Abstract

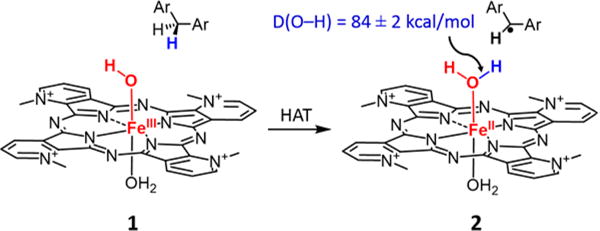

A reactive hydroxoferric porphyrazine complex, [(PyPz)FeIII(OH) (OH2)]4+ (1, PyPz = tetramethyl-2,3-pyridino porphyrazine), has been prepared via one-electron oxidation of the corresponding ferrous species [(PyPz)FeII(OH2)2]4+ (2). Electrochemical analysis revealed a pH-dependent and remarkably high FeIII–OH/FeII–OH2 reduction potential of 680 mV vs Ag/AgCl at pH 5.2. Nernstian behavior from pH 2 to pH 8 indicates a one-proton, one-electron interconversion throughout that range. The O–H bond dissociation energy of the FeII–OH2 complex was estimated to be 84 kcal mol−1. Accordingly, 1 reacts rapidly with a panel of substrates via C–H hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), reducing 1 to [(PyPz)FeII(OH2)2]4+ (2). The second-order rate constant for the reaction of [(PyPz)FeIII(OH) (OH2)]4+ with xanthene was 2.22 × 103 M−1 s−1, 5–6 orders of magnitude faster than other reported FeIII–OH complexes and faster than many ferryl complexes.

Nature has evolved a variety of remarkably efficient metalloenzymes for the selective oxygenation of even the most unreactive C–H bonds.1 Copper-containing particulate methane monooxygenases (pMMO), and the nonheme diiron enzymes sMMO and AlkB allow microorganisms to grow on natural gas and petroleum as their sole sources of carbon.2 Cytochrome P450s are thiolate-ligated heme proteins that use an oxoiron(IV)-porphyrin π-radical cation (compound I) as the active oxidant to functionalize substrates.3 Nonheme iron proteins such as TauD and SyrB2 break strong C–H bonds using a ferryl species, FeIV=O.4 By distinct contrast, lipoxygenases, which are widely distributed in plants, animals and fungi, employ hydroxoiron(III) or manganese(III) as reactive intermediates to activate allylic C–H bonds.5 These enzymes catalyze the regio- and stereospecific dioxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids to afford alkyl hydroperoxides. The use of enz-FeIII–OH as a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) agent to cleave the substrate C–H bond produces [enz-FeII–OH2 ·R]. This strategy avoids the formation of high-valent intermediates and facilitates oxygen capture by the incipient substrate radical, ·R.

Heme and nonheme oxoiron(IV) models have been extensively studied as hydrogen abstractors.4d,6 However, much less is known about the range of reactivity of hydroxometal(III) species, especially hydroxoiron(III). Notable early examples are hydroxoFeIII(PY5) complexes described by Stack et al.,7 and strongly hydrogen bonded terminal hydroxoiron(III) and manganese(III) species reported by Borovik et al.8 Mayer et al. have examined mechanisms of proton-coupled electron transfer with a hydroxoiron(III) porphyrin complex9 and recently, Tolman et al. have shown that a copper(III) hydroxide complex was highly reactive in C–H oxygenation reactions.10 An Fe(III) hydroxide complex described by Kovacs et al.11 is an unusually weak oxidant and Jackson et al. have described phenol oxidations by mononuclear MnIII–OH complexes.12 Yet, with the exception of the high-valent Cu(III)–OH complex, the reaction rates of hydrogen atom abstraction by these metal(III) hydroxide species are very slow compared with lipoxygenases.5f,13

We describe here the generation and reactions of a cationic hydroxoferric complex, [(PyPz)FeIII(OH) (OH2)]4+ (1, PyPz = tetramethyl-2,3-pyridino porphyrazine, Scheme 1) that is capable of fast hydrogen atom abstractions from substrates with moderate C–H bond energies (<85 kcal mol−1). The ferric complex is reduced to [(PyPz)FeII(OH2)2]4+ (2) for which an O–H BDE of 84 kcal mol−1 was estimated from the FeIII/FeII reduction potential. Second-order rate constants for C–H hydrogen atom abstraction by 1 are orders of magnitude faster than other reported ferric complexes.

Scheme 1.

Conversion of [(PyPz)FeIII(OH) (OH2)]4+ (1) to [(PyPz)FeII(OH2)2]4+ (2) via HAT

The ferrous complex 2 was prepared by heating pyridine-2,3-dicarboxylic acid with urea and ferrous chloride with ammonium heptamolybdate as a catalyst, followed by N-methylation with methyl p-toluenesulfonate as previously described.14 Complex 2 showed an appropriate molecular ion in the ESI MS (Figure S1) and sharp peaks in the 1H NMR with similar chemical shifts to those of ZnIIPyPz (Figure S2).15 The EPR spectrum of 2 showed no signals (Figure S3). On the basis of these results, air-stable complex 2 is formulated as a diamagnetic, low-spin ferrous complex [(PyPz)FeII(OH2)2]4+.16 Titration of 2, as monitored by UV–vis spectroscopy (Figure S4), showed two successive deprotonations of axial water with pKa1 = 8.0 and pKa2 = 10.1, indicative of diaqua, aqua-hydroxo and dihydroxo coordination of iron(II).6i,17

Cyclic voltammetry of 2 afforded a pH-dependent redox potential with a slope of −69 mV/pH in the Pourbaix diagram between pH 2.2 and 7.7 (Figure S5), close to the expected −59 mV/pH for ideal Nernstian behavior.11,18 Further, the Epa – Epc difference at pH 2.2 decreased as the scan rate decreased, with a ΔE of 68 mV at 2 mV/s (Figure S6 and Table S1). This behavior is indicative of the transfer one proton per electron and that the ferric complex 1 has one hydroxo and one aqua axial ligand over this entire pH range. The redox potential of Fe(III/II)PyPz is 680 mV vs Ag/AgCl at pH 5.2, unusually high for a FeIII/FeII couple, explaining the stability of 2 in air.

The ferrous complex 2 could be oxidized to complex 1 either by bulk electrolysis at 1 V (vs Ag/AgCl) or by adding one equivalent of t-butyl hydroperoxide, as monitored by UV–vis spectroscopy at pH 2.2 (Figure S7). The EPR spectrum of complex 1 (g = 2.49, 2.21, 1.89) indicates that 1 can be formulated as a low-spin ferric complex [(PyPz)FeIII(OH) (OH2)]4+ (Figure S3).19

The strength of the O–H bond in transition metal complexes is of considerable importance in determining the driving force for hydrogen atom abstraction.20 Because the redox potential of 1/2 is pH-dependent, the D(O–H) of 2 could be calculated using the modified form of the Bordwell eq (eq 1):

| (1) |

where E1/2 is the oxidation potential of 2 (referenced to NHE, Ag/AgCl + 220 mV) at a given pH and C is the solvent-dependent energy of formation and solvation of H in H2O, which equals to 55.8 kcal mol−1.20b,21 With the exceptionally high FeIII/FeII redox potential of the 1/2 couple, D(O–H) in 2 is calculated to be 84 ± 2 kcal mol−1, suggesting that 1 should be capable of oxidizing C–H substrates with moderate C–H bond strengths.

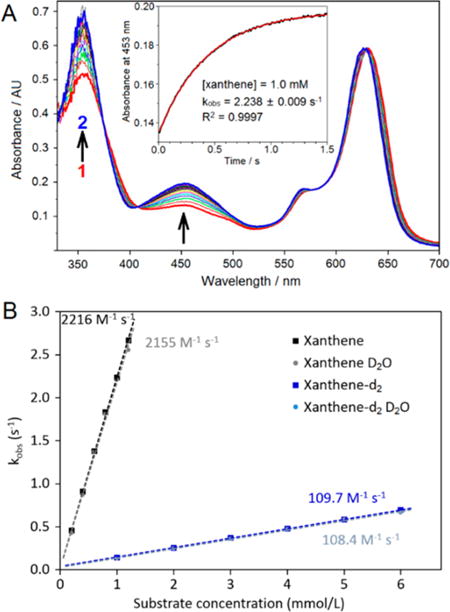

Indeed, the decay of (PyPz)FeIII–OH to (PyPz)FeII–OH2 was greatly accelerated by added substrates. The kinetics monitored at 453 nm by stopped-flow spectrophotometry for a panel of C–H substrates were very well fit by single exponentials over a range of substrate concentrations as expected for a pseudo-first order reduction of 1 to 2 (Figure 1). The second-order rate constant for xanthene oxidation was remarkably fast; k = 2216 ± 28 M−1 s−1. For xanthene-d2, the value was 109.7 ± 0.6 M−1 s−1, indicative of a very large substrate kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 20.2 ± 0.3. Clearly, cleavage of the C–H bond is the rate-determining step. Conversely, the solvent isotope effect was negligible (Figure 1B).6h

Figure 1.

(A) Single-mixing, stopped-flow UV–vis spectra obtained upon mixing 1.0 mM xanthene with 70 μM (PyPz)FeIII–OH (1) in 50:50 (v/v) 6 mM HClO4 water/acetonitrile solution (pH 2.2) at 20.0 °C over 1.5 s. Inset: changes in absorbance at 453 nm vs time (black line). Single exponential fitting (red line) resulted in a pseudo-first-order rate constant of 2.238 ± 0.009 s−1 (R2 = 0.9997). (B) Observed pseudo-first-order rate constants plotted vs xanthene concentration: xanthene in H2O: 2216 ± 28 M−1 s−1 (R2 = 0.9992) (black). Xanthene-d2 in H2O: 109.7 ± 0.6 M−1 s−1 (R2 = 0.9998), substrate KIE = 20.2 ± 0.3 (blue). Xanthene in D2O: 2155 ± 62 M−1 s−1 (R2 = 0.996), solvent KIE = 1.03 ± 0.04 (gray). Xanthene-d2 in D2O: 108.4 ± 2.8 M−1 s−1 (R2 = 0.997), combined substrate-solvent KIE = 20.4 ± 0.6 (light blue).

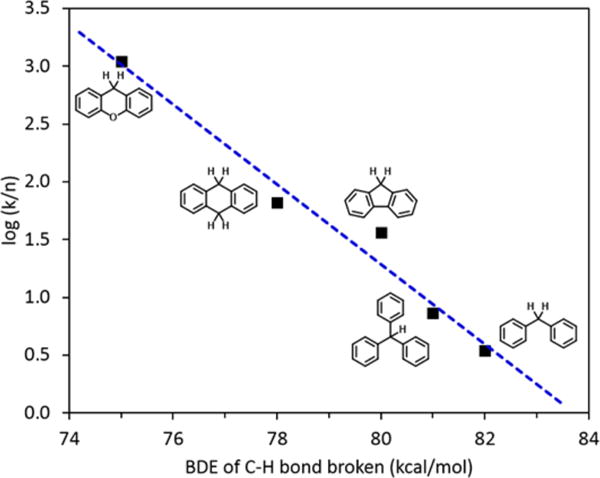

A correlation of the reduction of 1 by a panel of five substrates is plotted versus the C–H BDE in Figure 2. A linear Brønsted–Evans–Polanyi (BEP) relationship was found with a slope of −0.35, indicating a homolytic hydrogen atom transfer with an early transition state.6e,20c,22 Similar results were obtained in phosphate buffer/acetonitrile solution at both acidic (Figure S8–12) and near-neutral pH (Figure S13–15), with very little pH sensitivity up to pH 7.2 (Figure S16).

Figure 2.

Plot of log(k/n) vs substrate BDE, where k is the second-order rate constant and n is the number of equivalent C–H bonds that are broken in the reaction. Conditions: T = 20.0 °C, 50:50 (v/v) 6 mM HClO4 water/acetonitrile solution (pH 2.2). Slope = −0.35 ± 0.04 (R2 = 0.961).

The reaction of (PyPz)FeIII–OH with xanthene was examined in greater detail. A KIE of 20.2 at 293 K is significantly greater than the semiclassical limit of 7. Analyzing Arrhenius plots for xanthene and xanthene-d2 oxidation by 1 gave Ea(D) – Ea(H) = 2.5 ± 0.4 kcal mol−1 and A(H)/A(D) = 0.28 ± 0.14 (Figure S17). These results meet all three Kreevoy criteria for hydrogen tunneling: a KIE significantly larger than 6.4 at 20 °C; an activation energy difference greater than 1.2 kcal mol−1; and a ratio of pre-exponential factors less than 0.7.23 This large KIE of 20.2 is much greater than those reported for other synthetic ferric hydroxide complexes, and closer to the colossal KIE of ~80 found for lipoxygenases.7d,24

An Eyring analysis of the temperature dependence of the rate constants gave remarkably small enthalpies of activation; ΔH‡ = 6.1 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 and ΔS‡ = −23.7 ± 1.1 cal mol−1 K−1 for xanthene and ΔH‡ = 6.8 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1, ΔS‡ = −27.2 ± 0.8 cal mol−1 K−1 for 9,10-dihydroanthracene (DHA) (Figure S18). Accordingly, C–H scission occurs under entropy control with TΔS‡ > ΔH‡. Notably, the enthalpy barrier for lipoxygenase is only 2 kcal mol−1, resulting in the very fast rate of the enzyme.25

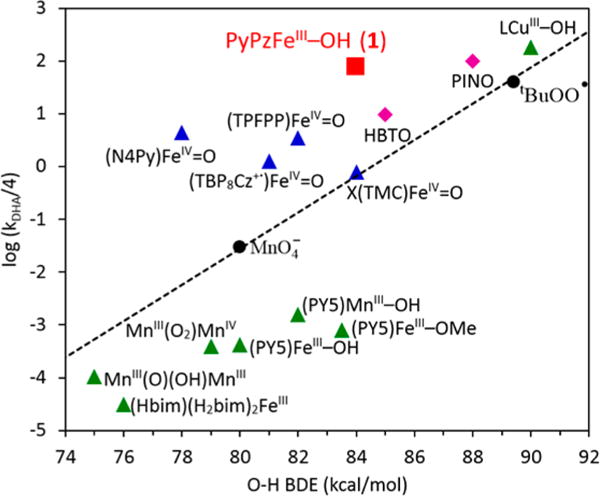

The unusually high reactivity of this hydroxoferric porphyrazine complex (1) prompts a comparison of C–H bond cleavage rates with other hydroxometal(III) and oxoiron(IV) complexes, as well as organic radicals. Figure 3 shows such a comparison for DHA oxidation at 25 °C by various complexes versus the D(O–H) values associated with the oxidants.6a,c,h,k,7,10a,b,18,26 For calibration, the dashed line passes through rates with known D(O–H) for permanganate, the t-butylperoxyl radical and the t-butoxyl radical (not shown).26a–d,27 Although the O–H BDE associated with 1/2 is only a few kcal mol−1 stronger than other synthetic hydroxo-manganese(III) and iron(III) complexes, the rate of 1/2 is 5 to 6 orders of magnitude faster. Moreover, this rate is 50–100-fold faster than typical ferryl complexes and comparable to that of the PINO radical, t-butylperoxy radical and a hydroxocopper(III) complex.10b,26e Much faster rates of DHA oxidation have been reported for oxoiron(IV) porphyrin cation radicals6e,h and for a high-spin ferryl species.26j

Figure 3.

Plot of log k for DHA oxidation and the O–H BDE formed by a variety of oxidants at 298 K. Rates were either measured directly or extrapolated to this temperature from experimentally determined activation parameters (Table S2). The black dashed line was drawn through the points of two oxygen radicals and permanganate as a reference. The red square is (PyPz)FeIII–OH (1). Green triangles are reported metal(III) complexes. Blue triangles are reported Fe(IV)=O complexes. Magenta diamonds are organic oxy-radicals. An N–H bond is formed instead of O–H bond in FeIII(Hbim)(H2bim)2. Data points of HBTO and PINO radicals are estimated from fluorene oxidation rates.

What factors contribute to the high HAT reactivity of (PyPz)FeIII–OH (1)? Certainly, part of the acceleration derives from the unusually high FeIII/FeII redox potential. We note that the FeIV–OH (compound II) of the heme-thiolate peroxygenase APO is also highly reactive toward C–H bond scission despite its modest (0.84 V vs NHE) reduction potential.6i On the other hand, oxoFeIV-4-TMPyP, a cationic porphyrin similar to 1 with four methylpyridinium positive charges, oxidizes xanthene at a rate more than 1 order of magnitude slower than the hydroxoferric species 1.28 A small reorganization energy for reduction of 1 to 2 might derive from the low-spin configuration of both species and the rather rigid porphyrazine ring system. The significant hydrogen tunneling contributes a factor of ∼3. These factors suggest that some iron hydroxides may have intrinsically lower reorganization energies than corresponding ferryl species, reflecting less drastic bond-order changes. The possibility of a disproportionation of the ferric complex 1 to generate a reactive ferryl species is highly unlikely given the near-perfect fit of the kinetic data to a single exponential (R2 = 0.9997) over six half-lives of reaction and the tight isosbestic point at 407 nm (Figure 1A). Disproportionation processes should be second-order in FeIII–OH (Figure S19).

In summary, we have found that the hydroxoferric porphyrazine complex, [(PyPz)FeIII(OH) (OH2)]4+ (1), is unusually reactive toward hydrogen abstraction from benzylic C–H substrates. The reactions occur through a hydrogen atom transfer mechanism, which is supported by the large KIE and a linear relationship between substrate C–H BDE and log k. A (PyPz)FeII–OH2 O–H BDE of 84 kcal mol−1 is estimated from the redox potential of (PyPz)FeIII–OH/(PyPz)FeII–OH2 and the pKa of the axial aqua ligand of (PyPz)FeII. The shallow BEP slope (−0.35) indicates an early transition state for C–H scission and the low activation enthalpies (ΔH‡ = 6.1–6.8 kcal/mol) show that the reaction is entropy controlled (TΔS‡ > ΔH‡), suggesting a small reorganization energy for this process. These findings provide new insights into the reactivity of FeIII–OH species and suggest that M–OH oxidants may have untapped potential in the context of C–H activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support of this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (2R37 GM036298).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b13091.

UV–vis and NMR spectra spectra, stopped-flow transients, kinetic traces and electrochemical data (PDF)

ORCID

John T. Groves: 0000-0002-9944-5899

Notes

The autho fn-type="conflict"rs declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Huang X, Groves JT. JBIC, J Biol Inorg Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Lipscomb JD. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Citek C, Gary JB, Wasinger EC, Stack TD. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6991. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lieberman RL, Rosenzweig AC. Nature. 2005;434:177. doi: 10.1038/nature03311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tinberg CE, Lippard SJ. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:280. doi: 10.1021/ar1001473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Cooper HLR, Mishra G, Huang X, Pender-Cudlip M, Austin RN, Shanklin J, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20365. doi: 10.1021/ja3059149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ortiz de Montellano PR. Chem Rev. 2010;110:932. doi: 10.1021/cr9002193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shaik S, Cohen S, Wang Y, Chen H, Kumar D, Thiel W. Chem Rev. 2010;110:949. doi: 10.1021/cr900121s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yosca TH, Rittle J, Krest CM, Onderko EL, Silakov A, Calixto JC, Behan RK, Green MT. Science. 2013;342:825. doi: 10.1126/science.1244373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Groves JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Groves JT. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:434. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Krest CM, Silakov A, Rittle J, Yosca TH, Onderko EL, Calixto JC, Green MT. Nat Chem. 2015;7:696. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Rittle J, Green MT. Science. 2010;330:933. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Groves JT. Nat Chem. 2014;6:89. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Price JC, Barr EW, Tirupati B, Bollinger JM, Krebs C. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7497. doi: 10.1021/bi030011f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blasiak LC, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT, Drennan CL. Nature. 2006;440:368. doi: 10.1038/nature04544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Galonić Fujimori D, Barr EW, Matthews ML, Koch GM, Yonce JR, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM, Krebs C, Riggs-Gelasco PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13408. doi: 10.1021/ja076454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Biswas AN, Puri M, Meier KK, Oloo WN, Rohde GT, Bominaar EL, Münck E, Que L. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2428. doi: 10.1021/ja511757j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Collazo L, Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:9052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.709154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wennman A, Oliw EH, Karkehabadi S, Chen Y. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.707380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Samuelsson B, Dahlen S, Lindgren J, Rouzer C, Serhan C. Science. 1987;237:1171. doi: 10.1126/science.2820055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Boyington J, Gaffney B, Amzel L. Science. 1993;260:1482. doi: 10.1126/science.8502991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Su C, Oliw EH. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Knapp MJ, Klinman JP. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11466. doi: 10.1021/bi0300884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Kaizer J, Klinker EJ, Oh NY, Rohde JU, Song WJ, Stubna A, Kim J, Münck E, Nam W, Que L. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:472. doi: 10.1021/ja037288n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jackson TA, Rohde JU, Seo MS, Sastri CV, DeHont R, Stubna A, Ohta T, Kitagawa T, Münck E, Nam W, Que L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12394. doi: 10.1021/ja8022576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cho K, Leeladee P, McGown AJ, DeBeer S, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7392. doi: 10.1021/ja3018658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen Z, Yin G. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:1083. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00244j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bell SR, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9640. doi: 10.1021/ja903394s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang X, Peter S, Kinne M, Hofrichter M, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12897. doi: 10.1021/ja3049223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Wang X, Peter S, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Groves JT. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:9238. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Boaz NC, Bell SR, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2875. doi: 10.1021/ja508759t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Wang X, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Groves JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503340112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Usharani D, Lacy DC, Borovik AS, Shaik S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17090. doi: 10.1021/ja408073m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Jeong YJ, Kang Y, Han AR, Lee YM, Kotani H, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:7321. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Jonas RT, Stack TDP. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8566. [Google Scholar]; (b) Goldsmith CR, Jonas RT, Stack TDP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:83. doi: 10.1021/ja016451g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Goldsmith CR, Cole AP, Stack TDP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9904. doi: 10.1021/ja039283w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Goldsmith CR, Stack TDP. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:6048. doi: 10.1021/ic060621e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Cook SA, Borovik AS. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2407. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gupta R, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13234. doi: 10.1021/ja030149l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gupta R, Taguchi T, Borovik AS, Hendrich MP. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:12568. doi: 10.1021/ic401681r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter TR, Mayer JM. Chem Sci. 2014;5:372. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52055B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Donoghue PJ, Tehranchi J, Cramer CJ, Sarangi R, Solomon EI, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17602. doi: 10.1021/ja207882h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dhar D, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1322. doi: 10.1021/ja512014z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dhar D, Yee GM, Spaeth AD, Boyce DW, Zhang H, Dereli B, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:356. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brines LM, Coggins MK, Poon PCY, Toledo S, Kaminsky W, Kirk ML, Kovacs JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2253. doi: 10.1021/ja5068405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Wijeratne GB, Corzine B, Day VW, Jackson TA. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:7622. doi: 10.1021/ic500943k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wijeratne GB, Day VW, Jackson TA. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:3295. doi: 10.1039/c4dt03546a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rice DB, Wijeratne GB, Burr AD, Parham JD, Day VW, Jackson TA. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:8110. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knapp MJ, Seebeck FP, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2931. doi: 10.1021/ja003855k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safari N, Jamaat PR, Shirvan SA, Shoghpour S, Ebadi A, Darvishi M, Shaabani A. J Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2005;09:256. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wohrle D, Gitzel J, Okura I, Aono S. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 1985;1171 [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Appleby AJ, Fleisch J, Savy M. J Catal. 1976;44:281. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ercolani C, Gardini M, Murray KS, Pennesi G, Rossi G. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:3972. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tanaka AA, Fierro C, Scherson D, Yaeger EB. J Phys Chem. 1987;91:3799. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dieing R, Schmid G, Witke E, Feucht C, Dreßen M, Pohmer J, Hanack M. Chem Ber. 1995;128:589. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Ferrer-Sueta G, Vitturi D, Batinić-Haberle I, Fridovich I, Goldstein S, Czapski G, Radi R. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lahaye D, Groves JT. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1786. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang D, Zhang M, Bühlmann P, Que L. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7638. doi: 10.1021/ja909923w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Groves JT, Quinn R, McMurry TJ, Lang G, Boso B. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1984:1455. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi N, Shirai H, Hojo N. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1984:2107. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ukita S, Fujii T, Hira D, Nishiyama T, Kawase T, Migita CT, Furukawa K. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:61. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Roth JP, Yoder JC, Won TJ, Mayer JM. Science. 2001;294:2524. doi: 10.1126/science.1066130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6961. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mayer JM. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:36. doi: 10.1021/ar100093z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bordwell FG. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:456. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Evans MG, Polanyi M. Trans Faraday Soc. 1938;34:11. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mayer JM. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:441. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Kwart H. Acc Chem Res. 1982;15:401. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim Y, Kreevoy MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:7116. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lewandowska-Andralojc A, Grills DC, Zhang J, Bullock RM, Miyazawa A, Kawanishi Y, Fujita E. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3572. doi: 10.1021/ja4123076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Cowley RE, Eckert NA, Vaddadi S, Figg TM, Cundari TR, Holland PL. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9796. doi: 10.1021/ja2005303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Carr CAM, Klinman JP. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2212. doi: 10.1021/bi500070q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu S, Sharma SC, Scouras AD, Soudackov AV, Carr CAM, Hammes-Schiffer S, Alber T, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:8157. doi: 10.1021/ja502726s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Layfield JP, Hammes-Schiffer S. Chem Rev. 2014;114:3466. doi: 10.1021/cr400400p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Jonsson T, Glickman MH, Sun S, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:10319. [Google Scholar]; (b) Knapp MJ, Rickert K, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3865. doi: 10.1021/ja012205t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Arends IWCE, Mulder P, Clark KB, Wayner DDM. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:8182. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gardner KA, Kuehnert LL, Mayer JM. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:2069. doi: 10.1021/ic961297y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang K, Mayer JM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1470. [Google Scholar]; (d) Roth JP, Mayer JM. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:2760. doi: 10.1021/ic990251c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Koshino N, Saha B, Espenson JH. J Org Chem. 2003;68:9364. doi: 10.1021/jo0348017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Brandi P, Galli C, Gentili P. J Org Chem. 2005;70:9521. doi: 10.1021/jo051615n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Sastri CV, Lee J, Oh K, Lee YJ, Lee J, Jackson TA, Ray K, Hirao H, Shin W, Halfen JA, Kim J, Que L, Shaik S, Nam W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709471104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Fertinger C, Hessenauer-Ilicheva N, Franke A, van Eldik R. Chem - Eur J. 2009;15:13435. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) England J, Martinho M, Farquhar ER, Frisch JR, Bominaar EL, Münck E, Que L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:3622. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Puri M, Biswas AN, Fan R, Guo Y, Que L. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2484. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.We have used BDE values instead of BDFE to facilitate comparisons with other systems. Entropic effects due to electronic reorganization should be small because both 1 and 2 are low-spin. The aqueous BDFE for 2 would be ~2 kcal/mol larger, reflecting the difference between CH and CG in eq 1 (cf. references 10c, 11 and 20b).

- 28.Bell SR. PhD Thesis. Princeton University; Princeton, NJ: 2010. Modeling Heme Monoxygenases with Water-Soluble Iron Porphyrins. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.