Abstract

Complete tumor removal during surgery has a great impact on patient survival. To that end, the surgeon should detect the tumor, remove it and validate that there are no residual cancer cells left behind. Residual cells at the incision margin of the tissue removed during surgery are associated with tumor recurrence and poor prognosis for the patient. In order to remove the tumor tissue completely with minimal collateral damage to healthy tissue, there is a need for diagnostic tools that will differentiate between the tumor and its normal surroundings.

Methods: We designed, synthesized and characterized three novel polymeric Turn-ON probes that will be activated at the tumor site by cysteine cathepsins that are highly expressed in multiple tumor types. Utilizing orthotopic breast cancer and melanoma models, which spontaneously metastasize to the brain, we studied the kinetics of our polymeric Turn-ON nano-probes.

Results: To date, numerous low molecular weight cathepsin-sensitive substrates have been reported, however, most of them suffer from rapid clearance and reduced signal shortly after administration. Here, we show an improved tumor-to-background ratio upon activation of our Turn-ON probes by cathepsins. The signal obtained from the tumor was stable and delineated the tumor boundaries during the whole surgical procedure, enabling accurate resection.

Conclusions: Our findings show that the control groups of tumor-bearing mice, which underwent either standard surgery under white light only or under the fluorescence guidance of the commercially-available imaging agents ProSense® 680 or 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), survived for less time and suffered from tumor recurrence earlier than the group that underwent image-guided surgery (IGS) using our Turn-ON probes. Our "smart" polymeric probes can potentially assist surgeons' decision in real-time during surgery regarding the tumor margins needed to be removed, leading to improved patient outcome.

Keywords: precision nanomedicine, polymers, PGA, HPMA copolymer, theranostics, molecular imaging, NIR fluorescence, image-guided surgery

Introduction

When cancer is diagnosed in its early stages, before metastatic spread, the primary treatment is surgical resection. The complete removal of the primary tumor is one of the most important factors in improving patient outcome. If cancer cells are detected in the surrounding tissue excised during surgery, it is considered a “positive tumor margin”, which is associated with poor prognosis, higher rates of recurrence and lower survival rates in various cancer types 1-8. Maneuvering between the two edges of damaging healthy tissues 9 and leaving residual disease is the main challenge during tumor resection that could certainly benefit from relying on more than the surgeon's naked eye. Image-guided surgery (IGS) has recently emerged as a complementary imaging technique to white light, supplying the surgeon an essential tool for the important goals mentioned above. The area of IGS has evolved rapidly during the last two decades, as reflected by the various imaging agents for different modalities, such as diffuse tensor imaging (DTI) and functional MRI (fMRI), that function as diagnostics before surgery to locate the tumor in relation to functional regions, and during surgery in order to assess the tumor margins 10-15. However, these modalities lack the possibility of using targeted contrast agents to specifically visualize certain enzymes that are highly active at the tumor site, thus enabling better differentiation of cancerous from healthy tissue. In addition, intraoperative systems are costly and complex 16.

Intraoperative fluorescence imaging offers the benefits of high contrast and sensitivity, low cost, ease of use, safety, and visualization of cells and tissues both in vitro and in vivo 17, 18. Over the past several years, a vast amount of published data showed improved visualization of cancer tissue over dark background by the utilization of different fluorescent probes. One example of a clinically evaluated fluorescent “Always ON” low molecular weight (MW) probe includes a folate receptor-targeted fluorophore 19. The current challenge of near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF)-guided surgery is to design probes with high selectivity for tumors and clear visualization. To that end, different fluorescent probes have been developed and studied; these are often referred to as “smart” probes. “Smart” probes are activated at the tumor site while otherwise they remain intact. Thus, in comparison to the “Always ON” probes, minimal signal is emitted, and the background noise is reduced, leading to an improved signal-to-noise ratio and clearer visualization. The activation and signal enhancement can occur via different triggers or peptide linkers recognized by certain enzymes or analytes that are overexpressed in the tumor and its surroundings. Recently reported Turn-ON probes include fluorescently-tagged activatable cell-penetrating peptides (ACPP) 20, low MW fluorogenic peptides, and trigger-activated analytes 21-25. The ideal fluorescent probe for intra-operative application should possess high tumor selectivity and enhanced accumulation while sparing the healthy tissue, thus delineating tumor margins in real-time during the entire surgical procedure.

Different low MW molecules used in clinical practice suffer from several drawbacks. Indocyanine green (ICG), a non-specific, low MW, clinically approved near-infrared (NIR) fluorophore, possesses a very short plasma half-life of about 2-4 min, followed by a slower clearance rate after binding to plasma proteins 26. This, in turns, limits its application for prolonged procedures that require tumor accumulation and detection during image-guided surgery. The FDA-approved 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), a protoporphyrin precursor, generates a fluorescence signal upon cellular metabolism. However, its broad usage is limited due to insufficient accumulation inside tumor cells 27, 28. Nevertheless, many proof-of-principle clinical trials have been conducted in several types of surgeries with ICG and 5-ALA fluorophores 16. Other reports of activatable Turn-ON probes include numerous low MW cathepsins-sensitive substrates, most of which show fast clearance. As a result, shortly after administration, their signal is greatly reduced 18.

Polymeric systems hold great potential in improving the performance of imaging agents, as they do for drugs 29. A macromolecular carrier can alter the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of the dye. While a nanoscale carrier does not extravasate more than small molecules from normal vessels, it can preferentially extravasate into the tumor site because of the tumor leaky vessels, and be retained there due to the poor lymphatic drainage. This phenomenon is termed the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect 30. We and other groups have shown that the signal obtained from the tumor is greater and is retained for a longer time for macromolecular probes compared with that of low MW fluorescent molecules 22, 31, 32. The general concept of an activated Turn-ON polymeric or macromolecular probe generating a fluorescence signal was previously proposed 33; however, there have been many unique reports on different systems 34, 35, mechanisms of activation and/or versatile applications 36-38. Several quantum dots have also shown benefits in the fluorescence image-guided surgery arena, including bladder cancer resection 35, small MW integrin-targeted RGD probes for colorectal cancer and ureters 39 and fluorescently-tagged targeted antibodies for head-and-neck cancer 34.

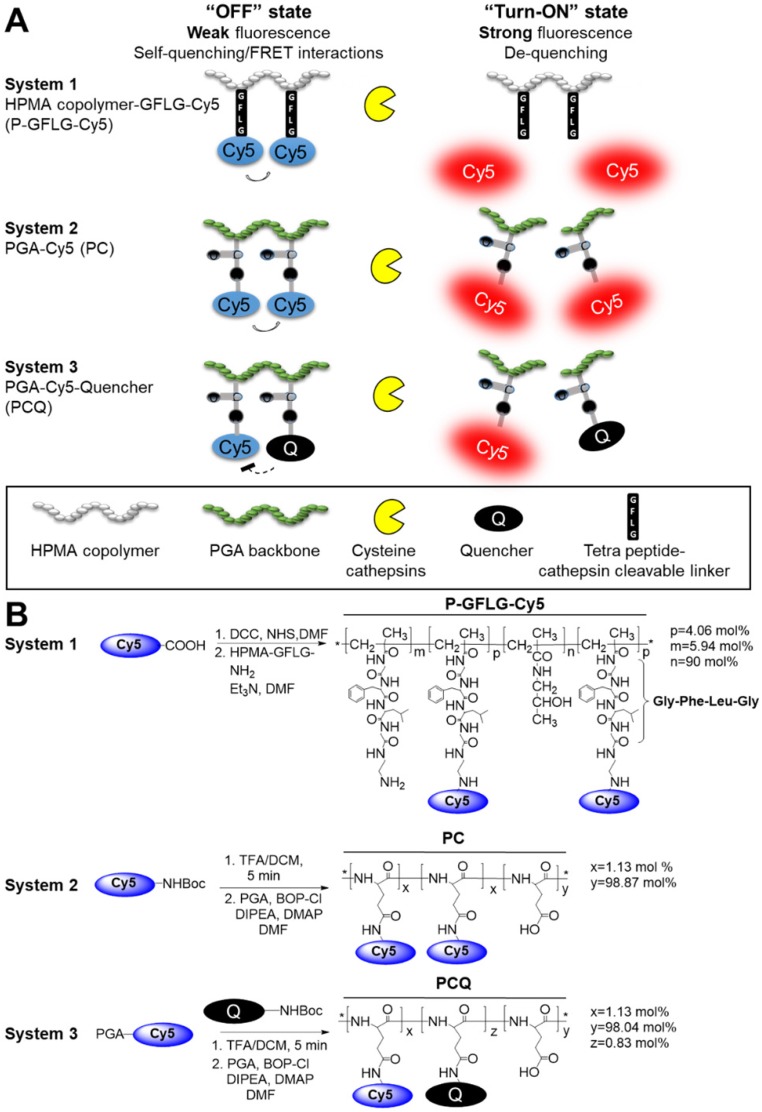

Reinforcement to this strategy of macromolecule conjugation with imaging agents is given by nanoparticle- or polymer-based imaging probes that are under clinical evaluation or recently gained FDA approval. Examples include the FDA-approved Lymphoseek®, a technetium 99mTc-dextran conjugate for sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) identification that has shown persistent SLN accumulation for at least 24 h 40, a polyethyleneglycol-bound (PEGylated) protease activatable fluorescent probe that is in a phase 1 clinical trial 41 and an 124I-cRGDY-PEGylated core-shell silica nanoparticle 42. Cysteine cathepsins play a pivotal role in the tumor and its surroundings, and may assist its progression. It has been reported that many tumor types have overexpressed activated cathepsins 43, 44. This property can be exploited to rationally design smart probes that can be triggered at the tumor site. In this study, we report the design, synthesis and characterization of three polymeric Turn-ON probes that are activated by cathepsin enzymatic degradation to generate a fluorescence signal. These Turn-ON probes possess unique properties, resulting from different structures and activation modes for the application of image-guided surgery proposed herein, which differentiate them from previously reported probes. The first polymeric Turn-ON probe (system 1) was recently reported by us 31 and composed of the non-degradable N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer backbone bearing self-quenched (homo-FRET) NIRF Cy5 dyes. Two additional novel polymeric systems (2 and 3) are composed of a biodegradable poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA) polymeric backbone loaded with self-quenched Cy5 molecules (system 2) or hetero-FRET-quenched Cy5 and dark quencher moieties (system 3) (Figure 1A). The systems utilize different mechanisms of activation: In system 1, enzymatic cleavage of the Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly (GFLG) tetrapeptide linker results in a release of the free dye while the polymeric backbone remains intact. In systems 2 and 3, the enzymes cleave the polymeric backbone of the poly-glutamic acid. Both mechanisms eventually release the free dyes, allowing them to emit their fluorescence and thus Turn-ON. We set to study the different mechanisms and sizes of the probes and how they affect their ability to serve as imaging agents for image-guided surgery. We characterized our conjugates for their hydrodynamic diameter, quenching properties, Turn-ON capacity and enzymatic efficiency upon incubation with cathepsin B (CTSB), one of the members of the cysteine cathepsins family. We chose to focus on the two leading probes that showed the greatest quenching and Turn-ON capacity for further in vivo evaluation as image-guided surgery agents. The in vitro and in vivo characterization of our Turn-ON probes was compared to that of “Always ON” (resulted from non-cleavable linker addition or lower loading of Cy5 molecules) and Never ON control probes. A schematic representation of these different control probes is shown in Scheme S1.

Figure 1.

Design and synthesis of self-quenched HPMA copolymer-GFLG-Cy5 (P-GFLG-Cy5), PGA-Cy5 (PC) and FRET-based PGA-Cy5-Quencher (PCQ) Turn-ON probes. (A) Schematic representation of two different pathways of the probes' degradation by cysteine cathepsins, leading to their activation and increase in the fluorescence signal, as the fluorophore molecules are distanced from each other and quenching is terminated. (B) Synthesis scheme of P-GFLG-Cy5 (System 1), PC (System 2) and PCQ (System 3) Turn-ON probes.

We set out to evaluate and study how the differences in size and mechanism of activation between our Turn-ON probes may affect their potential use as optical guiding tools during surgical resection of tumors.

Methods

Materials

HPMA copolymer-GFLG-ethylenediamine (HPMA-GFLG-NH2) incorporating 10 mol% of GFLG-NH2 was obtained from Polymer Laboratories (Church Stretton, UK). HPMA-GFLG-NH2 has a MW of 31,600 Da and a polydispersity (PDI) of 1.66. RPMI 1640, MEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, nystatin, L-glutamine, Hepes buffer, non-essential amino acids solution and sodium pyruvate were purchased from Biological Industries Ltd. (Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel). DMEM, Advanced DMEM and glutaMAX x100 solutions were purchased from Rhenium (Modiin, Israel). Cathepsin B (CTSB) enzyme from bovine spleen (CAS no# 9047-22-7) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Rehovot, Israel). Human recombinant cathepsin S (CTSS) (cat no# 1183-CY) and cathepsin L (CTSL) (cat no# 952-CY) were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, US). All other chemical reagents, including salts and solvents, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Rehovot, Israel). All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were performed under an Ar (g) atmosphere. Chemicals and solvents were either AR grade or purified by standard techniques.

Synthesis of HPMA copolymer-GFLG-Cy5 (P-GFLG-Cy5) conjugate

Cy5-COOH was synthesized as previously described 23. Next, Cy5-COOH fluorophore was conjugated with HPMA-GFLG-NH2 copolymer precursor in a two-step synthesis. First, Cy5-COOH (45 mg, 0.069 mmol) was dissolved in 0.7 mL anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (11.9 mg, 0.103 mmol) and N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) (21.332 mg, 0.103 mmol) were added in order to activate the free carboxylic group of the fluorophore for further coupling to the HPMA-GFLG-NH2 copolymer precursor. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature (RT) in the dark for 12 h. Then, HPMA-GFLG-NH2 copolymer precursor (100 mg, 0.573 mmol) was dissolved in 0.5 mL anhydrous DMF and added to the reaction mixture. The reaction progress was followed by high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (UltiMate® 3000 Nano LC systems, Dionex). At the end of the reaction, the solvent was removed partially by high vacuum and precipitated in cold ether. The precipitate was further washed with acetone and dried under vacuum. Purification of the conjugate by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed using an ÄKTA FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences) with Sephadex LH-20 columns in MeOH using a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and UV/Vis detection. In order to remove all excess of free fluorophore, the residue was dissolved in water and dialyzed for 1 day at 4 °C (MW cut-off (MWCO) 6-8 kDa) against DI water. The conjugate was isolated by freeze-drying. Cy5 loading was determined using SpectraMax M5e multi-detection reader. The absorbance of conjugated Cy5 was measured and compared to that of free Cy5. Quenching efficiency was expressed as a percentage of the fluorescence intensity of the HPMA copolymer-GFLG-Cy5 (P-GFLG-Cy5) conjugate (λEm= 670 nm) compared with the emission of the free Cy5 at an equivalent concentration. MW theoretical value of the conjugate was determined according to HPMA-GFLG-NH2 copolymer precursor MW, and Cy5 molecules loading (13.2 weight percent (wt%), 4.06 mol%). 1H NMR and HPLC characterizations are presented in Figure S1 and Figure S3.

Synthesis of PGA-Cy5 (PC) conjugate

Poly-L-α-glutamic acid (PGA) was synthesized as previously described 45 by ring opening polymerization that started from α-N-carboxyanhydrides (NCA) of a γ-benzyl-L-glutamate preparation. Neopentyl-NH3BF4 was used as an initiator. The PGA polymer obtained had a MW of 9959 and PDI of 1.166, as characterized by multi-angle static light scattering (MALS) described later in this section. Cy5-NHBoc and dark quencher, Q-NHBoc, were conjugated directly to a PGA backbone in two similar coupling reactions. In order to activate the fluorophore, tert-butyloxycarbonyl protecting group (Boc) was removed from the reactive amine by mixing Cy5-NHBoc (15.5 mg, 0.0194 mmol) with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and dichloromethane (DCM) mixture (1:1) for 5 min following immediate high-vacuum evaporation. Next, PGA (25 mg, 0.194 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and then transferred into the flask containing Cy5-NH2. Bis (2-oxo-3-oxazolidinyl) phosphinic chloride (BOP-Cl) (9.867 mg, 0.0388 mmol) was dissolved in 500 µL anhydrous DMF, and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (5.681 mg, 0.0465 mmol) dissolved in 500 µL anhydrous DMF were added to the reaction mixture in order to activate the carboxylic acid residues on the PGA. Finally N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (5 µL, 0.0155 mmol) was added. The reaction was mixed for 4 h in an ice bath, and then the ice was removed and the reaction continued at RT for an additional 48 h under argon (Ar(g)) atmosphere. The reaction progress was followed by thin layer chromatography (TLC). At the end, 3 mL of 10% sodium chloride solution (NaCl) was added and the mixture was acidified to pH 2.5 by addition of 0.5 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution. The reaction was stirred for 1 h at RT and then the solvent was removed by high vacuum. The obtained solid was washed three times with acetone-chloroform (4:1) mixture, salted in 0.25 M sodium bicarbonate solution (NaHCO3) and dialyzed against DI water for 48 h at 4 °C (MWCO 3.5 kDa). Final purification of the conjugate by SEC was performed using an ÄKTA FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences) using HiTrap desalting columns (Sephadex G-25 Superfine) in DDW with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min; UV/Vis detection was monitored at 220, 600 and 650 nm. The conjugate was dried by freeze-drying and characterized by HPLC (UltiMate® 3000 Nano LC systems, Dionex). Cy5 loading and quenching efficiency were determined as described above. MW theoretical value of the conjugate was determined according to PGA polymeric precursor MW, and Cy5 loading (5.7 wt%, 1.13 mol%). 1H NMR characterizations are presented in Figure S2.

Synthesis of PGA-Cy5-Quencher (PCQ) conjugate

Next, the obtained PC conjugate was coupled with an aminated dark quencher (Q-NHBoc) 23, in a similar procedure as described above. Briefly, Q-NHBoc (15 mg, 0.0075 mmol) was deprotected, dried under vacuum and then the Q-NH2 was re-dissolved in anhydrous DMF. PC (15 mg, 0.075 mmol) was added to the reaction and stirred. BOP-Cl (3.818 mg, 0.015 mmol) and DMAP (2.749 mg, 0.0225 mmol) dissolved as above in anhydrous DMF and were added to the reaction mixture and finally, DIPEA (5 µL, 0.0155 mmol) was added. The reaction was mixed for 4 h in an ice bath, and then for an additional 48 h at RT under Ar(g) atmosphere. The reaction progress was followed by HPLC. At the end, as described above, NaCl was added, the mixture was acidified and stirred for 1 h at RT followed by solvent removal under high vacuum. The obtained solid was washed with acetone-chloroform mixture, salted in NaHCO3 solution and dialyzed against DI water for 48 h at 4 °C (MWCO 3.5 kDa), as described above. Final purification of the conjugate by SEC was performed as described above followed by freeze-drying of the conjugate and HPLC characterization. The loading of the conjugated quencher molecules was determined using SpectraMax M5e multi-detection reader. The absorbance of conjugated quencher was measured and compared to that of free quencher. Quenching efficiency of the final conjugate was expressed as a percentage of the fluorescence intensity of the PGA-Cy5-Quencher (PCQ) (λEm = 670 nm) compared with the emission of free Cy5 at an equivalent concentration. The theoretical MW of the conjugate was determined according to PGA polymeric precursor MW, Cy5 and quencher loading ((5.7 wt%, 1.13 mol%) and (4.1 wt%, 0.83 mol%), respectively). HPLC characterization is presented in Figure S3.

Multi-angle static light scattering (MALS)

MW and PDI analysis of the PGA polymer were performed on an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies Santa Clara, CA, US) equipped with a multi-angle light scattering detector (Wyatt Technology Corporation Santa Barbara, US), using Shodex Kw404-4F column (Showa Denko America, Inc.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

P-GFLG-Cy5 (1 mg/mL in saline) was adsorbed on formvar/carbon-coated grids and stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (negative staining). TEM images were taken using a JEM 1200EX TEM (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Diameters were measured by measureIT software; the particle distribution is the average of 3 fields of view, 10 particles per field.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

PC (0.01 mg/mL in DDW) and PCQ (0.1 mg/mL in DDW) samples were dropped on a silicon wafer and blotted with cellulose paper. SEM images were taken using a Quanta 200 FEG Environmental SEM (FEI, Oregon, USA) at high vacuum and 5.0 kV. Diameters were measured by measureIT software; the particle distribution is the average of 3 fields of view, 20 particles per field.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis

The mean hydrodynamic diameter of the PC conjugate was measured using a DynaPro Plate Reader II instrument at an 830 nm laser wavelength (Wyatt Technology Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA 93117 USA). The mean hydrodynamic diameter of the P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ conjugates was measured using a Möbius instrument at a 540 nm laser wavelength using a 532 nm longpass filter (Wyatt Technology Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA 93117 USA). P-GFLG-Cy5, PC and PCQ samples were prepared by dissolving 0.5, 1 and 1 mg/mL of polymer conjugates in saline, DDW and DDW, respectively. All measurements were performed at 25 °C.

Cathepsin B (CTSB) activity assay

Cy5 enzymatically directed release from the conjugates was studied in vitro. P-GFLG-Cy5, PC and PCQ conjugates (5 µM Cy5-eq. concentration) were incubated at 37 °C with CTSB (0.56 U/mL) in freshly prepared activity phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5) containing 0.05 M NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 5 mM reduced glutathione (GSH). For the controls, conjugates were incubated in the absence of CTSB or in the presence of CTSB inhibitor, CA-074 Me (100 µM), in the same conditions. The inhibitor concentration of 100 µM was chosen to inhibit 0.56 U/mL of CTSB. This ratio of about 200-fold was determined according to the inhibition concentration dependence evaluation. In this evaluation, inhibitor concentrations above 41.67 µM inhibited 0.2 U/mL of CTSB (about 200-fold of enzyme concentration over inhibitor concentration) (Figure S4E-F). Free Cy5 release was monitored by measuring the change in the fluorescence intensity at sequential time points. The fluorescence measurements were carried out using SpectraMax M5e multi-detection reader (λEx: 630 nm, λEm: 670 nm, filter: 665 nm). Samples (100 µL) were collected every 24 h (up to 70 h) and immediately analyzed.

In vitro enzyme kinetics of Turn-ON probes

CTSB enzyme (0.2 U/mL, pH 5.5) was challenged with increasing concentrations (triplicates of 0 to 60 µM Cy5-eq. concentration) of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ substrates. Turnover curves were followed by measuring the increase in Cy5 fluorescence (λEx: 630 nm, λEm: 670 nm, filter: 665 nm) using SpectraMax M5e multi-detection reader. The conversion from fluorescence to concentration of product formed was calculated according to a free Cy5 calibration curve. The initial velocity of the probe cleavage by CTSB was calculated from the linear portion of the curve of each Turn-ON probe concentration. The kinetic parameters (KM, Kcat and KM/Kcat) were obtained by fitting the experimental data to the Michaelis Menten equation, Vt = Vmax * [S] / (KM+ [S]), using GraFit 7.0 software.

Cell culture

Human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231 and MCF7, murine mammary 4T1, murine melanoma B16-F10 and human melanoma A375, WM115 and WM239A cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC Manassas, VA, USA). 131/4-5B1 human melanoma brain-metastasizing cell line was a kind gift from Prof. Robert Kerbel (University of Toronto, Canada) 46 and Ret-mCherry melanoma sorted (RMS) cells, derived from MT/Ret transgenic mice were provided by Dr. Viktor Umansky (DKFZ, Germany) and were transduced by us with mCherry as described previously 47. Murine melanoma D4M.3A cell line was kindly provided by Prof. David W. Mullins (Dartmouth College, Hanover). PD-MBM1, PD-MBM2 and PD-MBM3 cell lines isolated from patient-derived melanoma brain metastases were obtained from Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center under an approved IRB protocol. All cell lines were cultured in growing media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 12.5 IU/mL nystatin and 2 mM L-glutamine (unless otherwise stated). The cell lines were cultured in the indicated media and had the following growing additives where specified; MCF7, MDA-MB-231, B16-F10, PD-MBM1, PD-MBM2 and PD-MBM3 cells were cultured in Eagle's Medium (DMEM). 4T1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 mM Hepes buffer, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 2.5 g/L D-glucose. 131/4-5B1, WM239A and RMS cells were cultured in RPMI 1640. A375 cells were cultured in RPMI as described above with addition of 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10 mM HEPES buffer. WM115 cells were cultured in MEM supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA). D4M.3A cells were cultured in DMEM advanced medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% L-GluMAX. Phenol red-free media were used for the fluorescence sensitive assays. Cells were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Labeling OCT tissue sections with NIRF-ABP

Normal mammary fat pad tissues, normal human skin, 4T1 mammary tumors and 131/4-5B1 melanoma tumors were embedded in optical cutting temperature (OCT) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to cryosectioning. Normal human skin was collected after obtaining written informed consent from research subjects at Hadassah Medical Center, Jerusalem, under an approved institutional review board (IRB) (HMO-14-0367). Normal mammary sections of 15 µm and 10 µm sections for the rest of the tissues were mounted on histology glass slides and fixed with paraformaldehyde 4% in PBS for 30 min at 4 °C, then washed 3 times with PBS for 5 min. For cathepsins staining, slides were incubated for 1 h with 0.25 μΜ GB123 at 37 °C in a reaction buffer (50 mM acetate, 4 mM DTT and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 5.5) with or without pre-incubation with 2.5 μM GB111-NH2, a cathepsin inhibitor 49. Slides were then washed overnight in phosphate-buffered saline at 4 °C. Slides that were previously treated with GB111-NH2 were treated with additional 1 µM GB111-NH2 and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Finally, all slides with labeled tissues were mounted with ProLong® Gold antifade reagent with 4′ 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The stained sections were visualized using confocal microscopy with DAPI and Cy5 lasers and filters as described below.

Labeling of lysed tissues with NIRF-ABP

Normal mammary fat pad and normal human skin tissues, MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 mammary tumors, 131/4-5B1, D4M.3A, A375 and RMS mCherry-labeled melanoma tumors were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and lysed on ice with RIPA buffer by means of gentleMAX dissociator. The obtained lysates were centrifuged for 10 min (18500 rcf, 4 °C), supernatant was collected and protein amount was quantified by Bradford assay. An equal amount of 30 µg protein was pretreated with 5 µM GB111-NH2, or DMSO (indicated samples) for 45 min in reaction buffer as described in the supplementary information, at 37°C. GB123 (2 µM) was added to all samples for 90 min at 37 °C. The reaction was terminated by addition of 5X sample buffer (10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 6.8, 3% SDS and 5% β-mercaptoethanol) and boiling. Finally, proteins were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and scanned for fluorescently labeled proteases by a Typhoon scanner FLA 9500 at excitation/emission wavelengths 635/670 nm.

Confocal microscopy

Intact cells and explants of normal or tumor tissue sections labeled with GB123 as well as fluorescent explant tumor tissues following i.v. injection of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ were monitored utilizing Zeiss Meta LSM 510 and Leica TCS SP8 confocal imaging systems with 60× oil objectives (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar Germany). All images were taken using a multi-track channel acquisition to prevent emission crosstalk between fluorescent dyes.

In vitro co-localization with lysosomes and cellular uptake of Turn-ON probes

For the in vitro co-localization of Turn-ON probes with lysosomes, 131/4-5B1 and 4T1 cells (2,000,000 cells/well or 1,000,000 cell/well respectively) were seeded in 10 cm petri dishes one or two days before treatment, respectively. For co-localization with lysosomes, cells were treated with 500 nM Cy5-eq. concentration P-GFLG-Cy5 and PC for 2 h. In the last 0.5 h, 100 nM LysoTracker™ Green DND-26 (Life technologies) was added to the 10 cm petri dishes. For cellular uptake evaluation, cells were treated with 500 nM Cy5-eq. concentration of PCQ or P-GFLG-Cy5 conjugates and with free Cy5 in the same concentration for 30 and 60 min, respectively. Growth medium was replaced with the treatment solutions. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with phenol red-free RPMI medium for 1 h. For the Turn-ON evaluation in living cells, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with phenol red-free RPMI medium for 0, 0.5, 1 and 16 h post treatment removal. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and detached from the petri dish by incubation with phenol red-free trypsin for 5 min. Then, 6 mL of 2% FBS/PBS was added and the cells were centrifuged for 7 min at 200 rcf (4 °C). The cells were resuspended in 50 µL of 2% FBS/PBS and analyzed using an ImageStream®X Mark II Imaging Flow Cytometer for co-localization or cellular uptake by fluorescence signal evaluation. Similarity (co-localization) threshold was set as above 1.5 (AU) fluorescence signal intensity of red and green overlapping pixels.

Animals and tumor cell inoculation

BALB/c mice (aged 6-8 weeks) were inoculated with 1×106 4T1 cells into the mammary fat pad using a 27-gauge needle, and SCID mice were inoculated intra-dermally with 5×105 131/4-5B1 or A375 mCherry-labeled cells. Nu/nu mice were inoculated intra-mammary with 1×106 MDA-MB-231 cells. C57BL/6J mice were inoculated intra-dermally with 5×105 D4M.3A and RMS cells. Intra-dermal and intra-mammary injection volumes were 50 and 100 µL, respectively. Mice were monitored every other day for body weight changes and tumor growth was measured using a caliper. Tumor volume was calculated using the standard formula: length × width2 × 0.52. Mice bearing 4T1 tumors that did not undergo surgery were euthanized 22 days post inoculation according to IACUC regulations (tumor sizes were above 1000 mm3).

Fluorescence imaging

BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 tumors (~100 mm3) were injected intravenously (i.v.) with P-GFLG-Cy5 (10 μM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL saline; 4-9 mice per group). SCID mice bearing 131/4-5B1 melanoma tumors (~100-150 mm3) were injected i.v. (10 μM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL) with PCQ. Fluorescence signal within tumor was assessed using the non-invasive imaging system CRI MaestroTM at different time points, starting at 1 min, up to 24 h following injection into BALB/c mice or into SCID mice. Multispectral image cubes were acquired through the 650-800 nm spectral range in 10 nm steps using excitation (635 nm longpass) and emission (675 nm longpass) filter sets. Mouse auto-fluorescence and undesired background signals were eliminated by spectral analysis using the linear unmixing algorithm.

Survival surgery

Survival surgeries with P-GFLG-Cy5 fluorescence guidance (IGS group) or under white light (control group) were performed on xenografts of 4T1 or 131/4-5B1 cells. Both groups had similarly sized 4T1 or 131/4-5B1 tumors (~100-150 mm3). Animals were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylasin and hair was removed with a depilatory cream. All surgical procedures were performed in sterile conditions. The IGS group was injected i.v. with P-GFLG-Cy5 or PCQ probes (10 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL saline). Four hours following i.v. injection, intravital imaging by CRI MaestroTM was performed, as described above, before surgery and during all steps of surgery (intact animal, following skin incision over the tumor and during tumor excision). The control groups underwent surgery under white light illumination, or under 5-ALA or ProSense® 680 guidance. 5-ALA (0.1 mg/g) was administered per os 4 h prior to surgery. Prosense® 680 (2 nmol in 150 µL PBS pH 7.4) was administered i.v. into the tail vein 4 or 24 h prior to surgery. Hemostasis was measured with a handheld hemostat. Images of the fluorescence signal were displayed on an adjacent monitor and all Cy5-positive tissue foci (suspected as tumor tissues) were excised. Following completion of tumor excision, both with or without fluorescence guidance, skin incisions were sewn and animals were returned to their cages to recover from the anesthesia. Complete tumor excision was assessed by fluorescence signal (background level, n=4) or white light (control group, n=4).

Post-surgery tumor recurrence follow-up

Both IGS and control groups (no guidance, 5-ALA and ProSense® 680) were monitored for tumor recurrence. All mice were weighed twice a week. Tumor follow-up was monitored both by palpitation of the surgical area and by fluorescence imaging 4 h following i.v. injection of P-GFLG-Cy5 (10 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL saline). Recurrence was observed by optical (fluorescence) imaging and by histology with H&E staining. Three exclusion criteria were determined in advance: above 10% weight-loss, tumor recurrence size was above 400 mm3 and/or neurological disorders. Mice with one of the above criteria were assessed by CRI MaestroTM imaging and by white light for metastasis spread and then euthanized.

Tissue histology

As described above, during post-surgery tumor recurrence follow-up, mice were imaged by CRI MaestroTM (filter set: λEx: 635 nm, λEm: 650-800 nm, filter: 675 nm) 4 h post i.v. injection of P-GFLG-Cy5 (10 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL). Tissues that showed an increased Cy5 signal were suspected as recurrent or metastatic cancerous tissues, and were then excised and stained for H&E for further histo-pathological analysis. The suspected cancerous tissues were embedded in paraffin or OCT. Prior to OCT embedding, excised tissues were incubated with 4% PFA in PBS for 4 h followed by incubation in PBS for 12 h and 1 M sucrose (BioLab) overnight. For paraffin-embedded fixation, tissues were kept for 48 h in 4% PFA in PBS, then processed using a Tissue Processor (Leica) for 10 h and then embedded in paraffin using a Leica Tissue Embedder. 5 µm sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Excised sternum tissues were fixed in 4% PFA and decalcified for 14 days in 14% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), embedded in OCT and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to cryosectioning. 10 μm sections were obtained and stained by H&E. Sequential sections obtained from IGS were mounted with ProLong® Gold antifade reagent with DAPI and examined by confocal microscopy to evaluate Cy5 internalization into cells.

Statistical methods

Data is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for in vitro assays or ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for in vivo results. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

Ethics statement

All animal procedures were approved and performed in compliance with the standards of Tel Aviv University, Sackler School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Results

Design of self-quenched/FRET-based Turn-ON probes activated by cathepsins

Cysteine cathepsins are lysosomal cysteine proteases overexpressed in several tumor types 50. The high levels of cathepsins can be harnessed for specific activation at the tumor site. We exploited this property in order to design several Turn-ON probes, which can be activated to generate a fluorescence signal upon reaction with tumor cathepsins. The Turn-ON probes are otherwise optically silent due to Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between dye-dye (Cy5-Cy5) or dye-dark quencher (Cy5- quencher) molecules. We designed three cathepsins-activatable polymeric Turn-ON probes composed of two different polymeric backbones as the macromolecular carrier. The first, system 1, was recently reported by our group 31, and is composed of HPMA copolymer bearing covalently bonded Cy5 molecules via a tetra peptide spacer, Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly (GFLG), which is a known cathepsins substrate. The activation to its Turn-ON state at the tumor site occurs by cathepsin cleavage of the tetra peptide. Upon cleavage of the GFLG linker, Cy5 molecules that are covalently bound to it are detached and move apart, resulting in elevation of the fluorescence signal (Figure 1A). The second polymeric backbone, utilized in systems 2 and 3, is poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA), which is biodegradable by cathepsins. PGA was designed to be covalently linked to multiple Cy5 molecules to generate the PC conjugate, which possess self-quenching interactions between the fluorophores (system 2). PCQ was designed to be generated from the former PC by the addition of quencher molecules, thus introducing FRET quenching interactions into this system (system 3). The three polymeric systems are designed to be activated to their Turn-ON state by two different mechanisms. The first activation is by the GFLG linker cleavage and the second is by backbone degradation (Figure 1A). We sought to compare the two systems' fluorescence signal recovery upon challenging with CTSB in vitro and cathepsins in vivo to determine their potential application as guiding agents for real-time image-guided surgery. Our Turn-ON probes' characterizations were compared to those of “Always ON”, non-cleavable and “Never ON” probes and are described in Scheme S1.

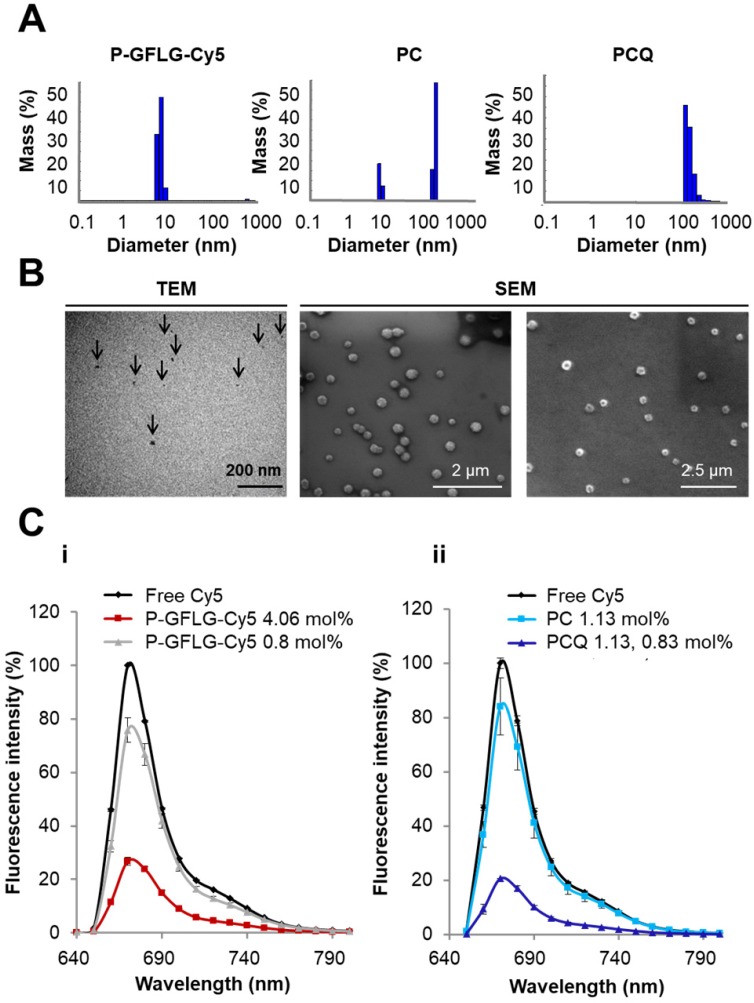

Synthesis and characterization of HPMA copolymer-GFLG-Cy5 (P-GFLG-Cy5) Turn-ON probe

P-GFLG-Cy5 conjugate was synthesized bearing 4.06 mol% loading of Cy5 (6.3 dyes per polymer chain). Its fluorescence spectrum was characterized in order to evaluate both the self-quenching of the conjugated fluorophore and its biodegradability by cathepsins. The synthesis scheme of the P-GFLG-Cy5 conjugate is represented in Figure 1B. The hydrodynamic diameter size distribution of P-GFLG-Cy5 conjugate was determined using a Möbius dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyzer. The mean hydrodynamic diameter was ~7 nm (Figure 2A, Table 1), which correlates well with imaging results obtained from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, showing an average particle size of 8.5 ± 3.5 nm (Figure 2B, Table 1). This particle size is ideal for in vivo imaging as recent clinical trials were conducted using ~7 nm particles 51. In addition, this size is below 10 nm, which is reported to be optimal for imaging and diagnostics for surgical procedures, due to their better escape ability from the mononuclear phagocyte system, compared to particles with bigger hydrodynamic diameter 52. Furthermore, this particle is small enough to quickly travel with the lymphatic flow to the tumor, but large enough to retain there via the EPR effect, in order to be detected and optically guide surgical procedures. Table 1 summarizes the properties determined for each conjugate.

Figure 2.

Physicochemical characterization of the Turn-ON probes. (A) DLS measurements of the hydrodynamic diameter of P-GFLG-Cy5 (0.5 mg/mL, saline), PC (1 mg/mL, DDW) and PCQ (1 mg/mL, DDW) conjugates. (B) Electron microscopy of (from left to right) a representative TEM image of P-GFLG-Cy5 (1 mg/mL, saline), and representative SEM images of PC (0.01 mg/mL, DDW) and PCQ (0.1 mg/mL, DDW) conjugates. TEM and SEM images are representative of 3 fields of view, with 10 or 20 particles per field, respectively. (C) i. Effect of Cy5 loading on the quenching efficiency of P-GFLG-Cy5 conjugates with different payloads of Cy5. ii. Effect of the addition of quencher molecules to generate FRET PCQ system on the quenching efficacy vs. a self-quenching PC system. All conjugates were measured at the same Cy5-eq. concentration (5 μM). Fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing payload of Cy5 on HPMA copolymer conjugates and when introducing quencher molecules to generate PCQ conjugate. Filter set: λEx: 630 nm, filter: 665 nm, λEm: 670 nm. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Table 1.

Physicochemical characterization summary:

| Conjugate | Mw (kDa)a | Hydrodynamic diameter size DLS (nm)b | Diameter size electron microscopy(nm)b | Total Cy5 loading (%mol)c |

Total quencher loading (%mol)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-GFLG-Cy5 | 36.41 | 7.17±1.17 | 8.5±3.5 | 4.06 | N/A |

| PC | 10.56 | 7.9±0.45 247.5±11.2 |

220±45 | 1.13 | N/A |

| PCQ | 11.04 | 152±41 | 115±25 | 1.13 | 0.83 |

atheoretical value, bdetermined by DLS instrument cdetermined by spectroscopic measurement by SpectraMax M5e multi-detection reader at λ=630 nm.

Synthesis and characterization of PC and PCQ Turn-ON probes

Two PGA-based conjugates were synthesized, PC (1.13 mol% loading of Cy5) and PCQ (1.13 mol% of Cy5 and 0.83 mol% loading of quencher). The synthesis scheme is depicted in Figure 1B. Their hydrodynamic size distributions were analyzed by DLS. The PC conjugate size distribution was found to have two main populations of 7.9 ± 0.45 and 247 ± 11.2 nm (Figure 2A, Table 1). The smaller population was measured to be 25% of the mass population according to DLS measurement. The larger population displaying a size of around 247 nm is probably due to supramolecular assemblies of the conjugate at the measured concentration. The PCQ conjugate size was determined by DLS to be 152 ± 41 nm (Figure 2A, Table 1). These results were in good correlation with the imaging results obtained from the SEM analysis (Figure 2B, Table 1). The particle measurements for PC and PCQ conjugates were 220 ± 45 nm and 115 ± 25 nm, respectively. SEM measurement of PC conjugate showed the larger population due to the limit of detection sensitivity of this method. The slightly larger size measured by DLS relative to that by SEM may be attributed to the larger hydrodynamic size of particles in solution, which includes the attached water molecules solvating the polymer 53.

Turn-ON probes quenching capacity increased with higher dye or quencher payloads

As previously reported, we postulated that the loading of the fluorophore is critical for optimal performance 54. At low fluorophore loading, only limited quenching may be observed; these probes may also be referred to as Always ON probes. However, at high fluorophore loading, Turn-ON may not occur due to steric hindrance between the enzyme and its target site 54. These probes may also be referred to as Never ON probes. To define the optimal loading of Cy5 dyes on HPMA copolymer for efficient quenching, two P-GFLG-Cy5 conjugates bearing different Cy5 loadings were synthesized and their fluorescence spectra were characterized (Figure 2Ci). As expected, higher loading of Cy5 molecules on the probe led to increased quenching efficiency, as reflected by a lower fluorescence signal, resulting from the close proximity of one dye to another. In contrast, at low fluorophore loading, only limited quenching was observed (Figure 2C). Figure 2Ci demonstrates that for 0.81% Cy5 loading (1.4 dyes per polymer chain) and 4.06% (6.3 dyes per polymer chain), the signal intensity was reduced to 75% and 27%, respectively, relative to free Cy5. Furthermore, we compared the addition of dark quencher molecules generating FRET, to self-quenched (homo-FRET) Cy5 molecules on the PGA polymeric backbone. Indeed, for PCQ, the FRET-based conjugate, there was a higher quenching efficiency in comparison with the PC, a self-quenched Cy5-bearing PGA polymer. The fluorescence signal was decreased from 84% to 20% of an equi-molar free Cy5 concentration (Figure 2Cii). The fluorescence signal of free Cy5 was set as 100%. As control, Always ON and Never ON probes were synthesized at low (Always ON) and high (Never ON) loading of PGA bearing Cy5 probes (0.56 mol% and 12.5 mol%, respectively). A middle payload of 3.3 mol% Cy5 was compared as well, as an additional self-quenched Turn-ON probe. As expected, the lowest Cy5 loading (0.56 mol%) was not quenched at all, and was referred as our Always ON probe, while the medium Cy5 loading (3.3 mol%) resulted in decreased quenching compared to the highest quenching of the conjugate bearing the highest Cy5 loading (12.5 mol%), and was referred as our Never ON probe (Figure S4A, C).

In vitro and in vivo cathepsin enzymes activity

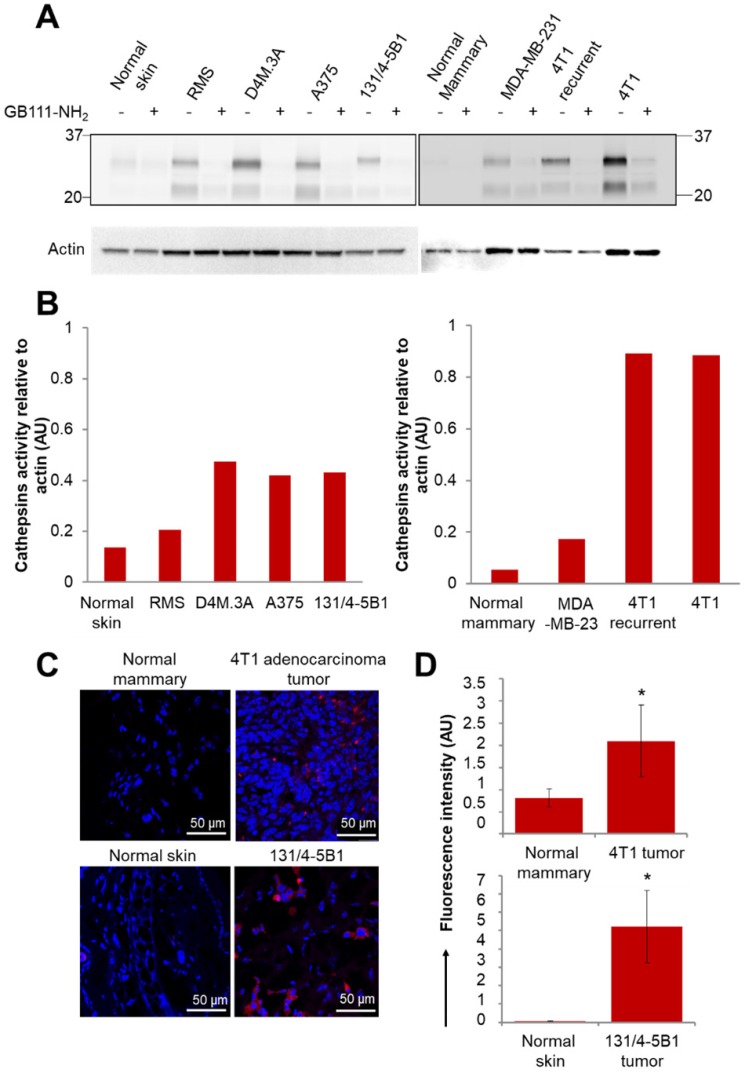

We first validated the activity of cathepsins in multiple cancer cell lines. The activity was evaluated by a fluorescently labeled cathepsins activity-based probe (ABP), GB123, and validated by a cathepsins inhibitor, GB111-NH2 48, 49. We isolated the proteins from mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines (murine 4T1 and DA3, human MDA-MB-231 and MCF7) and from melanoma cell lines (murine B16-F10 and RMS, human A375, WM115 and patient-derived PD-MBM1, PD-MBM2, PD-MBM3). Cathepsins were found to be highly active in most of the tested melanoma cell lines (Figure S5A). MDA-MB-231 cell line did not show high cathepsin activity in vitro; however, it is established that cathepsins are overexpressed in those tumors in vivo as a result of immune cell recruitment to the tumor microenvironment 55. In order to demonstrate a Turn-ON activation in vivo, we further evaluated the activity of cathepsins in tumor tissues lysates of melanoma and mammary adenocarcinoma tumors. Orthotopic tumor tissues of melanoma RMS, D4M.3A, A375 and 131/4-5B1 and mammary adenocarcinomas 4T1, 4T1 tumor recurrence and MDA-MB-231 were lysed and proteins were extracted. We found high cathepsins activity in the tumors in comparison with normal tissues (skin or mammary fat pad), both by evaluation of mammary and melanoma cancer cell lines (Figure S5A), tumor tissue, skin and mammary fat pad lysates (Figure 3A-B) and by scanning tumor and healthy sections using confocal microscopy (Figure 3C-D). The tissue lysate of the recurring 4T1 tumor showed a similar activity of cathepsins in comparison with the original 4T1 tumor. Treatment with GB111-NH2, a cathepsins inhibitor served as control, marked as (+), and was added to the samples before and during treatment with the labeled ABP, GB123. As expected, the tumor lysates pretreated with the inhibitor as control (+), did not exhibit the active cathepsins band, since it inhibits the enzyme activity without labeling it.

Figure 3.

Active cathepsins labeling of tumor lysates and normal tissues with activity based probe (ABP), GB123. (A) Labeling of active cathepsins in melanoma and breast cancer tumor tissues, in comparison with normal tissues (normal skin and normal mammary). Equal amounts of protein were pretreated with 5 µM cathepsins inhibitor, GB111-NH2 (+), or DMSO (-) for 45 min in reaction buffer at 37 °C. GB123 (-), 2 µM, was added to all samples for 90 min at 37 °C. Finally, an amount equivalent to 30 µg of protein was separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE. GB111-NH2 (+) served as control. Labeled proteases from lysed cells and tissues were visualized by scanning the gel with a Typhoon scanner at excitation/emission of 635/670 nm. The fluorescent bands between 20-37 kDa are characteristic of cathepsin enzymes, as was previously demonstrated 49, 77. Loading control for western blot was actin. (B) Graphs show the quantification of cathepsins' activity relative to actin in normal and tumor tissue lysates. (C) In vivo cathepsins expression (red) in breast (4T1) and melanoma (131/4-5B1) tumor sections in comparison with normal tissues, mammary fat pad and skin, respectively. Red indicates Cy5 fluorescence of GB123; blue indicates DAPI. (D) Quantification of the signal obtained from tumor tissue slides in comparison with normal tissue slides using ImageJ software. Data represent mean ± SD.

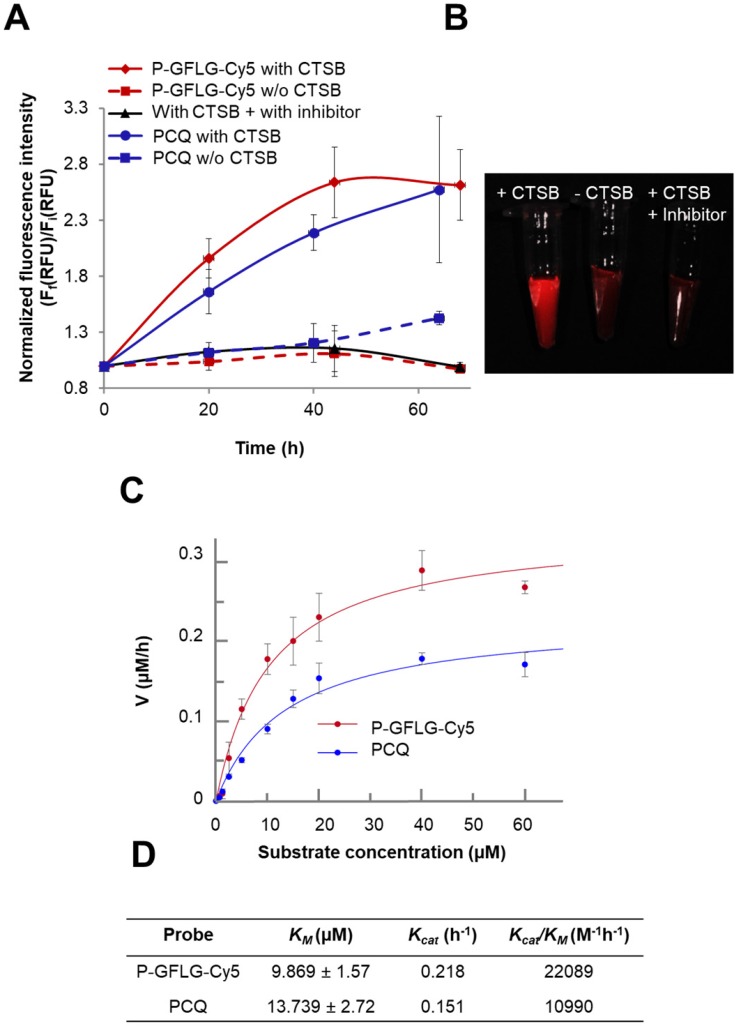

In vitro Turn-ON capacity and enzymatic degradation kinetics of the activatable probes

CTSB is one of the members of the cysteine cathepsins family. CTSB-mediated degradation and release of Cy5 from P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ over time is described in Figure 4A-B. In order to evaluate the increase in fluorescence intensity due to CTSB enzymatic cleavage, the Turn-ON probes were incubated in the presence of CTSB (37 °C, pH 5.5) and the release of Cy5 was assessed by fluorescence signal measurements (Figure 4A). Samples (100 µL) were collected at different time points and measured by a spectrophotometer. As expected, measured fluorescence intensity dramatically increased over time and plateaued after 44 h for P-GFLG-Cy5. In the absence of the enzyme or upon incubation of the enzyme with CTSB inhibitor (CA-074 Me), the increase in fluorescence signal was negligible. Monitoring the release of Cy5 by HPLC is presented in Figure S6. The Cy5 release kinetics of the two different Turn-ON probes were quite similar despite the different sites of degradation, i.e., GFLG linker vs. PGA polymeric backbone of the P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ, respectively. Next, we evaluated CTSB activity on our control probes. These probes included Always ON (PC 0.56 mol%), Never ON (PC 12.5%) and non-cleavable probe composed of HPMA copolymer-Gly-Gly-Cy5 (P-GG-Cy5) 1.14 mol% (Figure S4B, D). The results indicate that our control probes' increase in fluorescence signal was negligible in the presence nor in the absence of CTSB.

Figure 4.

Turn-ON properties and kinetics of degradation by CTSB of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ conjugates. (A) Cy5 fluorescence is turned-ON upon incubation with CTSB (0.56 U/mL), while in the addition of an inhibitor (CA-074 Me) and in the absence of CTSB, a negligible increase in fluorescence signal was observed. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) Representative CRI MaestroTM image of P-GFLG-Cy5 probe incubated with CTSB, and controls (no enzyme, and an addition of CTSB inhibitor, CA-074 Me). (C) Kinetics of the degradation of Turn-ON probes by CTSB. Various concentrations of P-GFLG-Cy5 (red) and PCQ (blue), from 0-60 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, were incubated with CTSB 0.2 U/mL at 37 °C for 24 h, and the initial velocity values (v) were analyzed by GraFit 7.0 software. (D) Table of kinetic parameters of the Turn-ON probes for CTSB (0.2 U/mL). Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

Therefore, we concluded that our Turn-ON probes, P-GFLG-Cy5 with 4.06 mol% Cy5 loading, and PCQ bearing 1.13 mol% Cy5 and 0.83 mol% quencher, exhibited satisfactory quenching properties and activation by CTSB. In addition, under lysosome-mimicking conditions, pH ~5, the conjugates were relatively optically silent in their quenched state (i.e., Turn-OFF), and become highly fluorescent after enzymatic cleavage of the GFLG linker or PGA backbone by CTSB. Other enzymes may degrade these polymeric Turn-ON probes. In addition to CTSB enzyme, the GFLG linker may also be degraded by papain 56, chymotrypsin, which can cleave peptide bonds followed by phenylalanine (Phe) 57, dipeptidyl aminopeptidase BII (DAP BII), which may hydrolyze Gly-Phe substrate 58, and orphyromonas gingivalis DPP-7 (PgDPP7), which may hydrolyze Leu-Gly substrate 59, 60. The overexpression of cathepsins, such as B, S and L, is known to vary between tumor types. Thus, cysteine cathepsin-activated probes might be applied in any tumor type in which one or more of those proteases are overexpressed. In order to compare the different activation by different cathepsins that are overexpressed and active at the tumor site, we incubated our Turn-ON probes with different human recombinant (hr) cathepsins—B, L and S. P-GFLG-Cy5 showed different degrees of degradation by each of them (highest degree for CTSL and lowest degree for CTSS). The PCQ Turn-ON probe was also degraded by all of the hr cathepsins to a different extent, with highest degradation by CTSB and lowest by CTSL (Figure S5B). In the absence of the enzymes, the elevation in the fluorescence intensity was negligible. This indicates the stability towards hydrolysis at different pH (4.5, 5.5 and 6), which might characterize the tumor microenvironment local pH (5.5-7.0) 61-63, or the pH in the lysosome (pH 5-5.5) where cathepsins are highly active. Nevertheless, the microenvironment of many solid tumors is weakly acidic (pH 6.5) 64. To further study the difference in site of degradation between the two probes, their enzymatic efficiency was evaluated according to kinetics constants calculated from the Michaelis-Menten equation. The KM of PCQ was slightly higher than that of P-GFLG-Cy5 (13.739 vs. 9.869 µM, respectively) (Figure 4C), indicating formation of a more loosely-bound complex with CTSB than that of P-GFLG-Cy5 with the enzyme. Similarly, the turnover number of the enzyme, Kcat, was higher for P-GFLG-Cy5 than for PCQ (0.218 vs. 0.151 h-1, respectively), indicating a more rapid degradation of the GFLG linker to release free Cy5 per hour, than the degradation of PGA polymeric backbone. Overall, the enzymatic efficiency (Kcat/KM) of P-GFLG-Cy5 was higher than that of PCQ (22089 vs. 10990 M-1h-1, respectively) (Figure 4C-D).

Inhibition of CTSB activity increases as inhibitor concentration rises

The degradation of GFLG spacer on P-GFLG-Cy5 by CTSB was inhibited by the selective CTSB inhibitor, CA-074 Me, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S4E-F). As inhibitor concentrations increased from 0 to 250 µM, the fluorescence signal was decreased to about half of the original signal of non-inhibited probe (Figure S4E-F). This indicates a selective inhibition of the probe activation that possesses a concentration dependence.

Enhanced in vitro cellular retention and Turn-ON properties of the activatable conjugates

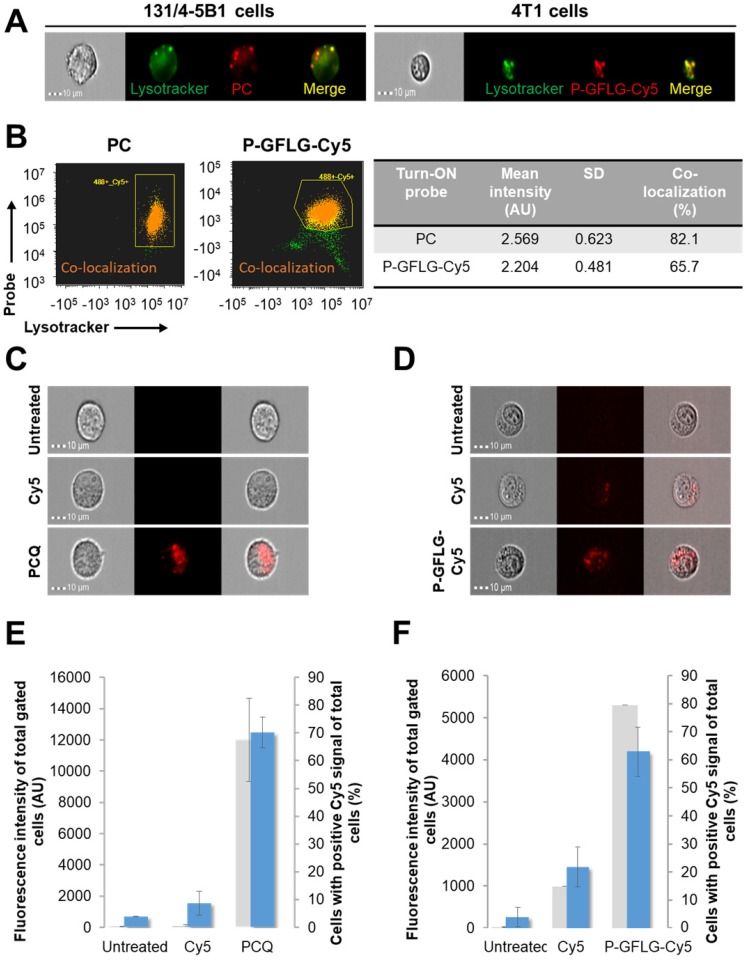

Macromolecular carriers can internalize into cells through endocytosis. Our probes are designed to be degraded by cysteine cathepsins, which cleave the linker GFLG in the HPMA copolymer-based probe, to release the free fluorophore with its terminal amine. The slightly acidic pH ~5 in lysosomes and the slightly less acidic endosomes, the main sites of enzymatic degradation, may lead to protonation of this amine functional group 65. The fluorophore that is positively charged after enzymatic cleavage may diffuse in a slower rate through the lysosome membrane, leading to its higher retention there 66. This phenomenon is termed the lysosomotropic effect, and was recently reported for a low MW enzyme-activatable Turn-ON probe 67. As our Turn-ON probes bear densely packed fluorophore molecules that generate positively charged fluorophores upon degradation by cathepsins (Figure S6A), we postulated that in the pH range of lysosomes (~5) 68 the Cy5 signal detected in vitro in the cells might be higher for our Turn-ON probes, in comparison with free Cy5 molecules, at equivalent dye concentrations. For the PGA-based probe, we postulated that the signal might be higher as it may be recognized by γ-glutamyl transpeptidase in the cell membrane, resulting in a significant increase in its cellular uptake 69. The fluorescence signal of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ probes in live murine mammary adenocarcinoma 4T1 and human melanoma 131/4-5B1 cells was measured using an ImageStream®X Mark II Imaging Flow Cytometer. First, we wanted to evaluate whether our Turn-ON probes are co-localized with the lysosomes. 4T1 and 131/4-5B1 cells were stained with a lysosome marker, LysoTracker green, and incubated with P-GFLG-Cy5 and PC Turn-ON probes (respectively) at 37 °C for 2 h. The live cell imaging results are presented in Figure 5A. Co-localization analysis of red (Turn-ON probes) and green (lysosomes stained by LysoTracker green) pixels showed 65.7% and 82.1% co-localization, respectively (Figure 5B). Further, after validating that our probes went through the lysosome compartment, we sought to examine whether the retention time was longer in comparison with free Cy5. The cells were incubated at 37 °C with P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ for 1 h and 0.5 h, respectively. For both conjugates, cellular uptake and retention were compared with free Cy5 and untreated cells.

Figure 5.

In vitro co-localization with lysosomes and enhanced retention of PC (left) and P-GFLG-Cy5 (right) Turn-ON probes. (A) Representative fluorescence imaging of living 131/4-5B1 melanoma and 4T1 cells treated by LysoTracker® Green (green), a lysosome marker, and Turn-ON probes (red), PC (left) and P-GFLG-Cy5 (right), 2 h post incubation. (B) Analysis of imaged living cells showed 82.1% and 65.7% co-localization (dot plot - orange) of the lysosome marker, LysoTracker® Green, with PC (left) and P-GFLG-Cy5 (right), respectively. Yellow indicates cells with green (Lysotracker) and red (suitable Turn-ON probe) staining (without co-localization), orange indicates co-localization and green indicates non-gated cells. Similarity signal intensity that represents the co-localization of cells with co-localization is presented in the table. (C-D) The cellular uptake of Turn-On probes is higher than that of free Cy5: Internalization of (C) PCQ and (D) P-GFLG-Cy5 probes into live 131/4-5B1 melanoma and 4T1 murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells. Live cells were monitored 1 h following treatment with free Cy5 and the probes. Untreated cells served as control. Brightfield and fluorescence images of (C) PCQ uptake by 131/4-5B1 cells and (D) P-GFLG-Cy5 uptake by 4T1 cells. (E-F) Mean cell fluorescence intensity (blue columns) and percentage of positive cells with Cy5 signal (gray columns) upon (E) PCQ uptake and upon (F) P-GFLG-Cy5 uptake. Free Cy5 uptake and untreated cells served as control in both cell lines. All fluorescence images were obtained using an ImageStream®X Mark II Imaging Flow Cytometer and analyzed by the supplier software. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Then, in order to follow the cellular uptake and retention of our probes, the treatments were replaced with cell growth medium for 1 h and the live cells were monitored. Figure 5C-D shows brightfield and fluorescence images of the cells with the probes, Cy5 or without treatment. The fluorescence intensity from the cells treated with our Turn-ON probes was higher than that of free Cy5-treated cells (untreated cells served as control and the threshold for positive Cy5 signal was determined according to them). Treatments with our polymeric Turn-ON probes resulted in a high fluorescence signal of ~4190 AU and ~12474 AU for P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ, respectively. Free Cy5 fluorescence signal was significantly lower, about ~1450 AU and ~1541 AU, respectively. Untreated 4T1 and 131/4-5B1 cells displayed a fluorescence signal of about ~260 AU and ~690 AU, respectively (Figure 5E-F). In addition, the percentage of cells bearing positive Cy5 signal was evaluated. A similar trend was observed for P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ polymeric probes. For the higher fluorescence intensity, there was larger number of cells with positive Cy5 signal (~80% and ~67% of total cells, respectively). For the free Cy5-treated 4T1 and 131/4-5B1 cells, the percentage of cells with positive Cy5 signal out of the total number of cells was lower, with ~15% and none, respectively (Figure 5E-F). When incubation was prolonged (up to 16 h), there was an increase in fluorescence intensity, indicating activation of the PCQ system to its Turn-ON state (Figure S5C, upper and middle panels, and Figure S5D), probably by cathepsins that are highly activated in 131/4-5B1 melanoma cells (Figure S5A). In addition, we showed the specific inhibition of our Turn-ON probe's activation by cathepsins via pre-incubation of 131/4-5B1 living cells with cathepsin inhibitor GB111-NH2 prior to treatment with PCQ. The fluorescence signal of the cells 1 h following treatment removal was almost abolished for PCQ + GB111-NH2 in comparison with 131/4-5B1 cells that were incubated only with PCQ (Figure S5C, lower panel). These findings indicate that our probes are superior over small molecules as imaging agents. They resulted in a higher fluorescence signal upon in vitro incubation with different cancer cell lines, and presented Turn-ON ability upon cellular incubation.

In vivo characterization and pharmacokinetics (PK) of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PGA-based Turn-ON probes

For further in vivo evaluation of our Turn-ON probes, we rationally chose to focus on the P-GFLG-Cy5 system 1 and PCQ system 3, which had superior characteristics in terms of size and quenching capabilities. HPMA copolymer and PCQ sizes measured by DLS were ~7.17±1.17 nm and ~152±41 nm, respectively (Table 1). The P-GFLG-Cy5 size was within the suitable size range of imaging agents for IGS, i.e., below 10 nm 52. The PCQ polymeric Turn-ON probe with a size within 50-200 nm could show better accumulation at the tumor site 29. In order to study our Turn-ON probes' properties in vivo, and to choose the ideal time for image-guided surgery, we followed the kinetics and tumor-to-background elevation of the Turn-ON probes by non-invasive imaging of BALB/c or SCID mice inoculated orthotopically with 4T1 mammary adenocarcinoma or 131/4-5B1 melanoma cells, respectively. In the breast cancer model, 4T1 cells were inoculated into the 1st mammary gland of mice to generate tumors, while melanoma cells were injected intra-dermally to the flank. In order to emphasize the importance of Turn-ON probes for in vivo imaging, in terms of providing an improved tumor-to-background signal, our control probes, non-cleavable P-GG-Cy5 and the Always ON PC 0.56 mol% probes were injected i.v. to BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 tumors. Mice were imaged non-invasively using a CRI MaestroTM imaging system at 15 min to 4 h post i.v. administration (Figure S7A-B). No elevation in the tumor-to-background signal of the non-cleavable and Always ON probes was observed over time, and the tumor could not be easily distinguished (Figure S7A-C). However, for the Turn-ON probe, we found that the tumor-to-background ratio was elevated over time, reaching the highest signal 4 h post i.v. administration, thus the location of tumors could be detected non-invasively (Figure S7A-B, lower panel). Macromolecules such as polymeric probes may accumulate in the tumor site via the EPR effect. In order to exclude that the elevation in fluorescence signal occurred only due to accumulation of the probe at the tumor site via the EPR effect, we injected the probe intratumorally (100 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, 30 µL) and the fluorescence signal from the tumor was measured over 60 min. An elevation in the fluorescence signal during that time showed that our probe possesses Turn-ON properties in vivo, in addition to the accumulation that occurs via the EPR effect (Figure S7D). Indeed, the Always ON control probe showed that during 4 h post i.v. injection, the EPR effect alone does not provide a clear detection of the tumor boundaries vs. the healthy tissue. Finally, evaluation of the pharmacokinetics (PK) of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PC Turn-ON probes in 4T1 and Ret melanoma tumor-bearing BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice resulted in t1/2 of 19 and 22 min, respectively. Most of the detectable conjugates were excreted from the plasma 3 h post i.v. injection (Figure S8B). These results were in good correlation with the highest accumulation in the tumor 4 h post i.v. administration for P-GFLG-Cy5 Turn-ON probe. In addition, the probes were stable in different media mimicking physiologic conditions up to 100 h (Figure S8A).

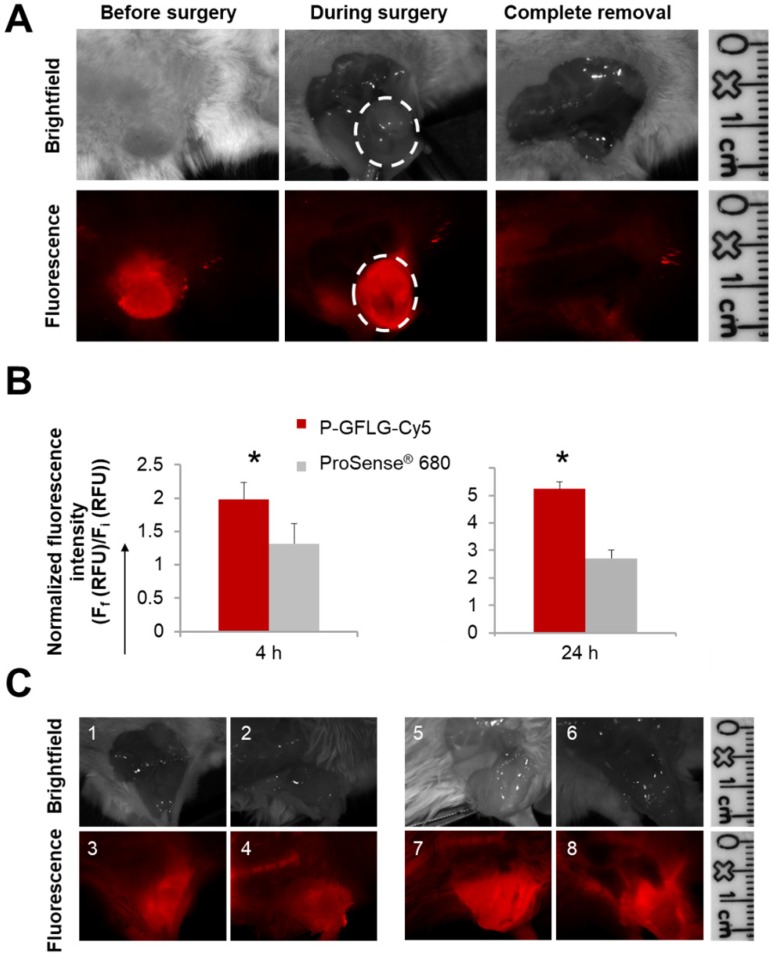

Surgery under P-GFLG-Cy5 guidance

To test the ability of our Turn-ON probes to delineate the tumor boundaries and differentiate healthy and cancerous tissue, P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ were injected i.v. into the tail vein of BALB/c or SCID mice inoculated orthotopically with 4T1 mammary adenocarcinoma or 131/4-5B1 melanoma cells, respectively, as described in the PK studies. Based on our PK and tumor-to-background studies (Figure S7 and Figure S8), we determined the IGS time point to be 4 h post i.v. injection of P-GFLG-Cy5 (10 µM, 200 µL). At this time point, the location of the tumor could also be detected non-invasively (Figure 6A). Surgical resection of the mammary adenocarcinoma and melanoma tumors was performed using the CRI MaestroTM imaging system under P-GFLG-Cy5 fluorescence signal guidance for the breast cancer model (Figure 6A), and under PCQ guidance for the melanoma model.

Figure 6.

Surgeries performed under the guidance of P-GFLG-Cy5 (10 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL saline) and ProSense® 680 (2 nmol, 150 µL PBS). (A) Surgical field representative images of the surgery performed under P-GFLG-Cy5 guidance. IGS was performed 410 min post i.v. injection. Upper panel, brightfield images of tumor and tumor bed. Lower panel, the corresponding fluorescence images. Images are representative of 4 mice/group. (B) Comparison of the tumor-to-background ratio of the fluorescence signal obtained during IGS of P-GFLG-Cy5 (red) and ProSense® 680 (gray) 4 h (left) and 24 h (right) post i.v. injection (*p= 0.029 and 0.049, respectively, two-tailed t-test). Data represent mean ± SD (n=3-5). (C) Comparison between P-GFLG-Cy5 and ProSense® 680 4 h (left panel) and 24 h (right panel) post i.v. injection for image-guidance. Left panel: surgical field representative images of P-GFLG-Cy5 (1, 3) vs. ProSense® 680 (2, 4) 4 h post administration. Right panel: surgical field representative images of P-GFLG-Cy5 (5, 7) vs. ProSense® 680 (6, 8) 24 h post administration. Fluorescence images were obtained using the CRI MaestroTM imaging system. Filter set: λEx: 635 nm or 665 nm, λEm: 650-800 nm or 680-800 nm, filter: 675 nm or 700 nm for P-GFLG-Cy5 or ProSense® 680, respectively. Images are representative of 3 mice/group.

The tumor delineated with Cy5 fluorescence signal was resected until only a noise signal was detected in the surrounding tissue. Furthermore, we compared our probe's performance as an IGS tool to three control groups: the first group underwent surgery under white light illumination only; the second group underwent IGS by the commercially available polymeric system ProSense® 680; the third group underwent IGS post oral administration of the FDA-approved 5-ALA. ProSense® 680, composed of PEGylated poly-L-lysine residues bearing self-quenched Cy5.5 fluorescent molecules, possesses a MW of ~400,000 Da and its ideal imaging time is reported to be ~24 h post i.v. administration 33. Hence, it might be less desirable for image-guided surgery purposes, since additional hospitalization days may be required. To compare between the two probes for imaging during surgical procedures, we evaluated their kinetics following i.v. injection (Figure S10A-B). At 4 h post i.v. administration, ProSense® 680 tumor-to-background ratio was lower in comparison to the P-GFLG-Cy5 (Figure 6B, left panel). Moreover, 24 h post i.v. injection, which is the suitable Turn-ON time reported and observed for ProSense® 680, its tumor-to-background ratio was also lower in comparison with P-GFLG-Cy5 imaged at the same time point (Figure 6B, right panel). We performed image-guided surgeries using both probes, at their suitable time points, 24 h and 4 h (Figure 6C). Although ProSense® 680 generated a higher signal from the tumor compared to the P-GFLG-Cy5, it also produced a higher background signal (Figure S10A-B). High signal from the tumor may be preferable for imaging of enzyme activity at the tumor; however, for IGS purposes, the improvement of tumor-to-background ratio is highly desirable in order to distinguish between healthy and cancerous tissue. The third group underwent IGS by 5-ALA 4 h post oral administration (0.1 mg/g) (Figure S10C). Tumor survival curves demonstrated prolonged survival for the mice who underwent IGS by P-GFLG-Cy5 guidance in comparison with 5-ALA or ProSense® 680 groups (Figure S10D).

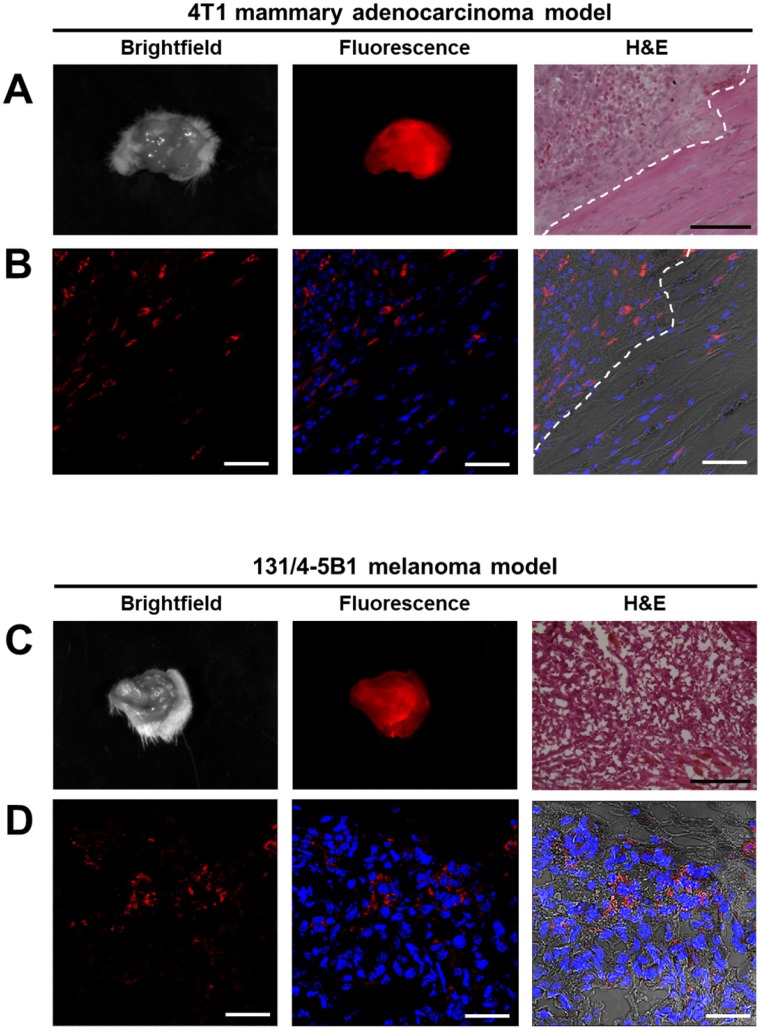

Histological analysis of surgical specimens derived from the surgery guided by P-GFLG-Cy5 or PCQ Turn-ON probes

The fluorescent lesions, suspected to be cancerous tissues that were resected 4 h and 24 h post i.v. injection of P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ Turn-ON probes' fluorescence were imaged ex-vivo by the CRI MaestroTM imaging system. Brightfield images and Cy5 fluorescence signal detected in the excised tumors of breast and melanoma models are presented in Figure 7A, C. Next, malignancy analysis of these excised 4T1 and 131/4-5B1 tissues by H&E staining confirmed that the tissues are indeed cancerous lesions (Figure 7A, C, right panel). Furthermore, in order to follow P-GFLG-Cy5 and PCQ uptake by cells in the tumor area, adjacent sections were fixed with PFA, mounted with DAPI and Cy5-positive signal was evaluated. As expected, the fluorescence signal, resulting from the Turn-ON probes, (red) was detected inside the cells in the tumor region (Figure 7B, D). In addition, we found that the tumor tissue showed an increased fluorescence signal in comparison with normal mammary tissue (Figure S9A-C). As expected, upon i.v. administration of P-GFLG-Cy5 to healthy mice, only background signal level was observed (between 0.4-2 relative scaled counts/s, Figure S9D-E). These results indicate that our probes are indeed efficient for specifically labeling tumor tissue during surgery.

Figure 7.

Imaging and histology of resected tumors showing a representative region from the 4T1 (upper panel) and 131/4-5B1 (lower panel) xenografts injected with P-GFLG-Cy5 or PCQ (respectively) and excised by their guidance. (A, C) Brightfield and Cy5 imaging of whole excised tumor. Left: for confirmation of pathological regions identified using the probe fluorescence, serial 10 µm OCT sections were stained with H&E. P-GFLG-Cy5 (B) and PCQ (D) fluorescence (red) was detected inside the cells in the tumor area in both breast and melanoma models, respectively. White scale bars are 50 µm. Black scale bars are 200 µm. Paired H&E staining was performed to localize regions of disease. Images of resected tumors are representative of 4 mice. OCT sections are representative of 3 fields-of-view for both H&E and DAPI staining.

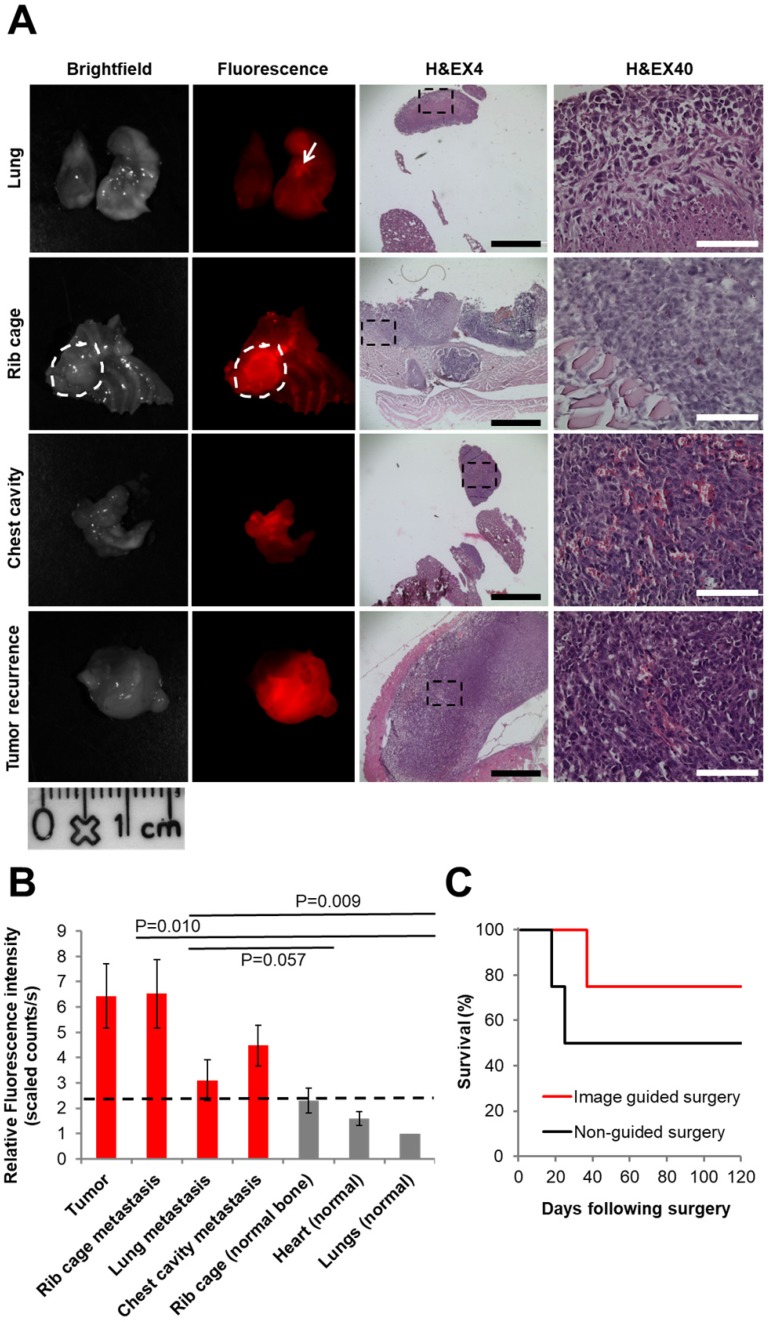

Tumor recurrence follow-up after surgical resection

The P-GFLG-Cy5 IGS group and the non-guided surgery group (control) were surveilled for tumor and/or metastases recurrence, weight change, and overall survival for 17 weeks. The group that underwent non-guided surgery demonstrated a reduced survival rate and had tumor and metastasis recurrence earlier then the IGS group (18 and 25 days vs. 37 days, respectively; Figure 8C). The first mouse that showed a sharp weight loss, at 18 days post-surgery, underwent imaging using CRI MaestroTM. In order to identify the tumor recurrence non-invasively, P-GFLG-Cy5 probe was injected i.v. (10 µM Cy5-eq. concentration, 200 µL); four hours later, the mouse was anesthetized and imaged. The mammary adenocarcinoma tumor was detected non-invasively by fluorescence Cy5 signal. Later, we validated these findings searching for metastases post-mortem. All glowing spots, suspected as metastases, and tumor were excised, imaged and examined by H&E staining. Two additional mice from the non-guided surgery group and the IGS group had tumor and metastasis recurrence at days 25 and 37, respectively, and were evaluated in the same manner for metastasis burden by our Turn-ON probe imaging post-mortem. Figure 8A brightfield and fluorescence imaging show representative tumor recurrence and metastasis spread to the lungs, rib cage and into the chest cavity. The tissues were removed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 5 µm sections and stained using H&E to confirm malignancy (Figure 8A, right). As expected, the malignant tissues had a higher fluorescence signal, resulting from higher uptake, retention and Turn-ON ability of the probe (as shown in vitro). An average signal of between 1-2.3 relative scaled counts/s was observed for the healthy surrounding tissues in comparison with 3.1-6.5 relative scaled counts/s for the metastases within them (Figure 8B). The difference between the signal obtained from cancerous and healthy tissues was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05 between the tumor or metastases in the rib cage to the signal from healthy lungs). Thus, we demonstrate our probe is able to identify small metastases spread among healthy tissues, with a clear cut-off differentiation from the healthy tissue (dashed black line at ~2.3 relative scaled counts/s). The difference of the average fluorescence signal between the metastases in the rib cage to the normal lungs was statistically significant (p=0.010), and near statistically significant in comparison with normal rib cage bone (p=0.57). In the case of lung metastases, there was no statistical significance in comparison to normal tissues, which can be explained by the necrosis revealed by H&E staining (Figure 8A, upper panel).

Figure 8.

Comparison between IGS and non-IGS groups. (A) Tumor recurrence 18 days post standard surgery. Left panel: brightfield. Middle panel: visualization by P-GFLG-Cy5 signal (red) in tumor tissue and metastases, using CRI MaestroTM imaging system. Right panel: H&E staining of the tumor and metastases in the different organs (lungs, chest cavity and rib cage). Red signal obtained in the tumor and metastases was confirmed in the H&E staining. Black and white scale bars represent 1000 and 100 µm, respectively. (B) Uptake of P-GFLG-Cy5 4 h post i.v. injection to healthy vs. cancerous tissues. Fluorescence signal detected from different organs 4 h post i.v. injection of P-GFLG-Cy5 (10 µM, 200 µL). The difference between signal from tumor and rib cage metastases to the normal lung was statistically significant (one-way ANOVA). (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Tumor-free survival after surgery vs. time (days) for 4T1 mammary adenocarcinoma mice (n = 4 for P-GFLG-Cy5 guidance, n = 4 for non-guided surgery) showing improved long-term tumor-free survival with P-GFLG-Cy5 guidance (red) compared to non-guided surgery (black), performed under white light illumination only. Images are representative of 3 mice with tumor and metastases recurrence. H&E images are representative of 3 fields-of-view for each section.

Discussion

There is an unmet need for advanced technology and tools to better delineate tumor boundaries in real-time during surgery for complete tumor excision. This may reduce the risk for tumor recurrence, repeated surgeries and improve post-surgery quality of life due to minimal harm to healthy tissue. In addition, it may hopefully lead to improved patient survival rates. Fluorescence imaging is a highly beneficial technique for real-time assessment of tumor boundaries during surgical procedures and holds many advantages. Apart from the relatively low cost of the fluorescent contrast agent, it is considered to be safe for the patient and for the medical team, generates high signal upon activation, and can be designed to be activated through certain molecular pathways. Thus, it can be tailored to the patient according to their specific biomarkers in a personalized manner. Furthermore, use of fluorophores in the far-red range or above leads to an improved depth of penetration and reduced scattering of light, thus allowing visualization of cancer cells up to 0.5 cm depth 17. From the surgeon's point of view, with this beneficial depth range, the cancerous tissue in the surgical field would not be apparent except by looking through special goggles or at a screen. Thus, the surgeons could decide how much tumor to remove both by white light and palpitation as they are used to, while validating that no cancer cells are missed in real time by looking at the fluorescence signal on a screen or special goggles.

In this study, we report the design, synthesis and characterization of three novel polymeric, cathepsin-activatable, Turn-ON probes (Figure 1A-B). Using two different polymeric systems with diverse Turn-ON mechanisms, we sought to study how the difference in the site of degradation by cathepsins (polymeric backbone vs. substrate linker) and the size alter their in vitro and in vivo performance. We showed in this study that the size may influence the time to start the IGS post i.v. injection in vivo, which was 4 h vs. 24 h when using the larger particle. In addition, we compared the first generation polymeric “smart” probe 33, now commercially available as ProSense® 680 (PerkinElmer Inc.), to our P-GFLG-Cy5 probe. As expected, the commercial agent displayed prolonged accumulation and a slower Turn-ON time in the tumor of ~24 h post i.v. administration (Figure S10A). This prolonged time might be attributed to the larger MW of ProSense® 680, reported to be ~400,000 Da. This might be less preferable for surgical resection applications, from an economic point of view, requiring unnecessary in-patient days. The P-GFLG-Cy5 Turn-ON probe generated maximal NIRF signal ~4 h post i.v. administration. In addition, its hydrodynamic diameter of ~7 nm, which is below 10 nm, is within the suitable size range of probes used for IGS 52 that is reflected by the latest agents evaluated in clinical trials 40, 70. This size is large enough to accumulate in the tumor and maintain there during the operation and imaging, and small enough to be cleared from the circulation. Although a probe's macromolecule size and physical properties mainly affect the time it takes to accumulate in the tumor, it should be taken into consideration that the enzymatic catalytic efficiency (Kcat/KM) of CTSB to the Turn-ON probes may also affect their Turn-ON fluorescence signal. Thus, the difference in enzymatic efficiency of our Turn-ON probes was evaluated in vitro. The calculated catalytic efficiency was higher for P-GFLG-Cy5 (Figure 4C-D), indicating that CTSB and GFLG form a stronger bound complex, with faster turnover (degradation) rate compared to the PCQ probe. This finding was additional to its faster in vivo tumor accumulation in comparison with PCQ, presumably due to its lower hydrodynamic diameter (Table 1). Alternative fluorescently activatable imaging probes for image-guided surgery or for tumor imaging that are based on FRET have been recently published. The FRET pair composed of two NIR dyes, whose fluorescence signal changes upon activation, thus the activation is detected in a second step by ratiometric image analysis 71, 72. While these reports demand further image analysis, which is time-consuming and also currently unavailable for real-time procedures, our system showed a Turn-ON capacity of about 3-fold change, using a simpler system bearing one kind of dye, which is paramount for clinical translation. Our probes were designed to possess optimal dye loading for enzymatic cleavage and Turn-ON ability (Figure 2C and Figure 4A). In addition, our diagnostic system is non-targeted, and the increase in the fluorescence signal in the tumor site results from the Turn-ON activation (Figure 4A-B), the EPR effect, and the improved signal from cancerous cells altogether (Figure 5A-D). The addition of a targeting moiety adds complexity to the system in terms of synthesis, characterization and reproducibility, which hamper translation to the clinic 73. Moreover, the advantages of targeting agents on macromolecules are still debatable, and reports show similar delivery for both targeted and non-targeted macromolecules. 74-76.