Abstract

Objective

To compare visual and refractive outcomes between self-refracting spectacles (Adaptive Eye-care, Ltd, Oxford, UK), noncycloplegic autorefraction, and cycloplegic subjective refraction.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Participants

Chinese school-children aged 12 to 17 years.

Methods

Children with uncorrected visual acuity ≤6/12 in either eye underwent measurement of the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution visual acuity, habitual correction, self-refraction without cycloplegia, autorefraction with and without cycloplegia, and subjective refraction with cycloplegia.

Main Outcome Measures

Proportion of children achieving corrected visual acuity ≥6/7.5 with each modality; difference in spherical equivalent refractive error between each of the modalities and cycloplegic subjective refractive error.

Results

Among 556 eligible children of consenting parents, 554 (99.6%) completed self-refraction (mean age, 13.8 years; 59.7% girls; 54.0% currently wearing glasses). The proportion of children with visual acuity ≥6/7.5 in the better eye with habitual correction, self-refraction, noncycloplegic autorefraction, and cycloplegic subjective refraction were 34.8%, 92.4%, 99.5% and 99.8%, respectively (self-refraction versus cycloplegic subjective refraction, P<0.001). The mean difference between cycloplegic subjective refraction and noncycloplegic autorefraction (which was more myopic) was significant (−0.328 diopter [D]; Wilcoxon signed-rank test P<0.001), whereas cycloplegic subjective refraction and self-refraction did not differ significantly (−0.009 D; Wilcoxon signed-rank test P = 0.33). Spherical equivalent differed by ≥1.0 D in either direction from cycloplegic subjective refraction more frequently among right eyes for self-refraction (11.2%) than noncycloplegic autorefraction (6.0%; P = 0.002). Self-refraction power that differed by ≥1.0 D from cycloplegic subjective refractive error (11.2%) was significantly associated with presenting without spectacles (P = 0.011) and with greater absolute power of both spherical (P = 0.025) and cylindrical (P = 0.022) refractive error.

Conclusions

Self-refraction seems to be less prone to accommodative inaccuracy than noncycloplegic autorefraction, another modality appropriate for use in areas where access to eye care providers is limited. Visual results seem to be comparable. Greater cylindrical power is associated with less accurate results; the adjustable glasses used in this study cannot correct astigmatism. Further studies of the practical applications of this modality are warranted.

Financial Disclosure(s)

Proprietary or commercial disclosure may be found after the references.

Vision impairment owing to refractive error is eminently correctable, yet it represents the second most common cause of treatable blindness in the world after cataract.1,2 The World Health Organization recently produced a series of projections identifying uncorrected refractive error as 1 of the 10 global health issues that will most severely affect productivity by 2030.3 The treatment of uncorrected refractive error is therefore a priority of VISION 2020, a joint initiative of the World Health Organization and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness.

The principal barrier to the provision of corrective eye-wear to people in low and middle income countries remains that of limited access to eye care providers. Although there is 1 eye care professional for every 6700 people in the United Kingdom,4 in parts of Africa the ratio is closer to 1:1 000 000.5,6 Whereas 70% of those living in the United Kingdom own glasses or contact lenses,7 up to 94% of those requiring glasses in sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to corrective eyewear.8

School-going children represent a particularly vulnerable group among those with uncorrected refractive error. Traditional classroom-based education is visually demanding and the inability to see clearly may have a dramatic impact on a child’s learning capability, educational potential, and career prospects. Consistent with this hypothesis, increasing myopic refractive error was strongly associated with worse self-reported visual function in a large study of school-age children in rural China,9 and correction of even modest amounts of refractive error led to significant improvements in all domains of visual function in another study of similar-aged children in rural Mexico.10 The Refractive Error Study in Children investigations, conducted at selected sites in Asia, Africa, and South America, suggest that ≥10% of children in the developing world could benefit from refractive correction,11–19 with the proportion significantly greater than this in some parts of Asia.20 There is also evidence that the prevalence of myopia may be increasing in many areas.21–24

How then can visual acuity correction be provided to school-going children in regions of the world with limited access to eye care providers? One approach to the delivery of refractive correction in such areas involves training teachers to conduct vision screening in the school setting.25–29 Such school-based models of visual acuity assessment are attractive in that they offer access to children in the care of a skilled workforce with ties to the local community. However, by itself, teacher vision screening addresses the problem of detection, but not correction, of refractive error.

A novel approach to the problem of correcting refractive error where access to eye care providers is limited involves the use of adjustable eyeglasses. These eyeglasses allow the user to change the power of each lens independently to achieve optimal visual acuity through the process of self-refraction. There are currently few published data on the accuracy and usability of such glasses,30–32 and no information of which we are aware on their use in children.

The purpose of the Child Self-Refraction Study is to compare the refractive power and visual acuity obtained with self-refraction among secondary school children in the school setting with results from 2 other refractive modalities: cycloplegic subjective refraction by trained eye care providers and noncycloplegic autorefraction. The latter is an approach likely to be used in settings where there is limited access to specialists trained in subjective refraction.

Methods

The protocol of the Child Self-Refraction Study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center and the University of Oxford; informed written consent was obtained from ≥1 parent of all participants, and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed throughout.

Participants

Two classes of approximately 45 children each were selected at random from Junior High School years 1 and 2 (ages approximately 13–15) at 6 schools in urban Guangzhou previously scheduled to undergo routine vision screening. All children with unaided visual acuity ≤6/12 in 1 or both eyes were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included keratoconus, amblyopia, and other systemic or ocular conditions that might prevent achieving corrected visual acuity of ≥6/7.5 in both eyes with subjective refraction. Sample size calculations had shown that 450 subjects would provide an estimate of agreement between the 2 methods of refraction lying within 20% of the true value with 95% confidence. This sample size was increased by 20% to account for classroom clustering effects, resulting in 540 subjects to be recruited; under an assumption that 50% of children would have no visual impairment, 1080 children were examined.

Visual Acuity Measurement

Measurement of distance visual acuity with and without existing corrective lenses (if worn) was carried out at 4 m with 1 of 3 back-illuminated Tumbling E logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution charts (2305, 2305A, 2305B, Precision Vision, La Salle, IL) in an area of each school with luminance in the range of 500 to 750 lux (Testo 540, Testo AG, Lenzkirch, Germany). Starting on the top (6/60) line, testing proceeded sequentially to the lowest line on which the orientation of ≥4 of 5 optotypes was correctly identified with first the left and then the right eye occluded. Study personnel directed subjects to maintain a neutral head position and avoid narrowing of the palpebral fissure in the tested eye. Subjects failing to read the 6/60 line were to be tested using the identical protocol at 1 m, although in practice no such children were encountered.

Examination Procedures

After measurement of visual acuity, all subjects with uncorrected visual acuity ≤6/12 in ≥1 eye underwent an examination consisting of the following elements.

Lensometry

Lensometry (CL100 automatic lensometer with printer, Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was performed to determine the power of the subject’s current eyeglass prescription, if worn, rounded to the nearest 0.25 diopter (D) for sphere and cylinder values and 1 degree for axis.

Self-refraction

The self-refraction spectacles used in this study (Adspecs, Adaptive Eyecare, Ltd, Oxford, UK) contain 2 fluid-filled lenses, each consisting of 2 membranes 23 m thick sealed at a circular perimeter of diameter 42 mm and secured by a frame (Fig 1; available online at http://aaojournal.org). The front face of each deformable lens is protected by a rigid plastic cover. The volume enclosed by the membranes is filled with a liquid of refractive index 1.579. The optical power of the resulting lens is determined by the curvature of its surfaces, and this is controlled by varying the volume of liquid in the lens. Two user-controlled pumps marked with a scale in diopters and capable of withdrawing or returning fluid to the 2 lens chambers independently are attached to the sides of the spectacle frame. Spherical refractive power ranging from −6.00 to +6.00 D is obtainable, although no cylindrical correction is possible. The lens may be sealed and the adjustment mechanism removed after the desired power is obtained.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the adjustable glasses (Adaptive Eyecare Ltd., Oxford, UK), with the adjustment knobs indicated by the open arrow and the diopter scale on the user-controlled pump indicated by the solid arrow.

Self-refraction was monitored by the teacher of each participating class. All teachers participated in a 1- to 2-hour training workshop where the protocol was reviewed and practiced. After inspection of the device to ascertain that the pumps were properly attached and aligned with zero on each side, the teacher instructed the child to place the glasses on the face and cover the left eye with the left hand. Visual acuity was measured for the right eye using the described protocol and with the spectacles set to zero power. Children were told to turn the dial backward (creating a minus power lens) slowly until the letters on the vision chart became as clear as possible, and then to make small adjustments in either direction to refine the visual acuity, which was measured again. Finally, subjects were directed to turn the dial forward (reducing minus power) until the smallest visible line began to blur slightly. The visual acuity was measured again and, if there was no decrease from the previous step, it was accepted as the final value. In the event that the visual acuity did not improve over unaided acuity, teachers would check again that the plunger was aligned with zero and also that the lens surfaces were clean. If visual acuity still did not improve, the protocol was repeated again with the plunger aligned initially at +6.00 D instead of at zero. The same steps were repeated for the left eye. The power of each lens on the self-refracting spectacles was measured using the lensometer as described.

The entire measurement protocol was repeated, and the visual acuity and lens powers for the right and left eye on the second trial recorded and utilized in all subsequent analyses. Measurement of visual acuity after self-refraction was carried out with a chart different from that used during assessment of unaided distance visual acuity.

Autorefraction

Autorefraction (KR8800, Topcon Corp.) was carried out before cycloplegia and according to procedures in the manufacturer’s instruction manual, with the vertex distance at 12 mm and measurement step size of 0.25 D for sphere and cylinder power. Five measurements were made and the mean value from the machine printout recorded as the final outcome in each eye. Visual acuity was then measured as outlined above through trial lenses with the indicated power and using a tumbling E logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution chart with different layout. A model eye provided by the manufacturer was used to monitor the calibration of the instrument at the beginning and end of each day.

Cycloplegic Subjective Refraction

Cycloplegia was accomplished for all subjects by means of 2 drops of 1% cyclopentalate administered 5 minutes apart in each eye. A third drop was administered if the pupillary light reflex was still present 15 minutes later. Absence of the light reflex was considered evidence of adequate dilation. After cycloplegic autorefraction, subjective refraction was performed by an optometrist masked to the results of self-refraction and noncycloplegic autorefraction. The starting point was taken as the mean cycloplegic autorefraction result and the endpoint as the least myopic spherical power providing best acuity. Visual acuity was measured with the tumbling E logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution chart used during the unaided distance visual acuity assessment.

Media and Fundus Examination

This was carried out by an ophthalmologist using a direct and indirect ophthalmoscope after pupillary dilation as described. Subjects with any abnormality of the anterior segment, vitreous, or fundus were referred for care as needed. Although children with disqualifying abnormalities (as outlined) were by protocol required to be removed from subsequent data analysis, no such subjects were detected.

Statistical Methods

Study data were entered on examination forms, which were reviewed for accuracy and missing values in the field. Data entry and computerized range and consistency checks were conducted at the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center.

Visual acuity in better- and worse-seeing eyes was tabulated without correction, with habitual (presenting) correction, with correction based on self-refraction, with noncycloplegic autorefraction, and with cycloplegic subjective refraction. The 2-sample test of proportion was used to compare the proportion of children reaching visual acuity ≥6/7.5 in the better-seeing eye with cycloplegic subjective refraction versus habitual, self-refraction, and noncycloplegic autorefraction. Multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the association of age, gender, spectacle usage, and cycloplegic autorefraction sphere and cylinder with failure to achieve visual acuity ≥6/7.5 with self-refraction in the right eye among children with uncorrected visual acuity ≤6/12 in the right eye (remaining subjects entered the study on the basis of visual acuity ≤6/12 in the left eye only).

Refraction data were analyzed on the basis of spherical equivalent refractive error (sphere + ½ cylinder). Box plots were used for graphical representations of the distribution of spherical equivalent refractive error for the four measurement methods. The Wilcoxon test was used in testing equality between refraction methods. (The normality assumption of the t-test for paired samples, as tested with the Shapiro–Francia test, was not satisfied.) Differences between cycloplegic subjective refraction and the other 3 methods were calculated by subtracting the cycloplegic subjective value from the comparison value. Differences were graphically illustrated using Bland–Altman scatter diagrams plotting the difference between 2 methods against their mean, and with the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentile differences shown.

Multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the association of age, gender, spectacle use, and cycloplegic autorefraction sphere and cylinder with having self-refraction measurements in the right eye that differed by ≥1.00 D in the myopic or hyperopic direction from the spherical equivalent cycloplegic subjective refraction.

Analyses and statistical tests were performed using Stata Statistical Software, Release 9.06 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Confidence intervals (CI) and P-values (considered to be significant at the P≤0.05 level) in logistic regressions were calculated with adjustment for clustering effects associated with the class-based sampling.

Results

Among 1139 children undergoing vision screening, 581 (51.0%) had uncorrected visual acuity ≤6/12 in either eye, and were thus eligible to take part in the study. Twenty-five of these children did not consent to cycloplegia and another 2 were unable to complete self-refraction, leaving 554 participants in the study population. The 554 children were drawn from 24 classes in 6 schools. Only 1 child had an abnormality detected on dilated examination, namely myelinated optic disc fibers.

The age and gender distribution of the study population is shown in Table 1. The mean age for both boys and girls was 13.8 years. More than half (54.0%) of the participants were wearing spectacles at the time of examination, including 46.6% of boys and 58.9% of girls (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test,; P = 0.028).

Table 1.

Distribution of Age and Gender among Study Participants: Chinese Secondary School Children with Uncorrected Vision ≤6/12 in ≥1 Eye and Completing an Examination Consisting of Self-Refraction, Noncycloplegic Autorefraction, Cycloplegic Autorefraction, and Cycloplegic Subjective Refraction

| Age (yrs) | Boys, n (%) | Girls, n (%) | Both, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12–13* | 88 (39.5) | 114 (34.4) | 202 (36.5) |

| 14 | 96 (43.1) | 161 (48.6) | 257 (46.4) |

| 15–17† | 39 (17.5) | 56 (16.9) | 95 (17.2) |

| All | 223 (40.3) | 331 (59.7) | 554 (100.0) |

Includes 7 boys and 11 girls age 12 years.

Includes 4 boys and 6 girls age 16 years and 3 boys age 17 years.

Visual acuity in the better- and worse-seeing eyes with the different methods of correction is shown in Table 2. Without correction, median and mean visual acuity in the better-seeing eye were 0.25 (6/24) and 0.328 (roughly equivalent to 6/19), respectively. For the worse seeing-eye, median and mean uncorrected visual acuity were 0.20 (6/30) and 0.225 (between 6/24 and 6/30), respectively. With habitual correction, median and mean visual acuity in the better eye were 0.625 (6/9.5) and 0.597 (roughly 6/9.5), respectively.

Table 2.

Distribution of Visual Acuity (Given as Number and Percent of Children) without Correction, with Habitual Correction, with Self-Refraction, with Noncycloplegic Autorefraction, and with Cycloplegic Subjective Refraction among Study Participants (554 Children with Uncorrected Vision ≤6/12 in ≥1 Eye)

| Visual Acuity (n 554) Snellen (Decimal) | Without Correction

|

With Habitual Correction

|

Correction With Self-refraction

|

Correction with Noncycloplegic Autorefraction*

|

Correction with Cycloplegic Subjective Refraction

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Better Eye | Worse Eye | Better Eye | Worse Eye | Better Eye | Worse Eye | Better Eye | Worse Eye | Better Eye | Worse Eye | |

| 6/6 (1.00) | 20 (3.6) | 88 (15.9) | 31 (5.6) | 321 (57.9) | 202 (36.5) | 507 (91.5) | 436 (78.7) | 525 (94.8) | 500 (90.3) | |

| 6/7.5 (0.80) | 25 (4.5) | 105 (19.0) | 68 (12.3) | 191 (34.5) | 207 (39.2) | 39 (7.0) | 95 (17.2) | 28 (5.1) | 43 (7.8) | |

| 6/9.5 (0.625) | 36 (6.5) | 95 (17.2) | 55 (9.9) | 28 (5.1) | 86 (15.5) | 2 (0.36) | 8 (1.4) | 1 (0.18) | 7 (1.3) | |

| 6/12 (0.50) | 66 (11.9) | 40 (7.2) | 102 (18.4) | 96 (17.3) | 10 (1.8) | 32 (5.8) | 1 (0.18) | 6 (1.1) | ||

| 6/15 (0.40) | 65 (11.7) | 77 (13.9) | 59 (10.7) | 100 (18.1) | 1 (0.18) | 6 (1.1) | 1 (0.18) | 3 (0.54) | ||

| 6/19 (0.32) | 38 (6.9) | 63 (11.4) | 31 (5.6) | 74 (13.4) | 2 (0.36) | 5 (0.90) | 1 (0.18) | 1 (0.18) | ||

| 6/24 (0.25) | 63 (11.4) | 50 (9.0) | 31 (5.6) | 40 (7.2) | 1 (0.18) | 6 (1.1) | ||||

| 6/30 (0.20) | 55 (9.9) | 65 (11.7) | 20 (3.6) | 36 (6.5) | ||||||

| 6/38 (0.16) | 56 (10.1) | 64 (11.6) | 14 (2.5) | 28 (5.1) | 2 (0.36) | |||||

| 6/48 (0.125) | 51 (9.2) | 68 (12.3) | 6 (1.1) | 12 (2.2) | ||||||

| 6/60 (0.10) | 58 (10.5) | 94 (17.0) | 3 (0.54) | 14 (2.5) | ||||||

| < 6/60 (<0.10) | 21 (3.8) | 33 (6.0) | ||||||||

| Median visual acuity | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.625 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mean visual acuity | 0.328 | 0.225 | 0.597 | 0.462 | 0.898 | 0.814 | 0.984 | 0.949 | 0.989 | 0.975 |

Visual acuity associated with the noncycloplegic autorefraction measurement was unavailable for 5 children.

The proportion of children with visual acuity in the better-seeing eye ≥6/7.5 with habitual correction, self-refraction, noncycloplegic autorefraction, and cycloplegic subjective refraction were 34.8%, 92.4%, 99.5% and 99.8%, respectively (Table 2). This proportion differed significantly between habitual correction and cycloplegic subjective refraction (2-sample test of proportion; P<0.001), between self-refraction and cycloplegic subjective refraction (P<0.001), but not between noncycloplegic autorefraction and cycloplegic subjective refraction (P = 0.316). Among 524 children with uncorrected visual acuity ≤6/12 in the right eye, 83 (15.8%) failed to reach visual acuity of ≥6/7.5 with self-refraction. Twenty-one (25.9%) of these children had ≥1.00 D of astigmatism. In logistic regression models, predictors for failing to achieve this level of visual acuity included female gender (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.45; 95% CI, 1.31–4.61; P = 0.007), presenting without spectacles (OR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.68–5.75; P = 0.001), and greater absolute value of spherical (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.13–1.60, P = 0.002), and cylindrical (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.80–3.28; P<0.001) refractive error with cycloplegic autorefraction. Age was not associated with achieving good visual acuity in this model (P = 0.560).

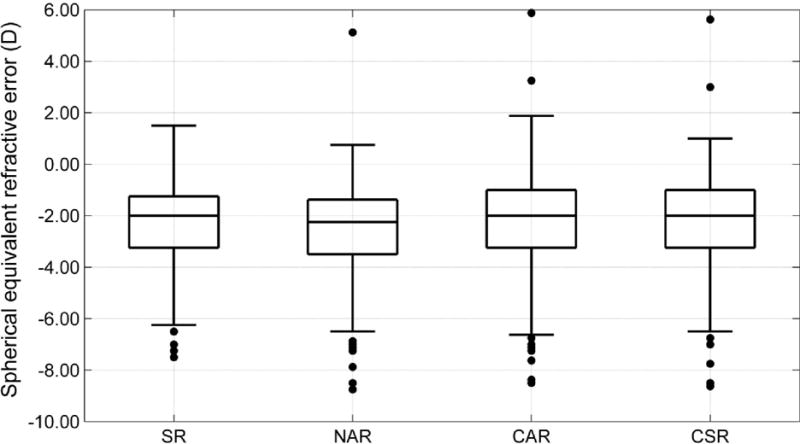

The distribution of spherical equivalent refractive error in right eyes is shown in Figure 2 (available online at http://aaojournal.org) for self-refraction, noncycloplegic autorefraction, cycloplegic autorefraction, and cycloplegic subjective refraction. Table 3 (available online at http://aaojournal.org) indicates the prevalence of astigmatism among study subjects based on cycloplegic autorefraction.

Figure 2.

Box plot representations of the distribution of spherical equivalent refractive error based on self-refraction (SR), non-cycloplegic auto-refraction (NAR), cycloplegic auto-refraction (CAR), and cycloplegic subjective refraction (CSR). Each box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile, the interquartile range, with the inside bar representing the median. Whiskers extend to the lower and upper extremes, defined as the 25th percentile minus 1.5 times the interquartile range and the 75th percentile plus 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Table 3.

Astigmatism based on cycloplegic auto-refraction in children with uncorrected visual acuity ≤ 6/12 in at least one eye.

| Astigmatism (diopters) | Right eves | Left eyes | Either eye |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No.(%) | No.(%) | |

| ≤ 0.50 | 436 (78.7) | 380 (68.6) | 345 (62.3) |

| 0.75 – 1.25 | 98 (17.7) | 137 (24.7) | 167 (30.1) |

| 1.50 – 1.75 | 8 (1.4) | 21 (3.8) | 23 (4.2) |

| ≥ 2.00 | 12 (2.17) | 16 (2.9) | 19 (3.4) |

| ALL | 554 (100.0) | 554 (100.0) | 554 (100.0) |

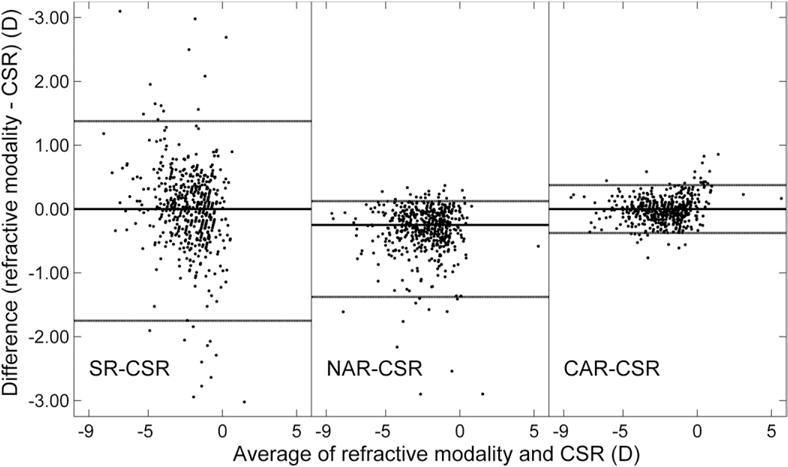

Bland–Altman plots are shown in Figure 3 comparing cycloplegic subjective refraction as a “gold standard” against each of the following: Self-refraction, noncycloplegic autorefraction, and cycloplegic autorefraction. The difference between cycloplegic subjective refraction and the more myopic noncycloplegic autorefraction in right eyes was significant (Wilcoxon signed-rank test; P<0.001), with a median difference of −0.25 D, and with 95% of the differences between −1.38 and +0.13 D. The difference between cycloplegic subjective refraction and cycloplegic autorefraction was also significant (P = 0.002), with a median difference of 0.00 D, and with 95% of the differences between −0.375 and +0.38 D. Cycloplegic subjective refraction and self-refraction did not differ (P = 0.330), with a median difference of 0.0 D, and with 95% of the differences between −1.75 and +1.375 D. (The distribution of differences was similar in left eyes.)

Figure 3.

Bland–Altman plots comparing cycloplegic subjective refractive error (CSR) and each of the following modalities: Self-refraction (SR), noncycloplegic autorefraction (NAR), and cycloplegic autorefraction (CAR). The horizontal lines represent, from top to bottom, the 97.5th percentile, the median and the 2.5th percentile, respectively. D = diopter.

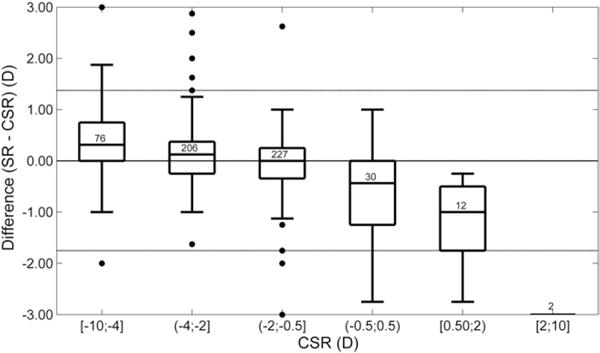

The difference between self-refraction and cycloplegic subjective refraction was more negative (indicative of more error in the hyperopic direction for self-refraction) among children with more hyperopic refractive error (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Box plot representation of the difference between self-refraction (SR) and cycloplegic subjective refraction (CSR) for different levels of cycloplegic subjective refractive error. D = diopter.

The 11.2% of right eyes with self-refraction power differing by ≥1.0 D in either a hyperopic or myopic direction from the cycloplegic subjective refraction value was significantly greater than the 6.0%, which so differed from the cycloplegic subjective value for noncycloplegic autorefraction (2-sample test of proportion; P = 0.002) and the 0.0% with cycloplegic autorefraction (P<0.001). In logistic regression modeling, having self-refraction power that differed by ≥1.0 D in the myopic or hyperopic direction from the spherical equivalent cycloplegic subjective refractive error was significantly associated with presenting without spectacles (adjusted OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.22–3.86; P = 0.011) and with both greater absolute power of spherical (OR, 1.29; 05% CI, 1.04–1.62; P = 0.025) and cylindrical (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.08–2.54; P = 0.022) refractive error. Neither age nor gender was associated with inaccuracy of self-refraction in the model (P = 0.585 and P = 0.269, respectively).

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to compare the validity of noncycloplegic self-refraction with 2 other refractive modalities: cycloplegic subjective refraction and noncycloplegic autorefraction. Cycloplegic subjective refraction was chosen to represent the gold standard in assessing refractive power. Noncycloplegic autorefraction was selected as the modality most likely to be used in parts of the world where access to eye care providers is limited, the setting in which self-refraction would be most relevant. Previous studies30–32 have suggested that refractive results and acuity comparable with those obtained by an optometrist were achievable with self-refraction by adults in several African countries and Nepal, but the current investigation is the first published report of which we are aware to assess performance among school-aged children.

The mean spherical equivalent for self-refraction did not differ from that for cycloplegic subjective refraction, whereas that for noncycloplegic autorefraction was approximately one third of a diopter more myopic. This suggests that the myopic shift, presumably owing to instrument accommodation, previously reported for noncycloplegic autorefraction in school-aged children33,34 may be less of an issue with self-refraction, as might be expected given the more distant target.

Some 11% of children had refractive values in the right eye with self-refraction that differed from cycloplegic subjective refraction by ≥1 diopter in the hyperopic or myopic direction, a degree of inaccuracy that might be expected to be symptomatic. This was significantly greater than the proportion of children experiencing a similar ≥1.00-D difference between noncycloplegic autorefraction and cycloplegic subjective refraction. The 95 percentile range of differences between noncycloplegic self-refraction and cycloplegic subjective refraction (between −1.75 and +1.375 D) was comparable with the 95% limits of agreement35,36 reported for cycloplegic autorefraction versus subjective refraction among children,37–40 ±0.67 D to ±1.72 D, and lower than reported limits of agreement comparing noncycloplegic autorefraction and subjective refraction among children,38,40–42 ±1.76 D to ±3.99 D.

Our regression model indicated that children with greater amounts of spherical and cylindrical refractive error were at greater risk for inaccurate self-refraction results. The latter is presumably because the self-refraction spectacles are incapable of correcting astigmatism, whereas the former might because the limits of correction with this device are ±6.00 D. Children not habitually wearing spectacles were also at greater risk for less accurate results with self-refraction. One possible explanation is that such children are more tolerant of imperfectly corrected visual acuity, and were thus less inclined to carefully adjust the self-refracting spectacles until optimal visual acuity and more accurate power had been achieved. If so, this might have implications for the use of this technology in areas where failure to wear refractive correction is even more common.

Although a comparison of the distribution of refractive error values obtained is a simple and objective way to compare refractive modalities, the range of visual acuities achieved is in many ways of greater significance programmatically. The proportion of children failing to achieve visual acuity ≥6/7.5 in the better eye with self-refraction (<10%) differed significantly from the proportion failing to achieve such visual acuity with cycloplegic subjective refraction. Regression models showed that, as with refractive power, higher spherical and cylindrical refractive error and failure to wear spectacles habitually were predictive of achieving poorer visual acuity with self-refraction. Girls were also at greater risk for poor visual results with self-refraction. This suggests that teachers should be instructed to spend more time explaining the technique to female students, particularly given the greater burden of refractive error reported for girls in China.20,21

Comparison of self-refraction to ready-made spectacles is relevant to program planners considering interventions in areas where refractive and optical services may be scarce. Anisometropia of ≥1.00 D by cycloplegic subjective refraction was present in 9.4% of participants in the current study. Such children might be expected to have poorer visual acuity in ≥1 eye, and potentially asthenopic symptoms, with ready-made spectacles of a single power in both eyes, but could in principle achieve optimal spherical equivalent power in each eye with self-refraction. A recent clinical trial in China43 has suggested that ready-made spectacles did not differ significantly from custom spectacles in acceptability to children, although 10% of potential subjects were excluded owing to anisometropia or astigmatism.

Our results suggest that self-refraction is capable of achieving refractive accuracy and visual acuity outcomes clinically comparable with, although by some measures significantly worse than, noncycloplegic autorefraction among urban Chinese secondary school children. Given the cost and maintenance issues associated with autorefractor use, and the risks, time required, potential for reduction in acceptance of services, and need for trained personnel involved in cycloplegia, these findings are of potential significance for children’s refractive programs in underserved areas. In addition to their use as a refractive device, self-refracting spectacles offer the potential to modify lens power, which may help to address the problem of outdated and inaccurate spectacles, which is common in some areas.12–19,44 In this latter respect, self-refracting spectacles offer a potential advantage over the Focometer, a self-adjusting focusable telescope reported previously to have accuracy similar to Adspecs in the measurement of spherical equivalent refractive error,32 but which is not appropriate for use in refractive correction. Self-refracting glasses also avoid the potential complexity of training involved in the use of streak retinoscopy,45 which also requires subjective refinement for optimum accuracy.46

Several issues remain to be clarified in the use of self-refraction, however. The current study did not assess the safety or long-term accuracy and acceptability of self-refracting spectacles for daily wear among children. Furthermore, the urban children and teachers participating in this investigation may not be representative of rural dwellers, who are the likely potential targets for self-refracting technology. Further studies of self-refracting spectacles in rural areas in China are now under way. Finally, results of the current study are applicable only to the particular self-refracting device tested. Other such devices are available that may perform differently; the authors are unaware of published data on the performance of other self-refracting technologies in children.

The results and implications of this study must be understood within the context of its other limitations as well. The sample of participating children was not population based; for this and the other reasons mentioned, these results may be extrapolated to other areas only with caution. It has been demonstrated that inaccuracies owing to accommodation without cycloplegia in school-aged children are greatest in hyperopes and least in myopes.32,33 The distribution of refractive errors in this urban Chinese cohort was heavily skewed toward myopic powers, which might have tended to reduce inaccuracies owing to accommodation during self-refraction without cycloplegia. The tendency toward more error in the myopic direction in self-refraction versus cycloplegic subjective refraction among children with hyperopia (Fig 4) may be evidence of this phenomenon. Finally, our protocol called for the various refractive modalities to be carried out in a predetermined order, rather than randomly. The possibility that fatigue may have affected the accuracy of noncycloplegic autorefraction and cycloplegic subjective refraction (which followed self-refraction in the protocol) cannot be excluded.

Despite its limitations, the current study is the first of which we are aware to provide evidence of the validity of self-refraction among children. The setting in China, a country with 1 of the highest burdens of uncorrected refractive error in the world, is highly relevant to the potential future use of this technology. Further research is needed to assess remaining issues regarding the practical application of this promising modality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Don Bundy, of the World Bank Human Development Network, and Julian Lambert of Adaptive Eyewear, Ltd., for early suggestions about the research included in this manuscript.

Financial Disclosure(s):

Graeme MacKenzie – employee – Adlens Ltd.

Joshua D. Silver – shareholder and director – Adaptive Eyecare Ltd.; shareholder – Adlens Ltd.

Funded by a subgrant to the Nuffield Laboratory of Ophthalmology (University of Oxford) from the Partnership for Child Development, (Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) under the World Bank’s FY2009 Development Grant Facility (DGF) Window 1. The self-refracting spectacles used in this study were provided free of charge by Adaptive Eyecare, Ltd.

References

- 1.Dandona R, Dandona L. Refractive error blindness. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:237–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:63–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathers C, Boerma JT, Fat DM. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Vol. 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; pp. 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Ophthalmic Services: Workforce Statistics for England and Wales. The Information Centre, Ophthalmic Statistic. 2007 Available at: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/goswf311206/General%20Ophthalmic%20Services%20Workforce%2031%20Dec%202006.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2010.

- 5.Mathenge W, Nkurikiye J, Limburg H, Kuper H. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in western Rwanda: blindness in a postconflict setting. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson AS. Optometry in Ethiopia. S Afr Optom. 2008;67:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajekal M, Primatesta P, Prior G, editors. Health Survey for England. 2nd. London: Stationary Office; 2001. Available at: http://www.archive2.official-documents.co.uk/document/deps/doh/survey01/hse01.htm. Accessed July 2, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM, et al. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1731–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Congdon NG, Wang Y, Song Y, et al. Visual disability, visual function and myopia among rural Chinese secondary school children: the Xichang Pediatric Refractive Error Study (X-PRES)–report 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2888–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteso P, Castanon A, Toledo S, et al. Correction of moderate myopia is associated with improvement in self-reported visual functioning among Mexican school-aged children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4949–54. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP, et al. Refractive Error Study in Children: sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:421–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maul E, Barroso S, Muñoz SR, et al. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:445–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R, et al. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:427–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Muñoz SR, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:436–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, et al. Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:615–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Ellwein LB, et al. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:623–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naidoo KS, Raghunandan A, Mashige KP, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3764–70. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He M, Zeng J, Liu Y, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern China. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:793–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He M, Huang W, Zheng Y, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in rural southern China. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin LL, Shih YF, Tsai CB, et al. Epidemiologic study of ocular refraction among schoolchildren in Taiwan in 1995. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:275–81. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CK, et al. Epidemiologic study of the prevalence and severity of myopia among schoolchildren in Taiwan in 2000. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:684–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saw SM, Wu HM, Seet B, et al. Academic achievement, close up work parameters, and myopia in Singapore military conscripts. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:855–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vitale S, Sperduto RD, Ferris FL., III Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971-1972 and 1999-2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1632–9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castanon Holguin AM, Congdon N, Patel N, et al. Factors associated with spectacle-wear compliance in school-aged Mexican children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:925–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciner EB, Dobson V, Schmidt PP, et al. A survey of vision screening policy of preschool children in the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43:445–57. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limburg H, Kansara HT, d’Souza S. Results of school eye screening of 54 million children in India–a five-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:310–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma A, Li L, Song Y, et al. Strategies to improve the accuracy of vision measurement by teachers in rural Chinese secondary schoolchildren: Xichang Pediatric Refractive Error Study (X-PRES) report no 6. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1434–40. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wedner SH, Ross DA, Balira R, et al. Prevalence of eye diseases in primary school children in a rural area of Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1291–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.11.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silver JD, Douali MG. How to use an adaptive optical approach to correct vision globally. Available at: http://research.opt.indiana.edu/Library/Mopane2003/SilverJ/Silver.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2010.

- 31.Douali MG, Silver JD. Self-optimised vision correction with adaptive spectacle lenses in developing countries. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:234–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2004.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith K, Weissberg E, Travison TG. Alternative methods of refraction: a comparison of three techniques. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87:e176–82. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181cf86d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao J, Mao J, Luo R, et al. Accuracy of noncycloplegic autorefraction in school-age children in China. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fotedar R, Rochtchina E, Morgan I, et al. Necessity of cycloplegia for assessing refractive error in 12-year-old children: a population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:307–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altman DG, Bland JM. Measurement in medicine: the analysis of method comparison studies. Statistician. 1983;32:307–17. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chat SW, Edwards MH. Clinical evaluation of the Shin-Nippon SQR-5000 autorefractor in children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2001;21:87–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choong YF, Chen AH, Goh PP. A comparison of autore-fraction and subjective refraction with and without cycloplegia in primary school children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harvey EM, Miller JM, Wagner LK, Dobson V. Reproducibility and accuracy of measurements with a hand held autorefractor in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:941–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.11.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wesemann W, Dick B. Accuracy and accommodation capability of a handheld autorefractor. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:62–70. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nayak BK, Ghose S, Singh JP. A comparison of cycloplegic and manifest refractions on the NR-1000F (an objective auto refractometer) Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:73–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schimitzek T, Wesemann W. Clinical evaluation of refraction using a handheld wavefront autorefractor in young and adult patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:1655–66. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng Y, Keay L, He M, et al. A randomized, clinical trial evaluating ready-made and custom spectacles delivered via a school-based screening program in China. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1839–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang M, Lv H, Gao Y, et al. Visual morbidity due to inaccurate spectacles among school children in rural China: the See Well to Learn Well Project, report 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2011–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donovan L, Brian G, du Toit R. A device to aid the teaching of retinoscopy in low-resource countries [letter] Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:294. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.121699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Academy of Ophthalmology Refractive Management/Intervention Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern Refractive Errors and Refractive Surgery. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2007. p. 8. Available at: http://one.aao.org/CE/PracticeGuidelines/PPP.aspx. Accessed March 16, 2010. [Google Scholar]