Abstract

Resilience has received increased attention among both practitioners and scholars in recent years. Child resilience has received notable attention in disaster risk reduction (DRR) during the creation of the Sendai Framework 2015–2030 to improve child protection in the event of disasters. As resilience is a subjective concept with a variety of definitions, this study evaluates its different factors and determinates in the existing research to clarify the path for the near future and objective research. A systematic literature review was conducted by searching and selecting the peer-reviewed papers published in four main international electronic databases including PubMed, SCOPUS, WEB OF SCIENCE, and PsycINFO to answer the research question: “What are the criteria, factors or indicators for child resilience in the context of a natural disaster?” The process was based on PRISMA guidelines. In total, 28 papers out of 1838 were selected and evaluated using thematic analysis. The results are shown in two separate tables: one descriptive and the other analytical. Two main themes and five subthemes for criteria for child resilience in a disaster have been found. The factors found cover the following areas: mental health, spiritual health, physical, social behavior, and ecological, and as well as environmental. The majority of the included studies mentioned the scattered criteria about children resilience without any organized category. Although this concept is multifactorial, additional research is needed to develop this study and also observe other kinds of disasters such as human-made disasters.

Keywords: Adolescent, children, disaster risk reduction, natural disaster, resilience

Introduction

Many countries in the world are constantly experiencing disasters of different kinds. Each year, children as the large group in the population are severely affected by these.[1,2,3,4,5] For instance, based on findings by the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in 2007, approximately 200 million children experienced physical disabilities due to disasters (or physical injuries due to disasters) in the world.[6] Many studies have already focused on the vulnerability of children in disasters,[7,8,9,10] but little is to be found regarding children's capacity in a disaster situation. Recently, children have played a significant role in disaster risk reduction (DRR) during floods in Bangladesh[3] and actively participating in the Third United Nations World Conference on DRR (WCDRR),[11] but their voice has rarely been heard in DRR.[1] However, youth and adolescents have the capacity to make a contribution in the fields of science, practice, and innovation.[11]

Furthermore, the Hyogo Framework for Action (2005–2015) emphasized preparedness and education to build resilience and a safety culture at all levels,[12,13] and the Sendai Framework DRR (2015–2030) has focused on youth participation and activities in DRR, and their feedback is seen as an important resource.[11] Accordingly, knowing the capacity and resiliency of children is essential in DRR. Resilience is a multifactorial term which has been given several definitions in different fields such as health and psychology.[14,15,16] According to the researchers’ claim, use of the term resilience in the scientific literature has increased eight times more than the previous years,[17] and it also has increased in policy making as well as in practice.[18]

Research has shown that while there are a lot of studies about psychological resilience in children,[19,20,21,22] little is known about the integrated domains and the criteria for this resilience, particularly in disasters. Furthermore, the available studies did not provide any logical model for child resilience. On the other hand, the definitions of resilience are as various as the diversity of the fields. The term “resilience” comes from the field of psychology which is rich in explanations, but resilience is new in research about disasters and DRR. Furthermore, the criteria and domains of resilience have been limited mainly to the psychosocial field. In this study, the Newman and Tango (2012) definition of resilience is used: the “individual ability to adapt to the tragedy, trauma, adversity, hardship, and ongoing significant life stressors and also to anticipate, tolerate and bounce back from external shocks, and pressures in their life to avoid more vulnerability”.[23,24] In fact, assessing the resilience criteria is essential to identify children's capacities and capabilities.[25] To the best of our knowledge, no systematic approach has been found to child resilience, hence, this systematic literature review has been conducted to determine the criteria and domain of children's resilience in disasters, to define their capacity and ability. The study results can be useful for decision-makers, policymakers, and also for those who are responsible for children's safety in communities.

Methods

Strategy of systematic review

This study was a systematic literature review, which has registered on the PROSPERO website.[26] The study was developed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Data Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.[27] It started with these research questions: “What are the elements, criteria, and capacity of children in the context of a natural disaster?” “what would be the resilient children criteria on which we can rely in disasters?” It should be mentioned that the definition of children was based on that of the UNICEF: “a child means every human being under 18-years-old.”[28]

Data sources

A systematic search took place during a 3-month period from June 14, 2016 to August 4, 2016. The sources consisted of PubMed, SCOPUS, WEB OF SCIENCE, and PsycINFO. There was no time limitation for included articles. To find gray literature, special databases such as UNICEF, ERIC, UNISDR, APA PsycNET, Global Platform on DRR, and International Building Resilience Conference were searched. All kinds of available electronic resources were included such as books, international reports, and workshops related to the research question.

Database searching

The initial search process was conducted to find an answer to the research objectives with no limitation on language and time period. The MeSH index was used to find keywords. Furthermore, experts were consulted and the related articles were examined. Each database had its own syntax for searching, for example, search terms for PubMed were Resilient* and [Child* or youth or adolescent* or young or teen*] disaster, title, abstract, headwords, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests, and measures).

Data extraction

All search results were imported into EndNote basic software version 15, which is free source. Initially, duplicated articles were removed in the study. Then the articles evaluation was started using title, abstract, and keywords as the inclusion criteria. Following that, the full texts of the remaining peer-reviewed articles were evaluated considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria and standard quality assessment.[29,30,31]

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

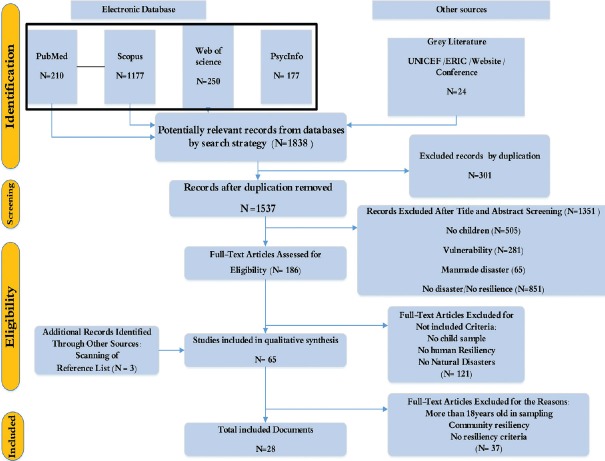

The inclusion criteria included any studies pertaining to human resiliency, children, and natural disasters. It has been guided to find out “what are the children resilience criteria and the potential capacity of children in natural disasters?” among final selected peer-reviewed articles by content analysis approach. As exclusion criteria, the articles which were about human-made disasters, emergencies, clinical issues, vulnerability, post-traumatic stress disorder, people more than 18-year-old, community resilience, and nonhuman resilience were removed in this study [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The Flow diagram of the search and paper selection

Results

In the process of this systematic literature review data analysis, the findings were divided into two groups: descriptive and analytical. Finally, based on the factors, a logical model for child resilience in disasters was created by the authors.

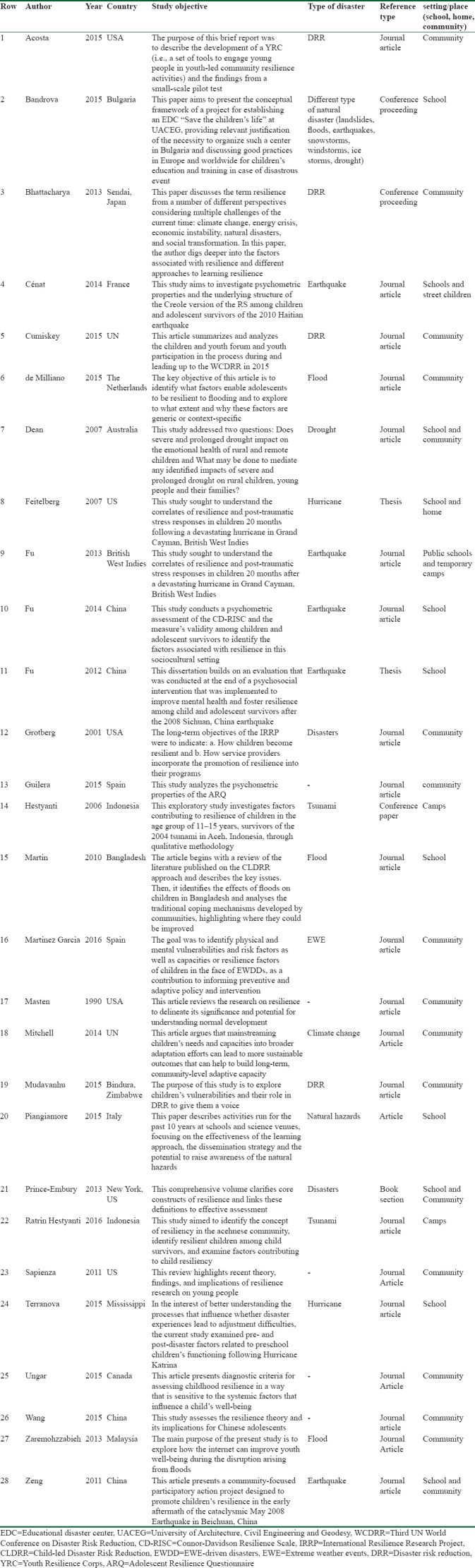

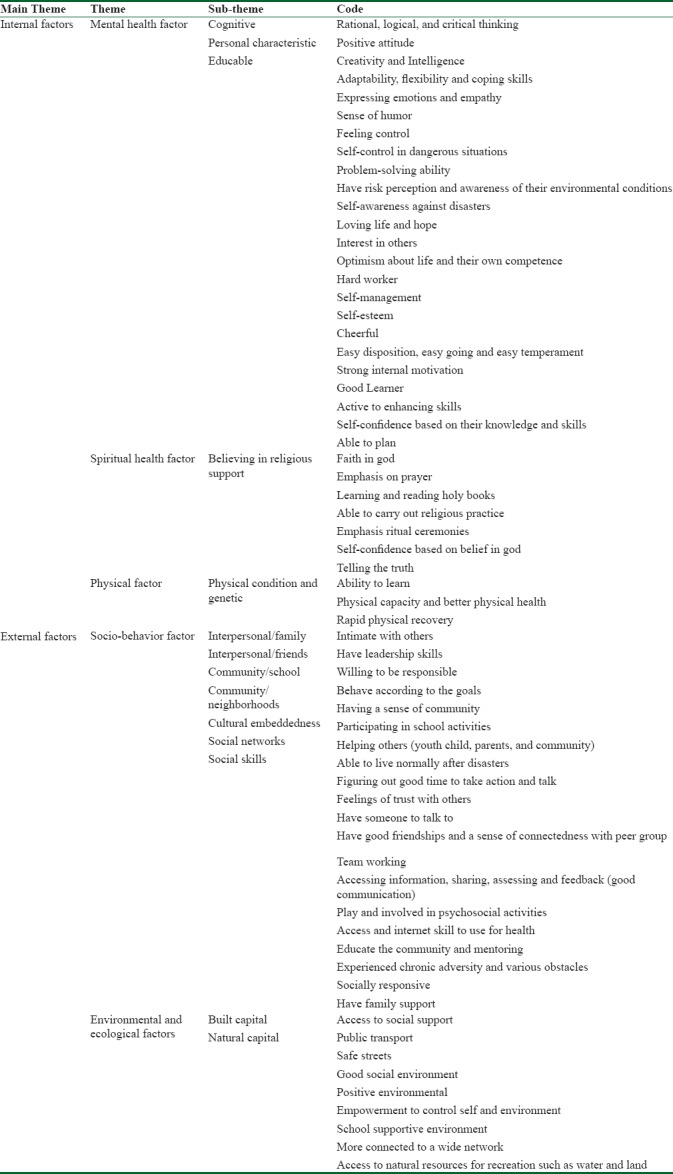

In the descriptive group, 1838 potentially relevant results were included from the electronic database including PubMed, Scopus, the web of science, PsycINFO, and gray literature (UNICEF, ERIC, and Conference) since 14th June till 4th August 2016. After that, 301 duplicated records were discarded and the 1537 remaining ones were reviewed; 1351 were excluded because of nonrelevant title and abstract. Then, the eligibility of the 186 articles was considered, and the documents were discarded which were not about children, natural disaster, resilience, or vulnerability issues. Moreover, 65 documents and 3 relevant articles from the articles’ references were added. Finally, a full-text review of these articles led to 28 documents, which were peer-reviewed articles, books, theses, and conference articles, which were included in the analysis [Table 1]. The selected peer-reviewed articles were carefully evaluated to find child resilience criteria based on content analysis as an analytical part, which led to 600 codes. The categories of the finding criteria were organized in three domains as the theme, subtheme, and code. After several meetings and discussions between co-authors, an agreement was reached on categories; and the adjusted table was created with two main themes and five sub-themes [Table 2].

Table 1.

Analyzed peer-reviewed articles details for systematic literature review

Table 2.

Classification of the dependent children resilience factors in DRR

As shown in Table 1, among 28 final documents including peer-reviewed articles, thesis, and conference papers, it showed that although the interest in research about resilience for children began in 1990;[32] the attention to this topic has increased in recent years. All 28 studies were conducted in the context of different types of natural disaster covering landslides, floods, earthquakes, tsunami, drought, hurricane, and climate change. The most common contexts of those studies were not only communities and societies but also schools, family, and camps, which were also of considerable interest for researchers. Table 1 indicates the descriptive results of the included peer-reviewed articles [Tables 1 and 2].

Furthermore, as latent content analysis, the 28 evaluated peer-reviewed articles were about natural disasters, DRR issues, factors, or domains of child resiliency. The peer-reviewed articles were coded separately, and in total, 600 codes about resiliency were found. Those codes were evaluated and organized based on the WHO definition of health in 1948 “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.[33] Table 2 presents the categorization of the child resilience criteria.

The research findings were categorized into two groups: internal (personal characteristics) and external (social behavior) factors. The internal factors consisted of mental health, spiritual health, and physical factors. Furthermore, the external factors included socialbehavior, ecological factors, and environmental factors.

A logical model is presented to shows factors that affect child resilience in a disaster [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 2.

The L.M “CRID” model as child resilience indicators in disasters

Discussion

This systematic literature review has been conducted to determine the criteria and domains of children's resilience in disasters. Moreover, it is conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Data analysis guidelines.[27] In this research, the most important findings are the development of a conceptual model called LM-CRID for children's resilience in disasters. The second findings denote the two groups: descriptive and analytical categories.

Based on the descriptive findings, the 28 final peer-reviewed articles were extracted including comprehensive criteria about children's resilience in DRR. In the analytical section, the extracted classifications are mentioned as internal and external criteria. Of the studies of children in disasters, there were few studies on their capacity, even in the rescue studies, and far more emphasis has been put on their vulnerability, and few have examined childhood resilience cases. However, in this study, children were considered as a group with a specific focus on their ability and capacity to reduce the risk of disasters. In this regard, on the basis of the previous peer review, a logical model of the resiliency of children in a disaster has not been presented so far. In addition, the review of the articles showed that the studies conducted in these papers did not have a comprehensive approach to children's resilience. Some of the components of resilience, including the individual, and society, and mental health separately no holistic approach.[19,20,21,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]

Given the mental and emotional tenacity of children, mental health is one of the significant components of their resilience; however, the damage they endure has been the main subject of research by past researchers. 1838 initial searches in this study were devoted to children's psychological vulnerability.

Moreover, among selected studies referring to children's resilience in disaster situations, each study had a particular view according to their background. For example, the Netherlands study is about factors which enable adolescents to be resilient in a flood disaster whereas[44] mentioned the individual, social, and environmental factors of child resilience. Moreover, the Indonesian study investigated factors contributing to resilience among survivor children in the age group of 11–15 years,[45] referred to spiritual health topics considering the importance of the issue of personal-social factors. Studies conducted by Piangiamore,[46] Martin,[3] and Mudavanhu et al.[1] are more specialized in DRR and have addressed the status and importance of the component of perceived disaster risk, which could be one of the most important factors in children's resilience, and are included in the international documents, including the new version of the Sendai framework (2015–2030) which emphasized the necessity of disaster risk perception in all society groups.[40] The new version of the International Sendai Framework Document emphasizes the important potential of children participation in disasters, but it does not provide any explanation for their resilience, and it is expressed in general terms.[40,47] Although attention to children as an independent group in this international context is a milestone for recent studies by scholars, new studies suggest that this is starting to change.[48]

None of the 28 final selected articles in the present study addresses the set of factors for the rescue of children in disasters as an individual topic, but each of them directly or indirectly pointed to factors of child resilience. In general, it seems that due to the lack of comprehensive integration of human components of child resilience, their resilience is neglected due to their capacity, and each researcher who studied it based their work on their own point of view. It attempted to classify the components of resilience with a holistic approach to health according to the WHO definition of health.[33] However, in the criterion of culture in resilience, it should not be forgotten that different cultures can add or diminish the components.

The current systematic literature review has attempted to present the resilience problem as a practical application in children and classifies examples of the individual, social, physical, spiritual, ecological, and environmental factors according to previous studies, which can integrate their results into this study. The logical model of children's resilience in disasters is schematically illustrated to summarize the significant domains; a clearer explanation is given here. The mental health domain encompasses the main group of children's resilience criteria in distress, it dates back to the 1970s.[49]

Several studies postulate the direct relationship between mental health and child resilience.[20,41,50] For example, Fu's study on the impact of China's earthquake on children's health in 2008 has been successful in improving their mental health resilience after the earthquake.[43] On the other hand, Grotberg assumes resilience as a human capacity that is effective in overcoming problems and disasters, furthermore, it is a contributing factor in mental health.[34]

In the present study, three subsets of cognitive factors, personality traits, and children's education have been considered for mental health. To give an example of cognitive cases, positive thinking and critical thinking should be mentioned. In terms of personality, the trait is categorized into creativity and intelligence, adaptability, flexibility and coping skills, expressing emotion and empathy, sense of humor, feeling of control, self-control in dangerous situations, and problem-solving ability.

According to the Hyogo framework, education has a vital role to play in disaster planning and building community resilience and is vital to build societies and improves people's readiness in the future. Well-organized disaster education programs for school children can be an important factor and a measure of effectiveness for communities. It is important to note that children have the ability to transfer disaster risk messages to their families and communities.[3] Although knowledge enhancement cannot be sufficient alone, it is also important to change people's behavior to reduce the risk and improve their readiness for other parts of the disaster management cycle.[3] In addition, a school can be one of the best places to reach the goal of promoting knowledge.[13] Johnson's study, “Evaluating Children's Learning of Adaptive Response Capacities from Shakeout, an Earthquake and Tsunami Drill in Washington State School Districts,” confirmed that school emergency drills have a major role in improving children's resilience.[51] In the last 3 years, a project presented by the Prevention and Crisis Management team in Tehran has been launched in schools to educate both students and teachers, as well as school administrators, about natural disaster risk perception such as an earthquake. Moreover, more focus is put on the structural safety of schools so that not only managers and teachers but also children can be better prepared against earthquake hazards.[52] As Oktar points out, the school is a very appropriate place for children to learn about DRR.[13] Based on the above, it seems necessary to use local methods to develop and improve education and increase the children's resilience.

Spiritual health as internal criterion directly related to calmness. Disasters cause high stress not only in children but also in adults. Therefore, having strong cognitive factors and enhancement of robust mental health can bring much relief and comfort to people during and after disasters.

The second group of external factors includes behavioral, social, environmental, and ecological ones that affect the resilience of children as internal factors. Since each person's health is an interaction between themselves and their community,[53] social-behavioral factors can be an important issue in boosting resilience. Interacting and communicating with others can help children to be resilient, and their interest in participating in social programs should be nurtured and their opinion listened to, and they should be encouraged to participate in social participation.[1]

Moreover, this study has referred to how to properly connect with peers, teachers, friends, and other members of the society, another important resilience measure. As Masten commented in a study on homeless and sheltered children, it was confirmed that resilient children get along better with teachers and their peers and display better social behaviors with others,[32,49] helping others has been confirmed in other texts.[37,45,54] In fact, resilient children tend to do help out more. In addition, the participation of children in planning and decision-making in disaster situations not only improves their planning but also their resilience. Mudavanhu et al.[1] examined this issue, listening to children's opinions in his study to show the importance of the children's presence in risk reduction planning. Although Acosta has spoken of involving children in disaster planning as an accepted issue, it is still not a widely practiced, and their presence still has several limitations.[19]

It is necessary to have a resilient community, a resilient family, and to have resilient children. The local culture of each region must be taken into account and efforts should be made to use it in the implementation of social activities and the public participation of children. The external criterion was environmental and ecological factors that affect children's resilience, which should be considered for resilience development. In some studies of those experiencing difficult conditions, encountering barriers to survival have been considered effective measures for developing resilient children.[2,32] Resilience is a construct that leads to self-safety and health; this is an issue that if solved, may provide happiness for children in the community.[55] According to Lueger-Schuster,[56] it must be mentioned that the tolerance ability of children is different, and a resilient child cannot overcome all hardships.

However, according to the above-mentioned conditions can lead to a different degree of resilience for children in different parts of the world. It should be noted that the findings of this study are qualitative, and it is necessary for these areas to be quantitatively measured in the future. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to design a suitable and specific tool for measuring children's resilience in disasters. The research team has created the model and has conducted this systematic study to provide basic information for future research.

Limitations

Only articles in English were included in this systematic literature review. We had limited access to the full text of four journals and three books; however, based on their abstracts, there is little doubt that they were relevant.

Conclusions

This study focuses on peer-reviewed documents to highlight the determinants of child resilience in disasters and emergencies. However, the lack of an integrated study led to this systematic literature review; it has found two main themes and five subthemes that consist of the internal factors of mental health factor, spiritual health factor, and physical factor. Since children can be an important group in a disaster, the concept of resilience and the provision of objective evidence can make the interventions more realistic and fruitful. This can, perhaps, lead to fundamental changes planning for children to make them more resistant to DRR and will be appropriate for their resilience in DRR programs. Therefore, this study can help planners and policymakers of disaster risk management and child health-care providers by identifying resilience and clarifying its components that should be considered in future decisions and plans and have a beneficial effect on children and teenagers in the near future. It should also be noted that considering the qualitative nature of this study, the necessity of a quantitative study and the provision of a resilience measurement is important, and the researcher will seek to respond to future studies which are currently underway by the research team.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study has been conducted as a part of a PhD program at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

- 1.Mudavanhu C, Manyena SB, Collins AE, Bongo P, Mavhura E, Manatsa D. Taking Children's Voices in Disaster Risk Reduction a Step Forward. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science. 2015;6:267–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osofsky JD. Clinical Work with Traumatized Young Children. New York, US: Guilford Press; 2011. Young children and disasters: Lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina about the impact of disasters and postdisaster recovery; pp. 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin ML. Child participation in disaster risk reduction: The case of flood-affected children in Bangladesh. Third World Q. 2010;31:1357–75. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2010.541086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Milliano CWJ. Luctor et emergo, exploring contextual variance in factors that enable adolescent resilience to flooding. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2015;14:168–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, Ball S, Bell S, Bellamy R, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and university college London institute for global health commission. Lancet. 2009;373:1693–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peek L, Stough LM. Children with disabilities in the context of disaster: A social vulnerability perspective. Child Dev. 2010;81:1260–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams ZW, Sumner JA, Danielson CK, McCauley JL, Resnick HS, Grös K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD and depression among adolescent victims of the Spring 2011 tornado outbreak. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:1047–55. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eksi A, Braun KL. Over-time changes in PTSD and depression among children surviving the 1999 Istanbul earthquake. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:384–91. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanter RK. Child mortality after hurricane katrina. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4:62–5. doi: 10.1017/s1935789300002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ardino V. A handbook of research and practice. John Wiley and Sons; 2011. Post-traumatic syndromes in childhood and adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cumiskey L, Hoang T, Suzuki S, Pettigrew C, Herrgard MM. Youth participation at the third UN world conference on disaster risk reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2015;6:150–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izadkhah YO, Hosseini M. Towards resilient communities in developing countries through education of children for disaster preparedness. International Journal of Emergency Management. 2005;2:138–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oktari RS, Shiwaku K, Munadi K, Syamsidik, Shaw R. A conceptual model of a school-community collaborative network in enhancing coastal community resilience in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015;12:300–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown R. Building children and young people's resilience: Lessons from psychology. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015;14:115–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohrs JC, Christie DJ, White MP, Das C. Contributions of positive psychology to peace: Toward global well-being and resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68:590–600. doi: 10.1037/a0032089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinelt T, Schipper M, Petermann F. Different pathways to resilience: On the utility of the resilience concept in clinical child psychology and child psychiatry. Kindheit Entwickl. 2016;25:189–99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ager A. Annual research review: Resilience and child well-being – Public policy implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:488–500. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller L, Quine CP. Resilience and tree health: A basis for implementation in sustainable forest management. Forestry. 2016;89:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acosta J, Towe V, Chandra A, Chari R. Youth resilience corps: An innovative model to engage youth in building disaster resilience. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10:47–50. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JL, Zhang DJ, Zimmerman MA. Resilience theory and its implications for Chinese adolescents. Psychol Rep. 2015;117:354–75. doi: 10.2466/16.17.PR0.117c21z8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cénat JM, Derivois D. Psychometric properties of the creole haitian version of the resilience scale amongst child and adolescent survivors of the 2010 earthquake. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connor KM, Zhang W. Recent advances in the understanding and treatment of anxiety disorders. Resilience: Determinants, measurement, and treatment responsiveness. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:5–12. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900025797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IFRC. World Disasters Report 2015: Focus on Local Actors, the Key to Humanitarian Effectiveness. Report No: 978-92-9139-226-1. 24 September. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman R. APA's Resilience Initiative. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2005;36:227. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheraghi MA, Ebadi A, Gartland D, Ghaedi Y, Fomani FK. Translation and validation of “Adolescent resilience questionnaire” for Iranian adolescents. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammadinia L, Ardalan A, Khorasani-Zavareh D, Ebadi A, Malek-Afzali H, Fazel M. The resilient child indicators in natural disasters: A systematic review protocol. Health Emerg Disasters Q. 2017;2:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child. UNICEF. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute Joanna Briggs. Adelaide: JBI; 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 08]. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 Edition. Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_ Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Dev Psychopathol. 1990;2:425–44. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, van der Horst H, Jadad AR, Kromhout D, et al. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grotberg EH. Resilience programs for children in disaster. Ambul Child Health. 2001;7:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guilera G, Pereda N, Paños A, Abad J. Assessing resilience in adolescence: The spanish adaptation of the adolescent resilience questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:100. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0259-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell P, Borchard C. Mainstreaming children's vulnerabilities and capacities into community-based adaptation to enhance impact. Clim Dev. 2014;6:372–81. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prince-Embury S, Saklofske DH. The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality. New York, US: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013. Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults: Translating research into practice. Resilience in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: Translating Research into Practice; pp. xvii–349. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ungar M. Practitioner review: Diagnosing childhood resilience – A systemic approach to the diagnosis of adaptation in adverse social and physical ecologies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:4–17. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandrova T, Kouteva M, Pashova L, Savova D, Marinova S, editors Conceptual framework for educational disaster centre save the children life. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. ISPRS Archives. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cumiskey L, Hoang T, Suzuki S, Pettigrew C, Herrgård MM. Youth participation at the third UN world conference on disaster risk reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2015;6:150–63. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaremohzzabieh Z, Samah BA. A review paper: The role of the internet in promoting youth well-being in flood-prone communities. Asian Soc Sci. 2013;9:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng EJ, Silverstein LB. China earthquake relief: Participatory action work with children. Sch Psychol Int. 2011;32:498–511. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu CY. Evaluating the Healing Power of Art and Play: A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Psychosocial Resilience in Child and Adolescent Survivors of the 2008 Sichuan, China Earthquake US: The Johns Hopkins U. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Milliano CW. Luctor et emergo, exploring contextual variance in factors that enable adolescent resilience to flooding. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015;14:168–78. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ratrin Hestyanti Y. Children survivors of the 2004 Tsunami in aceh, Indonesia: A study of resiliency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:303–7. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piangiamore GL, Musacchio G, Pino NA. Natural hazards revealed to children: the other side of prevention. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2015;419:171–81. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aitsi-Selmi A, Egawa S, Sasaki H, Wannous C, Murray V. The Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction: renewing the global commitment to people's resilience, health, and well-being. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2015;6:164–76. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kearney H. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction for Children. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masten AS. Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Dev Psychopathol. 2011;23:493–506. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massad S, Nieto FJ, Palta M, Smith M, Clark R, Thabet AA. Mental health of children in Palestinian kindergartens: Resilience and vulnerability. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2009;14:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson VA, Johnston DM, Ronan KR, Peace R. Evaluating children's learning of adaptive response capacities from shakeout, an earthquake and tsunami drill in two Washington state school districts. J Homel Secur Emerg Manag. 2014;11:347–73. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadeghi A. Education of Ready School: Tehran Disaster Mitigation and Management Organization. Tehran, Iran. 2015:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nazli A. “I’m healthy”: Construction of health in disability. Disabil Health J. 2012;5:233–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feitelberg SA. Response to Hurricane Ivan in Grand Cayman: Culture, Resilience, and Children US: Fielding Graduate U. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Exenberger S, Juen B. Well-being, Resilience and Quality of Life from Children's Perspectives: A Contextualized Approach. New York, US: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lueger-Schuster B, Ardino V. Helping children after mass disaster: Using a comprehensive trauma center and school support. Post-traumatic syndromes in childhood and adolescence: A handbook of reserech and practice. 2011:255–72. [Google Scholar]