Abstract

Introduction

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) are widely available and come in a variety of forms, including disposable cigalikes and refillable tank systems. However, little is known about their placement at the point-of-sale. We explored the placement of various ENDS types among tobacco retailers.

Methods

Systematic assessments at the point-of-sale were completed by trained data collectors in 90 tobacco retailers, including grocery stores, convenience stores, and pharmacies in North Carolina, United States. Availability and placement of various ENDS types including cigalikes, e-hookahs, tank systems, and e-liquids was recorded.

Results

Almost all retailers (97.8%) sold cigalikes; 41.4% sold devices labeled as e-hookahs; 54.4% sold tank systems; and 56.2% sold e-liquids. Fewer than half of stores placed ENDS exclusively behind the counter; significant differences in ENDS placement were found by store type. Grocery stores carried cigalikes, tank systems, and e-liquids and placed them exclusively behind the counter. Pharmacies only sold cigalikes; most placed them exclusively behind the counter (91.7%) with cessation aids and other tobacco products. Convenience stores carried all ENDS types and placed them with other tobacco products (55.1%) and candy (17.4%). Only about one-third of convenience stores placed ENDS exclusively behind the counter.

Conclusions

This exploratory study shows ENDS availability and placement at the point-of-sale varies by retailer type. Pharmacies placed cigalikes with cessation aids behind the counter suggesting their ability to aid in smoking cessation. Most convenience stores placed ENDS in self-service locations, making them easily accessible to youth. Findings highlight the need for ENDS regulation at the point-of-sale.

Implications

Our study highlights the need for regulatory efforts aimed at ENDS placement at the point-of-sale. While pharmacies and grocery stores offered fewer ENDS types and typically placed them in clerk-assisted locations, all ENDS types were found at convenience stores, some of which were placed in youth-friendly locations. Regulatory efforts to control ENDS placement and limit youth exposure should be examined, such as requiring products be placed in clerk-assisted locations and banning ENDS placement next to candy.

Introduction

Sales of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) have increased significantly since becoming available in the United States.1 ENDS are available in many different forms including disposable and cartridge-based electronic cigarettes which mimic conventional cigarettes in appearance and flavor (“cigalikes”); tank systems which typically have a longer battery life and can be refilled with flavorful e-liquids; and manufacturer-labeled electronic hookahs (e-hookahs). E-hookahs are similar in size and technology to cigalikes, but are typically decorated with colorful designs and are most often purchased without nicotine in fruity flavors that are common in traditional waterpipe smoking. The various types of ENDS may appeal to different consumers as they vary in price, look, battery strength, and flavor options,2,3 as well as nicotine delivery,4 and user satisfaction.5

The broad tobacco control literature provides substantial evidence that the retail environment is used by tobacco companies to attract and maintain consumers through advertising, price promotions, and product placement.6–8 The point-of-sale environment includes several venues for tobacco marketing, including advertising through product placement on power walls, at self-service displays, and standalone displays. Power walls are typically behind the checkout counter and require a clerk to obtain the product for the customer, compared to self-service displays (typically on the counter) and standalone displays (typically in a store aisle) which allow customers to select products on their own and thereby increasing their availability to consumers.9 Within each of these venues, retailers are incentivized for using branded display units and placing items at eye level or in proximity to common items, such as candy and other everyday items, which may increase impulse purchases, normalize tobacco use, attract new users, and increase smoking uptake.10,11 In the United States, self-service displays are banned by federal law for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products;12 however, this regulation does not apply to ENDS or other tobacco products.13 To fill this gap, a few states and localities have passed legislation to prohibit self-service of noncigarette tobacco products, including ENDS.14,15

One study has assessed ENDS placement among tobacco retailers at the point-of-sale and found the vast majority of retailers (90.2%) sold cigalikes, 37.3% sold cartridges/refills, and 15.7% sold tank systems. Even though most stores placed them behind the checkout counter (88.2%), 10% of stores placed them at a child-friendly height (at or below 3½ feet).16 While this was the first study to assess placement of various ENDS types in the retail environment, it did not examine availability or placement at different store types such as convenience stores, grocery stores, and pharmacies, which may vary in how they market ENDS to consumers. For example, convenience stores, where almost half of U.S. teenagers report visiting at least one time a week,17 are more likely than other store types to have traditional tobacco products near candy8 and placement contracts with tobacco companies.7

The focus of this exploratory study is to: (1) assess the availability of ENDS sub-types among tobacco retailers including convenience stores, grocery stores and pharmacies; (2) describe their placement at the point-of-sale; and (3) assess adjacency to tobacco products, cessation aids, and candy.

Methods

Data for this study was collected as part of a larger study to examine availability of tobacco products among tobacco retailers in the Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia Metropolitan Statistical Area. The Metropolitan Statistical Area includes seven counties in North Carolina (NC) and three in South Carolina (SC) and has a population of approximately 2.4 million people.18 Only NC communities were included in the sample due to differences in tobacco licensing between NC and SC. There were no state or local laws addressing ENDS placement at the point-of-sale in the study communities.

Sampling Frame

Because NC does not have tobacco retail licensing, a list of potential tobacco retailers was created by adapting procedures that are used to identify retailers for SYNAR tobacco compliance checks in NC.19 We searched the state’s Alcohol Beverage Control website for businesses that were located in the Metropolitan Statistical Area and held a current off-premise alcohol license. Next, we compiled a supplemental list of potential retailers from online search queries of a tobacco industry website to determine additional tobacco retailers in the NC communities. These lists were merged, cleaned, and de-duplicated to produce a final list that resulted in 246 potential tobacco retailers. A random sample of 100 stores was selected for audit.

Procedures

Teams of two trained research staff worked together to complete the audit at each store using tablets for data entry. Audits were conducted during a 3-week period in the Spring of 2014. The unannounced audits took approximately 10–15 minutes per retail outlet to complete. Retailer consent was not required; however, data collection was terminated if requested by the retailer.

Measures

Auditors recorded the outlet type (convenience store with or without gas; grocery store; pharmacy; other) and assessed multiple tobacco products, including four ENDS types: (1) disposable and cartridge-based e-cigarettes (cigalikes); (2) e-hookahs, as labeled by the manufacturer; (3) tank systems; and (4) e-liquids. Information about placement was captured in two ways. First, auditors recorded ENDS placement in relationship to the check-out counter (on top of the counter; in front of the counter; and/or behind the counter). Second, ENDS placement next to the following products was assessed: combustible cigarettes (Yes/No), smokeless tobacco (ie, chew, dip, and snus) (Yes/No); tobacco cessation products (Yes/No); candy (Yes/No); standalone display (Yes/No). ENDS could be placed next to multiple products in the same store. Descriptive and Pearson’s chi-square test analysis were performed. For small cell sizes, a Fisher’s exact test was conducted. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3.

Results

Of the 100 stores randomly selected for audit, 6 stores refused data collection; 1 store could not be located with the given address; and data was only partially saved in 3 stores due to equipment error. Therefore, full assessments were completed in 90 tobacco-selling retailers, including 71 convenience stores, 7 grocery stores, and 12 pharmacies.

ENDS Availability

Overall, ENDS were widely available, with 97.8% of retailers selling ENDS. All grocery stores and pharmacies and 97.2% of convenience stores sold at least one ENDS type. Almost all stores (97.8%) sold cigalikes; 41.4% sold e-hookahs; 54.4% sold tank systems; and 56.2% sold e-liquids. Convenience stores sold all ENDS types, grocery stores sold cigalikes, tank systems, and e-liquids; and pharmacies only sold cigalikes.

Placement at Point-of-Sale

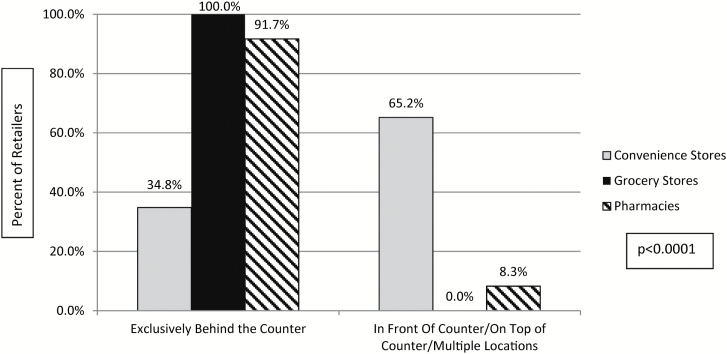

Among retailers that sold ENDS (N = 88), 47.7% placed ENDS exclusively behind the counter; 52.3% placed them in front of the counter, on top of the counter, or in multiple locations. Their placement varied significantly by store type (p < .01). Approximately one-third (34.8%) of convenience stores placed ENDS exclusively behind the counter, compared to 91.7% of pharmacies and 100% of grocery stores (Figure 1). We further examined placement among convenience stores since the majority (65.2%) placed ENDS in self-service locations. About half of convenience stores placed cigalikes and e-hookahs exclusively behind the counter (49.3%; 51.4%). Tank systems and e-liquids were placed exclusively behind the counter in about one-third of convenience stores (37.2%; 36.4%).

Figure 1.

ENDS placement at the counter, among stores that sold ENDS, (N = 88).

Adjacency to Other Products

Among all retailers, 63.6% placed ENDS with traditional tobacco products, 14.8% placed them with cessation aids, 29.6% placed them in standalone displays, and 13.6% placed them with candy (Table 1). Among convenience stores, 55.1% placed them with traditional tobacco products, 37.7% placed them in standalone displays, 17.4% next to candy, and 1.5% placed them with cessation aids. All grocery stores placed ENDS exclusively with traditional tobacco. All pharmacies placed ENDS with cessation aids and 91.7% also placed them with traditional tobacco products. Grocery stores and pharmacies were more likely to place ENDS with traditional tobacco products compared to convenience stores (p < .01); convenience stores were more likely to place ENDS in standalone displays (p < .01) and were the only store type to place them with candy; and pharmacies were more likely to place ENDS with cessation aids (p < .01).

Table 1.

ENDS Placement with Other Products, Among Stores that Sold ENDS (N = 88)

| Convenience store with or without gas N (%) | Grocery stores N (%) | Pharmacy N (%) | All stores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENDS Placement | N = 69 | N = 7 | N = 12 | N = 88 | *p value |

| Standalone display | 26 (37.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (29.6) | .003 |

| With cessation aids | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (100.0) | 13 (14.8) | .006 |

| With candy | 12 (17.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (13.6) | .21 |

| With other tobacco products | 38 (55.1) | 7 (100.0) | 11 (91.7) | 56 (63.6) | .004 |

*p < .05.

Discussion

Our study expands the limited literature on the availability of ENDS subtypes and their placement at the point-of-sale among traditional tobacco retailers in the United States. Our finding that ENDS are widely available, with 97.8% of stores selling at least one type of ENDS, is consistent with the existing research.16,20 We examined the types of products sold by store type and found convenience stores were more likely to carry all ENDS products. In contrast, pharmacies only carried cigalikes, perhaps appealing to smokers who are trying to quit.21 E-hookahs, one of the more novel subtypes, were only sold in convenience stores. This may be because convenience stores offer novel products as a way to add new customers and new reasons to visit the store.22 In addition, convenience stores are visited by approximately 47.5% of U.S. adolescents and young adults each week,17 a population that perceives sub-type differences between e-hookahs and cigalikes. For example, in a study among adolescents and young adults, e-hookah users were perceived as young and trendy while cigalike users were perceived as old and addicted to nicotine.2 Thus, convenience stores may be offering products that appeal to the adolescent and young adult population.

Placement of tobacco products in locations that target youth, such as near candy and at a height of below or at 3½ feet, increases youth exposure and may encourage experimentation and use.10,11 We found that convenience stores were the only store type to place ENDS with candy, and interestingly all ENDS types were placed there. Although the percentage of stores that placed ENDS with candy was only about 10%, a finding consistent with the existing literature,10 these findings highlight that regulations aimed at eliminating this type of targeted marketing are still needed to reduce youth exposure.

Similarly, self-service locations, such as standalone displays and countertop displays, increase product access, especially to youth. One strategy to reduce youth access is to require that tobacco products be exclusively placed behind the counter necessitating a face-to-face interaction to purchase them, as is the case for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco.6–8,11 Although several states and localities have passed ordinances banning self-service,14 there were no such ordinances in place in NC at the time of data collection. While such a policy would likely apply to all retailers, it may only be needed for specific store types, as all grocery stores and most pharmacies (91.7%) in our study placed ENDS exclusively behind the counter, while almost two-thirds of convenience stores did not. Convenience stores are likely placing the products in more prominent locations to increase sales and profitability23 and are unlikely to place them exclusively behind the counter without specific regulations.

Our study also examined ENDS adjacency to other products to more fully understand the retail environment in which consumers are exposed to ENDS. Although pharmacies placed ENDS next to tobacco products, they were more likely to place ENDS with cessation aids compared to grocery stores and convenience stores, suggesting ENDS are being subtly promoted as a cessation aid. While most agree that ENDS are less harmful than combustible cigarettes, ENDS are not approved by the FDA as a smoking cessation product24 and their placement next to cessation aids may suggest to consumers that ENDS are effective smoking cessation tools. More research is needed with larger sample sizes to determine if this placement is common among pharmacies.

Since U.S. federal law does not restrict ENDS placement at the point-of-sale, individual states currently have this regulatory responsibility. Globally, countries are taking varied approaches in regulating ENDS ranging from complete bans, to regulation as tobacco, medicinal, and/or consumer products, to no product regulation.25 Currently, 58 countries regulate advertising, promotion or sponsorship of ENDS, some of which include the point-of-sale.26 Policies need to be reviewed to determine if ENDS fit into the existing laws or if new or amended laws need to be considered to address ENDS placement at the point-of-sale.

Limitations

Our findings have limited generalizability and our sample may not represent the entire universe of tobacco retailers in the Metropolitan Statistical Area. In addition, our sample included more convenience stores compared to the other store types; therefore inferences about differences between retailers should be made with caution. Nevertheless, this study offers early observations of variation in retail practices around ENDS placement at the point-of-sale and highlights the need for future surveillance.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant number 3RO1CA141643-05S1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Euromonitor International. Vapour Products in the US. 2016. http://www.euromonitor.com/vapour-products-in-the-us/report. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, Teal R, Moracco KE, Sutfin EL. E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: adolescent and young adult perceptions of electronic nicotine delivery systems. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):2006–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yingst JM, Veldheer S, Hrabovsky S, Nichols TT, Wilson SJ, Foulds J. Factors associated with electronic cigarette users’ device preferences and transition from first generation to advanced generation devices. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1242–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, Stefopoulos C, Romagna G, Voudris V. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dawkins L, Kimber C, Puwanesarasa Y, Soar K. First- versus second-generation electronic cigarettes: predictors of choice and effects on urge to smoke and withdrawal symptoms. Addiction. 2015;110(4):669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lavack AM, Toth G. Tobacco point-of-purchase promotion: examining tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen JE, Planinac LC, Griffin K et al. Tobacco promotions at point-of-sale: the last hurrah. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(3):166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Schleicher NC, Clark PI. Retailer participation in cigarette company incentive programs is related to increased levels of cigarette advertising and cheaper cigarette prices in stores. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teall AM, Graham MC. Youth access to tobacco in two communities. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(2):175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackintosh AM, Moodie C, Hastings G. The association between point-of-sale displays and youth smoking susceptibility. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(5):616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pollay RW. More than meets the eye: on the importance of retail cigarette merchandising. Tob Control. 2007;16(4):270–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. H.R. 1256 — 111th Congress: Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. 2009. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr1256. Accessed September 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Food and Drug Administration. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products; Final Rule. May 10, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/EconomicAnalyses/ucm394922.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Report: Policy Activity 2012–2014. St. Louis, MO: Center for Public Health Systems Science at the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis and the National Cancer Institute, State and Community Tobacco Control Research Initiative; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. 2016. Laws/Regulations Restricting Sale of Electronic Smoking Devices and Alternative Nicotine Products to Minors http://publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/ us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review. Legal Resource Center for Maryland Public Health Law and Policy. https://www. law.umaryland.edu/programs/publichealth/documents/ LRC_ESD_Legislation.pdf.

- 16. Brame LS, Mowls DS, Damphousse KE, Beebe LA. Electronic nicotine delivery system landscape in licensed tobacco retailers: results of a county-level survey in Oklahoma. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanders-Jackson A, Parikh NM, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Convenience store visits by US adolescents: rationale for healthier retail environments. Health Place. 2015;34:63–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Data USA. Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC Metro Area. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/charlotte-gastonia-rock-hill-nc-sc-metro-area/#intro. Accessed April 29, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wagoner KG, Song EY, Egan KL et al. E-cigarette availability and promotion among retail outlets near college campuses in two southeastern states. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(8):1150–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giovenco DP, Casseus M, Duncan DT, Coups EJ, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD. Association between electronic cigarette marketing near schools and e-cigarette use among youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(6):627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rose SW, Barker DC, D’Angelo H, Khan T, Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, Ribisl KM. The availability of electronic cigarettes in U.S. retail outlets, 2012: results of two national studies. Tob Control. 2014;23:iii10–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Nielsen Company. Continuous Innovation: The Key to Retail Success. January 7, 2014. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/ insights/reports/2014/continuous-innovation-the-key-to-retail-success.html. Accessed March 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ericksen AE. How to Add Space for E-cigarettes. Convenience Store Decisions. October 5, 2015. www.cstoredecisions.com. Accessed September 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA 101: Smoking Cessation Products. November 9, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm198176.htm. Accessed April 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, DECISION. Fifth Plenary Meeting, 18 October 2014. apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6(9)-en.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Country Laws Regulating E-cigarettes: A Policy Scan. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; http://globaltobaccocontrol.org/e-cigarette/country-laws-regulating-e-cigarettes. Accessed June 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]