Abstract

Period circadian regulator (Per)1 and Per2 genes are involved in the molecular mechanism of the circadian clock, and exhibit tumor suppressor properties. Several studies have reported a decreased expression of Per1, Per2 and Per3 genes in different types of cancer and cancer cell lines. Promoter methylation downregulates Per1, Per2 or Per3 expression in myeloid leukemia, breast, lung, and other cancer cells; whereas histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) upregulate Per1 or Per3 expression in certain cancer cell lines. However, the transcriptional regulation of Per1 and Per2 in cancer cells by chromatin modifications is not fully understood. The present study aimed to determine whether HDACi regulate Per1 and Per2 expression in gastric cancer cell lines, and to investigate changes in chromatin modifications in response to HDACi. Treatment of KATO III and NCI-N87 human gastric cancer cells with sodium butyrate (NaB) or Trichostatin A (TSA) induced Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner. Chromatin immunoprecipitaion assays revealed that NaB and TSA decreased lysine 9 trimethylation on histone H3 (H3K9me3) at the Per1 promoter. TSA, but not NaB increased H3K9 acetylation at the Per2 promoter. It was also observed that binding of Sp1 and Sp3 to the Per1 promoter decreased following NaB treatment, whereas Sp1 binding increased at the Per2 promoter of NaB- and TSA-treated cells. In addition, Per1 promoter is not methylated in KATO III cells, while Per2 promoter was methylated, although NaB, TSA, and 5-Azacytidine do not change the methylated CpGs analyzed. In conclusion, HDACi induce Per1 and Per2 expression, in part, through mechanisms involving chromatin remodeling at the proximal promoter of these genes; however, other indirect mechanisms triggered by these HDACi cannot be ruled out. These findings reveal a previously unappreciated regulatory pathway between silencing of Per1 gene by H3K9me3 and upregulation of Per2 by HDACi in cancer cells.

Keywords: gastric cancer cells, clock genes, period circadian regulator, period circadian regulator 2, histone deacetylase inhibitors, chromatin remodeling

Introduction

Circadian rhythms are biological rhythms with a periodicity close to 24 h. In mammals, these rhythms are generated by a master biological clock, located in the hypothalamus and by clocks localized in peripheral cells (1). At the molecular level, circadian clocks are operated by transcriptional/translational feedback loops involving a set of genes called ‘clock genes’ (2,3). Clock genes operate like oscillators, modulating rhythmic transcription of a large number of genes in all cells by a mechanism that relies on coordinated chromatin remodeling events (4,5). Situations that alter the normal expression pattern of the clock genes have important repercussions at the systemic, cellular and molecular levels (6).

The maintenance of the molecular mechanism of the circadian clockwork has a profound influence on human health, and its alteration has frequently been associated with multiple diseases, including cancer (7–12). Several in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that, in addition to their main role within the molecular mechanism of the circadian clock, Period circadian regulator (Per)1 and Per2 genes can also function as tumor suppressors due to their involvement in cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle control, and DNA damage response (13–22). Targeted ablation of Per2 leads to the development of malignant lymphomas (13), whereas its ectopic expression in cancer cell lines results in growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and loss of clonogenic ability (15,18).

Accumulating evidence suggests that deregulation or significantly decreased expression of Per1 and Per2 genes in humans is associated with increased risk of breast, prostate, ovarian, endometrial, pancreatic, colorectal, gastric, liver, skin, lung, and head and neck cancers, leukemia, lymphomas, and glioma (23–41). Decreased expression of Per1 or Per2 genes has been associated with promoter hypermethylation in breast, endometrial, and non-small lung cancer cells (23,27,35). On the other hand, treatment of non-small cell lung cancer cells and other cancer cell lines with SAHA, an HDACi, induce the expression of Per1 gene (35), whereas TSA induced the expression of Per3 in myeloid leukemia cells (41); however, the role of HDACi on Per2 expression has not been tested, neither their role on Per1 and Per2 expression in gastric cancer cells. Studies in rodents have shown that histone H3 acetylation is of great relevance to maintain the activation and rhythmic expression of clock genes in liver cells (42).

Despite this evidence, the transcriptional regulation of Per1 and Per2 genes by epigenetic modifications is not fully understood, and the role of HDACi on Per1 and Per2 expression in gastric cancer cells has not been explored. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether HDACi regulate the expression of Per1 and Per2 genes in two human gastric cancer cell lines, and to determine histone-specific modifications in response to the HDACi treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatments with HDACi

KATO III and NCI-N87 human gastric carcinoma cells were acquired from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). KATO III cells were grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin, and 70 mg/l kanamycin. NCI-N87 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin and 70 mg/l kanamycin. Both cell lines were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. Exponentially growing cells were trypsinized and seeded in 6-well plates; when cells reached 70–80% confluence by microscopic examination (day 2 or 3 post-plating), the medium was changed, and sodium butyrate (NaB) (1, 2 or 3 mM) or trichostatin A (TSA) (50, 100 or 150 nM) were added. Cells were treated during 48 or 96 h with these reagents, replacing the medium with inhibitors every 24 h.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

KATO III and NCI-N87 cells treated during 48 or 96 h as described above, were washed twice with 1× PBS, then 1 ml of Trizol reagent was added to isolate total cellular RNA, according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the RNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Total RNA (1 µg) was reverse-transcribed using 200 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase and 50 pmoles of random hexamers in a final volume of 20 µl, according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

RT-qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate, containing 6 µl of 2× SYBR Green qPCR reaction mix (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1 µl of cDNA from each sample, and 5 pmol of each primer (forward and reverse) for Per1 or Per2 (Table I), in a final volume of 12 µl. RT-qPCR reactions were run as follow: 2 min at 50°C, 8.5 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min, followed by a dissociation analysis, in a 7500 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reactions with primers for GAPDH and ACTB were used as internal control (Table I). The efficiencies of RT-qPCR reactions were determined with the LinReg program (43), and the relative mRNA expression levels were calculated according to the method described by Pfaffl (44). The expression of Per1 and Per2 genes in control cells, without treatment, was considered as one.

Table I.

Primers for reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction and promoter analysis of Per1 and Per2 genes.

| Gene | Genbank accession no. | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER1 | NM_002616.2 | GGACATGACCTCTGTGCTGA | CATCAGGGTGACCAGGATCT | 3,688–3,887 |

| PER2 | NM_022817.2 | ACAGCTTTGGCTTCTGGTGT | TATTGGCCATCATGGTCTGA | 4,574–4,774 |

| GAPDH | NM_002046.5 | GTCAGTGGTGGACCTGACCT | TGAGGAGGGGAGATTCAGTG | 908-1,307 |

| ACTB | NM_001101.3 | TCCCTGGAGAAGAGCTACGA | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG | 787–980 |

| PER1p | – | TGTCTCTCCCCTCCTCTCAAa | AGATACGCTGCGCCTCTTTAa | −437 to −241 |

| PER2p | – | AGGAACCGACGAGGTGAAC | CCGCTGTCACATAGTGGAAA | −410 to −217 |

Primers were designed with Primer3 software

correspond to those reported by Gery et al (35). Per, Period circadian regulator; ACTB, β-actin; PER1/2p, Per1 and 2 gene promoter.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described (45). After cross-linking, cell lysates were sonicated on ice, soluble chromatin (equivalent to 50 µg of DNA) was pre-cleared with protein A/G plus-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) and then incubated overnight at 4°C on a Nutator platform with 2 µg of antibodies to H3 modifications (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), or with antibodies to Sp1 and Sp1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The immunoprecipitates were recovered by incubation with protein A/G agarose beads and washed sequentially for 5 min with low-salt buffer, high-salt buffer, LiCl wash buffer; and twice with TE buffer. Immunoprecipitated DNA was eluted, then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with RNase A, followed by overnight incubation at 55°C with proteinase K. DNA was reverse cross-linked and extracted with phenol, phenol-chloroform, and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, then precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 20 µl of H2O. Input samples (equivalent to 5 µg of DNA) were resuspended in 20 µl of H2O after reversal cross-linking and ethanol precipitation. PCR was conducted with 1 µl of immunoprecipitates or input samples, 10 µl of 2× PCR reaction mix (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), 5 pmoles of each primer for the Per1 or Per2 promoter (Table I), 1 µl of DMSO, and water up to 20 µl; with the following program: 3 min at 95°C, 30 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C, 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining with a XR 170–8170 photo documentation station (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Methylation specific PCR (MS-PCR)

KATO III cells were treated with 3 mM NaB or 100 nM TSA for 48 or 96 h with 5 µM of 5-Aza-2′-deoxycitydine (Aza). Cells were then lysed and treated with sodium bisulfite, followed by the DNA purification with the kit EZ-DNA Methylation-Direct (Zymo Research Corp., Irvine, CA, USA), following the directions from the manufacturer. Bisulfite-modified DNA was used to perform methylation-specific PCR (MS-PCR) using specific primers to distinguish methylated and unmethylated forms of Per1 and Per2 promoters, as reported (41). PCR reactions were conducted with 1 µl of modified DNA, 10 µl of 2× PCR mix (Promega Corporation), 5 pmoles of sense and antisense primers in a final volume of 20 µl. Cycling parameters were as described above, except that the annealing temperature was 56–62°C, according to the Tm of each primer set (41). PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels, visualized and documented as described above.

In silico analysis

In silico analysis to search for potential Sp1 and Sp3 binding sites at the Per1 and Per2 promoters was done using the JASPAR database (46).

Statistical analysis

RT-qPCR data were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test, except those obtained with Aza treatment that were analyzed with a U-Mann Whitney test, as they did not fit a normal distribution, whereas data from ChIP assays were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey post-hoc test, using the Statistica 7 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered significant. Plots were done with Sigmaplot 10.0 software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA USA).

Results

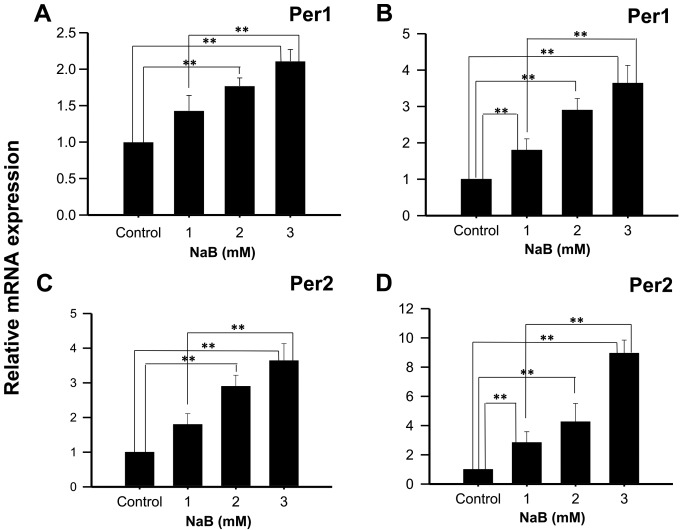

Treatment of KATO III cells with NaB or TSA induce Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression

KATO III cells treated with 2 or 3 mM NaB during 48 h showed a significant increase in Per1 mRNA expression, compared to control cells (1.77±0.11, and 2.11±0.16 fold higher, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 1A), and with 1, 2 and 3 mM NaB during 96 h (2.89±0.60; 3.79±0.73, and 4.84±0.40 fold higher, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 1B). Similarly, a significant induction in Per2 mRNA expression was found in KATO III cells treated with 2 or 3 mM NaB for 48 h compared to control cells (2.90±0.32 and 3.64±0.49 fold higher, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 1C), as well as with 1, 2 or 3 mM NaB for 96 h (2.84±0.74; 4.36±1.25 and 8.85±1.03 fold higher, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 1D). Significant differences were also found between cells treated with 1 and 3 mM NaB for 48- and 96-h (P<0.01).

Figure 1.

NaB induces the mRNA expression of Per1 and Per2 in human KATO III gastric cancer cells. KATO III cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of NaB for (A and C) 48 or 96 h (B and D), then Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression was determined by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. **P<0.01, as indicated. NaB, sodium butyrate; Per, period circadian regulator.

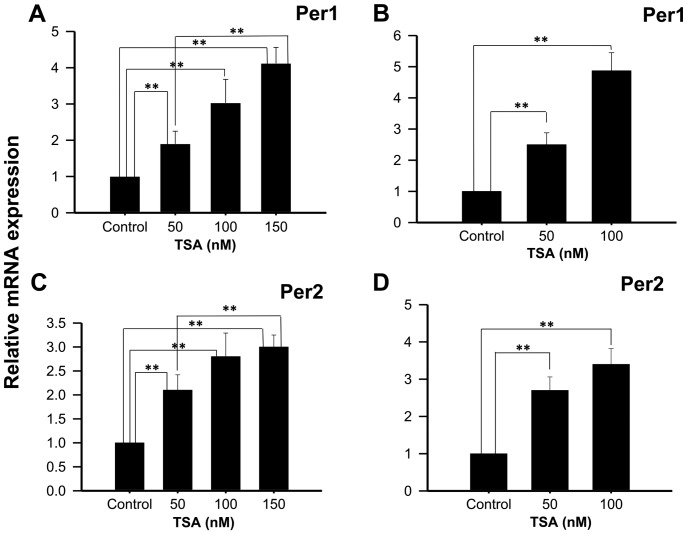

Experiments performed with 50, 100 or 150 nM TSA, a potent and specific class I and IIa HDACi, show increased Per1 mRNA expression at 48 h (1.90±0.35; 3.03±0.65 and 4.12±0.54 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 2A), as well as with 50 or 100 nM TSA for 96 h (2.5±0.38 and 4.87±0.58 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 2B). Similarly, significant increases in Per2 mRNA expression were found in KATO III cells treated with 50, 100 or 150 nM TSA for 48 h compared to control untreated cells (2.1±0.32±0.49 and 3±2.3±0.25, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 2C), as well as with 50 or 100 nM TSA for 96 h compared to control untreated cells (2.7±0.28; 3.4±0.33, respectively; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

TSA induces the mRNA expression of Per1 and Per2 in human KATO III gastric cancer cells. KATO III cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TSA for (A and C) 48 or (B and D) 96 h, then Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression was determined by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. **P<0.01, as indicated. Per, period circadian regulator; TSA, Trichostatin A.

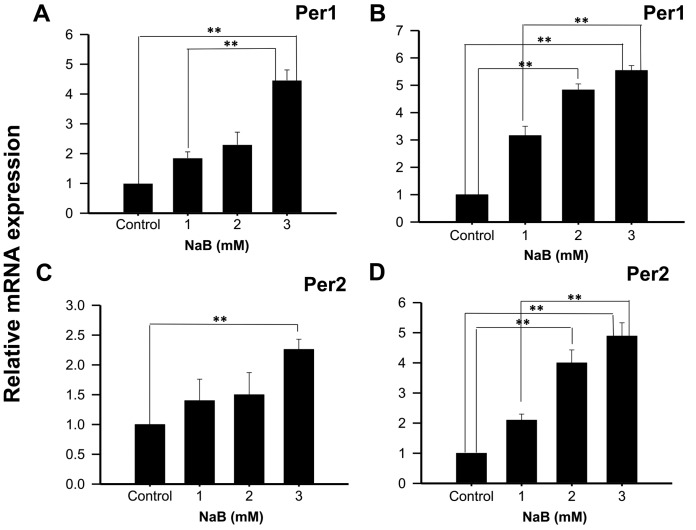

Treatment of NCI-N87 cells with NaB or TSA induce the expression of Per1 and Per2 mRNA

With the intention to show that the effect observed in KATO III cells was not cell line-specific, Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression was also analyzed in NCI-N87 cells treated with NaB or TSA during 48 or 96 h. The results show a significant increase in Per1 mRNA expression in cells treated with 3 mM NaB for 48 h (4.46±0.35 fold higher than control untreated cells; P<0.01; Fig. 3A). Extending the exposure time to 96 h with 2 and 3 mM NaB induced Per1 expression (4.83±0.22 and 5.54±0.18 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 3B). Significant differences were also found in Per2 mRNA expression with 3 mM NaB at 48 h (2.26±0.17 fold higher than control untreated cells; P<0.01; Fig. 3C), and with 2 and 3 mM at 96 h (4.00±0.38 and 4.89±0.36 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

NaB induces the mRNA expression of Per1 and Per2 in human NCI-N87 gastric cancer cells. NCI-N87 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of NaB for (A and C) 48 or (B and D) 96 h, then Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression was determined by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. **P<0.01, as indicated. NaB, sodium butyrate; Per, period circadian regulator.

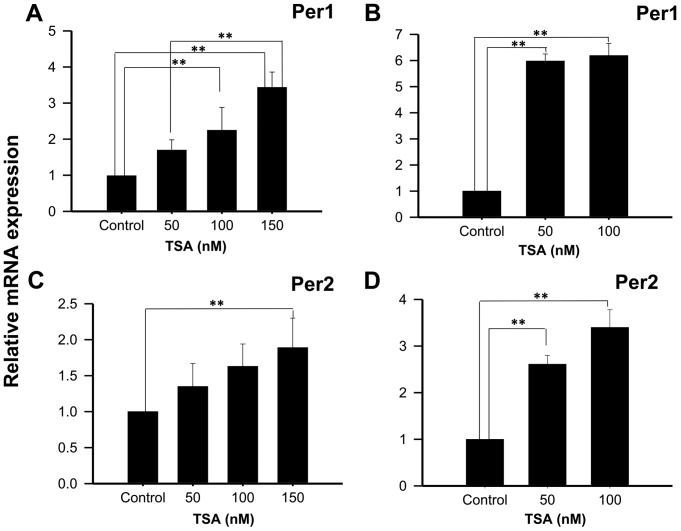

On the other hand, treatment of NCI-N87 cells with 50, 100 or 150 nM TSA for 48 h increases Per1 mRNA expression (1.71±0.27; 2.26±0.62, and 3.45±0.41 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 4A); whereas treatment for 96 h show significant increases at 50 and 100 nM TSA (5.98±0.27 and 6.19±0.47 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 4B). Similar to the results found for Per1, treatment of NCI-N87 cells with 150 nM TSA during 48 h induced Per2 mRNA expression (1.89±0.41 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 4C). This effect was more evident after 96 h of treatment with 50 or 100 nM of TSA (2.61±0.19 and 3.4±0.38 fold higher than control untreated cells, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

TSA induces the mRNA expression of Per1 and Per2 in human NCI-N87 gastric cancer cells. NCI-N87 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TSA for (A and C) 48 or (B and D) 96 h, then Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression was determined by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. **P<0.01, as indicated. Per, period circadian regulator; TSA, Trichostatin A.

Effect of NaB and TSA on histone modifications and Sp1 and Sp3 binding to the Per1 and Per2 promoters

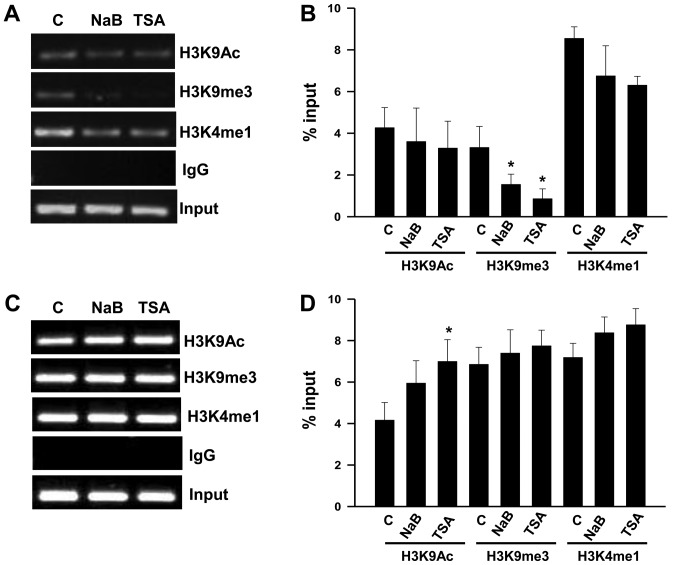

We conducted ChIP assays with KATO III cells to explore changes in histone modifications, in order to understand the mechanism for the upregulation of Per1 and Per2 mRNA by NaB and TSA. We found that treatment with NaB and TSA decreases H3K9me3 (P<0.05) at the Per1 promoter, whereas H3K9Ac and H3K4me1 show no significant changes (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, Per2 promoter shows an increase of H3K9Ac in response to TSA (P<0.05), while H3K9m3 and H3K4me1 did not change compared to untreated cells (Fig. 5C and D). Treatment with NaB does not modify the analyzed chromatin marks at the Per2 promoter (Fig. 5C and D).

Figure 5.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays of Per1 and Per2 promoters of KATO III cells treated with NaB or TSA. Chromatin from KATO III gastric cancer cells treated with 3 mM NaB or 100 nM TSA for 48 h was immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies for H3 modifications. Representative agarose gels (2%) showing polymerase chain reaction products amplified with primers to the (A) proximal promoters of Per1 with (B) quantification, or with primers to the (C) proximal promoter of Per2 with (D) quantification. Gels from three independent ChIP experiments were analyzed with the program ImageJ software version 1.36, and densitometric data for chromatin marks at the Per1 and Per2 promoters are reported in (B) and (D) as mean ± standard deviation, respectively. *P<0.05 vs. C. Per, period circadian regulator; C, untreated control; TSA, Trichostatin A; NaB, sodium butyrate; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

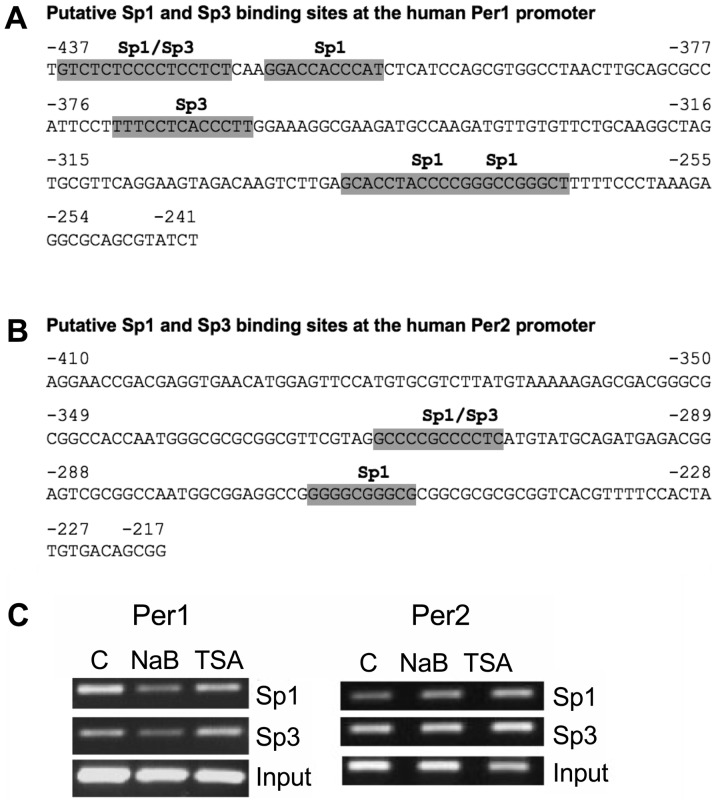

It is known that NaB not only inhibits HDACs, it also acts on non-histone targets, such as transcription factors, in particular, those of the Sp family. Sp1 and Sp3 have been implicated in the mechanism of action of NaB on several promoters (47–51). We then conducted an in silico analysis to search for potential Sp1 and Sp3 binding sites at the Per1 and Per2 promoters. We found four Sp1 and two Sp3 putative binding sites at the −437 to −241 region of the Per1 promoter (Fig. 6A), as well as two Sp1 and one Sp3 putative binding sites at the −410 to −217 region of the Per2 promoter (Fig. 6B). Then we tested for changes of Sp1 and Sp3 binding to these promoters in response to NaB and TSA treatment. ChIP analysis shows that binding of Sp1 and Sp3 decrease at the Per1 promoter in NaB treated cells, whereas TSA has no effect. NaB and TSA treatment increases Sp1 binding to the Per2 promoter, without affecting Sp3 binding (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Binding of Sp1 and Sp3 transcription factors to the Per1 and Per2 promoters of NaB and TSA treated KATO III cells. (A and B) In silico analysis, using the JASPAR database (70), of (A) Per1 and (B) Per2 promoters showing putative Sp1 and Sp3 binding sites. (C) Chromatin from KATO III cells treated with NaB and TSA, as described in Fig. 5, was immunoprecipitated with Sp1 or Sp3 antibodies then was subjected to polymerase chain reaction with primers for Per1 or Per2 promoters, and fragments were separated on 2% agarose gels. Per, period circadian regulator; TSA, Trichostatin A; NaB, sodium butyrate.

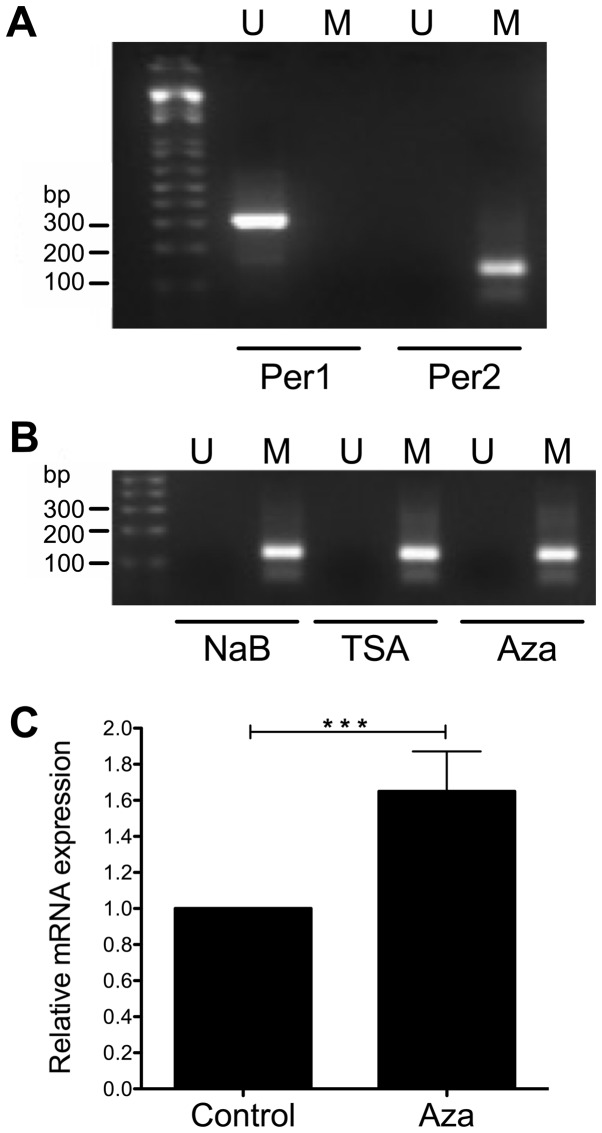

Effect of NaB, TSA, and Aza on the CpG methylation of Per1 and Per2 promoters

To further understand the transcriptional activation of Per1 and Per2 by NaB and TSA we conducted MS-PCR to explore changes on CpG methylation at the promoters of these genes, as HDACi treatment may decrease DNA methylation (52,53). We found that Per1 promoter was not methylated at the CpGs detected by the primers, whereas Per2 promoter was methylated (Fig. 7A). Treatment of KATO III cells with NaB, TSA and even Aza does not change the methylation status of the CpGs analyzed by the primers at the Per2 promoter (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, KATO III cells treated with Aza show a modest but significant increase in Per2 mRNA (1.65±0.22 fold above untreated cells; P<0.001; Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Methylation specific PCR to analyze the methylation status of Per1 and Per2 promoters. KATO III cells were treated with 3 mM NaB, 100 nM TSA for 48 h or 5 mM Aza for 96 h. Then DNA was subjected to bisulfite modification and PCR was conducted with specific primers to distinguish methylated (Lane M) and unmethylated (Lane U) forms of CpGs at the Per1 and Per2 promoters. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels. (A) MS-PCR of untreated control KATO III cells. (B) MS-PCR of NaB, TSA or Aza treated KATO III cells. (C) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR showing upregulation of Per2 mRNA in Aza treated KATO III cells. ***P<0.001, as indicated. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Per, period circadian regulator; NaB, sodium butyrate; TSA, Trichostatin A; MS-PCR, Methylation specific-PCR; Aza, 5-Aza-2′-deoxycitydine.

Discussion

The circadian system may have an important role in the global epigenetic events occurring during carcinogenesis. Accumulating evidence indicates that a variety of chromatin remodelers contribute to various aspects of the circadian epigenome (4,54). This evidence is further supported by gene expression and DNA methylation studies at the promoter region of clock genes silenced in cancer cells (23,27,35,41).

In this study, we found that treatment of KATO III and NCI-N87 human gastric cancer cells with two HDACi (NaB or TSA) induce Per1 and Per2 mRNA expression, in a dose-dependent manner. Our results are consistent with those described by other authors, who used similar treatments to induce the expression of Per1 and Per3 genes in cancer cells. It has been shown that TSA and 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine increased Per3 mRNA expression in myeloid leukemia K562 cells (41). Also, HDAC inhibition by SAHA increased Per1 gene expression in lung cancer NSCLC cells and other cancer cell lines (35). However, the levels of induction obtained in our study were higher than those obtained for Per3 in TSA treated K562 cells (41), but were lower than those obtained with SAHA in H520, H522, Ishikawa, MDA-231, and HCT116 cells, which were more than 10-fold higher than untreated cells (35). This approach has also been used to induce the expression of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in cancer cell lines (55–57).

We also found higher effects of NaB and TSA in cells treated for 96 h than those treated for 48 h, and larger changes of Per1 and Per2 expression were found in KATO III than in NCI-N87 cells. It is well established that gene expression levels in response to HDACi is highly dependent on the cell type (35,45,58). This could explain the differences observed between KATO III and NCI-N87 cells.

Inhibition of HDAC activity may play a key role in the expression of Per1 and Per2 genes in gastric cancer cells by promoting and open chromatin conformation. We found that treatment with NaB and TSA decreases H3K9me3, a heterochromatin mark, at the Per1 promoter, whereas TSA increases H3K9Ac, a mark of euchromatin, at the Per2 promoter, suggesting that these changes may contribute to their transcriptional activation. It is well established that H3K9 methylation correlates with transcriptional repression of multiple genes (59,60).

Enhanced acetylation of H3 and H4 at the Per1 promoter correlate with its transcriptional activation phase in mouse tissues (4,42,61), whereas di- and tri-methylation of H3K27 at the promoters of Per1 and Per2 correlate with transcriptional repression (62). A previous study has also shown that SAHA induced Per1 expression by increasing H3 acetylation at the Per1 promoter of NSLC cells (35). We did not find an increase of H3K9Ac at the Per1 promoter in NaB or TSA treated KATO III cells, but we found a decrease of H3K9 trimethylation. We cannot rule out the possibility that other residues in H3, such as K27, or in H4 could increase their acetylation in response to NaB or TSA.

Our data also demonstrate that NaB induced higher mRNA levels than TSA in both cell lines. NaB not only inhibits HDACs, it also acts on non-histone targets, such as Sp1 and Sp3 transcriptional factors, who have been implicated in the mechanism of action of NaB on several promoters (47–51). Our in silico analysis predicted Sp1 and Sp3 binding sites at the Per1 and Per2 promoters, thus we tested for changes in binding of these factors by ChIP assays. We found decreased Sp1 and Sp3 binding to the Per1 promoter in response to NaB, but not to TSA, whereas Sp1 binding increased at the Per2 promoter in response to NaB and TSA. This suggests that, Sp1 and Sp3 could negatively regulate Per1 expression, while Sp1 recruitment could contribute to the upregulation of Per2 in KATO III cells. Most studies have shown that NaB induce transcriptional activation by enhancing Sp1 and Sp3 binding to gene promoters (47–50); however, others have shown the opposite effect (51). NaB down-regulates neuropilin 1 (NRP1) expression and was associated with decreased binding of Sp1 to the NRP1 promoter (51). On the other hand, Sp1 down-regulates STC1 gene expression in HT-29 cells treated with TSA, by forming a complex with the retinoblastoma protein (63). Sp1 and Sp3 also interact with c-Myc to repress p21 promoter (64). Additionally, Sp1 was able to activate and to repress the thymidine kinase promoter in mouse 3T3 fibroblasts. This ambivalence of Sp1 as a transcriptional modulator lies on the interaction with other proteins, when it interacts with HDAC1 acts as a transcriptional suppressor, whereas when interacts with E2F1-3 promotes transcriptional activation (65). However, further experiments are needed to fully understand the possible role of Sp1 and Sp3 on Per1 transcriptional regulation, mediated by NaB or TSA.

Some studies have shown that HDACi treatment may reverse CpG methylation at gene promoters, leading to transcriptional activation (52,53), thus we tested this possibility. Our results show that Per2 promoter was methylated, whereas Per1 promoter was not methylated. The methylation of the CpGs recognized by the primers at the Per2 promoter did not change in response to NaB or TSA, neither in cells treated with 5-Aza. However, treatment with Aza induced a modest Per2 mRNA expression. It will be necessary to conduct DNA sequencing with bisulfite modified DNA, in order to determine if other CpGs are methylated at the promoter of these genes, and whether NaB, TSA or Aza may modify the pattern.

We cannot rule out the possibility that other mechanisms could indirectly mediate Per1 and Per2 upregulation in response to HDACi. Possibly by inducing transcription factors that bind to regulatory elements, which in turn could activate Per1 or Per2 promoters. Promoter analysis and promoter reporter constructs have shown important transcription factor binding sites that activate Per1 or Per2 expression, like E-boxes, CRE-elements, CAAT-boxes, C/EBP, and others (15,66–68). Acetylation of BMAL1, mediated by the intrinsic HAT activity of CLOCK could be involved in the induction of expression of Per1 and Per2 genes (69,70), by recruiting co-activating proteins such as P300 to the promoters of Per1 and Per2 genes, as previously described (42). However, further experiments are needed to fully understand the transcriptional regulation of these genes in gastric cancer cells.

In conclusion, the results presented in this work demonstrate that inhibition of HDACs with NaB or TSA induce the expression of Per1 and Per2 genes in KATO III and NCI-N87 gastric cancer cells, through changes in chromatin modifications at Per1 and Per2 proximal promoters, as well as changes of Sp3 and/or Sp1 binding to the Per1 and Per2 promoters. Changes in epigenetic modifications of Per1 and Per2 could disrupt other clock genes, as well as a web of genes and cellular pathways under circadian control. Further experiments will be necessary to address these issues. The understanding of changes in the epigenome of cancer cells could contribute to the development of new cancer therapies, and HDACi offer an excellent alternative.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from Programa de Mejoramiento del Profesorado, Secretaría de Educación Pública de México (grant no. PTC-270), Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, México (grant no. 2015-01-1518), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (grant no. IN217216), and FH-R was supported by a scholarship (no. 223273) from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, México.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contribution

FHR performed, analyzed and discussed the majority of the experiments, prepared the figures, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AHO performed the ChIP assays, MS-PCR and in silico analysis, discussed and interpreted the data, and prepared the figures. LFP performed ChIP assays and critically revised the manuscript. GR conducted part of the cell culture work and critically revised the manuscript. MC discussed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. AZH contributed to the study design, acquired funding, discussed and interpreted the data, and critically revised and edited the manuscript. JSG conceived and designed the study, discussed and interpreted the data, acquired funding, and wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Genetics of circadian rhythms in mammalian model organisms. Adv Genet. 2011;74:175–230. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387690-4.00006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partch CL, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buhr ED, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Kramer A, Merrow M, editors. circadian clocks, handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2013;217:3–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koike N, Yoo SH, Huang HC, Kumar V, Lee C, Kim TK, Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture and chromatin landscape of the core circadian clock in mammals. Science. 2012;338:349–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1226339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katada S, Sassone-Corsi P. The histone methyltransferase MLL1 permits the oscillation of circadian gene expression. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1414–1421. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kettner NM, Katchy CA, Fu L. Circadian gene variants in cancer. Ann Med. 2014;46:208–220. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.914808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechtold DA, Gibbs JE, Loudon AS. Circadian dysfunction in disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiessling S, Beaulieu-Laroche L, Blum ID, Landgraf D, Welsh DK, Storch KF, Labrecque N, Cermakian N. Enhancing circadian clock function in cancer cells inhibits tumor growth. BMC Biol. 2017;15:13. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cash E, Sephton SE, Chagpar AB, Spiegel D, Rebholz WN, Zimmaro LA, Tillie JM, Dhabhar FS. Circadian disruption and biomarkers of tumor progression in breast cancer patients awaiting surgery. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;48:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene MW. Circadian rhythms and tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2012;318:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasuniwa Y, Izumi H, Wang KY, Shimajiri S, Sasaguri Y, Kawai K, Kasai H, Shimada T, Miyake K, Kashiwagi E, et al. Circadian disruption accelerates tumor growth and angio/stromagenesis through a Wnt signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dycke KC, Rodenburg W, van Oostrom CT, VanKerkhof LW, Pennings JL, Roenneberg T, van Steeg H, Vanderhorst GT. Chronically alternating light cycles increase breast cancer risk in mice. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1932–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu L, Pelicano H, Liu J, Huang P, Lee C. The circadian gene Period2 plays an important role in tumor suppression and DNA damage response in vivo. Cell. 2002;111:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papagiannakopoulos T, Bauer MR, Davidson SM, Heimann M, Subbaraj L, Bhutkar A, Bartlebaugh J, Vander Heiden MG, Jacks T. Circadian rhythm disruption promotes lung tumorigenesis. Cell Metab. 2016;24:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gery S, Gombart AF, Yi WS, Koeffler C, Hofmann WK, Koeffler HP. Transcription profiling of C/EBP targets identifies Per2 as a gene implicated in myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:2827–2836. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gery S, Komatsu N, Baldjyan L, Yu A, Koo D, Koeffler HP. The circadian gene per1 plays an important role in cell growth and DNA damage control in human cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2006;22:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua H, Wang Y, Wan C, Liu Y, Zhu B, Yang C, Wang X, Wang Z, Cornelissen-Guillaume G, Halberg F. Circadian gene mPer2 overexpression induces cancer cell apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:589–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiang S, Coffelt SB, Mao L, Yuan L, Cheng Q, Hill SM. Period-2: A tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer. J Circadian Rhythms. 2008;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X, Wood PA, Oh EY, Du-Quiton J, Ansell CM, Hrushesky WJ. Down regulation of circadian clock gene Period 2 accelerates breast cancer growth by altering its daily growth rhythm. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:423–431. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyazaki K, Wakabayashi M, Hara Y, Ishida N. Tumor growth suppression in vivo by overexpression of the circadian component, PER2. Genes Cells. 2010;15:351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oda A, Katayose Y, Yabuuchi S, Yamamoto K, Mizuma M, Shirasou S, Onogawa T, Ohtsuka H, Yoshida H, Yoshida H, et al. Clock gene mouse period2 overexpression inhibits growth of human pancreatic cancer cells and has synergistic effect with cisplatin. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1201–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter SL, Bosnoyan-Collins L, Pinnaduwage D, Andrulis IL. Expression of the circadian clock genes Pert and Per2 in sporadic and familial breast tumors. Neoplasia. 2007;9:797–800. doi: 10.1593/neo.07595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen ST, Choo KB, Hou MF, Yeh KT, Kuo SJ, Chang JG. Deregulated expression of the PER1, PER2 and PER3 genes in breast cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1241–1246. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai H, Zhang L, Cao M, Song F, Zheng H, Zhu X, Wei Q, Zhang W, Chen K. The role of polymorphisms in circadian pathway genes in breast tumorigenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:531–540. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao Q, Gery S, Dashti A, Yin D, Zhou Y, Gu J, Koeffler HP. A role for the clock gene per1 in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7619–7625. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokunaga H, Takebayashi Y, Utsunomiya H, Akahira J, Higashimoto M, Mashiko M, Ito K, Niikura H, Takenoshita S, Yaegashi N. Clinicopathological significance of circadian rhythm-related gene expression levels in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:1060–1070. doi: 10.1080/00016340802348286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh KT, Yang MY, Liu TC, Chen JC, Chan WL, Lin SF, Chang JG. Abnormal expression of period 1 (PER1) in endometrial carcinoma. J Pathol. 2005;206:111–120. doi: 10.1002/path.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Relles D, Sendecki J, Chipitsyna G, Hyslop T, Yeo CJ, Arafat HA. Circadian gene expression and clinicopathologic correlates in pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:443–450. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzoccoli G, Panza A, Valvano MR, Palumbo O, Carella M, Pazienza V, Biscaglia G, Tavano F, Di Sebastiano P, Andriulli A, Piepoli A. Clock gene expression levels and relationship with clinical and pathological features in colorectal cancer patients. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28:841–851. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.615182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mostafaie N, Kallay E, Sauerzapf E, Bonner E, Kriwanek S, Cross HS, Huber KR, Krugluger W. Correlated downregulation of estrogen receptor beta and the circadian clock gene Per1 in human colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:642–647. doi: 10.1002/mc.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu ML, Yeh KT, Lin PM, Hsu CM, Hsia HH, Liu YC, Lin HY, Lin SF, Yang MY. Deregulated expression of circadian clock genes in gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao H, Zen ZL, Yang Y, Jin Y, Qiu MZ, Hu XY, Han J, Liu KY, Liao JW, Xu RH, Zou QF. Prognostic relevance of Period1 (Per1) and Period2 (Per2) expression in human gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:619–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin YM, Chang JH, Yeh KT, Yang MY, Liu TC, Lin SF, Su W, Chang JG. Disturbance of circadian gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:925–933. doi: 10.1002/mc.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lengyel Z, Lovig C, Kommedal S, Keszthelyi R, Szekeres G, Battyáni Z, Csernus V, Nagy AD. Altered expression patterns of clock gene mRNAs and clock proteins in human skin tumors. Tumor Biol. 2013;34:811–819. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gery S, Komatsu N, Kawamata N, Miller CW, Desmond J, Virk RK, Marchevsky A, Mckenna R, Taguchi H, Koeffler HP. Epigenetic silencing of the candidate tumor suppressor gene Per1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1399–1404. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang MY, Yang WC, Lin PM, Hsu JF, Hsiao HH, Liu YC, Tsai HJ, Chang CS, Lin SF. Altered expression of circadian clock genes in human chronic myeloid leukemia. J Biol Rhythms. 2011;26:136–148. doi: 10.1177/0748730410395527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu CM, Lin SF, Lu CT, Lin PM, Yang MY. Altered expression of circadian clock genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2012;33:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoennissen NH, Thoennissen GB, Abbassi S, Nabavi-Nouis S, Sauer T, Doan NB, Gery S, Müller-Tidow C, Said JW, Koeffler HP. Transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and critical circadian clock downstream target gene PER2 are highly deregulated in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1577–1585. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.658792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia H, Niu Z, Ma H, Cao SZ, Hao SC, Liu ZT, Wang F. Deregulated expression of the Per1 and Per2 in human gliomas. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:365–370. doi: 10.1017/S031716710001026X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhanfeng N, Yanhui L, Zhou F, Shaocai H, Guangxing L, Hechun X. Circadian genes Per1 and Per2 increase radiosensitivity of glioma in vivo. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9951–9958. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang MY, Chang JG, Lin PM, Tang KP, Chen YH, Lin HY, Liu TC, Hsiao HH, Liu YC, Lin SF. Downregulation of circadian clock genes in chronic myeloid leukemia: alternative methylation pattern of hPER3. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1298–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etchegaray JP, Lee C, Wade PA, Reppert SM. Rhythmic histone acetylation underlies transcription in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 2003;421:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature01314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Deprez RH, Moorman AF. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:62–66. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)01423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Contreras-Leal E, Hernandez-Oliveras A, Flores-Peredo L, Zarain-Herzberg A, Santiago-Garcia J. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote the expression of ATP2A3 gene in breast cancer cell lines. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:1477–1485. doi: 10.1002/mc.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan A, Fornes O, Stigliani A, Gheorghe M, Castro-Mondragon JA, van der Lee R, Bessy A, Chèneby J, Kulkarni SR, Tan G, et al. JASPAR 2018: Update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles and its web framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D260–D266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amin MR, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K, Malakooti J. Involvement of Sp1 and Sp3 in differential regulation of human NHE3 promoter activity by sodium butyrate and IFN-gamma/TNF-alpha. AJP Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G374–G382. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00128.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiela PR, Kuscuoglu N, Midura AJ, Midura-Kiela MT, Larmonier CB, Lipko M, Ghishan FK. Molecular mechanism of rat NHE3 gene promoter regulation by sodium butyrate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C64–C74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00277.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flores-Peredo L, Rodriguez G, Zarain-Herzberg A. Induction of cell differentiation activates transcription of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 3 gene (ATP2A3) in gastric and colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56:735–750. doi: 10.1002/mc.22529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chirakkal H, Leech SH, Brookes KE, Prais AL, Waby JS, Corfe BM. Upregulation of BAK by butyrate in the colon is associated with increased Sp3 binding. Oncogene. 2006;25:7192–7200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu DC, Waby JS, Chirakkal H, Staton CA, Corfe BM. Butyrate suppresses expression of neuropilin I in colorectal cell lines through inhibition of Sp1 transactivation. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:276. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar S, Abujamra AL, Loew JE, Forman LW, Perrine SP, Faller DV. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reverse CpG methylation by regulating DNMT1 through ERK signaling. Anticancer Res. 2011;3:2723–2732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin H, Kim JH, Lee YS, Lee YC. Change in gene expression profiles of secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRPs) by sodium butyrate in gastric cancers: Induction of promoter demethylation and histone modification causing inhibition of Wnt signaling. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1533–1542. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masri S, Sassone-Corsi P. Plasticity and specificity of the circadian epigenome. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1324–1329. doi: 10.1038/nn.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng CF, Zhu XJ, Peng G, Dai DQ. Promoter histone H3 lysine 9 di-methylation is associated with DNA methylation and aberrant expression of p16 in gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:1221–1227. doi: 10.3892/or_00000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen MY, Liao WS, Lu Z, Bornmann WG, Hennessey V, Washington MN, Rosner GL, Yu Y, Ahmed AA, Bast RC., Jr Decitabine and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (saha) inhibit growth of ovarian cancer cell lines and xenografts while inducing expression of imprinted tumor suppressor genes, apoptosis, G2/M arrest and autophagy. Cancer. 2011;117:4424–4438. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vibhakar R, Foltz G, Yoon JG, Field L, Lee H, Ryu GY, Pierson J, Davidson B, Madan A. Dickkopf-1 is an epigenetically silenced candidate tumor suppressor gene in medulloblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:135–144. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang J, Varghese DS, Gillam MC, Peyton M, Modi B, Schiltz RL, Girard L, Martinez ED. Differential response of cancer cells to HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A and depsipeptide. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:116–125. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hublitz P, Albert M, Peters AH. Mechanisms of transcriptional repression by histone lysine methylation. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:335–354. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082717ph. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varier RA, MarcTimmers HT. Histone lysine methylation and demethylation pathways in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1815:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Curtis AM, Seo SB, Westgate EJ, Rudic RD, Smyth EM, Chakravarti D, Fitzgerald GA, McNamara P. Histone acetyltransferase-dependent chromatin remodeling and the vascular clock. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7091–7097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Etchegaray JP, Yang X, DeBruyne JP, Peters AH, Weaver DR, Jenuwein T, Reppert SM. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is required for mammalian circadian clock function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21209–21215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Law AY, Yeung BH, Ching LY, Wong CK. Sp1 is a transcriptional repressor to stanniocalcin-1 expression in TSA-treated human colon cancer cells, HT29. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:2089–2096. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gartel AL, Ye X, Goufman E, Shianov P, Hay N, Najmabandi F, Tyner AL. Myc repress the p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter and interacts with Sp1/Sp3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4510–4515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doetzlhofer A, Rotheneder H, Lagger G, Koranda M, Kurtev V, Brosch G, Wintersberger E, Seiser C. Histone deacetylase 1 can repress transcription by binding to Sp1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5504–5511. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.8.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hida A, Koike N, Hirose M, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Tei H. The human and mouse Period1 genes: five well-conserved E-boxes additively contribute to the enhancement of mPer1 transcription. Genomics. 2000;65:224–233. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taruscio D, Zoraqi GK, Falchi M, Iosi F, Paradisi S, DiFiore B, Lavia P, Falbo V. The human Per1 gene: Genomic organization and promoter analysis of the first human orthologue of the Drosophila period gene. Gene. 2000;253:161–170. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koyanagi S, Hamdan AM, Horiguchi M, Kusunose N, Okamoto A, Matsunaga N, Ohdo S. cAMP-response element (CRE)-mediated transcription by activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) is essential for circadian expression of the Period2 gene. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32416–32423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doi M, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian regulator CLOCK is a histone acetyltransferase. Cell. 2006;125:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grimaldi B, Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Kaluzova M, Gauthier D, Pham K, Patel N, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Chromatin remodeling and circadian control: Master regulator CLOCK is an enzyme. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007;72:105–112. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.