SUMMARY

In patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and erosive esophagitis, treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is highly effective. However, in some patients, especially those with nonerosive reflux disease or atypical GERD symptoms, acid-suppressive therapy with PPIs is not as successful. Alginates are medications that work through an alternative mechanism by displacing the postprandial gastric acid pocket. This study performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the benefit of alginate-containing compounds in the treatment of patients with symptoms of GERD. PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane library electronic databases were searched through October 2015 for randomized controlled trials comparing alginate-containing compounds to placebo, antacids, histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), or PPIs for the treatment of GERD symptoms. Additional studies were identified through a bibliography review. Non-English studies and those with pediatric patients were excluded. Meta-analyses were performed using random-effect models to calculate odds ratios (OR). Heterogeneity between studies was estimated using the I2 statistic. Analyses were stratified by type of comparator. The search strategy yielded 665 studies and 15 (2.3%) met inclusion criteria. Fourteen were included in the meta-analysis (N = 2095 subjects). Alginate-based therapies increased the odds of resolution of GERD symptoms when compared to placebo or antacids (OR: 4.42; 95% CI 2.45–7.97) with a moderate degree of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 71%, P = .001). Compared to PPIs or H2RAs, alginates appear less effective but the pooled estimate was not statistically significant (OR: 0.58; 95% CI 0.27–1.22). Alginates are more effective than placebo or antacids for treating GERD symptoms.

Keywords: alginate, gastroesophageal reflux disease, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 25% of the Western population has symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) at least weekly.1 GERD also is among the most frequent reasons for outpatient gastroenterology consultation.2 Current professional guidelines recommend medical management of GERD primarily with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs),3,4 the most effective therapy for erosive esophagitis.5 In some patients with GERD symptoms, especially those with nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), suppression of gastric acid with PPIs is not as effective.3

An alternative approach to manage symptomatic GERD is to impede the flow of acidic refluxate. Alginic acid derivatives, or alginates, treat GERD via a unique mechanism by creating a mechanical barrier that displaces the postprandial acid pocket.6 In the presence of gastric acid, they precipitate into a gel and form a raft that localizes to the acid pocket in the proximal stomach.7 Although available in many countries over-the-counter for several decades, often in combination with antacids, this class of medications recently has been the focus of renewed research interest.8 By providing an impediment to distal esophageal acid exposure, alginates may be superior to other measures or particularly useful as an additional option for patients with GERD not responding to antisecretory therapy. In this study, we aimed to determine if alginate-containing compounds are an effective treatment for patients with symptomatic GERD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

Articles were identified by searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane databases through October 2015. Searches were based on controlled vocabulary including medical subject heading (MeSH) terms when possible (‘alginates’ and ‘gastroesophageal reflux’). In addition, relevant keywords and variations of root words were also included in the search (‘alginate,’ ‘alginic,’ ‘alginic acid,’ ‘alginic acid-polyethyl methacrylate,’ ‘algicon,’ ‘gaviscon,’ ‘pyrogastrone,’ ‘antacid,’ ‘antacid agent,’ ‘aluminum hydroxide,’ ‘magnesium trisilicate,’ ‘sodium bicarbonate drug combination,’ ‘gastro-oesophageal reflux,’ ‘gastrooesophageal reflux,’ ‘oesophageal reflux,’ ‘non-erosive reflux disease,’ ‘GERD,’ ‘GORD,’ ‘NERD,’ ‘NORD,’ ‘endoscopy negative reflux disease,’ ‘ENRD’). The search was conducted by combining terms representing disease therapies with terms representing the disease itself (for example, ‘alginates AND gastroesophageal reflux disease’). Next, the bibliographies of articles included in the final analysis as well as relevant reviews were screened for additional articles. Third, the website ClinicalTrials.gov was searched for additional studies not indexed in the above databases. Authors of relevant studies and manufacturers of alginate therapies (Reckitt-Benckiser, GlaxoSmithKline, and Prestige Brands) were contacted to inquire about completed studies not yet published. Two independent reviewers (DAL and BPR) evaluated articles at the title, abstract, and full-text review stages. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

All randomized controlled trials of alginates in adult patients (greater than 18 years of age) with GERD and written in English were included in the review. Exclusion criteria included studies that examined patients with erosive esophagitis, patients less than 18 years of age, studies that compared alginate formulations to each other and studies published as abstracts only. Using a standardized form, the two reviewers (DAL and BPR) independently extracted data for inclusion in the analysis and assessed trial risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.9 Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Pooled estimates for the effect of alginate-containing formulations compared with alternative therapies were computed for the outcome of GERD symptom relief, which was based on the definition provided in each study. The primary analyses were stratified by therapy type. Neither placebo and antacids nor alginates have long-term effects on GERD;10 therefore, the former were combined as a single comparator group (temporary acid neutralizing therapy) with alginates. Acid-suppressive therapies (PPIs and H2RAs) were the other comparison group. In one study with multiple experimental and control arms, groups with similar active components (alginate and alginate plus antacid) were combined to create a single pair-wise comparison (placebo);11 in another multiarmed study, similar control arms were combined (placebo and antacid) to create a pair-wise comparison with the active comparator (alginate plus antacid).12 Heterogeneity was analyzed by calculating the I2 measure of inconsistency and was considered statistically significant if I2 > 50% and P < 0.1 by the Chi-square test.

Pooled estimates were reported as odds ratios (ORs) derived from a random-effect model, given the potential for heterogeneity between studies. To examine potential contributors to heterogeneity, prespecified subgroup analyses were performed. Studies were grouped by geographic location, year of publication (prior to 1990 and after 1990), number of centers involved (single versus multicenter) and study duration (less than or equal to 2 weeks versus 1 month or greater). Contribution to heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 statistic to determine which factors eliminated or reduced heterogeneity to a minimal level (I2 < 50%). Given the overall small number of studies, there was insufficient power to assess for reporting bias using a Begg's test and it was therefore not performed.

All statistical analyses were performed using the STATA software (version 13.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX). All components of this study were exempted from approval by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania. The study was indexed within the PROSPERO register (2015:CRD42015017908).

RESULTS

Article search and identification

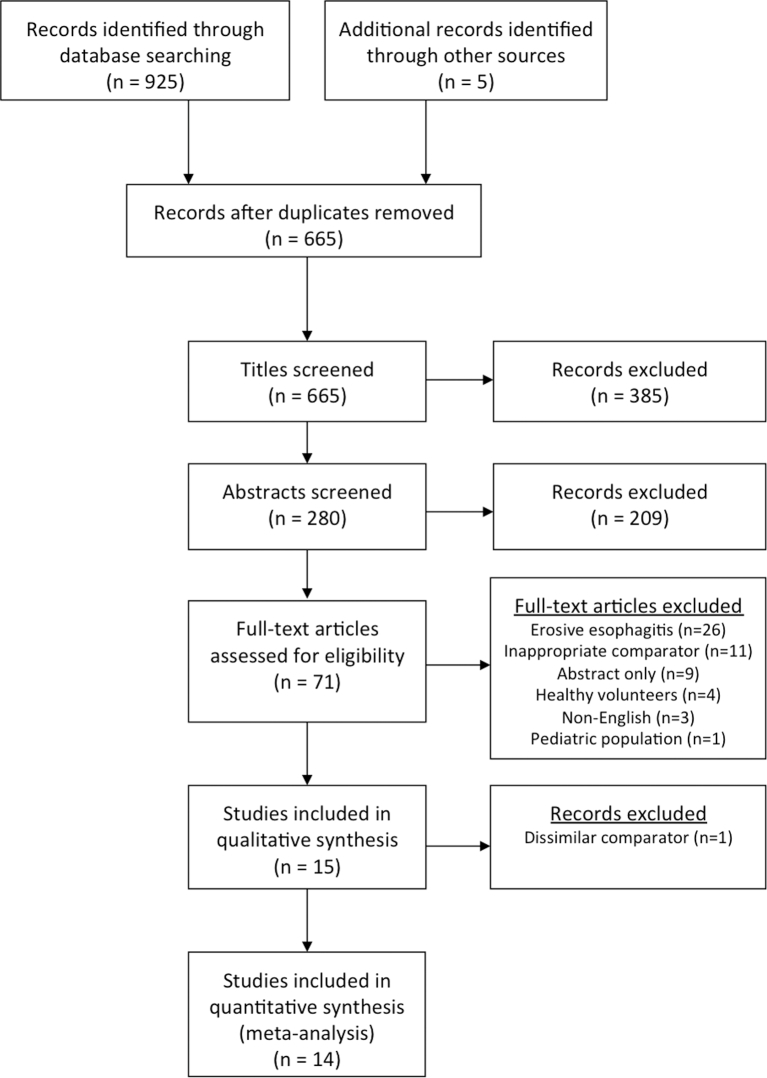

The initial database search identified 660 studies; five additional articles were found through a supplemental review (Fig. 1). After evaluating titles and abstracts, 594 studies were excluded. Of the remaining 71 studies, 15 met inclusion criteria after a fulltext review (Table 1). All studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Ultimately, 14 studies (N = 2095) were included in the meta-analysis and two separate comparisons were performed. Alginate-based therapies were compared to either placebo or antacid therapy in nine studies (N = 900) and to PPIs and H2RAs in five studies (N = 1195). The single study that was not included in a meta-analysis evaluated cisapride as a comparator, a drug no longer commercially available in many countries, and one that does not act via an acid-neutralizing or acid-suppressive mechanism.13

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of article search and identification.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in this systematic review

| Study | Study design | GERD diagnosis and/or severity | Comparators (N) | Duration (formulation) | Outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo or antacid as comparators | ||||||

| Beeley and Warner11 | Randomized, double-blind, three-arm cross-over Single Center | Typical symptoms and presence of hiatal hernia on barium | Alginate (28) vs. alginate + antacid (28) vs. placebo (28) | 2 weeks (Tablet) | Improvement in regurgitation | Alginate (19/28) vs. alginate + antacid (25/28) vs. placebo (12/28) |

| Stanciu and Bennett12 | Randomized, single-blind, three-arm parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms | Alginate + antacid (20) vs. antacid (20) vs. placebo (20) | 2 weeks (Tablet) | Global improvement of symptoms | Alginate + antacid (11/20) vs. antacid (5/20) vs. placebo (7/20) |

| Barnardo et al.14 | Randomized, double-blind cross-over single center | Typical symptoms and reflux on barium | Alginate + antacid (26) vs. antacid (26) | 6 weeks (Tablet) | Global acceptability of treatment | Alginate + antacid (21/26) vs. antacid (5/26) |

| Chevrel15 | Randomized, open-label, cross-over single center | Typical symptoms and reflux on barium | Alginate (44) vs. antacid (44) | 2 weeks (liquid) | Global improvement of symptoms | Alginate (37/44) vs. antacid (10/44) |

| Lang and Dougall16 | Randomized, parallel group multicenter | Reflux dyspepsia of pregnancy | Alginate + antacid (50) vs. antacid (47) | 2 weeks (liquid) | Improvement in nighttime reflux symptoms | Alginate (41/50) vs. antacid (36/47) |

| Chatfield17 | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 2 days/week | Alginate + antacid (46) vs. placebo (48) | 4 weeks (liquid) | Global improvement of symptoms | Alginate + antacid (39/46) vs. placebo (17/48) |

| Giannini et al.18 | Randomized, open-label, parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 3 days/week | Alginate + antacid (87) vs. antacid (92) | 2 weeks (liquid) | Complete absence of symptoms | Alginate + antacid (71/87) vs. antacid (68/92) |

| Lai et al.19 | Randomized, open-label, parallel group single center | Typical symptoms and EGD without erosions | Alginate (69) vs. antacid (65) | 6 weeks (tablet) | Global improvement of symptoms assessed by physician | Alginate (42/65) vs. antacid (18/56) |

| Thomas20 | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group single center | Typical symptoms ≥ 5 days/week | Alginate + antacid (56) vs. placebo (54) | 1 week (tablet) | Overall treatment response | Alginate + antacid (47/56) vs. placebo (34/54) |

| Proton pump inhibitor or histamine-2 receptor antagonist as comparators | ||||||

| Bennett et al.21 | Randomized, parallel group single Center | Typical symptoms and positive pH test | Alginate + antacid (19) vs. alginate + antacid + H2RA (17) | 6 weeks (tablet) | Global improvement of symptoms | Alginate + antacid (12/19) vs. alginate + antacid + H2RA (15/17) |

| Goves et al.22 | Randomized, single-blind, parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 2 days/week | Alginate (337) vs. PPI (333) | 2 weeks (liquid) | Complete resolution of symptoms | Alginate (27/337) vs. PPI (90/333) |

| Poynard et al.13 | Randomized, open-label, parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 2 days/week | Alginate (180) vs. 5HTR agonist (173) | 4 weeks (liquid) | Global improvement of symptoms | Alginate (158/180) vs. 5HTR agonist (120/173) |

| Manabe et al.23 | Randomized, open-label, parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 2 days/week and EGD without erosions | Alginate + PPI (26) vs. PPI (31) | 4 weeks (liquid) | Complete resolution of regurgitation | Alginate + PPI (18/26) vs. PPI (20/31) |

| Pouchain et al.24 | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 2 days/week | Alginate (120) vs. PPI (121) | 1 week (liquid) | Self-assessed heartburn/pain relief | Alginate (62/120) vs. PPI (74/121) |

| Chiu et al.25 | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group Multicenter | Typical symptoms ≥ 2 days/week and EGD without erosions | Alginate (92) vs. PPI (91) | 4 weeks (liquid) | Relief of heartburn or regurgitation | Alginate (49/92) vs. PPI (46/91) |

Typical symptoms include heartburn, volume regurgitation, dyspepsia, and/or retrosternal chest pain.

EGD, upper endoscopy; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; H2RA, histamine-2 receptor antagonist; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; UK, United Kingdom; 20 mg omeprazole daily; 5HTR, serotonin receptor, 20 mg cisapride daily; 400 mg cimetidine four times daily.

All studies evaluated symptomatic GERD response with improvement defined as either complete resolution or significant improvement in typical symptoms.

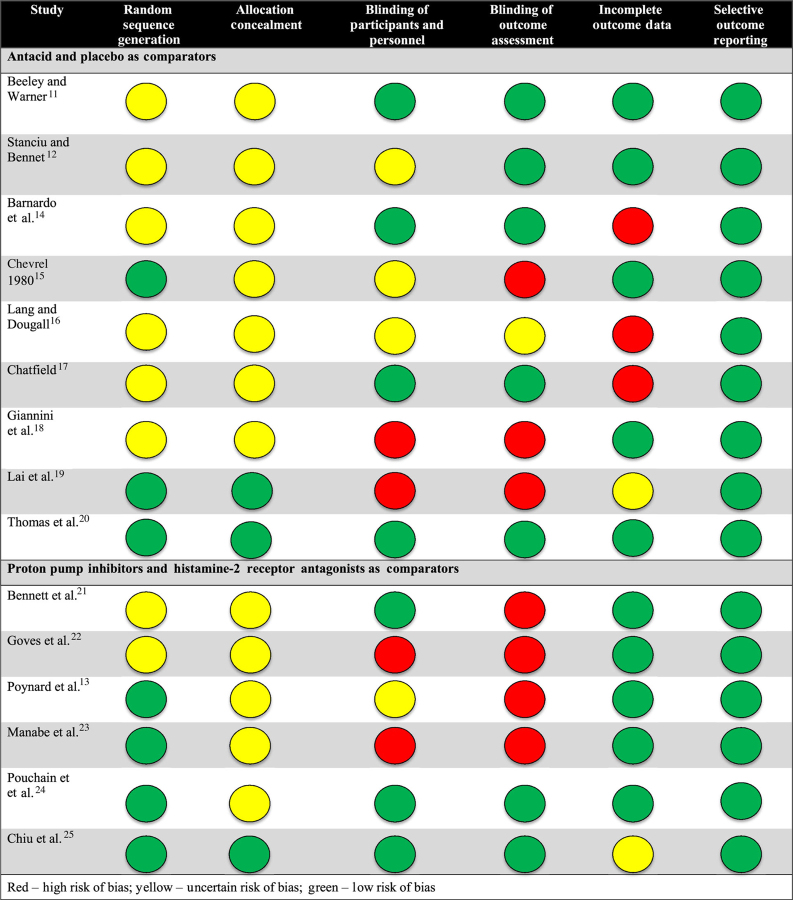

Despite all studies being RCTs, the risk of bias appeared most prominent with respect to detection (blinding of outcome assessment), performance (blinding of participants and personnel), and attrition (incomplete outcome data) across all studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment for studies included in this systematic review

|

Placebo and antacid therapy as comparators

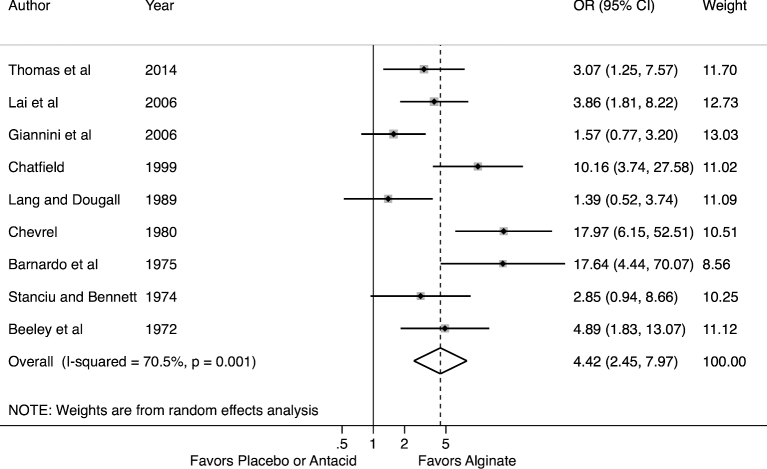

Alginate therapy was uniformly favored over placebo or antacids in all studies (Fig. 2). Overall, there was a statistically significant treatment benefit for alginate-based therapies with an odds ratio of 4.42 (95% CI 2.45–7.97). When excluding those studies with the largest treatment effects,14,15 the overall estimate did not change significantly. The heterogeneity between these studies was moderate (I2 = 71%, P = .001).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of meta-analysis for alginate therapy versus placebo or antacid.

We subsequently explored this heterogeneity through subgroup analyses. Geographic region (Europe versus Asia) and year of publication assessed by before or after 1990 did not account for the heterogeneity as results were stable by geographic region and over time. Study setting defined by single center or multicenter did not account for the heterogeneity. Study duration may have accounted for some of the heterogeneity as there was less heterogeneity when combining only those studies (N = 3) lasting longer than 2 weeks (I2 = 57%, P = 0.10).

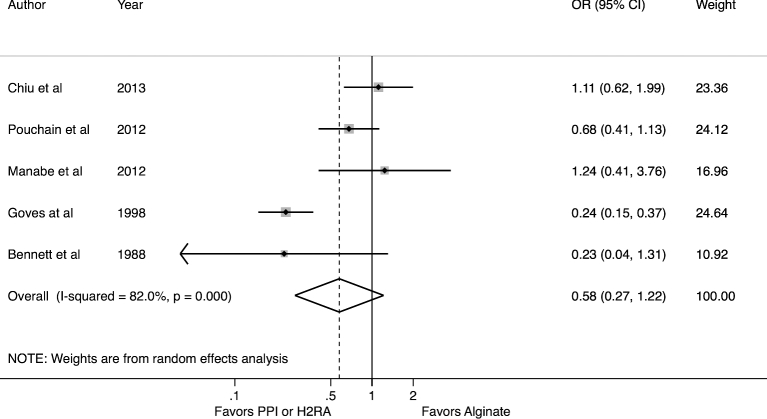

Proton pump inhibitor and histamine-2 receptor antagonist as comparators

Five studies evaluated alginate benefit versus acid-suppressive therapy with PPIs or H2RAs (Fig. 3). In four, alginate was compared against PPIs, while in the fifth a H2RA was the comparator. Measured against these comparators, alginates are not favored (OR: 0.58; 95% CI 0.27–1.22) but there was a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 82%, P < .001). There were too few studies to assess if specific subgroups accounted for the heterogeneity. When excluding the only study to examine H2RAs against alginates, the meta-estimate did not change significantly. Those studies published within the last 5 years (N = 3 studies) demonstrated less difference between therapies (OR: 0.88, 95% CI 0.61–1.26) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = .37).23–25

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of meta-analysis for alginate therapy versus proton pump inhibitors or histamine-2 receptor antagonists.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide a comprehensive estimate of the utility of alginate-based therapy in the management of adults with GERD symptoms. The pooled data from the clinical trials demonstrated that alginates are superior to placebo and antacids for controlling GERD symptoms in adults. In addition, we found that when compared to acid-suppressive therapy with PPIs or H2RAs, alginates alone appeared less effective but the pooled estimate was not statistically significant. While current treatment guidelines recommend the use of acid suppression as first-line therapy for patients with chronic GERD symptoms, many patients have only intermittent or mild symptoms. Our study suggests that alginates alone provide superior benefit over antacids and therefore they could be considered as an initial treatment for patients with mild GERD symptoms for whom chronic acid suppression was either undesirable or deemed unnecessary.

Alginate-based compounds have been available for several decades. In the United States, they are typically sold under the brand name Gaviscon in both tablet and liquid formulations, which are available without a prescription. These products cite their active ingredients as aluminum hydroxide and magnesium trisilicate or magnesium carbonate, respectively. Alginic acid is listed as an inactive ingredient. The brand name Gaviscon, however, is used to market alginate-based therapies in a number of other countries including Canada and throughout Europe. Formulations like ‘Gaviscon Acid Breakthrough’ in Canada lists alginic acid as an active ingredient, similar to ‘Gaviscon Advance’ in the United Kingdom. Recently, there has been a resurgence of interest in alginates as a therapy for GERD, including for patients with continued symptoms despite acid suppression therapy.8

A previous narrative review published in 2000 summarized the literature on alginate therapy.26 The review suggested superiority of alginates compared to placebo with at least equal efficacy compared to conventional antacids, although it was not limited to clinical trials. A 2006 meta-analysis favored alginate therapy over placebo.27 However, Tran et al. included only three studies, all of which compared placebo to an alginate–antacid combination and thus may have overestimated the treatment effect of alginates. Several individual studies have been published since that time further evaluating the role of alginates compared to placebo and antacids as well as investigating alginates versus acid-suppressive therapy with PPIs.18–20,23–25 Therefore, we performed an updated systematic review and meta-analysis.

We evaluated the benefit of alginates compared to other forms of medical therapy for symptomatic GERD. We excluded studies of erosive esophagitis, for which PPIs are clearly indicated as first-line therapy.28,29 All studies included in our analysis required patients to have typical symptoms of GERD, but entrance criteria for many did not require endoscopy or ambulatory pHmetry. Therefore, it is likely that some of the patients in these studies had erosive esophagitis. It is expected that alginate therapy would be less effective for erosive esophagitis and as such we may have under estimated the therapeutic benefit relative to placebo or antacids.

An earlier meta-analysis found PPIs modestly beneficial compared to H2RAs and prokinetics for endoscopy-negative reflux disease;30 our analysis slightly favors PPIs compared to alginates, though the results were not statistically significant. In contrast, in both of the studies that compared alginates to PPIs among patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease alginates were slightly favored but this did not meet statistical significance.23,25 While increasing evidence points to alginates displacing the postprandial acid pocket and inhibiting acid exposure in the esophagus, the precise mechanism of action of alginates remains uncertain.6,31 Patients with nonerosive reflux and GERD symptoms may be deriving additional benefit through mechanical or other mechanisms independent of displacing or neutralizing the acid pocket.

Among the strengths of the current study is the more robust pooled estimate versus the previous work. The majority of clinical studies on alginates are European so we performed an Embase search, which includes in-depth indexing of pharmaceuticals as well as a richer source of European journals than MEDLINE/PubMed alone.32 Also, we compared alginates and combination alginates plus antacids to placebo and antacids alone, respectively, to assess for the effect of the alginate. While some formulations of alginate-containing therapies include an antacid, there is no evidence that antacids significantly improve GERD beyond immediate and temporary symptom relief and alginates themselves have only minimal acid neutralizing effects.10,33 Adding an active ingredient as a comparator might be expected to diminish the difference in measured efficacy of the two treatments. However, the benefit of alginates was substantial and independent of whether antacids were part of the alginate formulation.

We observed heterogeneity in the results of the clinical trials. Some differences between studies were evident such as criteria used for diagnosing GERD. This is not entirely unexpected given that included studies were performed over the course of more than 40 years. However, severity of GERD symptoms was moderate to severe and mostly similar between studies, even when comparing those performed prior to and following publication of the Montreal Consensus requiring typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation to occur at least 2 days per week.34 Study duration may have accounted for some of the observed heterogeneity in studies comparing alginates to placebo or antacids. This may relate to the transient efficacy of placebo and antacids in clinical trials. The response rate of placebo- or antacid-treated patients in trials with durations greater than 2 weeks was approximately 31% as compared to 56% among trials that were two weeks of duration or less. In contrast, the overall response rate in the active treatment arms was relatively similar regardless of treatment duration.

Across studies, there were small differences in endpoints with most evaluating for either subjective improvement or complete elimination in global GERD symptoms, though some evaluated for more specific findings such as regurgitation or pregnancy-related reflux. As a result, it is not possible to determine which population is definitively most likely to benefit from alginate therapy. Instead, our data provide more general support for the value of alginates, particularly with renewed interest in minimizing PPI usage.35 Further trials are needed to focus on whether there is an adjunctive benefit to adding alginate for those already on acid suppression or if there is a specific patient group for whom alginates are most effective.

In summary, data from the available clinical trials support the efficacy of alginates for the treatment of symptomatic GERD. They were superior to placebo and antacids. These data also support the need for larger randomized controlled trials of alginates plus PPIs to test their efficacy as an adjunctive agent in patients on acid suppression with incomplete symptom control.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH/NIDDK: T32 DK007740 (DAL) and K24 DK078228 (JDL).

References

- 1. El-Serag H B, Sweet S, Winchester C C, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2014; 63: 871–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hershcovici T, Fass R. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease that does not respond well to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010; 26: 367–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katz P O, Gerson L B, Vela M F. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 308–28; quiz 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kahrilas P J, Shaheen N J, Vaezi M F. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1383–91, 91 e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fass R. Proton pump inhibitor failure–what are the therapeutic options? Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(Suppl 2): S33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Ruigh, Roman S, Chen J, Pandolfino J E, Kahrilas P J. Gaviscon double action liquid (antacid and alginate) is more effective than antacid in controlling postprandial oesphageal acid exposure in GERD patients: a double-blind crossover-study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40: 531–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rohof W O, Bennink R J, Smout A J, Thomas E, Boeckxstaens G E. An alginate-antacid formulation localizes to the acid pocket to reduce acid reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 1585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sifrim D, Penagini R. Capping the gastric acid pocket to reduce postprandial acid gastroesophageal reflux. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 1592–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higgins J P T, Altman D G, Sterne J A C (eds). Chapter 8: Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. In: Higgins J P T, Green S. (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katz P O, Stein E M. The Esophagus, 5th edn Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beeley M, Warner J O. Medical treatment of symptomatic hiatus hernia with low-density compounds. Curr Med Res Opin 1972; 1: 63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stanciu C, Bennett J. Alginate/antacid in the reduction of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Lancet 1974; 303: 109–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poynard T, Vernisse B, Agostini H. Randomized, multicentre comparison of sodium alginate and cisapride in the symptomatic treatment of uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: 159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnardo D E, Lancaster-Smith M, Strickland I D, Wright J T. A double-blind controlled trial of ‘Gaviscon’in patients with symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Curr Med Res Opin 1975; 3: 388–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chevrel B. A comparative crossover study on the treatment of heartburn and epigastric pain: liquid Gaviscon and a magnesium-aluminium antacid gel. J Int Med Res 1980; 8: 300–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lang G D, Dougall A. Comparative study of Algicon suspension and magnesium trisilicate mixture in the reatment of reflux dyspepsia of pregnancy. Br J Clin Pract Suppl 1989; 66: 48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chatfield S. A comparison of the efficacy of the alginate preparation, Gaviscon Advance, with placebo in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Curr Med Res Opin 1999; 15: 152–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giannini E G, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P et al. A comparison between sodium alginate and magaldrate anhydrous in the treatment of patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Dig Des Sci 2006; 51: 1904–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai I R, Wu M S, Lin J T. Prospective, randomized, and active controlled study of the efficacy of alginic acid and antacid in the treatment of patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12: 747–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas E, Wade A, Crawford G, Jenner B, Levinson N, Wilkinson J. Randomised clinical trial: relief of upper gastrointestinal symptoms by an acid pocket-targeting alginate-antacid (Gaviscon Double Action) - a double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bennett J, Buckton G, Martin H, Smith M R. The effect of adding cimetidine to alginate-antacid in treating gastro-esophageal reflux. Diseases of the Esophagus: Springer; 1988: 1111–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goves J, Oldring J K, Kerr D et al. First line treatment with omeprazole provides an effective and superior alternative strategy in the management of dyspepsia compared to antacid/alginate liquid: a multicentre study in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: 147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manabe N, Haruma K, Ito M et al. Efficacy of adding sodium alginate to omeprazole in patients with nonerosive reflux disease: a randomized clinical trial. Dis Esophagus 2012; 25: 373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pouchain D, Bigard M-A, Liard F, Childs M, Decaudin A, McVey D. Gaviscon vs. omeprazole in symptomatic treatment of moderate gastroesophageal reflux. a direct comparative randomised trial. BMC Gastroenterol 2012; 12: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chiu C T, Hsu C M, Wang C C et al. Randomised clinical trial: sodium alginate oral suspension is non-inferior to omeprazole in the treatment of patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38: 1054–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mandel K G, Daggy B P, Brodie D A, Jacoby H I. Review article: alginate-raft formulations in the treatment of heartburn and acid reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000; 14: 669–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tran T, Lowry A M, El-Serag H B. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of over-the-counter gastro-oesophageal reflux disease therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gralnek I M, Dulai G S, Fennerty M B, Spiegel B M. Esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors in erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 1452–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boeckxstaens G, El-Serag H B, Smout A J, Kahrilas P J. Symptomatic reflux disease: the present, the past and the future. Gut 2014; 63: 1185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van Pinxteren B, Numans M E, Bonis P A, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database System Rev 2006: CD002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kahrilas P J, McColl K, Fox M et al. The acid pocket: a target for treatment in reflux disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 1058–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Topfer L A, Parada A, Menon D, Noorani H, Perras C, Serra-Prat M. Comparison of literature searches on quality and costs for health technology assessment using the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1999; 15: 297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tytgat G N, Simoneau G. Clinical and laboratory studies of the antacid and raft-forming properties of Rennie alginate suspension. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 23: 759–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vakil N, van Zanten S V, Kahrilas P et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 1900–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heidelbaugh J J, Goldberg K L, Inadomi J M. Overutilization of proton pump inhibitors: a review of cost effectiveness and risk [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(Suppl 2): S27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]