ABSTRACT

We hypothesize that a pivotal condition determining the efficacy of dog allergen immunotherapy (DAI) might be the mono-sensitization to dog lipocalins (Can f 1-2) in individuals not directly or indirectly exposed to other furry animals. In fact, the concomitant sensitization to lipocalins and/or albumins, especially in those patients directly exposed to furry animals, may potentially stimulate patient's airways by inducing persistent inflammation and, thus, clinical symptoms. In these conditions, it is likely that DAI alone could be inadequate to reduce airway inflammation mediated by inhalation of dog allergens in patients with simultaneous exposure to other furry animals. Can f 5 has been found as exclusive allergen in about one third of dog-sensitized individuals. Considering the presence of different allergenic materials in extract of mammalian origin, it is evident that a standard DAI is not likely to be effective in Can f 5 prevalent or mono-sensitized individuals. Moreover, we would underline the need of collecting detailed information on the possible exposures to furry animals (other than the common pets), an information that usually is neglected in clinical practice. Furthermore, a detailed clinical history exploring the real significance of dog sensitization (mono or poly-sensitization, induction of clinical symptoms after exposure etc.) should be performed before prescribing DAI. In some patients, with potential high susceptibility to animal allergens, the use of CRD is essential to verify the presence of concomitant allergic sensitization to lipocalins and/or albumins belonging to other furry animals. The availability of CRD introduced the possibility of a better targeted prescription of DAI because it might be useful for point out the primary allergens and for the exclusion of cross-reactive ones.

KEYWORDS: Allergic rhinitis, allergic sensitization, bronchial asthma, Can f 5, Component Resolved Diagnosis, dog, dog allergy, hypersensitivity, immunotherapy

To the editor

We read with interest the excellent article of Virtanen T.1 showing the results of a thorough review of publications on allergic sensitization to pet allergens and pet allergen immunotherapy (PAI). We agree with authors’ conclusions that “additional studies of allergen immunotherapy (AIT) for pet associated respiratory allergies are needed, because, as reported in this article, the number of patients is small” and there is the necessity of “ possibly taking advantage of characterized recombinant allergens, novel adjuvants or alternative routes of delivery, ….. “.

It is generally assumed that allergic sensitization to dog is characterized by the main allergens (Can f 1 and Can f 2), which can cross-react with those of other furry animals, whereas sensitization to cat is mainly due to Fel d 1, which recognized by most of cat-allergic individuals and characterized by a lesser degree of cross-reactivity with other animal allergens.2,3 Based on these premises, we would suggest some particular but underestimated clinical conditions (based on our clinical and scientific experience) that might explain the poor clinical efficacy of dog allergen immunotherapy (DAI) in “real life”.

Prevalent sensitization to major dog allergens (Can f 2 and Can f 2) or multiple sensitization to other allergens of furry animals

We previously reported that pet (cat or dog) ownership, or their presence in indoor environments, cannot be considered the main criterion to assess the exposure to furry animals. The use of this criterion represents a potential bias of underestimation in clinical practice and in large epidemiological studies.4-8 In fact, exposure to dogs and cats can occur also by indirect modalities, such as pet allergen-contaminated items.9,10 The indirect modality of exposure may explain the common findings that dog allergens (Can f 1 and Can f 2) can be detected in indoor environments where dogs are not present.11 In developed countries, the consequence of pet allergen ubiquity may induce a persistent stimulation of airways similar, for instance, to that of dust mite, and consequently increase the risk of allergic sensitization.12

For example, in Naples area, less than fifty percent of patients sensitized to cats/dogs or other animals such as horses, rats, mouse, rabbits, hamsters and cows are directly exposed, whereas a significant percentage of subjects are indirectly exposed or not exposed to these allergens.13 A plausible explanation for allergic sensitization in these latter case is a cross-reaction mechanism involving some families of allergenic proteins such as lipocalins [the major allergenic materials derived from dog (Can f 1–2), cattle (Bos d 2), horse (Equ c 1), rat (Rat n 1), mouse (Mus m 1), guinea pig (Cav p 1), rabbit (Ory c 1), hamster (Pho s 21)] and albumins (SA).14,15 Moreover, we have shown, by using an in vivo (skin prick test – SPTs) and in vitro model (the micro-array technique ImmunoCAP ISAC), that exposure and allergic sensitization to common pets may increase the risk of developing sensitization to other furry animals.16,17

Considering this background, we hypothesize that a crucial condition determining the efficacy of DAI may be the mono-sensitization to dog lipocalins (Can f 1–2) in individuals not directly or indirectly exposed to other furry animals. The concomitant sensitization to lipocalins and/or albumins, especially in those patients directly exposed to furry animals, may potentially stimulate patient's airways by inducing persistent inflammation and, thus, clinical symptoms. In other word, DAI alone could be inadequate to reduce airway inflammation mediated by inhalation of dog allergens in patients with simultaneous exposure to other furry animals although the sensitization to ≥2 molecules or to pet albumins was associated with more severe respiratory symptoms".18

Exclusive or prevalent sensitization to dog prostatic kallicrein allergen Can f 5

Dog allergens are a common cause of allergic sensitization and triggering respiratory symptoms worldwide. The impact of dog allergens is particularly relevant in geographical areas characterized by an high level of pet ownership such as US and Northern Europe.19,20

Common described dog allergens belong to lipocalins (Can f 1, Can f 2, Can f 4 and Can f 6) or albumins (Can f 3) families of proteins.14 In 2009 Mattson et al.21 identified a new dog allergen named Can f 5, a prostatic kallicrein which is an androgen-regulated protein expressed in the prostate and detectable only in male dogs (small amounts might also be present in dog epithelia).Recent studies have highlighted the increasing importance of allergic sensitization to Can f 5 which has been found as exclusive allergen in about a third21 until 37% of dog-sensitized individuals.22 However, further studies should confirm the real value of Can f 5 sensitization in “real life”.23

It is well known that literature data on dog allergen immunotherapy (DAI) demonstrated poor and conflicting results on clinical efficacy, probably correlated with the poor-quality extracts and the inherent complex allergenic profile of dog materials.24,25 As a consequence of this and considering the presence of different allergenic materials in extract of mammalian origin, it is evident that a standard DAI is not likely to be effective in Can f 5 prevalent or mono-sensitized individuals. In addition to this probable effect on the efficacy of DAI, patients suffering from this specific sensitization might experience either favourable or unfavourable clinical conditions in “real life”.26 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Possible favourable or unfavourable conditions of being exclusively or prevalently sensitized to dog allergen Can f 5 in “real life”. (Adapted from Liccardi G. et al. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol – 2017).26

| Possible favourable conditions: |

|---|

| Reduction of the risk of cross-reactivity with other common animal allergens. |

| –Can f 5 should not cross-react to other mammalian “pan-allergens” belonging to albumins or lipocalins family.26 |

| Possible reduction of the occurrence of dog allergen «ubiquity» and consequent effects. |

| - To the best of our knowledge, no studies have previously demonstrated a passive transport of Can f 5 in dog-free indoor environments.26 |

| Possibility to own a female dog. |

| – Dog-allergic patients mono-sensitized to Can f 5 seem to tolerate female dogs.31It could to fulfill the wish to get a dog in the house especially in children. |

| Possible utility of castration of male dog ? |

| – Studies are needed. |

| Possible Unfavourable Conditions: |

| Increased risk for allergic sensitization to human seminal fluid. |

| – This condition has been well documented32–34 |

| Possible necessity of re-location of the male dog |

| – In the case of documented occurrence of respiratory symptoms only after exposure to male dogs and not after contact with female dogs.26,31 |

| Possible reduced efficacy of dog AIT ? |

| – Further studies are needed26,30 |

AIT = Allergen Immunotherapy.

The role of CRD as preparatory procedure before prescribing DAI

The component resolved diagnosis (CRD) can be considered a prototype of “Precision Medicine”, since it would allow a better targeted prescription of AIT, by discriminating against primary and cross-sensitization allergens.27 In patients, with potential high susceptibility to animal allergens, the use of ImmunoCAP ISAC is essential to verify the presence of concomitant allergic sensitization to lipocalins and/or albumins belonging to other furry animals.28,29

It is reasonable to assume that individuals with a prevalent or exclusive sensitization to primary dog allergens (Can f 1, Can f 2) have more chances for effective clinical effects following DAI.

Possible future perspectives

Our group previously described a case of dog allergy in which we explored if DAI could interfere with a concomitant allergic sensitization to other allergens of furry animals.30 This demonstrated the efficacy of sublingual DAI on SPTs, symptom score, and pulmonary function, despite the persistent exposure to dog allergens at home in a patient sensitized, but not exposed, to other furry animals. At the best of our knowledge this is the first report suggesting that DAI is able to reduce SPTs responses not only to dog, but also to other furry animals such as rabbit, horse, mouse, rat, hamster, cow. No significant change of wheal diameters induced by cat allergenic extract was acknowledged. This last finding can be easily explained because the primary cat allergen Fel d 1 does not belong to lipocalins’ family and, in the case of our patient, for the high presence of IgE against nFel d 2 (cat SA). Obviously further studies carried out by using different DAI schedules, allergen amount and time of re-evaluation, an adequate number of patients and laboratory evaluation should be performed to confirm our findings.

Concluding remarks

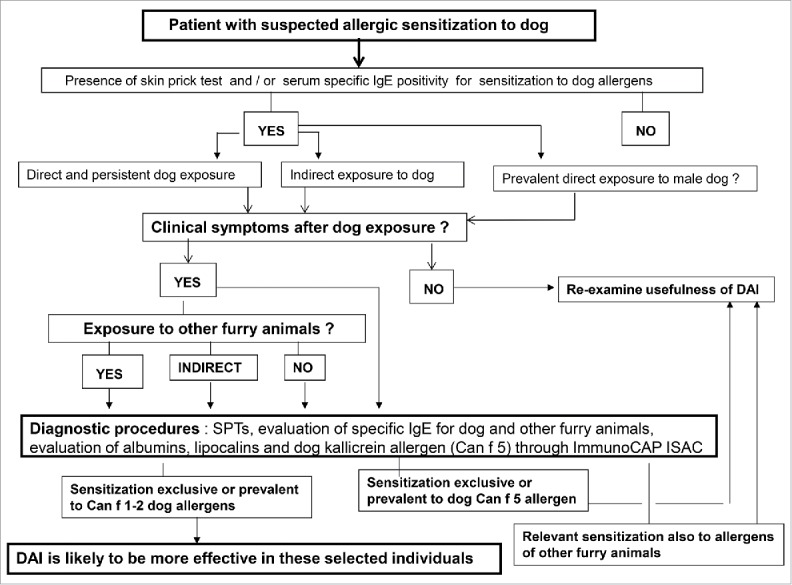

Based on our clinical and scientific experience, we would underline the need of collecting detailed information on the possible exposures to furry animals (other than the common pets), an information that usually is neglected in clinical practice. Furthermore, a detailed clinical history exploring the real significance of dog sensitization (mono or poly-sensitization, induction of clinical symptoms after exposure etc.) should be performed before prescribing DAI. In some patients, with potential high susceptibility to animal allergens, the use of CRD is essential to verify the presence of concomitant allergic sensitization to lipocalins and/or albumins belonging to other furry animals. The availability of CRD introduced the possibility of a better targeted prescription of DAI because it might be useful for point out the primary allergens and for the exclusion of cross-reactive ones. Finally, in Figure 1, we propose a flow chart to select individuals with higher possibility of positive clinical responses to DAI.

Figure 1.

Suggested flow chart to select individuals with higher possibility of positive response to DAI.

Summary statement

Some important issues might explain the frequent poor clinical results following the use of DAI in clinical practice.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and that the study has been carried out without any financial support.

Acknowledgments

We thank the veterinarian doctor Dr. Giovanni Menna as pet consultant and the biologist Dr. Romina D'Angelo for technical assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Authorship: All authors contributed equally in the writing and revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Virtanen T. Immunotherapy for pet allergies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017 Nov 28:1–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1409315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asarnoj A, Hamsten C, Wadén K, Lupinek C, Andersson N, Kull I Curin M, Anto J, Bousquet J, Valenta R et al. Sensitization to cat and dog allergen molecules in childhood and prediction of symptoms of cat and dog allergy in adolescence: A BAMSE/MeDALL study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:813–21 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.052. PMID:26686472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipocalins Hilger C. In: Matricardi PM, Kleine-Tebbe J, Hoffmann HJ, Valenta R, Ollert M, editors EAACI Molecular Allergology User's Guide. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons A/S; 2016. pages 345–52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Calzetta L, Pignatti P, Rogliani P. Can pet keeping be considered the only criterion of exposure to cat/dog allergens in the first year of life? Allergol Immunopathol (Madrid). 2016;44:387–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Cecchi L, D'Amato M, D'Amato G. Is cat keeping the main determinant of new-onset adulthood cat sensitization? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1689–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.052. PMID:22498106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Calzetta L, Piccolo A, Rogliani P. Assessment of pet exposure by questionnaires in epidemiological studies (but also in clinical practice!): why the questions should be simplified? J Asthma. 2016;53:879–81. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2016.1174260. PMID:27336848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Calzetta L, Piccolo A, Menna G, Rogliani P. Can the presence of cat/dog at home be considered the only criterion of exposure to cat/dog allergens? A likely underestimated bias in clinical practice and in large epidemiological studies. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;48:61–64. PMID:26934742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Calzetta L, Pignatti P, Rogliani P. Can pet keeping be considered the only criterion of exposure to cat/dog allergens in the first year of life? Allergol Immunopathol (Madrid). 2016;44:387–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Amato G, Liccardi G, Russo M, Barber D, D'Amato M, Carreira J. Clothing is a carrier of cat allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:577–8. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(97)70088-5. PMID:9111506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liccardi G, Barber D, Russo M, D'Amato M, D'Amato G. Human hair: an unexpected source of cat allergen exposure. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;137:141–4. doi: 10.1159/000085793. PMID:15897670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munir AKM, Einarsson R, Schou C, Dreborg SKG. Allergens in school dust.I. The amount of the major cat (Fel d 1) and dog (Can f 1) allergens in dust from Swedishschools is high enough to probably cause perennial symptoms in most children with asthma who are sensitized to cat and dog. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;91:1067–74. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90221-Z. PMID:8491939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liccardi G, Triggiani M, PiccoloA Salzillo A, Parente R, Manzi F, Vatrella A. Sensitization to common and un common pets or furry animals: which may be common mechanisms? Transl Med UniSa. 2016;14:9–14. PMID:27326390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Piccolo A, Russo M, D'Amato G. Sensitization to furry animals in an urban atopic population living in Naples, Italy. Allergy. 2011;66:1500–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02675.x. PMID:21790648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hentges F, Leonard C, Arumugan K, Hilger C. Immune response to mammalian allergens. Front Immunol. 2014 May 21;5:234 eCollection 2014 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liccardi G, Asero R, D'Amato M, D'Amato G. Role of sensitization to mammalian serum albumin in allergic disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:421–6. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0214-7. PMID:21809117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liccardi G, Passalacqua G, Salzillo A, Piccolo A, Falagiani P, Russo M, D'Amato G. Is sensitization to furry animals an independent allergic phenotype in non-occupationally exposed individuals? J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21:137–41. PMID:21462804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liccardi G, Meriggi A, Russo M, Croce S, Salzillo A, Pignatti P. The risk of sensitization to furry animals in patients already sensitized to cat/dog: A in vitro evaluation using molecular-based allergy diagnostics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1664–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.021. PMID:26051955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Calzetta L, Ora J, Rogliani P. Dog allergen immunotherapy and allergy to furry animals. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:590. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.007. PMID:27264567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinzerling LM, Burbach GJ, Edenharten G, Bachert C, Bindslev-jensen C, Bonini S. et al. GA2LE harmonization of skin prick testing: novel sensitization patterns for inhalant allergens in Europe. Allergy. 2009;64:1498–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02093.x. PMID:19772515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruchalla RS, Pougracic J, Plant M, Evans R, Visness CM, Walter M, Crain E, Kattan M, Morgan WJ, Steinbach S. Inner City Asthma Study: Relationship among sensitivity, allergen exposure, and asthma morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.006. PMID:15753892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattsson L, Lundgren T, Everberg H, Larsson H, Lidholm J. Prostatic kallikrein: A new major dog allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:362–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.021. PMID:19135239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basagaña M, Luengo O, Labrador M, Garriga T, Mattsson L, Lidholm J, et al. Component-Resolved Diagnosis of dog allergy. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2017;27:185–187 doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0150. PMID:28570224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liccardi G, Calzetta L, Salzillo A, Apicella G, Di Maro E, Rogliani P. What could be the role of Can f 5 allergen in dog-sensitized patients in “real life”? J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2017;27:397–398. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0189. PMID:29199970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jutel M, Agache I, Bonini S. et al. International consensus on allergy immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:556–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.047. PMID:26162571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith DM, Coop CA. Dog allergen immunotherapy: Past, present and future. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116:188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.12.006. PMID:26774974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liccardi G, Calzetta L, Salzillo A, Apicella G, Piccolo A, Di Maro E, Rogliani P. Dog allergy: can a prevalent or exclusive sensitization to Can f 5 be considered a lucky or negative event in “real life”?. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]; PMID:29384112; doi: 10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canonica GW, Bachert C, Hellings P. et al. Allergen Immunotherapy (AIT): A prototype of precision medicine. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8:31. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0079-7. PMID:26594303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liccardi G, Bilò MB, Manzi F, Piccolo A, Di Maro E, Salzillo A. What could be the role of molecular-based allergy diagnostics in detecting the risk of developing allergic sensitization to furry animals? Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;47:163–37. PMID:26357003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uriarte SA, Sastre J. Clinical relevance of molecular diagnosis in pet allergy. Allergy. 2016;71:1066–8. doi: 10.1111/all.12917. PMID:27108666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liccardi G, Calzetta L, Salzillo A, Billeri L, Lucà G, Rogliani P. Can dog allergen immunotherapy reduce concomitant allergic sensitization to other furry animals? A preliminary experience. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;49:92–96. PMID:28294591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoos AM, Bønnelykke K, Chawes BL, Stokholm J, Bisgaard H, Kristensen B. Precision allergy: Separate allergies to male and female dogs. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1754–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.028. PMID:28499775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basagaña M, Bartolome B, Pastor-Vargas C, Mattsson L, Lidholm J, Labrador-Horrillo M. Involvement of Can f 5 in a case of human seminal plasma allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;159:143–6. doi: 10.1159/000336388. PMID:22653399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kofler L, Kofler H, Mattsson L, Lidholm J. A case of dog-related human seminal plasma allergy. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;44:89–92. PMID:22768730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liccardi G, Caminati M, Senna GE, Calzetta L, Rogliani P. Anaphylaxis and intimate behaviour. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17:350–355. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000386. PMID:28742538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]