Abstract

In a Dutch consanguineous family with recessively inherited nonsyndromic hearing impairment (HI), homozygosity mapping combined with whole-exome sequencing revealed a MPZL2 homozygous truncating variant, c.72del (p.Ile24Metfs∗22). By screening a cohort of phenotype-matched subjects and a cohort of HI subjects in whom WES had been performed previously, we identified two additional families with biallelic truncating variants of MPZL2. Affected individuals demonstrated symmetric, progressive, mild to moderate sensorineural HI. Onset of HI was in the first decade, and high-frequency hearing was more severely affected. There was no vestibular involvement. MPZL2 encodes myelin protein zero-like 2, an adhesion molecule that mediates epithelial cell-cell interactions in several (developing) tissues. Involvement of MPZL2 in hearing was confirmed by audiometric evaluation of Mpzl2-mutant mice. These displayed early-onset progressive sensorineural HI that was more pronounced in the high frequencies. Histological analysis of adult mutant mice demonstrated an altered organization of outer hair cells and supporting cells and degeneration of the organ of Corti. In addition, we observed mild degeneration of spiral ganglion neurons, and this degeneration was most pronounced at the cochlear base. Although MPZL2 is known to function in cell adhesion in several tissues, no phenotypes other than HI were found to be associated with MPZL2 defects. This indicates that MPZL2 has a unique function in the inner ear. The present study suggests that deleterious variants of Mplz2/MPZL2 affect adhesion of the inner-ear epithelium and result in loss of structural integrity of the organ of Corti and progressive degeneration of hair cells, supporting cells, and spiral ganglion neurons.

Keywords: MPZL2, deafness, hearing impairment, Deiters cells, cochlea, hair cells, mouse, human

Introduction

The identification of genes associated with hereditary nonsyndromic hearing impairment (NSHI) has accelerated in the last decade with the introduction of next-generation sequencing. But despite the fact that currently more than 100 deafness-associated genes are known (Hereditary Hearing loss Homepage; see Web Resources), more than 60 percent of subjects with hereditary NSHI still cannot be genetically diagnosed.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 These individuals and their relatives receive suboptimal care because of insufficient counseling on prognosis and recurrence risk. In addition, syndromic features can be overlooked, or in the opposite case, health-care providers perform unnecessary and costly tests to screen for additional symptoms that are not present.

Given the number of deafness loci for which the associated gene is not known yet (Hereditary Hearing loss Homepage), it is estimated that many monogenic forms of NSHI still await identification. Discovery of these NSHI-associated genes will contribute to the full understanding of the complex physiology of hearing. However, the search for genes associated with deafness has become more challenging because most frequently involved genes are already known and those that remain are most likely involved in less than 1 percent of the cases, or even in only one or a few families with NSHI. Also, identification of deleterious variant(s) in a single family in a gene not yet associated with NSHI is insufficient proof for causality. Functional studies and animal models are important tools for providing evidence for involvement of the identified gene in hearing.7, 8

In this study, we report the identification of an NSHI-associated gene, MPZL2 (MIM: 604873), by combining homozygosity mapping and whole-exome sequencing (WES) of a family of Dutch origin. Subsequent screening of a phenotype-matched cohort and analysis of WES data of genetically undiagnosed individuals with NSHI led to the identification of two additional families of Turkish origin with truncating variants in MPZL2. We characterized the phenotype of affected individuals and of mice with an intragenic deletion of Mpzl2.9 In addition, we observed histological abnormalities in the cochleae of the mutant mice.

Subjects and Methods

Subject Evaluation

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Radboud University Medical Center and is in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal representatives.

Medical history was obtained from all participants via a questionnaire focusing on hearing and balance, as well as possible acquired causes of HI. Otoscopy was performed in all subjects so that the tympanic membrane and aeration of the middle ear could be assessed. Pure-tone audiometry was performed in a sound-treated room according to current standards. Air conduction thresholds were determined at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 kHz in dB HL. Bone conduction thresholds were determined at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 kHz in dB HL, so that conductive HI could be excluded. HI was described according to the recommendations of the GENDEAF study group.10 Progression of HI was evaluated by cross-sectional linear regression analysis of last-visit audiograms of the better-hearing ear and used for construction of age-related typical audiograms (ARTAs), as described previously.11 Individual progression of HI was calculated for each frequency with longitudinal linear regression analyses via GraphPad Prism 6.0. Tympanometry was performed, and click-evoked ABR and otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) were obtained according to current standards. Contralateral and ipsilateral acoustic reflexes were measured at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz up to the loudness discomfort level. Speech-perception thresholds and maximum speech-recognition scores were determined with speech audiometry, which was performed in a sound-treated room with standard monosyllabic consonant-vowel-consonant Dutch word lists.12

Vestibular function was assessed with electronystagmography (ENG) rotary chair stimulation and caloric irrigation testing according to current standards. Additionally, cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (cVEMPs) and video head impulse tests (vHITs) were performed so that sacculus and vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) functionality, respectively, could be assessed. For assessing the presence of polyneuropathy, standardized neurological screening was performed in accordance with a predefined protocol (Supplemental Methods). Screening for Immunological and corneal defects was performed as described in the Supplemental Methods.

Description of Subject Cohorts

Two cohorts, a phenotype-based cohort and a WES cohort, were screened for the presence of MPZL2 variants. The phenotype-based cohort consisted of 120 individuals with a phenotype comparable to that of individuals of family W05-682, affected members of which demonstrated sensorineural NSHI and a flat, cookie-bite or downsloping audiogram configuration. Of these, 57 subjects were Dutch and displayed stable, mild to severe NSHI; 63 subjects were Spanish and displayed mild to profound NSHI. Only isolated cases and subjects with suspected autosomal-recessive inheritance were included. All subjects were previously tested for a phenotype-based selection of single genes.

The WES cohort consisted of 270 subjects who had presumed recessive HI and for whom WES had been performed previously in a clinical diagnostic setting. In these subjects, pathogenic variants in genes known to be associated with HI (gene panels DGD 200614, DG2.4x or DG2.5/2.6) were excluded by targeted analysis of WES data, as described previously.6 Gene lists and coverage in WES are available at the Genome Diagnostics Radboudumc homepage (see Web Resources). Variants in genes of the panels were classified according to the guidelines from the Association for Clinical Genetic Science and the Dutch Society of Clinical Genetic Laboratory Specialists.13 Subjects were not preselected on the basis of their HI phenotype.

Homozygosity Mapping

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes by standard procedures. The samples of subjects II:1 and II:3 of family W05-682 (Figure 1) were genotyped with the Affymetrix mapping 250K SNP array according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Genotype calling was performed with the Genotyping Console software (Affymetrix) under default settings. Homozygosity mapping was performed with the online tool HomozygosityMapper14 so that significant shared homozygous regions could be identified. Other shared homozygous regions larger than 1 Mb and regions of shared heterozygous genotypes were identified manually.

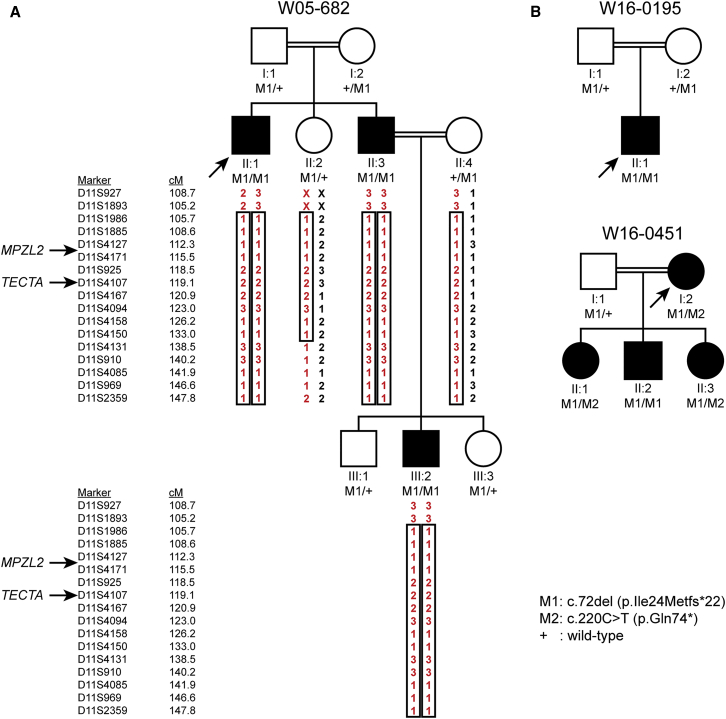

Figure 1.

Pedigrees, VNTR Genotypes and Segregation of Variants of MPZL2

(A) Genotypes of VNTR markers and segregation of identified truncating variants of MPZL2 in family W05-682. Besides MPZL2, TECTA (DFNB21) is also located within the homozygous region shared by the affected individuals. Pathogenic variants in the coding and intronic regions of TECTA were excluded.

(B) Pedigrees and segregation analyses of two additional families with deleterious variants in MPZL2. Index cases are indicated by arrows. Double lines indicate consanguinity (for extended pedigrees, see Figure S1).

VNTR Marker Analysis

Genotyping of variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) markers was performed by DNA amplification with touchdown PCR and analysis on an ABI Prism 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Primers for amplification of VNTR loci were designed with Primer3Plus. Genetic location of the markers was derived online from the Marshfield genetic map, and marker order was confirmed in the human genome assembly GRCh37/hg19. Alleles were assigned with GeneMapper v.4.0 software according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems).

Whole Exome Sequencing

Exome DNA was enriched using the Agilent SureSelect version 4, 5, or 6 kit. WES was performed on an Illumina HiSeq system by BGI-Europe (Denmark). The index cases of families W05-682, W16-0195, and W16-0451 were reanalyzed for an updated gene panel for HI (panel DG2.11) as described in the section “Description of Subject Cohorts.” Copy-number variation (CNV) was evaluated by depth-of-coverage analysis with CONIFER as described.15, 16 Mean ≥20x coverage per sample was 95.9% to 96.5% of the enriched regions. Variants were regarded as rare if the minor-allele frequency (MAF) was ≤1% in the in-house database of ∼15,000 exomes and if the MAF was ≤1% in gnomAD. Prediction of deleterious effects of missense variants and prediction of an effect on splicing were performed as described in the Supplemental Methods.

Sanger Sequencing

Primers for amplification of exons and exon-flanking intronic sequences of MPZL2 (GenBank: NM_005797.3) and TECTA (ENST00000392793, MIM: 602574) and primers for mRNA analysis of TECTA were designed with Primer3Plus and Oligo Primer Analysis Software. Amplification by PCR was performed under standard conditions. DNA isolated from peripheral blood samples was employed for analysis of exons and exon-flanking intronic DNA of MPZL2 and TECTA. For TECTA mRNA analysis, total RNA was isolated from Epstein-Barr-virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cells of affected subjects II:1 and II:3 of family W05-682 with the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Machery Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Poly A+ RNA was isolated from total RNA with the OligoTEX mRNA Spin Column kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and 0.5 μg poly A+ RNA as a starting material, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCRs were performed on 2 μL cDNA with Taq DNA polymerase (Roche). PCR fragments were purified with ExoI/FastAP or ExoSAP-IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with manufacturers’ protocols. Sequence analysis was performed with the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing v.2.0 Ready Reaction kit and analyzed with the ABI PRISM 3730 DNA analyzer or the 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Possibly deleterious effects of the identified variants on the MPZL2 and TECTA proteins and on splicing were predicted with Alamut Visual (Interactive Biosoftware). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are provided in Table S1.

Quantitative PCR Analysis for Identification of Intragenic Deletions and Determination of MPZL2 Expression in Human Tissues

Genomic quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as described in the Supplemental Methods. For analysis of transcript levels, total RNA derived from fetal heart, skeletal muscle, lung, brain, colon, kidney, stomach, spleen, and thymus and from adult skeletal muscle, liver, duodenum, stomach, spleen, thymus, and testis was purchased from Stratagene. Adult heart, lung, brain, kidney, bone marrow, and placenta total RNA was purchased from BioChain. In addition, total RNA was isolated from fetal cochlea (8 weeks of gestation) as described previously.17 Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed with the SuperScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 2 μg total RNA as starting material, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Specification on primer design, the qPCR system, and reaction mixtures are indicated above and in the Supplemental Methods. Primer sequences and conditions are provided in Table S1. The human beta glucuronidase gene (GUSB, MIM: 611499) was employed as a reference gene. All reactions were performed in duplicate. Relative gene expression levels were determined with the delta-delta Ct method.18

Audiometric Characterization of Mpzl2-Mutant Mice

Hearing was evaluated in C57BL6J wild-type (WT) and Mpzl2-mutant mice.9 In these mutant mice, exons 2 and 3 of Mpzl2 were deleted by standard gene-targeting methods.9 This is predicted to result in an in-frame deletion of the coding sequences for amino acid residues 20–145, encompassing part of the signal sequence and the majority of the extracellular region of the 215 residue MPZL2 protein (cf. Figure S1). The strain was described as Mpzl2ko/ko, although RT-PCR on liver RNA and Sanger sequencing of the amplicon confirmed transcript splicing of exon 1 to exon 4 as the only detectable splicing event in the mutant mice (P.S., unpublished data). The presence of the shortened protein in tissues of the mutant mice remains to be determined.

Auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) were registered in 4-, 8-, and 12-week-old mice (n = 5 per genotype and age group), essentially as reported by Cediel et al. (2006)19 with the modifications reported by Murillo-Cuesta et al. (2015).20 In brief, ABR recordings were obtained under anesthesia with ketamine (75 mg/kg, Imalgene, Merial) and xylacine (5 mg/kg, Rompun, Bayer). Click (0.1 ms, 30 pps rate) and tone-burst stimuli (8, 16, 20, 28, and 40 kHz, 5 ms, 50 pps rate) were generated with SigGenRP software (Tucker-Davis Technologies). Stimuli were presented from 90 to 10 dB, relative to sound pressure level (dB SPL) in 5–10 dB SPL steps with a MF1 speaker (TDT). The electrical responses were amplified, recorded, and averaged, and hearing thresholds were determined in the ABR recordings. Amplitudes of ABR waves I, II, and IV and interpeak latencies of peaks I-II, II-IV, and I-IV were analyzed for 70 dB SPL click stimuli.

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS 23.0 software. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used for compaing ABR parameters between genotypes because of the small sample sizes. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with Spanish and European legislation and approved by the local bioethics committees.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry of Cochleae from Wild-Type and Mpzl2-Mutant Mice

Histology and immunohistochemistry were performed according to standard protocols, which are detailed in the Supplemental Methods. Antibodies used were the following: primary antibodies, rabbit anti-Kir4.1 (AB5818 Chemicon), rat anti-ZO-1 (sc-33725, Santa Cruz); rabbit anti-KCNQ1 (sc-20816, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-Myosin VIIa (25-6790, Proteus), and goat anti-SOX2 (sc-17320, Santa Cruz). Rabbit anti-MPZL2, raised against the complete protein (11787-1-AP, Proteintech), goat anti-Collagen IV (1340-01, SouthernBiotech), and mouse anti-Na+-K+ATPase α1 (α6F, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). The following served as secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor (AF) conjugated immunoglobulins (Molecular Probes): AF 568-goat anti-rabbit (A11011), AF 488-donkey anti-goat (A11055), AF 488-goat anti-mouse (A11029), and AF 488-goat anti-rat (A11006).

Results

Homozygosity Mapping and WES Revealed Loss-of-Function Variants of MPZL2

Homozygosity mapping in a Dutch consanguineous family in which some members had autosomal-recessive NSHI (W05-682; Figure 1 and Figure S2) revealed a single significant homozygous region of 23.8 Mb on chromosome 11q23.1-q25, flanked by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs4936310 and rs10458997 (Figure S3). VNTR marker analysis confirmed homozygosity of the region, and segregation of marker alleles in the family was compatible with linkage of the HI with a region that was flanked by D11S1893 at the centromeric side and included D11S2359 at the telomeric side (Figure 1A). D11S2359 is the most telomeric VNTR marker of chromosome 11q (UCSC Genome Browser, GRCh37/hg19). Combining VNTR marker and SNP data delimits the critical region to Chr11: 110,803,280–134,746,130. Two hundred and nine RefSeq genes, including TECTA, a known deafness-associated gene, have been annotated in this region (UCSC Genome Browser, GRCh37/hg19). However, pathogenic variants in TECTA were excluded by Sanger sequencing of all exons and exon-intron boundaries and by mRNA analysis. The homozygous region did not contain or overlap with any other genes or loci known to be associated with deafness. Fourteen additional homozygous regions larger than 1 Mb and shared by individuals II:1 and II:3 were identified (Table S2). There were no regions with shared heterozygous genotypes larger than 1 Mb.

As a next step, WES was performed in the index case (II:1) of family W05-682. The mean ≥20x coverage of genes in the homozygous region of chromosome 11q23.1–q25 was 98.1%. Variants were filtered as indicated in Figure S4 and classified as described in the Supplemental Methods (Table S3). Three rare homozygous variants in coding sequences and splice sites were present in the 23.8 Mb homozygous region. The BSX (MIM: 611074) variant c.263−5T>C (p.?) (GenBank: NM_001098168.1) was predicted not to affect splicing. The missense GRAMD1B variant c.1111G>A (p.Val371Ile) (GenBank: NM_001286563.1) was predicted to be pathogenic by two of the four tools (Table S3). The third variant was a homozygous one-base-pair MPZL2 deletion, c.72del (GenBank: NM_005797.3, Figure S5), that is predicted to result in premature termination of protein synthesis (p.Ile24Metfs∗22). Because MPZL2 was known to be transcribed in the cochlea at a significant level and the variant was truncating, it seemed the most promising candidate gene.21, 22 The MPZL2 variant c.72del, with a global minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.00077 and a MAF of 0.00127 in the non-Finnish European population, has only been reported heterozygously in gnomAD. The variant is reported to be most common in Ashkenazi Jews (MAF 0.00375). Segregation analysis by Sanger sequencing demonstrated co-segregation of the variant and HI in the family (Figure 1A), which was also true for the variants of BSX and GRAMD1B. Targeted analysis of WES data for a panel of 142 HI-associated genes revealed no other (likely) pathogenic variants. Also, no CNVs of the 142 HI-associated genes were detected, and thus no CNVs of TECTA were detected either. There were also no CNVs detected in the 23.8 Mb region. Exonic and flanking intronic sequences of TECTA were fully covered (≥15x). All detected variants of this gene are displayed in Table S4. None of the homozygous variants that occurred outside of the 23.8 Mb homozygous region and that were predicted to be pathogenic by two or more prediction tools co-segregated with the disease in the family (Table S3).

Identification of Additional Families with Deleterious MPZL2 Variants

We addressed further involvement of MPZL2 variants in recessive NSHI. A phenotype-based cohort of 120 unrelated probands with a phenotype similar to that of affected individuals in family W05-682 was screened for variants of MPZL2. This revealed the variant c.72del (p.Ile24Metfs∗22) in a homozygous state in a family of Turkish origin, W16-0195. The variant was present heterozygously in the unaffected consanguineous parents (Figure 1B, Figure S5).

In two other individuals of the phenotype-based cohort, rare heterozygous MPZL2 variants, namely c.268C>T (p.Arg90Trp) and c.544C>T (p.Arg182∗), were identified. So that possible intragenic deletions of the second allele could be identified, genomic qPCR was performed for exons in which no heterozygous SNPs were detected (Table S5). No deletions were identified. Therefore, defects of MPZL2 are unlikely to be causative of HI in these subjects. However, a deleterious variant in non-coding regions of the gene cannot be excluded.

Subsequently, data of a WES cohort of 270 genetically undiagnosed NSHI subjects were analyzed for rare MPZL2 variants. This unveiled a third family, W16-0451, that was of Turkish origin and had truncating variants in MPZL2. Segregation analysis demonstrated that the c.72del and c.220C>T (p.Gln74∗) variants were present in compound heterozygous state in the index case and that her affected offspring also carried biallelic truncating MPZL2 variants (Figure 1B, Figure S5). The c.220C>T variant has been reported only heterozygously in gnomAD; it has a global MAF of 0.00038 and an MAF of 0.00003 in the non-Finnish European population, which represents a significant part of the Turkish ancestry.23 The MAF of c.220C>T is 0.00515 in the East Asian population and 0.00016 in the South Asian population, as indicated in gnomAD. There is admixture of the Turkish population from Asia, mainly from West and Central Asia.23 The c.220C>T variant has not been observed in other populations represented in gnomAD. WES data of the index case of family W16-0451 were reanalyzed for the updated panel of 142 HI-associated genes. This analysis was also performed for WES data of individual II:3. Neither of the two subjects had any potentially causative variants or CNVs of these genes and did not share rare CNVs in the remaining part of the exome. So that other variants that might underlie HI in family W16-0451 could be identified, rare variants homozygous in both individual I:2 and individual II:3 were evaluated, as were potentially compound heterozygous variants (Table S6). Segregation analysis of the candidate variants predicted to be pathogenic revealed that only the homozygous PRDM2 (MIM: 601196) variant c.861_863del (GenBank: NM_012231.4; p.Asp287del) co-segregated with the disease. There were no variants that were homozygous in individual I:2 or II:3 and also potentially compound heterozygous in the other individual. Although the PRDM2 transcript level in adult human cochlea (FPKM 58-73) is significant and is comparable to that of MPZL2 (FPKM 35-83),22 no HI has been reported for homozygous Prdm2-knockout mice (targeted) in the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database, and ABR measurements of mice with an intragenic deletion of Prdm2 revealed normal hearing, as reported by the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC). Therefore, the variant of PRDM2 is unlikely to explain the HI in family W16-0451.

The c.72del MPZL2 Variants Are Derived from a Common Founder

VNTR marker analysis was performed in families W05-682, W16-0195, and W16-0451 so that the haplotypes in the MPZL2 region could be determined (Figure S6). All c.72del MPZL2 alleles shared a haplotype of at least 0.5 Mb, delimited by markers D11S1341 and D11S4104, suggesting that it is a founder variant rather than a recurrent variant due to a mutational hotspot. Because the families have a different ethnic background, the c.72del variant is likely to be of ancient origin.

Clinical Characterization of Individuals with Pathogenic Variants of MPZL2

All affected and unaffected subjects of families W05-682, W16-0195, and W16-0451 underwent clinical examinations. One of the siblings (II:1) of family W16-0451 was not able to participate in the current clinical evaluation; only retrospective data of this subject were used for analysis. History revealed that this individual previously underwent surgery for cholesteatoma of the left ear. Therefore, audiometric data of the right ear only were used for this study, and these data showed pure sensorineural HI. However, she also had osteogenesis imperfecta, which might contribute to her sensorineural HI. Nevertheless, her hearing thresholds were very similar to age-matched hearing thresholds of other affected family members, and therefore we decided to include her in the audiometric evaluations.

None of the affected subjects (family W05-682, II:1, II:3, and III:2; family W16-0195, II:1; family W16-0451, I:2, II:1, II:2, and II:3) demonstrated abnormalities on otoscopy and tympanometry (Table S7). Pure-tone audiometry of these individuals revealed no signs of conductive HI but did demonstrate a symmetric mild to moderate HI with a gently downsloping audiogram configuration for all of them (Figure 2A). The mean reported onset age of HI was 4 years (min–max: 3–9 years) (Table S8). Four affected individuals had a disturbed speech-language development, whereas development was normal in three cases and unknown in one case. Speech perception thresholds were lower than the pure-tone average thresholds at 0.5, 1, and 2 kHz, and maximum speech-recognition scores were 90%–100% for the better-hearing ear, both suggesting absence of retrocochlear pathology. Acoustic reflexes were present (both ipsilateral and contralateral) without decay, which also suggested an absence of retrocochlear pathology. OAEs could only be detected in individuals II:2 and II:3 of family W16-0451, for frequencies with hearing thresholds lower than 30 dB HL. This is indicative of residual function of cochlear OHCs.24 OAEs were absent in all other affected subjects. The index cases of families W05-682 and W16-0195 displayed normal ABR wave latencies, which indicated normal auditory neural processing. Additional information on otologic and audiometric evaluation of individual cases is provided in Table S7.

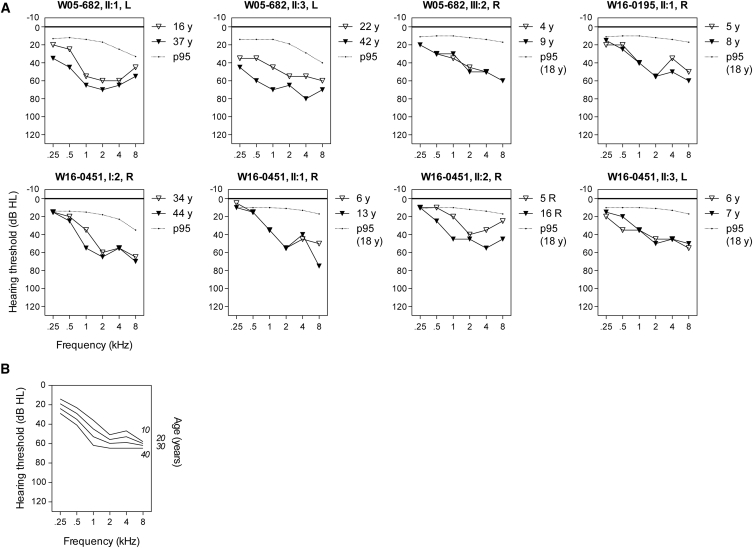

Figure 2.

Audiometric Characterization of Families Affected by Pathogenic MPZL2 Variants

(A) Air-conduction thresholds of the better-hearing ear of all affected individuals. The better-hearing ear was determined from calculations of the mean of the pure-tone thresholds for 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz of the last audiogram. First-visit and last-visit audiograms are depicted. Subject II:1 of family W16-0451 was not able to participate in the clinical evaluation; only retrospective data for this subject were used for analysis. R, right ear; L, left ear.

(B) ARTA (age-related typical audiogram) constructed by cross-sectional linear-regression analysis of last-visit audiograms of all affected individuals (n = 8).

Individual longitudinal regression analyses of hearing thresholds revealed that HI was progressive in all affected adults. No progression could be demonstrated in the affected children, for whom follow-up time (1–11 years) was probably too short for significant progression to be established. Cross-sectional linear-regression analysis revealed progression of HI for all frequencies. The increase of hearing thresholds was significant at 1 kHz (0.8 dB/year), 2 kHz (0.5 dB/year), and 4 kHz (0.6 dB/year). In Figure 2B, the ARTA is depicted, which demonstrates gradual progression of HI.

None of the affected subjects or their parents reported vestibular symptoms, such as vertigo, dizziness, instability, or delayed motor development, except for the index case of family W16-0451 (I:2), who reported two periods of vertigo in the past without persisting complaints. Vestibular function was assessed in three of the hearing-impaired individuals (family W05-682, II:1; family W16-0451, I:2 and II:2), and normal to slightly hyperreactive vestibular responses were measured (Table S8).

Because MPZL2 is highly homologous to MPZ (MIM: 159440), which is associated with distinct types of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 we performed neurological screening of the affected individuals (family W05-682, II:1, II:3, and III:2; family W16-0195, II:1; and family W16-0451, I:2, II:2, and II:3). No symptoms or signs of neuropathy were present.

Hearing-impaired subjects were also screened for immunological abnormalities because MPZL2 is involved in early thymocyte development.32, 33, 34 None of them had symptoms of immunodeficiency, allergies, or autoimmune disease. CD4 and CD8 T cell counts, including double-positive (CD4+CD8+) and double-negative (CD4−CD8−) cell counts, as well as the CD4/CD8 ratios, were normal (Figure S7), indicating normal CD4 and CD8 expression on T cells.

Because gene expression studies have shown that MPZL2 transcript levels are relatively high in the cornea of the eye (Ocular Tissue Database),35 affected individuals were screened for corneal abnormalities. There were no eye problems, slit lamp biomicroscopy did not show abnormalities, and visual acuity was normal.

MPZL2 Is Expressed in Human Fetal Cochlea

The relative expression of MPZL2 was determined in human fetal cochlea and various other fetal and adult human tissues (Figure S8). Because the fetal tissues were not derived from embryos of the same gestational age, mRNA transcript levels are not directly comparable. Among the tested fetal tissues, MPZL2 expression was highest in the inner ear, where transcript levels were 70-fold higher than in skeletal muscle, which displayed the lowest detectable expression. Also, in all other fetal tissues MPZL2 transcript levels were significantly lower than those in the inner ear. In the analysis of MPZL2 expression in adult tissues, mRNA levels of MPZL2 in the fetal inner ear were included for comparison. MPZL2 mRNA was detected in all analyzed adult tissues, and the highest levels were in the thymus and lung, whose levels were in the range of those in fetal inner ear.

Mpzl2-Mutant Mice Are Hearing Impaired

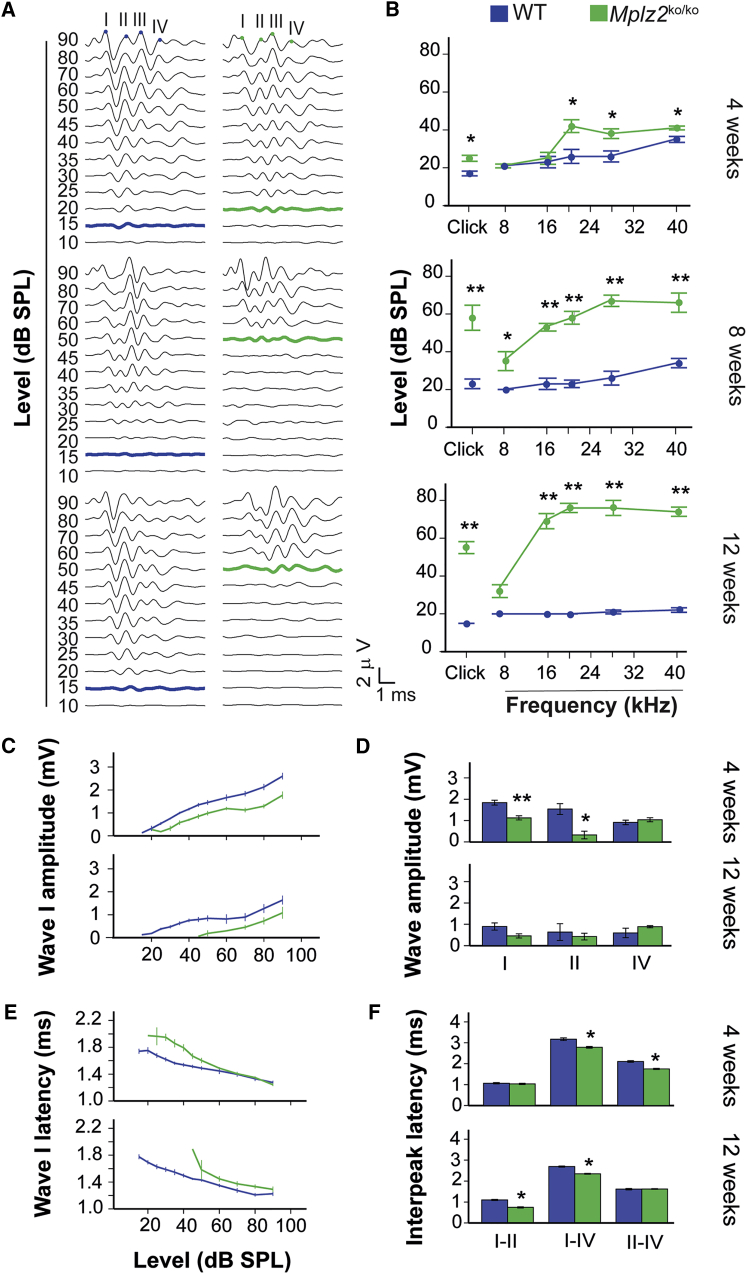

Mpzl2-mutant mice showed early-onset progressive HI and significantly increased ABR thresholds in response to click and tone-burst stimuli in the ages studied, when these mice were compared to age-matched C57BL6J, normal-hearing wild-type mice. Four-week-old mutant mice showed a mild HI that affected the detection of click stimuli and pure-tone frequencies above 16 kHz (Figures 3A and 3B) at statistically significant higher thresholds (p < 0.05) than for wild-type mice. HI in mutant mice rapidly progressed to moderate and severe at the ages of 8 and 12 weeks, respectively, and these mice had statistically significant elevated thresholds for all tested stimuli in comparison to wild-type mice. At 12 weeks of age, ABR thresholds in response to 16–40 kHz are above 70 dB SPL in the mutant mice, whereas wild-type mice maintained normal hearing at thresholds below 30 dB SPL. Accordingly, significant alterations in ABR peak amplitudes, latencies, and interpeak latencies were observed in mutant mice. The maximum amplitudes of wave I, which represents cochlear activity, were approximately 30% lower in the knock-out animals than in the wild-type mice at all ages studied (Figure 3C), and differences reached significance in 4-week-old mice (Figure 3D). In addition, wave I peaks showed increased latencies in the mutants as compared to wild-type mice, which progressed over time. Peaks were increased in young animals (4 weeks old) at the level of intensity near the threshold, whereas in 12-week-old mice they were increased for all intensities tested (Figure 3E). Also, mutant mice showed significantly shorter interpeak latencies (IPLs) I-II, II-IV, and I-IV than wild-type mice (Figure 3F). These data suggest a compensatory central response to the delayed peripheral transmission, as already shown in the Igf1 knockout.36

Figure 3.

Hearing Phenotype of Mpzl2-Mutant (Mpzl2ko/ko) Mice

(A) Representative click-evoked ABR recordings at decreasing intensities (dB SPL) in 4-, 8-, and 12-week-old wild-type and Mpzl2-mutant mice. Waves are labeled I–IV and reflect the evoked activity of the auditory nerve (I) and ascending points of the auditory pathway in the midbrain (II–IV). As the stimulus level is reduced, amplitudes of ABR waves decrease and latencies of waves increase. The lowest intensity at which the ABR-wave profile is higher than the background-noise signal is the threshold (bold line; WT, blue; Mpzl2-mutant mice, green).

(B) ABR thresholds, in response to click and 8–40 kHz tone bursts, of the different genotypes and age groups.

(C and E) ABR wave I amplitude/intensity (C) and latency/intensity (E) curves in response to click stimuli of increasing intensities were determined in 4- and 12-week-old wild-type and Mpzl2-mutant mice.

(D and F) Peak amplitude of ABR waves I, II, and IV (D) and interpeak latencies I-II, II-IV, and I-IV (F) in response to a 70 dB SPL click stimulus in 4- and 12-week-old wild-type and Mpzl2-mutant mice. Data are shown as means ± SEM. Statistical significance: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

Mpzl2-Mutant Mice Display Alterations in Cell Organization and Cell Loss in the Organ of Corti

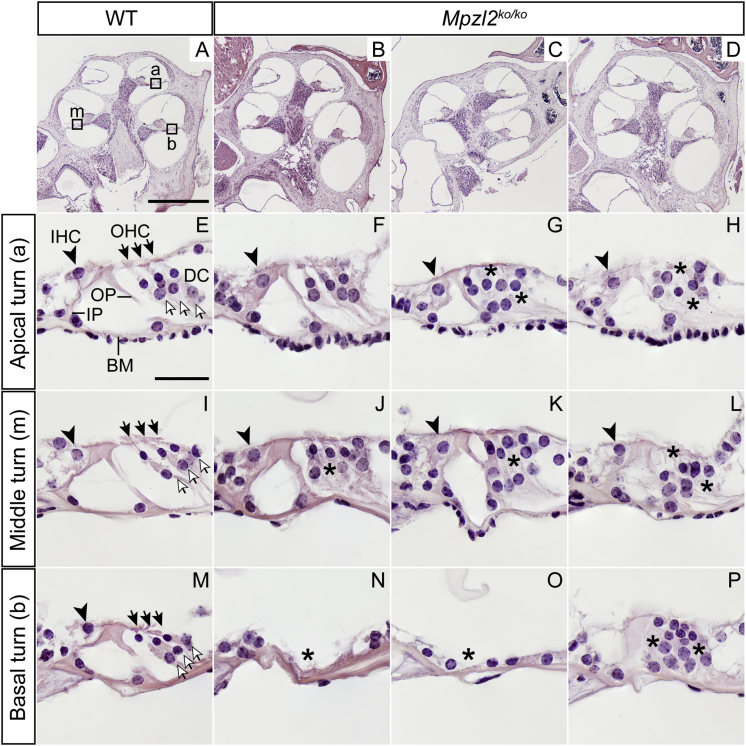

We evaluated the general cochlear cytoarchitecture in the basal, medial, and apical turns of the cochlea of 12-week-old mice (Figure 4 and Figure S9) to assess the integrity of the principal structures. Namely, we looked at the organ of Corti with inner and outer hair cells (IHCs and OHCs, respectively) responsible, respectively, for the mechanotransduction and amplification and tuning of the sound, and we looked at different types of supporting cells. Furthermore, we evaluated the spiral ganglion neurons that connect the hair cells with the central auditory pathway; the stria vascularis, involved in the formation of the high-potassium-containing endolymph, in the lateral wall; and the spiral ligament. Loss of hair and supporting cells of the organ of Corti (asterisk in Figure S9D) and of neurons in the spiral ganglion (asterisks in Figure S9D-1) were observed in the basal cochlear turn of mutants, but not in wild-type mice. No evident structural abnormalities were seen in the stria vascularis or spiral ligament. Markers of the stria vascularis were not altered in mutant mice, as compared to age-matched wild-type animals (Figure S10).

Figure 4.

Cochlear Morphology of 12-Week-Old Wild-Type and Mpzl2-Mutant (Mpzl2ko/ko) Mice

Microphotographs show representative midmodiolar cross sections of the cochlea from one representative wild-type mouse (A) and three Mpzl2-mutant mice (B–D). The apical (a), middle (m), and basal (b) organs of Corti are boxed in image (A). Close-ups of the organ of Corti from one wild-type mouse (E, I, and M) and three Mpzl2-mutant mice (F–H, J–L, and N–P) are shown. Arrowheads point to inner hair cells (IHCs), blackhead arrows to outer hair cells (OHCs), and arrows to Deiters cells (DCs). BM, basilar membrane; IP, inner pillar cell; and OP, outer pillar cell. Asterisks mark abnormalities. The scale bars represent 500 μm (A–D) and 25 μm (E–P).

A closer evaluation of the organ of Corti (Figure 4) showed clear differences between wild-type and Mpzl2-mutant mice at 12 weeks of age. At the basal turn of the cochlea, two mutant mice showed a flat epithelium at the basilar membrane; there was complete loss of hair and supporting cells (asterisks in Figure 4N and Figure 4O). At the medial and apical turns of the cochlea, hair and supporting cells were present in both genotypes, as were tunnel-forming inner and outer pillar cells (IPs and OPs, respectively) (Figure 4E). However, mutant mice showed an aberrant mosaic pattern of OHCs and supporting Deiters’ cells (DCs; the spaces between OHCs had collapsed, and DC nuclei were displaced with respect to OHC nuclei (asterisks in Figures 4G, 4H, 4J–4L, and 4P).

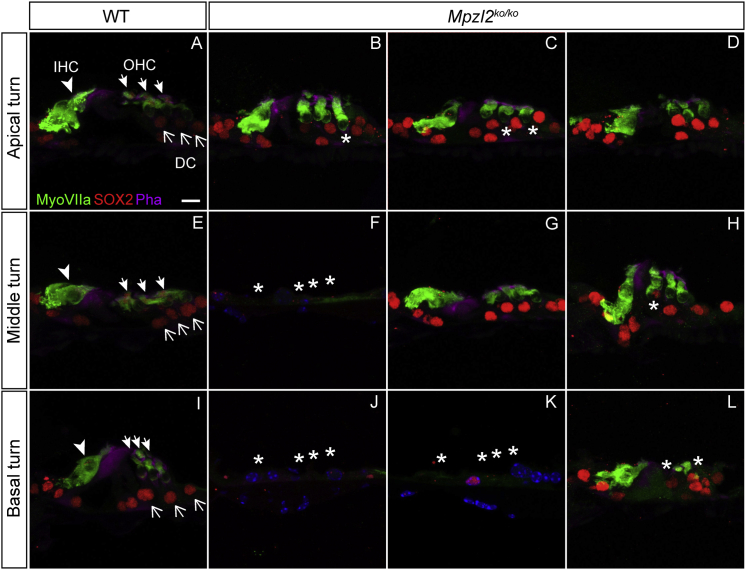

Specific immunolabeling for Myosin VIIa and SOX2 evidenced that IHCs, OHCs, and supporting cells were present. Also, this analysis confirmed that mutant mice display a disorganized arrangement of OHCs and DCs in the apical (asterisks in Figures 5B and 5C) and middle (asterisk in Figure 5H) turns and that they display decreased numbers or an absence of all cell types in the basal turn of the cochlea (asterisks in Figures 5J–5L), in comparison to wild-type mice. Statistically significant differences were found in the number of OHCs in the basal turn only because of the differences in severity of the phenotype in mutant mice (Figure S11). At P4, no indications were obtained for an abnormal cellular organization in the developing organ of Corti (Figure S12).

Figure 5.

Organ-of-Corti Cytoarchitecture of Wild-Type and Mpzl2-Mutant (Mpzl2ko/ko) Mice

Close-ups of the organ of Corti from representative frozen sections (10 μm) prepared from one representative wild-type mouse (A, E, and I) and three Mpzl2-mutant mice (B–D, F–H, and J–L). Hair cells and supporting cells were immunolabeled for Myosin VIIa (green) and SOX2 (red), respectively, in the apical, middle, and basal turns of the cochlea. Actin in the organ of Corti was stained with phalloidin (purple). Arrowheads point to inner hair cells (IHCs), whitehead arrows to outer hair cells (OHCs), and arrows to Deiters cells (DCs). Asterisks mark abnormalities. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

Mouse MPZL2 Is Present in the Organ of Corti and the Stria Vascularis

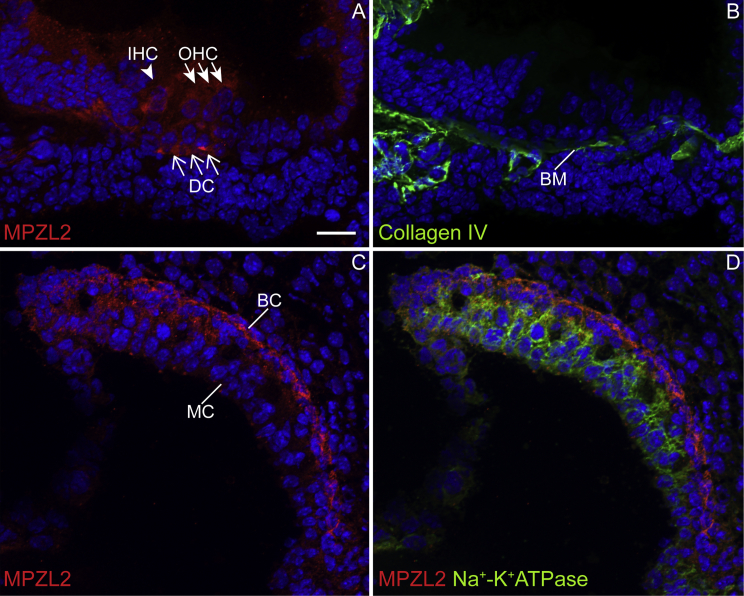

Cochlear expression and localization of MPZL2 was assessed in wild-type mice at P4 by immunofluorescence, which revealed a signal in DCs and, most intensely, in the basal region of DCs in all three cochlear turns (Figure 6A and Figure S13). Staining of serial sections with anti-collagen IV suggests that MPZL2 is present where DCs contact the basilar membrane (Figures 6A and 6B). Weaker MPZL2 immunostaining is observed in both IHCs and OHCs (Figure 6A and Figure S13). In the stria vascularis, MPZL2 was detected in the basal cell layer, as confirmed by co-staining with anti-Na+-K+ATPase, which demarcates the intermediate cell layer (Figures 6C and 6D). Specificity of the anti-MPZL2 antibody was confirmed by analysis of cochleae of Mpzl2-mutant mice in the same experiments (Figure S13).

Figure 6.

MPZL2 Displayed a Distinct Localization in the Cochlear Organ of Corti and Stria Vascularis at P4 in Wild-Type Mice

(A) MPZL2 (red) localizes in the organ of Corti in the basal region of Deiters cells (DCs) present below the three rows of outer hair cells (OHCs) and diffusely in inner hair cells (IHCs), OHCs, and DCs.

(B) In a serial section, collagen IV (green) immunostaining marked basement membranes, including the basilar membrane (BM), thereby indicating the localization of MPZL2 at the DC-BM contact region.

(C) In the stria vascularis, MPZL2 (red) immunostaining was observed predominantly in the basal cell (BC) region.

(D) Co-immunostaining of MPZL2 and Na+-K+ATPase (green), a marker for marginal cells (MCs), confirms immunostaining of MPZL2 (red) in the basal cells. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrowheads point to IHC, whitehead arrows to OHCs, and arrows to DCs. The scale bar (A–D) repsresents 20 μm.

Discussion

This study provides evidence for the association of biallelic defects of MPZL2 with recessively inherited sensorineural NSHI in humans and mice. Affected human subjects displayed moderate to severe, slowly progressive HI from the first decade onward, and intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotypic similarity was high. The functional and morphological inner-ear defects in Mpzl2-mutant mice provide important evidence for the causal relationship between MPZL2 defects and HI in the studied families. This is further strengthened by the fact that HI of Mpzl2-mutant mice and affected family members was similar with regard to the early onset, the progressive nature, and the fact that high-frequency hearing was more severely affected than middle- or low-frequency hearing. The latter is reflected by the decreasing severity of disorganization and loss of OHCs and DCs from the cochlear base to apex.37 For other genes that harbored variants that co-segregated with HI in families W05-682 and W16-0451 and were predicted to affect protein function, there are no supporting data for an association with HI. For GRAMD1B (W05-682), which is transcribed in adult human cochlea (FPKM 2.09-8.4422), no phenotyping information on mouse mutants is available in IMPC or MGI databases. No interactions of GRAMD1B with proteins encoded by genes associated with NSHI are reported (STRING or BioGRID).

TECTA (DFNB21, MIM: 603629) was located in the homozygous candidate region of family W05-682. Recessively inherited defects of TECTA can cause moderate-to-severe HI, although with a more flat audiogram configuration than observed in the presented families.38, 39 We scrutinized TECTA for defects in family W05-682, and we excluded (potentially) causative variants in the exonic sequences and splice sites of the gene. We did not obtain any indication for aberrant splicing that might result from deep intronic variants. Only variants in upstream or downstream sequences with a regulatory role in transcription or intronic variants that could cause aberrant splicing specifically in the inner ear could have been missed.

The identified MPLZ2 variants are the most common truncating variants in the gene; they have the highest gnomAD allele frequencies, of 0.0051 for c.220C>T in the East Asian population and 0.00375 for c.72del in the Ashkenazi Jews. For comparison, the c.2299delG founder mutation of USH2A (MIM: 608400) is most common in the latino population (0.0016) and has an allele frequency of 0.001 in non-Finnish Europeans. The most common cause of severe autosomal-recessive NSHI, the c.35delG mutation of GJB2 (MIM: 121011), has a frequency of 0.0097 in non-Finnish Europeans in GnomAD. In light of this, the identification of defects of MPZL2 as a cause of HI only now is surprising because the identified defects are expected to be important causes of HI in East Asia and in the Ashkenazi Jewish communities. Because research efforts were concentrated on severe-to-profound early-onset HI for many years, the association of MPZL2 with HI might have remained undetected because of the mild-to-moderate severity of the HI. Also, because of the relatively mild HI, families might have a lower tendency to consult a genetic counselor or to participate in genetic studies than families in which more severe HI occurs. Furthermore, although not supported by our findings in the presented families, variants of MPZL2 might have a reduced penetrance that could result from (common) modifying genetic variants.

The pLI score40 of MPZL2 is 0.00, which suggests that the gene is tolerant to loss-of-function variation. This is true for many of the HI-associated genes, e.g., MYO7A (MIM: 276903) and USH2A, which have the same pLI score of 0.00. The tool DOMINO41 predicts that MPZL2 is associated with a recessive rather than a dominant disorder, which is in agreement with our findings.

OHCs function as cochlear amplifiers that enhance hearing thresholds by more than 40 dB, and loss of the amplifying function leads to 40–60 dB HI.42, 43 Because subjects with deleterious MPZL2 variants displayed a 35–65 dB increase of hearing thresholds, the HI phenotype is compatible with predominant loss of OHCs. In addition, the remarkably good speech discrimination compared to the hearing thresholds and absence of OAEs in the affected individuals indicate abnormal OHC function.44, 45 Given the only moderate HI of the affected adult subjects of family W05-682 and subject I:2 of family W16-0451 at the age of about 40 years, we hypothesize that IHCs do not degenerate over time or that they do so very slowly.

MPZL2 (myelin protein zero-like 2), alternatively called EVA1 (epithelial V-like antigen 1), is a low-affinity adhesion molecule and a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, more specifically of the family of immunoglobulin-like cell-adhesion molecules (Ig-CAMs).32 Ig-CAMs form a large family of cell-surface molecules broadly expressed in, for example, epithelial and endothelial cells and in the nervous system. Ig-CAMs are known to interact directly with other classes of cell-surface molecules, such as cadherins, integrins, and tyrosine kinase receptors, and intracellularly they interact with cytoskeleton proteins such as actin and ankyrin (for review, see46, 47).

The biological function of MPZL2 is likely to be related to its ability to mediate both homophilic and heterophilic cell-cell adhesions. In mice, Mpzl2 is already expressed early in embryogenesis in various epithelial tissues as well as in adult tissues.32, 48 An adhesive function of MPZL2 has been indicated in thymus histogenesis and T cell development,32, 33 placental morphogenesis,49 the blood-cerebrospinal barrier,50 lymphocyte adhesion to choroid plexus epithelial cells,51 and mammary epithelial-cell differentiation.48 Upregulation of Mpzl2 in spermatogenic cells of mice deficient in cell-adhesion molecule 1 further supports the cell-adhesive function.52 Also, MPZL2 was demonstrated to function in the proliferation and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma-initiating cells53 Despite these manifold indications of functional significance of MPZL2, no phenotypes other than HI were reported to be associated with MPZL2 deficiency.53, 54 This suggests that MPZL2 function is essential only in the inner ear and that functional redundancy might well prohibit phenotypic effects in other tissues. This is similar to what is found for several other HI-assciated genes, e.g., KITLG and SMPX.7, 55 However, more phenotypic effects might emerge under stress conditions, as is suggested by increased severity of experimentally induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis and white-matter tissue injury in MPZL2-deficient mice.54

In the developing and adult inner ear, several CAMs, belonging to different protein families, including the Ig-CAM superfamily, display a specific spatiotemporal pattern of expression, and several of these Ig-CAMs are critical for hearing and/or balance in both mice and humans.56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 The Ig-CAMs nectin-1 and -3, for example, are critical for establishing the checkerboard-like organization of hair cells and supporting cells in the cochlea.64 The abnormal organization of DCs and OHCs, and their loss in Mpzl2-mutant mice at 12 weeks of age indicates that MPZL2 is essential for maintenance of the DC-OHC organization and integrity. A role in maintenance is supported by the moderate transcript levels of MPZL2 in adult human cochleae.22

Although no structural abnormalities were detected in cochleae of Mpzl2 mutants at P4, MPZL2 is likely to function in prenatal cochlear development as well, in both mice and humans, as indicated by the finding that transcription of the gene was demonstrated in human embryos at 8 weeks of gestation and in mouse developing hair cells and their surrounding cells from embryonic day 16 (E16) to P16.65 (See also the SHIELD database.) From the present study it is unclear whether MPZL2-associated HI is congenital or has an early-childhood onset. The fact that speech language development was disturbed in a number of cases indicates that onset of HI was prelingual in these individuals. If HI was congenital in the cases with prelingual HI, thresholds were below 35 dB HL because two of three individuals with prelingual HI passed a neonatal hearing screening. These tests are calibrated to pick up HI of more than 35 dB HL.66

We found MPZL2 to be a CAM that is present specifically at the base of DCs where they contact the basilar membrane. DCs develop a narrow infranuclear region that ends in feet-like junctions with the basal membrane.67 The stripe-shaped signal in DCs in MPZL2 immunohistochemistry might represent the developing feet-like structures. It is tempting to speculate that MPZL2 is involved in the morphogenesis and/or maintenance of the characteristic structure of DCs by anchoring the actin-rich cytoskeletal core of the feet-like structures or the surrounding microtubules to the basilar membrane.67 The relatively weak MPZL2 signal in immunohistochemistry at P4 in OHCs, IHCs, and the cytoplasm of DCs suggests that MPLZ2 (transiently) functions in homophilic or heterophilic cellular junctions of these cells and that absence of these junctions in Mpzl2-mutant mice might contribute to the disorganization and degeneration of the organ of Corti.

Although not much is known about the adhesive function of MPZL2 at the molecular level, some hints toward molecular interactions have been obtained. A co-association of MPZL2 and CLCA2 with tight junction protein ZO-1 has been described.48 ZO-1 is an adaptor protein that functions in the coupling of TJs and adherens junctions (AJs) to the cytoskeleton.68 Also, ZO-1 binds directly to occludin in vitro.62 Interestingly, an association of MPZL2 and occludin has been observed in a high-throughput human protein interaction study.69 Occludin is a tight-junction (TJ) protein essential for functional integrity of the reticular lamina of the organ of Corti.60 The organ of Corti of Occ−/− mice degenerates, starting in the OHC region. Because of these associations and the defects in the organ of Corti in Mpzl2-mutant mice, it is tempting to speculate that MPZL2 is essential for (functional) integrity of cell junctions in the reticular lamina, especially in the OHC region, and thereby for ion homeostasis in the cochlea. The associations of MPZL2 with TJ and AJ proteins and their co-function in the cochlea have to be validated with other protein-interaction assays, as well as co-localization assays in the inner ear. The latter assays were impaired by the failure of antibodies to detect MPZL2 in the experimental conditions to be used in immunofluorescence of adult cochleae.

Recently, it was demonstrated that MPZL2 can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, most likely by binding TRAF2, for which a consensus binding site is present in the cytoplasmic domain of MPLZ2.53 This pathway was indicated to be protective for hair cell loss by environmental factors such as noise and aminoglycosides.70, 71 Therefore, defects of MPZL2 might lead to an increased sensitivity to noise and other environmental cues.

Although MPZL2 was detected in the basal cell layer of the developing stria vascularis, no gross histological abnormalities were observed in this region of the cochlea in Mpzl2-mutant mice, either at the age of 4 days or at 12 weeks of age. However, this does not fully exclude functional defects. A mild loss of spiral ganglion neurons was observed in the basal turn of the cochlea of Mpzl2 mutants; this loss might have been secondary to hair-cell loss.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that MPZL2 is essential for normal cochlear function in humans and mice. In the latter species, defects of MPZL2 resulted in OHC and DC disorganization that is likely to interfere with mechanical and other functional properties of that region of the cochlea and ultimately in a loss of integrity of the organ of Corti. Humans affected by biallelic truncating MPZL2 variants displayed slowly progressive NSHI, which is important in (genetic) counseling of subjects and their families.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consortia

The DOOFNL consortium consists of M.F. van Dooren, H.H.W. de Gier, E.H. Hoefsloot, M.P. van der Schroeff, S.G. Kant, L.J.C. Rotteveel, S.G.M. Frints, J.R. Hof, R.J. Stokroos, E.K. Vanhoutte, R.J.C. Admiraal, I. Feenstra, H. Kremer, H.P.M. Kunst, R.J.E. Pennings, H.G. Yntema, A.J. van Essen, R.H. Free, and J.S. Klein-Wassink.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participating patients and their families. We thank Jeroen van Reeuwijk for discussions. We also acknowledge the experimental contributions of L. Hetterschijt, S. van der Velde-Visser, and E. de Vrieze and the technical assistance of the histology facilities (Centro Nacional de Biotecnología, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas [CSIC], and the Center for Biomedical Network Research on Rare Diseases [CIBERER]) and of the Non-invasive Neurofunctional Evaluation and Genomics facilities (IIBm, CSIC-UAM [Universidad Autónoma de Madrid], and CIBERER). This work was supported by a grant from the Heinsius Houbolt Foundation (to H.K., R.J.E.P., and H.P.M.K.) and partially by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the European Regional Development Fund (Fonds Européen de Développement Économique et Régional, [FEDER]: SAF2014-53979-R) and from FEDER, CIBERER, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (to I.V.N.), and a grant from ISCIII to I.d.C. (PI14/01162; Plan Estatal de I+D+I 2013-2016, with co-funding from the European Regional Development Fund). S.M., A.M.C., and E.G.R. hold CIBERER ISCIII researcher contracts.

Published: June 28, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include Supplemental Methods, 13 figures, and seven tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.05.011.

Contributor Information

Hannie Kremer, Email: hannie.kremer@radboudumc.nl.

DOOFNL Consortium:

M.F. van Dooren, H.H.W. de Gier, E.H. Hoefsloot, M.P. van der Schroeff, S.G. Kant, L.J.C. Rotteveel, S.G.M. Frints, J.R. Hof, R.J. Stokroos, E.K. Vanhoutte, R.J.C. Admiraal, I. Feenstra, H. Kremer, H.P.M. Kunst, R.J.E. Pennings, H.G. Yntema, A.J. van Essen, R.H. Free, and J.S. Klein-Wassink

Web Resources

Alamut Visual, http://www.interactive-biosoftware.com/alamut- visual/

BioGRID, https://thebiogrid.org

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

Genome Diagnostics Radboudumc, https://www.radboudumc.nl/en/patientenzorg/onderzoeken/exome-sequencing-diagnostics/exomepanelspreviousversions/hearing-impairment

GnomAD Browser, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

Hereditary Hearing Loss, http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/

HomozygosityMapper, http://www.homozygositymapper.org/

Marshfield Genetic Maps, http://research.marshfieldclinic.org/genetics/GeneticResearch/compMaps.asp

Mutation Taster, http://www.mutationtaster.org/

Ocular Tissue Database, https://genome.uiowa.edu/otdb/

Oligo Primer Analysis Software, http://www.oligo.net/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

OMIM Phenotypic Series, http://www.omim.org/phenotypicSeriesTitle/all

Primer3Plus, http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi

STRING, https://string-db.org

UCSC Genome Browser, https://genome.ucsc.edu

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Sommen M., Schrauwen I., Vandeweyer G., Boeckx N., Corneveaux J.J., van den Ende J., Boudewyns A., De Leenheer E., Janssens S., Claes K. DNA diagnostics of hereditary hearing loss: A targeted resequencing approach combined with a mutation classification system. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:812–819. doi: 10.1002/humu.22999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan D., Tekin D., Bademci G., Foster J., 2nd, Cengiz F.B., Kannan-Sundhari A., Guo S., Mittal R., Zou B., Grati M. Spectrum of DNA variants for non-syndromic deafness in a large cohort from multiple continents. Hum. Genet. 2016;135:953–961. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1697-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloan-Heggen C.M., Bierer A.O., Shearer A.E., Kolbe D.L., Nishimura C.J., Frees K.L., Ephraim S.S., Shibata S.B., Booth K.T., Campbell C.A. Comprehensive genetic testing in the clinical evaluation of 1119 patients with hearing loss. Hum. Genet. 2016;135:441–450. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1648-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shearer A.E., Black-Ziegelbein E.A., Hildebrand M.S., Eppsteiner R.W., Ravi H., Joshi S., Guiffre A.C., Sloan C.M., Happe S., Howard S.D. Advancing genetic testing for deafness with genomic technology. J. Med. Genet. 2013;50:627–634. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atik T., Onay H., Aykut A., Bademci G., Kirazli T., Tekin M., Ozkinay F. Comprehensive analysis of deafness genes in families with autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0142154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zazo Seco C., Wesdorp M., Feenstra I., Pfundt R., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., Lelieveld S.H., Castelein S., Gilissen C., de Wijs I.J., Admiraal R.J. The diagnostic yield of whole-exome sequencing targeting a gene panel for hearing impairment in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:308–314. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zazo Seco C., Serrão de Castro L., van Nierop J.W., Morín M., Jhangiani S., Verver E.J., Schraders M., Maiwald N., Wesdorp M., Venselaar H., Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics Allelic mutations of KITLG, encoding KIT ligand, cause asymmetric and unilateral hearing loss and Waardenburg syndrome type 2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:647–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zazo Seco C., Castells-Nobau A., Joo S.H., Schraders M., Foo J.N., van der Voet M., Velan S.S., Nijhof B., Oostrik J., de Vrieze E. A homozygous FITM2 mutation causes a deafness-dystonia syndrome with motor regression and signs of ichthyosis and sensory neuropathy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017;10:105–118. doi: 10.1242/dmm.026476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garabatos N., Blanco J., Fandos C., Lopez E., Santamaria P., Ruiz A., Perez-Vidakovics M.L., Benveniste P., Galkin O., Zuñiga-Pflucker J.C., Serra P. A monoclonal antibody against the extracellular domain of mouse and human epithelial V-like antigen 1 reveals a restricted expression pattern among CD4- CD8- thymocytes. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2014;33:305–311. doi: 10.1089/mab.2014.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzoli M., Van Camp G., Newton V., Giarbini N., Declau F., Parving A. Recommendations for the description of genetic and audiological data for families with nonsyndromic hereditary hearing impairment. Audiol. Med. 2003;1:148–150. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huygen P.L.M., Pennings R.J.E., Cremers C.W.R.J. Characterizing and distinguishing progressive phenotypes in nonsyndromic autosomal dominant hearing impairment. Audiol. Med. 2003;1:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosman A.J., Smoorenburg G.F. Intelligibility of Dutch CVC syllables and sentences for listeners with normal hearing and with three types of hearing impairment. Audiology. 1995;34:260–284. doi: 10.3109/00206099509071918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallis Y., Payne S., McAnulty C., Bodmer D., Sistermans E., Robertson K., Moore D., Abbs S., Deans Z., Devereau A. ACGS and VGKL; 2013. Practice guidelines for the evaluation of pathogenicity and the reporting of sequence variants in clinical molecular genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seelow D., Schuelke M., Hildebrandt F., Nürnberg P. HomozygosityMapper—An interactive approach to homozygosity mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W593–W599. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfundt R., Del Rosario M., Vissers L.E.L.M., Kwint M.P., Janssen I.M., de Leeuw N., Yntema H.G., Nelen M.R., Lugtenberg D., Kamsteeg E.J. Detection of clinically relevant copy-number variants by exome sequencing in a large cohort of genetic disorders. Genet. Med. 2017;19:667–675. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krumm N., Sudmant P.H., Ko A., O’Roak B.J., Malig M., Coe B.P., NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, Quinlan A.R., Nickerson D.A., Eichler E.E. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luijendijk M.W., van de Pol T.J., van Duijnhoven G., den Hollander A.I., ten Caat J., van Limpt V., Brunner H.G., Kremer H., Cremers F.P. Cloning, characterization, and mRNA expression analysis of novel human fetal cochlear cDNAs. Genomics. 2003;82:480–490. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cediel R., Riquelme R., Contreras J., Díaz A., Varela-Nieto I. Sensorineural hearing loss in insulin-like growth factor I-null mice: A new model of human deafness. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:587–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murillo-Cuesta S., Rodríguez-de la Rosa L., Contreras J., Celaya A.M., Camarero G., Rivera T., Varela-Nieto I. Transforming growth factor β1 inhibition protects from noise-induced hearing loss. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:32. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skvorak A.B., Weng Z., Yee A.J., Robertson N.G., Morton C.C. Human cochlear expressed sequence tags provide insight into cochlear gene expression and identify candidate genes for deafness. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:439–452. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrauwen I., Hasin-Brumshtein Y., Corneveaux J.J., Ohmen J., White C., Allen A.N., Lusis A.J., Van Camp G., Huentelman M.J., Friedman R.A. A comprehensive catalogue of the coding and non-coding transcripts of the human inner ear. Hear. Res. 2016;333:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodoğlugil U., Mahley R.W. Turkish population structure and genetic ancestry reveal relatedness among Eurasian populations. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2012;76:128–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brownell W.E. Outer hair cell electromotility and otoacoustic emissions. Ear Hear. 1990;11:82–92. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199004000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su Y., Brooks D.G., Li L., Lepercq J., Trofatter J.A., Ravetch J.V., Lebo R.V. Myelin protein zero gene mutated in Charcot-Marie-tooth type 1B patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10856–10860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastaglia F.L., Nowak K.J., Stell R., Phillips B.A., Edmondston J.E., Dorosz S.M., Wilton S.D., Hallmayer J., Kakulas B.A., Laing N.G. Novel mutation in the myelin protein zero gene in a family with intermediate hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1999;67:174–179. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marrosu M.G., Vaccargiu S., Marrosu G., Vannelli A., Cianchetti C., Muntoni F. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 associated with mutation of the myelin protein zero gene. Neurology. 1998;50:1397–1401. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapon F., Latour P., Diraison P., Schaeffer S., Vandenberghe A. Axonal phenotype of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease associated with a mutation in the myelin protein zero gene. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1999;66:779–782. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.6.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayasaka K., Himoro M., Sawaishi Y., Nanao K., Takahashi T., Takada G., Nicholson G.A., Ouvrier R.A., Tachi N. De novo mutation of the myelin P0 gene in Dejerine-Sottas disease (hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy type III) Nat. Genet. 1993;5:266–268. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warner L.E., Hilz M.J., Appel S.H., Killian J.M., Kolodry E.H., Karpati G., Carpenter S., Watters G.V., Wheeler C., Witt D. Clinical phenotypes of different MPZ (P0) mutations may include Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1B, Dejerine-Sottas, and congenital hypomyelination. Neuron. 1996;17:451–460. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Planté-Bordeneuve V., Guiochon-Mantel A., Lacroix C., Lapresle J., Said G. The Roussy-Lévy family: From the original description to the gene. Ann. Neurol. 1999;46:770–773. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199911)46:5<770::aid-ana13>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guttinger M., Sutti F., Panigada M., Porcellini S., Merati B., Mariani M., Teesalu T., Consalez G.G., Grassi F. Epithelial V-like antigen (EVA), a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, expressed in embryonic epithelia with a potential role as homotypic adhesion molecule in thymus histogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:1061–1071. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeMonte L., Porcellini S., Tafi E., Sheridan J., Gordon J., Depreter M., Blair N., Panigada M., Sanvito F., Merati B. EVA regulates thymic stromal organisation and early thymocyte development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;356:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iacovelli S., Iosue I., Di Cesare S., Guttinger M. Lymphoid EVA1 expression is required for DN1-DN3 thymocytes transition. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner A.H., Anand V.N., Wang W.H., Chatterton J.E., Sun D., Shepard A.R., Jacobson N., Pang I.H., Deluca A.P., Casavant T.L. Exon-level expression profiling of ocular tissues. Exp. Eye Res. 2013;111:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuentes-Santamaría V., Alvarado J.C., Rodríguez-de la Rosa L., Murillo-Cuesta S., Contreras J., Juiz J.M., Varela-Nieto I. IGF-1 deficiency causes atrophic changes associated with upregulation of VGluT1 and downregulation of MEF2 transcription factors in the mouse cochlear nuclei. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016;221:709–734. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0934-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann Z.F., Kelley M.W. Development of tonotopy in the auditory periphery. Hear. Res. 2011;276:2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alasti F., Sanati M.H., Behrouzifard A.H., Sadeghi A., de Brouwer A.P., Kremer H., Smith R.J., Van Camp G. A novel TECTA mutation confirms the recognizable phenotype among autosomal recessive hearing impairment families. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behlouli A., Bonnet C., Abdi S., Hasbellaoui M., Boudjenah F., Hardelin J.P., Louha M., Makrelouf M., Ammar-Khodja F., Zenati A., Petit C. A novel biallelic splice site mutation of TECTA causes moderate to severe hearing impairment in an Algerian family. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;87:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinodoz M., Royer-Bertrand B., Cisarova K., Di Gioia S.A., Superti-Furga A., Rivolta C. DOMINO: Using machine learning to predict genes associated with dominant disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan A., Dallos P. Effect of absence of cochlear outer hair cells on behavioural auditory threshold. Nature. 1975;253:44–46. doi: 10.1038/253044a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liberman M.C., Gao J., He D.Z., Wu X., Jia S., Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorn P.A., Piskorski P., Gorga M.P., Neely S.T., Keefe D.H. Predicting audiometric status from distortion product otoacoustic emissions using multivariate analyses. Ear Hear. 1999;20:149–163. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199904000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoben R., Easow G., Pevzner S., Parker M.A. Outer hair cell and auditory nerve function in speech recognition in quiet and in background noise. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:157. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bombardelli L., Cavallaro U. Immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecules: Novel signaling players in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010;42:590–594. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rougon G., Hobert O. New insights into the diversity and function of neuronal immunoglobulin superfamily molecules. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;26:207–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramena G., Yin Y., Yu Y., Walia V., Elble R.C. CLCA2 interactor EVA1 is required for mammary epithelial cell differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teesalu T., Grassi F., Guttinger M. Expression pattern of the epithelial v-like antigen (Eva) transcript suggests a possible role in placental morphogenesis. Dev. Genet. 1998;23:317–323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)23:4<317::AID-DVG6>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chatterjee G., Carrithers L.M., Carrithers M.D. Epithelial V-like antigen regulates permeability of the blood-CSF barrier. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;372:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wojcik E., Carrithers L.M., Carrithers M.D. Characterization of epithelial V-like antigen in human choroid plexus epithelial cells: Potential role in CNS immune surveillance. Neurosci. Lett. 2011;495:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakata H., Wakayama T., Adthapanyawanich K., Nishiuchi T., Murakami Y., Takai Y., Iseki S. Compensatory upregulation of myelin protein zero-like 2 expression in spermatogenic cells in cell adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2012;45:47–56. doi: 10.1267/ahc.11057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohtsu N., Nakatani Y., Yamashita D., Ohue S., Ohnishi T., Kondo T. Eva1 maintains the stem-like character of glioblastoma-initiating cells by activating the noncanonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2016;76:171–181. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright E., Rahgozar K., Hallworth N., Lanker S., Carrithers M.D. Epithelial V-like antigen mediates efficacy of anti-alpha4 integrin treatment in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schraders M., Haas S.A., Weegerink N.J., Oostrik J., Hu H., Hoefsloot L.H., Kannan S., Huygen P.L., Pennings R.J., Admiraal R.J. Next-generation sequencing identifies mutations of SMPX, which encodes the small muscle protein, X-linked, as a cause of progressive hearing impairment. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:628–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitlon D.S. E-cadherin in the mature and developing organ of Corti of the mouse. J. Neurocytol. 1993;22:1030–1038. doi: 10.1007/BF01235747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simonneau L., Gallego M., Pujol R. Comparative expression patterns of T-, N-, E-cadherins, beta-catenin, and polysialic acid neural cell adhesion molecule in rat cochlea during development: Implications for the nature of Kölliker’s organ. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;459:113–126. doi: 10.1002/cne.10604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakano Y., Kim S.H., Kim H.M., Sanneman J.D., Zhang Y., Smith R.J., Marcus D.C., Wangemann P., Nessler R.A., Bánfi B. A claudin-9-based ion permeability barrier is essential for hearing. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ben-Yosef T., Belyantseva I.A., Saunders T.L., Hughes E.D., Kawamoto K., Van Itallie C.M., Beyer L.A., Halsey K., Gardner D.J., Wilcox E.R. Claudin 14 knockout mice, a model for autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29, are deaf due to cochlear hair cell degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2049–2061. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitajiri S., Katsuno T., Sasaki H., Ito J., Furuse M., Tsukita S. Deafness in occludin-deficient mice with dislocation of tricellulin and progressive apoptosis of the hair cells. Biol. Open. 2014;3:759–766. doi: 10.1242/bio.20147799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamitani T., Sakaguchi H., Tamura A., Miyashita T., Yamazaki Y., Tokumasu R., Inamoto R., Matsubara A., Mori N., Hisa Y., Tsukita S. Deletion of tricellulin causes progressive hearing loss associated with degeneration of cochlear hair cells. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18402. doi: 10.1038/srep18402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riazuddin S., Ahmed Z.M., Fanning A.S., Lagziel A., Kitajiri S., Ramzan K., Khan S.N., Chattaraj P., Friedman P.L., Anderson J.M. Tricellulin is a tight-junction protein necessary for hearing. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:1040–1051. doi: 10.1086/510022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilcox E.R., Burton Q.L., Naz S., Riazuddin S., Smith T.N., Ploplis B., Belyantseva I., Ben-Yosef T., Liburd N.A., Morell R.J. Mutations in the gene encoding tight junction claudin-14 cause autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29. Cell. 2001;104:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Togashi H., Kominami K., Waseda M., Komura H., Miyoshi J., Takeichi M., Takai Y. Nectins establish a checkerboard-like cellular pattern in the auditory epithelium. Science. 2011;333:1144–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.1208467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scheffer D.I., Shen J., Corey D.P., Chen Z.Y. Gene expression by mouse inner ear hair cells during development. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:6366–6380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5126-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van der Ploeg C.P., Uilenburg N.N., Kauffman-de Boer M.A., Oudesluys-Murphy A.M., Verkerk P.H. Newborn hearing screening in youth health care in the Netherlands: National results of implementation and follow-up. Int. J. Audiol. 2012;51:584–590. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.684402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parsa A., Webster P., Kalinec F. Deiters cells tread a narrow path—The Deiters cells-basilar membrane junction. Hear. Res. 2012;290:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.González-Mariscal L., Betanzos A., Avila-Flores A. MAGUK proteins: Structure and role in the tight junction. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;11:315–324. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huttlin E.L., Ting L., Bruckner R.J., Gebreab F., Gygi M.P., Szpyt J., Tam S., Zarraga G., Colby G., Baltier K. The BioPlex Network: A systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell. 2015;162:425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tamura A., Matsunobu T., Tamura R., Kawauchi S., Sato S., Shiotani A. Photobiomodulation rescues the cochlea from noise-induced hearing loss via upregulating nuclear factor κB expression in rats. Brain Res. 2016;1646:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dinh C.T., Bas E., Chan S.S., Dinh J.N., Vu L., Van De Water T.R. Dexamethasone treatment of tumor necrosis factor-alpha challenged organ of Corti explants activates nuclear factor kappa B signaling that induces changes in gene expression that favor hair cell survival. Neuroscience. 2011;188:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.