Abstract

PURPOSE

Many who seek primary health care advice about mental health may be using mobile applications (apps) claiming to improve well-being or relieve symptoms. We aimed to identify how prominent mental health apps frame mental health, including who has problems and how they should be managed.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative content analysis of advertising material for mental health apps found online in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia during late 2016. Apps were included if they explicitly referenced mental health diagnoses or symptoms and offered diagnosis and guidance, or made health claims. Two independent coders analyzed app store descriptions and linked websites using a structured, open-ended instrument. We conducted interpretive analysis to identify key themes and the range of messages.

RESULTS

We identified 61 mental health apps: 34 addressed predominantly anxiety, panic, and stress (56%), 16 addressed mood disorders (26%), and 11 addressed well-being or other mental health issues (18%). Apps described mental health problems as being psychological symptoms, a risk state, or lack of life achievements. Mental health problems were framed as present in everyone, but everyone was represented as employed, white, and in a family. Explanations about mental health focused on abnormal responses to mild triggers, with minimal acknowledgment of external stressors. Therapeutic strategies included relaxation, cognitive guidance, and self-monitoring. Apps encouraged frequent use and promoted personal responsibility for improvement.

CONCLUSIONS

Mental health apps may promote medicalization of normal mental states and imply individual responsibility for mental well-being. Within the health care clinician-patient relationship, such messages should be challenged, where appropriate, to prevent overdiagnosis and ensure supportive health care where needed.

Key words: mobile health, mHealth, qualitative research, mental health, medicalization

INTRODUCTION

There are thousands of commercially available, mobile applications (apps) for mental health, which are hugely popular with the public.1 When persons with mental distress seek assistance from health care practitioners, it is likely that many of them will already be using mental health apps.2,3

Mental health apps offer tools for self-diagnosis, monitoring, symptom management, and treatment.4,5 A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of apps for depression found that app users experienced a decrease in their depressive symptoms,6 although others found that computerized cognitive behavioral therapy offers no additional benefit beyond usual clinician care.7 Importantly, the few scientifically evaluated apps are often unavailable to the public, and evidence for efficacy other than for depression remains limited. Nevertheless, apps are likely to shape public perceptions about mental illnesses and symptom management.8–10

Given the enthusiasm for mental health apps shown by governments, health services, and the public,1,11–14 it seems timely to analyze app advertising critically to identify and evaluate the kinds of messages about mental health they contain. We conducted a qualitative content analysis of mental health messages guided by the following research questions: (1) How do prominent mental health apps frame mental health and illness? (2) What does this framing suggest about the pattern and causation of mental health problems and how problems can be managed?

METHODS

We conducted a critical, interpretive qualitative content analysis of prominent mobile mental health apps in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia to understand their social, cultural, and political dimensions.10 The research team included mental health clinicians, qualitative researchers, and representatives of a consumer advocacy organization.5

Sampling

App stores differ by country; their search algorithms are proprietary, personalized, and localized; and the population of apps changes rapidly.15 We identified widely promoted mental health apps from August 18 to September 9, 2016, using (1) an app store application programing interface crawling program identifying apps persisting in the top 100 of Health and Fitness and Medical store categories in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia; and (2) government, health, or media endorsements (Supplemental Appendix, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/4/338/suppl/DC1/).

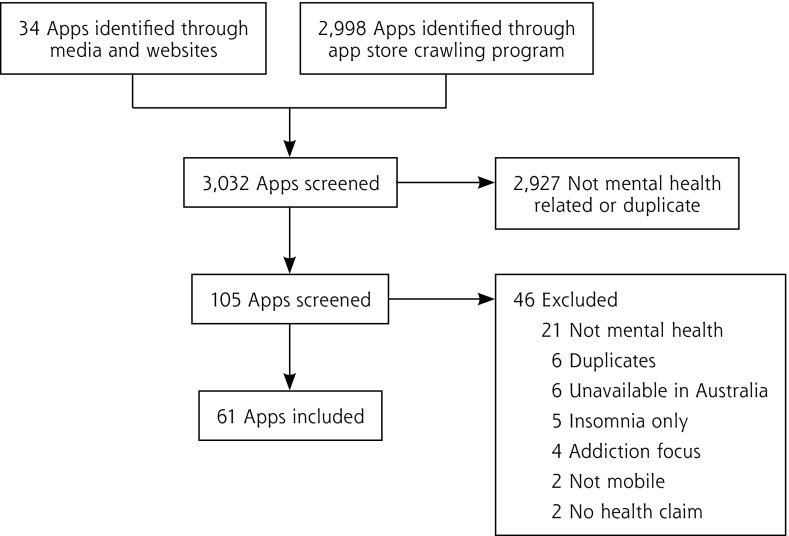

Figure 1 details the screening process. Two researchers independently screened 105 apps for inclusion according to the following criteria: the apps (1) were designed for a mobile platform; (2) they were available in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, or Australia; (3) and the advertising materials were in English describing mental health explicitly as it pertained to a mental health diagnosis (eg, depression), a mental health symptom (eg, suicidality), or behaviors related to mental health (eg, meditation, mindfulness), and provided diagnosis, guidance, or a recommendation; allowed for monitoring or tracking of user-generated data; or made a mental health claim.

Figure 1.

Mental health app screening and selection process.

App = mobile application.

Reproduced with permission from: Grundy.5

We excluded apps relating exclusively to addiction, although this topic is important for future study.

Data Collection

We collected data from apps’ advertising materials, including app store descriptors and linked websites. These materials have the same format and content for all prospective users, unlike downloaded app content, which is frequently personalized. We developed an open-ended data collection form based upon Lupton’s critical approach to studying apps (Supplemental Table 1, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/4/338/suppl/DC1/),10 focusing on messages and claims about mental health. Two researchers extracted data independently. All authors discussed and resolved any discrepancies within a team workshop.

Data Analysis

We inductively coded the open-ended responses using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd), wrote interpretive memos on each code, and generated a preliminary list of themes. The research team reviewed emerging themes.16,17 We used framing theory9 to develop these themes into interpretive memos.

RESULTS

We identified 61 mental health apps (Supplemental Table 2, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/4/338/suppl/DC1/): 40 (66%) through the crawling program, and 23 (38%) from media reports and websites (2 apps were identified by both search strategies). The 61 apps were published by 45 unique developers, 17 (38%) being private companies, and 23 (51%) based in North America. Of the 61 apps, 36 (59%) were freely available, although 48 (79%) offered in-app purchases. Thirty-five apps (56%) claimed to reduce anxiety, panic, and stress, and 16 (26%) claimed to benefit those with mood disorders. The remaining 11 (18%) focused on well-being or other mental health issues (eg, anger management, eating disorders). Within the sampled apps’ advertising materials, we identified a range of messages about mental health.

Defining the Problem

Apps advertising materials framed mental health problems in 1 or more of 3 main ways (Table 1). The most dominant frame portrayed mental health problems conventionally in terms of psychological states.

Table 1.

Framing of Mental Health Problems in Advertising Material of Mental Health Apps

| Apps’ framing materials claimed a mental health problem exists when… |

| One has a psychological issue, such as distressing symptoms (eg, anxiety, depression, panic, poor sleep) and/or lack of positive psychological states (eg, happiness, balance) |

| One is at risk of having a psychological issue that is due to a lack of mental fitness |

| One’s life lacks some external feature of success (eg, academic or relationship success) |

App = mobile application.

Epidemiology of and Management of Mental Health Problems

App materials delivered a strong message that mental health problems existed for everybody (Table 2). Screenshots and descriptions, however, tended to represent everyone as employed, white, and in a family. For example, Calm Down Now highlighted the “every-targeted niche populations, such as military veterans or persons with diagnosed mental illnesses.

Table 2.

Dominant Messages About Epidemiology and Management of Mental Health Problems

| Characteristic | Message and App |

|---|---|

| Population: everybody | “[A]ll kinds of people who, in certain situations, or in certain periods of life are: feeling stressed; need motivation and lack energy; people with mild mental distress, such as depressive disorders, anxiety, stress, and low self-esteem.” Mindfit |

| Causation | |

| Pathophysiology | “The fight or flight response…can easily go into hyperdrive, making you feel uncomfortable and anxious even when you aren’t in any real danger.” Mindfulness: Brain-based |

| Psychological maladaptation | “[H]abits of thought and behaviors that are negatively impactful.” Mindfulness Daily |

| Apps and management | |

| Easy, effective, no risk of harm | “All you have to do is LISTEN and your brain will do the rest!” Anxiety Release based on EMDR |

| Importance of regular, ongoing use | “You can…fit several mini-sessions into your day.” Meditation Studio |

| Personal responsibility for improvement | “Take action to improve your life.” MoodKit – Mood Improvement Tools |

App = mobile application; EMDR = eye movement desensitization and reprocessing.

App materials attributed mental health problems to abnormal neurophysiology that could produce problems after a minor trigger or to unhelpful psychological habits (Table 2). Only a few apps implied mental health symptoms might be a normal reaction to external stress.

The 61 apps offered 1 or more of 3 therapeutic modalities: 30 (49%) offered calming (eg, mindfulness), 24 (39%) offered cognitive therapies (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy), and 13 (21%) offered track/share/compare tools (eg, self-monitoring).

Many apps, 37 (61%), claimed vague scientific authority for their approach, such as “clinically proven” (Breathing Zone). Two apps mentioned formal studies of their own products, which were not cited.

App materials claimed their product could help quickly and easily, although some acknowledged that they might not cure. Many descriptors used moral language to prompt use, such as, “if you are serious about managing your anxiety then you can do it yourself using the techniques in this app” (Self-help Anxiety Management). In contradiction to the message about ease of use, many apps required frequent user action to deliver results (Table 2).

Thirty apps (49%) provided disclaimers absolving themselves of responsibility. For example, “We give no representation or warranties about the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose [of our] advice” (Pacifica). Thus, app consumers were assigned responsibility not only for using an app, but also for knowing whether it was appropriate for them.

DISCUSSION

We identified 2 dominant messages about mental health: (1) poor or fragile mental health is ubiquitous, and (2) individuals can easily manage their own mental health problems with apps. Developers offered very limited scientific evidence for the apps’ claimed benefits.

These messages echo (but also potentially drive) a tendency toward medicalization, whereby normal life becomes under the purview of clinical care.18,19 The idea of mental health care for everyone might help reduce stigma, but arguably at the cost of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Diagnosing mild or temporary symptoms as illness, where that diagnosis brings no patient benefit, is problematic. It can lead to unnecessary treatment and divert resources from those who really need help.20,21 Further, the lack of diversity in representation of users and stressors may alienate persons with serious needs.

Apps enable people to attend to their own health, but at the same time they promote the idea that individuals should take personal responsibility for their own health. App-based treatments may suit many consumers, but the ability of apps to enable frequent self-monitoring and therapy may transform into a moral imperative that we should all be undertaking these activities.8,22 The associated silence around external factors constitutes a denial of the social determinants of health.23

Implications for Research and Practice

We encourage health care professionals to ask patients about app use and initiate discussions about the messages we have highlighted in this study. Patients may benefit from hearing alternative views about what constitutes normal psychological experiences, with specific attention toward counteracting medicalization. Mental health apps may appear compelling, but the idea that we all need or should engage in frequent app use should not be taken too seriously. Importantly, apps may deliver time burdens or loss of privacy to the app user.14,24 In addition, patients may benefit from discussion about the limitations of app use and be encouraged to seek clinical attention for important or enduring psychological distress.

Limitations

Our content analysis was restricted to app advertising materials. Consumers access this information when choosing apps, however, so it constitutes a major source of mental health messages. Our qualitative content analysis relied upon a purposive sample of prominent mental health apps and is not representative, but consumers are likely to encounter these targeted apps. The population of apps is highly dynamic, thus apps included in this study may no longer be available and their content may have been updated. Finally, consumers do not necessarily use apps as directed, and some app users may be unaffected by the messages we describe here.

Apps are important vehicles of information about health that may reflect and shape societal views. Many apps medicalize normal mental states and present normative messages about personal responsibility for well-being. Physicians should counterbalance these messages where necessary to ensure that self-help is just one aspect of a supportive climate for mental health care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chris Klochek, MS, for developing the app store crawling programs.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This work was funded by a research grant from the Australian Communications Consumer Action Network (ACCAN). The operation of the Australian Communications Consumer Action Network is made possible by funding provided by the Commonwealth of Australia under section 593 of the Telecommunications Act 1997. This funding is received from charges on telecommunications carriers. The project was encouraged and supported by ACCAN, who worked with the researchers throughout the design and dissemination of the study to facilitate research translation.

Disclaimer: The researchers had full autonomy over study design, data collection, analysis, and publication.

Supplementary materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/16/4/338/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J, Clarke J, Birch MR, Christensen H. Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013; 15(11): e247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding C, Ilves P, Wilson S. Digital mental health services in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2015; 65(631): 58–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubanovich CK, Mohr DC, Schueller SM. Health app use among individuals with symptoms of depression and anxiety: a survey study with thematic coding. JMIR Ment Health. 2017; 4(2): e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olla P, Shimskey C. mHealth taxonomy: a literature survey of mobile health applications. Health Technol. 2015; 4(4): 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy Q, Parker L, Raven M, Gillies D, Mintzes B, Bero L. Finding Peace of Mind: Navigating the Marketplace of Mental Health Apps. Sydney, Australia: Australian Communications Consumer Action Network; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firth J, Torous J, Nicholas J, et al. The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2017; 16(3): 287–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbody S, Littlewood E, Hewitt C, et al. ; REEACT Team. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015; 351: h5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronowitz R. Framing disease: an underappreciated mechanism for the social patterning of health. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 67(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Entman RM. Framing: towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 1993; 43(4): 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lupton D. Apps as artefacts: towards a critical perspective on mobile health and medical apps. Societies (Basel). 2014; 4(4): 606–622. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization (WHO). Mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva, Switzlerland: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Australian Government. Australian Government response to Contributing Lives, Thriving Communities - Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen H, Petrie K. State of the e-mental health field in Australia: where are we now?. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013; 47(2): 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollis C, Morriss R, Martin J, et al. Technological innovations in mental healthcare: harnessing the digital revolution. Br J Psychiatry. 2015; 206(4): 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundy QH, Wang Z, Bero LA. Challenges in assessing mobile health app quality: a systematic review of prevalent and innovative methods. Am J Prev Med. 2016; 51(6): 1051–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason J. Qualitative Researching. 2nd ed. London, UK: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis.London, UK: SAGE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.White K. An Introduction to the Sociology of Health and Illness. 2nd ed. London, UK: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. The Loss Of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow Into Depressive Disorder. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frances A. Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-Of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life. New York, NY: William Morrow; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowrick C, Frances A. Medicalising unhappiness: new classification of depression risks more patients being put on drug treatment from which they will not benefit. BMJ. 2013; 347: f7140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lupton D. Femininity, responsibility, and the technological imperative: discourses on breast cancer in the Australian press. Int J Health Serv. 1994; 24(1): 73–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blaxter M. Why do the victims blame themselves? In: Bury M, Gabe J, eds. The Sociology of Health and Illness - A Reader. London, UK: Routledge; 2004: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye K. FTC: Fitness apps can help you shred calories - and privacy. Advert Age. http://adage.com/article/privacy-and-regulation/ftc-signals-focus-health-fitness-data-privacy/293080/. Published May 7, 2014.