Abstract

Introduction:

Parenteral form of lidocaine is the best-known source of lidocaine poisoning. This study aimed to evaluate the characteristics of acute lidocaine toxicity .

Methods:

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, demographics, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and outcome of patients intoxicated with lidocaine (based on ICD10 codes) admitted to Loghman Hakim Hospital, during April 2007 to March 2014 were analyzed.

Results:

30 cases with the mean age of 21.83 ± 6.57 year were studied (60% male). All subjects had used either 6.5% lidocaine spray or 2% topical formulations of lidocaine. The mean consumed dose of lidocaine was 465 ± 318.17 milligrams. The most frequent clinical presentations were nausea and vomiting (50%), seizure (33.3%), and loss of consciousness (16.7%). 22 (73.3%) cases had normal sinus rhythm, 4 (13.3%) bradycardia, 2 (6.7%) ventricular tachycardia, and 2 (6.7%) had left axis deviation. 11 (36.6%) cases were intubated and admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) for 6.91 ± 7.16 days. Three patients experienced status epilepticus that led to cardiac arrest, and death (all cases with suicidal intention).

Conclusion:

Based on the results of this study, most cases of topical lidocaine toxicity were among < 40-year-old patients with a male to female ratio of 1.2, with suicidal attempt in 90%, need for intensive care in 36.6%, and mortality rate of 10%.

Key Words: Lidocaine, poisoning, drug-related side effects and adverse reactions, administration

Introduction

Lidocaine is an amide-type local anesthetic and a class Ib antidysrhythmic agent, available since 1948. Systemic exposure to large amounts of it leads to adverse effects on the cardiovascular and central nervous systems (CNS). The primary mechanism of action is interrupting cardiac and neural signal conduction by hindering the influx of sodium ions via Na+-channels. Therefore, it can cause increased depolarization threshold and abortive action potential (1, 2). Lidocaine toxicity is dosage-dependent and directly relative to its plasma concentration. Likewise, the possibility of lidocaine toxicity is considered to be clinically significant at plasma concentrations higher than 6.0 mg/L (3-7).

Diagnosis is done based on clinical presentation, blood levels of lidocaine and imaging studies. Anaphylaxis, anxiety disorders, cocaine toxicity, and conversion disorders should be considered in differential diagnosis of patients. The leading complications of lidocaine toxicity are cardiac arrest, local ischemia or nerve toxicities. Management of lidocaine toxicity comes when airway compromises, and substantial hypotension, dysrhythmias, and seizures take place (8-10).

Parenteral form of lidocaine is the best-known source of poisoning, but poisoning could also happen with topical spray formulation (11).

Despite the importance of lidocaine toxicity, there is a scarcity of studies in this regard. The existing researches are limited to either intravenous or oral poisoning. Here, we present clinical presentation, management, and outcome of acute poisoning cases with topical gel and spray forms of lidocaine.

Methods

Study design and setting

In this retrospective cross-sectional study demographics, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, management, and outcome of lidocaine intoxicated patients (based on ICD10 definitions) admitted to Loghman Hakim Hospital, from April 2007 to March 2014 were analyzed. This center is a unique referral poisoning center placed in the capital of Iran, Tehran. The study protocol was approved by ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and researchers adhered to principles of Helsinki recommendations.

Participants

All cases who met the ICD10 codes of lidocaine toxicity who were referred to the emergency department (ED) of the mentioned hospital during the study period were evaluated without any sex or age limitation. Patients with incomplete records, multidrug toxicity, and any history of seizure were excluded.

Data gathering

Using documented patient profiles, a checklist containing demographics, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and the outcome was filled out for all included patients by a senior toxicology resident. We converted the percentage amount of lidocaine per dose to milligrams in order to better report the results. Intensive care unit (ICU) admission indications were considered as loss of consciousness, seizures, cardiac dysrhythmias, and intubation.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) and p-value under 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous data were examined by student t-test if the data were normally distributed (indicated by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test); otherwise, Mann–Whitney U-test was applied. Categorical data were compared using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Baseline demographics and screening measure variables were compared across groups using chi-square for categorical variables and one-factor (treatment) ANOVA for continuous variables.

Results

Baseline characteristics

30 cases of Lidocaine poisoning with the mean age of 21.83 ± 6.57 (10-40) years were admitted to ED during the study period (60% male). 18 (60%) cases were in 21-30 years age group, 11 (36.7%) were in 10-20 years group, and 1 (3.3%) was in 31-40 years age group. All subjects had used either 6.5% lidocaine spray or 2% topical formulations of lidocaine.

The most prevalent cause of poisoning was suicide attempt (87.5%). The mean consumed dose of lidocaine was 465 ± 318.17 milligrams (11 cases < 500 milligrams and 19 cases ≥ 500 milligrams). The average elapsed time between exposure and admission to the emergency room was 5.1(1 – 76) hours.

Clinical and para-clinical manifestations

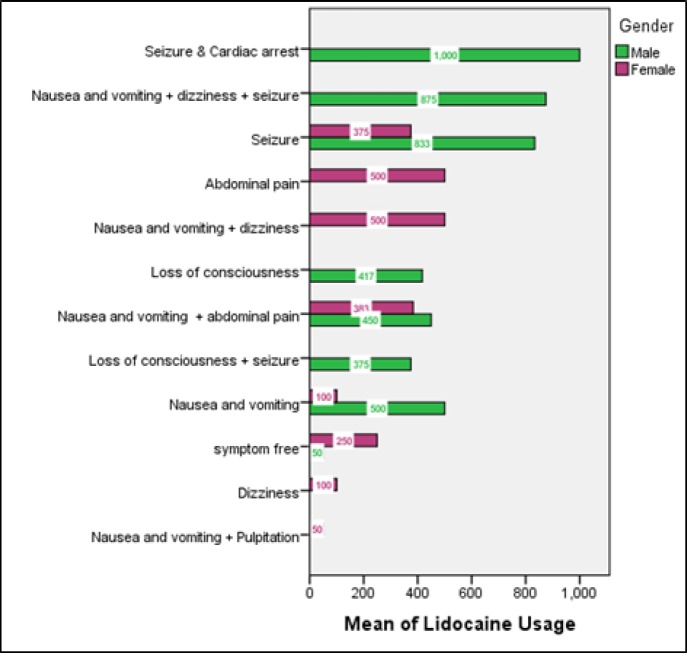

Figure 1 shows the clinical symptoms of patients on admission based on sex and amount of lidocaine consumption. The most frequent clinical presentations were nausea and vomiting (50%), seizure (33.3%), and loss of consciousness (16.7%). Metabolic acidosis was seen in blood gas analysis of all cases and 13 (43.3%) cases presented with some grades of loss of consciousness. Table 1 summarizes clinical and laboratory findings of studied patients based on their intention.

Figure 1.

Clinical symptoms of patients on admission based on the consumed amount of lidocaine and their sex

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory findings of intubated patients based on their intention

| Parameter | Accidental (n=3) | Suicidal (n=27) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 106.67 ± 23.62 | 109.37 ± 21.88 | 0.948 |

| Diastolic blood pressure(mm Hg) | 72.50 ± 3.53 | 70.04 ± 12.68 | 0.523 |

| Pulse rate (Beats/minute) | 84.00 ± 10.58 | 84.30 ± 24.24 | 0.845 |

| Respiratory rate (Beats/minute) | 15.00 ± 4.24 | 17.54 ± 9.48 | <0.001 |

| Presentation | |||

| Loss of consciousness (Reed Scale) | 2.67 ± 2.30 | 1.33 ± 1.79 | 0.424 |

| Seizure | 1 (3.3) | 9 (30) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic acidosis | 0 (0) | 8 (26.6) | 0.197 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Lidocaine amount (milligrams)* | 666.67 ± 288.67 | 442.59 ± 318.26 | 0.200 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (U/L) | 18.33 ± .57 | 36.04 ± 49.77 | 0.524 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (U/L) | 13.00 ± 4.58 | 29.64 ± 41.72 | 0.391 |

| Total Serum Bilirubin (mg/dL) | .53 ± .25 | .58 ± .45 | 0.543 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.70 ± 1.47 | .96 ± .24 | 0.016 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140.33 ± 2.30 | 142.19 ± 3.67 | 0.300 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.73 ± .25 | 4.192± .72 | 0.130 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 22.50 ± 3.06 | 24.21 ± 6.75 | 0.475 |

| Serum Glucose (mg/dL) | 131 ± 45.39 | 119.81 ± 58.11 | 0.389 |

| Serum BUN (mg/dL) | 20.33 ± 3.78 | 24.88 ± 7.58 | 0.196 |

based on reports from patients or their companions. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

22 (73.3%) cases had normal sinus rhythm, 4 had (13.3%) bradycardia, 2 (6.7%) had ventricular tachycardia, and 2 (6.7%) had left axis deviation on electrocardiography (ECG).

Brain computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in three patients, which revealed hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cortical atrophy.

Management and outcome

18 (60%) patients were treated with supportive care such as intravenous fluid and anti-epileptic agents. 11 (36.6%) cases were intubated and admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) for 6.91 ± 7.16 (1-24) days.

Three patients experienced status epilepticus that led to cardiac arrest, and death (100% with sucidal intention). Mortality rate was 10%, and those who were discharged gained full recovery. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the three deceased individuals.

Table 2.

Complete characteristics of deceased cases of lidocaine poisoning

| Variable | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (year) | 20 | 21 | 27 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male |

| Vital signs | |||

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 170/80 | 70/50 | 100/70 |

| Pulse rate (/minutes) | 100 | 72 | 109 |

| Respiratory rate (/minutes) | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Paraclinical findings | |||

| Lidocaine amount (mg) | 250 | 250 | 1000 |

| Conscioussness | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| ICU stay (days) | 15 | 2 | 3 |

| Metabolic acidosis | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Brain CT findings | |||

| Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy | Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy | - | |

| Electrocardiographic finding | |||

| Ventricular tachycardia | Left axis deviation | Bradycardia | |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Stable Convulsions, Reduced consciousness, Cardiac arrest |

Generalized-tonic-clonic seizures, Decreased consciousness, Ventricular tachycardia, Cardiac arrest |

Stable convulsions, Reduced consciousness, Sinus bradycardia, Cardiac arrest |

|

Discussion

Based on the results of this study, most cases of topical lidocaine toxicity were among < 40-year-old patients with male to female ratio of 1.2, with a sucidal attempt in 90%, need for intensive care in 36.6%, and mortality rate of 10%.

Previous investigations demonstrated parenteral formulations of lidocaine as a source of accidental and intentional poisoning (12-19). In the United States in 2015, 1334 single exposures to lidocaine were reported (20).

Although in many case studies lidocaine toxicity has been reported to happen inadvertently, we found 27 cases (90%) of intentional ingestion in six years. To date, there is one case report with two fatal subjects of deliberate consumption (13).

Most of the studies indicated that following lidocaine use, only 35% of the consumed lidocaine reaches the systemic circulation and 65% of it is rapidly absorbed and digested by the liver hepatocytes. Full elimination of lidocaine occurs with a half-life of 0.7-1.8 hours, and 3% of lidocaine is discharged unchanged in the 24-hour urine (21-23). Nevertheless, the peak clinical signs and symptoms of lidocaine toxicity are observed 10-25 minutes after ingestion (12, 24, 25). The critical fact is that distribution kinetics are not so imperative in understanding the course of effects or toxicity of lidocaine when it is used for local anesthesia or after oral ingestion (26).

There is no specific treatment for lidocaine toxicity. Here, the majority of cases received supportive care (60%). Thus, management is symptomatic to prevent hypoxia, acidosis, and hyperkalemia, which may increase the risk of cardiac toxicity. Gastric decontamination is of partial value due to the quick absorption after ingestion. Benzodiazepine and barbiturates can be prescribed to control local anesthetic-induced seizure. Still, they may aggravate circulatory and respiratory depression. Likewise, propofol has been used effectively to end the seizure in subjects with lidocaine toxicity(27, 28).

Studies proved that toxicity would increase by acidosis (29) and decreased by alkalosis (30). The majority of manifestations in this study owed to neurotoxicity of lidocaine that has been reported by other investigations as well (15, 31). The clinical symptoms after consumption of approximately two to more than 24 mg/ml of lidocaine are tongue numbness, dizziness, auditory and visual disorders, loss of consciousness, seizures, coma, and respiratory and cardiac arrest. Eventually, in this study, three people underwent cardiac arrest all of whom had previous experiences of neurological symptoms including decreased level of consciousness and seizures.

In this research, mortality rate was 10 %. So far, in most of the studies, fatal cases of lidocaine toxicity were reported, either accidental or intentional. The considerable point here is that systemic toxicity of lidocaine can be life-threatening. Hence, the rapid evaluation of clinical manifestations is essential to prevent mortality.

In the current study, the mean consumed dosage of lidocaine was 465 ± 318.17 mg/ml. This study was performed retrospectively; therefore, we could not find any evidence of lidocaine assessment in the plasma samples. In general, lidocaine is dose-related, and toxicity may emerge at 8 mg/L or higher serum concentrations. Researchers revealed that lidocaine toxicity could manifest by using high dosages of this remedy and system hypersensitivity in individuals (21).

In this study, a significant portion of patients were male (60%), and the most frequent age range was 21-30 years. In one CDC survey between 1981-1983, 43,813 out of 51,880 workers with lidocaine toxicity were female (32). Following reviewing all studies on “lidocaine poisoning/intoxication” in PubMed and Google Scholar databases, we found seven parallel studies. Five of the cases occurred in women, three in men and one did not mention. The mean age of the victims was 47.25 years (12, 16, 33-37), which is higher than our results. The difference may be because of accidental poisoning in the elderly.

This case series illustrated the relatively high suicidal rate in lidocaine poisoning and focuses on the management of such patients. Clinicians need to be aware of the possible toxicity of topical or oral lidocaine and wisely review dosage schedules and discuss potential toxicity with patients in addition to allowing for alternative therapeutic modalities.

Limitations

Since this was a retrospective study, the primary limitation was that the ingested dose of lidocaine was determined by taking a history of the patients and some patients may not have declared the exact dosage. Besides, lidocaine blood level could not be evaluated because we do not have the equipment in Iran. Therefore, serum lidocaine concentrations must be determined in further studies.

Conclusion:

Based on the results of this study, most cases of topical lidocaine toxicity were among < 40 year old patients with a male to female ratio of 1.2, with suicidal attempt in 90%, need for intensive care in 36.6%, and mortality rate of 10%.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express gratitude to the staff of Loghman Hakim Hospital who supported us in conducting this study.

Author contributions:

This paper was based on Dr. Elmi’s thesis. Dr. Rahimi and Dr. Shadnia were the supervisor and advisor professors, respectively. They conceived the presented idea. Dr. Elmi gathered the data and performed the primary statistical analysis. Dr. Soltaninejad and Dr. Forouzanfar revised the primary form of the article. Dr.Hassanian-Moghaddam and Dr. Zamani revised the final version of the study. All authors discussed the results, took part in preparing the final manuscript and agreed upon the concluding version of the document.

Funding/support:

We received no funding or support for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.McBride ME, Marino BS, Webster G, Lopez-Herce J, Ziegler CP, De Caen AR, et al. Amiodarone versus lidocaine for pediatric cardiac arrest due to ventricular arrhythmias: a systematic review. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2017;18(2):183–9. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ugur B, Ogurlu M, Gezer E, Aydin ON, Gürsoy F. Effects of Esmolol, Lidocaine and Fentanyl on haemodynamic responses to endotracheal intubation. Clinical drug investigation. 2007;27(4):269–77. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200727040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butterworth JF, Strichartz GR. Molecular mechanisms of local anesthesia: a review. Anesthesiology. 1990;72(4):711–34. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199004000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barash M, Reich KA, Rademaker D. Lidocaine-Induced Methemoglobinemia: A Clinical Reminder. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2015;115(2):94–8. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2015.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran AN, Koo JY. Risk of systemic toxicity with topical lidocaine/prilocaine: a review. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD. 2014;13(9):1118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayas M, Işık B. Does Low Dose Lidocaine Cause Convulsions? Turkish journal of anaesthesiology and reanimation. 2014;42(2):106. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2014.21043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akrami M, Akhavizadegan H, Afsari F. Tonic clonic convulsions induced by low dose intrathecal bupivacaine and intraurethral lidocaine gel. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care. 2016;20(3):358–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neal J, Mulroy M, Weinberg G. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine checklist for managing local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37(1):16–8. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31822e0d8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekimoto K, Tobe M, Saito S. Local anesthetic toxicity: acute and chronic management. Acute Medicine & Surgery. 2017 doi: 10.1002/ams2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soltesz EG, van Pelt F, Byrne JG. Emergent cardiopulmonary bypass for bupivacaine cardiotoxicity. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2003;17(3):357–8. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(03)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Soltaninejad K, Ghoochani A, Mohebpour V-R, Shadnia S. The Report of Suicide by Ingestion of Lidocaine Topical Spray. Iranian Journal of Toxicology. 2014;8(24):1034–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centini F, Fiore C, Riezzo I, Rossi G, Fineschi V. Suicide due to oral ingestion of lidocaine: a case report and review of the literature. Forensic science international. 2007;171(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawling S, Flanagan R, Widdop B. Fatal lignocaine poisoning: report of two cases and review of the literature. Human toxicology. 1989;8(5):389–92. doi: 10.1177/096032718900800512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalin JR, Brissie RM. A case of homicide by lethal injection with lidocaine. Journal of Forensic Science. 2002;47(5):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KUDO K, NISHIDA N, KIYOSHIMA A, IKEDA N. A Fatal Case of Poisoning by Lidocaine Overdosage–Analysis of Lidocaine in Formalin-Fixed Tissues. Medicine, science and the law. 2004;44(3):266–71. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.44.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S-K, Lee S-Y, In S-W, Choi H-K, Lim M-A, Chung K-H, et al. Lidocaine intoxication: two fatal cases. Archives of pharmacal research. 2003;26(4):317–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02976962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Lee F, Lau F. A lady with confusion and seizure after ingestion of lidocaine for dyspepsia. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2009;16:41–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poklis A, Mackell MA, Tucker E. Tissue distribution of lidocaine after fatal accidental injection. Journal of Forensic Science. 1984;29(4):1229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu K, Shiono H, Matsubara K, Awaya T, Takahashi T, Saito O, et al. The tissue distribution of lidocaine in acute death due to overdosing. Legal Medicine. 2000;2(2):101–5. doi: 10.1016/s1344-6223(00)80032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, Zimmerman A, Schauben JL. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa) 2016;54(10):924–1109. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2016.1245421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baselt RC. Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man. Chemical Toxicology Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benowitz NL, Meister W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lignocaine. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 1978;3(3):177–201. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197803030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denaro CP, Benowitz NL. Poisoning Due to Class 1B Antiarrhythmic Drugs. Medical toxicology and adverse drug experience. 1989;4(6):412–28. doi: 10.1007/BF03259923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donald M, Derbyshire S. Lignocaine toxicity; a complication of local anaesthesia administered in the community. Emergency medicine journal. 2004;21(2):249–50. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.008730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajimaghsoudi M, Zeinali F, Mansory M, Seyedhosseini J. Seizure Following Lidocaine Administration during Rapid Sequence Intubation; a Case Report. Iranian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;4(2):79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shannon MW, Borron SW, Burns M. Haddad and Winchester's clinical management of poisoning and drug overdose. System. 2007;133:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heavner J, Arthur J, Zou J, McDaniel K, Tyman-Szram B, Rosenberg P. Comparison of propofol with thiopentone for treatment of bupivacaine-induced seizures in rats. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1993;71(5):715–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohmura S, Ohta T, Yamamoto K, Kobayashi T. A comparison of the effects of propofol and sevoflurane on the systemic toxicity of intravenous bupivacaine in rats. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1999;88(1):155–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199901000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edgren E, Tilelli J, Gehrz R. Intravencus Lidocaine Overdosage in a Child. Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology. 1986;24(1):51–8. doi: 10.3109/15563658608990445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jong RH, Wagman IH, Prince DA. Effect of carbon dioxide on the cortical seizure threshold to lidocaine. Experimental neurology. 1967;17(2):221–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(67)90147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giordano D, Panini A, Pernice C, Raso MG, Barbieri V. Neurologic toxicity of lidocaine during awake intubation in a patient with tongue base abscess Case report. American journal of otolaryngology. 2014;35(1):62–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sieber W. National occupational exposure survey; sampling methodology. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takinami Y. Case of serious lidocaine intoxication. Masui The Japanese journal of anesthesiology. 2008;57(4):460–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tei Y, Morita T, Shishido H, Inoue S. Lidocaine intoxication at very small doses in terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2005;30(1):6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiang Y, Tseng K, Lih Y, Tsai T, Liu C, Leung H. Lidocaine-induced CNS toxicity--a case report. Acta anaesthesiologica Sinica. 1996;34(4):243–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin S, Wang S, Tso H, Hsieh Y, Shiao C, Young T. A case report of possible lidocaine intoxication due to sprays of 8% lidocaine. Acta anaesthesiologica Sinica. 1994;32(3):219–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lie RL, Vermeer BJ, Edelbroek PM. Severe lidocaine intoxication by cutaneous absorption. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990;23(5):1026–8. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70329-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]