Abstract

Background

Self-testing may increase HIV testing and decrease the time people with HIV are unaware of their status, but there is concern that absence of counseling may result in increased HIV risk.

Setting

Seattle, Washington.

Methods

We randomly assigned 230 high-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) to have access to oral fluid HIV self-tests at no cost versus testing as usual for 15 months. The primary outcome was self-reported number of HIV tests during follow-up. To evaluate self-testing’s impact on sexual behavior, we compared the following between arms: non-HIV-concordant condomless anal intercourse (CAI) and number of male CAI partners in the last 3 months (measured at 9 and 15 months) and diagnosis with a bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI: early syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydial infection) at the final study visit (15 months). A post hoc analysis compared the number of STI tests reported during follow-up.

Results

Men randomized to self-testing reported significantly more HIV tests during follow-up (mean=5.3, 95%CI=4.7-6.0) than those randomized to testing as usual (3.6, 3.2-4.0; p<.0001), representing an average increase of 1.7 tests per participant over 15 months. Men randomized to self-testing reported using an average of 3.9 self-tests. Self-testing was non-inferior with respect to all markers of HIV risk. Men in the self-testing arm reported significantly fewer STI tests during follow-up (mean=2.3, 95%CI=1.9-2.7) than men in the control arm (3.2, 2.8-3.6; p=0.0038).

Conclusions

Access to free HIV self-testing increased testing frequency among high-risk MSM and did not impact sexual behavior or STI acquisition.

Keywords: Men who have sex with men, HIV self-testing, sexual behavior, HIV screening, sexually transmitted infections

INTRODUCTION

HIV testing is the entry point into the HIV prevention and care continuum and is critical for reducing ongoing transmission and morbidity. However, traditional testing approaches are not reaching all persons with HIV. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends at least annual testing for MSM and many local health departments recommend more frequent testing for high-risk MSM to decrease time spent undiagnosed1. However, many MSM continue to test infrequently, and estimates suggest 14% of U.S. MSM living with HIV remain unaware of their infection and potential for onward transmission2.

HIV self-testing, which allows testers to use rapid tests on self-collected specimens to learn their status at the time and location of their choosing, has long been proposed as a method to increase testing frequency and reach persons who would not otherwise test3–6. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first HIV self-test, the OraQuick® In-Home HIV Test, in 2012. However, concerns exist regarding the safety, accuracy, and public health impacts of these tests5–10, and few controlled studies have been conducted to clarify the benefits and risks of HIV self-testing, particularly among MSM.11

Before approval of the first self-test, evidence from observational studies and cross-sectional surveys suggested that self-testing would be acceptable and feasible for MSM and would increase testing for individual MSM and within partnerships7,12–24. However, the effect of self-testing on HIV testing frequency and the potential for the absence of risk-reduction counseling to lead to increased HIV risk had not been examined. To that end, we randomized 230 high-risk MSM to have access to HIV self-testing at no cost or to testing as usual to determine whether the availability of self-testing increases testing frequency without negatively impacting HIV risk behaviors.

METHODS

Design Overview

We conducted an open-label randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing using OraQuick ADVANCE® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraQuick; OraSure Technologies, Inc.; Bethlehem, PA) versus standard of care for 15 months among MSM at high risk for HIV acquisition in Seattle, Washington, from September 2010 to December 2014. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Washington (UW) Human Subjects Division. The protocol is available as Supplemental Digital Content 1. An Investigational Device Exemption was received from the FDA for off-label use of OraQuick (BB-IDE 14354). Data were analyzed using Stata version 11 (College Station, TX).

Setting and Participants

In the Seattle area, HIV testing is available to MSM at multiple sites in the community at no charge or on a sliding scale, including the Public Health – Seattle & King County (PHSKC) STD Clinic and community-based organizations, as well as through private providers. PHSKC recommends quarterly HIV testing to MSM at high risk for HIV acquisition, defined as reporting at least one of the following in the prior year: condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with HIV-positive/unknown partners, diagnosis with bacterial STI, methamphetamine or inhaled nitrite use, or ≥10 male sex partners; and annual testing to lower risk MSM25,26.

The study enrolled people assigned male sex at birth and trans men who met the following eligibility criteria: English-speaking, age ≥18 years, reported sex with men in the year before enrollment, had a documented HIV-negative test ≤30 days before enrollment, at high risk per PHSKC, able to provide a stable mailing address, planning to live in the Seattle area for the duration of follow-up, and not participating in other studies with protocol-specified HIV testing at regular intervals. Only high-risk MSM were enrolled so that study recommendations for quarterly testing were uniform among all participants and consistent with PHSKC guidelines.

Participants were recruited from the PHSKC STD Clinic and other Seattle sites serving MSM through advertisements and clinician referral; waiting room recruitment in the STD Clinic; advertisements on Facebook, Google Ads, and local MSM websites; and local LGBTQ listservs. Potential participants without documentation of a negative HIV test in the 30 days before enrollment were tested at an initial in-person study visit. HIV testing included screening via third-generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by pooled nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for acute infection if EIA-negative and Western blot confirmatory testing if EIA-positive27.

Randomization and Intervention

Participants were assigned on a 1:1 basis to the intervention or control arm by variable block randomization; group assignment and block size were concealed from study staff involved in participant interaction until after enrollment. At enrollment, participants randomized to the intervention arm received in-depth training in the performance of OraQuick and a single test to take home. In the absence of an FDA-approved self-test at study initiation, study kits were designed to mirror the test under consideration based on discussions of the FDA’s Blood Products Advisory Committee28,29 and included instructions, pre- and post-test counseling materials, a list of local HIV-related resources, and condoms. Instructions for providers developed by the UW HIV Web Study were adapted for unassisted self-testing30. Additional kits were available on request and could be mailed or picked up at the clinic. To minimize the likelihood of test sharing, participants were limited to 1 kit per month unless needed to replace an invalid, damaged, or misplaced test. After one participant shared his kit with a partner who tested HIV-positive22, the IRB required participants be informed that they would be taken off-study if they shared kits. Study staff maintained a 24-hour telephone contact for procedural questions, technical support, counseling, and scheduling confirmatory testing following reactive self-tests.

Study Procedures

Participants in both arms were required to complete an in-person enrollment visit and an end-of-study visit. At baseline, in the absence of a uniform standard of care for HIV testing, procedures encouraged testing per PHSKC guidelines: all participants were educated regarding acute infection and sites where NAAT was available; advised to test quarterly at a location of their choosing; given a card with recommended testing dates; and offered testing reminders via email, phone, or letter at a frequency of their choosing. Self-administered computer-based questionnaires completed at enrollment and end-of-study visits addressed sociodemographic characteristics, HIV testing, sexual behaviors, substance use, and intentions to use self-tests. To improve retention, all participants were contacted quarterly via email to complete an online survey to update their contact information. The 9-month contact update included questions regarding sexual behavior to improve power to assess the impact of self-testing on risk. At enrollment and end-of-study, participants were screened for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection. Participants who left the Seattle area and completed end-of-study procedures remotely were not screened for HIV/STIs.

Outcomes and Statistical Analyses

Primary objective: Effects on HIV testing frequency

Participants were asked how many times they tested for HIV while enrolled in the study (excluding tests at study visits) as part of the end-of-study questionnaire. Participants completed event history calendars immediately before the questionnaire to assist with recall31. We compared the mean number of HIV tests reported by participants in each arm using the t-test. With a target effective sample size of 197 participants, the study had 84% power to detect a mean difference of 0.58 tests between the two arms. Secondary analyses used Pearson’s χ2 tests to compare (1) the proportion of participants in each arm reporting compliance with PHSKC recommendations to test ≥4 times during follow-up and (2) the proportion of participants in each arm reporting ≥1 test. We estimated replacement of clinic testing with self-tests by subtracting the number of clinic HIV tests reported by men in the self-testing arm (calculated as the total number of tests minus the number of self-tests) from the number of HIV tests reported by men in the control arm. We also conducted an unplanned comparison of the mean number of STI tests reported by participants in both arms using the t-test.

Secondary objective: Effects on sexual behavior and STI diagnosis

To address concerns that the absence of face-to-face risk-reduction counseling in self-testing would result in increased HIV risk, we designed our secondary objective to determine whether self-testing is non-inferior to standard testing with respect to three measures of risk. Outcome definitions, assessment, pre-specified non-inferiority bounds, and statistical methods are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ascertainment and statistical methods for determining non-inferiority of HIV self-testing with respect to sexual behavior and STI acquisition

| Outcome | Definition | Timing of measurement | Statistical method | Non-inferiority definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-concordant condomless anal intercourse (CAI) | Self-reported CAI with HIV-positive or –unknown status partner in last 3 months | 9-month contact update and end-of-study (15-month) surveys | GEE logistic regression, adjusted for repeat measures* | Non-inferior if upper bound of 95%CI of odds ratio (self-testing ÷ standard) is <2 |

| Number of male CAI partners | Self-reported number of male CAI partners in last 3 months | 9-month contact update and end-of-study (15-month) surveys | GEE Poisson regression, adjusted for repeat measures* | Non-inferior if upper bound of 95%CI of fold-difference in number of partners (self-testing ÷ standard) is <2 |

| STI prevalence | Diagnosis with early syphilis or rectal, pharyngeal, or urethral gonorrhea or chlamydial infection | Screening at end-of-study visit | Risk difference[54] | Non-inferior if upper bound of 95%CI for risk difference (self-testing - standard) is <10% |

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) using exchangeable working correlations with either robust standard errors (logistic regression) or robust variance (Poisson regression).

Syphilis was detected using rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and confirmed using the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) assay. Rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal gonorrhea and chlamydial infection were detected using the Aptima Combo 2 (Gen-Probe Inc., San Diego, CA).

Validating Self-Reported Tests

We attempted to validate the total number of HIV tests and self-tests reported by participants in the end-of-study survey directly and indirectly. For clinic tests, we assessed where participants tested during follow-up and requested consent to obtain medical records for confidential tests. The number of confirmed clinic tests was defined as the number of separate clinical visits during follow-up at which an HIV test result was recorded. For self-tests, the number of confirmed tests was defined as the number of self-tests distributed to each participant minus the number participants reported never receiving, having missing or broken parts, sharing with non-participants, and remaining unused at the end of follow-up. Because participants had to actively request additional tests, we assumed that distributed tests that did not meet these criteria were used by participants. We compared the number of reported versus confirmed tests, overall and stratified by testing site and study arm, using paired t-tests. Comparisons of overall and clinic testing were limited to participants who reported no clinic testing or reported all clinic testing as confidential (i.e. name-based) and for whom records (or a confirmed absence of records) could be obtained for all testing sites. Comparisons of self-tests were limited to participants who reported the number of self-tests they performed and confirmed whether they had used all of their self-tests at the end-of-study visit. Finally, we repeated the primary outcome comparison using confirmed tests only.

Acceptability, Ease of Use, and 24-hour Contact Utilization

The enrollment questionnaire assessed anticipated effects of self-testing on testing frequency and, among the first 117 participants, amount willing to pay for a self-test and anticipated effects of cost on self-test use. Ease of use was assessed in the end-of-study questionnaire. Study staff maintained a log of calls to the 24-hour contact.

HIV Diagnosis and Incidence

Participants completing in-person end-of-study visits received HIV testing and were asked to release medical records for review to identify new infections, confirm reported diagnoses, and estimate dates of HIV infection. Incidence of HIV diagnosis was calculated by dividing the number of diagnoses by the total time from enrollment to first positive test or end-of-study visit and compared across study arms using Cox proportional hazards regression.

RESULTS

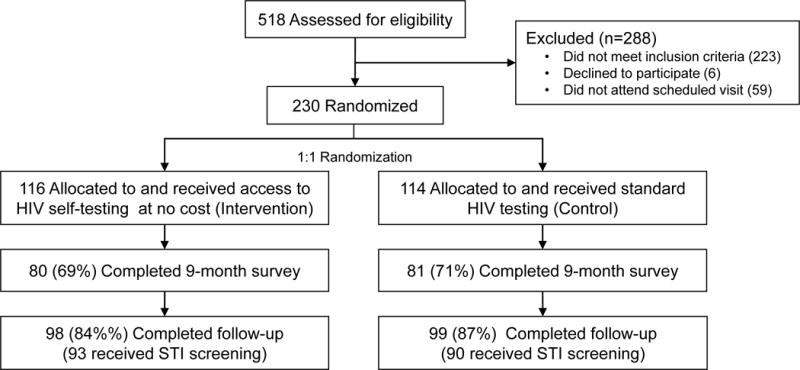

From September 2010 to September 2013, we screened 518 potential participants and enrolled 230 (44%) [Fig. 1]. The majority of participants were white, college-educated, and male-identified and reported testing on a regular schedule [Table 2]. At enrollment, men in the intervention arm were less likely to report having previously used a home HIV test and to test positive for a bacterial STI.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart

Table 2.

Characteristics of 230 men who have sex with men participating in a randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing at baseline, by study arm.

| Characteristic | Self-Testing Arm | Control Arm |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) or Median (IQR) |

N (%) or Median (IQR) |

|

| N = 116 | N = 114 | |

| Age (y) | 35.5 (27 to 45.5) | 37.5 (29 to 47) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 21 (18%) | 13 (12%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 90 (78%) | 79 (73%) |

| Black/African-American | 11 (10%) | 10 (9%) |

| Asian | 5 (4%) | 7 (6%) |

| Multiracial | 7 (6%) | 11 (10%) |

| Other | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 14 (12%) | 14 (13%) |

| Some college, Associate’s degree, or vocational or technical training | 44 (38%) | 32 (29%) |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 57 (50%) | 65 (59%) |

| Living situation | ||

| Alone in a house or apartment | 40 (35%) | 47 (42%) |

| With a sex partner, lover, or spouse | 16 (14%) | 18 (16%) |

| With friends or roommates | 46 (40%) | 31 (27%) |

| With parents, guardians, or other relatives | 4 (3%) | 12 (11%) |

| In school or university dormitories | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| No regular place to stay, couch surfing, homeless, shelter | 8 (7%) | 5 (4%) |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 114 (98%) | 111 (98%) |

| Trans women | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Genderqueer or neutral | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Tested for HIV, last year | 104 (90%) | 108 (95%) |

| Number of HIV tests, last year | 2 (1 to 3) | 2.5 (1 to 4) |

| Currently tests on a regular basis | 66 (57%) | 73 (65%) |

| Ever used a home HIV test | 2 (2%) | 10 (9%) |

| Gender of sex partners, last 3 months | ||

| Men | 107 (92%) | 107 (95%) |

| Women | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Both | 8 (7%) | 6 (5%) |

| Number of male oral or anal sex partners, last 3 months | 5 (3 to 10) | 5.5 (3 to 10) |

| Number of male condomless anal intercourse (CAI) partners, last 3 months | 1 (0.5 to 2) | 1 (1 to 3) |

| Any CAI with an HIV-positive partner or partner of unknown HIV status, last 3 months | 37 (35%) | 34 (31%) |

| Methamphetamine use, last 3 months | 12 (10%) | 10 (9%) |

| Inhaled nitrite use, last 3 months | 39 (34%) | 35 (31%) |

| Diagnosis of any bacterial STI at enrollment visit | 9 (8%) | 19 (17%) |

| Gonorrhea | 3 (3%) | 7 (6%) |

| Chlamydial infection | 5 (4%) | 11 (10%) |

| Syphilis | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) |

| Accepted HIV testing reminders | 97 (84%) | 89 (78%) |

Of enrolled participants, 197 (86%) completed study follow-up with no differences in retention between arms [98 (84%) and 99 (87%) in the self-testing and control arms, respectively; p=0.6]. Of these 197, 194 participants completed ~15 months of follow-up, and 3 tested positive during follow-up, who completed an end-of-study visit at 3, 10, and 12 months. Median duration of follow-up for participants who completed the study was 15 months and did not differ by arm (p=0.8). Of 33 who did not complete the study, 1 withdrew early and did not complete an end-of-study visit, and 32 were lost to follow-up. Being older, greater educational attainment, and reporting testing regularly before enrollment were associated with study completion (p<0.05 for all).

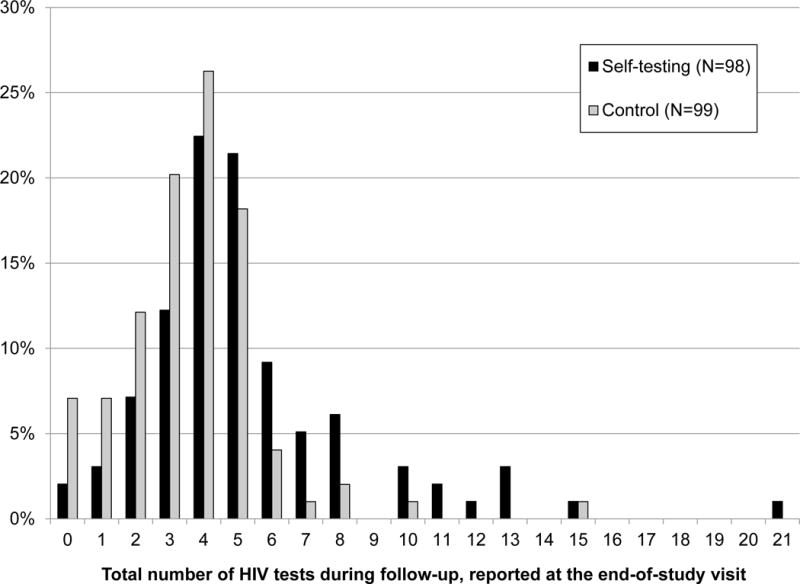

Effect of Self-Testing on HIV Testing Frequency

Among the 197 men who completed the study, men randomized to self-testing reported significantly more HIV tests during follow-up (mean=5.3, 95%CI=4.7-6.0) than those in the control arm (3.6, 3.2-4.0; p<.0001), representing an average increase of 1.7 tests per participant over 15 months (95%CI=0.9-2.5; Fig. 2). Almost all men reported testing at least once (98% self-testing arm vs. 93% control, p=0.17), but men in the self-testing arm were significantly more likely to report at least quarterly testing as recommended (76% vs. 54%, respectively; p=0.001). Among men randomized to self-testing, 77% reported testing more often during follow-up than they would have without access to self-testing, 22% as often, and 1% less often.

Figure 2.

Distribution of self-reported number of HIV tests during 15 months of follow-up among men who have sex with men participating in a randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing, by study arm

Of the 98 men randomized to self-testing who completed follow-up, 40 (41%) reported only using self-tests, 48 (49%) reported self-testing and clinic-based testing, and 10 (10%) reported only clinic-based testing. The mean number of self-tests reported was 3.9 (range=0-16). Men randomized to self-testing tested at clinics an average of 1.4 times during follow-up (vs. 3.6 among controls; p<0.0001), suggesting that they replaced an average of 2.2 clinic-based tests with 3.9 self-tests. Men in the self-testing arm reported significantly fewer STI tests during follow-up (mean=2.3, 95%CI=1.9-2.7) than men in the control arm (3.2, 2.8-3.6; p=0.0038).

Effects of Self-Testing on Measures of HIV Risk

Self-testing was non-inferior to clinic-based testing with respect to all three markers of HIV risk (Table 3). At the 9-month and end-of-study surveys, men in the self-testing arm reported 8% fewer male CAI partners in the prior 3 months than men in the control arm (incidence rate ratio=0.92, 95%CI=0.64-1.33). At the 9-month and end-of-study surveys, men randomized to self-testing were 1.07-fold more likely to report non-concordant CAI in the prior 3 months than men in the control group (odds ratio=1.07, 95%CI=0.61-1.90). Of 183 who received STI screening at the end-of-study visit, 5.4% (5/93) of MSM randomized to self-testing were diagnosed with a bacterial STI compared with 12.2% (11/90) of control participants [risk difference=−6.8%; 95%CI=−16 to +1.6%].

Table 3.

Effects of access to HIV self-testing on HIV risk during follow-up

| Marker for risk of HIV acquisition | At 9 months of follow-up | At end-of-study | Point estimate of difference1 (self-testing vs. control) | 95% CI | Non-inferiority bound | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-testing | Control | Self-testing | Control | ||||

| Non-concordant CAI, last 3 months (%) | 21% | 22% | 29% | 24% | Odds ratio = 1.07 | 0.61 to 1.90 | 2.00 |

| No. male CAI partners, last 3 months (mean) | 1.38 | 2.05 | 2.34 | 2.14 | Incidence rate ratio = 0.92 | 0.64 to 1.33 | 2.00 |

| Bacterial STI diagnosis at end of study (%) | - | - | 5.4% | 12.2% | Risk difference = −6.8% | −16% to 1.6% | +10% |

STI = sexually transmitted infection (early syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydial infection). CAI = condomless anal intercourse. CI = confidence interval.

Point estimates for non-concordant CAI and number of male CAI partners include data from measurements at month 9 and end of study (month 15). The estimate for bacterial STI diagnosis includes data from end of study only.

Validation of HIV Testing

There were 130 men (66% of total) for whom all HIV tests had the potential to be verified through medical record review or self-test distribution. In this group, the 69 men randomized to self-testing had significantly more confirmed tests during follow-up (mean=4.7, 95%CI=4.0-5.4) than the 61 in the control arm (2.5, 2.1-2.9; p<.0001), representing 2.2 additional tests per participant over 15 months (95%CI=1.4-3.1). Overall, men reported a greater number of tests than could be confirmed (mean reported=4.5 vs. confirmed=3.6; p<0.0001). This difference was greater among men randomized to standard testing (4.0 vs. 2.5; p<0.0001) than self-testing (4.9 vs. 4.7; p=0.32). Men in the self-testing arm significantly over-reported self-test use (mean reported=4.0 vs. distributed=3.4; p=0.0018) but were fairly accurate when reporting clinic-based tests (mean reported=1.8 vs. confirmed=1.9; p=0.64).

Acceptability, Ease of Use, and 24-Hour Contact Utilization

At enrollment, 99 (85%) of 117 men expected that they would test for HIV more often if they had access to self-tests. Only 15% reported that they would pay $40 or more for a self-test, 27% would pay $20-$40, 33% would pay $10-$20, 13% would pay less than $10, and 12% would only use a self-test if it were free. How often men thought they would use a self-test to test themselves for HIV infection depended on the cost; 87% expected to test 4 or more times per year if the test cost $5 compared to 23% if it cost $50 (McNemar’s test: p<0.001).

Almost all 88 men who reported using a self-test during follow-up reported the test was very easy to use (94%) and being very sure they used it correctly (93%). However, the package insert indicates the test requires ≥20 minutes to develop, and 9% of men who self-tested reported that, the last time they self-tested, they spent <20 minutes from opening the kit to test interpretation. The 24-hour contact was only used for requesting new kits, not for counseling or help using the test.

New HIV diagnoses

Of 178 participants who received HIV testing at their end-of-study visit, 6 (3.4%) were HIV-positive, four in the self-testing arm and two in the standard testing arm. Incidence of HIV diagnosis was 2.75 per 100 person-years (95%CI=1.23-6.11; compared to an estimated HIV incidence of 0.5 per 100 person-years among MSM overall32) and did not differ by arm (p=0.4). Of the four in the self-testing arm, one sought care with his primary care provider for symptoms of primary infection following the recent HIV diagnosis of his main partner. He reported self-testing positive in the week after this provider visit and before receiving laboratory test results including a viral load >1 million. Of the other three, one reported his last negative test as a self-test two months prior to diagnosis at the end-of-study visit; one reported a negative self-test approximately one month before receiving his diagnosis at a routine physical exam, during which his provider noted signs of primary infection and his rapid HIV test was reactive; and one reported a negative self-test 5 days before a previously scheduled clinic test which indicated primary infection. All were linked to HIV care.

DISCUSSION

This study, among the first of its kind to evaluate the implementation of self-testing, demonstrated that access to HIV self-testing at no cost increased testing frequency among high-risk MSM in Seattle and had no effect on STI acquisition or sexual risk behaviors. However, the HIV testing histories of the few men who became infected during the study suggested that the availability of self-tests did not result in earlier HIV diagnosis, and participants enrolled in the self-testing arm had fewer tests for bacterial STIs in an environment with increasing rates of syphilis and gonorrhea33.

Our results are similar to a recently published trial among urban Australian MSM that found that access to self-testing led to a 2-fold increase in the number of HIV tests reported in the prior year (an absolute increase in 2.1 tests) and had no effect on CAI with casual partners34. It is encouraging that, in both settings and among MSM with varying histories of HIV testing, both studies observed large increases in testing frequency despite high levels of testing in the control groups (approximately every 4-5 vs. 6 months in the Seattle and Australian trials, respectively), and that neither study observed increases in indicators of HIV risk in the absence of counseling. However, in a setting where most men test frequently35, we were unable to confirm whether self-testing had a large effect on HIV testing frequency among non-recent testers. The potential for self-testing to reach non- or infrequent testers may provide unique population- and individual-level benefits, an issue we are exploring using mathematical modeling. In addition, in contrast to the Australian trial where self-testing appears to have supplemented clinic-based testing and did not affect STI testing, we found evidence of significant replacement of clinic-based tests with self-tests and a decrease in reported STI testing frequency among MSM in the self-testing arm. Our previous modeling work suggested that replacing clinic-based testing with self-testing in settings where clinics provide antigen-antibody tests or pooled NAAT has the potential to increase HIV transmission because the long window period of the FDA-approved self-test makes it unable to diagnose persons during early infection when they are most infectious36. Research is needed to understand the differences in these results and how self-testing affects clinic-based HIV/STI testing in different settings as well as to develop and evaluate self-tests able to detect early HIV infection. Fingerstick HIV self-tests, which may have greater sensitivity and shorter window periods37, have been introduced in some settings and studies38–41; however, the effects of access to oral fluid self-tests on HIV testing may not translate directly to fingerstick self-tests, which may differ in acceptability and usability38,42.

The study has several limitations. First, it was conducted among high-risk MSM in Seattle who agreed to participate in a self-testing trial and may not be generalizable to other settings or populations. Second, testing and sexual behavior outcomes relied on self-report and were therefore subject to recall error and selection bias. This is of particular concern because we were unable to blind participants to study arm. Comparing only confirmed tests yielded an even stronger association between self-testing and increased testing than the primary analysis, although this analysis was also sensitive to the limitations of directly measuring self-testing. In addition, the trial was powered for the primary outcome of HIV testing frequency and had limited power for non-inferiority and HIV diagnosis-related outcomes, and STI acquisition and sexual risk behaviors do not always correlate directly with HIV risk43,44. The OraQuick In-Home HIV Test became available for purchase during the study and may have affected participants’ testing behaviors, particularly with respect to self-testing. However, the intervention effect remained consistent before and after its introduction (Supplemental Digital Content 2). Adapting the professional OraQuick for self-testing instead of using FDA-approved self-tests may have affected self-test acceptability and performance. The trial was also conducted prior to widespread availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Seattle, and our results might differ in a setting with frequent PrEP use, where oral fluid testing is actively discouraged due to poor sensitivity in early infection45,46 and delayed seroconversion in oral fluids among PrEP users47. Finally, randomization did not result in complete balance of measured potential confounders between arms. However, controlling for unbalanced factors did not affect estimates of the effects of self-testing on testing or risk (Supplemental Digital Content 3 and 4).

Self-testing has great potential to increase awareness of HIV status among MSM, particularly if it can reach those who have never tested or test infrequently. Among men who already test for HIV, self-testing can be used to supplement clinic-based testing and encourage routine or more frequent testing. How best to accomplish these goals is as yet unknown, but a number of strategies are emerging as feasible and acceptable to MSM48, including via geosocial networking apps49, bathhouses50, self-test vending machines51, vouchers for free self-tests52, mass distribution online or at LGBTQ-focused events53,54, and distribution by sex partners20,38. It will be important to develop strategies for matching the correct self-test distribution models to the appropriate populations and settings and to the capacity of the implementing agency.

In summary, while our results demonstrate the potential benefit of HIV self-tests, much work remains to be done. Research is needed to understand how to prioritize supplementation and reach new testers, to educate men about the limitations of the current self-test, and to invest in the development and evaluation of self-tests able to detect early infection. The potential for HIV self-testing to decrease STI testing despite a growing STI epidemic among MSM also points to the need to develop, evaluate, and integrate STI tests into HIV self-testing programs and products. To maximize the individual- and population-level benefits of self-testing, research is necessary to evaluate and ensure timely linkage to HIV care and prevention, including PrEP, following self-testing and ultimately to identify the most cost-effective methods of implementing self-testing in high-risk populations.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1.doc

Supplemental Digital Content 2.doc

Supplemental Digital Content 3.doc

Supplemental Digital Content 4.doc

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study participants and study staff. We would also like to thank the Public Health – Seattle & King County HIV/STD Program and Seattle LGBTQ community-based organizations and healthcare providers for their support and the Northwest AIDS Education & Training Center for their assistance in creating instructions for the HIV self-test.

Source of Funding: MRG receives test kits for research from Hologic, Inc. JDS received test kits for research from Alere.

This trial was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number R01 MH086360). Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number R21 HD080523) and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757).

Footnotes

Note: This work was presented in part at the 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention, Vancouver, BC.

Conflicts of Interest: The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

The randomized controlled trial described in this manuscript is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01161446).

References

- 1.DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Irwin K, et al. Recommendations for HIV Screening of Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(31):830–832. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6631a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives using HIV surveillance data–United States and 6 dependent areas, 2014. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2016. Available http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

- 3.Merson MH, Feldman EA, Bayer R, Stryker J. Rapid self testing for HIV infection. Lancet. 1997;349(9048):352–353. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spielberg F, Levine RO, Weaver M. Self-testing for HIV: a new option for HIV prevention? Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(10):640–646. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell S, Klein R. Home testing to detect human immunodeficiency virus: boon or bane? J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(10):3473–3476. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01511-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers JE, El-Sadr WM, Zerbe A, Branson BM. Rapid HIV self-testing: long in coming but opportunities beckon. AIDS. 2013;27(11):1687–1695. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd7a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood BR, Ballenger C, Stekler JD. Arguments for and against HIV self-testing. Hiv/Aids. 2014;6:117–126. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S49083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD. Rapid HIV testing at home: does it solve a problem or create one? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):459–462. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paltiel AD, Walensky RP. Home HIV testing: good news but not a game changer. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(10):744–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagnon M, French M, Hebert Y. The HIV self-testing debate: where do we stand? BMC international health and human rights. 2018;18(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12914-018-0146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson CC, Kennedy C, Fonner V, et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Society. 2017;20(1):21594. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skolnik HS, Phillips KA, Binson D, Dilley JW. Deciding where and how to be tested for HIV: what matters most? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27(3):292–300. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma A, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM. Willingness to Take a Free Home HIV Test and Associated Factors among Internet-Using Men Who Have Sex with Men. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011;10(6):357–364. doi: 10.1177/1545109711404946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spielberg F, Branson BM, Goldbaum GM, et al. Overcoming barriers to HIV testing: preferences for new strategies among clients of a needle exchange, a sexually transmitted disease clinic, and sex venues for men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(3):318–327. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200303010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greacen T, Friboulet D, Blachier A, et al. Internet-using men who have sex with men would be interested in accessing authorised HIV self-tests available for purchase online. AIDS Care. 2013;25(1):49–54. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greacen T, Friboulet D, Fugon L, Hefez S, Lorente N, Spire B. Access to and use of unauthorised online HIV self-tests by internet-using French-speaking men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(5):368–374. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pant Pai N, Sharma J, Shivkumar S, et al. Supervised and unsupervised self-testing for HIV in high- and low-risk populations: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilardi JE, Walker S, Read T, et al. Gay and Bisexual Men’s Views on Rapid Self-Testing for HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2093–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balan IC, Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, Ibitoye M. The Impact of Rapid HIV Home Test Use with Sexual Partners on Subsequent Sexual Behavior Among Men Who have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):254–62. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0497-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C. Use of a Rapid HIV Home Test Prevents HIV Exposure in a High Risk Sample of Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1753–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, Balan I. Will Gay and Bisexually Active Men at High Risk of Infection Use Over-the-Counter Rapid HIV Tests to Screen Sexual Partners? J Sex Res. 2012;49(4):379–87. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.647117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz DA, Golden MR, Stekler JD. Use of a home-use test to diagnose HIV infection in a sex partner: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):440. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, Baggaley R. Attitudes and Acceptability on HIV Self-testing Among Key Populations: A Literature Review. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(11):1949–1965. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause J, Subklew-Sehume F, Kenyon C, Colebunders R. Acceptability of HIV self-testing: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:735. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menza TW, Hughes JP, Celum CL, Golden MR. Prediction of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(9):547–555. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a9cc41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Health - Seattle & King County HIV/STD Program. Public Health - Seattle & King County HIV testing and STD screening recommendations for men who have sex with men (MSM) Seattle: 2010. Available: http://www.kingcounty.gov/depts/health/communicable-diseases/hiv-std/providers/screening-testing-msm.aspx. Accessed 24 Oct 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(3):444–453. doi: 10.1086/600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blood Products Advisory Committee: 86th Meeting. Gaithersburg, Maryland: 2006. Proposed Studies to Support the Approval of Over-the-Counter (OTC) Home Use HIV Test Kits. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blood Products Advisory Committee: 96th Meeting. Bethesda, Maryland: 2009. Public Health Need and Performance Characteristics for Over-the-Counter Home-Use HIV Test Kits. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung MH, Severynen AO, Hals MP, Harrington RD, Spach DH, Kim HN. Offering an American graduate medical HIV course to health care workers in resource-limited settings via the Internet. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belli RF. The structure of autobiographical memory and the event history calendar: potential improvements in the quality of retrospective reports in surveys. Memory. 1998;6(4):383–406. doi: 10.1080/741942610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Bell TR, Kerani RP, Golden MR. HIV Incidence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men After Diagnosis With Sexually Transmitted Infections. Sex Transm Dis Apr. 2016;43(4):249–254. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Public Health – Seattle & King County HIV/STD Program. 2015 King County Sexually Transmitted Diseases Epidemiology Report. Seattle: 2016. Available: http://www.kingcounty.gov/depts/health/communicable-diseases/hiv-std/patients/epidemiology/~/media/depts/health/communicable-diseases/documents/hivstd/2015-STD-Epidemiology-Report.ashx. Accessed 24 Oct 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jamil MS, Prestage G, Fairley CK, et al. Effect of availability of HIV self-testing on HIV testing frequency in gay and bisexual men at high risk of infection (FORTH): a waiting-list randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(6):e241–50. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Swanson F, Buskin SE, Golden MR, Stekler JD. HIV intertest interval among MSM in King County, Washington. Sex Transm Infect Feb. 2013;89(1):32–37. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz DA, Cassels SL, Stekler JD. Replacing clinic-based tests with home-use tests may increase HIV prevalence among Seattle men who have sex with men: evidence from a mathematical model. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(1):2–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stekler JD, Ure G, O’Neal JD, et al. Performance of Determine Combo and other point-of-care HIV tests among Seattle MSM. J Clin Virol. 2016;76:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lippman SA, Lane T, Rabede O, et al. High Acceptability and Increased HIV-Testing Frequency After Introduction of HIV Self-Testing and Network Distribution Among South African MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(3):279–287. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prazuck T, Karon S, Gubavu C, et al. A Finger-Stick Whole-Blood HIV Self-Test as an HIV Screening Tool Adapted to the General Public. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0146755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gresenguet G, Longo JD, Tonen-Wolyec S, Mboumba Bouassa RS, Belec L. Acceptability and Usability Evaluation of Finger-Stick Whole Blood HIV Self-Test as An HIV Screening Tool Adapted to The General Public in The Central African Republic. Open AIDS J. 2017;11:101–118. doi: 10.2174/1874613601711010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens DR, Vrana CJ, Dlin RE, Korte JE. A Global Review of HIV Self-testing: Themes and Implications. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(2):497–512. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neal JD, Golden MR, Branson BM, Stekler JD. HIV Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing Versus Rapid Testing: It Is Worth the Wait. Testing Preferences of Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(4):e119–122. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825aab51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, et al. Effect of risk-reduction counseling with rapid HIV testing on risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections: the AWARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1701–1710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khosropour CM, Dombrowski JC, Swanson F, et al. Trends in Serosorting and the Association With HIV/STI Risk Over Time Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):189–197. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stekler JD, O’Neal JD, Lane A, et al. Relative accuracy of serum, whole blood, and oral fluid HIV tests among Seattle men who have sex with men. J Clin Virol. 2013;58(Suppl 1):e119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf. Accessed 24 Oct 2017.

- 47.Curlin ME, Gvetadze R, Leelawiwat W, et al. Analysis of false-negative HIV rapid tests performed on oral fluid in three international clinical research studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(12):1663–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Estem KS, Catania J, Klausner JD. HIV Self-Testing: a Review of Current Implementation and Fidelity. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2016;13(2):107–115. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang E, Marlin RW, Young SD, Medline A, Klausner JD. Using Grindr, a Smartphone Social-Networking Application, to Increase HIV Self-Testing Among Black and Latino Men Who Have Sex With Men in Los Angeles, 2014. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016;28(4):341–350. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods WJ, Lippman SA, Agnew E, Carroll S, Binson D. Bathhouse distribution of HIV self-testing kits reaches diverse, high-risk population. AIDS Care. 2016;28(Suppl 1):111–113. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1146399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young SD, Klausner J, Fynn R, Bolan R. Electronic vending machines for dispensing rapid HIV self-testing kits: a case study. AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):267–269. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marlin RW, Young SD, Bristow CC, et al. Piloting an HIV self-test kit voucher program to raise serostatus awareness of high-risk African Americans, Los Angeles. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katz DA, Bennett AB, Dombrowski JC, Hood JE, Buskin SE, Golden MR. Presented at: 2015 National HIV Prevention Conference. Atlanta, GA: 2015. Monitoring the Population-Level Impact of HIV Self-Testing through HIV Surveillance and Partner Services. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edelstein ZR, Salcuni PM, Tsoi B, Kobrak P, Andaluz A, Katz D, et al. Presented at: CROI 2017. Seattle, WA: 2017. Feasibility and Reach of a HIV Self-Test (HIVST) Giveaway, New York City, 2015-16. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):873–890. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<873::aid-sim779>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1.doc

Supplemental Digital Content 2.doc

Supplemental Digital Content 3.doc

Supplemental Digital Content 4.doc