Abstract

BACKGROUND

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) has emerged as a new avenue of interest due to its various biological functions in cancer. Abnormal expression of lncRNA has been reported in other malignancies but has been understudied in head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC).

METHODS

lncRNA expression was interrogated via qRT-PCR array for 19 HPV-negative HNSCC tumor-normal pairs. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was used to validate these results. The association between differentially expressed lncRNA and survival outcomes was analyzed.

RESULTS

Differential expression was validated for 5 lncRNA (SPRY4-IT1, HEIH, LUCAT1, LINC00152, and HAND2-AS1). There was also an inverse association between MEG3 expression (not significantly differentially expressed in TCGA tumors but highly variable expression) and 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS).

CONCLUSION

We identified and validated differential expression of 5 lncRNA in HPV-negative HNSCC. Low MEG3 expression was associated with favorable 3-year RFS, although the significance of this finding remains unclear.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, HNSCC, lncRNA, ncRNA, TCGA, survival

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common cancer type worldwide and accounts for approximately 350,000 deaths per year(1, 2). Risk factors such as tobacco, alcohol use, and more recently, human papilloma virus (HPV) have been identified as etiological factors in the occurrence of HNSCC. Despite advances in the treatment of localized HNSCC, approximately half of patients will develop recurrent disease(3), which is a major contributor to patient mortality. In addition, HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC are biologically distinct with the latter being associated with poorer prognosis. Unlike other malignancies, there are no tools in widespread use that can identify early disease and there is no systematic approach that has proven effective in monitoring for early evidence of recurrence. Hence, novel markers are needed that appropriately characterize those patients with early stage disease as well as identify and characterize the response of individual patient’s treatment.

While only 1.2% of our DNA sequence encodes proteins, approximately 75% of the human genome is capable of being transcribed into RNA(4), and it has become increasingly apparent that RNA plays a diverse and important role in genome integrity through production of both proteins as well as non-coding RNA (ncRNA), including long non-coding RNA (lncRNA). While the microRNA (miRNA) class of ncRNA have been widely studied in the context of cancer, lncRNA, which are larger (> 200 bases and ~1-2 exons in length)(5) and have a more complex secondary/tertiary structure, have recently begun to garner increased attention(6). This is largely due to their diverse biological functions(7), which can include inhibition of target gene transcription, initiation of alternative splicing, generation of protein scaffolding and chromatin organization, and alteration of transcription factor activity.

Even though 18,000 human long non-coding human transcripts have been catalogued in GENCODE v7(4), the lncRNA Database (http://www.lncrnadb.org), a database of functionally annotated eukaryotic lncRNA, only contains information for 127 human lncRNA, highlighting the gap in our knowledge of lncRNA biology. Identification of lncRNA transcripts that are associated with human diseases and the corresponding pathobiology (e.g. aggressiveness or responsiveness to treatment) would therefore provide a welcome means for prioritizing functional studies.

Several lncRNA have recently been reported to be differentially expressed in various cancers and to play a role in cancer growth, invasion, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, motility, and metastatic potential(8, 9), and as such are increasingly being recognized as having a very strong potential as cancer biomarkers(10). Several recent studies have reported that higher expression of lncRNA, such as HOTAIR (HOX antisense intergenic RNA) and Malat-1 (metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1), is associated with invasion and metastasis in various epithelial cancers(11-17), although the prognostic significance of lncRNA in HNSCC has been understudied to date. The aim of this study was to identify differentially expressed lncRNA in HPV-negative HNSCC and assess its impact on outcomes in these groups of patients.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Tumor Samples

Initial identification of differentially expressed lncRNA in HPV-negative HNSCC was conducted using a quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) array consisting of 84 lncRNA with reported involvement in various cancers using paired archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue and paired adjacent normal squamous tissue from 19 patients treated for incident HNSCC at the University of Cincinnati Cancer Institute. Raw RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) reads for all available HPV-negative head and neck cancer tumors (n = 444) and all available adjacent normal tissue (n = 44) was downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for independent validation of significant results.

RT2 lncRNA qPCR Cancer Array

Total RNA was extracted from each sample using the RNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and converted to cDNA using the RT2 First Strand kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s respective suggested protocols. The RT2 Profiler lncRNA qPCR Cancer PathwayFinderArray (96-well format) was used to profile expression of 84 lncRNA transcripts that have been associated with various cancer types. The array also contains 3 reverse transcription controls, 3 positive PCR controls, a probe for human gDNA contamination, and 5 housekeeping genes for normalization: beta actin (ACTB); beta-2 microglobulin (B2M); Ribosomal protein, large, P0 (RPLP0); 7SK small nuclear RNA (RN7SK); and Small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 73A (SNORA73A). PCR mastermix was prepared with 250ng of total cDNA and dispensed in 24μl aliquots into each RT2 lncRNA PCR Array well. RT-qPCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) under the following conditions: 10 min at 95°C using HotStart Taq Polymerase followed by 40 cycles of 15s at 95°C and 1min at 60°C. A complete list of the 84 lncRNA included on the array can be found in Supplemental Table S1.

Differential Expression

Expression was normalized to the geometric mean of 5 housekeeping control genes: beta actin (ACTB); beta-2 microglobulin (B2M); Ribosomal protein, large, P0 (RPLP0); 7SK small nuclear RNA (RN7SK); and Small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 73A (SNORA73A). Differential expression of each lncRNA was described in terms of fold-change for tumor relative to adjacent normal tissue based on a one-sample t-test, adjusted for multiple testing by false discovery rate (FDR) estimation and Q values using the methods proposed by Benjamini & Hochberg (53). Expression was considered significantly differential where Q ≤ 0.10.

Replication Using TCGA RNA-Sequencing Data

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data in the form of bam files of aligned reads was obtained for head and neck cancers in TCGA project where downloaded from the Cancer Genomics Hub. Reads not mapped to human genome where aligned to HPV (NC_001526) E6 and E7 viral oncoproteins using bowtie aligner(18). HPV-status was inferred by designating the sample to be from a HPV-positive tumor if more than 1,000 reads mapped to HPV oncoproteins and HPV-negative tumor otherwise. The harmonized read counts for head and neck TCGA samples aligned to lncRNA defined in the GDC.h38 GENCODE v22 GTF file were downloaded from NCI Genomic Data Commons(19) using the TCGAbiolinks Bioconductor package(20).

Normalized counts (count per million) for each of the 7 lncRNA in each sample were calculated using the cpm function in the Bioconductor package edgeR(21). Since the distributions of lncRNA expression were non-linear, differential expression was assessed non-parametrically, using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, comparing tumor expression (n = 444) to that of all available normal samples (n = 44), and was considered differential where p ≤ 0.05. Median fold-change was determined for each tumor by comparing its expression to the median expression of the normal samples. A description of the distribution of expression values for the 7 lncRNA in the 44 adjacent normal samples is provided in Supplemental Table S2.

Survival Analysis Using TCGA Samples

To visualize 5-year overall survival (OS) and 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS), univariate Kaplan-Meier and cumulative incidence (to account for death as a competing risk(22, 23)) functions were generated, respectively, comparing curves for low, normal, and high expression levels. Discrete multivariable Cox proportional hazards and cumulative incidence models were fit to assess 5-year OS and 3-year RFS, respectively, for each of the significant lncRNA, adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, tumor site, and stage at diagnosis, as established a priori. Missing values of model covariates were imputed (m = 20) using multivariate normal regression, based on age, sex, stage, and primary tumor site. Log-log plots [i.e. -log(-log (S(t))) vs. log(t)] were generated for each model to verify that the proportional hazards assumption was met. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was considered when the unadjusted p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

The median age for the UC cases (n = 19 tumor-normal pairs) was 64 years, 74% of which were male. UC and TCGA sets differed in terms of smoking status (p = 0.01), with fewer non-smokers in the UC set, but were comparable in terms of age, sex, race, primary tumor site, AJCC stage group, and tumor grade (Table 1). The majority of tumors in both sets originated in the oral cavity (63% and 66%, respectively), and presented at an advanced stage (III or IV).

Table 1.

Clinicodemographic characteristics of HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cases from the University of Cincinnati and TCGA validation set.

| University of Cincinnati (n = 19) | TCGA Validation Set (n = 444) | pdifference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.28a | ||

| Years, median (range) | 64 (51-86) | 61.5 (19-90) | |

| Sex | 0.83b | ||

| Male | 14 (74%) | 317 (71%) | |

| Female | 5 (26%) | 127 (29%) | |

| Race | 0.44b | ||

| White | 16 (84%) | 355 (83%) | |

| Black | 3 (16%) | 44 (10%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 30 (7%) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.01b | ||

| Never | 1 (5%) | 93 (21%) | |

| Former | 15 (79%) | 181 (42%) | |

| Current | 3 (16%) | 160 (37%) | |

| Primary Tumor Site | 0.75b | ||

| Oral cavity | 12 (63%) | 294 (66%) | |

| Pharynx | 1 (5%) | 41 (9%) | |

| Larynx | 6 (32%) | 109 (25%) | |

| AJCC Stage Group | 0.68b | ||

| I | 0 (0%) | 23 (5%) | |

| II | 2 (11%) | 74 (17%) | |

| III | 5 (28%) | 82 (18%) | |

| IV | 11 (61%) | 265 (60%) | |

| Tumor Grade | 0.25b | ||

| Well differentiated | 6 (32%) | 59 (13%) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 9 (47%) | 276 (63%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 4 (21%) | 96 (22%) | |

| Undifferentiated | 0 (0%) | 2 (<1%) | |

| Undetermined | 0 (0%) | 8 (2%) |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum test

Fisher’s Exact test

Abbreviations: TCGA = The Cancer Genome Atlas; AJCC = Americal Joint Committee on Cancer hrHPV = high-risk human papillomavirus

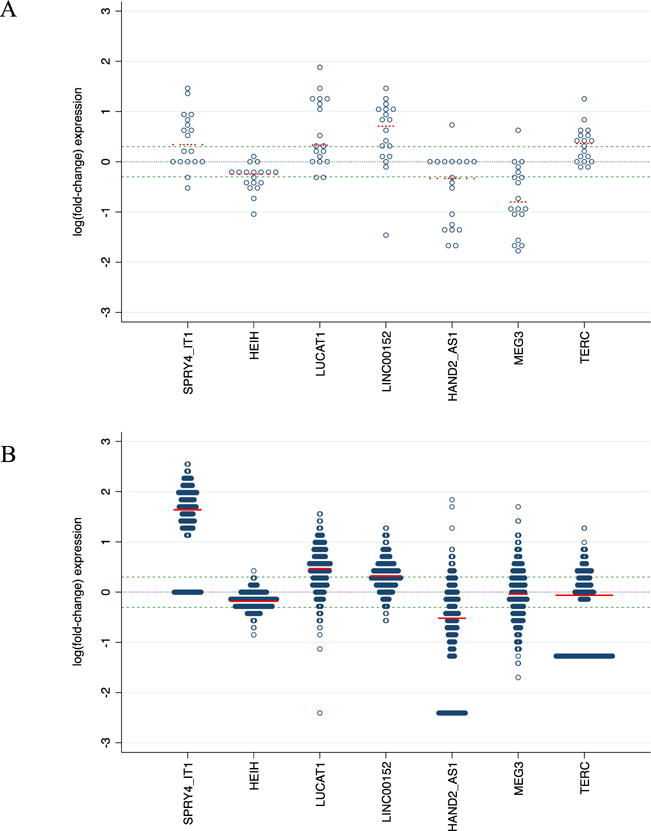

Eleven of the lncRNA included on the array were not detected in any of the tumor or normal samples (Supplemental Table S1). Twenty lncRNA were significantly differentially expressed at a nominal p-value ≤ 0.05 (8 upregulated, 12 downregulated). After FDR adjustment, 7 lncRNA remained significantly differential (Q ≤ 0.10: SPRY4-IT1, HEIH, LUCAT1, LINC00152, and HAND2-AS1, MEG3 and TERC; 4 upregulated, 3 downregulated; Table 2). Expression of these 7 lncRNA was also significantly differential for 5 of the 7 lncRNA in the TCGA validation set (SPRY4-IT1, HEIH, LUCAT1, LINC00152, and HAND2-AS1). It should be noted, however, that although MEG3 and TERC were not significantly differentially expressed in the TCGA validation set, there was wide variability in terms of expression in both directions (i.e. upregulation and downregulation) for individual tumors relative adjacent normal samples (Figure 1B). Interestingly, Black patients in the TCGA dataset were significantly more likely to exhibit high (> 2-fold) and low (< 0.5-fold) MEG3 expression (Table 3).

Table 2.

Differentially expressed lncRNA in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

| Human lncRNA qPCR Cancer Array (nT-N pairs = 19) |

TCGA RNA-seq Replication Set (n = 444) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lncRNA | Ensembl ID | Median Fold-Change | p-value | Q-value | Median Fold-Change | p-value |

| SPRY4-IT1 | ENSG00000281881 | 2.19 | 0.006 | 0.07 | 3.52 | < 0.0001 |

| HEIH | ENSG00000278970 | 0.56 | 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.64 | < 0.0001 |

| LUCAT1 | ENSG00000248323 | 2.14 | 0.002 | 0.04 | 1.76 | < 0.0001 |

| LINC00152 | ENSG00000222041 | 5.11 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 1.56 | < 0.0001 |

| HAND2-AS1 | ENSG00000237125 | 0.47 | 0.005 | 0.06 | 0.13 | < 0.0001 |

| MEG3 | ENSG00000214548 | 0.16 | 0.0003 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.50 |

| TERC | ENSG00000270141 | 2.32 | 0.0007 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.12 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of log(fold-change) in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) tumors relative to adjacent non-malignant squamous tissue for (A) University of Cincinnati patients (n = 19 tumor-normal pairs) and (B) HPV-negative tumors (n = 444) and adjacent normal tissue (n = 44) with RNA-sequencing data through The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The black dashed center line at 0 corresponds to neutral expression and blue dashed lines above and below the center line correspond to respective fold changes of 2.0 and 0.5 respectively; mean log(fold-change) for each lncRNA is denoted by a red dashed line.

Fold-change for the 19 tumors samples in panel A was calculated by comparing the expression of each tumor to its paired adjacent normal sample; fold-change for the 444 TCGA tumors in panel B was calculated by comparing the expression to the median expression of the 44 adjacent normal TCGA samples.

Table 3.

Association between expression of significantly differential lncRNA and patients characteristics and clinical features in the TCGA HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) samples (n = 444).

| SPRY4-IT1 | HEIH | LUCAT1 | LINC00152 | HAND2-AS1 | MEG3 | TERC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| N = 444 | Low (n = 89) |

High (n = 0) |

Low (n = 92) |

High (n = 2) |

Low (n = 19) |

High (n = 291) |

Low (n = 6) |

High (n = 291) |

Low (n = 275) |

High (n = 43) |

Low (n = 134) |

High (n = 107) |

Low (n = 189) |

High (n = 99) |

| Age, per decade | 1.08 (0.87-1.34) | — | 0.75 (0.60-0.94) | — | 1.11 (0.65-1.88) | 0.99 (0.82-1.21) | — | 1.09 (0.83-1.43) | 0.87 (0.70-1.08) | 0.67 (0.48-0.92) | 0.84 (0.68-1.04) | 0.93 (0.74-1.16) | 1.05 (0.86-1.28) | 1.40 (1.08-1.81) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 0.72 (0.41-1.26) | — | 0.56 (0.30-1.06) | — | 0.60 (0.15-2.44) | 1.07 (0.64-1.78) | — | 0.90 (0.46-1.77) | 0.60 (0.35-1.01) | 0.62 (0.26-1.47) | 1.45 (0.84-2.50) | 1.00 (0.55-1.81) | 1.36 (0.81-2.30) | 0.65 (0.33-1.28) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.26 (0.49-3.23) | — | 1.15 (0.51-2.58) | — | 0.49 (0.06-4.40) | 0.74 (0.36-1.50) | — | 0.94 (0.35-2.54) | 1.16 (0.51-2.64) | 1.57 (0.47-5.30) | 3.34(1.43-7.80) | 2.85 (1.18-6.90) | 0.90 (0.41-1.99) | 1.05 (0.43-2.57) |

| Other | 0.97 (0.37-2.58) | — | 3.50 (1.47-8.35) | — | 0.88 (0.09-8.95) | 1.41 (0.54-3.68) | — | 0.81 (0.28-2.38) | 0.90 (0.37-2.23) | — | 0.74 (0.29-1.86) | 0.41 (0.13-1.30) | 0.85 (0.35-2.09) | 1.00 (0.34-2.98) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Former | 1.27 (0.65-2.45) | — | 1.12 (0.53-2.38) | — | 0.73 (0.19-2.83) | 0.67 (0.36-1.26) | — | 0.60 (0.25-1.43) | 0.59 (0.45-1.72) | 0.54 (0.20-1.47) | 1.64 (0.84-3.22) | 0.68 (0.35-1.34) | 1.57 (0.84-2.90) | 1.59 (0.73-3.50) |

| Current | 1.59 (0.77-3.30) | — | 1.37 (0.65-2.91) | — | 0.39 (0.07-2.20) | 0.79 (0.40-1.54) | — | 0.78 (0.30-2.00) | 0.59 (0.29-1.20) | 0.45 (0.16-1.24) | 0.90 (0.44-1.85) | 0.53 (0.26-1.08) | 1.48 (0.77-2.84) | 1.30 (0.56-3.03) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Primary tumor site | ||||||||||||||

| Oral cavity | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Pharynx | 1.34 (0.52-3.48) | — | 0.53 (0.19-1.47) | — | 3.20 (0.83-12.40) | 0.61 (0.28-1.29) | — | 0.36 (0.14-0.92) | 1.08 (0.49-2.40) | 0.52 (0.13-2.09) | 1.29 (0.58-2.90) | 0.92 (0.36-2.32) | 1.15 (0.50-2.64) | 1.73 (0.67-4.49) |

| Larynx | 0.82 (0.43-1.54) | — | 0.93 (0.50-1.74) | — | 1.25 (0.31-5.08) | 0.96 (0.55-1.66) | — | 0.53 (0.26-1.06) | 1.33 (0.74-2.41) | 0.48 (0.16-1.47) | 0.71 (0.39-1.30) | 0.86 (0.46-1.62) | 0.56 (0.31-1.01) | 1.49 (0.77-2.88) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| AJCC Stage Group | ||||||||||||||

| Early (I or II) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Late (III or IV) | 1.09 (0.52-2.28) | — | 0.62 (0.28-1.37) | — | 2.06 (0.42-10.13) | 1.48 (0.78-2.82) | — | 1.49 (0.65-3.42) | 2.86 (0.74-2.41) | 0.75 (0.20-2.81) | 1.11 (0.56-2.18) | 1.01 (0.48-2.14) | 1.84 (0.94-3.60) | 0.39 (0.17-0.91) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| N classification | ||||||||||||||

| N0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| N1-3 | 0.88 (0.47-1.65) | — | 1.65 (0.86-3.19) | — | 0.47 (0.13-1.71) | 0.82 (0.47-1.44) | — | 1.25 (0.59-2.63) | 0.28 (0.15-0.54) | 1.31 (0.39-4.44) | 0.49 (0.28-0.88) | 0.72 (0.38-1.34) | 0.97 (0.56-1.69) | 2.68 (1.26-5.69) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||||||||

| Low | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate | 1.39 (0.66-2.92) | — | 1.22 (0.56-2.64) | — | 1.87 (0.20-17.04) | 1.38 (0.73-2.58) | — | 1.34 (0.58-3.13) | 1.07 (0.52-2.19) | 0.74 (0.25-2.19) | 0.83 (0.41-1.66) | 1.01 (0.48-2.19) | 0.94 (0.48-1.85) | 1.17 (0.49-2.81) |

| High/undifferentiated | 0.64 (0.28-1.46) | — | 0.67 (0.26-1.72) | — | 7013 (0.78-64.74) | 1.22 (0.58-2.58) | — | 1.21 (0.45-3.28) | 0.87 (0.38-1.96) | 0.94 (0.28-3.21) | 0.65 (0.29-1.47) | 1.33 (0.31-1.85) | 0.62 (0.28-1.35) | 0.71 (0.26-1.90) |

The relationship between each of the 7 lncRNA and 5-year OS and 3-year RFS was assessed using the TCGA dataset. Amongst the 7 lncRNA identified, only differing levels of Maternally Expressed 3 (MEG3) had an impact on 3 year RFS. Patients with low MEG3 expression (<0.5 fold change) were found to have a significantly lower 3-year RFS while higher MEG3 expression (> 2 fold change) appeared to have better 3-year RFS, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2 and Table 4). We also analyzed the associations between the 7 lncRNA and clinical characteristics of HPV-negative HNSCC in the TCGA dataset and found that low MEG3 expression was associated with locally advanced disease and low expression of HANDS-2AS1 correlated with more locally advanced cancer, although this did not appear to have an impact on survival outcomes. Restriction of the differential expression analysis to the 44 tumor-normal pairs in the TCGA validation set yielded similar results (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence function for 3-year relapse-free survival of HPV-negative TCGA head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) tumors according to MEG3 expression level.

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and subhazard ratios (SHR) for the association between expression of differentially expressed lncRNA and 5-year overall survival (OS) and 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS), respectively, in patients with HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

| 5-year Overall Survival (OS) (N = 439) |

3-year Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) (N = 272) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lncRNA expression | n | Crude HR | Adjusted HRa | n | Crude SHR | Adjusted SHRa |

| SPRY4-IT1 | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 0 | — | — | 0 | — | — |

| Normalb | 87 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 54 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 352 | 0.93 (0.62-1.38) | 0.89 (0.60-1.34) | 218 | 1.40 (0.63-3.12) | 1.30 (0.54-3.13) |

| HEIH | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 92 | 0.82 (0.54-1.28) | 0.88 (0.56-1.36) | 59 | 0.91 (0.45-1.84) | 1.14 (0.54-2.40) |

| Normalb | 345 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 212 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| LUCAT1 | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 18 | 1.49 (0.67-3.32) | 1.61 (0.71-3.68) | 12 | 3.07 (0.84-11.19) | 2.58 (0.71-9.33) |

| Normalb | 131 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 80 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 290 | 0.92 (0.64-1.31) | 0.85 (0.60-1.23) | 180 | 1.50 (0.74-3.02) | 1.54 (0.70-3.41) |

| LINC00152 | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 8 | — | — | 7 | — | — |

| Normalb | 68 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 41 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 363 | 0.84 (0.55-1.28) | 0.74 (0.48-1.14) | 224 | 1.32 (0.52-3.34) | 1.11 (0.41-3.04) |

| HAND2-AS1 | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 271 | 0.92 (0.64-1.31) | 0.96 (0.66-1.39) | 167 | 0.87 (0.47-1.64) | 0.83 (0.43-1.60) |

| Normalb | 126 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 80 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 42 | 0.63 (0.30-1.34) | 0.71 (0.33-1.51) | 25 | 0.94 (0.31-2.83) | 0.82 (0.25-2.65) |

| MEG3 | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 133 | 1.09 (0.75-1.57) | 1.11 (0.76-1.62) | 71 | 0.38 (0.14-1.00) | 0.28 (0.10-0.78) |

| Normalb | 202 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 127 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 104 | 0.88 (0.56-1.40) | 0.84 (0.53-1.34) | 74 | 1.63 (0.89-2.98) | 1.43 (0.75-2.74) |

| TERC | ||||||

| Low (<0.5-fold) | 187 | 1.01 (0.69-1.47) | 0.90 (0.61-1.33) | 115 | 1.25 (0.62-2.51) | 1.30 (0.61-2.79) |

| Normalb | 155 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 97 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High (>2-fold) | 97 | 0.98 (0.62-1.54) | 0.97 (0.60-1.55) | 60 | 1.75 (0.82-3.72) | 2.24 (0.95-5.25) |

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, primary tumor site, and AJCC stage group

Tumor expression >0.5-fold and < 2-fold was considered to be within normal range

DISCUSSION

There is increasing evidence that aberrant expression of lncRNA plays a role in the genesis and progression of HNSCC(24, 25). Through our present study, we were able to identify and validate 5 differentially expressed lncRNA in HPV-negative HNSCC (SPRY4-IT1, HEIH, LUCAT1, LINC00152, and HAND2-AS1). Further, we found that low expression of MEG3 was associated with more favorable 3-year RFS, although the significance of this finding is unclear.

MEG3 is an long non-coding RNA located at the DLK-MEG3 locus on chromosome 14q32.3 and is reported to be a tumor suppressor gene, exerting its effect in part through interaction with tumor suppressor and master regulator p53(26, 27). MEG3 has been reported to be downregulated in multiple solid tumor types(28), which is consistent with what we observed in our 19 HPV-negative HNSCC tumor-adjacent normal pairs. However, our observed association of low MEG3 expression with better 3-year RFS is contrary to what has been reported for other solid tumor types(29) and therefore should be interpreted with caution. In particular, Jia and colleagues found that low expression of MEG3 correlated with poorer outcomes in squamous cell carcinoma of the anterior tongue, and overexpression of MEG3 inhibited cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in SCC-15 and Cal 27 tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell lines(30).

While the other differentially expressed lncRNA transcripts in our study were not associated with OS or RFS in the TCGA head and neck tumors, they have been identified as potential markers for poor prognosis in other cancer types. SPRY4-IT1, which is located on the SPRY4 gene, has been implicated in cell growth invasion and increased apoptosis(31), and elevated expression of SRPY4-IT1 has been associated with poorer outcomes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, which, like HPV-negative HNSCC, is also strongly associated with tobacco and alcohol(32). Overexpression of HEIH has been reported in hepatocellular carcinoma, where it is an independent predictor for recurrence and survival and interacts with the lysine methyltransferase and Polycomb Repressor Complex 2 member Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2)(33). Upregulation of both LUCAT1 and LINC00152 have been associated with poorer outcomes for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)(34, 35), and HAND2-AS1 has been reported to be upregulated in stage IVS neuroblastoma(36) but downregulated in metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma(37), with the latter being more in-line with our narrative of lower expression of HAND2-AS1 in HPV-negative HNSCC.

Strengths of our study include the comprehensive assessment of 84 cancer-associated lncRNA and our ability to access raw RNA-seq data from TCGA. This allowed the alignment of our data with annotated lncRNA sequences to validate our findings in an independent dataset and assess the impact of significantly differential lncRNA on overall and relapse-free survival, and to infer HPV-status by aligning to HPV16 E6/E7 viral mRNA transcripts. Our study also has several limitations, including the modest sample size of our initial discovery set, which may adversely impacted our power to detect smaller effect sizes, increasing the risk of false-negative results. However, our use of a stringent FDR-control and validation in an independent set of tumors using TCGA data yields high confidence in our significant results. Furthermore, since no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons in the survival analyses, we cannot rule out the spurious nature of the observed association between MEG3 and RFS. Additionally, use of archival FFPE tissue for our discovery set likely attenuated the lncRNA expression levels, which could reduce our sensitivity for detection of signal or more subtle differences in expression. Our use of the RNeasy FFPE kit, which is specifically engineered to maximize the integrity and downstream results for RNA extracted from FFPE(38), helps mitigate this issue; it is also notable that 5 of the 7 differentially expressed lncRNA identified with the array were replicated using RNA-seq data from fresh tissue, supporting the validity of our findings.

CONCLUSION

Expression of lncRNA is dysregulated in HPV-negative HNSCC. Specifically, we have identified and validated 5 differentially expressed lncRNA: SPRY4-IT1, HEIH, LUCAT1, LINC00152, and HAND2-AS1. Additional studies are needed to confirm the potential prognostic value of MEG3 expression in HNSCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K22CA172358 to S.M.L) and National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences through the UC Center for Environmental Genetics (2P30ES006096).

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Muir CS. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Comparability and quality of data. IARC Sci Publ. 1992;(120):45–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockstein B, Haraf DJ, Rademaker AW, et al. Patterns of failure, prognostic factors and survival in locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy: a 9-year, 337-patient, multi-institutional experience. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(8):1179–86. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489(7414):101–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauli A, Rinn JL, Schier AF. Non-coding RNAs as regulators of embryogenesis. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011;12(2):136–49. doi: 10.1038/nrg2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra Gupta S, Nandan Tripathi Y. Potential of long non-coding RNAs in cancer patients: From biomarkers to therapeutic targets. Int J Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ijc.30546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cech TR, Steitz JA. The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell. 2014;157(1):77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang G, Lu X, Yuan L. LncRNA: A link between RNA and cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serviss JT, Johnsson P, Grander D. An emerging role for long non-coding RNAs in cancer metastasis. Frontiers in genetics. 2014;5:234. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu MT, Hu JW, Yin R, Xu L. Long noncoding RNA: an emerging paradigm of cancer research. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2013;34(2):613–20. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Eissmann M, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer research. 2013;73(3):1180–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt LH, Spieker T, Koschmieder S, et al. The long noncoding MALAT-1 RNA indicates a poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer and induces migration and tumor growth. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2011;6(12):1984–92. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182307eac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XH, Liu ZL, Sun M, Liu J, Wang ZX, De W. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR indicates a poor prognosis and promotes metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC cancer. 2013;13:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa T, Endo H, Yokoyama M, et al. Large noncoding RNA HOTAIR enhances aggressive biological behavior and is associated with short disease-free survival in human non-small cell lung cancer. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;436(2):319–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao W, An Y, Liang Y, Xie XW. Role of HOTAIR long noncoding RNA in metastatic progression of lung cancer. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2014;18(13):1930–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Zhang P, Wang L, Piao HL, Ma L. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in carcinogenesis and metastasis. Acta biochimica et biophysica Sinica. 2014;46(1):1–5. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Diederichs S. MALAT1 – a paradigm for long noncoding RNA function in cancer. Journal of molecular medicine. 2013;91(7):791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10(3):1–10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossman RL, Heath AP, Ferretti V, et al. Toward a Shared Vision for Cancer Genomic Data. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(12):1109–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colaprico A, Silva TC, Olsen C, et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(8):e71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HT. Cumulative incidence in competing risks data and competing risks regression analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2 Pt 1):559–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, Robson M, Kutler D, Auerbach AD. A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(7):1229–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nohata N, Abba MC, Gutkind JS. Unraveling the oral cancer lncRNAome: Identification of novel lncRNAs associated with malignant progression and HPV infection. Oral Oncol. 2016;59:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou AE, Zheng H, Saad MA, et al. The non-coding landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(32):51211–51222. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang W, Dong K, Li K, Dong R, Zheng S. MEG3, HCN3 and linc01105 influence the proliferation and apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells via the HIF-1alpha and p53 pathways. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36268. doi: 10.1038/srep36268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Zhong Y, Wang Y, et al. Activation of p53 by MEG3 non-coding RNA. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(34):24731–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. MEG3 noncoding RNA: a tumor suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;48(3):R45–53. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui X, Jing X, Long C, Tian J, Zhu J. Long noncoding RNA MEG3, a potential novel biomarker to predict the clinical outcome of cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia LF, Wei SB, Gan YH, et al. Expression, regulation and roles of miR-26a and MEG3 in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(10):2282–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou Y, Jiang Z, Yu X, et al. Upregulation of long noncoding RNA SPRY4-IT1 modulates proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and network formation in trophoblast cells HTR-8SV/neo. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang CY, Li RK, Qi Y, et al. Upregulation of long noncoding RNA SPRY4-IT1 promotes metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2016;32(5):391–401. doi: 10.1007/s10565-016-9341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang F, Zhang L, Huo XS, et al. Long noncoding RNA high expression in hepatocellular carcinoma facilitates tumor growth through enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in humans. Hepatology. 2011;54(5):1679–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renhua G, Yue S, Shidai J, Jing F, Xiyi L. 165P: Long noncoding RNA LUCAT1 is associated with poor prognosis in human non-small cell lung cancer and affects cell proliferation via regulating p21 and p57 expression. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016;11(4 Suppl):S129. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen QN, Chen X, Chen ZY, et al. Long intergenic non-coding RNA 00152 promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation via interacting with EZH2 and repressing IL24 expression. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0581-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voth H, Oberthuer A, Simon T, Kahlert Y, Berthold F, Fischer M. Identification of DEIN, a novel gene with high expression levels in stage IVS neuroblastoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(12):1276–84. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Chen L, Gu J, et al. Recurrently deregulated lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14421. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belder N, Coskun O, Doganay Erdogan B, et al. From RNA isolation to microarray analysis: Comparison of methods in FFPE tissues. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212(8):678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.