Abstract

Pleural effusion (PE) is a common manifestation associated with certain chest diseases. However, there is no effective diagnostic marker with high sensitivity and specificity. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the diagnostic performance of several biomarkers in the use of detecting malignant pleural disorder. One hundred and fifty patients with a specific diagnosis of exudative PE were enrolled in this study and were divided into the benign PE group (n=93) and the malignant PE group (n=57). Thoracoscopy was conducted to identify the reasons for the PE. Biomarkers in pleural fluid and in sera were determined either by microparticle enzyme immunoassay [carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)], fluorescence immunoassay [procalcitonin (PCT)] or light-scattering turbidimetric immunoassay [C-reaction protein (CRP)]. Then, correlation analysis and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis individually or in combination were performed. The CRP and PCT levels were higher in benign PE than they were in malignant PE (PCT: P=0.017, P=0.032; CRP: P=0.001, P<0.001, respectively), while CEA levels were lower in benign PE than in malignant PE (CEA: P=0.001, P=0.001, respectively). During the ROC curve analysis, an optimal discrimination was identified by combining pleural CRP, pleural CEA and serum (s)PCT with an area under the curve of 0.973 (sensitivity, 98.9%; specificity, 89.5%). In the diagnosis of PE, there was no single biomarker that appeared to be adequately accurate. The combination of pleural CRP, pleural CEA and sPCT may represent an efficient diagnostic procedure for guiding the patient towards follow-up clinical treatment.

Keywords: PCT, CRP, CEA, biomarker, pleural effusion

Introduction

Pleural effusion (PE) is divided into exudative effusion and transudative effusion. Exudative effusion is predominantly caused by diseases such as infection or cancers. Transudative effusion is mainly caused by diseases such as heart failure, liver failure and kidney malfunction (1). A large proportion of pleural inflammation is caused by bacterial infection, especially mycobacterium tuberculosis accompanied by benign PE. By contrast, many types of tumours that metastasize to lung or lung cancer in situ are associated with malignant PE. Initially, cytological, biochemical and microbiological analyses were used to investigate PE types (2); however, these were insufficient to differentiate benign PE from malignant PE. In recent years, the diagnosis has been made with invasive techniques such as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and thoracoscopic biopsy (3). Nevertheless, the clinical use of thoracoscopy has been restricted, since some patients cannot tolerate anaesthesia including intubation or are unable to be evaluated because of serious conditions (4). Although the indications for thoracoscopy are increasing, it is contraindicated in unfit patients (5).

Recently, tumour markers have been widely used for the diagnosis of PE, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), cytokeratin 19 (CYFRA 21–1), CA125, CA153 and CA199. However, these markers are improper for clinical practice because of their low sensitivity and specificity (4,6–12).

Procalcitonin (PCT) is produced by extra-thyroidal organs such as the lung and liver after infections, especially bacterial infections (13,14). PCT is thought to be a vital marker in the diagnosis of sepsis (13–16). Therefore, PCT is often used to distinguish bacterial infections from other diseases (17–20). Reportedly, PCT is elevated in pneumonia and decreased in tuberculosis and malignant PE (21). Meanwhile, the acute-phase reactant protein C-reaction protein (CRP) is primarily produced by the liver (22). The level of CRP in PE can be used to distinguish parapneumonic effusion from other types of effusion (23). To increase the sensitivity and specificity of PE discrimination, we intended to evaluate the diagnostic performance of PCT, CRP and CEA for detecting malignant pleural disorders.

Materials and methods

Subjects

One hundred and fifty patients with a specific diagnosis of exudative PE at the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine were enrolled in this study from January 2016 to April 2017. Another group including 43 patients with exudative PE from December 2017 to March 2018 was considered to verify the effect of the combined biomarkers in detecting malignant pleural disorders. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. All subjects agreed the study and signed informed consent letters.

An initial diagnostic thoracocentesis for microbiological, biochemical, and cytological studies was performed in all patients, and thoracoscopy was conducted to identify the disorder. The determination of PE aetiology was based on criteria as follows: Malignant PEs were confirmed through cytological and/or histological examination, most originating from tumours metastasized to lung tissue or lung cancer in situ. Benign PEs were from empyema, pneumonia and tuberculosis patients. The levels of CRP, PCT and CEA in pleural fluid and serum were analysed in all patients before any treatment.

Measurement of PCT, CEA and CRP levels

Five millilitres of pleural fluid from each patient was collected in the course of thoracocentesis and/or pleural biopsy. The pleural fluid was centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants was obtained and stored at −20°C. Simultaneously, 5 ml of blood from each patient was obtained for serum samples. The levels of PCT were measured by a Getein1100 fluorescence immunity analyser (Getein Biotech, Inc., Nanjing, China) with a functional assay sensitivity of 0.1 ng/ml. The CRP levels were detected by a QuikRead go immunity analyser (Orion Diagnostica Oy, Inc., Espoo, Finland) with a functional assay sensitivity of 1.0 mg/l. The CEA levels were detected by a Unicel Dxi800 microparticle chemiluminescence immunity analyser (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) with a functional assay sensitivity of 0.1 ng/ml. All levels were analysed according to manufacturers' instructions.

Statistical analysis

Since the data were not normally distributed, they were expressed as medians (interquartile range). We used the Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test for nonparametric variables to compare the differences. McNemar's test was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the combined biomarkers. The P-values were corrected for the number of comparisons using the Bonferroni method, and all tests were two-tailed. Spearman's rank test was used for correlation assessments. ROCs were analysed to determine the optimal cut-off values, and the area under the curve (AUC) values were compared to select the variables that predict the differentiation. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical data and biological features of all the enrolled patients

A total of 150 patients were enrolled in this study. The benign group included 93 cases of benign PE: 25 cases of empyema, 41 cases of pneumonia and 27 cases of tuberculosis, aged 46–91 years. The malignant group included 57 cases of malignant PE: 28 cases of lung cancer and 29 cases of cancers metastasized to lung tissue, aged 43–92 years. The benign group was divided into 3 subgroups. The clinical data and biological features of the patients are shown in Table I. These two groups included 77 men and 73 women, and patients studied were mainly older than 40 years of age, with a mean age of 70 years. There were no differences in terms of age and sex between groups. Under ultrasound, a large overlap in pleural effusion capacity was found between the benign and malignant pleural disorders. Nevertheless, cases with a large amount of fluid were more common in malignant pleural disorders.

Table I.

Clinical data of the populations.

| Characteristic | Benign PE (n=93) | Malignant PE (n=57) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71 (53–85) | 69 (47–83) | ns |

| Sex, M/F | 48/45 | 29/28 | ns |

| PE capacity, ml | 267 (93–610) | 719 (114–1,580) | 0.041 |

| PE WBC, 103/µl | 640 (270–2,000) | 930 (450–1,800) | 0.485 |

| PE NE, % | 67 (30–83) | 70 (39–91) | 0.469 |

| Sera | |||

| CRP, mg/l | 41.0 (19.0–86.2) | 12.5 (5.0–33.2) | <0.001 |

| PCT, ng/ml | 0.64 (0.14–3.21) | 0.11 (0.10–0.17) | 0.032 |

| CEA, mg/l | 1.91 (1.00–3.12) | 10.82 (2.40–75.90) | 0.001 |

| Pleural fluid | |||

| CRP, mg/l | 20.0 (8.0–41.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 0.001 |

| PCT, ng/ml | 0.22 (0.10–1.39) | 0.11 (0.10–0.15) | 0.017 |

| CEA, mg/l | 1.27 (1.00–3.00) | 69.13 (13.20–499.33) | 0.001 |

| ADA, IU/l | 10.7 (4.5–38.8) | 9.0 (5.9–12.8) | 0.081 |

| LDH, IU/l | 293 (135–598) | 364 (212–790) | 0.448 |

The data are presented as the median (interquartile range); interquartile range, 25th to 75th percentile; P-values were obtained using the Mann-Whitney U test; CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; PE, pleural effusion; ADA, adenosine deaminase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WBC, white blood cell; NE, neutrophil granulocyte; ns, not significant; M, male; F, female.

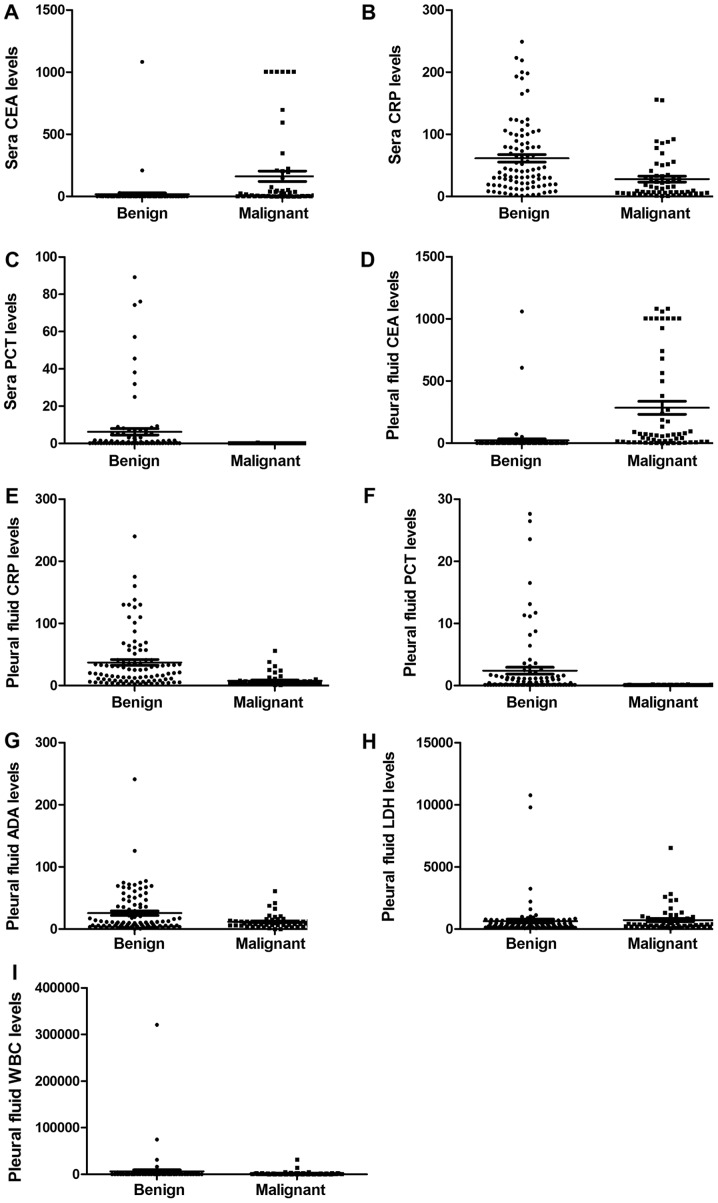

As shown in Table I and Fig. 1, the positive rate of white blood cell (WBC) count in all participating populations was 94.1%, while the positive rate of neutrophil (NE) was 73.8%. However, neither WBCs counts nor NE percentages were different between the groups. The pleural PCT, pleural CRP, sPCT and sCRP levels were markedly higher in benign patients. By contrast, the pleural CEA and sCEA levels were substantially lower in benign patients. Although the levels of adenosine deaminase (ADA) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in several tuberculosis PE patients were much higher, no significant differences were observed between the benign and malignant PEs.

Figure 1.

The comparative analysis of biomarkers in benign and malignant patients. (A) sCEA levels in benign and malignant patients. (B) sCRP levels in benign and malignant patients. (C) sPCT levels in benign and malignant patients. (D) Pleural CEA levels in benign and malignant patients. (E) Pleural CRP levels in benign and malignant patients. (F) Pleural PCT levels in benign and malignant patients. (G) Pleural ADA levels in benign and malignant patients. (H) Pleural LDH levels in benign and malignant patients. (I) Pleural WBC levels in benign and malignant patients. CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ADA, adenosine deaminase; s, sera.

Subgroup analysis of benign populations

To explore whether there were significant differences between pneumonia and empyema and tuberculous PE, a subgroup analysis of these groups was performed, and the statistical relevance of this analysis was negative, as shown in Table II.

Table II.

Clinical data of the benign patients.

| Characteristic | Pneumonia (n=41) | Empyema (n=25) | Tuberculous PE (n=27) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sera | |||

| CRP, mg/l | 41.2 (17.3–96.4) | 41.8 (29.1–106.5) | 37.5 (15.7–73.1) |

| PCT, ng/ml | 0.61 (0.11–3.16) | 0.60 (0.15–3.01) | 0.54 (0.12–3.37) |

| CEA, mg/l | 1.93 (1.00–3.58) | 1.81 (1.10–3.02) | 1.95 (1.06–3.52) |

| Pleural fluid | |||

| CRP, mg/l | 20.1 (6.2–49.3) | 27.8 (7.0–61.5) | 17.9 (3.0–37.1) |

| PCT, ng/ml | 0.21 (0.10–1.45) | 0.27 (0.10–1.18) | 0.29 (0.11–1.09) |

| CEA, mg/l | 1.24 (1.10–3.61) | 1.27 (1.02–3.30) | 1.34 (1.13–4.69) |

The data are presented as the median (interquartile range); interquartile range, 25th to 75th percentile; CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; PE, pleural effusion.

Descriptive analysis of parameters determined in sera and in pleural fluid

It was worth mentioning that the levels of PCT, CRP and CEA in both the pleural fluid and serum varied over a wide range. Similarly, the effusion/serum ratios of PCT, CRP and CEA also varied over a wide range, especially for CEA, nevertheless, there were no significant differences between benign and malignant patients, as shown in Table III.

Table III.

Descriptive analysis of parameters determined in sera and in pleural fluid and their PE/sera ratio (n=100).

| PE/Sera | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Sera range | Pleural fluid range | Benign | Malignant | P-value |

| CRP, mg/l | <1–200 | <1–240 | 0.86 (0.37–1.93) | 0.79 (0.46–1.80) | 0.078 |

| PCT, ng/ml | <0.1–89.2 | <0.1–27.6 | 1.23 (0.49–2.96) | 1.12 (0.31–2.77) | 0.091 |

| CEA, mg/l | <1–1083 | <1–1083 | 6.71 (1.05–21.17) | 6.02 (0.91–19.49) | 0.117 |

Data are presented as the median (interquartile range); interquartile range, 25th to 75th percentile; P-values were obtained using the Mann-Whitney U test. CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; PE, pleural effusion.

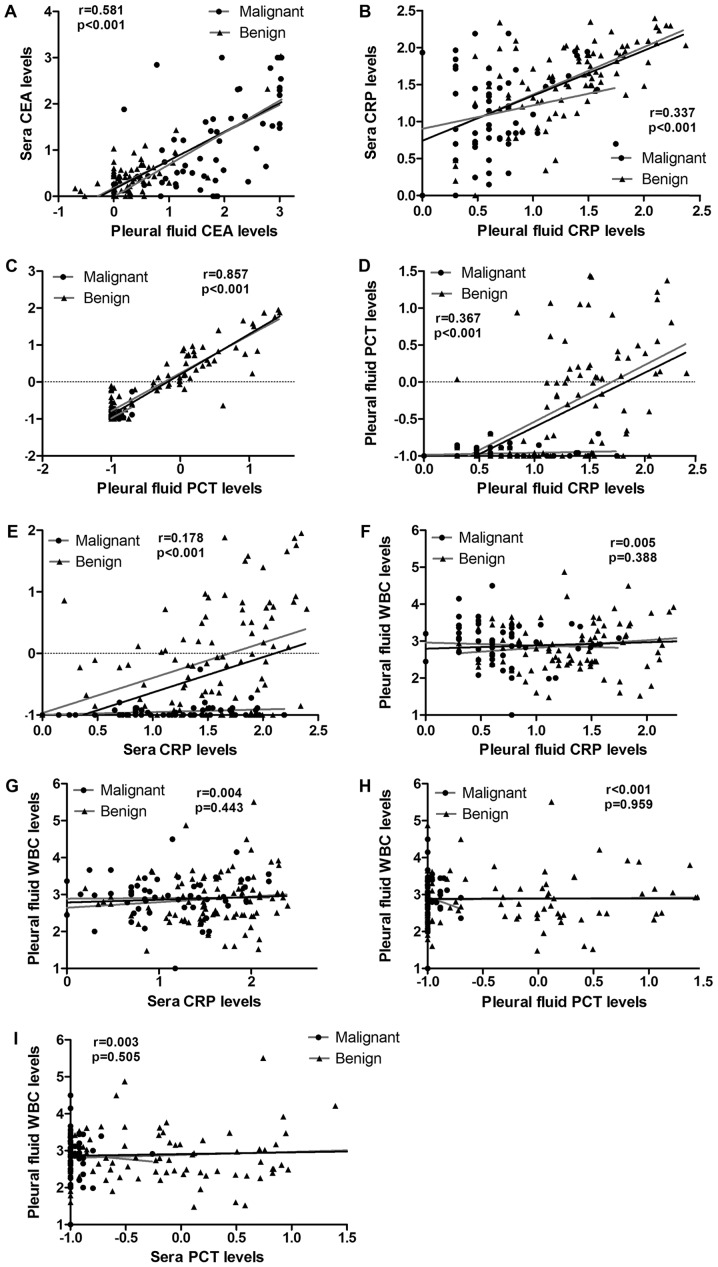

Correlation analysis of CRP, CEA, PCT and WBC in pleural fluid and in sera

To assay the values of the abovementioned markers to discriminate between benign and malignant PE, correlation analysis of CRP, CEA, PCT and WBC in the pleural fluid and serum were performed. As shown in Table IV and Fig. 2, a significant positive correlation between pleural PCT and sPCT was found (Spearman's r=0.857; P<0.001). Meanwhile, a positive correlation between the pleural CEA and sCEA levels was also found (Spearman's r=0.581; P<0.001); no correlation was found for CRP (Spearman's r=0.337; P<0.001). Additionally, there were no correlations between the pleural PCT and pleural CRP, or sPCT and sCRP levels (Spearman's r=0.367, P<0.001; Spearman's r=0.178; P<0.001, respectively).

Table IV.

Correlation analysis of CRP, CEA, PCT and WBC in pleural fluid and in sera.

| Parameter | Spearman's r | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Pleural CRP and sCRP | 0.337 | <0.001 |

| Pleural CEA and sCEA | 0.581 | <0.001 |

| Pleural PCT and sPCT | 0.857 | <0.001 |

| Pleural CRP and pleural PCT | 0.367 | <0.001 |

| sCRP and sPCT | 0.178 | <0.001 |

| Pleural CRP and pleural WBC | 0.005 | 0.388 |

| sCRP and pleural WBC | 0.004 | 0.443 |

| Pleural PCT and pleural WBC | <0.001 | 0.959 |

| sPCT and pleural WBC | 0.003 | 0.505 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; s, sera.

Figure 2.

The correlation analysis of biomarkers in benign and malignant patients. (A) The correlation analysis of sCEA and pleural CEA. (B) The correlation analysis of sCRP and pleural CRP. (C) The correlation analysis of sPCT and pleural PCT. (D) The correlation analysis of pleural PCT and pleural CRP. (E) The correlation analysis of sPCT and sCRP. (F) The correlation analysis of pleural WBC and pleural CRP. (G) The correlation analysis of pleural WBC and sCRP. (H) The correlation analysis of pleural WBC and pleural PCT. (I) The correlation analysis of pleural WBC and sPCT. CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ADA, adenosine deaminase; s, sera.

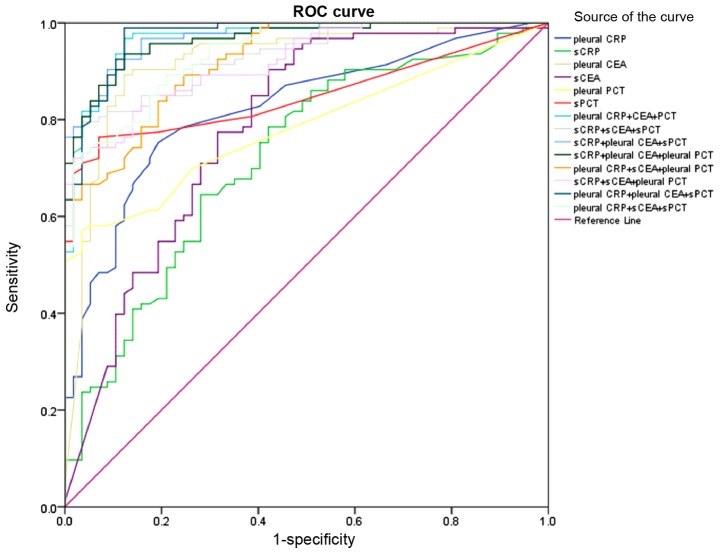

Use of cut-off values of individual biomarker or in combination for discrimination between benign and malignant PE

For individual biomarkers, discrimination was identified at a cut-off point of 5.70 mg/l for pleural CEA with an AUC of 0.872 (sensitivity: 89.2%, specificity: 87.7%), and 16.9 mg/l for sCRP with an AUC of 0.825 (sensitivity: 69.9%, specificity: 43.9%); the cut-off values and AUC values are displayed in Fig. 3 and Table V. As an individual predictor of malignant PE, pleural CEA exhibited a better diagnostic performance with a greater AUC value than did the other markers (P<0.001). Nevertheless, sCEA exhibited poor diagnostic performance compared to that of the others, with the lowest AUC value (P=0.001). For the discrimination between benign and malignant PE, CEA in pleural fluid and serum had better sensitivity than did other biomarkers (sensitivity: 90.3, 89.2%, respectively), as well as superior negative predictive value (NPV). By contrast, PCT in pleural fluid and serum exhibited lower sensitivity and higher specificity (sensitivity: 54.8, 63.1%; specificity: 96.5, 93.0%), as well as superior positive predictive value (PPV). On ROC curve analysis, optimal discrimination between benign and malignant PE was obtained by pleural CRP, pleural CEA and sPCT with area under the curve (AUC) of 0.973 (sensitivity: 98.9%, specificity: 89.5%), with the highest accuracy (95.3%). During our analysis, pleural CRP, pleural CEA and sPCT exhibited higher PPV and NPV. This result suggested that as the pleural CEA level increased, the sPCT and pleural CRP levels decreased, and the predictive value of malignant PE was credible. Conversely, as the pleural CEA levels declined, the sPCT and pleural CRP levels increased, and the predictive value for benign PE was credible. In conclusion, the predictive ability of combined biomarkers, including pleural CRP, pleural CEA and sPCT was much higher than were other combinations.

Figure 3.

ROC analysis of combined biomarkers and individual biomarker in pleural fluid and sera. ROC, receiver-operating characteristic; CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; s, sera.

Table V.

Use of cut-off values of individual biomarker or in combination for discrimination between benign and malignant PE.

| Variable | Cut-off value | P-value | AUC (95% CI), % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV/NPV, % | Accuracy, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleural CRP, mg/l | 7.50 | <0.001 | 0.786 (0.690–0.882) | 71.0 | 73.7 | 81.5/60.9 | 72.0 |

| sCRP, mg/l | 16.90 | <0.001 | 0.825 (0.733–0.917) | 69.9 | 43.9 | 67.0/47.2 | 60.0 |

| Pleural CEA, mg/l | 5.70 | <0.001 | 0.872 (0.784–0.960) | 89.2 | 87.7 | 92.2/83.3 | 88.7 |

| sCEA, mg/l | 5.53 | 0.001 | 0.708 (0.584–0.832) | 90.3 | 57.9 | 77.8/78.6 | 78.0 |

| Pleural PCT, ng/ml | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.783 (0.697–0.870) | 54.8 | 96.5 | 96.2/56.7 | 70.7 |

| sPCT, ng/ml | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.852 (0.779–0.925) | 63.1 | 93.0 | 94.4/67.9 | 80.7 |

| Pleural CRP + CEA + PCT | 0.954 (0.915–0.994) | 96.8 | 87.7 | 92.8/94.3 | 93.3 | ||

| sCRP + sCEA + sPCT | 0.926 (0.877–0.975) | 78.5 | 98.2 | 98.6/73.7 | 86.0 | ||

| sCRP + pleural CEA + sPCT | 0.971 (0.950–0.992) | 90.3 | 91.2 | 91.2/85.2 | 90.7 | ||

| sCRP + pleural CEA + pleural PCT | 0.965 (0.940–0.990) | 93.5 | 87.7 | 87.7/89.2 | 91.3 | ||

| Pleural CRP + sCEA + pleural PCT | 0.922 (0.882–0.962) | 89.2 | 75.4 | 75.4/81.1 | 84.0 | ||

| sCRP + sCEA + pleural PCT | 0.920 (0.880–0.960) | 73.1 | 96.5 | 96.5/68.8 | 82.0 | ||

| Pleural CRP+ pleural CEA + sPCT | 0.973 (0.951–0.995) | 98.9 | 89.5 | 89.5/98.1 | 95.3 | ||

| Pleural CRP + sCEA + sPCT | 0.937 (0.902–0.972) | 73.1 | 96.5 | 96.5/68.8 | 82.0 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; PE, pleural effusion; AUC, area under the curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; s, sera; CI, confidence interval.

Coincidence rate of combined biomarkers in detecting malignant pleural disorders

To see the effect of the combined biomarkers on detecting malignant pleural disorders, we verified the biomarkers in another group of patients. As before, we divided the patients into two groups. The benign group included 23 cases of benign PE: 6 cases of empyema, 14 cases of pneumonia and 3 cases of tuberculosis. The malignant group included 20 cases of malignant PE: 12 cases of lung cancer and 8 cases of cancers metastasized to lung. In accordance with the combined biomarkers, 19 cases were verified as benign among 23 cases of benign pleural disorders. Meanwhile, 18 cases were verified as malignant among 20 cases of malignant pleural disorders (Table VI). Cytological and/or histological examinations were used to confirm the nature of the pleural disorder. The coincidence rate was 86.0%. According to McNemar's test, there were no differences in the predictive value of the combined biomarkers compared to that of the golden standard. The biomarkers were particularly helpful in detecting malignant pleural disorders.

Table VI.

Coincidence rate of combined biomarkers in detecting malignant pleural disorders.

| Golden standard | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleural CRP + pleural CEA + sPCT | + | - | Total, n |

| + | 18 | 4 | 22 |

| – | 2 | 19 | 21 |

| Total, n | 20 | 23 | 43 |

P-value=0.687, McNemar's test; CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; s, sera; n, number.

Discussion

The conventional cytology method is deficient for diagnosis of the types of PE, especially for distinguishing malignant PE from benign PE (2,24–26). In recent years, research has been done to find an effective diagnosis method. Individual tumour marker analysis cannot provide an accurate diagnosis to determine whether a disease in a patient with PE is malignant or not. Generally, it is due to low sensitivity and specificity. Over the past decade, there have been many reports regarding the clinical utility of tumour markers in PE diagnosis (4,7,9,11,27–29), however, the sensitivity and specificity of these markers for discriminating between benign and malignant PE remain controversial (28). Sometimes, the combination of inappropriate tumour markers was useless, especially when the primary tumour site was unknown (25).

In our study, we found that CEA levels both in pleural fluid and in serum were elevated in malignant PE patients. Furthermore, as a single biomarker, pleural CEA was much better at discriminating between benign and malignant PE because of its greater AUC area. However, it restricted its usefulness to discrimination with low specificity. As a consequence, it is extremely important to find some reliable and rapid markers, or combinations of markers, that are capable of discriminating malignant from benign PE. Therefore, some indicators other than tumour markers are recommended by this study. Due to the main cause of exudative pleural effusion being inflammation or tumour, we used inflammatory markers in combination with tumour markers in order to improve the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in discrimination between benign and malignant PE.

In the present study, some inflammation indicators, including PCT and CRP, were chosen. However, PCT was different from CRP because of its different response to antibiotic therapy. The reliability of these indicators used alone or in combination as diagnostic markers was investigated. As an acute-phase reaction protein, CRP was used to screen for inflammation, including pleural infections. However, some studies reported that CRP exhibited low sensitivity and specificity for predicting lower respiratory tract infections (30). In our study, CRP was superior to PCT in terms of sensitivity but was inferior to PCT in terms of specificity. On the other hand, CRP was superior to PCT in terms of NPV but was inferior to PCT in terms of PPV. As an inflammatory biomarker, PCT is more rapid than is CRP for the detection of inflammation (31–33). Furthermore, pleural PCT exhibited the highest specificity for discrimination between benign and malignant PE. We found that there was no correlation between PCT and CRP levels in pleural fluid and serum in our study. To elevate the sensitivity, it was necessary to combine these inflammatory biomarkers.

According to our study, both PCT and CRP levels were significantly higher in benign PE patients than in malignant PE patients, whether in the pleural fluid or in serum. To evaluate the diagnostic value of the above-mentioned biomarkers, we performed ROC analysis. The results revealed that the combined biomarkers, including pleural CRP, pleural CEA and sPCT, were much more valuable than were any individual biomarker, while improving the diagnostic sensitivity, specificity and accuracy.

In conclusion, our data demonstrated that combinations of biomarkers, including pleural CRP, pleural CEA and sPCT had better diagnostic performance. Although we evaluated the value of combined biomarkers, there were limitations. As mentioned above, almost all malignant PE patients resulted from tumours, some of whom may have had accompanying pneumonia or empyema. Lack of differentiation in grouping might have influenced our findings. Further studies are necessary to validate our results.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81603358). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the paper.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

WG and WQ designed the study. MJ, XZ and JD conducted the experiments and data analysis. MJ interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. SQ and FM were involved in sample preparation, patient data collection and interpretation. JD performed statistical analysis. All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethical Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Consent for publication

All subjects gave written informed consent for the publication of any associated data and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Braunschweig T, Chung JY, Choi CH, Cho H, Chen QR, Xie R, Perry C, Khan J, Hewitt SM. Assessment of a panel of tumor markers for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant effusions by well-based reverse phase protein array. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maskell NA, Butland RJ, Pleural Diseases Group, Standards of Care Committee, British Thoracic Society BTS guidelines for the investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults. Thorax. 2003;58(Suppl 2):ii8–ii17. doi: 10.1136/thx.58.suppl_2.ii8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon DW, Cho JH, Choi YS, Kim J, Kim HK, Zo JI, Shim YM. Predictors of survival in patients who underwent video-assisted thoracic surgery talc pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Thorac Cancer. 2016;7:393–398. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porcel JM, Vives M, Esquerda A, Salud A, Pérez B, Rodríguez-Panadero F. Use of a panel of tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 15-3, and cytokeratin 19 fragments) in pleural fluid for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant effusions. Chest. 2004;126:1757–1763. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catarino PA, Goldstraw P. The future in diagnosis and staging of lung cancer: Surgical techniques. Respiration. 2006;73:717–732. doi: 10.1159/000095901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu P, Huang G, Chen Y, Zhu C, Yuan J, Sheng S. Diagnostic utility of pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA 21-1 in patients with pleural effusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2007;21:398–405. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang QL, Shi HZ, Qin XJ, Liang XD, Jiang J, Yang HB. Diagnostic accuracy of tumour markers for malignant pleural effusion: A meta-analysis. Thorax. 2008;63:35–41. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.077958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryu JS, Lee HJ, Cho JH, Han HS, Lee HL. The implication of elevated carcinoembryonic antigen level in pleural fluid of patients with non-malignant pleural effusion. Respirology. 2003;8:487–491. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alataş F, Alataş O, Metintaş M, Colak O, Harmanci E, Demir S. Diagnostic value of CEA, CA 15-3, CA 19-9, CYFRA 21-1, NSE and TSA assay in pleural effusions. Lung Cancer. 2001;31:9–16. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(00)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villena V, López-Encuentra A, Echave-Sustaeta J, Martín-Escribano P, Ortuño-de-Solo B, Estenoz-Alfaro J. Diagnostic value of CA 549 in pleural fluid. Comparison with CEA, CA 15.3 and CA 72.4. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shitrit D, Zingerman B, Shitrit AB, Shlomi D, Kramer MR. Diagnostic value of CYFRA 21-1, CEA, CA 19-9, CA 15-3, and CA 125 assays in pleural effusions: Analysis of 116 cases and review of the literature. Oncologist. 2005;10:501–507. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-7-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Chang JH. Diagnostic utility of serum and pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen, neuron-specific enolase, and cytokeratin 19 fragments in patients with effusions from primary lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:2298–2303. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehanic S, Baljic R. The importance of serum procalcitonin in diagnosis and treatment of serious bacterial infections and sepsis. Mater Sociomed. 2013;25:277–281. doi: 10.5455/msm.2013.25.277-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uzzan B, Cohen R, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Perret GY. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic test for sepsis in critically ill adults and after surgery or trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1996–2003. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000226413.54364.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nijsten MW, Olinga P, The TH, de Vries EG, Koops HS, Groothuis GM, Limburg PC, ten Duis HJ, Moshage H, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Procalcitonin behaves as a fast responding acute phase protein in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:458–461. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wacker C, Prkno A, Brunkhorst FM, Schlattmann P. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:426–435. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunkhorst R, Eberhardt OK, Haubitz M, Brunkhorst FM. Procalcitonin for discrimination between activity of systemic autoimmune disease and systemic bacterial infection. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(Suppl 2):S199–S201. doi: 10.1007/s001340051144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joo K, Park W, Lim MJ, Kwon SR, Yoon J. Serum procalcitonin for differentiating bacterial infection from disease flares in patients with autoimmune diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1147–1151. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buhaescu I, Yood RA, Izzedine H. Serum procalcitonin in systemic autoimmune diseases-where are we now? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SE. Serum procalcitonin is a candidate biomarker to differentiate bacteremia from disease flares in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver. 2016;10:491–492. doi: 10.5009/gnl16272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CY, Hsiao YC, Jerng JS, Ho CC, Lai CC, Yu CJ, Hsueh PR, Yang PC. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin in pleural effusions. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Xie J, Guo F, Longhini F, Gao Z, Huang Y, Qiu H. Combination of C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and sepsis-related organ failure score for the diagnosis of sepsis in critical patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:51. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izhakian S, Wasser WG, Fox BD, Vainshelboim B, Kramer MR. The diagnostic value of the pleural fluid C-reactive protein in parapneumonic effusions. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:7539780. doi: 10.1155/2016/7539780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu C, Yu L, Zhan P, Zhang Y. Elevated pleural effusion IL-17 is a diagnostic marker and outcome predictor in lung cancer patients. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:23. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-19-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonangelo L, Sales RK, Corá AP, Acencio MM, Teixeira LR, Vargas FS. Pleural fluid tumour markers in malignant pleural effusion with inconclusive cytologic results. Curr Oncol. 2015;22:e336–e341. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Huang L, Tang H, Zhong N, He J. Pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen as a biomarker for the discrimination of tumor-related pleural effusion. Clin Respir J. 2017;11:881–886. doi: 10.1111/crj.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaspar MJ, de Miguel J, García Díaz JD, Díez M. Clinical utility of a combination of tumour markers in the diagnosis of malignant pleural effusions. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2947–2952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina R, Bosch X, Auge JM, Filella X, Escudero JM, Molina V, Solé M, López-Soto A. Utility of serum tumor markers as an aid in the differential diagnosis of patients with clinical suspicion of cancer and in patients with cancer of unknown primary site. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:463–474. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miédougé M, Rouzaud P, Salama G, Pujazon MC, Vincent C, Mauduyt MA, Reyre J, Carles P, Serre G. Evaluation of seven tumour markers in pleural fluid for the diagnosis of malignant effusions. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blasi F, Stolz D, Piffer F. Biomarkers in lower respiratory tract infections. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castelli GP, Pognani C, Meisner M, Stuani A, Bellomi D, Sgarbi L. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein during systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis and organ dysfunction. Crit Care. 2004;8:R234–R242. doi: 10.1186/cc2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meidani M, Khorvash F, Abolghasemi H, Jamali B. Procalcitonin and quantitative C-reactive protein role in the early diagnosis of sepsis in patients with febrile neutropenia. South Asian J Cancer. 2013;2:216–219. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.119913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magrini L, Travaglino F, Marino R, Ferri E, de Berardinis B, Cardelli P, Salerno G, Di Somma S. Procalcitonin variations after Emergency Department admission are highly predictive of hospital mortality in patients with acute infectious diseases. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(Suppl 1):S133–S142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.