump are responsible for a subset of human autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Nat. Genet. 25, 343–346 10.1038/77131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thudium C. S., Jensen V. K., Karsdal M. A., and Henriksen K. (2012) Disruption of the V-ATPase functionality as a way to uncouple bone formation and resorption—a novel target for treatment of osteoporosis. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 13, 141–151 10.2174/138920312800493133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karet F. E., Finberg K. E., Nelson R. D., Nayir A., Mocan H., Sanjad S. A., Rodriguez-Soriano J., Santos F., Cremers C. W., Di Pietro A., Hoffbrand B. I., Winiarski J., Bakkaloglu A., Ozen S., Dusunsel R., et al. (1999) Mutations in the gene encoding B1 subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness. Nat. Genet. 21, 84–90 10.1038/5022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown D., Smith P. J., and Breton S. (1997) Role of V-ATPase-rich cells in acidification of the male reproductive tract. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williamson W. R., and Hiesinger P. R. (2010) On the role of v-ATPase V0a1-dependent degradation in Alzheimer disease. Commun. Integr. Biol. 3, 604–607 10.4161/cib.3.6.13364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun-Wada G. H., Toyomura T., Murata Y., Yamamoto A., Futai M., and Wada Y. (2006) The a3 isoform of V-ATPase regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4531–4540 10.1242/jcs.03234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu X., Yu H., Liu S. H., Brodsky F. M., and Peterlin B. M. (1998) Interactions between HIV1 Nef and vacuolar ATPase facilitate the internalization of CD4. Immunity 8, 647–656 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80569-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sennoune S. R., Bakunts K., Martínez G. M., Chua-Tuan J. L., Kebir Y., Attaya M. N., and Martínez-Zaguilán R. (2004) Vacuolar H+-ATPase in human breast cancer cells with distinct metastatic potential: distribution and functional activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C1443–C1452 10.1152/ajpcell.00407.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kane P. M. (2012) Targeting reversible disassembly as a mechanism of controlling V-ATPase activity. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 13, 117–123 10.2174/138920312800493142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fais S., De Milito A., You H., and Qin W. (2007) Targeting vacuolar H+-ATPases as a new strategy against cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 10627–10630 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkens S. (2005) Rotary molecular motors. Adv. Protein Chem. 71, 345–382 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)71009-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muench S. P., Trinick J., and Harrison M. A. (2011) Structural divergence of the rotary ATPases. Q. Rev. Biophys. 44, 311–356 10.1017/S0033583510000338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Futai M., Nakanishi-Matsui M., Okamoto H., Sekiya M., and Nakamoto R. K. (2012) Rotational catalysis in proton pumping ATPases: from E. coli F-ATPase to mammalian V-ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1711–1721 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kitagawa N., Mazon H., Heck A. J., and Wilkens S. (2008) Stoichiometry of the peripheral stalk subunits E and G of yeast V1-ATPase determined by mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3329–3337 10.1074/jbc.M707924200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Powell B., Graham L. A., and Stevens T. H. (2000) Molecular characterization of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase proton pore. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23654–23660 10.1074/jbc.M004440200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mazhab-Jafari M. T., Rohou A., Schmidt C., Bueler S. A., Benlekbir S., Robinson C. V., and Rubinstein J. L. (2016) Atomic model for the membrane-embedded VO motor of a eukaryotic V-ATPase. Nature 539, 118–122 10.1038/nature19828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilkens S., Inoue T., and Forgac M. (2004) Three-dimensional structure of the vacuolar ATPase. Localization of subunit H by difference imaging and chemical cross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41942–41949 10.1074/jbc.M407821200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Z., Zheng Y., Mazon H., Milgrom E., Kitagawa N., Kish-Trier E., Heck A. J., Kane P. M., and Wilkens S. (2008) Structure of the yeast vacuolar ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35983–35995 10.1074/jbc.M805345200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rawson S., Phillips C., Huss M., Tiburcy F., Wieczorek H., Trinick J., Harrison M. A., and Muench S. P. (2015) Structure of the vacuolar H+-ATPase rotary motor reveals new mechanistic insights. Structure 23, 461–471 10.1016/j.str.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao J., Benlekbir S., and Rubinstein J. L. (2015) Electron cryomicroscopy observation of rotational states in a eukaryotic V-ATPase. Nature 521, 241–245 10.1038/nature14365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oot R. A., Kane P. M., Berry E. A., and Wilkens S. (2016) Crystal structure of yeast V1-ATPase in the autoinhibited state. EMBO J. 35, 1694–1706 10.15252/embj.201593447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang J., Feng Y., and Forgac M. (1994) Proton conduction and bafilomycin binding by the V0 domain of the coated vesicle V-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23518–23523 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gräf R., Harvey W. R., and Wieczorek H. (1996) Purification and properties of a cytosolic V1-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20908–20913 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parra K. J., Keenan K. L., and Kane P. M. (2000) The H subunit (Vma13p) of the yeast V-ATPase inhibits the ATPase activity of cytosolic V1 complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21761–21767 10.1074/jbc.M002305200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Couoh-Cardel S., Milgrom E., and Wilkens S. (2015) Affinity purification and structural features of the yeast vacuolar ATPase Vo membrane sector. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 27959–27971 10.1074/jbc.M115.662494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kane P. M. (1995) Disassembly and reassembly of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17025–17032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sumner J. P., Dow J. A., Earley F. G., Klein U., Jäger D., and Wieczorek H. (1995) Regulation of plasma membrane V-ATPase activity by dissociation of peripheral subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5649–5653 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trombetta E. S., Ebersold M., Garrett W., Pypaert M., and Mellman I. (2003) Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science 299, 1400–1403 10.1126/science.1080106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sautin Y. Y., Lu M., Gaugler A., Zhang L., and Gluck S. L. (2005) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated effects of glucose on vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly, translocation, and acidification of intracellular compartments in renal epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 575–589 10.1128/MCB.25.2.575-589.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lafourcade C., Sobo K., Kieffer-Jaquinod S., Garin J., and van der Goot F. G. (2008) Regulation of the V-ATPase along the endocytic pathway occurs through reversible subunit association and membrane localization. PLoS One 3, e2758 10.1371/journal.pone.0002758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stransky L. A., and Forgac M. (2015) Amino acid availability modulates vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 27360–27369 10.1074/jbc.M115.659128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oot R. A., and Wilkens S. (2010) Domain characterization and interaction of the yeast vacuolar ATPase subunit C with the peripheral stator stalk subunits E and G. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24654–24664 10.1074/jbc.M110.136960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oot R. A., and Wilkens S. (2012) Subunit interactions at the V1-Vo interface in yeast vacuolar ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13396–13406 10.1074/jbc.M112.343962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Curtis K. K., Francis S. A., Oluwatosin Y., and Kane P. M. (2002) Mutational analysis of the subunit C (Vma5p) of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8979–8988 10.1074/jbc.M111708200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ho M. N., Hirata R., Umemoto N., Ohya Y., Takatsuki A., Stevens T. H., and Anraku Y. (1993) VMA13 encodes a 54-kDa vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit required for activity but not assembly of the enzyme complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18286–18292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu M., Tarsio M., Charsky C. M., and Kane P. M. (2005) Structural and functional separation of the N- and C-terminal domains of the yeast V-ATPase subunit H. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36978–36985 10.1074/jbc.M505296200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sagermann M., Stevens T. H., and Matthews B. W. (2001) Crystal structure of the regulatory subunit H of the V-type ATPase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7134–7139 10.1073/pnas.131192798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Diab H., Ohira M., Liu M., Cobb E., and Kane P. M. (2009) Subunit interactions and requirements for inhibition of the yeast V1-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13316–13325 10.1074/jbc.M900475200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu M., Vergara S., Zhang L., Holliday L. S., Aris J., and Gluck S. L. (2002) The amino-terminal domain of the E subunit of vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) interacts with the H subunit and is required for V-ATPase function. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38409–38415 10.1074/jbc.M203521200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Isaka Y., Ekimoto T., Kokabu Y., Yamato I., Murata T., and Ikeguchi M. (2017) Rotation mechanism of molecular motor V1-ATPase studied by multiscale molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys. J. 112, 911–920 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu Q., Leng X. H., Newman P. R., Vasilyeva E., Kane P. M., and Forgac M. (1997) Site-directed mutagenesis of the yeast V-ATPase A subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11750–11756 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kishikawa J., Nakanishi A., Furuike S., Tamakoshi M., and Yokoyama K. (2014) Molecular basis of ADP inhibition of vacuolar (V)-type ATPase/synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 403–412 10.1074/jbc.M113.523498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vasilyeva E. A., Minkov I. B., Fitin A. F., and Vinogradov A. D. (1982) Kinetic mechanism of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase. Inhibition by azide and activation by sulphite. Biochem. J. 202, 15–23 10.1042/bj2020015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jault J. M., Dou C., Grodsky N. B., Matsui T., Yoshida M., and Allison W. S. (1996) The α3β3γ subcomplex of the F1-ATPase from the thermophilic Bacillus PS3 with the βT165S substitution does not entrap inhibitory MgADP in a catalytic site during turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28818–28824 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakano M., Imamura H., Toei M., Tamakoshi M., Yoshida M., and Yokoyama K. (2008) ATP hydrolysis and synthesis of a rotary motor V-ATPase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20789–20796 10.1074/jbc.M801276200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arai S., Saijo S., Suzuki K., Mizutani K., Kakinuma Y., Ishizuka-Katsura Y., Ohsawa N., Terada T., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S., Iwata S., Yamato I., and Murata T. (2013) Rotation mechanism of Enterococcus hirae V1-ATPase based on asymmetric crystal structures. Nature 493, 703–707 10.1038/nature11778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou M., Politis A., Davies R., Liko I., Wu K. J., Stewart A. G., Stock D., and Robinson C. V. (2014) Ion mobility-mass spectrometry of a rotary ATPase reveals ATP-induced reduction in conformational flexibility. Nat. Chem. 6, 208–215 10.1038/nchem.1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Parra K. J., and Kane P. M. (1998) Reversible association between the V1 and V0 domains of yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase is an unconventional glucose-induced effect. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 7064–7074 10.1128/MCB.18.12.7064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. MacLeod K. J., Vasilyeva E., Merdek K., Vogel P. D., and Forgac M. (1999) Photoaffinity labeling of wild-type and mutant forms of the yeast V-ATPase A subunit by 2-azido-[32P]ADP. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32869–32874 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sharma S., and Wilkens S. (2017) Biolayer interferometry of lipid nanodisc-reconstituted yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Protein Sci. 26, 1070–1079 10.1002/pro.3143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stam N. J., and Wilkens S. (2017) Structure of the lipid nanodisc-reconstituted vacuolar ATPase proton channel: definition of the interaction of rotor and stator and implications for enzyme regulation by reversible dissociation. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 1749–1761 10.1074/jbc.M116.766790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oot R. A., Couoh-Cardel S., Sharma S., Stam N. J., and Wilkens S. (2017) Breaking up and making up: the secret life of the vacuolar H+-ATPase. Protein Sci. 26, 896–909 10.1002/pro.3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smardon A. M., Tarsio M., and Kane P. M. (2002) The RAVE complex is essential for stable assembly of the yeast V-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13831–13839 10.1074/jbc.M200682200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu M., Ammar D., Ives H., Albrecht F., and Gluck S. L. (2007) Physical interaction between aldolase and vacuolar H+-ATPase is essential for the assembly and activity of the proton pump. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24495–24503 10.1074/jbc.M702598200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Z., Charsky C., Kane P. M., and Wilkens S. (2003) Yeast V1-ATPase: affinity purification and structural features by electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47299–47306 10.1074/jbc.M309445200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.