Abstract

This qualitative research explores the relationship between religiosity, suicide thoughts and drug abuse among 55 homeless people, interviewed with interpretative phenomenological analysis. Analyzing the thematic structure of the participants’ narrations, important main themes appeared in order to avoid suicide, among which family, the certainty of finding a solution and the will to live. However, the suicide ideation inheres in about 30% of participants, almost all believers, addicted and/or alcoholics. Results suggest that religiosity and meaning of death neither prevent from substances abuse and alcoholism, nor is a protective factor against suicide ideation. Meanings of life are the most important reasons for living, and when they are definitively considered unworkable, alcohol and drug help to endure life in the street. A specific model is discussed.

Key words: Suicide, drug addiction, homeless people, religiosity

Introduction

Homeless persons are individuals living in the streets without a shelter because are unable to acquire and maintain regular, safe, and adequate housing, more so when they do not have a lawful access to buildings in which to sleep. Causes of the homeless phenomenon are multiple. Among them, four broad risk factors, which often occur together, increase the probability of those affected becoming homeless: structural, institutional, relational and personal. The first and second ones are related to unemployment and low incomes, the third and fourth refer to biographical difficulties, among which social and personal conflicts, while the subjective factors, which include vulnerability and mental health problems, alcoholism and addictions emerge for importance.1

In Europe, rates of homelessness are getting alarming and worsening dimensions, because of the increased migration due to political instability in Asia, Middle East and Northern Africa.2 Often migrants suffer from homelessness, because of the loss of the social identity and of the supportive network, while the economic difficulties often determine the miscarriage of their existential project.3 All these experiences cause high level of distress and impotence, from which alcohol and drug abuse frequently derive.4 According to some studies, over two-thirds of homeless people abuse alcohol and/or illicit drugs, with this percentage being significantly higher than other social groups. Among them, over two-thirds began to ingest heavy doses of alcohol only after they ended in the street and suffer principally from cognitive disabilities, affective disorders and depression.5,6 On the contrary, those who are not abusing alcohol have a higher level of generalized anxiety and schizophrenic disorders.5-7 Other studies, however, show that the association between alcohol and substance abuse is significant only among homeless youth, adults who suffer from serious health problems (e.g.: cancers that lead to death), war veterans, victim of childhood sexual abuse.7 The problem is particularly important because this population generally has inadequate access to primary health care.8 Indeed its condition often leads to high risk of self-harm and suicide, AIDS, tuberculosis, with mental and physical degradation.9,10 Nevertheless, the association between abuse of alcohol/ rugs and suicidal ideation in these subjects is controversial. Some studies suggest that the suicidal ideation in young homeless is not significantly related to substance abuse, but to previous situations of family violence and/or sexual abuse.11 Other surveys reveal that suicidal ideation is significantly present in those suffering from major depressive disorder, or perceived lack of social support, and not by those who use alcohol or drugs.12

The Terror Management Theory (TMT) and the Identity Theory highlighted the social function of religion as a facilitator of social relationships.13 From the individual point of view, the representation of death as a passage supported by religiosity and spirituality influences personal emotional stability and resilience preventing suicide.14 Additionally, research generally confirms that it supports psychological and somatic health.15,16 The positive impact of religion on preventing suicide and self-injuring behavior have been promoted by three perspective: integration hypothesis; the religious commitment hypothesis and the network hypothesis.17 Indeed, all the most important religions underline the sanctity of life and provide moral norms which respect the value of life, fulfilling the human role in this world whilst maintaining stability, patience and steadfastness in all circumstances. Furthermore, such traditions not only prohibit suicide but also explicitly deter from wishing for death or endanger health and life.18 Besides, religion may create many psychosocial problems as well.19 Then, it seems that it does not support people who are in critical conditions for a long time, since it facilitates the elaboration of past traumas, but cannot help to solve present and persistent difficulties.19

The suicide risk in really higher among homelessness people,20 and their suicide rates typically range from 20% to 40%, while in the general population the rate is 0.9%.21 On the other hand, suicide risk in addicted or alcoholics populations is similarly high.22,23 Despite research on this factor among homelessness people is not yet enough developed, some studies on coping with street-life have already showed how spirituality and religiosity buffersnegative life events.24 On one hand it moderates the levels of anxiety or depression, on the other prevents substance abuse and suicide.24

The present qualitative research analyzed the relationships among meaning of life and death, and how religiosity and alcoholism/drug addiction intervene in suicide ideation.

Aims of this research

As widely evidenced by research, meaning of life and religiosity are protective factors because they can prevent suicide.25 The first aim was to analyze the meaning of life and death through the biographical narrations of people affected by homelessness, in order to recognize the Main Themes (MTs) that characterize their reasons for living. The second aim was to highlight the role of religiosity and addiction in their everyday life. Since drug addiction, self-harm and suicide are strongly condemned by all religions and since these are largely prevalent among homeless people,26 we wanted to analyze whether religiosity and the meaning of death as a passage toward God could be a protective factors against suicide ideation and drug/alcohol addiction or not.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We selected the study population based on the principle of appropriateness, and according to the following criteria: the participants were homeless and able to understand and speak the Italian language, motivated to participate in the dialogue, without severe psychiatric diseases. They were recruited from volunteer associations of 13 cities of Northern, Central and Southern Italian regions. The study followed American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The interviewer, a psychologist expert of communication with homeless people, gave potential participants detailed information regarding the goal of the study and the manner with which the interview would be developed. A verbal request of agreement was proffered. None of them was forced to take part to the study and they could refuse to talk about upsetting issues. In addition, they could withdraw from the interview at any time without explanation or penalty. If they agreed to participate, the interview was conducted immediately, because it was arduous, if not impossible, to schedule a future date. At the end, 55 out of about 600 contacted homeless people participated (49 male and 6 female). Most of them were immigrants from Africa, Asia and East Europe. Twenty-seven participants were Italian. We considered as addicted only those who currently abuse of substances and/or alcohol. Homeless people who had been addicted in the past and those who make only sporadic use of alcohol do not enter into this category (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-anagraphic variables.

| Age | Sex | Nationality | Homeless since | In Italy since | Institutionalization experience | Marital status | Children | Education | Homelessness causes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 40 | M | Moroccan | 2 w | 6 ys | Married | yes | Middle school | Structural | |

| P2 | 55 | M | Moroccan | 3 y | 6 y | Divorced | yes | Polytechnic school | Structural | |

| P3 | 40 | M | Moroccan | 2 m | 8 y | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Structural | |

| P4 | 35 | M | Indian | 3 m | 3 y | Engaged | no | Economy degree | Structural | |

| P5 | 30 | M | Moldavian | 3 w | 6 y | Divorced | yes | Middle school | Structural | |

| P6 | 51 | M | Senegalese | 6 y | 12 y | Divorced | yes | Primary school | Relationship | |

| P7 | 63 | M | Italian | 2 w | - | Divorced | yes | High school | Relationship | |

| P8 | 57 | M | Romanian | 2 m | 10 y | Married | yes | Middle school | Structural | |

| P9 | 32 | M | Italian | 3.5 y | - | Drug Rehab Center | Divorced | yes | Polytechnic school | Relationship / Personal |

| P10 | 27 | M | Tunisian | 1 m | 4 y | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Relationship / Structural | |

| P11 | 58 | M | Italian | 2 m | - | Jail | Divorced | yes | Middle school | Institutional |

| P12 | 45 | M | Moroccan | 1 m | 6 y | Married | yes | Middle school | Structural | |

| P13 | 41 | M | Moroccan | 1 y | 11 y | Jail | Divorced | yes | Middle school | Structural |

| P14 | 47 | M | Moroccan | 2 y | 14 y | Jail | Divorced | yes | Middle school | Institutional |

| P15 | 50 | M | Moroccan | 10 y | 35 ys | Bachelor | no | Law degree | Structural | |

| P16 | 35 | M | Bangladeshi | 2 y | 8 y | Divorced | no | Economy degree | Personal | |

| P17 | 31 | M | Albanian | few m | 20 y | Married | yes | ND | Structural | |

| P18 | 36 | M | Indian | few m | few m | Jail | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Structural |

| P19 | 23 | M | Albanian | few d | 5 m | Jail | Bachelor | ND | ND | Institutional |

| P20 | 50 | F | Italian | 1 y | - | Divorced | yes | ND | Personal / Structural | |

| P21 | 40 | F | Italian | 1 y | - | Divorced | yes | ND | Relationship | |

| P22 | 59 | F | Ecuadorian | 15 d | 14 y | Divorced | yes | ND | Structural | |

| P23 | 63 | F | Serbian | 2 m | 8 y | Widower | yes | ND | Structural | |

| P24 | 62 | M | Italian | 5 y | - | Divorced | yes | Polytechnic school | Personal | |

| P25 | 65 | M | Italian | 4 y | - | Divorced | yes | ND | Relationship / Structural | |

| P26 | 57 | M | Italian | 3 y | - | Separated | yes | Primary school | Relationship / Structural / Personal | |

| P27 | 49 | M | Romanian | 2 y | 8 y | Divorced | yes | High school | Personal / Structural | |

| P28 | 34 | M | Italian | 7 m | - | Psychiatric hospital | Bachelor | no | Primary school | Personal |

| P29 | 47 | F | Italian | 8 y | - | Separated | ND | Middle school | Relationship | |

| P30 | 61 | M | Italian | 30 y | - | Jail | Separated | yes | Primary school | Relationship |

| P31 | 57 | M | Italian | 7 y | - | Jail | Divorced | no | Middle school | Structural |

| P32 | 55 | M | Italian | 2 y | - | Jail | Engaged | ND | Primary school | Relationship |

| P33 | 55 | M | Italian | 11 m | - | Jail | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Institutional |

| P34 | 32 | M | Moroccan | 2 y | 5 y | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Relationship | |

| P35 | 36 | M | Italian | 10 y | - | Engaged | yes | Middle school | Relationship | |

| P36 | 41 | M | Italian | 3 y | - | Bachelor | ND | High school | Relationship | |

| P37 | 50 | M | Algerian | 4 y | 22 y | Bachelor | no | ND | Structural | |

| P38 | 62 | M | Argentine | 4 y | 42 y | Bachelor | ND | ND | Personal | |

| P39 | 55 | M | Italian | 6 y | - | Separated | ND | High school | Relationship | |

| P40 | 52 | M | Italian | 8 y | - | Engaged | yes | ND | Structural | |

| P41 | 19 | M | Gambian | 1.5 ys | 1.5 y | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Structural | |

| P42 | 50 | M | Tunisian | 1 m | 16 y | Married | yes | ND | Structural | |

| P43 | 50 | M | Italian | 3 y | - | Bachelor | ND | Middle school | Structural | |

| P44 | 43 | M | Italian | 30 y | - | Bachelor | no | Middle school | Relationship | |

| P45 | 57 | M | Italian | 3 m | - | Jail | Divorced | yes | Primary school | Institutional |

| P46 | 46 | M | Italian | 7 m | - | Married | yes | Primary school (interrupte) | Relationship / Structural | |

| P47 | 46 | M | Tunisian | 2 m | 24 y | Separated | yes | Primary school (interrupte) | Structural | |

| P48 | 51 | M | Italian | 6 y | - | Separated | ND | ND | Relationship | |

| P49 | 43 | M | Italian | 5 m | - | Bachelor | ND | Middle school | Relationship / Structural | |

| P50 | 59 | M | Italian | 9 y | - | Separated | ND | High school | Relationship | |

| P51 | 31 | M | Albanian | 1 y | ND | Bachelor | ND | ND | Structural | |

| P52 | 55 | M | Italian | 25 y | - | Jail | Bachelor | ND | High school | Relationship / Institutional |

| P53 | 27 | M | Afghan | 3 y | 1.5 y | Bachelor | ND | High school | Structural | |

| P54 | 58 | M | Italian | 8 y | - | Alcohol Rehab Center | Divorced | yes | High school | Personal / Relationship |

| P55 | 49 | F | Moroccan | 1 y | 9 y | Divorced | no | High school | Personal / Structural |

Methodology

Since the narrative approach in topics related to homelessness has become prevalent, we utilized the thematic analysis, which is a specific approach to qualitative research developed from the Grounded Theory Methodology (GTM).27 Our research intersects such a methodology with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). The first one is a systematic inductive methodology involving the qualitative data in terms of their principal concepts or themes. The second one is a way of thinking about and conceptualizing indicators of significant phenomena, which may be cognized through a process of interpretative and hermeneutic work.28 Therefore, both GTM and IPA look at the active role of persons, who may offer profound and rich data, to understand psychological and social problems.

The analysis of the textual data was developed on the basis of both prior categories and categories which only became clear as analysis proceeded. The former were the basic pre-figured themes (religiosity, drug addiction/alcoholism, suicide ideation) from which the latter emerged as unexpected topics (biographical narrations, meaning of life and death). The process was divided into six main phases: preparatory organization; generation of categories or themes; coding data; testing emerging understanding; searching for alternative explanations; writing up the report. Moreover, before the last phase, the analysis of the textual data followed the strategies of the thematic-networks, which are the skeleton summarizing the main themes developed in the narrations. Thematic analysis was performed with Atlas.ti, which is a software that allows to identify the networks. The analysis results in flow charts, describing logical relationships between categories identified by researchers. The topic areas then form the basis for the research, within which extracts may be used to illustrate the final discussion.

Interview and data collection

The interviews consisted of a series of questions that were semi-directed, open-ended, and as in-depth as possible. Data were collected through narrations, and discussion was encouraged, so that participants could think of their biographies, main experiences, values, believes, meaning of life and death. Indeed, the dialogue was disposed to facilitate the personal reconstruction of the tellers’ story, and their efforts to shape places, times, and linkages between actions under different situations.

Each interview involved participants in meetings during lunch time. All 55 participants completed the interview. The topics were the following: 1. the personal biography: values, meaning of life, relationships, work and important events of past and present; 2. the street life: details on the current situation, emotions, prospects and future hopes; 3. deviance: abuse of alcohol or drugs, gambling, involvement in thefts and motivations; 4. Religiosity and meaning of death; 5. Suicidal ideation.

Each interview lasted for approximately two hours, was transcribed and checked for accuracy immediately after the dialogues.

The texts were coded, and variables were marked on the basis of age, gender, and occupation. Quotes that were forceful, persuasive, and convincing were highlighted and marked off for referencing.

Findings

Biographies and their main themes

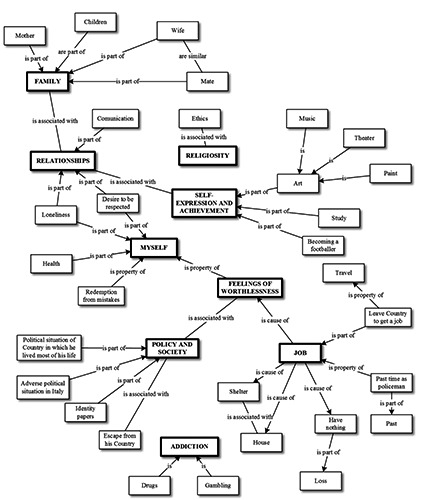

From the narratives of biographies important MTs emerged, assuming the role of pivots for the meaning of life and death. As shown in the Figure 1, the most important MTs are the following: myself and self-expression, feelings of worthlessness, family, relationships, policy and society, job, religiosity, and addiction.

Figure 1.

Main themes.

More specifically, Myself is composed by the desire to be respected, loneliness, worries for health. It is particular significant the need of redemption from mistakes: Now I do impossible things [ed. in order to redeem the past]. I always go running because I hurry, I do not like the comfortable life. And I would do many things together. It’s not in my nature, my nature would be doing a few things [P38: 29]; or high self-esteem: I was considered foreman because I had the capacity to be [P43: 17]; Now I use toothpicks, those for the skewers, to construct buildings. [...] And I never studied, right, I get these fantasies and I’m able to realize them [P49: 29].

Self-expression and achievement further develops the area of self-esteem and is constituted by artistic passions, which are as reasons for living as favorite dreams: I always think of the dreams that I have to accomplish [P53: 32]; I’ve always been a musician, always, always. I told my parents that when I die they have to play the Beethoven’s funeral march! Poooom Po po pooom! [P8: 16]. Feeling of worthlessness is a property of Myself and is caused by the Job. Participants talk about the difficulties related to research for and the bankruptcy of a job. They also willingly focus the conversation on their past activities and on causes of their failure: I look for work. I have no problem with 5 hours, 10 hours or more. Personally I do nothing. Just work. Just get a paycheck [P4: 25]; I would like just a job, and that’s it [P47: 16].

However, despite their present existential difficulties, our participants do not consider themselves responsible of their defeat. Indeed, Policy and society are the other side of the Feeling of worthlessness which explain the real cause of homelessness. The adverse political situations in Italy and in the country of origin running in parallel to the worries in the management of permissions and bureaucratic instances are the background of the downfall. I worked regularly in India, but now I am here because I had to get away from the social situation of my country. The real culprits of my condition are the Indian political leaders [P18: 29]; Now we go into the future. What kind of future do we have? What hope do we have? Politicians say that everything is OK. But where? How fantastic island? We still suffer from labor shortage, when these jokes ... Dear gentlemen, the chairs where you sit burn for certain reasons. The chair is hot right? [P43: 11]; I decided to leave my land, which for me is like my mother, who made me grow. When I left, I was twenty and I had lots of memories. I decided to do it because it was the only way to protect my life and my freedom [P53: 10].

Relationships is another important MT, linked to Self Expression and Achievement, and to Myself. In this area, some needs emerged for importance: suffering from loneliness and desiring to be respected: He isolated me from everyone. I could not do anything, he withdrew me everything, my phone and everything else. I lived four months on the street. But I was lucky because I met people who helped me: three Moroccans ... I was scared, but they helped and defended me several times. [P21: 34]. The MT inherent to Family is strictly linked to the themes of Relationships, including the narrations regarding both the parents, consorts, children and mates. I’m young, I have to think ahead, I have to start family with home, wife, children. Seeing your children is the best thing in life [P10: 17]; Then, unfortunately, when there is a family breakup, it is useless, as you say, trying to ... how do you say, when you smash a glass and you want to paste? There you have always broken shards, it is no longer as it was. […] As they say, when you bother, you no longer have the right to speak. What the fuck have I done? How many sacrifices! All this leads you to make choices. Unfortunately, I made this choice: I will not do shit. I do not feel anymore. I found myself in the street [P35: 14]; The most difficult times are when maybe you are alone and think about what you were and your life, your son, your ex-wife [P54: 9]. It is noteworthy that the only two MTs not related to the others are Addiction and Religiosity. The first one is characterized by the description of the form of dependency and their relationships with the life on street. To one who is starting to live on the street? I would say that if you made family quarrel, if your parents do not want you because you’re drugging, go to the health service, cared for, but do not end up on the street! Do not stand in the street! The road is the worst thing you can chose. Remain in the family! [P9: 25]; I’ve lost 900,000 euro in four years. […] When you play at the casino, the cards, the latter shall lose my life. [...] In one day I lost thousands of euro. In 2013 I lost € 37,000. All these houses of the station, the neighborhood, were all mine. I had flat there, there and there [P16: 14].

However, the moral questions are linked to the reflection on Religion, which is particular important in the ethical evaluations of existential choices. A catholic and alcoholic Italian, who have been living on the street for six year, considers his condition as existentially tragic as morally right: I sell the paintings now twenty, thirty euro and I’m so happy. I mean, it’s so difficult but [...] If God gives you a gift you have to use. Now I’m doing it. If you do one thing you have to do, it’s OK [P39: 4]. Similarly, a drug addicted Senegalese can bear his condition thank to a complex and terrifying mythology: The first [ed. greatest satisfaction in this world] is faith. Do you know that here there were two worlds? [...] All their sizes are different in everything from the matter at all. It was repeated twice. The whole cycle of the world that was created and then it ended. [...] I am dedicated to religion. I spent all the belongings of mine to know the truth. Because I really wanted to know what I was going through, because it has been scaring me [P6: 23]. A Catholic Italian with suicidal ideation finds in a personal theodicy the most important pivot on which the self-esteem can be maintained: It’s the people who disbelieve. People think they know that [ed. God] exists. But they do not know what character [ed. He] turns. They think they go to church, take communion and to be in peace with God. No! You’re not in peace with God, you had to be in peace with God in the confessional, through the priest that should give you the blessing. But you are not in peace with God, because He is seeing everything you do. With the usual chatter of God ... God say you should not eat God, you have to carry alone in the heart, not in the mouth [P52: 20].

Suicide between addiction and religion: the role of MTs

Our findings confirm the general rate descripted by the literature: in fact, 20 participants (27.5%) have been thinking or have thought of suicide, while 12 (22%) were addicted or alcoholics. These subjects are almost all Catholics or Muslim, believing that death is a passage toward God or a transformation into another dimension. The representation of death as annihilation is assumed by only 4 participants (7.3%), among whom one is drug addicted, while one meditated to commit suicide in the past. These data point out that neither religiosity nor meaning of death as a passage toward God can be considered as protective factors with respect to addiction/alcoholism or suicide ideation.

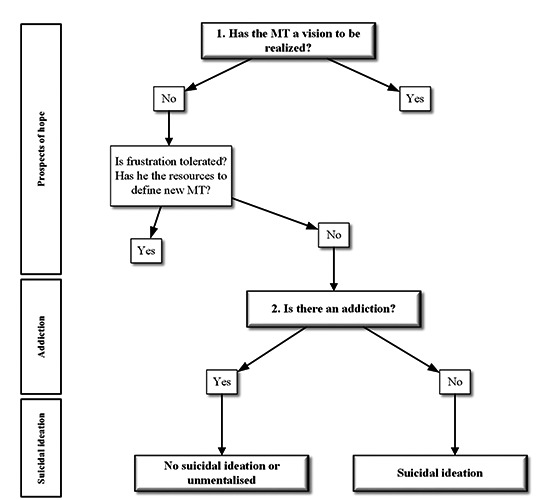

The thematic analysis helped us to reconstruct the relationships among these aspects. In fact, the most important factor determining the suicidal ideation has been the frustration of the MTs characterizing the reasons for living. The hopelessness inherent to the realization of the main theme of life is the fundamental cause of addiction and suicide ideation. In fact, through the in-depth analysis of the texts we could detect the relationships between the frustration of what is believed to be the MT qualified as a reason for living and addiction or suicidal thoughts. With respect to the 53 cases examined (P51 and P52 are excluded because information on addiction [P51] and suicidal ideation [P52] was not provided), we found that until the MTs retain their value for meaning life, participants reject suicide and do not abuse of alcohol or drugs. However, participants who abuse of alcohol and drugs reject suicide. In the flow chart of the Figure 2 we describe the structure of the thematic analysis that shows the relationships between MTs, addiction and suicide (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Model prospects of hope, addiction and suicide.

Table 2.

Drug addiction and suicidal ideation compared with main themes, religion and representation of death.

| Suicidal ideation | Addictions | Recurring feelings and leanings | Main Themes | Religion | Death representation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Yes | - | Rage, denying of reality | Children, Job | Muslim | Transition |

| P2 | Yes, but not now | - | Sociability, hope | Job, Leave Country to get a job | Muslim | Transition |

| P3 | Yes | - | Disillusion | Travel | Muslim | Transition |

| P4 | No | - | Sociability, honesty | Relationships, Comunication, Job | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P5 | No | Alcohol, drug | Unsociability, rage, pessimism, vindictive thoughts, hope |

Children, Desire to be respected | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P6 | No | Drug | Sociability, generosity, composure | Spirituality, Music | Animist | Transformation |

| P7 | Yes | - | Fear, loneliness | Family | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P8 | No | Alcohol | Sociability | Wife, Children, Music | Orthodox Christian | Transition |

| P9 | Yes | Drug | Sociability, rage, quick temper | Relationships, Drugs | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P10 | No | - | Hope | House, Family | Muslim | Transition |

| P11 | No | - | Unsociability, loneliness | Redemption from mistakes | Atheist | Annihilation |

| P12 | No | Alcohol | Unsociability, rage | Job | Muslim | Transition |

| P13 | No | Alcohol | Patience, hope | Spirituality | Muslim | Transition |

| P14 | No | Alcohol | Rage | Children | Agnostic | Transformation |

| P15 | No | - | Composure | Policy and society | Muslim | Transition |

| P16 | No | Alcohol, GAP | Unsociability, GAP obession | Gambling | Atheist | Annihilation |

| P17 | No | - | Mistrust, rage, suspiciousness | Job, Family | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P18 | No | - | Trust, gratitude, fear | Policy and society, Escape from his Country | Muslim | Transition |

| P19 | No | - | Rage, racism perception, desire to come back home | Family | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P20 | Yes, but not now | - | Loneliness, abandoned | Children, Relationships | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P21 | No | - | Incredulity, dubt for tomorrow | Ethics; Relationships | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P22 | No | - | Desire for independece, willpower | Children | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P23 | No | - | Peaceful attitude, faith | Children, Spirituality | Orthodox Christian | Transition |

| P24 | Yes, but not now | - | Loss of interest, hope, disillusion, empty days | Job, Relationships | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P25 | Yes | - | Suffering in thinking about past, feel unlucky | Family | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P26 | Yes | - | Rage, bitterness, humiliation, feeling of being locked | Wife | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P27 | Yes, but not now | - | Impulsiveness, good self-esteem | Children | Eclecticism of religions | Transition |

| P28 | Yes | - | Loneliness, bad luck, empty days | Mother, Loneliness, Health | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P29 | Yes | - | Resentment, need companionship, desire to help others | Relationships | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P30 | No | - | Impulsiveness, optimistic, self-perception: strong | Himself | Atheist | Annihilation |

| P31 | No | - | Pessimism, feeling humiliated, discouragement | Loneliness, Loss | Agnostic | Transformation |

| P32 | No | - | Bitterness, perceived discrimation, desire to help others | Loneliness, Mate | Agnostic | Transformation |

| P33 | No | - | Ability to see the positive aspects, happiness, good self-esteem | Spirituality | Protestant Christian | Transition |

| P34 | No | Alcohol | Feeling understood, empty days | Job, House | Muslim | Transition |

| P35 | Yes | - | Loneliness, bitterness, mentally locked, apathy | Family, Loneliness | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P36 | No | - | Ability to see positive aspects, empty days | Relationships | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P37 | No | - | Discrimination perceived | Shelter | Muslim | Transition |

| P38 | Yes, but not now | - | Good self-esteem, intolerance for injustice | Himself, Theater, Policy and society, Travel | Atheist | Annihilation |

| P39 | No | Alcohol | Sociability, good self-perception, hope | Relationships, Family, Paint | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P40 | Yes | - | Regret, unable to accept the current condition | Family, Job | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P41 | No | - | Hope, live for today | Becoming a footballer | Muslim | Transition |

| P42 | No | - | Indifference perceived | Family, Job | Muslim | Transition |

| P43 | No | - | Bitterness, good self-esteem | Himself, Policy and society | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P44 | No | - | Disillusionment, empty days | Job | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P45 | Yes | - | Disbelief, pride, trampled dignity | Family, Relationships, Loneliness | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P46 | Yes | - | Bitterness, frustration, rage, feeling useless | Feelings of worthlessness, Job, Children, Have nothing | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P47 | Yes | - | Bitterness, nostalgia, rage, empty days | Job, Identity papers, Loneliness | Muslim | Transition |

| P48 | Yes | - | Feeling victim, feeling betrayed | Past, Relationships, Policy and society | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P49 | Yes, but only at the beginning | - | Hope, empty days, desire to help others | Family, Himself | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P50 | No | - | Bitterness, nostalgia, rae, empty days | Policy and society, Relationships | Agnostic | Transformation |

| P51 | No | ND | Rage, intolerance for the present status | Job | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P52 | ND | - | Sadness, empty days, faith | Spirituality | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P53 | No | - | Nostalgia, patriotism, respect | Policy and society, Study | Naturalism | Transformation |

| P54 | No | - | Disillusionment, regret, desire to help others | Family, Past, Music | Catholic Christian | Transition |

| P55 | No | - | Hope, courage, desire to help others | Spirituality | Muslim | Transition |

The first step identifies those who do not want to commit suicide and not resort to substances because they feel that their MTs’ reasons for living are still achievable. An Indian young man, who has been living in the street for only three months, says: Yes, it could be understandable if someone commits suicide or takes drugs, but you must not surrender to the temptation to succumb … At the moment, I haven’t yet found anything, but I don’t get down. I do not give up on life… Among homeless people I have so many friends and I love chatting with them [P4: 22].

The second step presents those who do not solve their problem with addiction or suicide because, despite they lost their MTs’ reasons for living, they are convicted that new solutions may spring in the future. For example, a Maroccan lawyer, while feeling betrayed by politics in which he deeply believed (his MT), maintains a serene and open attitude towards the future: We should not despair, lose hope. Life is good, although it is not easy. I now am old, I have high hopes for the future, I just hope that things can go a bit ‘better. But if it does not, patience! I shall find other solutions, as I learned to do until now. At the beginning it was very hard, but now I have learned to live well without nothing and I shall do so in the future [P15: 10].

The third step is inherent to participants who do not perceive the possibility to achieve their MTs’ reasons for living and cannot find new solutions, suffering from a deep frustration. They can no longer tolerate their condition, and so drug and alcohol become a possible solution. For example, a Moroccan alcoholic, whose main MT is entirely developed in loving his, who unfortunately are not disposable to meet him because of the divorce. His state is highly painful, however he is able to manage it finding the strength to love living No, no, no, I never thought to commit suicide. [...] Of course there are pressures, but with the optimism you have to fight them for a living. Life is beautiful, and when is too difficult … (ed. I drink)! [P14: 25]. Such perspective highlights how addiction is a compensation strategy for handling the pain, frustration and anguish.

The fourth step shows the path of those who do not consider drugs and alcohol as support and so believe that suicide could be a possible solution. An Italian who has been living in the street for 8 years has been thinking that suicide could be a good answer because: It is difficult to find work at this age, even for you that are so young it is not easy to find a job, so imagine how it is difficult for me! What can I do? [P40: 4]. Similarly, a forty-year-old Maroccan has been thinking to commit suicide because his position of unemployment has removed the hope of seeing his children: It’s really unbearable … Any kind of work was going well. I was forced to work illegally in order to survive for so long. Now there is no work absolutely. I still look for it, but everything is pointless [P1: 21]. Suicide has been described a possible solution also in the narration of a Catholic Italian fifty-year-old woman, who has been living in the street for one year I have to get back among everyday people. I fear the night when it is dark and I’ll be alone. [...] I need company. I hope that when I go out, my children, two or three times a week will come to see me. One thing that I have to face suicide [P20: 28]. Hopelessness caused by the loss of significant activity produces the same effect in the biography of an Argentine atheist, living in the street for 4 years: I was in a theater group in Argentina. It is a kind of therapy. Doing theater, you learn how to make the clay, and it is very therapeutic, both the head and the body. In fact, I think I got sick because I miss these things [P38: 13].

Conclusions

This qualitative research explored the relationship between religiosity, suicide thoughts and drug abuse among homeless people in order to analyze the meaning of life and death through the biographical narrations and their main themes, focusing on the relationships between religiosity, addiction and suicide ideation. Following the narrations of participants, our findings confirm that alcoholism and abuse of drugs help them to compensate the crisis deriving from difficulties caused by living in the street and that substance abuse, although harmful to health, is a strategy to deal with daily suffering.5,6 Literature shows how religiosity reinforces health behavior, preventing from suicide and addiction. Since drug addiction, self-harm and suicide are strongly condemned by all religions, we wanted to analyze whether being believers could be a protective factor or not in homelessness condition. Unfortunately, our results are discordant with the perspective that consider religiosity as a resilience factor because the analysis of the narrations of our participants show that neither religion nor the meaning of death as a passage toward God can prevent addiction and the desire of committing suicide. This result confirms what already described by literature revealing that suicidal ideation is significantly present in homeless people suffering from hopelessness, linked to the lack of social support, and not by those who use alcohol or drugs.12 However, our thematic analysis also illustrates the dynamic which characterize the relationships among some main themes which may maintain hope but also may cause hopelessness. The descriptions of the MTs derived from the answers inherent to the meaning of life and death, which finally seem to be really similar to the perspective introduced in suicidology by Marsha Linehan. The researcher revolutionized the previous psychological theories, which have had traditionally emphasized the negative factors influencing suicidal behavior, by the description of a variety of negative causes. From a diametrically opposite point of view, Linehan and collaborators conducted studies that specifically focused on reasons why someone would not want to commit suicide.25 They are really similar to the main themes we could recognize in the biographies of our participants, among which resilience, religion, family, job and aims to reach. Linehan’s research involved diverse groups and categories of people who were asked to reflect upon a time in their lives when they had been most seriously suicidal and then to list the reasons why they did not kill themselves. Similarly, we asked our participants some questions on the sense of life and death, aware of the fact that such problems constitute the fundamental existential difficulty, which characterizes the Western contemporary culture, as efficaciously indicated by Albert Camus in The Myth of Sisyfus. The philosopher and dramatist stated that living is never easy and that common people continue making the gestures commanded by existence for many reasons, the first of which is habit. In his opinion, dying voluntarily implies that person has recognized the ridiculous character of any routine, the absence of any profound reason for living, and the uselessness of suffering. In such a perspective, there is not any absolute meaning of life and all customs are inevitably destined to show the nonsense of existence. Camus was atheist and believers find his perspective substantially nihilist. As indicated by TMT,29 the negation of death through faith in literal or symbolic immortality produces values that manage the terror of death and buffer anguish, by providing the sense that one is part of something greater that will ultimately outlive the individual or by making one’s symbolic identity superior to biological nature. However, our findings show that our homeless people, who are almost all believers, do not find neither in religion nor in immortality a sufficient reason for avoiding suicide.

An article by David Jobes and Rachel Mann30 addressed the objective to illustrate the opposition between the reasons for living versus the reasons for dying. The authors considered the results of the research of Marsha Linehan on the protective factors which help people to avoid suicide, underlying that the same variety of reasons for living, which are the most common habits indicated by Camus or values considered by TMT, ultimately correspond to the reasons for dying. When the main themes of the biographies, which are the pivotal reasons for living, fail, suicide result as the last solution.

The limitations of this study consist on the intercultural difficulty derived from the different perspective of participants. The analysis of the main themes could have be better developed if a list of different possible habits had been available, providing useful inputs in order to facilitate narratives, linked to biographical aspects.

Funding Statement

Funding: none.

References

- 1.Busch-Geertsema V, Edgar W, O’Sullivan E, Pleace N. Homelessness and homeless policies in Europe: lessons from research. Brussels: Feantsa; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busch-Geertsema V, Benjaminsen L, Hrast MF, Pleace N. Extent and profile of homelessness in European member states. Brussels: European Observatory on Homelessness; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pleace N. Immigration and homelessness. O'Sullivan E. (ed). Homelessness research in Europe. Brussels: Feantsa; 2011. pp 143-163. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim MM, Ford JD, Howard DL, Bradford DW. Assessing trauma, substance abuse, and mental health in a sample of homeless men. Health Soc Work 2010;35:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer PJ, Breakey WR. The epidemiology of alcohol, drug and mental disorders among homeless persons. Am Psychol 1991;46:1115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kipke MD, Montgomery SB, Simon TR, Iverson EF. Substance abuse disorders among runaway and homeless youth. Subst Use Misuse 1997;32:969-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz TL. Substance misuse, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among a national sample of homeless. J Soc Serv Res 2010;37:1-18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pleace N, Quilgars D. Improving health and social integration through housing first: a review. Brussels: Feantsa; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prigerson HG, Desai RA, Liu-Mares W, Rosenheck RA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in homeless mentally ill persons: age-specific risks of substance abuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Procter NG, De Leo D, Newman L. Suicide and self-harm prevention for people in immigration detention. Med J Aust 2013;199:730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoder KA. Comparing suicide attempters, suicide ideators, and nonsuicidal homeless and runaway adolescents. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 1999;29:25-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamura T, Ito K, Morikawa S, Awata S. Suicidal behavior among homeless people in Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:573-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonas E, Fischer P. Terror management and religion: evidence that intrinsic religiousness mitigates worldview defense following mortality salience. J Pers Soc Psychol 2006;91:553-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronconi L, Testoni I, Zamperini A. Validation of the Italian version of the reasons for living inventory. TPM Appl Psychol 2009;16:151-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/spirituality and mortality: a systematic quantitative review. Psychother Psychosom 2009;78:81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Testoni I, Milo V, Ronconi L, et al. Courage and representations of death in patients who are waiting for a liver transplantation. Cogent Psychol 2017;4:1294333. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pescosolido BA. The social context of religious integration and society: pursuing the network explanation. Sociol Q 1990;31:337-57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne IR, Bergin AL, Bielema KA, Jenkins PH. Review of religion and mental health. Prev Hum Serv 1991;9:11-40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Testoni I, Ancona D, Ronconi L. The ontological representation of death. Omega 2015;71:60-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung AM, Hwang SW. Risk of death among homeless women: a cohort study and review of the literature. CMAJ 2004;170:1243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connell JJ. Premature mortality in homeless populations: a review of the literature. Nashville: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, et al. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction 2011;106:32-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roerecke M, Rehm J. Alcohol use disorders and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2013;108:1562-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Douglas AN., Jimenez S, Lin H, Frisman LK. Ethnic differences in the effects of spiritual well-being on longterm psychological and behavioral outcomes within a sample of homeless women. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2008;14:344-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Neilsen SL, Chiles JA. Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the reasons for living inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:276-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snow DA, Anderson L, Koegel P. Distorting tendencies in research on the homeless. Am Behav Sci 1994;37:461-75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbin JM, Strauss AM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. 3rd ed. New York: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gill MJ. The possibilities of phenomenology for organizational research. Organ Res Meth 2014;17:118-37. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. A terror management theory of social behavior: the psychological functions of self-esteem and cultural worldviews. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 1991;24:93-159. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jobes DA, Mann RE. Reasons for living and reasons for dying: examining the internal debate of suicide. Suicide Life -Threat Behav 1999;29:97-104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]