Abstract

In mice, fetal/neonatal B-1 cell development generates murine CD5+ B cells (B1a) with autoreactivity. We analyzed B1a cells at the neonatal stage in a VH11/D/JH knock-in mouse line (VH11t) that generates an autoreactive antiphosphatidylcholine BCR. Our study revealed that antiphosphatidylcholine B1a cells develop in liver, mature in spleen, and distribute in intestine/colon, mesenteric lymph node (mLN), and body cavity as the outcome of B-1 cell development before B-2 cell development. Throughout life, self-renewing B-1 B1a cells circulate through intestine, mesenteric vessel, and blood. The body cavity–deposited B1a cells also remigrate. In old age, some B1a cells proceed to monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis. When neonatal B-1 B1a cells express an antithymocyte/Thy-1 autoreactivity (ATA) BCR transgene in the C.B17 mouse background, ATA B cells increase in PBL and strongly develop lymphomas in aging mice that feature splenomegaly and mLN hyperplasia with heightened expression of CD11b, IL-10, and activated Stat3. At the adult stage, ATA B cells were normally present in the mantle zone area, including in intestine. Furthermore, frequent association with mLN hyperplasia suggests the influence by intestinal microenvironment on lymphoma development. When cyclin D1 was overexpressed by the Eμ-cyclin D1 transgene, ATA B cells progressed to further diffused lymphoma in aged mice, including in various lymph nodes with accumulation of IgMhiIgDloCD5+CD23−CD43+ cells, resembling aggressive human mantle cell lymphoma. Thus, our findings reveal that early generated B cells, as an outcome of B-1 cell development, can progress to become lymphocytosis, lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma–like neoplasia in aged mice.

Introduction

Fetal/neonatal B-1 cell development in mice is derived from a Lin28b+Let7− B lineage precursor, with ability to generate autoreactive murine CD5+ B cells (B1a). In contrast, a Lin28b−Let-7+ B lineage precursor becomes predominate in adult B-2 cell development, and mature Bla generation declines (1, 2). In humans, Lin28b+Let7− cells also predominate at the fetal hematopoietic stage as compared with adult (1), resulting in a large proportion of CD5+ B cells in fetal lymphoid tissues and in cord blood (3, 4), whereas CD5+ B cells decline in postnatal development. In aging, CD5+ B cells neoplasms occur in humans. Both chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, show increased incidence with advancing age and express CD5+, with involvement of CD5+ B cells having unmutated BCRs, including stereotyped BCRs with autoreactivity. In mice, the early generated B-1–derived B1a cells self-renew throughout life (5), and high expression of T cell leukemia 1 (TCL1) oncogene in B1a cells by transgene (Tg) promoted generation of B-1–derived leukemia/lymphoma in aging, resembling human TCL1+ CLL. This early B-1 B1a cell origin was confirmed by the adoptive transfer of B1a cells present in young mice, including d10 neonatal spleen B1a cells (6). In these B-1–derived B cell leukemia/lymphoma, chromosome loss, syntenic to the 13q14 loss found in human CLL and MCL, also occurred (7). These results suggested that a portion of aged human CD5+ leukemia/lymphoma may be derived from early generated B cells as found in mice.

In humans, MCL is a rare and aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma as compared with CLL (8–10). Whether mouse B-1 development also generates human MCL-like neoplasia is currently undefined. MCL exhibits a higher frequency of unmutated BCR and higher IgM expression level than CLL and is mostly IgDlo, CD23−, and CD43+. Thus, the phenotype of IgMhi+IgDloCD5+CD23−CD43+, together with B220lo by altered CD45 glycosylation (10–12), resembles mouse B-1–derived B1a cells. A clear distinction between human MCL and CLL is the upregulation of cyclin D1 in MCL, mostly as an outcome of cyclin D1 translocation into the IgH locus, t(11;14) (q13;q32) (8, 10). Because Let7 microRNA targets cyclin D1 and the Lin28–Let7 axis controls cyclin D1 expression (13, 14), one possible consideration is that cyclin D1 translocation into IgH occurred often from the early generated Lin28+Let7− B lineage. These prompted a hypothesis that mouse B-1–derived B1a cells may also be able to generate MCL-like neoplasia when cyclin D1 is overexpressed. However, it has been known that cyclin D1 overexpression by Tg in mice is insufficient to detect B cell lymphoma generation, except the case of addition of mitogenic stimulus in aged mice (15), or together with cMyc Tg or proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein Bim deficiency (16, 17). Because early generated mouse B-1 B1a cells are known to continue to express moderately upregulated cMyc and downregulated Bmf as another proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein (6), infrequent B cells with certain restricted BCRs in B1a cells may have the capacity to become MCL-like neoplasia when cyclin D1 is overexpressed.

MCL exhibits as a diffuse pattern of lymphoid neoplasia throughout the body or at least involvement of a focal nodular component (8–10). A diffuse distribution pattern, often including enlarged spleen, was found by most MCLs and with lower survival. Although gastrointestinal (GI) tract involvement was originally reported as 13–30% in MCL, it appears that MCLs almost invariably involve the GI tract (18). Because mouse B-1–derived B1a cell distribution in intestine has been less well understood, we first analyzed the VH11/D/JH1 knock-in mouse line (VH11t) (19) to confirm the normal presence of B1a cells in intestine from neonatal to old age. This VH11t strain generates B1a cells predominantly with stereotyped VH11/Vk9(br9) BCR, a common autoreactive antiphosphatidylcholine (aPtC) BCR with reactivity to the damaged erythrocyte and with cross-reactivity, including with Escherichia coli bacteria (20, 21). In normal mice, VH11+aPtC B1a cells play a positive role in innate immunity (22) and are found in various mouse strains. VH11+aPtC B1a cell generation is restricted to the B-1 developmental outcome because VH11μ IgH does not associate with surrogate L chain; it is therefore unable to drive preBCR clonal expansion in B-2 development (23). To assess MCL-like neoplasia generation with potential intestinal involvement, we next analyzed antithymocyte/Thy-1 autoreactive (ATA) B cell Tg strains. Generation of mature B1a cells expressing the ATA BCR is also restricted to B-1 development, and increased expression of this ATA BCR by B1a cells led to spontaneous generation of lymphoma in aged mice on the C.B17 (BALB/c.Igh-1b) background (6, 24, 25). Studies of these VH11t and ATA Tg mice and further analysis of ATA Tg mice coexpressed with Eμ-cyclin D1 Tg revealed the normal presence of B1a cells in mantle zone areas of the intestine, splenomegaly, and mesenteric lymph node (mLN) hyperplasia generation by ATA B cells in aged mice, and cyclin D1 overexpression by ATA B cells leads to a further diffused pattern of lymphoid neoplasia generation, resembling MCL. In normal mice, B1a cells expressing CD11b (together with CD18 and αMβ2, as Mac-1) are restricted to the body cavity (26), and CD11b+ B1a cells are able to migrate into spleen/intestine/mLN tissues (27–30). CD11b is subsequently downregulated within the tissue environment after migration (31, 32). When TLR signal occurs, B1a cells migrate into tissues and produce IL-10 and then become normally autoregulated, controlling their expansion (28, 33). In contrast, CD11b expression with IL-10–pStat3 was common in both spontaneous and cyclin D1 Tg+ ATA B lymphomas. It is known that CD11b/CD18 Mac-1 promotes adhesion and migration (34, 35) and IL-10–pStat3 allows self-sustaining growth (36–38). Increased expression of cyclin D1, which can dysregulate cell cycle and enhance DNA repair (39), may have further promoted maintenance of CD11b+ and IL-10–pStat3+ B1a cells, more so than spontaneous lymphoma, to generate the diffuse pattern of MCL-like neoplasia in mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice

VH11t, transgenic mouse lines VH3609μ (ATAμTg), VH3609/Vk21-5 μκ (ATAμκTg; “3369”), and Eμ-hTCL1 Tg, and Thy-1 knockout (Thy-1KO) and CD40−/− mouse lines were all on the C.B17 mouse background, as previously described (6, 19, 24, 40). C.B17 mice were used as wild type (WT). Eμ-cyclin D1 (Bcl-1) Tg mice on C57BL/6 background were originally provided by Dr. J. Adams (16). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with a protocol (no. 00-10 and no. 87-17) approved by the Fox Chase Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry analysis and reagents

Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson). Multicolor flow cytometry analysis, sorting, and mAb reagents were described previously, including anti-VH11 idiotype Ab (P18-3H7), anti-Vk9 idiotype Ab (P18-13B5), and anti-ATA VH3609/Vk21-5 idiotype (ATAid) Ab (P9-19A4) (19, 40). Rat anti-VH11/Vk9 idiotype Ab (P18-7H11) IgG was made along with the anti-VH11id and anti-Vk9id Abs. PE-CD11b was M1/70. For intestinal tissue flow cytometry analysis, Peyer patch (PP) and neonatal d1-d10 tissues were prepared by the same standard procedure as with adult nonintestinal tissues.

For d10 colon, first centrifugation was at 1800 rpm for 10 min in small tubes containing 1 ml each and then pellets were resuspended and mixed as one mouse sample. Liver and spleen cell analysis was done by each individual mouse, and PP, colon, mLN, and peritoneal cavity (PerC) analysis were done using a mixture of two to four pooled mice.

B1a cell stimulation in vitro

FACS-purified B1a cells from VH11t spleen were cultured in 96-well U-plates at 2 × 105 cells in 150 μl medium per well, with or without stimulation. Stimulating reagents were as follows: anti-IgM (The Jackson Laboratory) at 10 μg/ml, anti-CD40 (eBioscience) at 5 μg/ml, LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) at 20 μg/ml, CpG (InvivoGen) at 3 μg/ml, and IL-10 (R&D Systems) at 0.01 μg/ml. For 6-mo spleen B cell stimulation, follicular B cells (FO B cells) (AA4−CD21+CD23+CD5−) from WT mice and mature ATA B cells (ATAid+ AA4−CD21−CD23−) expressing slightly increased CD11b were sorted from spleen and cultured with or without CpG for 24 h.

Intestinal tissue cryosection immunofluorescence analysis

Dissected intestine was gently flushed of stool material with ice-cold PBS in a 1-ml syringe and then frozen. Staining of ethanol-fixed frozen sections and microscope imaging were done as described previously (19). To visualize intestine area, isolectin B4 (BSI-B4; Sigma-Aldrich) and wheat germ agglutinin (Invitrogen) were used together with antilymphocyte Abs.

B cell lymphoma analysis

PBL analyses were performed every 3–4 mo for each mouse (6). A predominance of VH11+ aPtC or ATA B cells in total B cells without increased PBL was defined as monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL). In ATA Tg mice, after ATA B cell increase in PBL, splenomegaly was often noticed. At necropsy, tissues were analyzed, together with sorting of ATA B cells by flow cytometry, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), and Western blot analysis. In addition, histologic diagnoses were made using sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues stained with H&E.

qRT-PCR and RT-PCR assay

Gene expression was quantitated by real-time PCR, using TaqMan assays from Applied Biosystems, an ABI 7500 real-time thermal cycler, and ABI software (Life Technologies). Relative gene expression levels were normalized using β-actin (and sno202 for microRNA) values as a standard. Primer sets for RT-PCR were as follows: IL-10, 5′-GACTGGCATGAGGATCAGCA-3′ and 5′-GGCCTTGTAGACACCTTGGT-3′; and cyclin D1, 5′-AGGCAGCGCGCGTCAGCAGCC-3′ and 5′-TCCATGGCCCGGCCGTCTGGG-3′.

Western blotting

WT FO B cells and CD11b+ATA B lymphoma cells were purified by cell sorting (2 × 106 cells/tube), and cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–IL-10 (R&D Systems), anti–Tyr705pStat3 (Abcam), anti-Stat 3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti–β actin (Bethyl Laboratories).

Results

B-1–derived B1a cells are present in tissues (including intestine from neonatal to old age), circulate, and can become MBL

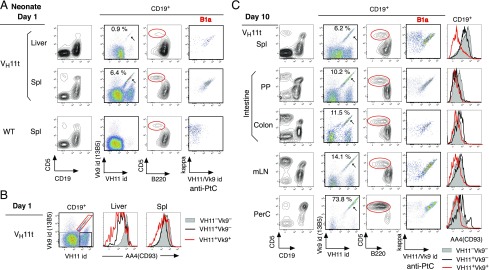

To assess the tissue distribution of B-1–derived B cells from birth to old age, VH11t was analyzed. One day after birth, B1a were detected in the liver, where B-1 development occurs, and also in spleen (Fig. 1A). Both of these B1a populations in VH11t mice were dominantly aPtC BCR B cells at the immature (AA4/CD93+) stage (Fig. 1B). At day 10, most aPtC B1a cells in spleen became mature (Fig. 1C). Mature aPtC B1a cells were also distributed in intestine, including in PP, colon, and mLN and became the dominant mature B cell population among PerC (Fig. 1C). Thus, B-1–derived B1a cells develop and distribute in neonatal stage, including in intestine, before B-2 development occurs.

FIGURE 1.

Presence of B1a cells in neonatal tissues, including in the intestine. (A) Day 1 VH11t liver and spleen cell analysis compared with WT mouse spleen. All showed presence of CD5+ CD19+ B cells, predominantly B220lo (red) as B1a cells. Percentage of anti-PtC B cells (VH11id+ Vk9id+) within VH11t CD19+ B cells is marked, and the presence of anti-PtC B cells within the B1a cells was shown by VH11/Vk9id+ and Igκ+ staining. (B) AA4 (AA4.1)/CD93 levels in day 1 VH11t liver and spleen B cells. Three B cell fractions in spleen (VH11id versus Vk9id) are marked, and data were compared with day 10 (C). (C) Day 10 VH11t tissue analysis, including PP, colon, and PerC. Data are representative of three experiments with VH11t.C.B17 mice. VH11t.C57BL/6 neonates (d1-10) also showed similar presence of aPtC B1a cells. id, idiotype.

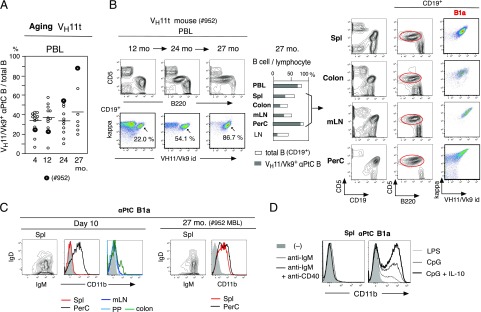

In 2-mo adult, B-2–derived non-aPtC B cells became the dominant B cells in various tissues. However, early generated B-1–derived aPtC B cells continued to be present in tissues, including in intestine, and were the dominant B cells in PerC (Supplemental Fig. 1). In old age, few mice showed dramatically increased aPtC B1a cells in PBLs as MBL, as exemplified by mouse no. 952 (Fig. 2A, 2B). In older age (27 mo) of this MBL mouse, aPtC B1a cells were also present in tissues, including in colon and mLN, and were the dominant presence in PerC, resembling neonates (Fig. 2B, right). In normal mice, B1a cells circulate (41), and these neonate- to old-aged aPtC B1a cell distribution data suggest that the major continued circulation of self-renewing B1a cells has been occurring through intestine, mesenteric lymphatic vessel, and thoracic duct with reentry to the blood circulation. A distinct surface phenotype of B1a cells in this MBL mouse spleen was the expression of CD11b (Fig. 2C, right). On day 10 neonatal stage, CD11b+ B1a cells were restricted to the body cavity, such as in PerC (Fig. 2C, left) as found in normal mouse adults (26). The induction of CD11b occurred in adult splenic CD11b− aPtC B1a cells by signaling through TLR, such as TLR4 (LPS) and TLR9 (CpG), with further CD11b increase induced by addition of IL-10 but not by BCR signaling (Fig. 2D). Thus, TLR signal involvement and altered B1a cell maintenance with an environment sensitivity deregulation in aging were considered as contributing factors to increase B1a cells.

FIGURE 2.

B1a cells expressing CD11b in the spleen of aged mice with MBL. (A) Frequency of VH11/Vk9+ aPtC B cells within PBL B cells in VH11t mice during aging, from 4 (original 13 mice) to 27 mo (seven mice). Filled circles are from the mouse that exhibited increased frequency with age (no. 952). (B) Characterization of no. 952 VH11t mouse. Left, PBL from 12 to 27 mo. Middle, At 27 mo, total B cell and VH11t+ aPtC B cell frequencies in lymphocytes in PBL and tissues. Right, Selected tissue analysis at 27 mo. (C) Comparison of CD11b expression level by aPtC B1a cells between day 10 neonate and 27 mo (no. 952) VH11t mice. CD5− B cells in adult spleen as a CD11b negative control (gray). B1a cells in spleen were both IgM+IgDlo/−. (D) Three days after indicated stimulation of spleen B1a cells from an adult (2 mo) VH11t mouse. Data are representative of two experiments.

B-1–derived ATA B cells are present in mantle zone areas and become lymphoma/leukemia in aged mice

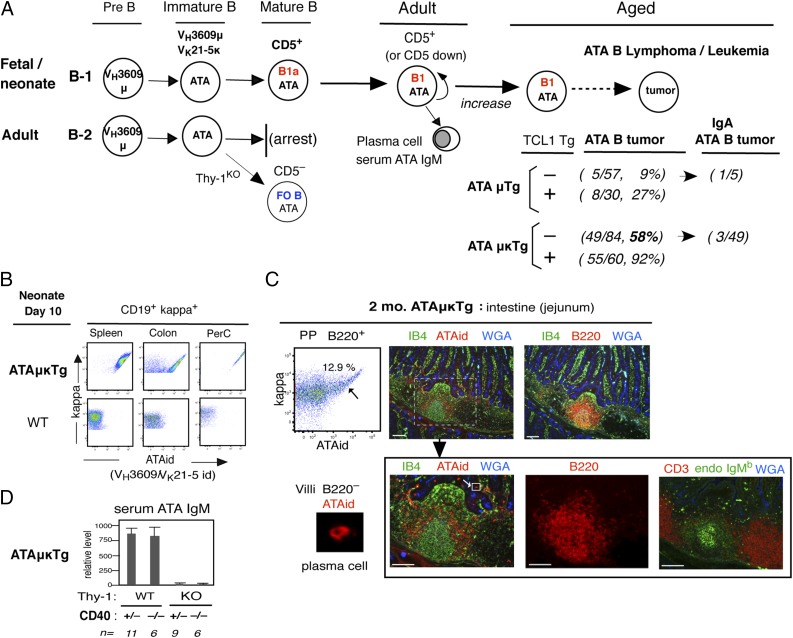

Most animals do not develop spontaneous B cell lymphoma, although lymphocytosis (MBL) can occur as found in VH11t mice. Thus, we proceeded to examine ATA B cell transgenic mouse lines. As shown previously and summarized in Fig. 3A, the VH3609μ/Vk21-5κ ATA BCR recognizes a specific Thy-1(CD90) glycoform predominantly expressed on immature thymocytes and in soluble form in serum (25, 42). These autoreactive ATA B cells are generated from fetal/neonatal B-1 development as CD5+ B1a cells through BCR signal and persist in adults, contributing to production of serum ATA IgM (24, 40). As shown in Fig. 3A, ATAμTg mice showed low incidence of ATA B lymphoma generation in aged mice. When all newly generated immature B cells were induced to express the ATA BCR from ATAμκTg with both IgH/IgL Tgs, a high incidence of spontaneous ATA B cell lymphoma occurred in aged (>12 mo) mice on a C.B17 background (6). The majority were ATA IgM lymphoma, and some switched to IgA with hyperplastic mLN together with splenomegaly (Supplemental Fig. 2). Coexpression with an Eμ-hTCL1 Tg resulted in the increased development of CLL-like leukemia (Fig. 3A) and often with splenomegaly as previously reported (6). In contrast to this B-1 developmental outcome, ATA B cell maturation does not occur through adult B-2 development, being arrested at the immature stage as a negative outcome (40), and the arrested B cells with TCL1 Tg+ did not show strong generation of ATA B leukemia/lymphoma (6). In Thy-1KO mice, B-2 development generates mature ATA B cells as CD5− FO B cells, with a very low incidence of ATA B tumor development with or without TCL1 Tg (6). Thus, ATA B lymphomas were dominantly from B-1 origin.

FIGURE 3.

ATA B cells localize in the mantle zone area of intestine and develop ATA B lymphoma/leukemia in aged mice. (A) Summary of autoreactive ATA B cell generation from fetal/neonatal B-1 development, self-renewal, natural serum ATA IgM production, and ATA B lymphoma/leukemia incidence in aged mice in the absence (spontaneous) or presence of TCL1 Tg in ATAμTg and ATAμκTg mice on the C.B17 background. Incidence of IgM switched to IgA as lymphoma in spontaneous ATA tumors is also listed. Adult B-2 development does not allow mature autoreactive ATA B cell generation by negative selection. Absence of self–Thy-1 Ag (ThyKO) allows ATA B cell maturation to generate CD5− FO B cells. (B) ATA B cell analysis (ATAid+) of day 10 ATAμκTg mouse B cells (CD19+κ+) in spleen, colon, and PerC in comparison with day 10 WT mouse B cells. (C) Two-mo ATAμκTg mouse jejunum. Left, Percentage of ATA B cells in PP B220+ B cells (also AA4−). Right (top), Presence of B220+ and B220−ATAid+ cells. Right (bottom), Black arrow shows the same enlarged PP area to compare the presence of ATA B cells, B220+ B cells, T cells, and endogenous IgM B cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. The panel at bottom left is an enlarged view of the marked box in villi (white arrow), which shows a B220−ATAid+ plasma cell. (D) Relative serum IgM level of ATAμκTg mice under normal (Thy-1WT) versus Thy-1KO background conditions, crossed with CD40 knockout mice (mean ± SE). IB4, BSI-B4, isolectin B4; WGA, wheat germ agglutinin.

In ATAμκTg mice before lymphoma generation, ATA B cells were broadly distributed in tissues in neonatal (10 d) stage, including in colon and PerC (Fig. 3B) as in VH11t mice. In adults, self-renewing mature ATAid+ cells continued to be present in tissues, including in intestine, and dominantly produce ATA B Abs. In small intestine, both B220+ ATA B cells and B220− (and CD19−) ATA plasma cells were present (Fig. 3C). ATA plasma cells were mostly in villi area. In PP, B220+ B cells in germinal center were predominantly non-ATA endogenous IgMb cells (Fig. 3C, bottom), whereas B220+ ATA B cells (presence confirmed by flow cytometry analysis in Fig. 3C upper left, together with AA4− as mature B cells) were found in mantle zones. Serum ATA IgM production in ATAμκTg mice in contrast to the same mice on a Thy-1KO background (40) was independent of CD40 signaling, not requiring contact with mature T cell CD40L to generate germinal center (Fig. 3D). In VH11t intestine, the aPtC B1a cells were also clearly located in the mantle zone area in PP (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Thus, analyses of intestine PP lymphoid follicles with a germinal center confirmed that B-1–derived B1a cells are present in the mantle zone area.

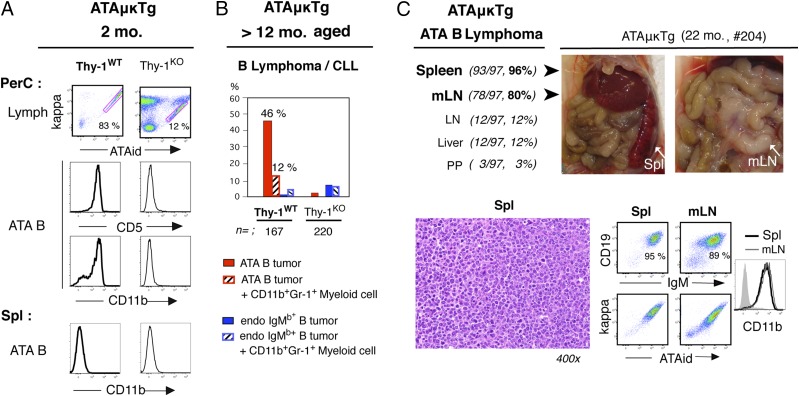

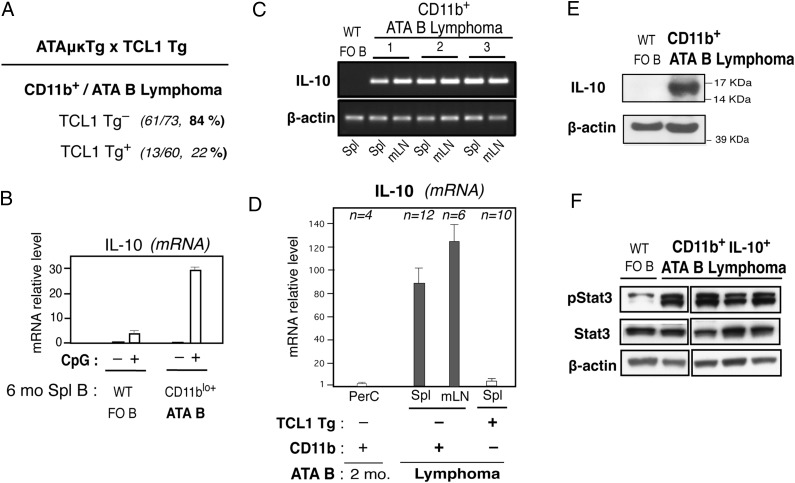

CD11b+ IL-10+ pStat3+ ATA B lymphoma

On the adult nontumor stage, CD5+ ATA B1a cells deposited in PerC in ATAμκTg mice were predominantly CD11b+, whereas ATA B cells in spleen were CD11b− (Fig. 4A, left), as normally found in WT and aPtC B1a cells. The presence of these CD5+CD11b+ B1a cells in PerC was a B-1 development outcome because ATA B cells present in PerC under Thy-1KO condition (FO B cells through B-2 development) were few, and these were CD5−CD11b− (Fig. 4A, right). In aging, the increased presence of ATA B cells in tissues occurred. ATA B cells in ATAμκTg mice increased in frequency in PBL with age (6), followed by high incidence of ATA B cell tumor generation by >12 mo of age (58%) (Fig. 4B), sometimes accompanied by increased CD11b+Gr-1+ immature myeloid cells. These ATA B lymphomas were associated with splenomegaly and often also exhibited enlargement of mLN (Fig. 4C), and expression of CD11b was frequent on these ATA B cells in both spleen and mLN (Figs. 4C, 5A). ATA B lymphomas were mostly IgM+ of small/medium size (Fig. 4C) as found in the majority of human CLL and MCL tumors (10). At 6 mo of age before tumor stage, slightly increased CD11b-expressing mature ATA B cells were detected in spleen and showed strong IL-10 mRNA increase after 24 h stimulation by CpG (Fig. 5B). In old age, spontaneously developed CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma cells expressed substantially higher levels of IL-10 mRNA in both spleen and mLN (Fig. 5C, 5D) than nonstimulated CD11b+ ATA B cells normally present in the PerC of 2-mo adults (Fig. 5D). Increased IL-10 mRNA+ ATA lymphomas also expressed IL-10 protein (Fig. 5E), and CD11b+IL-10+ ATA B lymphomas also expressed significant levels of activated Stat3 (Fig. 5F). In contrast to these spontaneously occurring ATA B tumor cells, when TCL1 Tg was expressed in ATA B cells, PBL leukemia generation became dominant together with strong splenomegaly (6) but without increased mLN involvement. Most of these TCL1 Tg+ ATA B lymphoma cells in spleen were CD11b− (Fig. 5A), and CD11b− TCL1 Tg+ ATA B tumor cells in spleen did not exhibit increased levels of IL-10 mRNA (Fig. 5D). In summary, ATA B lymphomas that spontaneously developed in old mice with mLN involvement featured CD11b expression, increased IL-10, and activated Stat3.

FIGURE 4.

CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma with splenomegaly and enlarged mLNs in aged ATAμκTg mice. (A) Two-mo ATAμκTg mice under normal (Thy-1WT) versus Thy-1KO conditions. PerC, ATA B (red bar with percentage in lymphocyte area) for CD5 and CD11b analysis. Spl, ATA B cell analysis for CD11b. In Thy-1WT, both arrested CD5+ATA B cells (T2) and mature B1a cells (CD5+AA4−CD21−CD23−, shown) were CD11b−. (B) Percentage of B lymphoma/leukemia that developed in ATAμκTg mice (>12 mo of age) under Thy-1WT versus Thy-1KO conditions. Incidence of >20% CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells copresent with ATA B cells in splenomegaly is listed separately. (C) Percentage of increased tissues with ATA B cells in ATAμκTg ATA B lymphoma and the data from one representative case (22-mo ATAμκTg mouse, no. 204); H&E staining of spleen section and flow cytometry of total spleen and mLN. spl, spleen.

FIGURE 5.

Spontaneous ATA B lymphoma expressing CD11b+, IL-10+, and pStat3+. (A) Frequency of CD11b+ ATA B cells in ATA B cell splenomegaly in ATAμκTg mice with or without TCL1 Tg (both C.B17 background). (B) IL-10 qRT-PCR. Twenty-four hours after with or without CpG stimulation of 6-mo adult WT FO B and ATA B cells in spleen. Slightly increased CD11b expression before stimulation by mature ATA B cells in spleen by flow cytometry analysis (n = 3 each, mean ± SE). (C) IL-10 RT-PCR. Three ATAμκTg mice with CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma in spleen and mLN. Two-month WT mouse splenic FO B cells as a control. (D) IL-10 qRT-PCR by ATA B cells in ATAμκTg mice with or without lymphoma (mean ± SE). Two-month nontumor CD11b+ATA B in PerC, aged mouse CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma in spleen and mLN, and CD11b− TCL1 Tg+ATA B lymphoma in spleen. High and low IL-10 mRNAs from these ATAμκTg mouse ATA B cells were all detectable by qRT-PCR (mean ± SE), and 2-mo PerC ATA B cells were used as a control (= 1.0). In contrast, expression of IL-10 was undetectable by WT FO B cells. (E) Western blot of IL-10 protein in CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma with increased IL-10 mRNA in comparison with WT FO B cells. (F) Western blot of four CD11b+IL-10+ ATA B lymphoma in ATAμκTg mice in comparison with WT FO B cells. pStat3, Tyrosin705 phosphorylated Stat3.

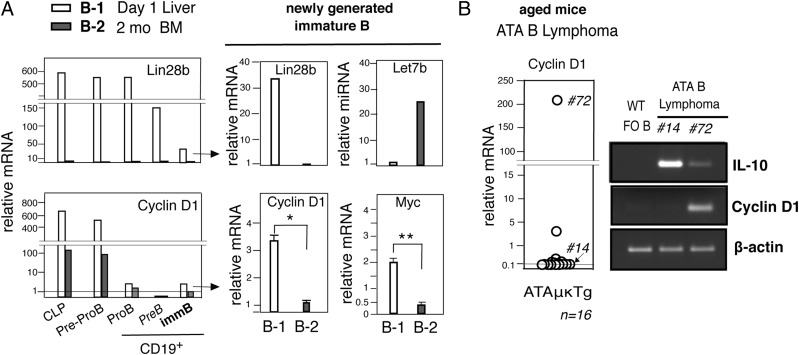

Occurrence of cyclin D1+ ATA B cell lymphoma

The biological relevance of this spontaneous mouse ATA B lymphoma to human MCL was still unclear. The majority of human MCL are cyclin D1 upregulated because of translocation of the cyclin D1 gene into the IgH locus, an event that may have occurred during initial B cell development stage (8). The Lin28–Let7 axis controls cyclin D1 expression (13, 14), and we found that mouse Lin28b+Let7b− B-1 B cell precursors initially expressed high levels of cyclin D1 transcripts as compared with adult B-2 precursors (Fig. 6A). Then, cyclin D1 expression was strongly reduced at the CD19+ B-lineage stage. However, cyclin D1 transcripts were still detectable at the newly generated immature B cell stage in liver (Lin28+Let7b−) at a higher level compared with B-2 development in bone marrow (Lin28−Let7b+) (Fig. 6A). As reported previously, cMyc, which promotes lymphoma generation, was also expressed at higher levels by B-1 immature B cells (Fig. 6A) (6). Although most mouse ATA B lymphomas that developed in old age (total 16 samples) did not show upregulated cyclin D1, we found one ATA B lymphoma (no. 72) showed a substantially increased level of cyclin D1 (Ccnd1) mRNA (Fig. 6B). Comparative genomic hybridization analysis and VH/D/JH sequence of this lymphoma revealed that this increased level of cyclin D1 transcript was not due to a translocation to IgH, as previously found in mouse cyclin D1+ preB or B lymphomas by amplification (43). In this no. 72 mouse, a continuous increase of ATA B cells occurred in PBL from adult to old age (4–14 mo) and the generation of CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma, similar to cyclin D1− CD11b+ ATA B lymphoma (Supplemental Fig. 3).

FIGURE 6.

Cyclin D1+ ATA B lymphoma. (A) Left, Lin28b and cyclin D1 qRT-PCR of day 1 liver versus 2-mo bone marrow B-lineage precursors (common lymphoid progenitor [CLP] and pre-proB) and CD19+B-lineage cells. Data are representative of three experiments. Right, qRT-PCR of immature B cells (CD19+AA4+IgM+IgD−) in day 1 liver (B-1) versus 2-mo BM (B-2). Lin28b and Let7b qRT-PCR representative of three experiments. Cyclin D1 (ccnd1) and cMyc (Myc) qRT-PCR; n = 5 in each group, mean ± SE. *p = 0.003, **p = 0.006. (B) Cyclin D1 qRT-PCR of ATA B lymphoma cells in ATAμκTg mouse spleen, and RT-PCR of no. 14 and no. 72 mouse RNA for cyclin D1 and IL-10 with WT FO B cells as control.

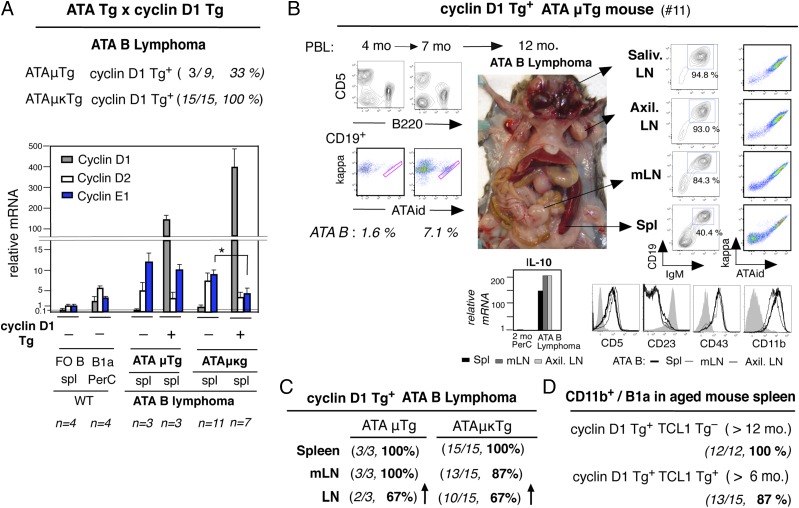

Diffuse mantle cell–like ATA B lymphoma development by overexpressing cyclin D1

To further assess the potential unique effects by increased cyclin D1 expression in ATA B cells, we crossed ATAμTg and ATAμκTg C.B17 mice with Eμ-cyclin D1 transgenic mice on the C57BL/6 background (16) and analyzed F1 hybrids. Expression of cyclin D1 Tg increased the incidence of ATA B lymphoma in ≥ 12-mo-aged ATAμTg and ATAμκTg mice (Fig. 7A, top), with extremely high cyclin D1 transcripts (Fig. 7A, bottom). Cyclin E1, which was frequently increased in spontaneous ATA B lymphomas without cyclin D1 increase, was expressed at lower levels in the context of cyclin D1 Tg (Fig. 7A, bottom). A distinguishing feature of ATA B tumors in cyclin D1 Tg+ mice compared with spontaneous cyclin D1 Tg− mice was the high frequency of peripheral lymph node (LN) involvement combined with spleen and mLN, indicative of a further diffused pattern of lymphoma. As shown by cyclin D1 Tg+ ATAμTg mouse no. 11 (Fig. 7B), circulating cyclin D1+ATA B cells were still low in PBL at 4 mo of age as found in normal ATAμTg mice, but their frequency increased slightly at 7 mo and progressed to disseminated ATA B lymphoma at 12 mo. ATA lymphoma cells were present at high frequencies in the different LNs, including in mLN and spleen (Fig. 7B, right). These lymphomas exhibited the CD19+CD5+IgM+CD23−CD43+ (also CD20+) phenotype characteristic of B1a cells, and they were CD11b+ with high levels of IL-10 mRNA (Fig. 7B). Similarly, the presence of the cyclin D1 Tg in ATAμκTg mice also resulted in disseminated ATA B lymphomas (Fig. 7C). These cyclin D1 Tg+ ATA B tumors resembling human MCL were predominantly CD11b+ IL-10+, similar to cyclin D1 Tg− spontaneous ATA B tumors. In the absence of ATA BCR Tg, although a slight increase of B1a cells was noted in PBL of older cyclin D1 Tg+ cells (6), they mostly failed to develop tumors. Coexpression of cyclin D1 Tg+ with TCL1 Tg+ in the absence of ATA Tg BCR resulted in a similar outcome, with the TCL1 Tg+ alone driving the development of leukemia/lymphoma but not the MCL type. However, in these cyclin D1 Tg+ mice, most B1a cells in spleen exhibited slightly increased CD11b+ levels, including in mice coexpressing TCL1 Tg (Fig. 7D). This indicated that increased cyclin D1 expression further promoted persistent CD11b/CD18 Mac-1 expression by ATA B cells to migrate. Taken together, the presence of the ATA BCR in combination with cyclin D1 promoted the development of diffuse B cell lymphoma as a B-1 developmental outcome in mice.

FIGURE 7.

Diffused ATA B lymphoma generation in ATA Tg mice with cyclin D1 Tg. (A) ATAμTg+/− and ATAμκTg+/− mice were crossed with Eμ-cyclin D1+/+ Tg mice. Top, ATA B lymphoma incidence in ATA Tg+/−cyclin D1 Tg+/− mice. Bottom, qRT-PCR of cyclin D1, D2, and E1. ATA B lymphoma data were from spleen. Values from 2-mo WT mouse spl FO B cell data were set to 0.1 for cyclin D1 and 1.0 for cyclin D2 and E2. Mean ± SE. *p = 0.002. (B) Results from cyclin D1 Tg+/− ATAμTg+/− mouse no. 11. Left, PBL analysis with ATA B (red) frequency in B cells. Right, 12-mo ATA B lymphoma stage. Flow cytometry analysis and IL-10 qRT-PCR (2-mo PerC B1a as 1). CD5, CD23, CD43, and CD11b level controls (gray) were of normal mouse spleen FO B cells. Salivary, axillary, and other LNs were all ATA B cell dominant. (C) Incidence of hyperplasia in tissues with ATA B cells in cyclin D1 Tg+ ATAμTg and ATAμκTg mice. Increased LN hyperplasia in both ATA Tg mice. (D) Cyclin D1 Tg+/+.B6 mice crossed with TCL1 Tg+/−.CB17 mice and F1 hybrids analysis. Incidence of CD11b+(med/lo) B1a cells in aged cyclin D1 Tg+/− mouse spleen B1a cells without or with TCL1 Tg. Under TCL1 Tg+ conditions, some mice started to increase B1a cells from 6 mo. spl, spleen.

Discussion

As an outcome of fetal/neonatal B-1 B cell development derived from a Lin28+Let7− B lineage precursor, B1a cells are predominantly playing positive roles in innate immunity in normal mice (22). In addition to natural Ab production, B1a cells also have the ability to produce IL-10 through TLR signaling, contributing to the prevention of uncontrolled inflammation (44–46). As shown in this study, at the initial neonatal stage, mature B1a cells are present in intestine, including in colon. The presence of B1a cells in neonatal colon could be important for immediate control of inflammation during increasing microflora development, similar to the role previously identified for neonatal IL-10–producing spleen B1a cells in controlling pathogenesis (46). B-1–derived B1a cells are continuously present in tissues and body cavity, circulate from neonatal to old age, and play a positive role throughout life. However, in aging mice, an increase in B1a cells in PBL can occur, and the expression of certain BCRs on distinct genetic backgrounds leads to leukemia/lymphoma. We showed in this study that expression of an ATA BCR by B1a cells in the C.B17 background led to frequent spontaneous generation of lymphoma in old-aged mice. Lin28+Let7− B-1 B cell precursors express higher levels of cyclin D1 transcripts than adult B-2 B cell precursors, and the transgenic overexpression of cyclin D1 by B cells promoted disseminated ATA B cell lymphoma development resembling human MCL. Thus, B-1–derived B1a cells have the capacity to become MCL-like neoplasia.

In normal mouse development, CD11b is expressed by B1a cells deposited in the body cavity but not in tissues (26). When TLR–type 1 IFN signaling occurs, expression of the Mac-1 subunits CD11b and CD18 by B1a cells allows adherence to endothelial cells by binding to ICAM-1 by CD11 and migration and attachment to tissues through CD18 (35). This migration has been observed by CD11b+ B1a cells in the pleural cavity, which accumulated in mediastinal LNs, following infection with influenza (31). Thus, CD11b-expressing B1a cells in the body cavity respond immediately to local infection by migrating from the body cavity to tissues and producing IL-10, analogous to migration to colon for preventing colitis (45). After providing immediate secretion of protective IL-10 in tissues, the proliferation of B1a cells is controlled by the tissue microenvironment. One of the CD11b ligands, complement C3 fragment iC3b, contributes to this control. iC3b decreases CD11b expression and leads to tolerance but inhibits apoptosis to maintain B1a cells in tissues (47, 48). IL-10 initially produced by B1a cells also normally autoregulates B1a cells by controlling their expansion (33). Thus, normal resident B1a cells in tissues are primarily CD11b− IL-10− and exhibit low proliferation. ATA B cells present in adult tissues were also CD11b− before lymphoma generation.

We postulate that the altered intestinal microenvironment in aging may have contributed to promoting persistent CD11b+IL-10+ expression to foster the generation of lymphoma. TLR signaling produces IL-10 by B1a cells (44) and also induces CD11b expression by CD11b− B1a cells in tissue with further increase of CD11b expression upon addition of IL-10, as shown in this study. A unique feature of spontaneously occurring ATA B cell lymphoma was the frequent association with mLN hyperplasia, and ATA B tumors in intestine PP also occurred (in 3/97 ATA B lymphoma) (Supplemental Fig. 4). These results suggest intestinal microenvironment can affect outcome. Costimulation with the TNF superfamily member B cell–activating factor (BAFF) abrogates the inhibitory controlling effect of IL-10 on B1a cells (33). Therefore, we postulate that in addition to TLR signal by intestinal microflora or viral pathogens, BAFF and/or another TNF superfamily member, APRIL (a proliferation-inducing ligand), both of which are present in intestine (49) as in other tissues, may have helped to retain increased expression of IL-10. Interestingly, it was previously found that mice expressing APRIL Tg developed B1a cell lymphoma at 9–12 mo of age, predominantly with progressive hyperplasia in mLN and PP, as well as disorganization of lymphoid tissues and increased IgA levels (50). Also, APRIL Tg mice expressed high levels of IL-10 in mLN B1a cells (50), resembling ATA B lymphoma. In humans, high expression of APRIL and BAFF has been reported in B cell malignancies, including MCL and CLL, suggesting a role for BAFF/APRIL in the development and maintenance of human B cell leukemia/lymphoma (51). Thus, the presence of BAFF and/or APRIL may be able to elicit prosurvival effects of autocrine IL-10 on B1a cells after TLR signaling, thereby increasing B1a cells by promoting CD11b retention to further migration, such as from intestine to mLN. Because cyclin D1 enhances DNA repair in addition to constitutive dysregulation of the cell cycle (39), increased cyclin D1 by CD11b+ B1a cells may have further promoted widespread dissemination of B1a cells into different tissues.

The expression of certain BCRs on distinct mouse genetic backgrounds leads to leukemia/lymphoma. The VH3609/Vk21 BCR that we study is polyreactive as are other antithymocyte reactive BCRs (52), and this ATA BCR can also bind to a subset of mature Thy-1+ T cells (25, 53). Because expression of the specific Thy-1 glycoform by mature T cells is at a lower level than on immature thymocytes (25, 53), the presence of mature T cells is not required for initial ATA B cell generation, self-renewal, and Ab production. The increase of ATA B cells during aging is also independent of CD40/CD40L signaling from T cells (6). However, increased ATA B cells may influence mature T cells by direct binding with the ATA BCR, thereby decreasing the T cell protective role in adaptive immunity, which could further contribute to increased capacity of ATA B cells to generate lymphoma. This spontaneous ATA B lymphoma occurred in our model in C.B17 mice. C.B17 mice are on the BALB/c background, and BALB/c mice are known to express a unique cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a allele in the Cdkn2a gene, leading to less effective reduction of G1 arrest by p16INK4a (54). Because the CDKN2A locus in humans is frequently deleted in MCL (55–57), this specific ATA BCR within the context of C.B17 mouse background genes may have increased susceptibility for spontaneous development of lymphomas. Similar to ATAμκTg.C.B17 mice, NZB mice have unique properties because they exhibit thymocytotoxic autoantibody production started from early in life (58) and increased incidence of B1a leukemia/lymphoma in aged mice (59). NZB mice contain significantly lower expression of the Cdkn2c gene encoding for p18INK4c, which is also the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (60). In the NZB background, the presence of autocrine IL-10 by B1a cells was found to be critical for expansion to become lymphoma because IL-10 knockout strongly decreased CD5+ B lymphoma incidence (59). Furthermore, autocrine IL-10 prevented original autoantibody production by B1a cells in NZB mice (61). As shown in this study, ATA B lymphoma in C.B17 mice also showed high expression of IL-10. Taken together, this indicates that maintenance of IL-10, which activates Stat3 (36, 38) under the distinct genetic backgrounds, plays an important role in the development of B1a lymphoma.

Human MCL involves the GI tract. Although human MCLs are not predominantly CD11b+, they have been shown to have autocrine IL-10 production and activated STAT3 (36, 62). Because some spontaneous ATA B lymphoma in mice did not express CD11b (Fig. 5A), CD11b reduction may have still occurred under the migrated tissue environment. In human CLL, although high expression of CD11b was originally reported (63), most CLL tumors exhibit heterogeneous expression of CD11b as also found in TCL1 Tg+ mice. However, human CLLs expressing CD11b+ have a higher probability of disease progression and poorer survival than CD11b− cases (64). These findings provide support that mouse ATA B lymphomas continuously expressing CD11b together with IL-10 and pStat3 have characteristics of further aggressive B lymphomas. In addition to leukemia/lymphoma generation, B-1–derived B1a cells can also generate IgA plasmacytoma in BALB/c mice (65), and it was reported that plasma cell tumor development in aged mice is inhibited under germ-free conditions (66). In this plasmacytoma model, when the p16INK4a allele in the Cdkn2a gene of BALB/c mice was altered to the resistant mouse allele, the mice became relatively resistant to generating plasmacytoma (54). In summary, the presence of microbial flora is likely to be playing an important role in promoting B-1–derived B cell lymphoma generation, together with expression of specific BCRs and the distinct genetic background. Increased cyclin D1 can further promote MCL-like neoplasia in aged mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jerry Adams for originally providing cyclin D1 Tg mice, Catherine Renner for help with histologic analysis, and Dr. Kerry Campbell for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01 CA129330 and R01 AI113320 (to K.H.), R01 AI026782 and R21 AI117429 (to R.R.H), and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- aPtC

- antiphosphatidylcholine

- ATA

- antithymocyte/Thy-1 autoreactive

- ATAid

- VH3609/Vk21-5 idiotype

- ATAμTg

- VH3609μ Tg

- ATAμκTg

- VH3609/Vk21-5 μκ Tg

- B1a

- murine CD5+ B cell

- BAFF

- B cell–activating factor

- CLL

- chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- FO B cell

- follicular B cell

- GI

- gastrointestinal

- LN

- lymph node

- MBL

- monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis

- MCL

- mantle cell lymphoma

- mLN

- mesenteric lymph node

- PerC

- peritoneal cavity

- PP

- Peyer patch

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- TCL1

- T cell leukemia 1

- Tg

- transgene

- Thy-1KO

- Thy-1 knockout

- VH11t

- VH11/D/JH1 knock-in mouse line

- WT

- wild type.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yuan J., Nguyen C. K., Liu X., Kanellopoulou C., Muljo S. A. 2012. Lin28b reprograms adult bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors to mediate fetal-like lymphopoiesis. Science 335: 1195–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y., Li Y. S., Bandi S. R., Tang L., Shinton S. A., Hayakawa K., Hardy R. R. 2015. Lin28b promotes fetal B lymphopoiesis through the transcription factor Arid3a. J. Exp. Med. 212: 569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy R. R., Hayakawa K., Shimizu M., Yamasaki K., Kishimoto T. 1987. Rheumatoid factor secretion from human Leu-1+ B cells. Science 236: 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su W., Yeong K. F., Spencer J. 2000. Immunohistochemical analysis of human CD5 positive B cells: mantle cells and mantle cell lymphoma are not equivalent in terms of CD5 expression. J. Clin. Pathol. 53: 395–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayakawa K., Hardy R. R., Stall A. M., Herzenberg L. A., Herzenberg L. A. 1986. Immunoglobulin-bearing B cells reconstitute and maintain the murine Ly-1 B cell lineage. Eur. J. Immunol. 16: 1313–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayakawa K., Formica A. M., Brill-Dashoff J., Shinton S. A., Ichikawa D., Zhou Y., Morse H. C., III, Hardy R. R. 2016. Early generated B1 B cells with restricted BCRs become chronic lymphocytic leukemia with continued c-Myc and low Bmf expression. J. Exp. Med. 213: 3007–3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayakawa K., Formica A. M., Colombo M. J., Shinton S. A., Brill-Dashoff J., Morse Iii H. C., Li Y. S., Hardy R. R. 2016. Loss of a chromosomal region with synteny to human 13q14 occurs in mouse chronic lymphocytic leukemia that originates from early-generated B-1 B cells. Leukemia 30: 1510–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jares P., Colomer D., Campo E. 2007. Genetic and molecular pathogenesis of mantle cell lymphoma: perspectives for new targeted therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7: 750–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez-Galán P., Dreyling M., Wiestner A. 2011. Mantle cell lymphoma: biology, pathogenesis, and the molecular basis of treatment in the genomic era. Blood 117: 26–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisenburger D. D., Armitage J. O. 1996. Mantle cell lymphoma-- an entity comes of age. Blood 87: 4483–4494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodig S. J., Shahsafaei A., Li B., Dorfman D. M. 2005. The CD45 isoform B220 identifies select subsets of human B cells and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Hum. Pathol. 36: 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh S. H., Thorsélius M., Johnson A., Söderberg O., Jerkeman M., Björck E., Eriksson I., Thunberg U., Landgren O., Ehinger M., et al. 2003. Mutated VH genes and preferential VH3-21 use define new subsets of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 101: 4047–4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li N., Zhong X., Lin X., Guo J., Zou L., Tanyi J. L., Shao Z., Liang S., Wang L. P., Hwang W. T., et al. 2012. Lin-28 homologue A (LIN28A) promotes cell cycle progression via regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), cyclin D1 (CCND1), and cell division cycle 25 homolog A (CDC25A) expression in cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 17386–17397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz J., Lorenz P., Gross G., Ibrahim S., Kunz M. 2008. MicroRNA let-7b targets important cell cycle molecules in malignant melanoma cells and interferes with anchorage-independent growth. Cell Res. 18: 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith M. R., Joshi I., Jin F., Al-Saleem T. 2006. Murine model for mantle cell lymphoma. Leukemia 20: 891–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodrug S. E., Warner B. J., Bath M. L., Lindeman G. J., Harris A. W., Adams J. M. 1994. Cyclin D1 transgene impedes lymphocyte maturation and collaborates in lymphomagenesis with the myc gene. EMBO J. 13: 2124–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz S. G., Labelle J. L., Meng H., Valeriano R. P., Fisher J. K., Sun H., Rodig S. J., Kleinstein S. H., Walensky L. D. 2014. Mantle cell lymphoma in cyclin D1 transgenic mice with Bim-deficient B cells. Blood 123: 884–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romaguera J. E., Medeiros L. J., Hagemeister F. B., Fayad L. E., Rodriguez M. A., Pro B., Younes A., McLaughlin P., Goy A., Sarris A. H., et al. 2003. Frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its clinical significance in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer 97: 586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen L., Shinton S. A., Hardy R. R., Hayakawa K. 2005. Association of B-1 B cells with follicular dendritic cells in spleen. J. Immunol. 174: 6918–6926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conger J. D., Sage H. J., Kawaguchi S., Corley R. B. 1991. Properties of murine antibodies from different V region families specific for bromelain-treated mouse erythrocytes. J. Immunol. 146: 1216–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawaguchi S. 1987. Phospholipid epitopes for mouse antibodies against bromelain-treated mouse erythrocytes. Immunology 62: 11–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grönwall C., Vas J., Silverman G. J. 2012. Protective roles of natural IgM antibodies. Front. Immunol. 3: 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardy R. R., Wei C. J., Hayakawa K. 2004. Selection during development of VH11+ B cells: a model for natural autoantibody-producing CD5+ B cells. Immunol. Rev. 197: 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayakawa K., Asano M., Shinton S. A., Gui M., Allman D., Stewart C. L., Silver J., Hardy R. R. 1999. Positive selection of natural autoreactive B cells. Science 285: 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayakawa K., Carmack C. E., Hyman R., Hardy R. R. 1990. Natural autoantibodies to thymocytes: origin, VH genes, fine specificities, and the role of Thy-1 glycoprotein. J. Exp. Med. 172: 869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells S. M., Kantor A. B., Stall A. M. 1994. CD43 (S7) expression identifies peripheral B cell subsets. J. Immunol. 153: 5503–5515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bos N. A., Bun J. C., Popma S. H., Cebra E. R., Deenen G. J., van der Cammen M. J., Kroese F. G., Cebra J. J. 1996. Monoclonal immunoglobulin A derived from peritoneal B cells is encoded by both germ line and somatically mutated VH genes and is reactive with commensal bacteria. Infect. Immun. 64: 616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ha S. A., Tsuji M., Suzuki K., Meek B., Yasuda N., Kaisho T., Fagarasan S. 2006. Regulation of B1 cell migration by signals through Toll-like receptors. J. Exp. Med. 203: 2541–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itakura A., Szczepanik M., Campos R. A., Paliwal V., Majewska M., Matsuda H., Takatsu K., Askenase P. W. 2005. An hour after immunization peritoneal B-1 cells are activated to migrate to lymphoid organs where within 1 day they produce IgM antibodies that initiate elicitation of contact sensitivity. J. Immunol. 175: 7170–7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macpherson A. J., Gatto D., Sainsbury E., Harriman G. R., Hengartner H., Zinkernagel R. M. 2000. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science 288: 2222–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waffarn E. E., Hastey C. J., Dixit N., Soo Choi Y., Cherry S., Kalinke U., Simon S. I., Baumgarth N. 2015. Infection-induced type I interferons activate CD11b on B-1 cells for subsequent lymph node accumulation. Nat. Commun. 6: 8991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y., Tung J. W., Ghosn E. E., Herzenberg L. A., Herzenberg L. A. 2007. Division and differentiation of natural antibody-producing cells in mouse spleen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 4542–4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sindhava V., Woodman M. E., Stevenson B., Bondada S. 2010. Interleukin-10 mediated autoregulation of murine B-1 B-cells and its role in Borrelia hermsii infection. PLoS One 5: e11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagerholm S. C., Varis M., Stefanidakis M., Hilden T. J., Gahmberg C. G. 2006. alpha-Chain phosphorylation of the human leukocyte CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1) integrin is pivotal for integrin activation to bind ICAMs and leukocyte extravasation. Blood 108: 3379–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solovjov D. A., Pluskota E., Plow E. F. 2005. Distinct roles for the alpha and beta subunits in the functions of integrin alphaMbeta2. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 1336–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baran-Marszak F., Boukhiar M., Harel S., Laguillier C., Roger C., Gressin R., Martin A., Fagard R., Varin-Blank N., Ajchenbaum-Cymbalista F., Ledoux D. 2010. Constitutive and B-cell receptor-induced activation of STAT3 are important signaling pathways targeted by bortezomib in leukemic mantle cell lymphoma. Haematologica 95: 1865–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bromberg J. F. Wrzeszczynska M. H. Devgan G. Zhao Y. Pestell R. G. Albanese C. Darnell J. E. Jr.. 1999. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell 98: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saraiva M., O’Garra A. 2010. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10: 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jirawatnotai S., Hu Y., Michowski W., Elias J. E., Becks L., Bienvenu F., Zagozdzon A., Goswami T., Wang Y. E., Clark A. B., et al. 2011. A function for cyclin D1 in DNA repair uncovered by protein interactome analyses in human cancers. Nature 474: 230–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayakawa K., Asano M., Shinton S. A., Gui M., Wen L. J., Dashoff J., Hardy R. R. 2003. Positive selection of anti-thy-1 autoreactive B-1 cells and natural serum autoantibody production independent from bone marrow B cell development. J. Exp. Med. 197: 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ansel K. M., Harris R. B., Cyster J. G. 2002. CXCL13 is required for B1 cell homing, natural antibody production, and body cavity immunity. Immunity 16: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wen L., Brill-Dashoff J., Shinton S. A., Asano M., Hardy R. R., Hayakawa K. 2005. Evidence of marginal-zone B cell-positive selection in spleen. Immunity 23: 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi C. F., Chattopadhyay S. K., Lander M., Kim Y., Fredrickson T. N., Hartley J. W., Morse H. C., III 1998. Expression of cyclin D1 in mouse B cell lymphomas of different histologic types and differentiation stages. Leuk. Res. 22: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Garra A., Chang R., Go N., Hastings R., Haughton G., Howard M. 1992. Ly-1 B (B-1) cells are the main source of B cell-derived interleukin 10. Eur. J. Immunol. 22: 711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimomura Y., Mizoguchi E., Sugimoto K., Kibe R., Benno Y., Mizoguchi A., Bhan A. K. 2008. Regulatory role of B-1 B cells in chronic colitis. Int. Immunol. 20: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X., Deriaud E., Jiao X., Braun D., Leclerc C., Lo-Man R. 2007. Type I interferons protect neonates from acute inflammation through interleukin 10-producing B cells. J. Exp. Med. 204: 1107–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobson A. C., Roundy K. M., Weis J. J., Weis J. H. 2009. Regulation of murine splenic B cell CR3 expression by complement component 3. J. Immunol. 183: 3963–3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sohn J. H., Bora P. S., Suk H. J., Molina H., Kaplan H. J., Bora N. S. 2003. Tolerance is dependent on complement C3 fragment iC3b binding to antigen-presenting cells. Nat. Med. 9: 206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterson L. W., Artis D. 2014. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14: 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Planelles L., Carvalho-Pinto C. E., Hardenberg G., Smaniotto S., Savino W., Gómez-Caro R., Alvarez-Mon M., de Jong J., Eldering E., Martínez-A C., et al. 2004. APRIL promotes B-1 cell-associated neoplasm. Cancer Cell 6: 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haiat S., Billard C., Quiney C., Ajchenbaum-Cymbalista F., Kolb J. P. 2006. Role of BAFF and APRIL in human B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Immunology 118: 281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Underwood J. R., McCall A., Csar X. F. 1996. Naturally-occurring anti-thymocyte autoantibody which identifies a restricted CD4+CD8+CD3-/lo/int thymocyte subpopulation exhibits extensive polyspecificity. Thymus 24: 61–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gui M., Wiest D. L., Li J., Kappes D., Hardy R. R., Hayakawa K. 1999. Peripheral CD4+ T cell maturation recognized by increased expression of Thy-1/CD90 bearing the 6C10 carbohydrate epitope. J. Immunol. 163: 4796–4804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang S. L., DuBois W., Ramsay E. S., Bliskovski V., Morse H. C., III, Taddesse-Heath L., Vass W. C., DePinho R. A., Mock B. A. 2001. Efficiency alleles of the Pctr1 modifier locus for plasmacytoma susceptibility. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campo E., Rule S. 2015. Mantle cell lymphoma: evolving management strategies. Blood 125: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dreyling M. H., Bullinger L., Ott G., Stilgenbauer S., Müller-Hermelink H. K., Bentz M., Hiddemann W., Döhner H. 1997. Alterations of the cyclin D1/p16-pRB pathway in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 57: 4608–4614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinyol M., Hernandez L., Cazorla M., Balbín M., Jares P., Fernandez P. L., Montserrat E., Cardesa A., Lopez-Otín C., Campo E. 1997. Deletions and loss of expression of p16INK4a and p21Waf1 genes are associated with aggressive variants of mantle cell lymphomas. Blood 89: 272–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shirai T., Mellors R. C. 1971. Natural thymocytotoxic autoantibody and reactive antigen in New Zealand black and other mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 68: 1412–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Czarneski J., Lin Y. C., Chong S., McCarthy B., Fernandes H., Parker G., Mansour A., Huppi K., Marti G. E., Raveche E. 2004. Studies in NZB IL-10 knockout mice of the requirement of IL-10 for progression of B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 18: 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Potula H. H., Xu Z., Zeumer L., Sang A., Croker B. P., Morel L. 2012. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Cdkn2c deficiency promotes B1a cell expansion and autoimmunity in a mouse model of lupus. J. Immunol. 189: 2931–2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baglaenko Y., Manion K. P., Chang N. H., Gracey E., Loh C., Wither J. E. 2016. IL-10 production is critical for sustaining the expansion of CD5+ B and NKT cells and restraining autoantibody production in congenic lupus-prone mice. PLoS One 11: e0150515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Visser H. P., Tewis M., Willemze R., Kluin-Nelemans J. C. 2000. Mantle cell lymphoma proliferates upon IL-10 in the CD40 system. Leukemia 14: 1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baldini L., Cro L., Calori R., Nobili L., Silvestris I., Maiolo A. T. 1992. Differential expression of very late activation antigen-3 (VLA-3)/VLA-4 in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 79: 2688–2693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tàssies D., Montserrat E., Reverter J. C., Villamor N., Rovira M., Rozman C. 1995. Myelomonocytic antigens in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 19: 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Masmoudi H., Mota-Santos T., Huetz F., Coutinho A., Cazenave P. A. 1990. All T15 Id-positive antibodies (but not the majority of VHT15+ antibodies) are produced by peritoneal CD5+ B lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 2: 515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McIntire K. R., Princler G. L. 1969. Prolonged adjuvant stimulation in germ-free BALB-c mice: development of plasma cell neoplasia. Immunology 17: 481–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.