Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of corneal neovascularization misdiagnosed as total limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD).

Methods

This case report presents a 61-year-old female who has a history of bilateral idiopathic scleritis, keratitis and uveitis for more than 20 years. She was diagnosed with total LSCD in her left eye based on clinical presentation alone and was confirmed as a candidate for limbal transplantation at several major tertiary eye centers in the United States. After referral to our institute, in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) and anterior segment optical coherent tomography (AS-OCT) were performed to clarify the diagnosis.

Results

Slit-lamp examination of the left eye found that there was 360 degree of severe thinning at the limbus and peripheral corneal pannus/neovascularization that spared the central cornea, a smooth epithelium without fluorescein staining at the central cornea, an uneven surface, and pooling of fluorescein at the peripheral cornea accompanied by minimal fluorescein staining of the sectoral peripheral epithelium. IVCM showed that epithelial cells in the central cornea exhibited a corneal phenotype and that the morphology of the epithelium in all limbal regions except the nasal limbus was that of normal limbal epithelium. Epithelial cellular density and thickness were within the range seen in normal subjects. AS-OCT showed severe thinning in the limbus and a normal epithelial layer in the cornea and limbus. Based on the findings of IVCM and AS-OCT, we concluded that the patient had minimal LSCD, and LSCT was not recommended.

Conclusions

Clinical presentation alone is insufficient to correctly diagnose LSCD in complex cases. Additional diagnostic tests, such as IVCM, are necessary to confirm the diagnosis before any surgical intervention.

Keywords: limbal stem cell deficiency, in vivo confocal microscopy, diagnosis, corneal neovascularization, pannus

Introduction

Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) is a disorder caused by the dysfunction and/or the loss of limbal stem cells (LSCs). The diagnosis of LSCD has been made mainly on the basis of medical history and clinical signs including irregular and opacified corneal epithelium, recurrent epithelial defects, late fluorescein staining, and neovascularization of cornea. The clinical presentation might not be specific to LSCD in complex cases. The recent finding that residual limbal epithelial cells could be present in the eyes with clinical presentation of total LSCD1 indicates that it is challenging to assess the severity accurately on the basis of clinical presentation alone. Here we report a case of cornea neovascularization and scleritis that was misdiagnosed as total LSCD at several major tertiary eye centers in the United States.

Case presentation

The 61-year-old woman with a history of bilateral scleritis, keratitis, and uveitis for more than 20 years came to our center from New York City to undergo an allogeneic keratolimbal transplantation. Previous extensive workups for autoimmune diseases were negative. She was treated with short courses of systemic mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, and daclizumab. Because of side effects, the systemic treatments were stopped. She had not received any systemic immunosuppressive therapy for many years. Two years ago, she suffered a globe rupture from a minor self-inflicted injury due to severe scleral thinning in her right eye. Chronic inflammation and exudative retinal detachment occurred after the trauma, she lost most of her vision in the right eye. Her left eye was her functional eye for most of her life. Although the long-term keratitis eventually led to stromal scarring, she maintained visual acuity of counting fingers after cataract surgery, which was performed several years ago. Total LSCD in her left eye was diagnosed by experienced cornea specialists 1 year ago, and she was confirmed as a candidate for limbal stem cell transplantation (LSCT) at three tertiary eye centers and for a Boston type I keratoprosthesis at one center. Impression cytology (IC) and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) had not been performed to confirm the diagnosis of LSCD. She was scheduled to undergo a living-related allogenic conjunctival keratolimbal transplantation per the recommendation of the consulting corneal specialists. Her brother, who is 70% HLA-matched, agreed to serve as the donor. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy after the surgery was also planned. However, the patient wanted a second opinion and was referred to our institute.

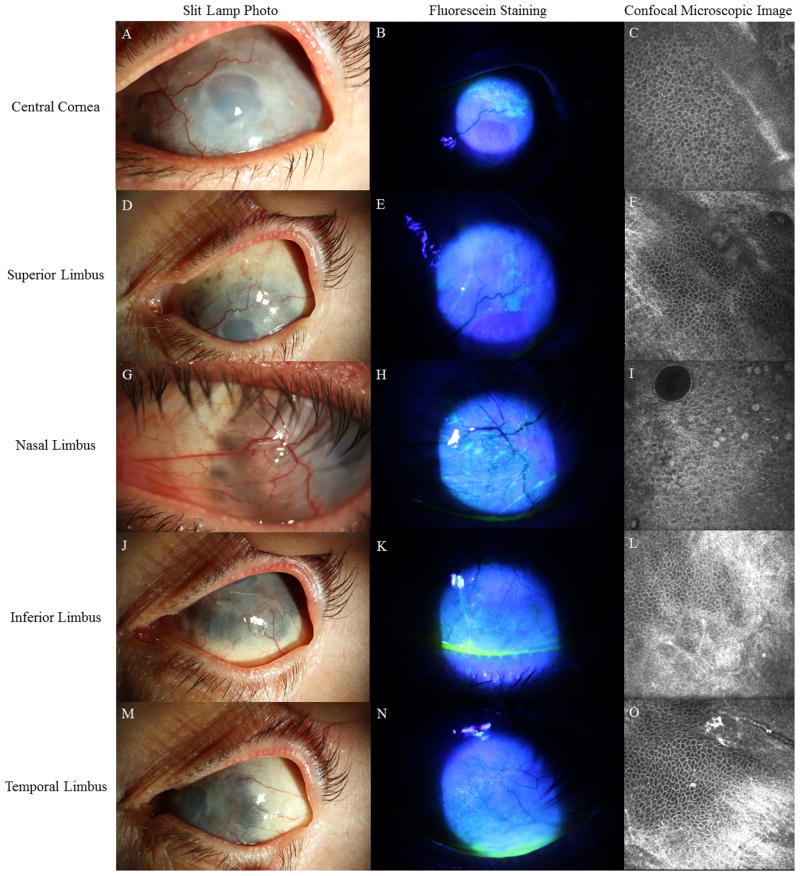

At presentation, her best corrected visual acuity was light perception in the right eye and hand motion in the left eye. On slit-lamp examination, her right eye was pre-phthisis with an edematous and opaque cornea. Her left eye had 360 degree of severe thinning with uveal show at the entire limbus accompanied by peripheral pannus and corneal neovascularization that spared the central 2-mm cornea (Figure 1A, 1D, 1G, 1J, 1M). Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the left eye showed a smooth epithelium without fluorescein staining despite stromal hazy and edema in the central cornea. Mild sectoral fluorescein staining was only present in the extreme periphery (Figure 1B, 1E, 1H, 1K, 1N). The anterior chamber was shallow, and a posterior chamber lens was present. There was no view to the posterior pole in either eye. She was on Durezol eight time a day in both eyes and not on systemic medication for her scleritis and uveitis.

Figure 1.

Slit-lamp photos and confocal microscopy images of the patient’s left eye. Panels A, D, G, J, and M show images taken under white light. Panels B, E, H, K, and N show images with fluorescein staining. In panels C, F, I, L, and O are confocal images. The central cornea is hazy and edematous and lacks neovascularization (A). The surface of the peripheral cornea is covered by pannus and superficial vessels (panels D, G J, M). The severe scleral thinning is seen within the limbal area. Sectoral epithelial staining is present at the nasal and superior limbus (B, E, H, K, N). Confocal images show that the cellular morphology at the central cornea is normal, which are characterized by small cell size, dark cytoplasm, and distinct cell-cell borders in a regular pattern (C). Conjunctivalized epithelium and goblet cells are found only at the nasal limbus (I). The morphology of basal epithelial cells appears to be normal at the superior, inferior, and temporal limbus (F, L, O).

The smooth and transparent epithelial layer on the cornea indicated that the epithelium might be a corneal phenotype. Therefore, IVCM was performed to distinguish the phenotype of epithelium at the central cornea, and superior, nasal, temporal and inferior quadrants of the limbus. The confocal images obtained at central cornea showed that the epithelial morphology was consistent with a corneal phenotype: superficial cells were loosely arranged polygonal flat cells; wing cells had a similar morphology as basal cells but bigger cell size; and basal cells were regularly arranged with dark cytoplasm, bright cell borders and invisible nuclei (Figure 1C). The morphology of basal epithelial cells in the limbal regions were consistent with normal limbal epithelial cells, except those in the nasal quadrant (Figure 1F, 1L, 1O) where conjunctival epithelium and goblet cells were detected (Figure 1I). The palisades of Vogt were not detected in any of the quadrants. The basal epithelial cell densities (BCD) were 8265 cells/mm2 in the central cornea, 7859 cells/mm2 in the superior limbus, 7391 cells/mm2 in the inferior limbus, 8385 cells/mm2 in the temporal limbus, and 5462 cells/mm2 in the nasal limbus. The BCD, except that in the nasal limbus, was within the range reported in normal subjects.2,3 Mild hyper-reflectivity suggested the presence of fibrous tissues at Bowman’s layer (Figure 1C).

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) showed that the corneal epithelium was hypo-reflective and smooth despite the hyper-reflective and irregular interface between the epithelium and Bowman’s layer (Figure 2C). The average thickness of central corneal epithelium was 54 μm, which was also within the normal range.4 AS-OCT detected extreme thinning of the limbus and sclera which was consistent with the finding from clinical exam (Figure 2D). On the basis of the results of IVCM and AS-OCT, our diagnosis was mild sectoral LSCD without central cornea involvement. Therefore, the patient would not benefit from LSCT and the surgery was cancelled. The patient had persistent ocular surface inflammation and we recommended a better control of the inflammation first. Because of the severe thinning down to 260 μm in the peripheral cornea and limbus, as shown by AS-OCT (Figure 2D), there might not be enough host tissue to safely anchor a penetrating keratoplasty or Boston type I keratoprosthesis. A lamellar keratoplasty on the peripheral corneal and limbus followed by penetrating keratoplasty or keratoprosthesis could be an option. Alternatively, a small penetrating keratoplasty might be feasible. The patient returned to New York City for management.

Figure 2.

AS-OCT images of a normal eye, an eye diagnosed with LSCD, and the present patient’s left eye. The corneal epithelium is hyporeflective in the normal eye, with a regular interface between the epithelium and Bowman’s membrane (A). The epithelium thickness at the central cornea is 55 μm in this eye. In contrast, the corneal epithelium is hyper-reflective in the eye diagnosed with LSCD (B), with a decreased epithelial thickness of 37 μm. In the present case described here, the corneal epithelium of the left eye is hypo-reflective, which is similar to that of the normal eye shown in panel A. However, the interface between epithelium and underlying stroma is irregular, with hyper-reflective tissue at Bowman’s membrane, anterior stroma, and deep stroma(C). The epithelial thickness was measured manually at five locations in the central cornea with an interval of 0.5 mm because of subbasal epithelial scarring and the irregular interface between epithelium and stroma. The mean thickness is 54 μm, and the range is 38 μm to 64 μm. There was a severe thinning of peripheral cornea and limbus, with the thickness down to 260 μm (D).

Discussion

This case highlights the challenges of correctly diagnosing and staging of LSCD by clinical examination alone. In complex cases such as this one, clinical examination is insufficient for diagnosis. Even in eyes that appear to have total LSCD at the time of clinical presentation, normal limbal epithelial cells and corneal epithelial cells may still be found by IVCM.1

Peripheral pannus and neovascularization are often considered as a typical presentation of LSCD,5 and both are also the most prominent clinical findings in this case. However, pannus and neovascularization are not specific to LSCD and are often present in other ocular diseases without a component of LSCD. In the present case, the severe scleral thinning accompanied by corneal neovascularization were mistaken as signs of total LSCD. LSCT and systemic immunosuppression were not the correct treatment and would have subjected her to the risks of surgery and life-threatening side effects of systemic immunosuppression.

The use of IC or IVCM to confirm the diagnosis of LSCD has been well established.6,7 IC confirms the diagnosis of LSCD by either detecting goblet cells using Periodic acid-Schiff staining or a conjunctival epithelial marker cytokeratin 13 or 7 expression on the corneal surface using immunostaining.8,9 The detection of goblet cells by IC was the first established diagnostic test for LSCD, but the sensitivity is low in eyes with concomitant goblet cell deficiency.10 Use of specific cytokeratin expressed by the corneal and conjunctival epithelium has a higher sensitivity and specificity than the detection of goblet cells.6

IVCM is a noninvasive in vivo imaging modality to diagnose LSCD with a good concordance with IC using conjunctival marker.6 In this case, IVCM alone was sufficient to detect normal corneal epithelium on the cornea surface and normal limbal epithelium in the limbal regions without the need of IC. Detection of conjunctival epithelium and goblet cells in the nasal quadrant was apparent. Because of a good concordance between IVCM and IC, IC might not be clinically necessary in cases that IVCM is able to provide precise distribution of the corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells on the cornea to diagnose.

In summary, a correct diagnosis and an accurate assessment of the quantity of residual LSCs serve as the premise of an appropriate treatment recommendation. Clinical presentation alone is not sufficient for correctly diagnosing LSCD. Additional test, such as IVCM or IC, is necessary to avoid unnecessary surgeries and possible harm to patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This work was funded in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness and SXD received research funding from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors has financial interests related to the content of the manuscripts.

References

- 1.Chan E, Le Q, Codriansky A, et al. Existence of normal limbal epithelium in eyes with clinical signs of total limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea. 2016;35:1483–1487. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miri A, Al-Aqaba M, Otri AM, et al. In vivo confocal microscopic features of normal limbus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:530–536. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan EH, Chen L, Rao JY, et al. Limbal basal cell density decreases in limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y, Hong J, Deng SX, et al. Age-related changes in human corneal epithelial thickness measured with anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:5032–5038. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Q, Xu J, Deng SX. The diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. Ocul Surf. 2018;16:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nubile M, Lanzini M, Miri A, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy in diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng SX, Sejpal KD, Tang Q, et al. Characterization of limbal stem cell deficiency by in vivo laser scanning confocal microscopy: a microstructural approach. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:440–445. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez-Miranda A, Nakatsu M, Zarei-Ghanavati S, et al. Keratin 13 is a more specific marker of conjunctival epithelium than keratin 19. Mol Vis. 2011;17:1652–1661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poli M, Burillon C, Auxenfans C, et al. Immunocytochemical diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency: Comparative analysis of current corneal and conjunctival biomarkers. Cornea. 2015;34:817–823. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Garcia JS, Rivas Jara L, Garcia-Lozano CI, et al. Ocular features and histopathologic changes during follow-up of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]