ABSTRACT

Background: Since 2007, trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine has been provided free-of-charge to older adults aged ≥60 years in Beijing, China, but the data regarding influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) among these people are very limited so far. We sought to estimate influenza VE against medically-attended laboratory-confirmed influenza illness among older adults during the 2013–2014 season.

Methods: The influenza-like illness (ILI) patients aged 60 years and older who participated in the influenza virological surveillance of Beijing during 2013–2014 influenza season were recruited in this study. A test-negative design was employed to estimate influenza VE among older adults by using logistic regression models. VE was estimated using logistic regression, adjusted for sex, age, interval (days) between illness onset and specimen collection, and week of illness onset.

Results: Between 1 November, 2013 and 30 April, 2014, a total of 487 elderly ILI patients were enrolled in the study, including 133 influenza-positive cases (of whom 6.8% were vaccinated) and 354 influenza-negative controls (of whom 10.2% were vaccinated). Among 133 influenza-positive cases, 51 tested positive for A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, 22 positive for A(H3N2) virus, 52 tested positive for B/Yamagata-lineage virus, 2 positive for B/Victoria-lineage virus, 1 positive for both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses, and 5 tested positive for viruses of unknown subtype or lineage. The adjusted overall VE was estimated as 32% (95% CI:-48-69), with 59% (95% CI: −79–90) against A(H1N1)pdm09, 22% (95% CI: −253-83) against A(H3N2) and −20% (95% CI: −239-58) against B/Yamagata-lineage viruses.

Conclusions: These results suggested a modest protective effect of the 2013–2014 influenza vaccine among older adults in Beijing which was not statistically significant, with higher VE against the A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses compared to A(H3N2) and B viruses.

KEYWORDS: China, effectiveness, elderly, influenza, test-negative design, vaccination

Introduction

Influenza virus infection is an important risk factor of severe morbidity/mortality cases in elderly people.1 Influenza vaccination is recognized worldwide as an effective method for preventing influenza infection and complications, reducing influenza-attributable mortality and hospitalization rates among elderly people.2-4 Although the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends an annual influenza vaccination with the northern hemisphere trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3) for older adults as World Health Organization (WHO) recommended,5 older adults must pay an out-of-pocket fee for their influenza vaccinations in most cities of China. Since 2007, trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3) has been provided free-of-charge for the registered permanent residents among the elderly aged ≥60 years prior to the wintertime influenza seasons in Beijing, China.6

The circulating influenza virus strains varied greatly by country during 2013–2014 influenza season in the Northern Hemisphere. In the U.S. and Canada, influenza A (H1N1) virus predominated in the early and peak season, and there appeared a mild epidemic of influenza B virus in the late season.7,8 In the European countries, influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 and A (H3N2) viruses co-circulated, while the activity of influenza B virus was extremely low.9,10 In China, influenza A (H1N1)pdm09, A (H3N2) and B viruses co-circulated.11 The studies regarding influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) during 2013–2014 influenza season in North America and the European countries demonstrated a sound effectiveness against influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses.7-10 However, the report regarding the influenza VE against A (H3N2) viruses during 2013–2014 influenza season was absent in North America because of extremely low activity of A (H3N2) viruses, and a great variation in VE results against A(H3N2) viruses was observed in the European countries during this season. In addition, the data of influenza VE in 2013–2014 season were very limited in Asian countries including China. Our study in Beijing provided valuable reference to find out the influenza epidemic characteristics and VE in 2013–2014 season in this region.

During the 2013–2014 season, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2), and B viruses co-circulated in Beijing, China. Since 2013–2014 influenza season, influenza vaccination records of the older adults aged ≥60 years who received influenza vaccine were collected by staff administering vaccinations directly and entered into a newly established electronic registry system in Beijing in order to improve the accuracy of immunization information. Therefore, an opportunity was provided to estimate the influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2), and B viruses during 2013–2014 influenza season simultaneously in Beijing.

In this study, we used a test-negative design to estimate the overall or type/subtype-specific VE against medically-attended influenza illness among the older adults aged ≥60 years during the 2013–2014 influenza season in Beijing, and describe the genetic features of representative strains that circulated in Beijing during the season.

Results

Participant characteristics

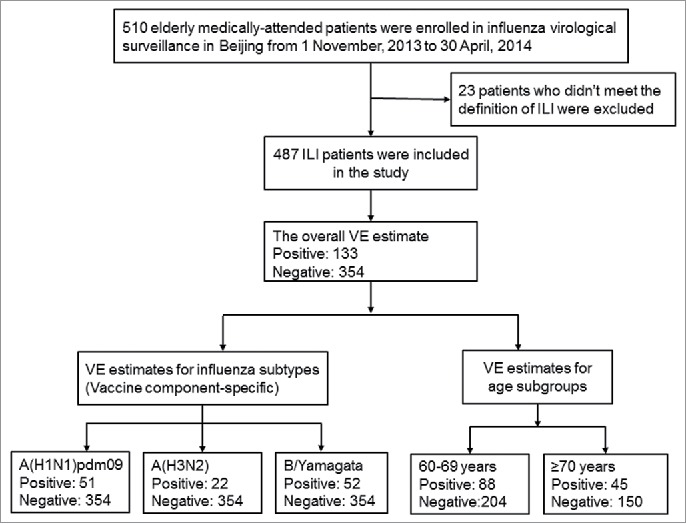

From 1 November 2013 to 30 April 2014, a total of 510 elderly medically-attended ILI patients were enrolled in this study. Among those enrolled, 23 were excluded from the VE analysis for the following reasons: 8 had a fever<38°C;15 had a fever ≥ 38°C with neither cough nor sore throat. Of the remaining 487 patients who were eligible for the analysis in this study (Table 1), 133 (27.3%) were influenza virus positive, including 74 (55.6%) infected with influenza A virus, 54 (40.6%) infected with influenza B virus, and 5 (3.8%) tested positive for viruses of unknown subtype or lineage. Among cases for whom influenza virus subtype/lineage could be determined, 51 were A(H1N1)pdm09, 22 were influenza A(H3N2), 52 were influenza B/Yamagata, 2 were influenza B/Victoria, and one patient was positive for both influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of enrolled elderly patients with medically attended ILI and vaccination status for the 2013–2014 influenza season.

| Characteristic | Influenza positives No. (Col.%) | Influenza negatives No. (Col.%) | P value | Vaccinated No. /total(Row %) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 133 (100) | 354(100) | 45/487(9.2) | ||

| Age | |||||

| 60–69 y | 88 (66.2) | 204 (57.6) | 0.087 | 18/292 (6.2) | 0.004 |

| ≥70 y | 45 (33.8) | 150 (42.4) | 27/195 (13.8) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 70 (52.6) | 187 (52.8) | 0.970 | 32/257 (12.5) | 0.010 |

| Female | 63(47.4) | 167 (47.2) | 13/230 (5.7) | ||

| Interval between illness onset and sample collection | |||||

| ≤ 3 days | 118 (88.7) | 341 (96.3) | 0.001 | 47/480 (9.8) | 0.286 |

| > 3 days | 15 (11.3) | 13 (3.7) | 1/30 (3.3) |

Median age was 65 years (interquartile range [IQR], 62–74 years) for case patients and 67 years (IQR, 62–77 years) for control patients (P<0.001). The median interval between illness onset and sample collection was 1 day for both case and control groups, and the respiratory specimens of 94.3% (459/487) patients were collected within 3 days of illness onset. No patients used antiviral drug before the sample collection. There was a lower proportion of patients enrolled within 3 days of illness onset among case patients (P = 0.001). Case patients and control patients did not differ significantly by age group and sex (Table 1).

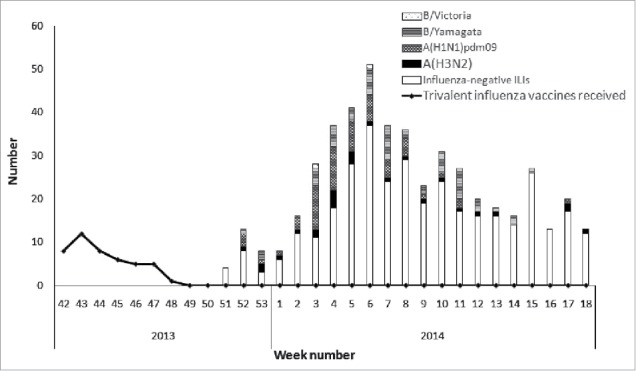

The interval between vaccination and symptom onset was ≥14 days for all elderly patients who received the 2013–2014 season influenza vaccine. The rate of influenza vaccination among all elderly patients aged ≥60 years was 9.2% (45/487). The difference of vaccination coverage between cases (6.8%) and controls (10.2%) was not statistically significant (P = 0.248) (Table 2). Vaccination coverage was higher among the elderly patients aged ≥70 years than those aged 60–69 years old (P = 0.004). Compared with unvaccinated participants, vaccinated individuals were more likely to be male (P = 0.010) (Table 1). Most of the vaccinated study participants received IIV3 between weeks 42 to 47, 2013; laboratory-confirmed influenza cases mainly occurred from week 52, 2013 onwards (Fig. 2). Median time of influenza-positive cases from influenza vaccination to individual illness onset was 145 days (range: 54–156 days).

Table 2.

Number and percentage receiving 2013–2014 seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine among influenza positive and negative elderly patients aged ≥60 years, with estimates of vaccine effectiveness during 2013–2014 season in Beijing, China.

| Influenza positivesa | Influenza negatives | Vaccine effectiveness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Vaccinated no./total (Row %) | Vaccinated no./total (Row%) | Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjustedb(95% CI) |

| Overall | 9/133 (6.8) | 36/354 (10.2) | 36(-37 to 70) | 32 (−48 to 69) |

| Age group | ||||

| 60-69y | 4/88 (4.5) | 14/204 (6.9) | 35(−102 to 79) | 36 (−106 to 80) |

| ≥70y | 5/45 (11.1) | 22/150 (14.7) | 27(−104 to 74) | 20 (−131 to 72) |

| Influenza type | ||||

| Influenza A | 4/74 (5.4) | 36/354 (10.2) | 49(−49 to 82) | 49(−51 to 82) |

| Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 | 2/51 (3.9) | 64 (−55 to 92) | 59 (−79 to 90) | |

| Influenza A(H3N2) | 2/22 (9.1) | 12(−294 to 80) | 22(−253 to 83) | |

| Influenza B | 5/54 (9.3) | 10 (−141to 66) | −8 (−202 to 62) | |

| Influenza B/Yamagata | 5/52 (9.6) | 6(−152 to 65) | −20(−239 to 58) | |

| Influenza B/Victoria | 0/2 | − | − | |

| Sensitivity analysesc | ||||

| Excluding subjects with interval >3 days | 8/118 (6.8) | 36/341 (10.6) | 38 (−37 to 72) | 37 (−42 to 72) |

Note: Vaccine effectiveness was calculated as 100% × (1 − odds ratio [the odds of vaccination among cases divided by the odds of vaccination among controls]) using unconditional logistic regression models, including 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Influenza positive patients included 22 elderly patients infected with influenza A(H3N2), 51 with A(H1N1)pdm09, 52 with influenza B/Yamagata, 2 with influenza B/Victoria, one with both influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09, and 5 with not (sub)typed influenza viruses.

Adjusted for sex, age, interval (days) between illness onset and specimen collection, and week of illness onset.

Subjects with interval (days) between illness onset and specimen collection >3 days were excluded for sensitivity analyses.

Figure 2.

Timeline of number of subjects receiving influenza vaccine and recruitment of subjects testing negative or positive for influenza by type/subtype during 2013–2014 influenza season in Beijing, China.

Estimation of influenza vaccine effectiveness

The overall unadjusted VE of 2013–2014 IIV3 was 36% (95% CI: −37 to 70) against all medically-attended elderly influenza illness, and the overall adjusted VE was 32% (95% CI: −48 to 69) (Table 2). Adjusted VE against influenza A was 49% (95% CI: −51 to 82). 59% (95% CI: −79 to 90) against the dominant circulating A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, and 22% (95% CI:-253 to 83) against A(H3N2) viruses. Adjusted VE was −8% (95% CI: −202 to 62) against influenza B and −20% (95% CI: −239 to 58) against B/Yamagata-lineage viruses (Table 2) The vaccine effectiveness pointestimates were higher against influenza illness among the older adults aged 60–69years with an adjusted VE of 36% (95% CI:−106 to 80) than aged ≥70years with an adjusted VE of 20% (95% CI: −131 to 72) (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses, the overall VE estimates were higher (37%, 95% CI: −42 to 72) when patients enrolled >3 days since illness onset were excluded (Table 2).

Antigenic and genetic characteristics of vaccine

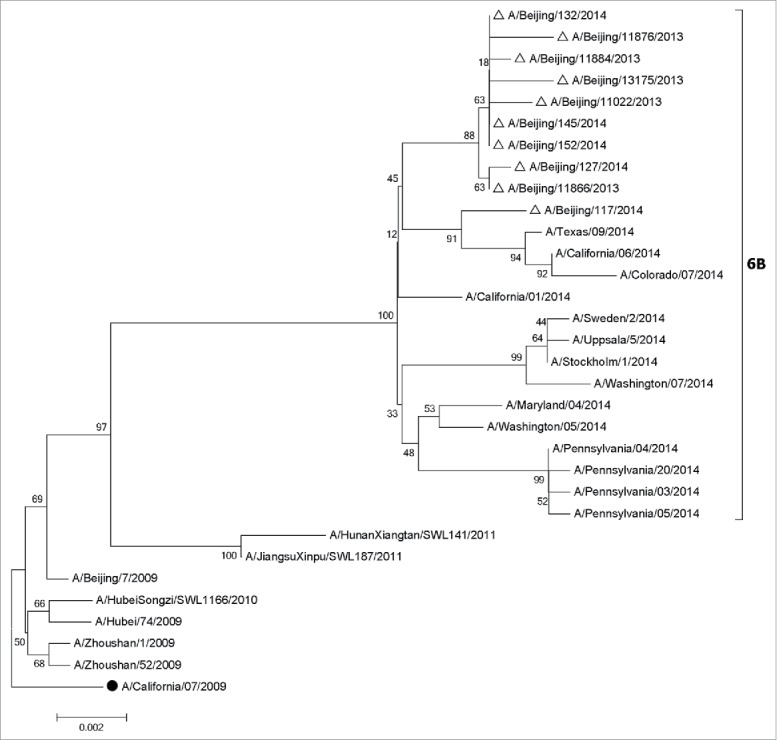

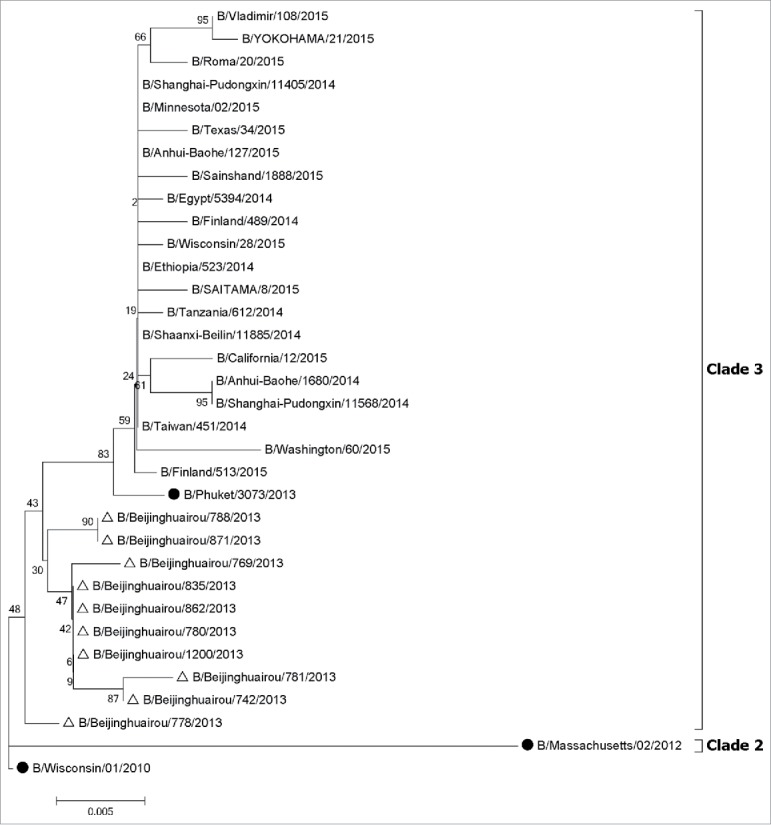

All A (H1N1)pdm09 strains isolated in 2013–2014 influenza season belonged to clade 6B, which did not cluster with the 2013–2014 vaccine strain (A/California/07/2009) (Fig. 3). Most analyzed A(H3N2) strains isolated (88.46%) belonged to clade 3C.3 and few 3C.2 viruses were also observed in 2013–2014 influenza season (Fig. 4). None belonged to the H3N2 vaccine clade (A/Texas/50/2012, clade 3C.1) recommended for the 2013–2014 season. All B/Yamagata strains isolated in 2013–2014 influenza season belonged to clade 3, which was different with vaccine strain B/Massachusetts/2/2012 (Clade 2) (Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Phylogentic analysis of HA genes of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses from influenza virological surveillance during the 2013–2014 season in Beijing, China. The influenza viruses analyzed in this study were indicated with hollow triangles, and the vaccine strains were shown with solid dots. •, vaccine strains. △, the strains isolated in 2013–2014. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replications.

Figure 4.

Phylogentic analysis of HA genes of influenza H3N2 viruses from influenza virological surveillance during the 2013–2014 season in Beijing, China. The influenza viruses analyzed in this study were indicated with hollow triangles, and the vaccine strains were shown with solid dots. •, vaccine strains. △, the strains isolated in 2013–2014. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replications.

Figure 5.

Phylogentic analysis of HA genes of influenza B-Yamagata lineage viruses from influenza virological surveillance during the 2013–2014 season in Beijing, China. The influenza viruses analyzed in this study were indicated with hollow triangles, and the vaccine strains were shown with solid dots. •, vaccine strains. △, the strains isolated in 2013–2014. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replications.

Discussion

In this study, we used a test-negative design to estimate the influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2) and B viruses simultaneously among the older adults aged ≥60 years in Beijing, China during the 2013–2014 season by taking advantage of a newly established electronic registry system to obtain influenza vaccination records of the older adults to reduce recall bias. Our results suggest that the effect of influenza vaccination against medically attended influenza illness among the older adults aged ≥60 years in the 2013–2014 influenza season in Beijing was modest, with moderate VE against A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, suboptimal VE against A(H3N2) virus and poor VE against B virus.

In this study, our adjusted VE estimate against A(H1N1)pdm09 virus (59%) during 2013–2014 season was very close to those of the same season in the USA (≥65 years: 59%) and Canada (≥65 years: 60%), and similar to that in a multicentre case-control study in six European Union (EU) countries (≥60 years: 51.8%). Although the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus strains circulating in Beijing during 2013–2014 season fell into clade 6B and did not cluster with the 2013–2014 vaccine strain (A/California/07/2009), the WHO reported that the majority of A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses circulating during 2013–2014 season remained antigenically homogeneous and closely related to the vaccine virus A/California/7/2009.12 Therefore, the 2013–2014 vaccine conferred a favorable VE against A(H1N1)pdm09 virus during this season.

In this study, our adjusted VE estimate against H3N2 virus was modest (22%), similar to those for all ages in the multicentre case-control study in six European Union (EU) countries (30.2%) and in a study in the Greece (28.3%), but lower than that in the Netherlands (46%).9,10,13 The VE estimates against A(H3N2) virus are very heterogenous by country in European Union (EU) countries during 2013–2014 season ranging from −46.4% in Germany to 80.1% in Hungary.9 The suboptimal VE in this study may result from the genetic mismatch between the circulating virus strains in Beijing and the vaccine strain as well as the egg-adapted changes of the vaccine strain. Our phylogenetic analysis showed that the A(H3N2) virus strains in Beijing belonged to clades 3C.3 and 3C.2, while the 2013–2014 H3N2 vaccine strain (includes A/Texas/50/2012) fell into clade 3C.1. In addition, the WHO reported that the majority of cell-propagated A(H3N2) viruses circulating during 2013–2014 season had 8-fold or greater HI titre reductions compared to the homologous titre for the egg-propagated A/Texas/50/2012 virus although it was recommended that A/Texas/50/2012 was used to replace earlier A/Victoria/361/2011-like vaccine viruses as the 2013–2014 H3N2 vaccine component due to adaptation to propagation in eggs.12

Influenza B viruses gradually replaced influenza A viruses and became the dominant strains in the later stage of 2013–2014 influenza season in Beijing. 96% of Influenza B viruses belonged to B/Yamagata lineage, and little or no effect of 2013–2014 IIV3 was found to against B/Yamagata strains (−20%) in the present study. Our phylogenetic analysis showed that the B/Yamagata viruses collected during the 2013–2014 season (clade 3) were clade-level mismatched to vaccine reference component (B/Massachusetts/2/2012; clade 2). As reported by the WHO, geometric mean HI titres of antibodies against B/Yamagata lineage clade 3 viruses induced by vaccines containing B/Massachusetts/2/2012 antigens were reduced significantly compared to HI titre to the clade 2 vaccine virus.14,15 Besides the clade-level variation, the low VE was also probably attributable to the waning immunity in response to the vaccine, since the older adults in Beijing received influenza vaccine in October and November and the level of antibody titer generated in response to the vaccine may have declined in March of the following year when influenza B epidemics peak during 2013–2014 season.

The vaccination coverage was higher in the elderly patients aged ≥70 years than patients aged 60–69 years, while the latter group has a higher VE. This finding showed that the much older adults would be expected to have more frequent healthcare seeking behaviors and be more likely to receive annual influenza vaccination. However, the reduction in vaccine effectivenss with age was significant. This result could be explained by a progressive decline in immune function with aging.16 Influenza vaccine response could be affected by a certain of age-associated factors, such as multi-morbidity, frailty, and functional dependence accelerate changes in a number of body systems.17 The antibody response of the elderly people is less robust, with lower titers, and exhibits reduced affinity maturation.18 In this study, the elderly patients aged ≥70 years may represent a more vulnerable group, and thus have a weaker response to vaccination compared with the relatively younger patients.

The limitations of this study need to be considered. First, influenza virus was detected using virus isolation in this study rather than real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay, which may decrease the positive rate of influenza due to the relatively lower sensitivity of virus isolation,19 and thus may have underestimated VE compared with studies using RT-PCR. Second, we were unable to adjust for comorbidity due to the absence of this information, but we adjusted VE for age group, which is likely to be correlated with comorbidity. Other test-negative VE studies have shown that adjustment for comorbidity only resulted in minor changes in the VE estimates.8 It is unlikely that the effect of confounding is tremendous that would dramatically change the estimates, but we cannot exclude the possibility that some residual confounding with comorbidity does exist. Third, we lacked information on past infections and immune profiles, and thus the possible effect of prior year vaccination on current year vaccination effectiveness cannot be evaluated. Finally, the small number of specimens may be insufficient to represent genetic characteristics of 2013–2014 epidemic strain in Beijing, though we selected influenza-positive specimens randomly from sentinel surveillance systems for phylogenetic analysis. However, other studies also showed the similar phylogenetic characteristics of influenza viruses during 2013–2014 in Beijing,20 which may support the result of phylogenetic analysis in this study.

In conclusion, our epidemiological data suggest a modest protective effect of the 2013–2014 influenza vaccine against medically attended influenza illness among the older adults in Beijing during 2013–2014 season, mainly against the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. Such results suggested that influenza vaccination is still considered useful among older adults during 2013–2014 season. Consistent long-term studies are required in the future to evaluate the protect effect of influenza vaccine among older adults.

Methods

Subjects enrollment and laboratory diagnosis

The older adults aged 60 years and older with ILI (i.e., temperature ≥ 38°C and either cough or sore throat) who were enrolled in the influenza virological surveillance system of Beijing between 1 November, 2013 and 30 April, 2014 were recruited in this study.

Twenty three hospitals from 16 districts in Beijing were selected as sites for collecting specimens. Pharyngeal swabs of 20 or more patients with ILI who visited the outpatient clinic within 3 days of illness onset were prior collected from the hospitals by trained nurses per week. Pharyngeal specimens collected were stored in the refrigerator at 4°C, and transported in a cool box with ice packs to 1of 18 collaborating laboratories managed by Beijing CDC within 24h after collection. Upon received by the collaborating laboratory, the respiratory specimens were immediately inoculated into Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, and subsequently cultured in an incubator at 33–35°C. After incubation within a period of ≤7 days, influenza viruses in cell cultures were identified using hemagglutination assay (HA) and hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays. All the assays were conducted in Biosafety Level 2 (BSL2) laboratories by well-trained staffs according to standard operating procedures of influenza issued by WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza in China. Details of the formulation, sites and enrollment procedures of influenza virological surveillance system in Beijing were similar with those in the previous reports.21,22

Study design and data collection

A test-negative design was used to estimate influenza VE.21,23,24 Cases were elderly medically-attended ILIs aged ≥60years who tested positive for influenza by virus isolation. Controls were elderly medically-attended ILIs aged ≥60years who tested negative for influenza. As annual influenza immunization campaigns typically commence in the middle of October across Beijing, and increased influenza virus circulation typically begins in early November, pharyngeal specimens collected from 1 November 2014(week 44) were eligible for inclusion in the primary VE analysis (Fig. 1). Patients were excluded if they had been vaccinated within 14 days before symptom onset. Information of enrolled patients was recorded by nurses using a standard questionnaire at specimen collection, including demographic characteristics, onset date, specimen collection date. The questionnaire was sent along with respiratory specimens to the collaborating laboratory. Vaccination status was checked with the vaccination electronic registry system by us.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subject enrollment in the test-negative design study for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness among the older adults during the 2013–2014 influenza season in Beijing, China.

Virus characterization

In order to assess vaccine-virus match at the genetic level, a subset of influenza-positive specimens from sentinel surveillance systems was chosen and characterized by sequencing of the haemagglutinin gene. 13 A(H3N2) strains and 10 B(Yamagata) strains isolated in 2013–2014 were randomly selected and sequenced (2 in Oct 2013, 6 in Nov 2013, 13 in Dec 2013, and 2 in Jan 2014). Viral RNA was extracted using QIAmp Viral Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instruction. For strains, reverse transcription and amplification of HA gene were carried out as described previously.25,26 Then PCR products were sequenced by ABI Prism 3130xl automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) (accession numbers: MG196320-MG196342). Other 23 HA genes of A(H1N1 09pdm) and A(H3N2) strains isolated in 2013–2014, which were sequenced previously, were also enrolled in this study (accession numbers: KM006346-KM006348, KM006350, KM006355-KM006361, KM006371, KM006374, KM006378, KM006381-KM006384, KM006395, KM006397, KM006399, KM006405, KM006406). Nucleotide sequences were assembled and then aligned by MEGA software (ver. 6.0.4).27 Neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogeny trees were inferred with 1000 bootstrap replications.

Data analysis

Questionnaire data were entered using EpiData software. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Median age of cases and controls were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Participant characteristics and vaccination status of cases and controls were compared using χ2 tests. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) comparing cases and controls; VE was calculated as 100% × [1−OR]. We generated separate VE estimates against overall and various types of influenza viruses. Potential confounders (sex, age, interval (days) between illness onset and specimen collection, and week of illness onset) were included in all adjusted VE models. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Ethics

This study was approved by the institutional review board and human research ethics committee of Beijing CDC.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Beijing Science and Technology Planning Project of Beijing Science and Technology Commission (D141100003114001), the Capital Health Research and Development of Special (2014–1–1011), Beijing Health System High Level Health Technology Talent Cultivation Plan (2013–3–098), and Beijing Talents Fund (2014000021223ZK36).

References

- 1.Matias G, Taylor R, Haguinet F, et al.. Estimates of mortality attributable to influenza and RSV in the United States during 1997–2009 by influenza type or subtype, age, cause of death, and risk status. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014;8(5):507–15. doi: 10.1111/irv.12258. PMID:24975705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer WEP, McElhaney J, Smith DJ, et al.. Cochrane re-arranged: support for policies to vaccinate elderly people against influenza. Vaccine. 2013;31(50):6030–3. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.063. PMID:24095882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribeiro A, Cheng PY, Mirza S, et al.. The Impact of seasonal influenza vaccination among persons 60 years and older, on rates of influenza-associated mortality and hospitalization from 1994 to 2009 in Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21:104–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin J, Ridenhour MAC, Kwong JC, Rosella LC, et al.. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccines in preventing influenza-associated deaths and hospitalizations among Ontario residents aged ≥65 years: estimates with generalized linear models accounting for healthy vaccinee effects. PloS One. 2013;8(10):e76318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076318. PMID:24146855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline on seasonal influenza vaccination during the 2007–2008 season in China. Available from: http://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/lxxgm/tbtj/200709/W020130109436359171422.pdf Accessed 5 March 2016.

- 6.Feng L, Mounts AW, Feng Y, et al.. Seasonal influenza vaccine supply and target vaccinated population in China, 2004–2009. Vaccine. 2010;28(41):6778–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.064. PMID:20688038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flannery B, Thaker SN, Clippard J, et al.. Interim estimates of 2013–14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness – United States, February 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(7):137–42. PMID:24553196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Sabaiduc S, et al.. Integrated sentinel surveillance linking genetic, antigenic, and epidemiologic monitoring of influenza vaccine-virus relatedness and effectiveness during the 2013–2014 influenza season. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(5):726–39. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv177. PMID:25784728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valenciano M, Kissling E, Reuss A, et al.. The European I-MOVE Multicentre 2013–2014 Case-Control Study. Homogeneous moderate influenza vaccine effectiveness against A(H1N1)pdm09 and heterogenous results by country against A(H3N2). Vaccine. 2015;33(24):2813–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.012. PMID:25936723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lytras T, Kossyvakis A, Melidou A, et al.. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory confirmed influenza in Greece during the 2013–2014 season: a test-negative study. Vaccine. 2015;33(2):367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.005. PMID:25448097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.China National Influenza Center Influenza report on week 16, 2014;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2014–2015 northern hemisphere influenza season, 20 February 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/2014_15_north/en/. Accessed 18 February 2016.

- 13.Darvishian M, Dijkstra F, van Doorn E, et al.. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the Netherlands from 2003/2004 through 2013/2014: the importance of circulating influenza virus types and subtypes. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0169528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169528. PMID:28068386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO) Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2015–2016 northern hemisphere influenza season, February 2015. Available at: http://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/201502_recommendation.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 18 February 2016.

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO) Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2015 southern hemisphere influenza season, September 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/201409_recommendation.pdf?ua = 1. Accessed 18 February 2016. [PubMed]

- 16.McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(3):379–88. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.008. PMID:21055484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McElhaney JE, Kuchel GA, Zhou X, et al.. T-cell immunity to influenza in older adults: a pathophysiological framework for development of more effective vaccines. Front Immuno. 2016;7:41. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maue AC, Eaton SM, Lanthier PA, et al.. Proinflammatory adjuvants enhance the cognate helper activity of aged CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6129–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804226. PMID:19414765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao RS, Tomalty LL, Majury A, et al.. Comparison of viral isolation and multiplex real-time reverse transcription-PCR for confirmation of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus detection by antigen immunoassays. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(3):527–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01213-08. PMID:19129410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang Q, Gao Y, Chen M, et al.. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of influenza A and B viruses during winter 2013–2014 in Beijing, China. Arch Virol. 2015;160(4):1083–95. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2362-x. PMID:25676826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang P, Thompson MG, Ma C, et al.. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically-attended influenza illness during the 2012–2013 season in Beijing, China. Vaccine. 2014;32(41):5285–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.083. PMID:25092635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang P, Duan W, Lv M, et al.. Review of an influenza surveillance system, Beijing, People's Republic of China. E Infect Dis. 2009;15(10):1603–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1510.081040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine. 2013;31(17):2165–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.053. PMID:23499601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Wu XW, et al.. The test-negative design: validity, accuracy and precision of vaccine efficacy estimates compared to the gold standard of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(37). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, et al.. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch Virol. 2001;146(12):2275–89. doi: 10.1007/s007050170002. PMID:11811679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou B, Lin X, Wang W, et al.. Universal influenza B virus genomic amplification facilitates sequencing, diagnostics, and reverse genetics. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(5):1330–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03265-13. PMID:24501036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, et al.. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. PMID:24132122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]