Abstract

Background

Gut microbiota contributes to intestinal and immune homeostasis through host-microbiota interactions. Distribution of the gut microbiota differs according to the location in the gastrointestinal tract. Although the microbiota properties change with age, evidence for the regional difference of gut microbiota has been restricted to the young. The aim of this study is to compare the gut microbiota between terminal ileum and cecum of old rats.

Methods

We analyzed gut microbiome of luminal contents from ileum and cecum of 74-week-old and 2-year-old rats (corresponding to 60-year and 80-year-old of human age) by metagenome sequencing of 16S rRNA.

Results

Inter-individual variation (beta diversity) of microbiota was higher in ileum than in cecum. Conversely, alpha diversity of microbiota composition was higher in cecum than in ileum. Lactobacillaceae were more abundant in ileum compared to cecum while Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae were more enriched in cecum. The proportions of Deltaproteobacteria were increased in cecal microbiota of 2-year-old rats compared to 74-week-old rats.

Conclusions

Major regional distinctions of microbiota between ileum and cecum of old rats appear consistent with those of young rats. Age-related alterations of gut microbiota in old rats seem to occur in minor compositions.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal microbiome, Ileum, Cecum, Aging, Rats

INTRODUCTION

Gut microbiota plays an important role in maintaining host health. Major functions of the commensal microbiota include protection against epithelial damage,1 promotion of intestinal angiogenesis,2 and metabolism of nutrients and food components.3,4 The gut microbiota distribute differently according to intestinal locations.5 The bacterial load increases from stomach to colon. The number of bacteria is 101 to 103 cells/g in the stomach and duodenum, and 104 to 107 cells/g in the jejunum and ileum, and 1011 to 1012 cells/g in the colon.6,7 Generally, bacterial growth is limited in stomach for the gastric acidity and oxygen content. In duodenum, the gastric acid is neutralized, and bile acids become a regulator of microbial growth. Decrease of oxygen, formation of mucous layer, and digestion of starches into monosaccharides and disaccharides in small intestine result in enrichment of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes including Lactobacillales with low microbial diversity.8 In colon, polysaccharides that are not digested by host promote the colonization of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes including Clostridiales.8

Profiles of bacterial community have been established in young mice and rats,9,10 as well as in human.6 Regional differences of microbiota along the gastrointestinal tract have been reported in several other species such as piglets and ruminants.11,12 These studies suggested that location-specific shift of gut microbiota may influence development of the mucosal immune system. However, to our knowledge, it has not been reported about the age-related alterations of regional differences of gut microbiota in the old age.

Lifespan has been extended during several decades. Therefore, maintenance of proper populations of microbiota is considered to be important to improve elderly health. Gut microbiota of the elderly differs from that of the younger adults, with a greater abundance of Bacteroides and different proportions of Clostridium groups.13 Gut microbiota in the elderly change according to age and is affected by environmental factors such as diet and residence.14,15 In extreme aging, proteolytic bacteria increase and saccharolytic bacteria decrease, which are related with sarcopenia and longevity.16 The age-related change of gut microbiota is associated with immunosenescence, which promote the elderly intestines to be in a pro-inflammatory status through continuous NF-κB-mediated inflammation and deprivation of naïve CD4+ T cells.17,18

Gut microbiota is associated with the gastrointestinal cancer development. Gastric microbiota of gastric carcinoma patients is distinct from that of chronic gastritis patients, showing dysbiotic properties, such as decreased microbial diversity and increased genotoxic potential.19 Intestinal microbiota is linked to the colorectal cancer.20 The promotion of colorectal cancer by gut microbiota has been demonstrated by experimental evidence. Thus, gavage of stools from patients with colorectal cancer induced colorectal carcinogenesis in germ-free mice and conventional mice given azoxymethane.21

The laboratory rat is a long-used animal model in biomedical research. Since it is difficult to control experimental conditions and collect specimens from diverse anatomical sites in human subjects, it is necessary to understand the microbiota of laboratory animal models to establish further knowledge about the human gut microbiota. Among the laboratory rats, Fisher-344 rat has been widely used for aging studies due to its appropriate lifespan.22,23 In this study, we used 74-week-old and 2-year-old rats that correspond to 60-year-old and 80-year-old of human age, respectively, to investigate the gut microbiota in old rats.

From this background, we hypothesized that the regional balances of gut microbiota might be disturbed by aging. Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare the gut microbiota between terminal ileum and cecum of old rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Animals and sample collection

Specific pathogen-free male Fisher-344 rats at age 74-week-old (n = 7) and 2-year-old (n = 7) (Orient Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) were used in this study.

All of protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (permission number: BA1304-127/033), and the procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of South Korea. Rats were bred in a humidity-controlled room at 23°C under a 12-hour light-dark cycles. They were provided with unrestricted access to food and water. Rats were terminally anesthetized via inhalation of carbon dioxide. Terminal ileum and cecum samples were extracted and stored at −80°C. Luminal contents of terminal ileum and cecum were collected by washing out the luminal part of each tissue sample with phosphate-buffered saline.

2. DNA extraction, PCR amplification, quantification and metagenome sequencing of 16S rRNA gene

Total bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from the luminal contents of terminal ileum and cecum samples using a G-spin™ genomic DNA extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). DNA quality was evaluated by the 260/280-nm and 260/230-nm absorption ratios measured with NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis. For preparation of MiSeq library amplicons, target gene (16S rRNA V3–V4 region) was amplified using 341F and 805R primers, and the V3–V4 PCR amplicons were attached with Illumina indices and adapters from Nextera® XT Index Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The program of first PCR consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles, where 1 cycle consisted of 94°C for 30 seconds (denaturation), 63°C for 45 seconds (annealing) and 72°C for 1 minute (extension), and a final extension of 72°C for 5 minutes. The procedure for the second round of PCR amplification was 72°C for 3 minutes; 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, repeated for 12 cycles; and 72°C for 5 minutes. Short DNA fragments were eliminated using FavorPrep™ DNA purification kit (Favorgen, Taiwan). The PCR amplicons were quantified by Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After pooling of 300 ng per sample, the PCR products were purified with a FavorPrep™ DNA gel extraction kit (Favorgen, Pintung, Taiwan). Sequencing was performed at Chunlab Inc. (Seoul, Korea) with MiSeq system (Illumina).

3. Metagenome sequencing data analysis

Reads with short lengths and low Q-values were removed by the pre-filter. Non-specific, non-target, and chimeric amplicons were eliminated in the quality control process. Taxonomic assignment was conducted based on the EzBioCloud database at the species level with a 97% similarity cutoff. Singletons were excluded.

Alpha diversity and beta diversity were analyzed in CL community™ ver. 3.42 (Chunlab Inc.). The alpha diversity was assessed by diversity indices (ACE, Chao1, Jackknife, Shannon, and Simpson). The beta diversity was evaluated with un-weighted UniFrac-based principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), a non-parametric multivariate statistical test.

4. Statistical analysis

The differences in alpha- and beta-diversities and abundances of taxa of microbial communities were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test in PASW ver. 18 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Results with P-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics

The quality of metagenome sequencing data and diversity indices are described in Table 1. The mean of total valid reads was 101,740. There was no significant difference of valid reads between ileum and cecum samples both in 74-week-old and 2-year-old rats (74-week-old, P = 0.277; 2-year-old, P = 0.180).

Table 1.

Basal characteristics of metagenome sequencing data and alpha diversity of microbial community from ileum and cecum luminal contents

| Characteristic | 74 wk Ile (n = 7) | 74 wk Cec (n = 7) | P-valuea | 2 yr Ile (n = 7) | 2 yr Cec (n = 7) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid read | 113,226 | 94,207 | 0.277 | 96,832 | 78,015 | 0.180 |

| No. of OTU | 494 | 3,830 | 0.002 | 578 | 3,207 | 0.004 |

| Good’s library coverage (%) | 99.94 | 99.87 | 0.004 | 99.93 | 99.83 | 0.002 |

| Alpha diversity | ||||||

| ACE | 530.01 | 3,870.99 | 0.002 | 596.49 | 3,241.47 | 0.004 |

| Chao1 | 506.02 | 3,833.53 | 0.002 | 582.06 | 3,210.47 | 0.004 |

| Jackknife | 561.00 | 3,947.00 | 0.002 | 624.00 | 3,308.00 | 0.003 |

| Shannon | 1.51 | 4.85 | 0.002 | 1.96 | 4.69 | 0.004 |

| Simpson | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.009 |

| Beta diversity (inter-set distances to ileum) | 0.180 | 0.251 | 0.001 | 0.221 | 0.285 | 0.002 |

Values are presented as median only. Ile, ileum; Cec, cecum; OTU, operational taxonomic unit.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

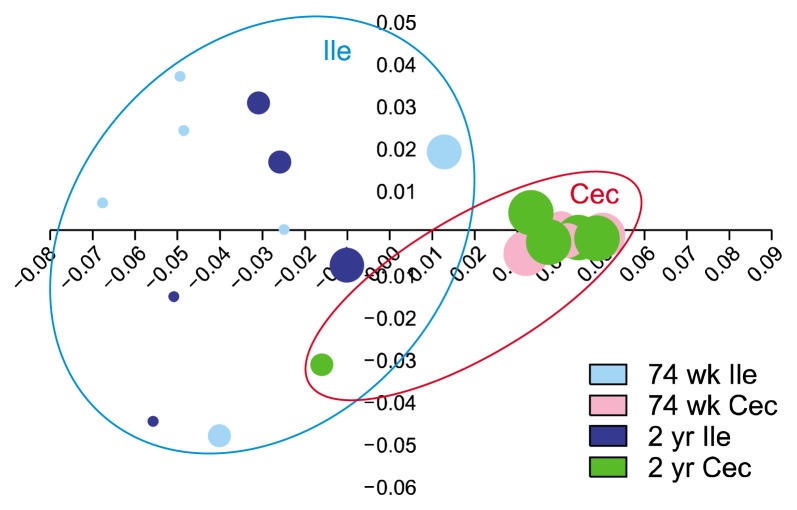

2. Beta diversity of ileal and cecal microbiota

PCoA plot shows the clustering of samples by unweighted UniFrac (Fig. 1). Microbial communities of mostly separated between ileum and cecum. The inter-individual variation was higher among ileum samples than in cecum samples. That is, while microbial communities of ileum samples were scattered, those of cecum samples were closely gathered except one sample (a 2-year-old cecum sample). PERMANOVA results demonstrated the beta set-significance between ileum and cecum both in 74-week-old (P = 0.001) and 2-year-old rats (P = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Unweighted UniFrac-based principal coordinates analysis. Inter-individual variation of microbial communities was higher in ileum than in cecum. Ile, ileum; Cec, cecum. The size of each circle indicate alpha-diversity of microbiota in each individual rat.

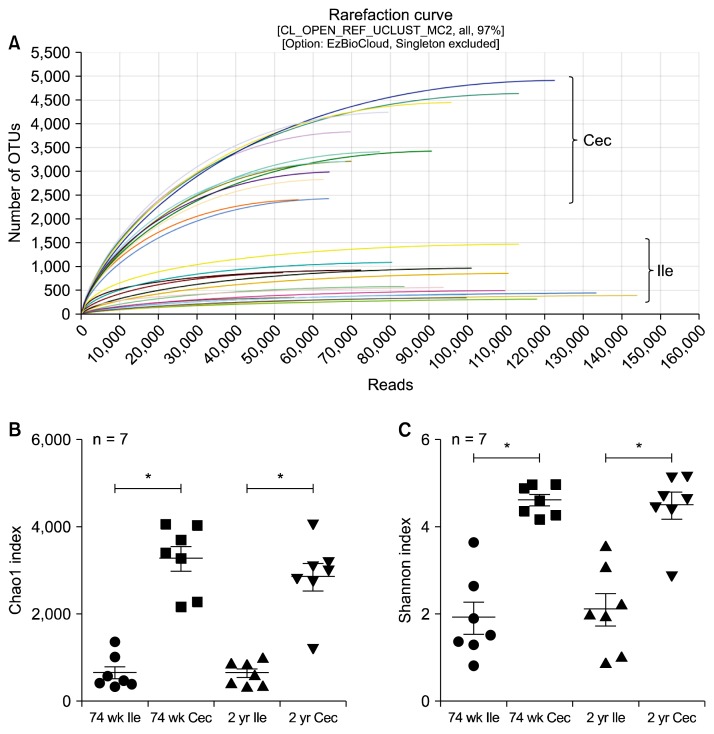

3. Alpha diversity of ileal and cecal microbiota

As indicated with diversity indices (ACE, Chao1, Jackkniffe, Shannon, and Simpson), the diversity of microbial composition was significantly higher in cecum than in ileum, both in 74-week-old and 2-year-old rats (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Alpha-diversity of luminal bacteria in ileum (Ile) and cecum (Cec) of old rats. (A) Rarefraction curves. (B, C) Chao1 and Shannon indices. OTU, operational taxonomic unit. *P < 0.05.

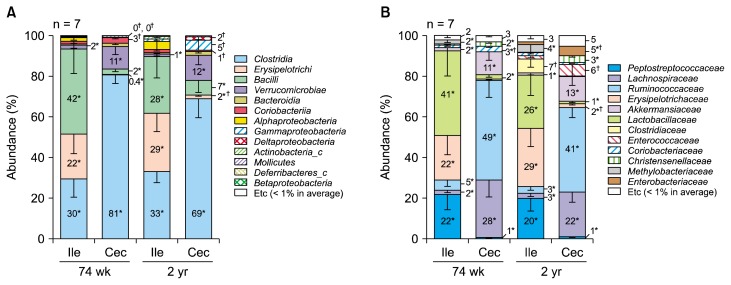

4. Taxonomic composition of ileal and cecal microbiota

In a bacterial class-level, ileal microbiota was enriched with Clostridia, Erysipelotrichi, and Bacilli both in 74-week-old and in 2-year-old rats (Fig. 3A) On the other hand, cecal microbiota of both 74-week-old and 2-year-old was dominated by Clostridia, Bacilli, and Verrucomicrobiae. The relative abundance ratios (%) of Clostridia and Verrucomicrobiae were higher in cecum than in ileum (Clostridia: 74 wk, P = 0.002; 2 yr, P = 0.018; Verrucomicrobiae: 74 wk, P = 0.013; 2 yr, P = 0.018). On the other hand, Erysipelotrichi and Bacilli were decreased in cecum compared to ileum (Erysipelotrichi: 74 wk, P = 0.018; 2 yr, P = 0.003; Bacilli: 74 wk, P = 0.003; 2 yr, P = 0.035). According to age, the percentage of Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria were increased in cecum of 2-year-old rats (Gammaproteobacteria: P = 0.002; Deltaproteobacteria: P = 0.001).

Figure 3.

Abundance ratios of microbiota in the ileum (Ile) and cecum (Cec) luminal samples at (A) class and (B) family level. *P < 0.05, Ile vs. Cec; †P < 0.05, 74-week-old vs. 2-year-old.

In a bacterial family-level, two families in Clostridia class (Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae) were significantly increased in cecum compared to ileum (Lachnospiraceae: 74 wk, P = 0.006; 2 yr, P = 0.004; Ruminococcaceae: 74 wk, P = 0.002; 2 yr, P = 0.002) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, Peptostreptococcus, which is also a class of Clostridia, and Lactobacillaceae were less abundant in cecum than in ileum (Peptostreptococcus: 74 wk, P = 0.009; 2 yr, P = 0.002; Lactobacillaceae: 74 wk, P = 0.003; 2 yr, P = 0.018). According to age, Clostridiaceae increased in ileal microbiota (74 wk, 0.173% ± 0.069%; 2 yr, 7.007% ± 4.066%; P = 0.004). The proportion of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae increased by aging in cecum (Enterococcaceae: 74 wk, 0.002% ± 0.001%; 2 yr, 5.687% ± 5.625%; P = 0.002; Enterobacteriaceae: 74 wk, 0.002% ± 0.002%; 2 yr, 4.567% ± 4.540%; P = 0.002).

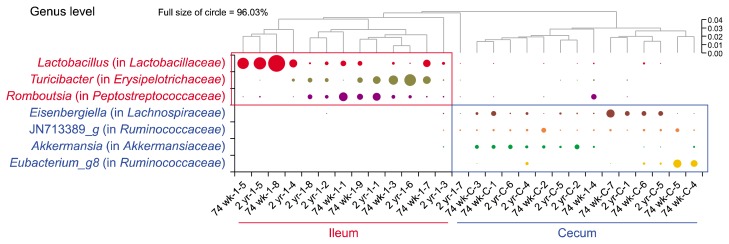

In genus level, the most distinctly abundant genera in ileum were Lactobacillus (belonging to Lactobacillaceae), Turicibacter (a genus of Erysipelotrichaceae), and Romboutsia (belonging to Peptostreptococcaceae). The most distinguishingly dominant genera in cecum were Eisenbergiella (a member of Lachnospiraceae), JN713389_g (a genus of Ruminococcaceae), Akkermansia (belonging to Akkermansiaceae), and Eubacterium_g8 (a genus of Ruminococcaceae) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Heatmap at genus level. Lactobacillus, Turicibacter, and Romboutsia were significantly more enriched in ileum than in cecum while Eisenbergiella, JN713389 (a genus of Ruminococcaceae), Akkermansia, and Eubacterium_g8 were significantly more abundant in cecum than in ileum (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Gut microbiota distributes along the gastrointestinal tract and influences on the host in each gut locations. Some studies have analyzed the bacterial community in different locations along the gastrointestinal tract of mice or rats.9,10 According to the studies, some differences between small intestine and large intestine appear in both young mice and rats. Thus, alpha diversity is higher in cecum than in ileum. In addition, Lactobacillaceae, lactate-producing bacteria, are more abundant in small intestine than in large intestine. On the other hand, Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, some of which ferment carbohydrates and plant aromatic compounds, are more enriched in large intestine. Regional differences in colonic mucosa-associated microbiota result in differential expression of colonic mucosal genes including Toll-like receptors 2 and 4.24 However, most of previous studies have been limited to young animals. In this study, we investigated the regional differences of gut microbiota between ileum and cecum using metagenome sequencing of 16S rRNA gene.

Our study shows lower inter-individual variations in cecal microbiota than in ileal microbiota. The least inter-subject variations in large intestines were demonstrated in mice as well.25 It has been reported that physicochemical properties of small intestine had greater inter-individual variation than in colonic transit.26 We assume that the higher inter-individual variation in ileum may be due to the greater inter-individual variations in the condition of small intestines. There has been a hypothesis that transient microbiota may translocate from the stomach to the duodenum to escape the acidic condition of stomach, so that the large intestines, which are located far from the stomach, may be less affected by the ‘vanishing’ of ‘transient microbiota’.9 Our sequencing results in old rats also revealed that the alpha diversity of microbiota was higher in cecum than in ileum. Regarding this issue, there has been a conflicting report showing the least bacterial diversity in jejunum and ileum, and the greater bacterial diversity in large intestines and feces as well as in duodenum and stomach.9 Nevertheless, this result was consistent with previous results in young rats and pigs, which was in accordance with the traditional concept that the bacterial diversity increases from stomach to feces.10,27

Consistent with previous results in young mice and rats,9,10 the results in old rats showed the higher abundance of Lactobacillaceae (lactate-producing bacteria) in ileum and the enrichment of Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae (butyrate-producing bacteria) in cecum. Some members of Lactobacillaceae, especially Lactobacillus, are presumed to adhere to components of small intestinal mucosa,28 and produce lactate.29 Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae breakdown the complex polysaccharides that are not digested in the upper digestive tract to produce butyrate, the critical energy source for colonocytes.30 The short-chain fatty acids are uptaken by intestinal epithelial cells through both passive and active mechanisms, are utilized as a source of ATP, and they regulate immune cell functions.31 These results indicate that the sources and producers of short chain fatty acids are different between ileum and cecum, and the pattern retains in the old rats as well.

A notable result of this study is that Deltaproteobacteria significantly increased with aging in cecum. Deltaproteobacteria comprises members of sulfate-reducing bacteria that produce H2S, a genotoxic agent,32 which may contribute to inflammatory bowel diseases and colon carcinogenesis.33,34 The sulfate-reducing bacteria are associated to the risk of colorectal cancer in African Americans.35 We presume that this family may contribute to the increase of colon cancer risk in old ages.

Although there was a limitation that young adult rats were not included as an experimental group, we verified the regional differences of gut microbiota in old rats for the first time, to our knowledge. To supplement the limitation, we compared our data with previous reports that demonstrated the profiles of gut microbiota in different locations of gut.

In conclusion, regional distinctions of microbiota between ileum and cecum of old rats appear consistent with young rats. Age-related alterations of gut microbiota in old rats seem to occur in minor compositions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (No. NRF-2016R1A2B4013133).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 2004; 118:229–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stappenbeck TS, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:15451–5. 10.1073/pnas.202604299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:15718–23. 10.1073/pnas.0407076101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowland I, Gibson G, Heinken A, Scott K, Swann J, Thiele I, et al. Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur J Nutr 2018;57:1–24. 10.1007/s00394-017-1445-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2010;90:859–904. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finegold SM, Sutter VL, Mathisen GE. Normal indigenous intestinal flora. In: eds. by Hentges DJ, Human Intestinal Microflora in Health and Disease. New York, Academic Press, pp 3–31, 1983 10.1016/B978-0-12-341280-5.50007-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep 2006;7:688–93. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohland CL, Jobin C. Microbial activities and intestinal homeostasis: a delicate balance between health and disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;1:28–40. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu S, Chen D, Zhang JN, Lv X, Wang K, Duan LP, et al. Bacterial community mapping of the mouse gastrointestinal tract. PLoS One 2013;8:e74957. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D, Chen H, Mao B, Yang Q, Zhao J, Gu Z, et al. Microbial biogeography and core microbiota of the rat digestive tract. Sci Rep 2017;8:45840. 10.1038/srep45840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taschuk R, Griebel PJ. Commensal microbiome effects on mucosal immune system development in the ruminant gastrointestinal tract. Anim Health Res Rev 2012;13:129–41. 10.1017/S1466252312000096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mu C, Yang Y, Su Y, Zoetendal EG, Zhu W. Differences in microbiota membership along the gastrointestinal tract of piglets and their differential alterations following an early-life antibiotic intervention. Front Microbiol 2017;8:797. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, de Weerd H, Flannery E, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108 Suppl 1:4586–91. 10.1073/pnas.1000097107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging. Science 2015; 350:1214–5. 10.1126/science.aac8469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature 2012;488:178–84. 10.1038/nature11319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rampelli S, Candela M, Turroni S, Biagi E, Collino S, Franceschi C, et al. Functional metagenomic profiling of intestinal microbiome in extreme ageing. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5:902–12. 10.18632/aging.100623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;908:244–54. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M, Ostan R, Bucci L, Pini E, et al. Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One 2010;5:e10667. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira RM, Pereira-Marques J, Pinto-Ribeiro I, Costa JL, Carneiro F, Machado JC, et al. Gastric microbial community profiling reveals a dysbiotic cancer-associated microbiota. Gut 2018;67: 226–36. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33:954–64. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong SH, Zhao L, Zhang X, Nakatsu G, Han J, Xu W, et al. Gavage of fecal samples from patients with colorectal cancer promotes intestinal carcinogenesis in germ-free and conventional mice. Gastroenterology 2017;153:1621–33.e6. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SM, Kim N, Jo HJ, Park JH, Nam RH, Lee HS, et al. Comparison of changes in the interstitial cells of Cajal and neuronal nitric oxide synthase-positive neuronal cells with aging between the ascending and descending colon of F344 rats. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;23:592–605. 10.5056/jnm17061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jo HJ, Kim N, Nam RH, Kang JM, Kim JH, Choe G, et al. Fat deposition in the tunica muscularis and decrease of interstitial cells of Cajal and nNOS-positive neuronal cells in the aged rat colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014;306:G659–69. 10.1152/ajpgi.00304.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Devkota S, Musch MW, Jabri B, Nagler C, Antonopoulos DA, et al. Regional mucosa-associated microbiota determine physiological expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in murine colon. PLoS One 2010;5:e13607. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 2005;308:1635–8. 10.1126/science.1110591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deiteren A, Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, Burton D, McKinzie S, Rao AS, et al. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic colon transit measurement in health and irritable bowel syndrome and relationship to bowel functions. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22: 415–23, e495 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quan J, Cai G, Ye J, Yang M, Ding R, Wang X, et al. A global comparison of the microbiome compositions of three gut locations in commercial pigs with extreme feed conversion ratios. Sci Rep 2018;8:4536. 10.1038/s41598-018-22692-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vélez MP, De Keersmaecker SC, Vanderleyden J. Adherence factors of Lactobacillus in the human gastrointestinal tract. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2007;276:140–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter J. Ecological role of lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract: implications for fundamental and biomedical research. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008;74:4985–96. 10.1128/AEM.00753-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2009;294:1–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corrêa-Oliveira R, Fachi JL, Vieira A, Sato FT, Vinolo MA. Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids. Clin Transl Immunology 2016;5:e73. 10.1038/cti.2016.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attene-Ramos MS, Wagner ED, Plewa MJ, Gaskins HR. Evidence that hydrogen sulfide is a genotoxic agent. Mol Cancer Res 2006;4:9–14. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loubinoux J, Bronowicki JP, Pereira IA, Mougenel JL, Faou AE. Sulfate-reducing bacteria in human feces and their association with inflammatory bowel diseases. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2002;40:107–12. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deplancke B, Gaskins HR. Hydrogen sulfide induces serum-independent cell cycle entry in nontransformed rat intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J 2003;17:1310–2. 10.1096/fj.02-0883fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yazici C, Wolf PG, Kim H, Cross TL, Vermillion K, Carroll T, et al. Race-dependent association of sulfidogenic bacteria with colorectal cancer. Gut 2017;66:1983–94. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]