Abstract

Introduction

This study examines the associations between early onset of e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors among US adolescents.

Methods

Data were collected via self-administered questionnaires from a nationally representative sample of 2299 US high school seniors attending public and private high schools during the spring of their senior year in 2015 as part of the Monitoring the Future study.

Results

A higher percentage of adolescents who began using e-cigarettes in ninth grade or earlier (early onset) were found to report current and lifetime cigarette smoking and other substance use relative to those individuals who never used e-cigarettes or those who began using e-cigarettes later in the 12th grade. Multivariate logistic regression analyses indicated that the adjusted odds of alcohol use, cigarette smoking, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use, and other illicit drug use among early onset e-cigarette users were significantly greater than those for individuals never having used e-cigarettes (adjusted odds ratios [AORs] ranged 9.5–70.6, p < .001). While these associations were significant for both experimental and frequent e-cigarette users, the effects of early onset were stronger among frequent e-cigarette users. Similarly, the odds of these substance use behaviors (except alcohol) among early onset e-cigarette users were also significantly greater than the odds for later onset e-cigarette users (AORs ranged 2.8–4.1, p < .05).

Conclusions

Early onset of e-cigarette use was significantly associated with increased odds of cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors. E-cigarette use is often preceded by alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and marijuana use, suggesting that more long-term prospective studies are warranted.

Implications

To date, no studies have examined the probability of cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors as a function of age at onset of e-cigarette use. In the present study, early onset of e-cigarette use was significantly associated with increased odds of cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors. The findings reinforce the importance of addressing a wide range of substances including alcohol, traditional cigarettes, and marijuana when developing early primary prevention efforts to reduce e-cigarette use among youth.

Introduction

E-cigarette use has generally increased in recent years among US adolescents, emerging as a potential public health concern.1–4 While past-month e-cigarette use among US high school students increased from 1.5% to 16.0% between 2011 and 2015,4 a recent decrease was found in e-cigarette use between 2015 and 2016 among secondary school students.1,2 E-cigarettes have the lowest perceived risk for regular use relative to any other psychoactive substance among adolescents.1 Despite this very recent decline, adolescents’ e-cigarette use (any lifetime and past-month use) in the United States remains more prevalent than any single nicotine or tobacco product, including traditional cigarette smoking.1,4 Notably, current regular use of e-cigarettes is more prevalent than current regular use of traditional cigarettes among US 8th and 10th grade students, while the prevalence of current regular use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes was the same among 12th grade students.2 However, prevalence estimates for e-cigarette/vaporizer use can be misleading since many adolescents report using “just flavoring” the last time they used an e-cigarette/vaporizer and some of these individuals may have never used nicotine.1,5 Despite the fact that e-cigarette use is associated with higher odds of subsequent cigarette smoking, more than a quarter million adolescent e-cigarette users have no history of cigarette smoking or other tobacco use.6–11 To date, there is a gap in knowledge regarding the associations between early onset of e-cigarette use and the initiation of cigarette smoking as well as other substance use behaviors.

Alcohol and nicotine are often the first psychoactive substances adolescents experiment with, and use of these substances often precede use of marijuana and other illicit drugs.12 Early onset of substance use is especially important because of its association with increased risk of the development of alcohol and other drug-related problems.13–16 Previous research has shown that individuals who begin drinking before age 15 are more likely to develop alcohol use disorders in their lifetime than those who begin drinking later in life.14 Similarly, early onset of marijuana and nonmedical prescription drug use is a significant risk factor for the subsequent development of adult (or lifetime) drug-related problems and drug use disorders.15,16

There is also preliminary evidence demonstrating an increased risk for substance use behaviors among e-cigarette users.17–19 Adolescents who use the four most common substances of abuse (eg, alcohol, marijuana, tobacco cigarettes, and prescription drugs) account for over 80% of e-cigarette users in 12th grade.18 However, to our knowledge, no studies have differentiated between early and later onset of e-cigarette use, and no studies have examined the order of initiation involving the onset of e-cigarette use and a wide range of substance use behaviors. Existing findings are limited with respect to the age at onset of e-cigarette use and its implications for other substance use behaviors. As of yet, no studies have examined the probability of other cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors as a function of age at onset of e-cigarette use. The primary aim of this study was to examine the relationships between early onset of e-cigarette use and the prevalence of substance use behaviors in a nationally representative sample of US high school seniors.

Methods

Data

The present study analyzed data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study, which annually surveys a cross-sectional, nationally representative sample of high school seniors in approximately 125 public and private schools in the coterminous United States, using self-administered paper-and-pencil questionnaires in classrooms. The samples analyzed in this study consisted of high school seniors from the 2015 cohort. The MTF study used a multi-stage sampling procedure. Stage 1 is the selection of geographic areas within the four regions of the country including the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. Stage 2 is the random selection of approximately 130 public and private high schools with replacement (schools that decline are replaced with schools that are similar on geographic location, size, and urbanicity). Stage 3 is the selection of students within each school. Corrective weighting was used in the analyses presented in this study to account for the unequal probabilities of selection that occurred at any stage of sampling.

The response rate in the MTF study for high school seniors was 83% in 2015. Because so many questions are included in the MTF study, much of the questionnaire content is divided into six different questionnaire forms which are randomly distributed to students. This approach results in six identical subsamples. The measures most relevant for this study were asked on form 1, so this study focuses on the cross-sectional subsamples receiving this form. Additional details about the MTF design and methods are available elsewhere.1,2 Institutional Review Board approval was granted for this study by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The MTF study assesses a wide range of variables relevant to e-cigarette use. For the present study, we selected specific measures for analyses, including demographic characteristics and standard measures of substance use behaviors.1,2Demographic and background characteristics included sex, age (less than 18 years old or 18 years and older), race/ethnicity (Black, White, Hispanic, Other), US Census geographical region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), metropolitan statistical area (MSA) (large, other, non-MSA), parental education (some college vs. high school or less), and college plans (any plans to attend college vs. no plans to attend college).

E-cigarette use was assessed by asking respondents how many occasions (if any) they had used e-cigarettes in their lifetime and in the past 30 days. The lifetime response options ranged from (1) never to (5) regularly, and the 30-day response options ranged from (1) none to (6) 20–30 days. Both response scales were dichotomized (any use/no use) for purposes of analyses consistent with previous research.1,2,18Age of onset for e-cigarette use was assessed by asking respondents what grade level they first used e-cigarettes. The response options ranged from (1) never to (7) grade 12. For purposes of analyses, a five-level variable was created with the following categories: never, grade 12, grade 11, grade 10, and grade 9 or earlier.

Cigarette smoking was assessed by asking respondents how often (if any) they had smoked cigarettes in their lifetime and in the past 30 days. The lifetime response options ranged from (1) never to (5) regularly, and the 30-day response options ranged from (1) none to (7) two packs or more per day. Both response scales were dichotomized (any use/no use) for purposes of analyses consistent with previous research.1,2,18Alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use—including cocaine, LSD, psychedelics other than LSD, and heroin—were measured by asking respondents how many occasions (if any) they used [each specified drug] in their lifetime and in the past 30 days. The response scale for each of these items ranged from (1) no occasions to (7) 40 or more occasions, and were dichotomized (any use/no use) for purposes of analyses consistent with previous research.1,2,18Nonmedical prescription drug use was assessed by asking respondents on how many occasions (if any) they used each prescription drug class (opioids, stimulants, tranquilizers) on their own, without a doctor’s orders in their lifetime and during the past 30 days. The response scale for each of these items ranged from (1) no occasions to (7) 40 or more occasions, and were dichotomized (any use/no use) for purposes of analyses consistent with previous research.1,2,18Age of onset for substance use behaviors was assessed with separate items for other substance use behaviors (ie, traditional cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, LSD, psychedelics other than LSD, opioids, sedatives, stimulants, and tranquilizers) and the response options for each item were the same as age of onset for e-cigarette use.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses for this study were design-based in nature, fully accounting for the MTF sampling weights in estimation of parameters for the target MTF population and incorporating estimates of MTF design effects (reflecting the complex sample design features) in variance estimates, confidence intervals, and test statistics.20 We initially computed descriptive estimates of selected parameters representing the prevalence of particular behaviors (eg, lifetime e-cigarette use), and then compared different subgroups of individuals based on the grade at which they initiated e-cigarette use in terms of the prevalence of each other substance use behavior. We then performed design-adjusted bivariate Rao-Scott F-tests to examine the associations of e-cigarette onset grade and each behavior. All variance estimates for the estimated descriptive parameters and the design-adjusted test statistics incorporated an MTF average design effect of 2.5 for these specific types of behaviors.7 Next, we fitted multivariate logistic regression models using design-based approaches to estimate the associations of e-cigarette onset grade with each behavior after adjusting for the relevant sociodemographic characteristics and other covariates examined in prior work.1,2,4,10,11,18 These analyses incorporated similar design effects using the methodology of West and McCabe.20 Finally, we conducted descriptive analyses of specific onset patterns for the subsamples of individuals indicating polysubstance use behaviors. All analyses employed the -svy- procedures in the Stata software (Version 14).

Results

The sample for this study included 2299 individuals who completed questionnaires during the spring of their senior year in 2015. After applying the MTF sampling weights, the sample represented a population that was 50% female (based on respondents with no missing data on gender), 48% White, 13% African American, 16% Hispanic, and 23% other/not disclosed. The modal age of the individuals in the sample was 18 years of age.

An estimated 30% of US high school seniors were lifetime e-cigarette users. There were no significant differences in the lifetime prevalence of e-cigarette use between those less than 18 years old (29.5%) compared to those who were 18 years or older (31.5%, p = .43). Among lifetime e-cigarette users, approximately 10% initiated use in grade 9 or earlier, 21% initiated use in grade 10, 43% initiated use in grade 11, and 26% initiated use in grade 12. The prevalence rates of current and lifetime cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors (ie, alcohol use, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use, and other illicit drug use) were examined for each grade level at onset from grade 9 and earlier to grade 12. Among e-cigarette users, the prevalence of current and lifetime cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors was higher among early initiators of e-cigarettes. Grade level of onset had a significant (p < .001) association with cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors, with those having an earlier grade of onset being consistently more likely to report current and lifetime cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors.

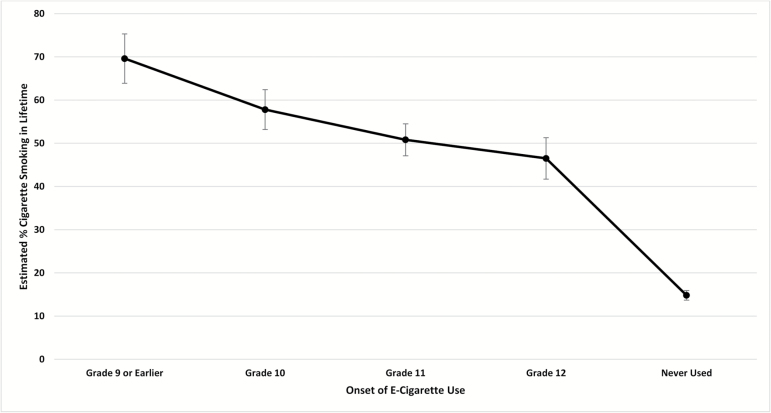

As illustrated in Figure 1, the prevalence of lifetime cigarette smoking increased significantly as a function of lower age at onset of e-cigarette use [Rao-Scott F(df1 = 4.0, df2 = 7938.3) = 26.3, p < .001]. Specifically, approximately 69.6% (SE = 8.1) of those who initiated e-cigarette use at grade 9 or earlier reported any cigarette smoking as compared to 46.5% (SE = 6.4) of the respondents who initiated e-cigarettes in 12th grade and 14.8% (SE = 1.5) of those respondents who never used e-cigarettes. Similarly, the prevalence of lifetime marijuana use increased significantly as a function of lower age at onset of e-cigarette use [Rao-Scott F (df1 = 3.9, df2 = 7787.4) = 29.9, p < .001). Approximately 85.7% (SE = 6.2) of those who initiated e-cigarette use at grade 9 or earlier reported any marijuana use as compared to 56.3% (SE = 6.4) of the respondents who initiated e-cigarettes in 12th grade and 26.9% (SE = 1.9) of those respondents who never used e-cigarettes. Similar associations were found for the prevalence of alcohol use, other illicit drug use and nonmedical prescription drug use as a function of age at onset of e-cigarette use.

Figure 1.

Estimated cigarette smoking prevalence as a function of age of onset of e-cigarette use, 2015. Error bars indicate ±1 SE.

The multivariate logistic regression analyses reinforced the bivariate results and indicated that the adjusted odds of current and lifetime cigarette smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use, and other illicit drug use among early onset e-cigarette users were significantly greater than the odds for those who had never used e-cigarettes. As illustrated in Table 1, the adjusted odds of lifetime cigarette smoking among early onset e-cigarette users were over 14 times greater than those for individuals who never used e-cigarettes (AOR = 14.2, 95% CI = 6.1 to 33.1), after statistically controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and other covariates (AORs ranged from 9.5 to 70.6 for other substance use behaviors).

Table 1.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Results for Cigarette Smoking and Other Drug Use Among the Full MTF Sample, 2015

| Lifetime cigarette smoking (full sample), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime Alcohol Use (full sample), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime Marijuana Use (full sample), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime nonmedical prescription drug useb (full sample), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime other illicit drug usec (full sample), AOR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette use onset | |||||

| Never used | — | — | — | — | — |

| Grade 12 | 5.11 (2.90 to 9.02)*** | 6.06 (2.52 to 14.59)*** | 3.81 (2.20 to 6.62)*** | 3.21 (1.57 to 6.55)** | 4.41 (1.51 to 12.91)** |

| Grade 11 | 6.88 (4.30 to 10.99)*** | 5.85 (3.01 to 11.34)*** | 7.22 (4.50 to 11.57)*** | 5.48 (3.19 to 9.44)*** | 6.63 (2.93 to 15.03)*** |

| Grade 10 | 9.41 (5.16 to 17.17)*** | 26.15 (5.08 to 134.7)*** | 16.36 (7.58 to 35.29)*** | 6.34 (3.27 to 12.28)*** | 7.98 (3.12 to 20.43)*** |

| Grade 9 or earlier | 14.21 (6.10 to 33.11)*** | 70.6 (2.0 to 2434.6)*** | 16.40 (5.87 to 45.79)*** | 9.47 (4.30 to 20.86)*** | 19.23 (7.60 to 48.66)*** |

| Sample sizesd | 1994 | 1980 | 1997 | 1939 | 1905 |

— indicates reference group.

aAll analyses incorporate a design effect of 2.518 and control for age (ie, less than 18 years old and 18 years and older), race (ie, White, Black, Hispanic, Other race), sex (ie, male and female), highest level of parental education (ie, at least some college, high school or less), US Census geographic region (ie, Northeast, Northcentral, South, and West), metropolitan statistical area (ie, MSA and non-MSA), and college plans (ie, plan to attend college and no plans to attend college).

bNonmedical prescription drug use consisted of nonmedical prescription opioid use, nonmedical prescription sedative use, nonmedical prescription stimulant use, or nonmedical tranquilizer use.

cOther illicit drug use consisted of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), other hallucinogens, cocaine, or heroin.

dSample sizes vary due to missing data on the dependent measures (ie, lifetime cigarette smoking, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use, other illicit drug use).

**p < .01, ***p < .001.

We repeated the age of onset analysis distinguishing between experimental e-cigarette users (1–2 times in their lifetime) and more regular lifetime e-cigarette users, and found that early onset for either experimental or more regular users was associated with significantly greater odds of cigarette smoking and most other substance use behaviors (results not shown, and available upon request). Notably, the estimated increases in the odds of the various substance use behaviors as a function of age of onset were generally much larger for the more regular users. For example, the estimated odds of ever engaging in cigarette smoking were over 27 times higher (relative to those who never initiated e-cigarette use) for more regular e-cigarette users who began using e-cigarettes in grade 9 or earlier (95% CI = 7.5 to 100.51; p < .001), while the estimated odds of engaging in the same behavior for experimental e-cigarette users were nearly eight times higher relative to never users (95% CI = 1.4 to 43.0; p < .05).

As illustrated in Table 2, the odds of cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors (with the exception of alcohol use) among early onset e-cigarette users were also significantly greater than the odds for later onset e-cigarette users, after controlling for covariates (AORs ranged from 2.8 to 4.1). For instance, the odds of any marijuana use among early onset e-cigarette users were nearly four times greater than the odds for those individuals who reported later e-cigarette onset in 12th grade (AOR = 3.9, 95% CI = 1.2 to 12.7), after controlling for the covariates.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Results for Cigarette Smoking and Other Drug Use Among E-cigarette Users Only, 2015

| Lifetime cigarette smoking (e-cigarette users), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime alcohol use (e-cigarette users), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime marijuana use (e-cigarette users), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime nonmedical prescription drug useb (e-cigarette users), AOR (95% CI)a | Lifetime other illicit drug usec (e-cigarette users) AOR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade at first e-cigarette use | |||||

| Grade 12 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Grade 11 | 1.38 (0.71 to 2.68) | 0.89 (0.29 to 2.79) | 1.82 (0.93 to 3.56) | 1.70 (0.77 to 3.73) | 1.41 (0.48 to 4.16) |

| Grade 10 | 1.89 (0.87 to 4.09) | 4.02 (0.53 to 30.31) | 3.87 (1.55 to 9.65)** | 1.87 (0.79 to 4.46) | 1.66 (0.51 to 5.43) |

| Grade 9 or earlier | 2.83 (1.06 to 7.51)* | 12.52 (0.91 to 171.5) | 3.91 (1.21 to 12.65)* | 2.90 (1.10 to 7.67)* | 4.07 (1.28 to 12.99)* |

| Sample sizesd | 648 | 644 | 645 | 629 | 624 |

— indicates reference group.

aAll analyses incorporate a design effect of 2.518 and control for age (ie, less than 18 years old and 18 years and older), race (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, Other race), sex (ie, Male and Female), highest level of parental education (ie, at least some college, high school or less), US Census geographic region (ie, Northeast, Northcentral, South, and West), metropolitan statistical area (ie, MSA and non-MSA), and college plans (ie, plan to attend college and no plans to attend college).

bNonmedical prescription drug use consisted of nonmedical prescription opioid use, nonmedical prescription sedative use, nonmedical prescription stimulant use, or nonmedical tranquilizer use.

cOther illicit drug use consisted of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), other hallucinogens, cocaine, or heroin.

dSample sizes vary due to missing data on the dependent measures (ie, lifetime nonmedical prescription drug use and lifetime other illicit drug use).

*p < .05, **p < .01.

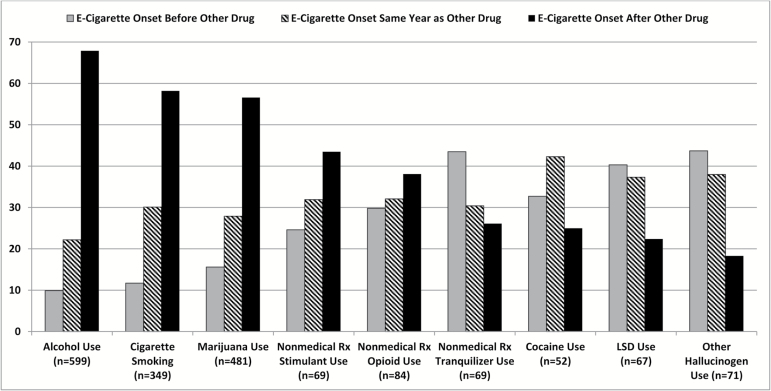

Finally, the patterns of initiation of substance use among lifetime e-cigarette users who engaged in other substance use were examined to determine the temporal order of initiation for e-cigarettes and other substances. As illustrated in Figure 2, e-cigarette users who also reported alcohol use, cigarette smoking, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription stimulant use, or nonmedical prescription opioid use were more likely to initiate each of these substances before e-cigarettes relative to after e-cigarettes. In contrast, a different order was observed for the initiation of e-cigarette use and illicit drugs. E-cigarette users who also reported lifetime use of cocaine, LSD, or other hallucinogens were more likely to initiate each of these substances after e-cigarettes.

Figure 2.

Estimated prevalence of substance use initiation among lifetime e-cigarette users who engaged in other substance use, 2015.

Discussion

To date, studies have not carefully examined the associations among age of onset of e-cigarette use, cigarette smoking, and other substance use behaviors among adolescents.21–23 The findings from the present study provide new evidence that early onset of e-cigarettes is significantly associated with increased odds of cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors relative to those who initiated later e-cigarette use as well as those who did not use e-cigarettes based on a national sample of high school seniors in the United States.

The findings from the present study extend our knowledge of age at onset of e-cigarette use in several important ways. First, the association between early onset of e-cigarette use and other substance use behaviors has remained relatively unexplored. The findings in the present study reinforce previous outcomes related to the role of early onset of alcohol use in association to other substance use behaviors, but extend these relationships specifically to e-cigarette use. Second, previous studies have shown associations between e-cigarette use and other substance use behaviors,17–19 but the present study represents one of the initial examinations of the temporal associations between early onset of e-cigarette use and a wide range of other substance use behaviors. Indeed, the present study found a significant association between age at onset of e-cigarette use and the likelihood of engaging in cigarette smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use. We found that these associations were significant for both experimental and more regular e-cigarette users, and the effects of earlier age of e-cigarette onset tended to be stronger among more frequent e-cigarette users. Third, it is important for future research to consider that the majority of e-cigarette users who engaged in polysubstance use involving alcohol, cigarette smoking, marijuana, nonmedical prescription opioids, or nonmedical prescription stimulants had initiated each of these substances in the same grade level or earlier than that of e-cigarette use onset.

The unique pattern associated with alcohol use among e-cigarette users was largely influenced by alcohol having the earliest average age of onset and highest prevalence rates relative to all the other substances. As a result, 90% or more of all e-cigarette onset subgroups engaged in alcohol use, including over 99% of those reporting early e-cigarette onset. While the cross-sectional design of the current study makes it impossible to determine whether there is a causal relationship and if so, in which direction, between early e-cigarette onset at age 14 or younger and other substance use, our findings clearly indicate the need for future prospective studies aimed at examining the causal relationships between e-cigarette use, cigarette smoking and other substance use.

The findings regarding patterns of initiation were partially influenced by availability, perceived risk, and the average age (grade level) of onset for various substances among adolescents.1,2 For instance, the modal age for e-cigarette use onset is later than the modal age for initiating substances such as alcohol, cigarette smoking, and marijuana. The later modal age for e-cigarette onset could be partially influenced by the fact that e-cigarettes were relatively new on the market among youth and less available during the earlier years of initiation. In contrast, the modal age for e-cigarette onset was before the initiation of illicit drugs such as cocaine and hallucinogens. In addition, the perceived risk of e-cigarette use and vaping was lower before 2015 than at present, and this is likely due to fewer state restrictions on e-cigarette sales by age in previous years and subsequent changes in marketing and federal regulations.1 Among those who reported lifetime e-cigarette use, the subgroup of individuals who initiated e-cigarette use in grade 9 (2012 in expectation) or earlier in the 2015 MTF study was relatively small (10%, n = 93) in the present study, which reduced the power to detect potentially meaningful differences between this onset category and other subgroups (after accounting for MTF design effects). The relatively small early onset subgroup makes the findings related to significantly higher odds of lifetime substance use behaviors for this early onset subgroup relative to those who first used e-cigarettes in grade 12 particularly notable. Taken together, the findings of this study provide evidence that most adolescent e-cigarette users have initiated marijuana or other illicit drug use and should be assessed for polysubstance use behaviors and substance use disorders (SUDs). This is potentially important clinically in SUD treatment algorithms for this vulnerable adolescent population. Specifically, remission from polysubstance use and SUDs has been shown to increase if individuals can also quit nicotine/tobacco use.24–27 This study indicates that abstinence from e-cigarettes as well as tobacco should be considered within a wider range of substances and further studies are needed within the context of relapse recidivism from polysubstance use.

The present study also found that nearly one in every three high school seniors in the United States reported any lifetime e-cigarette use. Notably, e-cigarette use has increased significantly in recent years among adolescents in the United States followed by a recent decline between 2015 and 2016.1,2,4 The initiation patterns observed in the present study support middle school or earlier as optimal timing for delivering preventative interventions to reduce substance use behaviors among youth.28 Finally, as e-cigarettes have only recently come under federal oversight, public health considerations can also be given to the limitation of marketing and advertisement to youth of this multi-billion dollar industry.

The present study has several strengths. A major strength of the present study is the national sample of adolescents with a diverse range of sociodemographic characteristics. The MTF study includes a nationally representative sample of high school seniors from private and public schools in the United States. The sample size allowed for subgroups to be defined based on grade of onset of e-cigarette use and other substance use behaviors.

Despite these strengths, this study had all of the limitations associated with school-based survey research using self-administered surveys and retrospective assessment, including nonresponse bias and missing data. First, the multivariate logistic regression models to estimate the associations of e-cigarette use onset grade with each substance use behavior did not adjust for some relevant variables associated with cigarette smoking and other substance use behaviors (eg, family history of cigarette smoking and substance-related problems) because these variables were not assessed in the MTF study. Additionally, future research is needed to examine the effects of nicotine concentration levels, dose delivered, and frequency of e-cigarette/vaporizer use since a considerable proportion of adolescents do not know the nicotine concentration in their e-cigarettes/vaporizers. Previous work has often been limited to assessing only the most recent e-cigarette/vaporizer use occasion.1,5,29 Second, there were some important subgroups of the adolescent population missing from the MTF data collected each year, such as students who were home-schooled, have dropped out of school, or were absent on the day of data collection and therefore did not participate in the study. High school students who drop out or who are often absent from school are more likely to engage in substance use and other problem behaviors,2,30 while home-schooled youth are less likely to engage in substance use behaviors.31 Third, while prior work has demonstrated that self-report data in the MTF study have been found to be reliable and valid, studies on adolescents suggest that misclassification and under-reporting of sensitive behaviors such as substance use can occur.32,33 The MTF study attempted to minimize the bias associated with self-report surveys by utilizing certain conditions that past research has shown improves the validity and reliability of substance use data collected via self-report surveys, such as explaining the relevance of the study and informing potential respondents that participation is voluntary and data will remain anonymous.33 In the MTF study, no adjustments are made to correct for any missing data or under-reporting; thus, results from the present study are likely conservative and underestimate substance use behaviors. Finally, the present study relied heavily on dichotomous substance use behaviors (any use/no use), and future research is recommended that examines frequency of e-cigarette/vaporizer use, cigarette smoking and other substance use relationships in more detail.

The findings of the present study reinforce the importance of learning more about the short-term and long-term consequences associated with e-cigarette use, especially with early onset (aged 14 and younger). Recent findings indicate adolescents are much more likely to use e-cigarettes/vaporizers for experimentation, taste, and boredom, whereas adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes for smoking cessation.34–36 Because e-cigarettes have the lowest perceived risk for regular use relative to any other substance among adolescents, traditional models that explain the onset and course of use for substance use behaviors may not completely apply to e-cigarette use. There have been several attempts with adults to examine whether e-cigarettes can help cigarette smokers reduce their tobacco smoking or help them change to less hazardous tobacco products.37–45 Although the present study indicated most adolescents initiated e-cigarettes after cigarette smoking, recent work indicates less than 1 in every 13 adolescents who use e-cigarettes or vaporizers are motivated for smoking cessation reasons.34 Additionally, a recent study found evidence that e-cigarette use is a stronger risk factor for smoking onset among low risk relative to high risk adolescents.46 Thus, if future work confirms early e-cigarette onset leads to cigarette smoking, e-cigarette use may pose considerable challenges for the substance abuse field and efforts to reduce health consequences associated with smoking given the low perceived risk.1,2,47,48

The findings of the present study clearly indicate the need for more long-term prospective and multi-cohort studies to examine similar age-of-initiation relationships between e-cigarette use and other substance use behaviors among children and adolescents. The high rates of polysubstance use associated with early onset of e-cigarette use reinforce the importance of developing early primary prevention efforts to reduce or delay harmful substance use behaviors among children and adolescents.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA203809 and R01CA212517) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA031160 and R01DA036541) at the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no additional role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. There was no editorial direction or censorship from the sponsors.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Monitoring the Future data were collected under research grant R01DA001411 and the authors would like to thank the National Addiction & HIV Data Archive Program for providing access to these data. The authors would like to thank the respondents and school personnel for their participation in the study. The authors would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers and editorial staff for their suggestions to a previous version of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE.. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use: 1975–2016: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2017. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2016.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE.. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use: 1975–2015: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2016. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2015.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_SGR_Full_Report_non-508.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361–367. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. Accessed December 1, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Glasser AM et al. Frequency of youth e-cigarette and tobacco use patterns in the U.S.: measurement precision is critical to inform public health. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;. in press. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntw388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corey C, Wang B, Johnson SE et al. Notes from the field: electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(35):729–730. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24005229. Accessed October 1, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among U.S. adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(7):610–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA et al. Associations between e-cigarette access and smoking and drinking behaviours in teenagers. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, Sargent JD. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among us adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory. J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53(5):447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10(2):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCabe SE, West BT, Morales M, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ. Does early onset of non-medical use of prescription drugs predict subsequent prescription drug abuse and dependence? Results from a national study. Addiction. 2007;102(12):1920–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kristjansson AL, Mann MJ, Sigfusdottir ID. Licit and illicit substance use by adolescent e-cigarette users compared with conventional cigarette smokers, dual users, and nonusers. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(5):562–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Patrick ME. E-cigarettes and the drug use patterns of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):654–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Unger JB, Soto DW, Leventhal A. E-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette and marijuana use among Hispanic young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:261–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. West BT, McCabe SE. Incorporating complex sample design effects when only final survey weights are available. Stata J. 2012;12(4):718–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Collaco JM, Drummond MB, McGrath-Morrow SA. Electronic cigarette use and exposure in the pediatric population. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(2):177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drummond MB, Upson D. Electronic cigarettes. Potential harms and benefits. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baca CT, Yahne CE. Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: what you need to know. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(2):205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lemon SC, Friedmann PD, Stein MD. The impact of smoking cessation on drug abuse treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 2003;28(7):1323–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCarthy WJ, Zhou Y, Hser YI, Collins C. To smoke or not to smoke: impact on disability, quality of life, and illicit drug use in baseline polydrug users. J Addict Dis. 2002;21(2):35–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Satre DD, Kohn CS, Weisner C. Cigarette smoking and long-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes: a telephone follow-up at five years. Am J Addict. 2007;16(1):32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Griffin KW, Botvin GJ. Evidence-based interventions for preventing substance use disorders in adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(3):505–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morean ME, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Nicotine concentration of e-cigarettes used by adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:224–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, Kremer KP, Maynard BR, Roberts G, Vaughn S. Are homeschooled adolescents less likely to use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs?Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harrison L, Hughes A. Introduction—the validity of self-reported drug use: improving the accuracy of survey estimates. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;167:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Reliability and consistency in self-reports of drug use. Int J Addict. 1983;18(6):805–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Patrick ME, Miech RA, Carlier C, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Self-reported reasons for vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the US: nationally-representative results. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:275–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction. 2011;106(11):2017–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patel D, Davis KC, Cox S et al. Reasons for current E-cigarette use among U.S. adults. Prev Med. 2016;93:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adriaens K, Van Gucht D, Declerck P, Baeyens F. Effectiveness of the electronic cigarette: an eight-week Flemish study with six-month follow-up on smoking reduction, craving and experienced benefits and complaints. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(11):11220–11248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berg CJ, Barr DB, Stratton E, Escoffery C, Kegler M. Attitudes toward e-cigarettes, reasons for initiating e-cigarette use, and changes in smoking behavior after initiation: a pilot longitudinal study of regular cigarette smokers. Open J Prev Med. 2014;4(10):789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, Michie S, West R. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: a cross-sectional population study. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1531–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9905):1629–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Prevalence of population smoking cessation by electronic cigarette use status in a national sample of recent smokers. Addict Behav. 2018;76:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grana RA, Popova L, Ling PM. A longitudinal analysis of electronic cigarette use and smoking cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):812–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kasza KA, Bansal-Travers M, O’Connor RJ et al. Cigarette smokers’ use of unconventional tobacco products and associations with quitting activity: findings from the ITC-4 U.S. cohort. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(6):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Polosa R, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, Morjaria JB, Russo C. Success rates with nicotine personal vaporizers: a prospective 6-month pilot study of smokers not intending to quit. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu SH, Zhuang YL, Wong S, Cummins SE, Tedeschi GJ. E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys. BMJ. 2017;358:j3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wills TA, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Schweitzer R. E-cigarette use is differentially related to smoking onset among lower risk adolescents. Tob Control. 2016;26(5):534–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44616/1/9789240687813_eng.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.