Abstract

Progressive pancreatic β-cell dysfunction is recognized as a fundamental pathology of type 2 diabetes (T2D). Recently, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been identified in protection of islets function in T2D individuals. However, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. It is widely accepted that β-cell dysfunction is closely related to improper accumulation of macrophages in the islets, and a series of reports suggest that MSCs possess great immunomodulatory properties by which they could elicit macrophages into an anti-inflammatory M2 state. In this study, we induced a T2D mouse model with a combination of high-fat diet (HFD) and low-dose streptozotocin (STZ), and then performed human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (hUC-MSCs) infusion to investigate whether the effect of MSCs on islets protection was related to regulation on macrophages in pancreatic islets. hUC-MSCs infusion exerted anti-diabetic effects and significantly promoted islets recovery in T2D mice. Interestingly, pancreatic inflammation was remarkably suppressed, and local M1 macrophages were directed toward an anti-inflammatory M2-like state after hUC-MSC infusion. In vitro study also proved that hUC-MSCs inhibited the activation of the M1 phenotype and induced the generation of the M2 phenotype in isolated mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), peritoneal macrophages (PMs) and in THP-1 cells. Further analysis showed that M1-stimulated hUC-MSCs increased the secretion of interleukin (IL)-6, blocking which by small interfering RNA (siRNA) largely abrogated the hUC-MSCs effects on macrophages both in vitro and in vivo, resulting in dampened restoration of β-cell function and glucose homeostasis in T2D mice. In addition, MCP-1 was found to work in accordance with IL-6 in directing macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 state. These data may provide new clues for searching for the target of β-cell protection. Furthermore, hUC-MSCs may be a superior alternative in treating T2D for their macrophage polarization effects.

Introduction

Progressive pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis are recognized as a fundamental pathology of type 2 diabetes (T2D)1, and accumulated evidences suggest that part of the reason is the dramatically increased macrophages within T2D islets2. For example, analysis of pancreas samples from T2D patients, Goto–Kakizaki (GK) rats, db/db mice, and C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) all showed elevated numbers of macrophages within islets3. In addition, T2D milieu characterized by high glucose and palmitate was reported to induce secretion of chemokines from islets, which promoted the infiltration of macrophages into pancreatic islets, thus leading to progression and prolongation of islets inflammation4,5.

Recent studies have revealed macrophages to be quite heterogeneous6–8. Classically activated M1-type macrophages, elicited by Th1 cytokines alone or in concert with microbial products, play a central role in host defense by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. While alternatively activated M2-type macrophages, characterized by the expression of Fizz1, CD206, and arginase-1 (Arg1), were reported to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, contributing to inflammation suppression, wound healing and tissue regeneration. Eguchi and colleagues analyzed the polarity of macrophage activation within islets using flow cytometry, and found that islet-resident macrophages largely exhibited an M2-type phenotype under basal conditions5. However, in islets of the T2D mice, the number of macrophages dramatically increased and macrophage polarity appeared to be shifted toward M1. These M1 macrophages tended to express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, subsequently resulted in progressive β-cell dysfunction and loss.

Although currently available therapeutic strategies including various oral agents and exogenous insulin can ameliorate hyperglycemia or temporarily improve insulin sensitivity, none of them can actually reverse the progressive and inexorable β-cell function damage. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a population of fibroblast-like self-renewable cells with the potential to differentiate into multiple cell types. They can be readily isolated from a variety of adult tissues and rapidly expanded ex vivo. In recent years, umbilical cord-derived MSCs (hUC-MSCs) have been spotlighted as an appealing alternative source of stem cells due to their low immunogenicity and convenience of preparation9, and the clinical efficacy of hUC-MSCs in T2D patients is quite encouraging10,11. Results from Jianxia Hu and colleagues demonstrated that during the 36-month follow-up, infusion of hUC-MSCs significantly decreased blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, and incidence of diabetic complications in T2D patients, while increasing C-peptide and homeostasis model assessment of pancreatic islet β-cell function (HOMA-β), although the precise mechanisms are yet to be elucidated10.

The primary mechanism by which MSCs ameliorate hyperglycemia was considered to be their potential to differentiate into insulin producing cells (IPCs), and a number of modified protocols have been applied to improve their differentiation efficacy12,13. Unfortunately, results in vivo were not encouraging14,15. Recently more attention has been paid to the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs16. Some recent studies indicate that MSCs could reprogram M1 macrophages into an anti-inflammatory M2 state17–20. In a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), systemically delivered hUCB-MSCs was reported to direct macrophage polarization to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis21. Work from our group also demonstrated that hUC-MSCs could elicit macrophages into an M2 state via secretion of IL-6 to alleviate insulin resistance in T2D rats22. Therefore, based on the anti-inflammatory effects of hUC-MSCs on macrophages and their therapeutic effects on islets protection10,23,24, we postulated that hUC-MSCs infusion could promote pancreatic islets recovery in T2D individuals via polarizing macrophages from M1 to an M2 phenotype.

In the present study, we induced a T2D mouse model and performed hUC-MSCs infusion. The polarization of macrophages within pancreatic islets was evaluated, and the possible mechanisms through which hUC-MSCs may modulate macrophages in terms of homeostatic immune balancing was explored.

Results

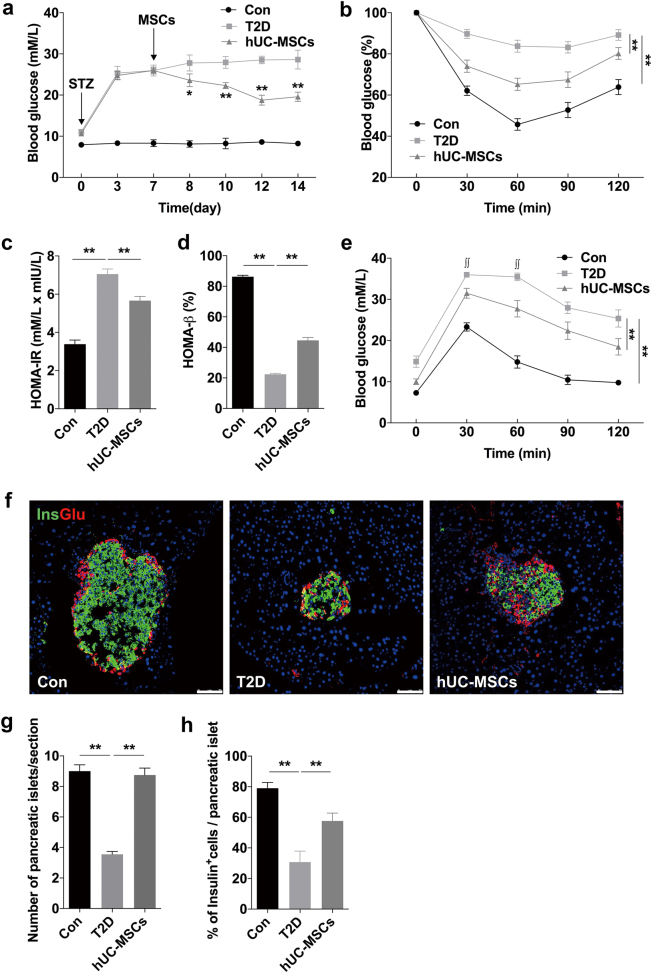

HUC-MSCs infusion improved glucose homeostasis and restored islets function in T2D mice

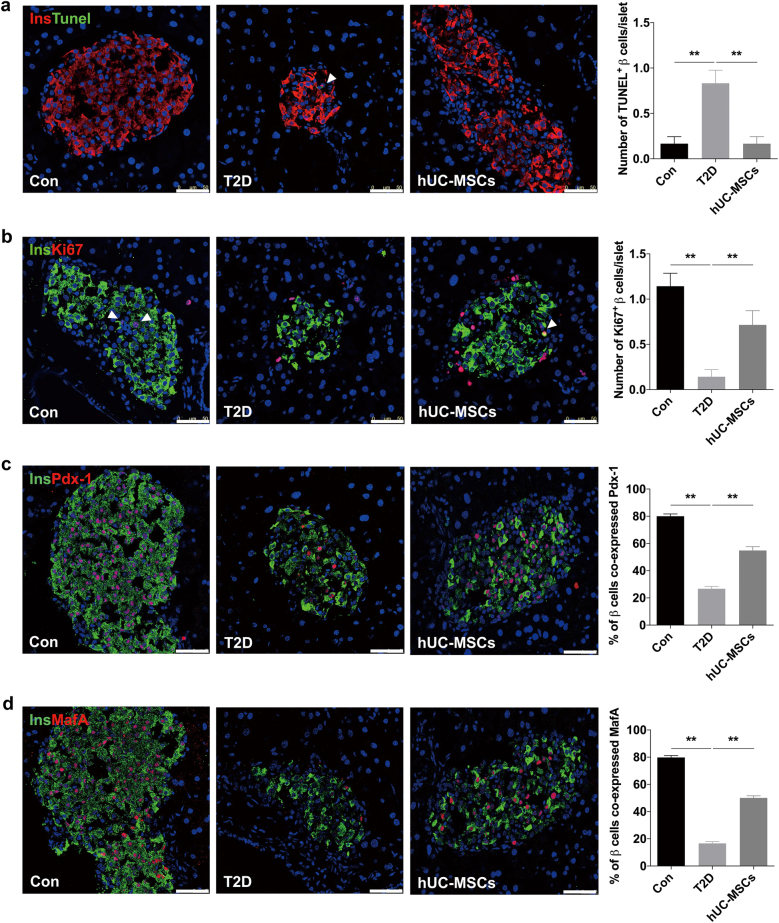

The T2D mouse model was induced by a combination of 12-week HFD and a single introperitoneal injection of low-dose streptozotocin (STZ). The 12-week HFD added more than 10 g of weight gain compared to normal chow diet (NCD) (Supplementary Fig. 1a), and the level of random blood glucose in the HFD group was 1.22 mmol/l higher than that of the NCD group (Supplementary Fig. 1b). One week after STZ administration, blood glucose in the HFD + STZ group increased to about 26 mmol/l (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (IPGTTs) (Supplementary Fig. 1d) and insulin-tolerance tests (IPITTs) (Supplementary Fig. 1e) showed significant deterioration of glucose disposal and insulin sensitivity in HFD + STZ treated mice, which confirmed the establishment of T2D model. The hUC-MSCs used in our study were isolated from human umbilical cords, and characteristics of them were identified as described previously22. As expected, hUC-MSCs infusion significantly improved glucose homeostasis in T2D mice with a gradually decreased random blood glucose level (Fig. 1a), much lower level of fasting blood glucose (FBG), and a slight increase in fasting blood insulin (FBI) (Supplementary Fig. 2). For one thing, the results of IPITT (Fig. 1b) and homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (Fig. 1c) suggested a remarkable increase in insulin sensitivity after hUC-MSCs infusion, which had been deeply investigated in our previous work22. For another, the restoration of pancreatic β-cells was indicated by the results of HOMA-β (Fig. 1d) and IPGTT (Fig. 1e), which was the focus in this paper. Histological analysis showed that islet damage including morphological disorganization, reduction in islet size and number were markedly attenuated in the mice receiving hUC-MSCs administration compared with the non-treated T2D mice (Fig. 1f, g). Moreover, systemic hUC-MSCs infusion led to significant restoration of the ratio of β-cells per islet (Fig. 1h). We also performed insulin/TUNEL and insulin/Ki67 double immunofluorescent staining to investigate the impact of hUC-MSCs on β-cell survival and proliferation. TUNEL positive β-cells were quite rare in normal control; however, one to two apoptotic β-cells could be detected in most islets of the T2D group. After hUC-MSCs infusion, the proportion of apoptotic β-cells decreased to a level comparable with that of the normal control (Fig. 2a). Ki67 staining showed that β-cells in normal control kept a low level of proliferation rate, while after HFD and STZ injection β-cell replication was severely impaired. HUC-MSCs infusion did not elicit a robust promotion of proliferation as we expected, but a certain degree of recovery was achieved (Fig. 2b). Additionally, we evaluated the expression of two key β-cell-enriched transcription factors, Pdx1 and MafA. Immunostaining showed that the ratio of β-cells co-expressing Pdx-1 downregulated from 80.25% in normal control to <30% in the T2D group, while significantly up-regulated to 54.75 in the hUC-MSCs group, consistent with the restored β-cell function we observed (Fig. 2c). Similar results were obtained with MafA (Fig. 2d). Taken together, these data demonstrated that hUC-MSCs infusion exerted remarkable therapeutic effects against T2D. Glucose homeostasis was greatly improved and islets function in T2D individuals was markedly restored.

Fig. 1. Infusion of hUC-MSCs improved glucose homeostasis in T2D mice.

The T2D mice were randomly treated with an infusion of 1 × 106 hUC-MSCs suspended in 0.2 ml PBS (referred as the hUC-MSCs group) or with an infusion of 0.2 ml PBS alone (referred as the T2D group). Mice fed with NCD served as control (referred as the Con group). a Random blood glucose level was determined consecutively after STZ injection. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus the T2D group. One week after hUC-MSCs infusion, insulin tolerance was evaluated by IPITT (b), results of which were presented relative to initial blood glucose levels. HOMA-IR (c) and HOMA-β (d) were calculated. Glucose tolerance was assessed by IPGTT (e). ∫∫, Blood glucose level exceeded the maximum (36 mmol/l) of the glucometer. f The morphology of pancreatic islets was studied by immunofluorescence according to the presence and distribution of insulin- (green) and glucagon-producing (red) cells. Scale bar, 75 μm. The number of pancreatic islets per section (g) and the percentage of insulin producing cells per islet (h) were determined by evaluating islets from at least five sections of each group. Results were presented as the means ± SD. n = 6 mice per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. T2D type 2 diabetes, hUC-MSCs human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells, PBS phosphate-buffered saline, NCD normal chow diet, STZ streptozotocin, IPITT intraperitoneal insulin-tolerance tests, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, HOMA-β homeostasis model assessment of pancreatic islet β-cell function, IPGTT intraperitoneal glucose-tolerance tests

Fig. 2. Infusion of hUC-MSCs promoted restoration of pancreatic islets function in T2D mice.

a Apoptosis of insulin producing cells (red) was evaluated by TUNEL labeling (green), and number of TUNEL+ β-cells/islet was calculated. The arrow: insulin+ cells showing TUNEL expression. b Representative islets stained with antibodies against insulin (green) and Ki67 (red) of the Con, T2D and the hUC-MSCs group. Number of Ki67+ β-cells/islet was calculated. The arrow: insulin+ cells showing Ki67 expression. c Photomicrographs double stained with anti-insulin (green) and anti-Pdx-1 (red) antibodies of the three groups. The percentage of insulin producing cells co-expressing Pdx-1 was quantified. d Photomicrographs double stained with anti-insulin (green) and anti-MafA (red) antibodies of the three groups. The percentage of insulin producing cells co-expressing MafA was quantified. Scale bar, 25 μm. Quantification was determined by evaluating islets from at least 5 sections of each group. n = 5 mice per group. The results were presented as the means ± SD. **p < 0.01. TUNEL terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

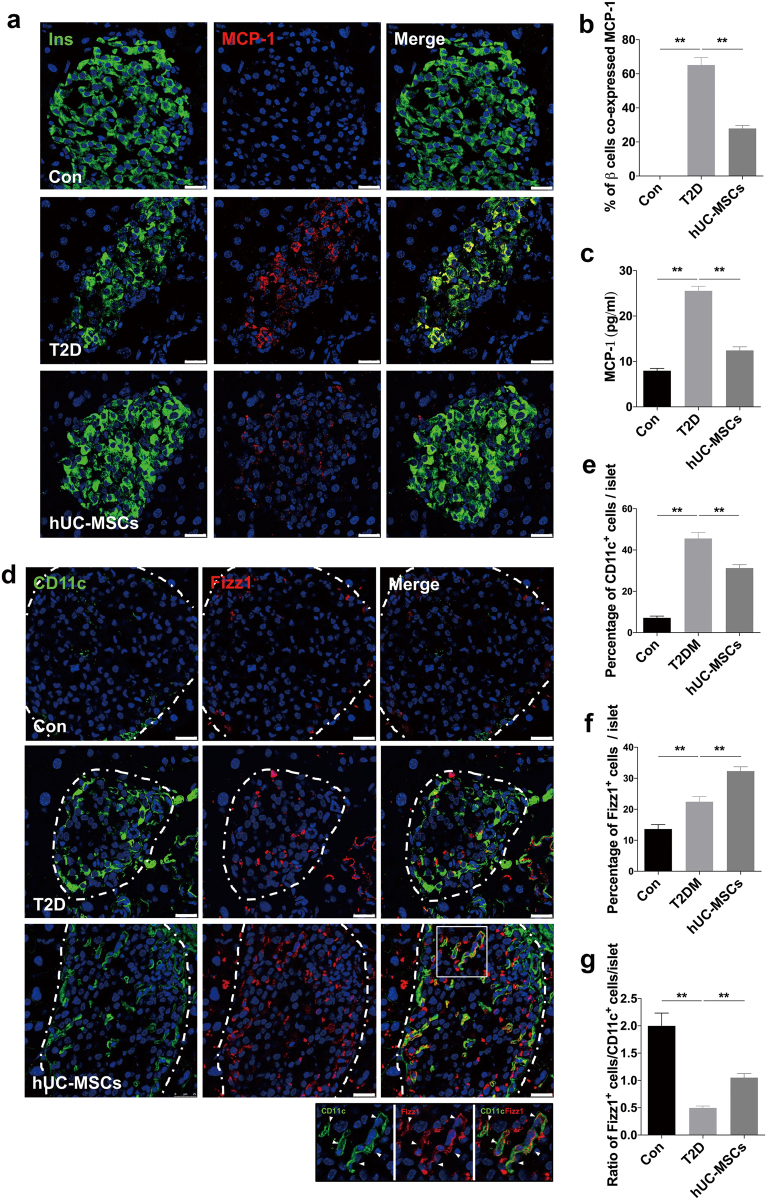

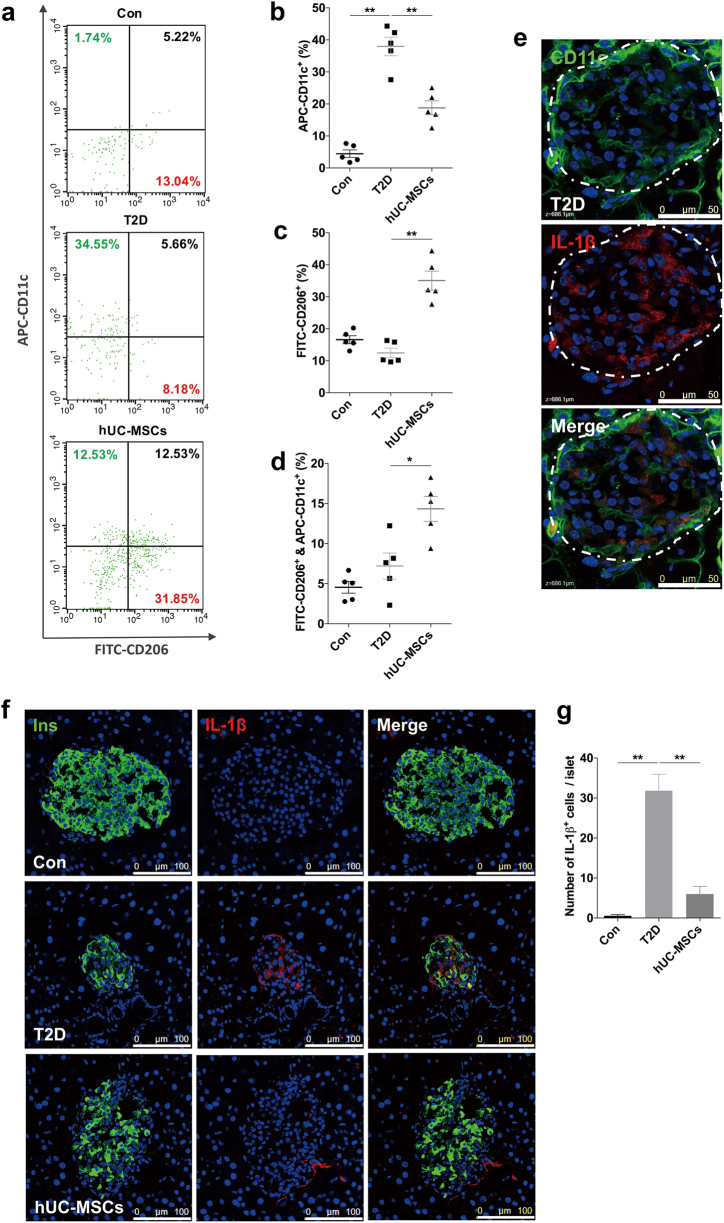

HUC-MSCs infusion suppressed inflammation and induced M2 macrophage polarization in pancreatic islets

Numbers of macrophages infiltrate in islets of T2D individuals, secreting multiple inflammatory cytokines, which is considered crucial for β-cell dysfunction. We thus investigated the effects of hUC-MSCs on macrophages in pancreatic islets. Since macrophage infiltration is reported to involve MCP-1 chemotaxis25–27, we therefore examined the expression of MCP-1 in islets. Immunostaining showed that compared with the T2D group the percentage of β-cells expressing MCP-1 was significantly downregulated after hUC-MSCs infusion (Fig. 3a, b). A similar trend was also observed in serum MCP-1 (Fig. 3c). We then used F4/80 antibody to label macrophages in islets, regardless of their sub-phenotypes. A large number of F4/80+ macrophages were detected in the T2D mice. However, despite of the lowered MCP-1 level, the amount of macrophages did not show much difference after UC-MSC infusion (Supplementary Fig 3a, 2b). Thus we speculated that the hUC-MSCs infusion might exert a regulatory role in the phenotypic distribution rather than the amount of macrophages. Immunofluorescence assay showed that macrophages in T2D islets were mainly CD11c (a marker for M1) positive, together with a slight increase in Fizz1+ (a marker for M2) cells compared with normal control. After hUC-MSCs infusion, the percentage of CD11c+ cells slightly reduced, while a dramatic increase of Fizz1+ cells within islets was observed, which led to a significant rise in the ratio of Fizz1+ cells to CD11c+ cells (Fig. 3d–g). Interestingly, CD11c/Fizz1 double-positive cells were quite noticeable in islets of the hUC-MSCs group (Fig. 3d). These results suggested that hUC-MSCs could induce M2 macrophage polarization in pancreatic islets of T2D mice, and this was further supported by the results form flow cytometry analysis for CD11c and CD206 (a marker for M2) (Fig. 4a–d) as well as the immunostaining of iNOS+ (a marker for M1), CD163 and ARG1 (markers for M2) (Supplementary Fig 4a-c). No significant difference was detected in the amount of pancreatic VEGF+ cells between the T2D and the hUC-MSCs group (Supplementary Fig 4d). Accompanied by the changes in macrophage distribution, the expression of IL-1β, which was mainly secreted by M1 macrophages (Fig. 4e), was highly expressed in T2D mice, but could only be detected in very few of the macrophages after hUC-MSCs infusion (Fig. 4f, g). Blood serum levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, which were upregulated after HFD and STZ administration, were downregulated by hUC-MSCs treatment (Supplementary Fig 5a-c). Serum IL-10, an anti-inflammatory molecule, was slightly increased in the hUC-MSCs group (Supplementary Fig 5d). No statistical difference was found in IL-4 (Fig. 4l) among the three groups (Supplementary Fig 5e). In summary, these data indicate that hUC-MSCs infusion could induce M2 macrophage polarization in pancreatic islets and effectively alleviate the chronic inflammation in T2D individuals.

Fig. 3. HUC-MSCs significantly downregulated the expression of MCP-1 in β-cells and induced M2 macrophage polarization in pancreatic islets.

a Photomicrographs of representative islets stained with anti-insulin (green) and anti-MCP-1 (red) antibodies from the Con, T2D, and the hUC-MSCs group. Percentage of insulin+ cells expressing MCP-1was shown in b. c Serum level of MCP-1 was determined by AimPlex™ assay. d Photomicrographs of representative islets stained with anti-CD11c (green) and anti-Fizz1 (red) antibodies from the Con, T2D, and the hUC-MSCs group. The dotted line circled areas are pancreatic islets. The boxed region showed CD11c and Fizz1 double positive cells within islets, enlarged drawings of which were shown at the bottom of the image. Quantifications of CD11c+ cells and Fizz1+ cells within islets were separately presented in e and f. Ratio of Fizz1+ cells/CD11c+ cells was calculated and presented in g. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 5 mice per group. The results were presented as the means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. MCP-1 monocyte chemotactic protein 1

Fig. 4. HUC-MSCs infusion induced M2 macrophage polarization and suppressed inflammation in pancreatic islets.

a For flow cytometry analysis, freshly obtained pancreases were dissected and digested into the pellets, which were then incubated with F4/80-PE, CD11c-APC, and CD206- FITC antibodies. F4/80+ cells were selected for CD11c+ and CD206+ screening, proportions of which were shown in b and c, respectively. The proportion of CD11c+ and CD206+ double-positive cells were shown in d. e Photomicrographs of representative islet stained with anti-CD11c (green) and anti- IL-1β (red) antibodies from the T2D group. The dotted line circled area is pancreatic islet. Scale bar, 50 μm. f Photomicrographs of representative islets stained with anti-insulin (green) and anti-IL-1β (red) antibodies from the three groups. Scale bar, 100 μm. Quantification of IL-1β+ cells was shown in g and determined by evaluating islets from at least five sections of each group. PE phycoerythrin, APC allophycocyanin, FITC fluorescein isothiocyanate, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor α

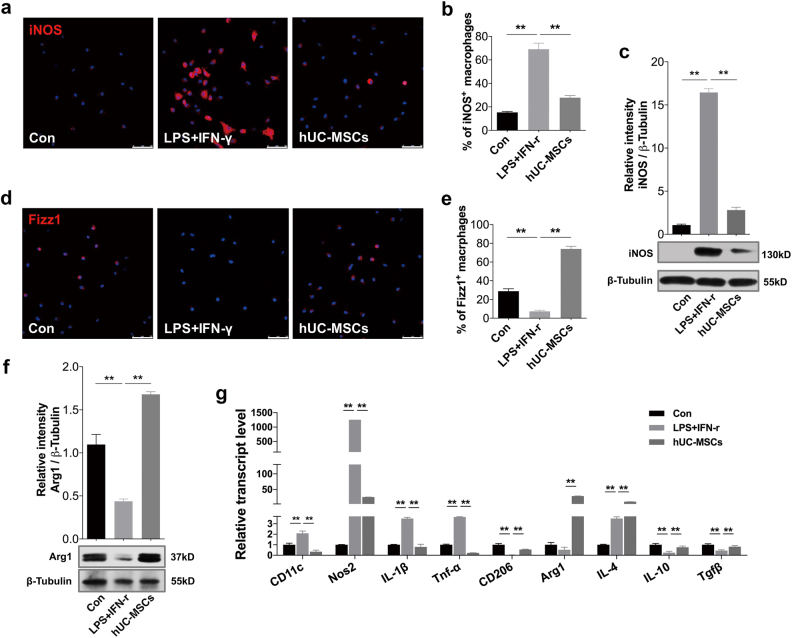

HUC-MSCs suppressed the activation of M1 macrophages and induced the generation of M2 macrophages in vitro

Next, we sought to confirm the modulatory effects of hUC-MSCs on the phenotype of macrophages in vitro. Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) and peritoneal macrophages (PMs) were isolated. Flow cytometry analyses showed that the positive rate of F4/80 in the bone marrow-derived cells was over 95% (Supplementary Fig. 6a). And immunofluorescence detection revealed that about 93% of the cells achieved by peritoneal lavage were F4/80 positive (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were used to induce BMDMs and PMs to polarize towards M1 phenotype. The stimulated BMDMs and PMs were then co-cultured with hUC-MSCs in a trans-well system for 24 h. In comparison with the LPS- and IFN-γ-stimulated group, the expression of iNOS was significantly down-regulated in the hUC-MSCs co-cultured group (Fig. 5a–c). Results of immunofluorescence from PMs (Fig. 5a, b), and immunoblotting (Fig. 5c) from BMDMs all supported this trend. Meanwhile, the protein expression of Fizz1 (in PMs) (Fig. 5d, e) and Arg1 (in BMDMs) (Fig. 5f), markers for M2 macrophages, were significantly upregulated after hUC-MSCs co-culture. Consistently, quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed higher expression of genes encoding M2 macrophages (CD206 and Arg1) and anti-inflammatory mediators (IL-4, IL-10, and Tgfβ) in the hUC-MSCs co-cultured BMDMs compared with the LPS- and IFN-γ-stimulated BMDMs, while lower expression of genes encoding M1 macrophages (CD11c, Nos2) and pro-inflammatory molecules (IL-1β and TNF-α) (Fig. 5g). Moreover, the secretion of cytokines in the supernatant of BMDMs were measured by AimPlex multiplex assay, results of which showed that the levels of IL-1β (Supplementary Fig 7a) and TNF-α (Supplementary Fig 7b) significantly decreased after hUC-MSCs incubation, and the level of IL-4 increased (Supplementary Fig 7c). Additionally, to address the issue that hUC-MSCs could influence to “human” macrophages, THP-1 cells was stimulated by LPS and IFN-γ (Supplementary Fig 8) or a combination of cytokines including IAPP, CCL2, CXCL1, and IL-1β (to mimic microenvironment of T2D pancreas) (Supplementary Fig 9) and then co-cultured with hUC-MSCs. The results from RT-PCR, ELISA, immunofluorescent staining, and cytometry analysis demonstrated that hUC-MSCs could inhibit classical M1 activation and convert macrophages into an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype through paracrine mechanism.

Fig. 5. HUC-MSCs suppressed the activation of M1 macrophages and induced the generation of M2 macrophages in vitro.

BMDMs and PMs were cultured alone (Con group) or in stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ in the absence (LPS + IFN-γ group) or presence of hUC-MSCs co-culturing (hUC-MSCs group). a Immunofluorescence of iNOS+-PMs in the three groups. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification of iNOS+-PMs presented in b was determined by evaluating at least five random fields of each section. c Immunoblotting analysis of iNOS in BMDMs. Relative protein level is quantified by ratio of iNOS to β-tubulin. d Immunofluorescence of Fizz1+-PMs in the three groups. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification of Fizz1+ PMs presented in e was determined by evaluating at least five random fields of each section. f Immunoblotting analysis of Arg1 in BMDMs. Relative protein level is quantified by ratio of Arg1 to β-tubulin. g Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of gene expression in BMDMs from the three groups. Results are presented relative to those of the control group, set as 1. Values are means ± SD of three individual experiments, **p < 0.01. BMDMs bone marrow-derived macrophages, PMs peritoneal macrophages, LPS lipopolysaccharides, IFN- γ interferon- γ, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase, Arg1 arginase-1, RT-PCR reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, Nos2 nitric oxide synthase 2, Tgfβ transforming growth factor-β

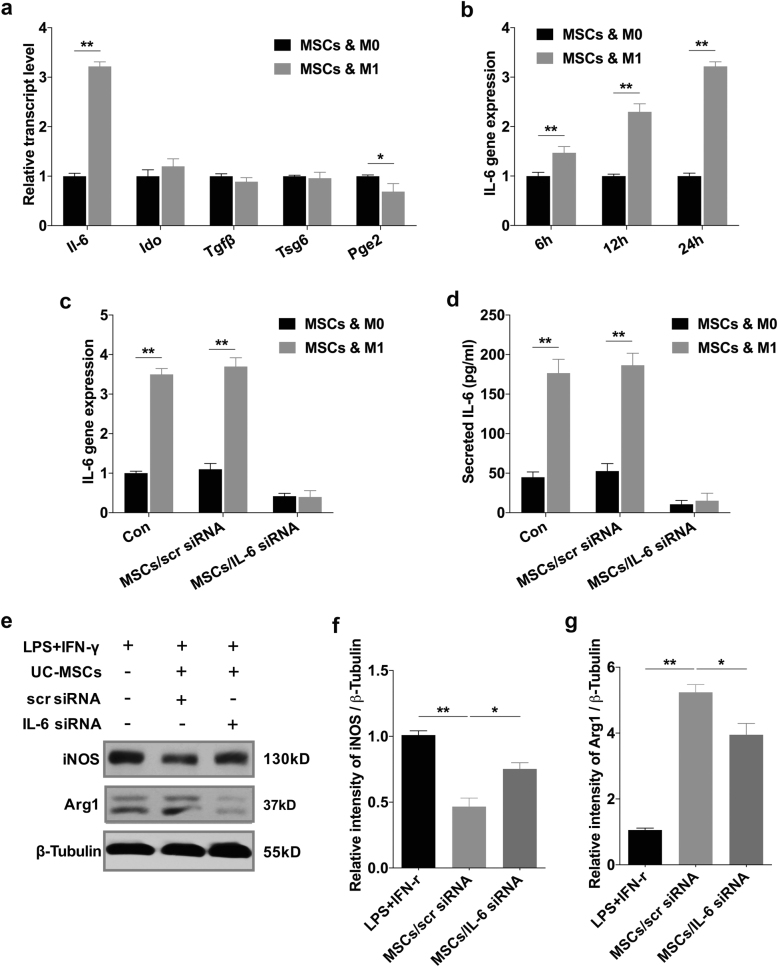

HUC-MSCs modulated macrophage polarization via secretion of IL-6

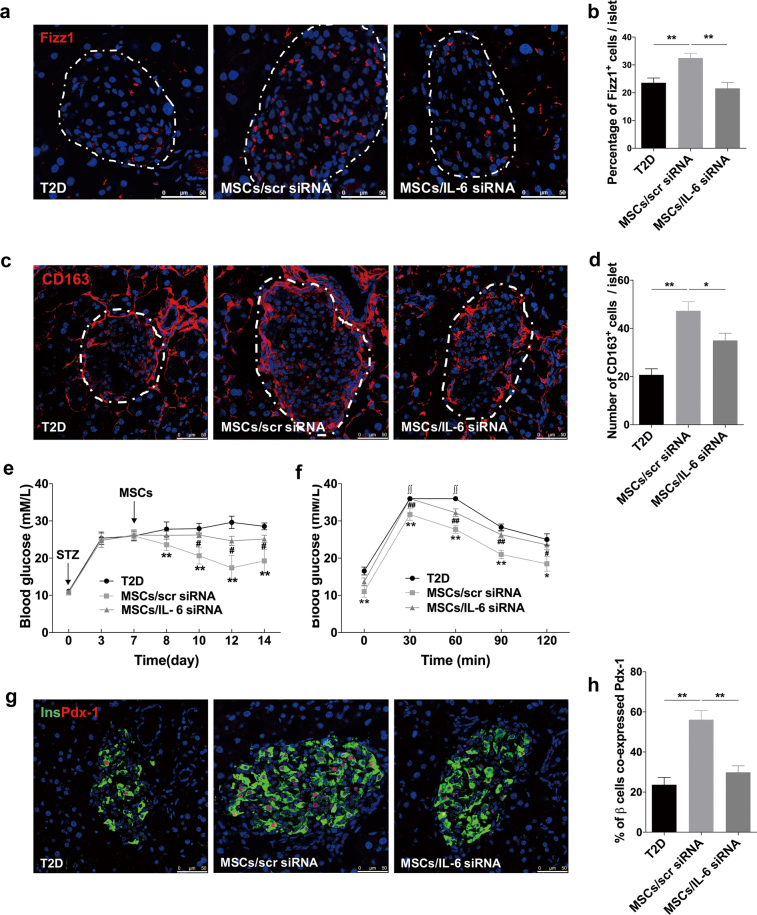

Given that immunomodulatory effects of MSCs are reported to be non-instinctive but rather initiated by inflammatory mediators28–30, we hypothesized that the disease-specific inflammatory microenvironment may affect the regulatory effects of hUC-MSCs. Therefore, we evaluated the expression changes of several crucial immunomodulatory factors in hUC-MSCs after they were co-cultured with M1 BMDMs. These immunomodulatory factors include IL-6, indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (Ido), transforming growth factor-β (Tgfβ), TNF-α-induced protein 6 (Tsg6), and prostaglandin E2 (Pge2), which are reported to involve in polarization modulatory effects of MSCs on macrophages16,22,31. The results showed that no significant difference was detected in the expression of Ido, Tgfβ, and Tsg6. A slight decrease was observed in the gene encoding Pge2, whereas only the expression of IL-6 was significantly increased (Fig. 6a). Further research showed that IL-6 expression in hUC-MSCs gradually and continuously upregulated within 24-h incubation (Fig. 6b, c), and the secretion level of IL-6 in the supernatants increased to as high as 176.6 pg/ml (Fig. 6d). In vivo, IL-6 and hUC-MSCs co-staining was also observed in hUC-MSCs-treated T2D mice (Supplementary Fig 10). We thus inhibited IL-6 in hUC-MSCs using small interfering RNA (siRNA). Transcription (Fig. 6c) and secretion (Fig. 6d) levels of IL-6 were significantly reduced by IL-6 siRNA. The results of immunoblotting analysis revealed that hUC-MSCs transfected with the scrambled siRNA (scr siRNA) significantly decreased the expression of iNOS, and increased that of Arg1 in BMDMs, whereas the effect of hUC-MSCs transfected with IL-6 siRNA on regulating the expression of iNOS and Arg1 was partially abrogated (Fig. 6e–g). Consistently, our in vivo study on Fizz1+ cells (Fig. 7a, b), CD163+ cells (Fig. 7c, d) and CD11c+ cells (Supplementary Fig 11a, b) revealed that the effect of hUC-MSCs on modulating macrophage phenotype in pancreatic islets was also dampened after transfected with IL-6 siRNA. As expected, the therapeutic effects of hUC-MSCs on glucose homeostasis and islets protection were impaired, which were indicated by the results of random blood glucose (Fig. 7e), IPGTT (Fig. 7f), and expression of PDX-1 in β-cells (Fig. 7g, h). All together, these data demonstrated that hUC-MSCs regulate macrophage polarization at least partially through IL-6 secretion, resulting in restoration of β-cell function and glucose homeostasis.

Fig. 6. HUC-MSCs modulated macrophage polarization via secretion of IL-6 in vitro.

a Relative gene expression levels of immunomodulatory factors involve in polarization modulatory effect of hUC-MSCs on macrophages. hUC-MSCs were cultured with primary BMDMs (M0) or with LPS- and IFN-γ-stimulated BMDMs (M1) for 24 h. Results are presented relative to those of hUC-MSCs cultured with M0, set as 1. b Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of IL-6 expression in hUC-MSCs. HUC-MSCs were cultured with M0 or M1 for 6, 12, 24 h, results are presented relative to those of hUC-MSCs cultured with M0, set as 1. c Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of IL-6 expression in hUC-MSCs (Con), hUC-MSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA (MSCs/scr siRNA), or hUC-MSCs with IL-6 siRNA (MSCs/IL-6 siRNA). HUC-MSCs were cultured with M0 or with M1. d Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) of IL-6 in medium of hUC-MSCs cultured with M0 or M1, symbols are as in c. e Immunoblotting analysis of BMDMs in stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ cultured alone, cultured with hUC-MSCs transfected with scr siRNA, or with hUC-MSCs transfected with IL-6 siRNA. Relative protein level is quantified by ratio of iNOS to β-tubulin and that of Arg1 to β-tubulin, and separately shown in f and g. Values are means ± SD of three individual experiments, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. IL-6 interleukin 6, Ido indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase. Tsg6 TNF-α-induced protein 6, Pge2 prostaglandin E2

Fig. 7. HUC-MSCs modulated macrophage polarization via secretion of IL-6 in vivo.

Photomicrographs of representative islets stained with anti-Fizz1 (red) (a) and anti-CD163 (red) (c) antibodies from the T2D mice without (T2D group) or with the administration of hUC-MSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA (MSCs/scr siRNA group) or hUC-MSCs transfected with IL-6 siRNA (MSCs/IL-6 siRNA group). The dotted line circled areas are pancreatic islets. Quantifications of Fizz1+ cells and CD163+ cells within islets were determined by evaluating islets from at least five sections of each group, results of which were separately presented in b and d. e Blood glucose level was determined consecutively after STZ injection. Values are means ± SD. **p < 0.01 for the MSCs/scr siRNA group versus the T2D group. #p < 0.05 for MSCs/IL-6 siRNA group versus the MSCs/scr siRNA group. f Glucose tolerance was assessed by IPGTT. ∫∫, blood glucose level exceeded the maximum (36 mmol/l) of the glucometer. g Photomicrographs double stained with anti-insulin (green) and anti-Pdx-1 (red) antibodies of the three groups. The percentage of insulin-producing cells co-expressing Pdx-1 was quantified by evaluating islets from at least five sections of each group, results of which were shown in h. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 5 mice per group. The results were presented as the means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

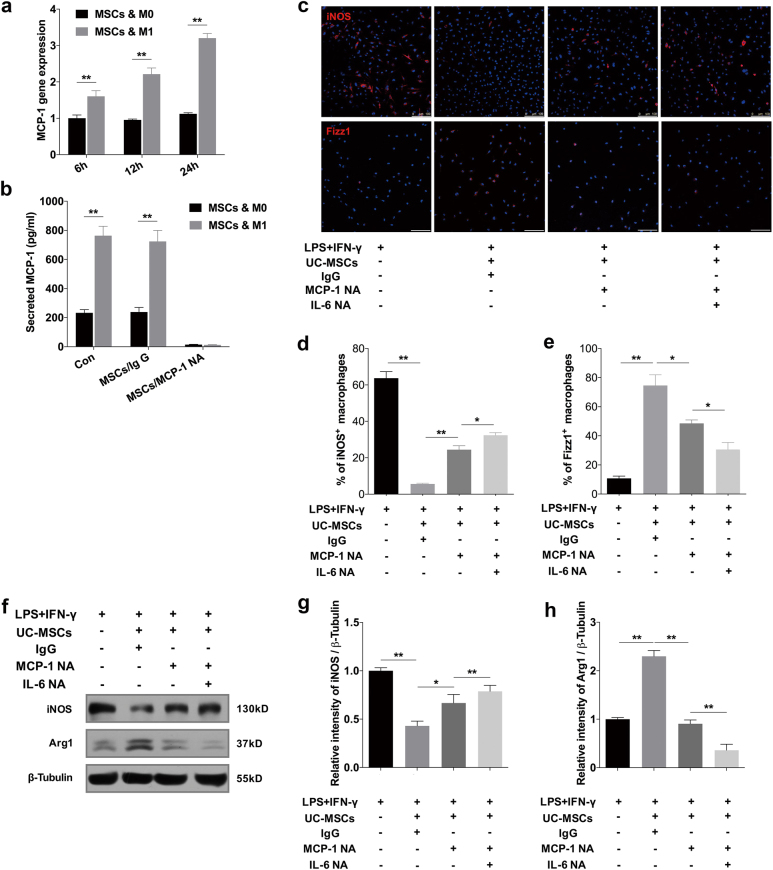

HUC-MSCs secreted MCP-1 to coordinate with IL-6 in regulating macrophage polarization

Considering there is evidence demonstrating the role of MCP-1 in coordinating with IL-6 in inducing M2-type macrophage polarization32, we further investigated the expression of MCP-1 in hUC-MSCs. It was found that the mRNA expression of MCP-1 in hUC-MSCs significantly increased after co-cultured with M1 BMDMs (Fig. 8a). Accordingly, the level of MCP-1 secreted by hUC-MSCs rose to nearly 800 pg/ml in the cultured medium (Fig. 8b). To verify the role of MCP-1 in hUC-MSCs, MCP-1 neutralizing antibody (NA) was added in the medium to block MCP-1 secreted by hUC-MSCs. IgG served as the control condition. After neutralization, the concentration of MCP-1 in supernatant was reduced to lower than 15 pg/ml (Fig. 8b). With this extreme low level of MCP-1, we found that the expression of iNOS greatly increased, while that of Fizz1 and Arg1 significantly decreased at protein level according to the immunofluorescence (Fig. 8c–e) and immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 8f–h). Together with MCP-1 NA, we also neutralized IL-6 by IL-6 NA, after which the concentration of IL-6 was reduced to less than 5 pg/ml. The results showed that expression of iNOS was further increased while expression of Fizz1 and Arg1 was further decreased, which indicated that simultaneous blocking of MCP-1 and IL-6 led to greater inhibition to the modulatory role of hUC-MSCs (Fig. 8c–h). These data suggested that MCP-1 and IL-6 secreted by hUC-MSCs could work in accordance to direct macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 state.

Fig. 8. HUC-MSCs secreted MCP-1 to coordinate with IL-6 in regulating macrophage polarization.

a Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of MCP-1 expression in hUC-MSCs. HUC-MSCs were cultured with M0 or M1 for 6, 12, 24 h. Results were presented relative to those of UC- MSCs cultured with M0, set as 1. b Secretory level of MCP-1 in medium of hUC-MSCs (Con), hUC-MSCs conditioned with IgG (MSCs/IgG) or hUC-MSCs conditioned with MCP-1 neutralizing antibody (NA) (MSCs/MCP-1 NA). HUC-MSCs were cultured with M0 or with M1. c Immunofluorescence of iNOS+-BMDMs and Fizz1+-PMs in stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ cultured alone, with hUC-MSCs conditioned with IgG, hUC-MSCs conditioned with MCP-1 neutralizing antibody (NA), or hUC-MSCs conditioned with MCP-1 neutralizing antibody (NA) plus IL-6 NA. Scale bar, 100 μm. Quantification of iNOS+ BMDMs and Fizz1+ PMs were presented in d and e. f Immunoblotting analysis of iNOS and Arg1 in BMDMs of the same four groups mentioned in c. Relative protein level is quantified by ratio of iNOS to β-tubulin g and that of Arg1 to β-tubulin h. Values are means ± SD of three individual experiments, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Discussion

Macrophages within islets are known to influence β-cell function, proliferation, and apoptosis. Under normal physiological conditions, macrophages are constitutively present within islets, where they provide a suitable microenvironment for β-cell development and the maintenance of islet homeostasis33,34. However, during the progression of T2D, fatty acids stimulate pancreatic β-cells to produce chemokines that promote intra-islet accumulation of M1 macrophages5,25, and together with other TLR2/6 and TLR4 ligands stimulate the secretion of proinflammatory factors such as IL-1β from macrophages35. As IL-1β receptor is abundantly expressed on β-cells36, the high concentration of IL-1β subsequently suppresses both proliferation of β-cells and their secretion of insulin37, even lead to β-cell apoptosis38,39. However, emerging evidences have revealed a role for M2 macrophages during β-cell protection, repair, and regeneration. Upon helminth infection, an important TH2 response is induced, with an alteration in macrophage phenotype from M1 to M240. The helminth infection increases islet infiltration of M2 macrophages, which results in reduced insulitis and β-cell loss, thus preventing the onset of diabetes in HFD41, non-obesity diabetes (NOD)42, and multiple low dose STZ-treated mice43. Another report shows that M2 macrophages recruited to the pancreas after partial duct ligation (PDL) promotes β-cell proliferation by secreting TGFβ and epidermal growth factor44. In our study, we found that HFD and STZ not only induced intra-islet accumulation of M1 macrophages, but also elicited a slight increase in the number of M2 macrophages. This was similar to the finding observed in db/db mice where the increased M2 macrophages were suggested to be contributed by a systemic shift from M1 macrophages45. However, the moderately increased M2 macrophages seem not sufficient to reverse the proinflammatory microenvironment. After hUC-MSCs infusion, a significantly increased proportion of M2 macrophages occurred in the pancreas, accompanied by a downregulation in that of M1 macrophages and reduced expression of proinflammatory mediators. After knockdown of IL-6, the effects of hUC-MSCs on macrophage phenotype modulation was dampened, meanwhile, therapeutic effects of hUC-MSCs on islets protection was greatly impaired.

In our study, we found that MCP-1 expression in islets was remarkably reduced after hUC-MSCs infusion, but the number of macrophages in islets did not change significantly. This may be due to that macrophage recruitment mainly occurred in the early phase of islets damage, as the number of intra-islet macrophages of T2D group changed little at third and fifth week following the STZ injection compared with that at second week after the injection (data not shown). Besides, in addition to MCP-1, macrophages have other chemotactic mechanisms. Studies have shown that macrophages trafficking from the bone marrow mainly depend on the chemokine receptor CCR2 and its ligand MCP-146, while migration of spleen leukocyte is mediated by angiotensin II (AT-2) released from impaired tissues and AT-2 receptor-1α (ATR-1α) expressed on monocytes and macrophages47. In our previous study, we found that a large number of hUC-MSCs homed to spleen after infusion, accompanied with increased M2-like macrophages in the spleen (data not shown). These M2-like macrophages are likely to mobilized in large numbers to the site of tissue injury47–49, and in this case, the injured tissue could be the pancreas. Another possibility could be local macrophage proliferation in the injured pancreas. In steady state50 and PDL51, resident macrophages were reported to proliferate in a macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)-dependent manner. And MSCs have been demonstrated to promote proliferation of macrophages via secreting M-CSF52.

IL-6 and MCP-1 are often considered to be pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with progression of T2D53,54. However, emerging studies have suggested that these two factors can modulate macrophages toward an M2-like state. MCP-1, together with Siglec-9, are indicated to improve acute liver failure by altering macrophage polarity in rats55. Our own work demonstrated that IL-6 secreted by hUC-MSCs could elicit macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue, thereby alleviating insulin resistance in T2D rats22. The different inflammatory properties of these two cytokines revealed in different studies may be related to diverse concentration, utility duration, and complex mechanisms on different cell types. In addition, whether the increased MCP-1 and IL-6 in inflammation-related diseases is the cause or manifestation of tissue injury still needs further exploration.

In conclusion, hUC-MSCs treatment restored islets function in T2D mice, and this effect was partially attributed to suppressing inflammation and inducing M2 macrophages polarization via the secreted MCP-1 and IL-6 from hUC-MSCs. These data may provide new clues for searching for the target of protecting islet β-cell function, and provide a theoretical basis for hUC-MSCs use in the clinic as a treatment.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of hUC-MSCs

HUC-MSCs were isolated from human umbilical cords freshly obtained from women who gave birth in the Chinese PLA General Hospital. All of the subjects provided informed consent. The characteristics of hUC-MSCs were identified by phenotypes and the potential to differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts22. Protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. For selective knockdown of IL-6, hUC-MSCs were transfected with siRNA for IL-6 (IL-6 siRNA) (GenePharma, Suzhou, China) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, NY, USA). hUC-MSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA (scr siRNA) (GenePharma, Suzhou, China) served as control. The protocol and sequences for IL-6 siRNA and scr siRNA were described previously22. For neutralization experiments, 50ug/ml IL-6 NA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and/or 5 μg/ml MCP-1 NA (R&D Systems) were added to the cultured medium when hUC-MSCs were co-culturing with M1 BMDMs. To confirm successful knockdown or blockade of IL-6 and MCP-1, RNA and/or cultured medium of hUC-MSCs were obtained to measure the expression of IL-6 and/or MCP-1 by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

T2D induction and treatment

8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice purchased from the Chinese PLA General Hospital were fed with HFD (60% fat, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or a normal chow diet (NCD) for 12 weeks. To achieve T2D model, a single dose of 100 mg/kg STZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5), was intra-peritoneally injected to HFD-fed mice. Blood glucose levels were determined by monitoring tail capillary blood glucose levels with a glucometer (Yuwell, Jiangsu, China). One week after STZ administration, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (IPGTTs) and insulin-tolerance tests (IPITTs) were applied to confirm the T2D model. For IPGTT or IPITT, overnight fasted mice were intra-peritoneally injected with glucose (1.5 g/kg) or insulin (1 U/kg), glucose levels of which were determined by tail blood samples taken every 30 min up to 120 min. The established T2D mice were then randomly treated with an infusion of 1 × 106 hUC-MSCs suspended in 0.2 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (referred as the hUC-MSCs group) through the tail vein or with an infusion of 0.2 ml PBS alone (referred as the T2D group). In order to demonstrate the homing of hUC-MSCs in pancreas, a random collection of T2D mice were treated with hUC-MSCs labeled with chloromethyl-benzamidodialkylcarbocyanine (CM-Dil, Life technologies, Eugene, Oregon, USA) in advance according to the manufacturer’s instruction. One week later, IPGTT and IPITT were performed again to assess the therapeutic effects of hUC-MSCs. Blood plasma was obtained. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was detected in the Biochemistry Department of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. Fasting blood insulin (FBI) was measured by commercial ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and for β-cells (HOMA- β) were calculated by the following equation: (FBG [in mmol/l] × FBI [in mIU/l])/22.5, 20× FBI [in mIU/l]/(FBG [in mmol/l]−3.5) (%). All in vivo experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the medical ethics committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital.

Generation and stimulation of macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages (PM) were achieved from 6-week-old C57BL/6J male mice by peritoneal lavage with 2 ml RMPI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), and then cultured in RMPI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Gibco). Identification of PMs were done by anti-F4/80 (1:50, Life technologies, Frederick, USA) immunofluorescence. BMDMs were isolated from the femur and tibia of 6-week-old C57BL/6J male mice and then cultured in RMPI 1640 supplemented with 100 ng/ml M-CSF (R&D system), 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin streptomycin. Identification of BMDMs were done by anti-F4/80 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA, Clone:BM8) flow cytometry. Lipopolysaccharides (100 ng/ml, LPS, Sigma-Aldrich) and interferon-γ (50 ng/ml, IFN-γ, R&D Systems) were added in the medium to stimulate the two types of macrophages for 24 h. The macrophages were then cultured with 5 × 104 hUC-MSCs in a trans-well system for another 24 h.

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin streptomycin at a density of 3 × 105–6 × 105 cells/ml as recommended by the ATCC. The differentiation was induced by treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 160 ng/ml, Sigma). After 24 h, the non-adherent cells were removed with three rinses with PBS. Adherent cells were further incubated with fresh medium containing LPS(100 ng/ml) and IFN-γ(50 ng/ml, Prime Gene Bio-Tech, Shanghai, China) or combined cytokines including IAPP (0.1 μM/ml, Prime Gene Bio-Tech), CCL2 (10 ng/ml, Prime Gene Bio-Tech), CXCL1 (10 ng/ml, Prime Gene Bio-Tech) and IL-1β (10 ng/ml, Prime Gene Bio-Tech) for 24 h. After that, conditioned medium was removed and incubated with fresh medium alone or together with hUC-MSCs by trans-well for another 36 h.

Flow cytometric analysis

Freshly obtained pancreases were rinsed in PBS, and then minced into little pieces. Tissues were digested in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solutions (HBSS) (TBD, Tianjin, China) with 2 mg/ml V collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10–15 min at 37 ℃ with shaking. D-HBSS (TBD, Tianjin, China) was added to terminate the digestion and the cell suspensions were filtered through a 400-mesh metal filter and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The pellets were then incubated with PE-conjugated anti F4/80 (eBioscience), FITC-conjugated anti-CD206 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA Clone: C068C2) and APC-conjugated anti-CD11c (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) antibodies for flow cytometry analysis.

Freshly harvested BMDM were washed twice and then stained with PE-conjugated anti F4/80 (eBioscience) antibody for flow cytometry analysis. The THP-1 cells were washed twice before incubated with fix&perm and perm (BD), and them stained with PE-conjugated anti CXCL-10 (eBioscience) antibody for flow cytometry analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining

Mice were sacrificed at indicated time points, for which 1% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) was intra-peritoneally injected, and then 10 ml PBS was perfused through the left ventricle followed with 15 ml 4% paraformaldehyde. After the perfusion, pancreases were isolated and incubated in 30% sucrose/PB overnight. The tissues were then embedded with optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT, Sakura, Finetek, USA) and made into frozen sections at 6 μm. For immunofluorescence analysis, frozen sections were blocked in bovine serum albumin and incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies of insulin (1/200, guinea pig, Abcam, San Francisco, USA), Glucogon (1/2000, mouse, Abcam), TUNEL (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), Ki67 (1:300, rabbit, Abcam), PDX-1 (1:300, rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology), MafA(1:200, rabbit, Bethyl Laboratories), MCP-1 (1:100, rabbit, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), IL-1β (1:100, rabbit, Abcam), F4/80 (1:50, mouse, Life Technologies), CD11c (1:100, mouse, Abcam), Fizz1 (1:100, rabbit, Abcam,), iNOS (1:250, rabbit, Abcam), CD163 (1:200, mouse, Bio-rad, CA, USA), ARG1 (1:100, rabbit, Abcam), VEGF (1:100, rabbit, ZENBIO, China), IL-6 (1:100, rabbit, Abcam), CD206 (1:100, rabbit, Abcam), then with Alexa Fluor 488/594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1: 500, Life technologies) at room temperature for 2 h. The nuclei were visualized with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich). The sections were observed under laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). PMs and THP-1 cells were plated onto glass coverslips and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. The following steps were performed as described above.

Cytokine profile

HUC-MSCs were co-cultured with PM or BMDM for 24 h, after which the culture supernatant was harvested. The secretion of IL-6 and MCP-1 from hUC-MSCs was measured using commercial ELISA kits from NeoBioscience, Shenzhen, China. The secretion of IL-1β, Tnf-α, and IL-4 from BMDM were quantified by AimPlex™ assay kits (QuantoBio, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer instruction, together with mouse blood serum MCP-1, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α. Levels of IL-1β and IL-10 in the supernatant of THP-1 cells were also evaluated by ELISA kits from NeoBioscience, Shenzhen, China.

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from BMDM, and the experiment was carried out as described previously56. The primary antibodies were iNOS (1:1000, rabbit, Abcam), Arg1 (1:1000, rabbit, Abcam), and β-Tubulin (1:2000, mouse, ZSGB-Bio, Beijing, China). The secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit, and rabbit anti-mouse IgG horse radish peroxidase (HRP) (1:3000, mouse, ZSGB-Bio). The blots were analyzed using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA samples were extracted from BMDM, THP-1 cells, and hUC-MSCs using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), and then reversely transcribed to single-stranded cDNA with a reverse transcription kit (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA) according to the instructions. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed on ABI Prism thermal cycler model StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) using a SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Bio-systems). The thermal cycling program was 94 ℃ for 3 min, followed by 94 ℃ for 30 s, 60 ℃ for 30 s and 72 ℃ for 30 s for 40 cycles. Melting curve analysis was included to ensure primer specificity. Gapdh was used as the internal control. The primers were listed in Supplementary Table 1 and 2.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as means ± SD from at least three independent samples. Differences between means were assessed using a Student’s t test or Chi-square test when required. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 14.0.1 (SPSS Inc., IBM).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank technical assistance from Zhiqiang Wu, Hanren Dai, Dongdong Ti, Xiang Li, Jie Bai, Bing Li, Xiaolei Li, Liang Dong, and other members of the Mu and Han laboratories for insightful discussions over this work. This work was supported in part by the National Basic Science and Development Program [81700679] and [81700680], and the 863 Projects of Ministry of Science and Technology of China [2013AA020105] and [2012AA020502].

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yaqi Yin, Haojie Hao, Yu Cheng, Li Zang

Edited by E. Baehrecke

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-018-0801-9).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Weidong Han, Email: hanwdrsw69@yahoo.com.

Yiming Mu, Email: muyiming@301hospital.com.cn.

References

- 1.Butler AE, et al. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eguchi K, Nagai R. Islet inflammation in type 2 diabetes and physiology. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:14–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI88877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehses JA, et al. Increased number of islet-associated macrophages in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2356–2370. doi: 10.2337/db06-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cnop M. Fatty acids and glucolipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of Type 2 diabetes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36(Pt 3):348–352. doi: 10.1042/BST0360348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eguchi K, et al. Saturated fatty acid and TLR signaling link beta cell dysfunction and islet inflammation. Cell. Metab. 2012;15:518–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray PJ, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batsali AK, Kastrinaki MC, Papadaki HA, Pontikoglou C. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from Wharton’s Jelly of the umbilical cord: biological properties and emerging clinical applications. Curr. Stem. Cell. Res. Ther. 2013;8:144–155. doi: 10.2174/1574888X11308020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu J, et al. Long term effect and safety of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells on type 2 diabetes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016;12:1857–1866. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong D, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transfusion ameliorated hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Lab. 2014;60:1969–1976. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2014.140305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh SH, et al. Adult bone marrow-derived cells trans-differentiating into insulin-producing cells for the treatment of type I diabetes. Lab. Invest. 2004;84:607–617. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriscot C, et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can express insulin and key transcription factors of the endocrine pancreas developmental pathway upon genetic and:or microenvironmental manipulation in vitro. Stem Cells. 2005;23:594–604. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lechner A, et al. No evidence for significant transdifferentiation of bone marrow into pancreatic β-cells in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:616–623. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JB, et al. Little evidence of transdifferentiation of bone marrow-derived cells into pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1366–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma S, et al. Immunobiology of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:216–225. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson P, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells induce immunomodulatory macrophages which protect from experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut. 2013;62:1131–1141. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayan V, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells mediate a switch to alternatively activated monocytes/macrophages after acute myocardial infarction. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 2011;106:1299–1310. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: a novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Exp. Hematol. 2009;37:1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ylostalo JH, Bartosh TJ, Coble K, Prockop DJ. Human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells cultured as spheroids are self-activated to produce prostaglandin E2 that directs stimulated macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2283–2296. doi: 10.1002/stem.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin TH, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-stem cells direct macrophage polarization and block inflammasome activation to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2524. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie Z, et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells elicit macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype to alleviate insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic rats. Stem Cells. 2016;34:627–639. doi: 10.1002/stem.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Si Y, et al. Infusion of mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic rats: identification of a novel role in improving insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2012;61:1616–1625. doi: 10.2337/db11-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao H, et al. Multiple intravenous infusions of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells reverse hyperglycemia in experimental type 2 diabetes rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;436:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin AP, et al. Increased expression of CCL2 in insulin-producing cells of transgenic mice promotes mobilization of myeloid cells from the bone marrow, marked insulitis, and diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:3025–3033. doi: 10.2337/db08-0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rull, A., Camps, J., Alonso-Villaverde, C. & Joven, J. Insulin resistance, inflammation, and obesity: role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (or CCL2) in the regulation of metabolism. Mediators Inflamm.2010, 1–11, 326580 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ren G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Chen X, Cao W, Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/ni.3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nemeth K, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat. Med. 2009;15:42–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo JH, Bazhanov N, Kuhlman J, Prockop DJ. Dynamic compaction of human mesenchymal stem/precursor cells into spheres self-activates caspase-dependent IL1 signaling to enhance secretion of modulators of inflammation and immunity (PGE2, TSG6, and STC1) Stem Cells. 2013;31:2443–2456. doi: 10.1002/stem.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roca H, et al. CCL2 and interleukin-6 promote survival of human CD11b+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells and induce M2-type macrophage polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34342–34354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geutskens SB, Otonkoski T, Pulkkinen MA, Drexhage HA, Leenen PJ. Macrophages in the murine pancreas and their involvement in fetal endocrine development in vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;78:845–852. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1004624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banaei-Bouchareb L, et al. Insulin cell mass is altered in Csf1op/Csf1op macrophage-deficient mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:359–367. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nackiewicz D, et al. TLR2/6 and TLR4-activated macrophages contribute to islet inflammation and impair beta cell insulin gene expression via IL-1 and IL-6. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1645–1654. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boni-Schnetzler M, et al. Free fatty acids induce a proinflammatory response in islets via the abundantly expressed interleukin-1 receptor I. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5218–5229. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Muayed M, et al. Acute cytokine-mediated downregulation of the zinc transporter ZnT8 alters pancreatic beta-cell function. J. Endocrinol. 2010;206:159–169. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maedler K, et al. Low concentration of interleukin-1beta induces FLICE-inhibitory protein-mediated beta-cell proliferation in human pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2006;55:2713–2722. doi: 10.2337/db05-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suarez-Pinzon W, et al. Beta-cell destruction in NOD mice correlates with Fas (CD95) expression on beta-cells and proinflammatory cytokine expression in islets. Diabetes. 1999;48:21–28. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kreider T, Anthony RM, Urban JF, Jr., Gause WC. Alternatively activated macrophages in helminth infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007;19:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu D, et al. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science. 2011;332:243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1201475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Q, et al. Helminth infection can reduce insulitis and type 1 diabetes through CD25- and IL-10-independent mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:5347–5358. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01170-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Espinoza-Jimenez A, Rivera-Montoya I, Cardenas-Arreola R, Moran L, Terrazas LI. Taenia crassiceps infection attenuates multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010;2010:850541. doi: 10.1155/2010/850541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao X, et al. M2 macrophages promote beta-cell proliferation by up-regulation of SMAD7. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E1211–E1220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321347111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cucak H, Grunnet LG, Rosendahl A. Accumulation of M1-like macrophages in type 2 diabetic islets is followed by a systemic shift in macrophage polarization. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014;95:149–160. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsou CL, et al. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swirski FK, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiroyoshi T, et al. Splenectomy protects the kidneys against ischemic reperfusion injury in the rat. Transpl. Immunol. 2012;27:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wystrychowski W, et al. Splenectomy attenuates the course of kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Transplant. Proc. 2014;46:2558–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hashimoto D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Gassen N, et al. Macrophage dynamics are regulated by local macrophage proliferation and monocyte recruitment in injured pancreas. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;45:1482–1493. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takizawa N, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells propagate immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory macrophages in cell-to-cell contact-independent and -dependent manners under hypoxic culture. Exp. Cell Res. 2017;358:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:98–107. doi: 10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim HJ, et al. Differential effects of interleukin-6 and -10 on skeletal muscle and liver insulin action in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:1060–1067. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito T, et al. Secreted ectodomain of SIGLEC-9 and MCP-1 synergistically improve acute liver failure in rats by altering macrophage polarity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44043. doi: 10.1038/srep44043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Q, et al. M2 macrophages infusion ameliorates obesity and insulin resistance by remodeling inflammatory/macrophages’ homeostasis in obese mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017;443:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.