Abstract

Background

Observational studies have linked increased adult height with better cognitive performance and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). It is unclear whether the associations are due to shared biological processes that influence height and AD or due to confounding by early life exposures or environmental factors.

Objective

To use a genetic approach to investigate the association between adult height and AD.

Methods

We selected 682 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with height at genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10−8) in the Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium. Summary statistics for each of these SNPs on AD were obtained from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) of 17,008 individuals with AD and 37,154 controls. The estimate of the association between genetically predicted height and AD was calculated using the inverse-variance weighted method.

Results

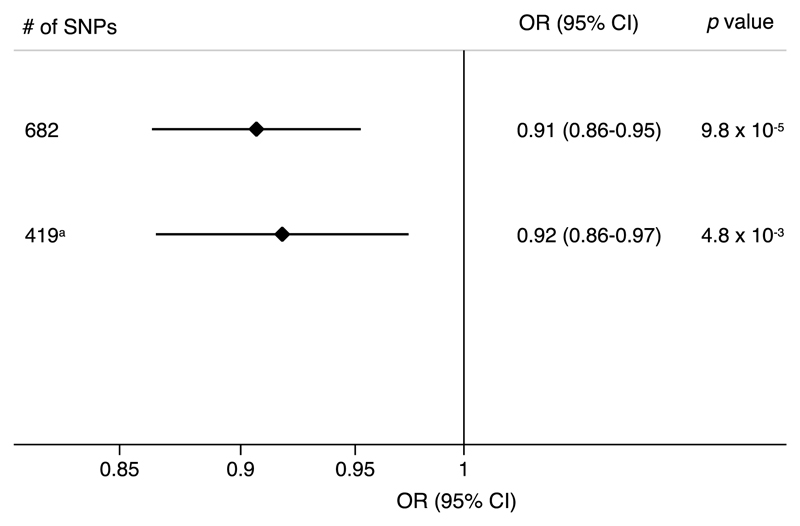

The odds ratio of AD was 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.86–0.95; p = 9.8 × 10−5) per one standard deviation increase (about 6.5 cm) in genetically predicted height based on 682 SNPs, which were clustered in 419 loci. In an analysis restricted to one SNP from each height-associated locus (n = 419 SNPs), the corresponding OR was 0.92 (95% confidence interval, 0.86–0.97; p = 4.8 × 10−3).

Conclusion

This finding suggests that biological processes that influence adult height may have a role in the etiology of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, anthropometry, genetics, polymorphism, single nucleotide

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the major cause of dementia, and a leading cause of disability, morbidity, and mortality [1]. Established non-modifiable risk factors include increasing age and genetic variants in the APOE gene, which encodes apolipoprotein E [1]. Low educational attainment and certain cardiovascular risk factors have been identified as possible modifiable risk factors for AD in observational studies [2, 3], but causal associations of high blood pressure, adiposity, and type 2 diabetes with increased AD risk have not been corroborated by genetic studies [4, 5]. Observational studies have also found that taller stature is associated with better cognitive performance [6–8] and lower risk of dementia and AD [9, 10]. Moreover, a recent study showed a genetic correlation between greater height and cognitive function measured by a verbal-numerical reasoning test [11]. It is unclear whether achieved height may be related to cognitive function and AD via shared underlying genetic and biological factors or whether it only serves as a marker of early life exposures, childhood nutrition, or social and environmental factors that affect the risk of AD. Answers to this question may provide insight into the etiology of AD.

Genetic variants that influence a specific risk factor can be used as instrumental variables to investigate the association between the risk factor and disease risk. This genetic approach has been utilized to explore the association between adult height and risk of cardiovascular disease [12, 13] and cancer [14–16], but has not yet been used to investigate the association between height and AD. The aim of this study was to examine whether genetically predicted height is associated with AD. We used data for nearly 700 genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms; SNPs) that explain one-fifth of the heritability for height, identified in the Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium [17], as well as AD-associated data for the same genetic variants from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP).

Methods

Alzheimer’s disease data

This study was performed using summary statistics for SNP–AD associations obtained from the IGAP consortium [18]. IGAP includes genetic data from 17,008 individuals with AD and 37,154 controls of European ancestry. We used data from the first stage of IGAP, which genotyped and imputed data on 7,055,881 SNPs to meta-analyze genome-wide association studies datasets from four consortia, including the Alzheimer Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC), the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology consortium (CHARGE), the European Alzheimer’s disease Initiative (EADI), and the Genetic and Environmental Risk in AD consortium (GERAD). All AD cases met internationally accepted criteria for possible, probable (National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, DSM-IV), or definite (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease) AD [18]. All studies included in IGAP had been approved by an Institutional Review Board. Informed consent had been obtained from participants or from a caregiver, legal guardian, or other proxy.

Selection of genetic variants

A genome-wide meta-analysis comprising 253, 288 European-descent individuals from 79 studies included in the GIANT consortium identified 697 SNPs associated with adult height at genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10−8) [17]. The SNPs were clustered in 423 loci, with a locus defined as one or multiple jointly associated SNPs located within a 1 Mb window [17]. The 697 height-associated SNPs were considered for inclusion in the present analysis. For 15 SNPs neither the index SNP nor any proxies (defined as SNPs with linkage disequilibrium R2 >0.9) was available in the IGAP dataset, leaving 682 SNPs for inclusion in the analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The majority of SNPs were uncorrelated, but some SNPs in close physical proximity (for example in the same locus) were in partial linkage disequilibrium [17]. We therefore also conducted an analysis that included the lead SNP (i.e., the SNP with the smallest p value) from each locus and which had corresponding data in IGAP; this analysis included 419 SNPs from separate height-associated loci.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed by assessing the height-related SNPs’ associations with AD risk, weighting the effect of each SNP by the magnitude of its association with height. Estimates for individual SNPs were combined using an inverse-variance weighted approach [19]. We estimated the genetic correlation between height and AD using LD score regression [20], based on data available from LD Hub (http://ldsc.broadinstitute.org). The reported odds ratios (OR) represent the association of a one standard deviation (SD) increase (about 6.5 cm) in genetically predicted height with AD. All statistical tests were two-sided. Individual height-associated SNPs were investigated for association with AD using a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (p < 7.3 × 10−5 [0.05/682 SNPs]). Tests were otherwise considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses, we used the weighted median method and Egger regression analysis to explore and adjust for pleiotropy [19]. Pleiotropic associations with birth weight and educational attainment, both of which show a genetic correlation with adult height [11, 21, 22], were investigated by excluding height-associated SNPs that were associated with birth weight [22] or years of education [23] at p < 0.05 (Supplementary Table 1). Pleiotropic SNPs were identified by searching the PhenoScanner database [24]. We also repeated the analysis with the exclusion of SNPs associated with AD at p < 0.05 to assess the influence of SNPs that were more strongly associated with AD.

Results

Of the 682 height-associated SNPs, 56 were associated with AD at nominal statistical significance (p < 0.05) but none of the associations remained at a Bonferroni-corrected significance level (Supplementary Table 1). In an inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis, in which estimates of all 682 SNPs were combined, the OR of AD per 1 SD increase (about 6.5 cm) in genetically predicted height was 0.91 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86–0.95; p = 9.8 × 10−5) (Fig. 1). The association was similar when the analysis was restricted to one SNP from each height-associated locus (n = 419 SNPs) (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86–0.97; p = 4.8 × 10−3) (Fig. 1). A genetic correlation between height and AD was observed in LD score analysis (Rg = −0.162; p = 9.0 × 10−3).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios of Alzheimer’s disease per one standard deviation increase (about 6.5 cm) in genetically predicted adult height based on 682 and 419 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR, odds ratio. aThis analysis is restricted to one SNP from each height-associated locus.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the association between genetically predicted height and AD. Analyses using the weighted median and Egger regression methods yielded similar OR estimates but with lower precision (wider CI), and there was no evidence of pleiotropy (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). The association also remained after exclusion of 97 SNPs associated with birth weight and in a separate analysis excluding 204 SNPs associated with years of education (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, the association was similar when 56 SNPs associated with AD at p < 0.05 were excluded (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that a genetic predisposition to higher adult height is inversely associated with AD. Our finding confirms and extends the results from observational studies that have shown that taller height is associated with improved cognitive performance [6–8], lower rates of death from dementia [9], and reduced risk of AD [10]. The association between genetically predicted height and AD is in the same direction as the genetic association between height and risk of cardiovascular disease [12, 13] but opposed the direction for certain cancers [14–16].

A possible explanation for the observed association between genetically predicted height and AD is that genetic variants that affect height also influence biological pathways that are involved in the development of AD. Biological pathways recently revealed to possibly influence height include signaling pathways for bone morphogenetic protein, transforming growth factor-beta, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, axon-guidance (the process whereby growing nerve fibers find their targets in the developing brain), and STAT3 [13, 17]. Members of the bone morphogenetic protein family of growth factors have been implicated as crucial modulators of neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus [25, 26] and have been demonstrated to affect amyloid-β-induced neurotoxicity [27, 28] and amyloid plaque burden [29]. In addition, available evidence indicates involvement of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 [30] and STAT3 [31] signaling in AD.

A strong genetic correlation between birth weight and adult height (Rg = 0.41; p = 4.8 × 10−52) was recently reported [22]. It was revealed that the association between the birth weight-raising alleles and adult height were concentrated among a subset of loci, including HHIP and GNA12 [22]. Genetic variants in those loci are not associated with AD in the IGAP cohort and the association between genetically predicted height and AD remained after the exclusion of birth weight-associated variants. This suggests that confounding by birth weight does not explain the height-AD relationship.

Strengths of this study include the use of multiple genetic variants that explain a large proportion (about 20%) of the heritability for height as well as large number of AD cases and controls. The use of a large number of genetic variants and the large sample size increased the statistical power and the possibility to detect an association. A limitation is that summary-level data for AD were available for men and women combined only. Hence, we could not examine whether there was a sex-specific association between genetically predicted height and AD. Moreover, because the IGAP cohort only included individuals of European ancestry, our results might not be generalizable to other ethnicities.

Using a genetic approach to investigate the association between height and AD reduces potential confounding by early life experiences, such as childhood nutrition. However, it does not exclude the possibility that the association may be explained by behaviors or lifestyle choices adopted by taller individuals. A recent study showed that genetically predicted height was associated with measures of socioeconomic status, including older age of completing full time education, higher odds of working in a skilled profession, and higher annual household income [21]. Several genetic variants that affect height also influence educational attainment [23], which has been associated with AD in observational studies [2]. In the present study, the association between genetically predicted height and AD remained after exclusion of genetic variants related to educational attainment, and there was no evidence of pleiotropy in the sensitivity analysis using Egger regression. Nevertheless, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that the inverse relationship between genetically predicted height and AD may partially be mediated by higher socioeconomic status or dietary and lifestyle choices (e.g., physical activity and alcohol consumption) adopted by taller people and which may reduce the risk of AD.

In conclusion, this study showed that a genetic predisposition to higher adult height is associated with a lower risk of AD. This suggests that biological processes that influence height may have a role in the etiology of AD.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170528.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Young Scholar Award (to Susanna C. Larsson) from the Karolinska Institutet’s Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology (SFO-EPI). Hugh S. Markus and Matthew Traylor have infrastructural support from the Cambridge University Trusts NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. Hugh S. Markus is supported by a NIHR Senior Investigator award. The authors thank the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) for providing summary-level data for these analyses. The investigators within IGAP contributed to the design and implementation of IGAP and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. IGAP was made possible by the generous participation of the control subjects, the patients, and their families. The i–Select chips was funded by the French National Foundation on Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. EADI was supported by the LABEX (laboratory of excellence program investment for the future) DISTALZ grant, Inserm, Institut Pasteur de Lille, Université de Lille 2 and the Lille University Hospital. GERAD was supported by the Medical Research Council (Grant n° 503480), Alzheimer’s Research UK (Grant n° 503176), the Wellcome Trust (Grant n° 082604/2/07/Z) and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): Competence Network Dementia (CND) grant n° 01GI0102, 01GI0711, 01GI0420. CHARGE was partly supported by the NIH/NIA grant R01 AG033193 and the NIA AG081220 and AGES contract N01–AG–12100, the NHLBI grant R01 HL105756, the Icelandic Heart Association, and the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University. ADGC was supported by the NIH/NIA grants: U01AG032984, U24AG021886, U01AG016976, and the Alzheimer’s Association grant ADGC–10–196728.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/17-0528r1).

References

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meng XF, Yu JT, Wang HF, Tan MS, Wang C, Tan CC, Tan L. Midlife vascular risk factors and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:1295–1310. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Østergaard SD, Mukherjee S, Sharp SJ, Proitsi P, Lotta LA, Day F, Perry JR, Boehme KL, Walter S, Kauwe JS, Gibbons LE, et al. Associations between potentially modifiable risk factors and Alzheimer disease: A mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001841. discussion e1001841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Proitsi P, Lupton MK, Velayudhan L, Newhouse S, Fogh I, Tsolaki M, Daniilidou M, Pritchard M, Kloszewska I, Soininen H, Mecocci P, et al. Genetic predisposition to increased blood cholesterol and triglyceride lipid levels and risk of Alzheimer disease: A Mendelian randomization analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Abbott RD, White LR, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Snowdon DA, Curb JD. Height as a marker of childhood development and late-life cognitive function: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Pediatrics. 1998;102:602–609. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weinstein G, Goldbourt U, Tanne D. Body height and late-life cognition among patients with atherothrombotic disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:145–152. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31825ca9ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].West RK, Ravona-Springer R, Heymann A, Schmeidler J, Leroith D, Koifman K, Guerrero-Berroa E, Preiss R, Hoffman H, Silverman JM, Beeri MS. Shorter adult height is associated with poorer cognitive performance in elderly men with type II diabetes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:927–935. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Russ TC, Kivimaki M, Starr JM, Stamatakis E, Batty GD. Height in relation to dementia death: Individual participant meta-analysis of 18 UK prospective cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:348–354. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.142984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Beeri MS, Davidson M, Silverman JM, Noy S, Schmeidler J, Goldbourt U. Relationship between body height and dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:116–123. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hagenaars SP, Harris SE, Davies G, Hill WD, Liewald DC, Ritchie SJ, Marioni RE, Fawns-Ritchie C, Cullen B, Malik R, Worrall BB, et al. Shared genetic aetiology between cognitive functions and physical and mental health in UK Biobank (N=112 151) and 24 GWAS consortia. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1624–1632. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nuesch E, Dale C, Palmer TM, White J, Keating BJ, van Iperen EP, Goel A, Padmanabhan S, Asselbergs FW, EPIC-Netherland Investigators. Verschuren WM, et al. Adult height, coronary heart disease and stroke: A multi-locus Mendelian randomization meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1927–1937. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nelson CP, Hamby SE, Saleheen D, Hopewell JC, Zeng L, Assimes TL, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Burgess S, Amouyel P, Anand S, et al. Genetically determined height and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1608–1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Thrift AP, Gong J, Peters U, Chang-Claude J, Rudolph A, Slattery ML, Chan AT, Esko T, Wood AR, Yang J, Vedantam S, et al. Mendelian randomization study of height and risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:662–672. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Khankari NK, Shu XO, Wen W, Kraft P, Lindström S, Peters U, Schildkraut J, Schumacher F, Bofetta P, Risch A, Bickeböller H, et al. Association between Adult Height and Risk of Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer: Results from Meta-analyses of Prospective Studies and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang B, Shu XO, Delahanty RJ, Zeng C, Michailidou K, Bolla MK, Wang Q, Dennis J, Wen W, Long J, Li C, et al. Height and breast cancer risk: Evidence from prospective studies and mendelian randomization. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv219. pii: djv219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, Chu AY, Estrada K, Luan J, Kutalik Z, Amin N, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1173–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, DeStafano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier-Boley B, Russo G, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28:30–42. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zheng J, Erzurumluoglu AM, Elsworth BL, Kemp JP, Howe L, Haycock PC, Hemani G, Tansey K, Laurin C, Early Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE) Eczema Consortium. Pourcain BS, et al. LD Hub: A centralized database and web interface to perform LD score regression that maximizes the potential of summary level GWAS data for SNP heritability and genetic correlation analysis. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:272–279. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tyrrell J, Jones SE, Beaumont R, Astley CM, Lovell R, Yaghootkar H, Tuke M, Ruth KS, Freathy RM, Hirschhorn JN, Wood AR, et al. Height, body mass index, and socioeconomic status: Mendelian randomisation study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2016;352:i582. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Horikoshi M, Beaumont RN, Day FR, Warrington NM, Kooijman MN, Fernandez-Tajes J, Feenstra B, van Zuydam NR, Gaulton KJ, Grarup N, Bradfield JP, et al. Genome-wide associations for birth weight and correlations with adult disease. Nature. 2016;538:248–252. doi: 10.1038/nature19806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Okbay A, Beauchamp JP, Fontana MA, Lee JJ, Pers TH, Rietveld CA, Turley P, Chen GB, Emilsson V, Meddens SF, Oskarsson S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature. 2016;533:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature17671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Kamat MA, Ellis S, Surendran P, Sun BB, Paul DS, Freitag D, Burgess S, Danesh J, Young R, et al. PhenoScanner: A database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3207–3209. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Crews L, Adame A, Patrick C, Delaney A, Pham E, Rockenstein E, Hansen L, Masliah E. Increased BMP6 levels in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients and APP transgenic mice are accompanied by impaired neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12252–12262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1305-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xu H, Huang W, Wang Y, Sun W, Tang J, Li D, Xu P, Guo L, Yin ZQ, Fan X. The function of BMP4 during neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sun L, Guo C, Liu D, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Song Z, Han H, Chen D, Zhao Y. Protective effects of bone morphogenetic protein 7 against amyloid-beta induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Neuroscience. 2011;184:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sun L, Guo C, Wang T, Li X, Li G, Luo Y, Xiao S. LIMK1 is involved in the protective effects of bone morphogenetic protein 6 against amyloid-beta-induced neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurons. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:543–554. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Burke RM, Norman TA, Haydar TF, Slack BE, Leeman SE, Blusztajn JK, Mellott TJ. BMP9 ameliorates amyloidosis and the cholinergic defect in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:19567–19572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319297110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ribe EM, Lovestone S. Insulin signalling in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes: From epidemiology to molecular links. J Intern Med. 2016;280:430–442. doi: 10.1111/joim.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wan J, Fu AK, Ip FC, Ng HK, Hugon J, Page G, Wang JH, Lai KO, Wu Z, Ip NY. Tyk2/STAT3 signaling mediates beta-amyloid-induced neuronal cell death: Implications in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6873–6881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0519-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.