Abstract

Objectives

To compare long-term outcomes of men with adverse pathologic features after adjuvant radiation therapy (ART) versus salvage radiation therapy (SRT) after radical prostatectomy at our institution.

Methods

Patients treated with postprostatectomy radiation therapy with pT3 tumors, or pT2 with positive surgical margins, were identified. Cumulative freedom from biochemical failure (FFBF), freedom from metastatic failure (FFMF), and overall survival rates were estimated utilizing the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate analyses were performed to determine independent prognostic factors correlated with study endpoints. Propensity score analyses were performed to adjust for confounding because of nonrandom treatment allocation.

Results

A total of 186 patients with adverse pathologic features treated with ART or SRT were identified. The median follow-up time after radical prostatectomy was 103 and 88 months after completion of radiation therapy. The Kaplan-Meier estimates for 10-year FFBF was 73% and 41% after ART and SRT, respectively (log-rank, P = 0.0001). Ten-year FFMF was higher for patients who received ART versus SRT (98.6% vs. 80.9%, P = 0.0028). On multivariate analyses there was no significant difference with respect to treatment group in terms of FFBF, FFMF, and overall survival after adjusting for propensity score.

Conclusions

Although unadjusted analyses showed improved FFBF with ART, the propensity score-adjusted analyses demonstrated that long-term outcomes of patients treated with ART and SRT do not differ significantly. These results, with decreased effect size of ART after adjusting for propensity score, demonstrate the potential impact of confounding on observational research.

Keywords: prostate cancer, postprostatectomy radiation, salvage radiation, adjuvant radiation

Nearly 50% of men with prostate cancer will opt for primary treatment with a radical prostatectomy (RP). Although the majority of men undergoing RP are cured, a subset of men with adverse pathologic features (APFs) present at the time of RP will be at an increased risk for developing a biochemical recurrence in the future. APFs that have been significantly correlated with an increased risk for disease recurrence include: extracapsular extension (ECE), seminal vesicle invasion (SVI), and positive surgical margin(s) (PSM).1 Other adverse prognostic factors include: Gleason Score (GS) ≥7 and an elevated preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level.2 For such patients, the 5-year rates of biochemical failure have been estimated to be as high as 40% to 60%.3

Three randomized controlled clinical trials have uniformly demonstrated a biochemical progression-free survival advantage for men with APFs treated with immediate adjuvant radiation therapy (ART) directed at the prostatic fossa versus initial observation.4–6 One trial, Southwest Oncology Group 8794, demonstrated advantages in distant metastasis-free survival and overall survival (OS) with ART compared with observation, with a median follow-up of 12.5 years.5

Despite these findings, it is currently estimated that <20% of men with APFs actually receive ART.7 Some physicians instead offer observation with serial PSA testing to the patients, followed by salvage radiation therapy (SRT) at the time of a biochemical recurrence.1 Although this approach may spare patients who will never develop recurrence of the morbidity associated with prostatic fossa irradiation, there is no level I evidence to support it.

Phase III trials are currently underway to compare ART and early SRT, but results from these trials are not expected for several years. In the meantime, there is no consensus on the optimal postoperative management for men with APFs.1

In the absence of level I evidence to provide an insight into the controversy regarding ART versus selective SRT for patients with APFs, there is a need for comparative studies examining the 2 treatment approaches in cohorts with long-term follow-up data. We therefore performed a single-institution retrospective analysis to compare the long-term outcomes of men with APFs treated with either ART or SRT. We adjusted for potential confounding in the selection of subjects for ART versus SRT by applying propensity score methods during statistical analysis.8

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Collection

After obtaining the approval of institutional research board, patients treated with postprostatectomy radiation therapy (RT) at our institution from 1990 to 2009 were identified, comprising a total of 250 patients. Patients with no APFs at diagnosis (n = 24), no pathology records from time of RP (n = 3), and patients with < 2 years follow-up (n = 36) were excluded from the study. All patients were status-post a radical retropubic prostatectomy (RP) or robotic RP and ilioobturator lymphadenopathy. Only patients with a pT3-4N0 PC or pT2 with PSM were included in this study.

Patient records were reviewed, including the pre-prostatectomy and postprostatectomy pathology and radiology reports, clinic notes, and laboratory data including serum PSA levels before treatment and at each follow-up. Presence of ECE, SVI, and/or PSM, and pre-RP GS and post-RP GS were extracted from pathology reports. Radiation records were also reviewed to determine RT dose, RT field (prostatic fossa alone or prostatic fossa + pelvis), RT technique, time interval between initiation of RT, and date of RP. Patients treated with RT with an undetectable PSA at the time of treatment were classified as receiving ART. All other patients were classified as receiving SRT. When necessary, dates of death were extracted from the Social Security Database as of July 30, 2011.

Radiation Treatment

Before 2009, postprostatectomy RT was delivered by a 4–6-field technique using 18 to 25 MV photons. RT dose to normal adjacent tissues was minimized using custom blocking. The clinical target volume was delineated to include the prostatic/seminal vesicle bed and surrounding periprostatic tissue. Beginning in 2009, a large percentage of patients were treated using intensity-modulated RT.

Irradiation of the pelvic lymph nodes was performed at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. The median RT dose for patients was 66.6 Gy (range, 45.0 to 70.2 Gy), delivered in 1.8 to 2 Gy fractions.

Follow-Up

All patients were seen in follow-up 4 to 6 weeks after completing RT and at 3- to 6-month intervals afterward for the first 2 years after treatment. Afterward, patients were followed at least once annually. Follow-up visits consisted of a history and physical examinations and a serum PSA level. Patients with a rising serum PSA level had further evaluation for recurrent disease, including a digital rectal exam, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, and a radionuclide bone scan.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 11.1 (StataCorp., LP, College Station, TX). The χ2 tests were used to assess associations of categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using 2-sample t tests. The endpoints evaluated were freedom from biochemical failure (FFBF), freedom from metastatic failure (FFMF), and OS, all defined from the date of RT completion. For men with an undetectable PSA before RT, a biochemical failure was defined as a PSA value of ≥0.4 ng/mL with a subsequent confirmation. For all other patients, biochemical failure was defined as 3 documented increases in serum PSA measured at least 6 weeks apart or PSA rise warranting androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Metastatic failure was defined as evidence of regional or distant metastasis on imaging studies, as documented in clinical notes and imaging reports. Cumulative FFBF, FFMF, and OS rates (from time of RT completion) were estimated utilizing the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method. A multivariate analysis (MVA) was performed using Cox proportional hazard modeling to determine independent prognostic factors significantly associated with FFBF, FFMF, and OS. Factors included in the MVA were: treatment group (ART vs. SRT), SVI (positive vs. negative), ECE (positive vs. negative), margin status (positive vs. negative), GS (≤6, 7, 8 to 10), ADT (taken vs. not taken), RT field (prostatic fossa ± pelvis), and age. In addition, time from RP to RT was included in the MVA models to adjust for varying time between surgery and RT between the 2 groups. An alternative survival analysis approach, incorporating a time-dependent covariate for time from diagnosis to RT was completed, with no measurable change in results. Details are available from the corresponding author, upon request. Assumptions of Cox proportional hazards models were verified using the Schoenfeld Residual Method.

A propensity score was calculated to adjust for potential bias because of nonrandom treatment allocation.8 All MVA Cox analyses were performed for the entire patient cohort, both with and without stratification by propensity score quintiles. Covariates included in the propensity score model included: age, race, year of diagnosis, RP GS, ECE, SVI, and surgical margin status. All P-values were 2-sided and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 186 patients with a minimum follow-up of 2 years and known information about at least 1 APF were identified. The median follow-up time from the time of RP was 103 months (range, 30 to 247 mo) and 88 months (range, 25 to 229 mo) from the time of RT completion. The median age of patients was 62 years (range, 42 to 72 y). In total, 40% (n = 74) were treated with ART and 60% (n = 122) received SRT. Patient-related, treatment-related, and tumor-related characteristics, stratified by treatment group, are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences between treatment groups in terms of tumor and treatment characteristics, with the exception of pre-RT PSA (P < 0.01), age at RT (P < 0.01), and time interval between RP initiation of RT for ART versus SRT (P < 0.01).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variables | n (%)

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | SRT | ART | ||

| Age (y) | < 0.01 | |||

| Median | 62 | 63 | 59 | |

| Race | 0.54 | |||

| White | 160 (86.0) | 94 (83.9) | 66 (89.2) | |

| Black | 21 (11.3) | 15 (13.4) | 6 (8.1) | |

| Other | 5 (2.7) | 3 (2.7) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Preradiation PSA (ng/mL) | < 0.01 | |||

| Median | 0.2 | 0.6 | < 0.1 | |

| ECE | 0.45 | |||

| No | 38 (20.4) | 25 (22.3) | 13 (17.6) | |

| Yes | 143 (76.9) | 83 (74.1) | 60 (81.1) | |

| Unknown | 5 (2.7) | 4 (3.6) | 1 (1.4) | |

| SVI | 0.91 | |||

| No | 125 (67.2) | 76 (67.2) | 49 (66.2) | |

| Yes | 57 (30.6) | 34 (30.4) | 23 (31.1) | |

| Unknown | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Margin | 0.45 | |||

| Negative | 38 (20.4) | 24 (21.4) | 14 (18.9) | |

| Positive | 146 (78.5) | 86 (76.8) | 60 (81.1) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Dose | 0.06 | |||

| Median | 66.6 | 66.6 | 66 | |

| Gleason | 0.53 | |||

| ≤6 | 34 (18.3) | 22 (19.6) | 12 (16.2) | |

| 7 | 89 (47.8) | 49 (43.8) | 40 (54.0) | |

| 8–10 | 52 (28.0) | 33 (29.5) | 19 (25.7) | |

| Unknown | 11 (5.9) | 8 (7.1) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Interval from RP to RT (mo) | < 0.01 | |||

| Median | 4.7 | 7.1 | 3.9 | |

| ADT | 0.06 | |||

| No | 145 (78.0) | 82 (73.2) | 63 (85.1) | |

| Yes | 41 (22.0) | 30 (26.8) | 11 (14.9) | |

| Pelvis | 0.40 | |||

| No | 145 (78.0) | 85 (75.9) | 60 (81.1) | |

| Yes | 41 (22.0) | 27 (24.1) | 14 (18.9) | |

| Samarium | 0.25 | |||

| No | 184 (98.9) | 110 (98.2) | 74 (100) | |

| Yes | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | |

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; ART, adjuvant radiation therapy; ECE, extracapsular extension; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy; SRT, salvage radiation therapy; SVI, seminal vesicle invasion.

FFBF

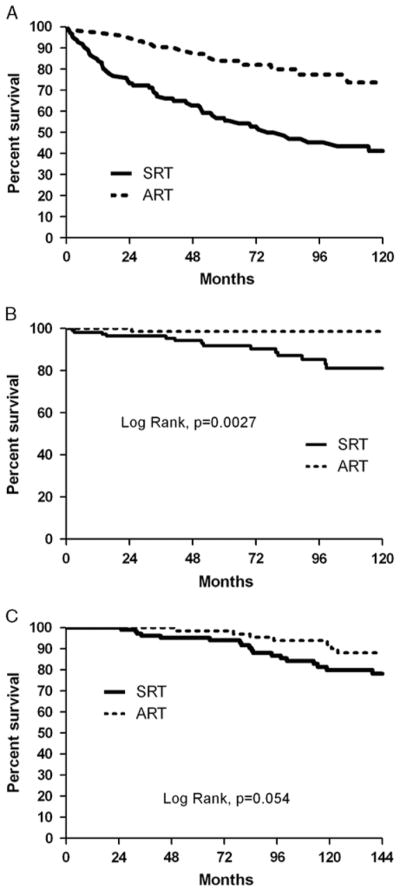

Treatment group was found to significantly affect FFBF (log-rank, P = 0.0001). Estimated 5- and 10-year FFBF rates were 84% and 73%, respectively, for patients treated with ART, and 55% and 41%, respectively, for patients treated with SRT (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

The Kaplan-Meier curves of patients (entire patient cohort) stratified by adjuvant radiation therapy and salvage radiation therapy for (A) freedom from biochemical failure; (B) freedom from metastatic failure; and (C) overall survival.

On MVA performed without adjusting for propensity score, ART was found to be significantly correlated with improved FFBF (hazard ratio [HR], 0.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.21–0.71; P < 0.0001). Presence of SVI on post-RP pathology was associated with decreased FFBF (HR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.35–4.28; P <0.0001). However, after propensity score was incorporated into the MVA model, there was only a trend toward improved FFBF for patients treated with ART (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.26–1.02; P = 0.06). The negative prognostic significance of SVI on postoperative pathology remained significant (HR, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.85–5.73; P < 0.0001). Results of the MVA of FFBF, with and without propensity score adjustment, are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Freedom From Biochemical Failure

| Variables | Unadjusted for Propensity Score

|

Adjusted for Propensity Score

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Treatment | < 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||

| SRT | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| ART | 0.38 | 0.21, 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.26, 1.02 | ||

| Time from RP to RT | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.61 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.46 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 2.40 | 1.35, 4.28 | 3.26 | 1.85, 5.73 | ||

| Extracapsular extension | 0.43 | 0.27 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 1.35 | 0.64, 2.85 | 1.49 | 0.73, 3.02 | ||

| Positive margin | 0.58 | 0.37 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 1.23 | 0.59, 2.55 | 1.37 | 0.69, 2.70 | ||

| Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤6 | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| 7 | 0.97 | 0.43, 2.18 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.39, 1.85 | 0.69 |

| 8–10 | 1.69 | 0.72, 3.95 | 0.23 | 1.28 | 0.56, 2.93 | 0.56 |

| Treatment field | 0.55 | 0.34 | ||||

| Prostatic Fossa | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Prostatic fossa + pelvis | 0.83 | 0.45, 1.53 | 0.74 | 0.4, 1.36 | ||

| ADT | 0.43 | 0.05 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 1.31 | 0.67, 2.56 | 1.93 | 1.0, 3.7 | 0.05 | |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.04 | 0.66 | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.01 | 0.13 |

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; ART, adjuvant radiation therapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy; SRT, salvage radiation therapy.

FFMF

FFMF was also found to be univariably significantly associated with treatment group (log-rank, P = 0.0028). The KM estimates for FFMF at 5 and 10 years were 98.6% (at both time points) for patients treated with ART, and 91.7% and 80.9%, respectively, for patients treated with SRT.

On MVA performed without propensity score adjustment, there was a trend toward improved FFMF for patients treated with ART versus SRT (HR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.01–1.34; P = 0.08). No other variables, including presence of SVI, were found to be significantly associated with FFMF. Similar results were noted after incorporating adjustments for propensity score into Cox proportional hazards modeling. Results of the MVA of FFMF are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Freedom From Metastatic Failure

| Variables | Unadjusted for Propensity Score

|

Adjusted for Propensity Score

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Treatment | 0.08 | 0.10 | ||||

| SRT | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| ART | 0.11 | 0.01, 1.34 | 0.15 | 0.02, 1.38 | ||

| Time from RP to RT | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.03 | 0.49 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 0.29 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | 0.34 | 0.22 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 1.95 | 0.50, 7.62 | 2.20 | 0.63, 7.70 | ||

| Extracapsular extension | 0.92 | 0.74 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.22, 5.35 | 1.31 | 0.27, 6.37 | ||

| Positive margin | 0.21 | 0.17 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 4.20 | 0.44, 40.46 | 5.10 | 0.51, 51.25 | ||

| Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤6 | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| 7 | 0.84 | 0.15, 4.77 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.19, 5.06 | 0.99 |

| 8–10 | 2.42 | 0.38, 15.39 | 0.35 | 1.82 | 0.30, 11.02 | 0.52 |

| Treatment field | 0.54 | 0.7 | ||||

| Prostatic fossa | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Prostatic fossa + pelvis | 1.42 | 0.47, 4.31 | 1.25 | 0.41, 3.76 | ||

| ADT | 0.53 | 0.1 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference group | 1.00 | Reference group | ||

| Yes | 1.69 | 0.34, 8.46 | 3.01 | 0.80, 11.39 | ||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.91, 1.06 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.84, 1.02 | 0.11 |

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; ART, adjuvant radiation therapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy; SRT, salvage radiation therapy.

OS

KM estimates for OS at 5 and 10 years were 98.6% and 92%, respectively, for patients treated with ART and 95% and 80%, respectively, for patients treated with SRT. OS was not found to be significantly associated with treatment group (log-rank, P = 0.054). No variables were significantly correlated with OS on MVA performed, with or without propensity score adjustment (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Determining the optimal postprostatectomy therapy approach for patients with APFs—whether to use early ART or delayed, selective SRT—remains a source of controversy. Critics of ART have noted that, although ART is effective, a large percentage of patients with APFs remain disease-free without RT. In the aforementioned phase III trials comparing ART versus observation, roughly half of all patients randomized to initial observation never suffered a biochemical failure despite APFs.4,6,9 Thus, SRT may provide a more selective approach, where only those patients with recurrent disease are subjected to pelvic irradiation. Although it has been hypothesized that ART and early SRT are equivalent, there is not yet level I evidence to support this notion.

Comparative analyses performed on this subject are limited by an inherent bias that arises when comparing ART and SRT; patients treated with SRT have already suffered a biochemical recurrence, whereas patients treated with ART are all disease-free but have the potential to develop a biochemical recurrence in the future.10 Thus, patients treated with ART have a significant lead time bias when compared with patients treated with SRT.10 Moreover, the nonrandomized nature of observational studies also introduces an underlying selection bias into such analyses given that physicians may be more apt to recommend ART or SRT based upon different clinical and pathologic variables, further introducing the potential for confounding.

In the present analysis, we have attempted to account for some of these limitations by incorporating a propensity score into our MVA and by accounting for time between RP and RT. Propensity scores adjust for nonrandom treatment allocation in observational studies by incorporating known variables that may influence treatment decisions to account for selection biases for one treatment over the other.8 Propensity score analysis has been used previously in observational studies of prostate cancer treatments.11,12 Although matching by propensity score may address confounding in observational research, this approach cannot but account for unmeasured confounders.13 In this study, propensity score analysis was performed to adjust for some known potential confounding in the delivery of ART versus SRT.

An interesting finding from our study is that incorporation of the propensity score significantly impacts the observed influence of ART on FFBF. In a MVA performed without the use of propensity score adjustments, use of ART over SRT was associated with a highly significantly improved FFBF rate, which is consistent with previously published series.14,15 However, after incorporating the propensity score into our analysis, there was only a trend toward improved FFBF for ART (HR, 0.51; P = 0.06). These findings are especially interesting, given that the median time from RP to start of RT for patients is only 7 months, suggesting that the men requiring SRT may have had more aggressive disease. Taken together, these results highlight the impact of statistical methodology when comparing ART versus SRT, and this should be considered in future analyses of this subject.

A small percentage of patients included in our study did receive pelvic irradiation and/or neoadjuvant or concurrent ADT with prostatic irradiation. On MVA, the use of pelvic RT or ADT was not found to be prognostic factors associated with FFBF. Previous reports from Stanford University have demonstrated a benefit for patients treated with SRT who are treated with whole-pelvic RT and/or ADT.16 Preliminary results from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9601 also showed a biochemical relapse-free survival advantage in favor of patients receiving 2 years of bicalutamide therapy.17 Our study was likely underpowered to detect such an association. The issue of whole-pelvic RT ± ADT for patients in the salvage setting is currently being examined in another Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial (0534).

There are several limitations of the present analysis which are worth mentioning. Although use of a propensity score allows us to account for known covariates that would impact recommendation for ART or SRT, there are likely to be other unknown covariates which we were unable to account for. Moreover, we did not have data on the outcomes for patients with APFs who were not offered ART and never had a biochemical recurrence. This limitation, inherent in the study design, restricts the estimation of treatment effect from ART compared with SRT. Keeping this limitation in mind, our study does indicate that use of delayed, selective RT for the subset of patients with APFs who develop biochemical failure, is not an independent predictor for biochemical failure, distant metastasis, or OS when compared with patients receiving immediate, postprostatectomy RT. Finally, the timing of RT differs between the 2 groups, with ART delivered sooner after diagnosis and prostatectomy than SRT. To address this difference in the analyses of FFBF, DMFS, and OS, we included time from RP to RT as a factor in multivariable models.

There are currently 3 randomized clinical trials underway to compare ART to SRT. The first study, the RAVES study (Radiotherapy: Adjuvant vs. Salvage), which is being conducted by the Trans-Tasman Oncology Group.18 The primary outcome measure in this study will be biochemical failure (PSA≥0.4 ng/mL). The second study, the RADICALS (radiotherapy and androgen deprivation in combination after local surgery) trial, is being conducted by the Medical Research Council in the United Kingdom.19 Patients in this study will be randomized to receive ART or observation with SRT at the time of biochemical failure. Patients within each treatment arm will also be randomized to receive no ADT or ADT. The primary endpoint of the study will be cause-specific survival. The third study, the GETUG-17 (Groupe d’Etudes des Tumeurs Uro-Génitales) trial, is a phase III trial in which patients with a pT3–T4 or R1 disease will be randomized to receive either ART with hormonal therapy or delayed SRT with hormonal therapy at the time of a biochemical recurrence (> 0.2 ng/mL). The primary endpoint of the study will be event-free survival at 5 years.20

CONCLUSIONS

In our single-institutional analysis of long-term outcomes of patients treated with ART and SRT, we were unable to demonstrate a benefit for ART versus SRT with regard to FFBF, FFMF, or OS. Although we await the results of the ongoing phase III trials on the subject, future comparative studies on this subject should incorporate statistical methodologies that adjust for biases that arise with the use of observational cohorts of data, as these can significantly impact results. Furthermore, additional studies should focus on identifying subsets of patients who benefit more or less from ART versus SRT, as well as subsets of patients who may benefit from more intensive, combined-modality treatments.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation (T.N.S.), and by the Kimmel Cancer Center’s NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA56036.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Raldow A, Hamstra DA, Kim SN, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: evidence and analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephenson AJ, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, et al. Postoperative nomogram predicting the 10-year probability of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7005–7012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson GP, Riggs M, Hermans M. Pathologic findings at radical prostatectomy: risk factors for failure and death. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiegel T, Bottke D, Steiner U, et al. Phase III postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy compared with radical prostatectomy alone in pT3 prostate cancer with postoperative undetectable prostate-specific antigen: ARO 96-02/AUO AP 09/95. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2924–2930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Paradelo J, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathological T3N0M0 prostate cancer significantly reduces risk of metastases and improves survival: long-term followup of a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2009;181:956–962. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolla M, van Poppel H, Collette L, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: a randomised controlled trial (EORTC trial 22911) Lancet. 2005;366:572–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiber D, Rineer J, Yu JB, et al. Analysis of pathologic extent of disease for clinically localized prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and subsequent use of adjuvant radiation in a national cohort. Cancer. 2010;116:5757–5766. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson IM, Jr, Tangen CM, Paradelo J, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathologically advanced prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2329–2335. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King CR. Adjuvant versus salvage radiotherapy after prostatectomy: the apple versus the orange. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1045–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kibel AS, Cziezki JP, Klein EA, et al. Survival among men with clinically localized prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy in the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol. 2012;187:1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roobol MJ, Heijnsdijk EAM. Propensity score matching, competing risk analysis, and a competing risk nomogram: some guidance for urologists may be in place. Eur Urol. 2011;60:931–934. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor N, Kelly JF, Kuban DA, et al. Adjuvant and salvage radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:755–763. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trabulsi EJ, Valicenti RK, Hanlon AL, et al. A multi-institutional matched-control analysis of adjuvant and salvage postoperative radiation therapy for pT3-4N0 prostate cancer. Urology. 2008;72:1298–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King CR, Presti JC, Jr, Gill H, et al. Radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: does transient androgen suppression improve outcomes? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shipley WU, Hunt D, Lukka H, et al. Initial report of RTOG 9601: a phase III trial in prostate cancer: anti-androgen therapy (AAT) with bicalutamide during and after radiation therapy (RT) improves freedom from progression and reduces the incidence of metastatic disease in patients following radical prostatectomy (RP) with pT2-3, N0 disease, and elevated PSA levels. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:S27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundaresan P, Turner S, Kneebone A, et al. Evaluating the utility of a patient decision aid for potential participants of a prostate cancer trial (RAVES-TROG 08.03) Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:521–524. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker C, Clarke N, Logue J, et al. RADICALS (radiotherapy and androgen deprivation in combination after local surgery) Clin Oncol. 2007;19:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richaud P, Sargos P, Henriques de Figueiredo B, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Cancer Radiother. 2010;14:500–503. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2010.07.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]