Abstract

The mainstay in prevention and treatment of aspergillosis is the use triazole drugs. In Kenya, the use of agricultural azole is one of the predisposing factors in development of resistance. One hundred fifty-six (156) experienced soils were collected from agricultural farms and cultured on Sabouraud DextroseAagar. The study isolated 48 yielded Aspergillus fumigatus and 2 A. flavus. All the isolates were subjected to antifungal susceptibility testing against three triazoles: posaconazole, voriconazole, and itraconazole. Out of the isolates, 3 had MIC of 32 and 1 had MIC of 16 against itraconazole, and 1 isolate had MIC of 32 against posaconazole. CYP51A gene was sequenced, and TR34/L98H mutation was identified. Triazole resistance existing in Kenya calls for rational use of azole-based fungicides in agriculture over concerns of emerging antifungal resistance in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Aspergillus species, especially Aspergillus fumigatus, is the most common cause of aspergillosis, which is the second leading cause of death after cryptococcosis in patients suffering from fungal infections [1]. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus is an evolving global health challenge [2]. It is a frequent colonizer of cavitary lesions in tuberculosis patients and cause of mortality in post-TB treatment cases [3].

Aspergillosis treatment is done by using amphotericin B or azoles. However, resistance against azoles has been increasingly reported especially from high- and middle-income countries [4–12]. Previous studies from different regions of the world—African region (Tanzania), European region (Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, and Germany), Asia (Kuwait, India, and Iran), and the USA—have reported multiple sources of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus from soil sample, flower beds, plants, compost, and hospitals and its environs [4, 10, 12–23].

In contrast, limited data are available from low-income countries, especially from sub-Saharan Africa. However, a recent disturbing report of high resistance to azole was reported in Moshi, Tanzania associated with A. fumigatus with TR34/L98H and TR46/Y12F/T289A mutations [20]. The widespread irrational use of azole-based agricultural fungicides in the flower and horticultural industry in Kenya is a significant risk factor for azole resistance. The study aimed to determine the prevalence of triazole resistance among Aspergillus fumigatus from fungicide-experienced soils.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

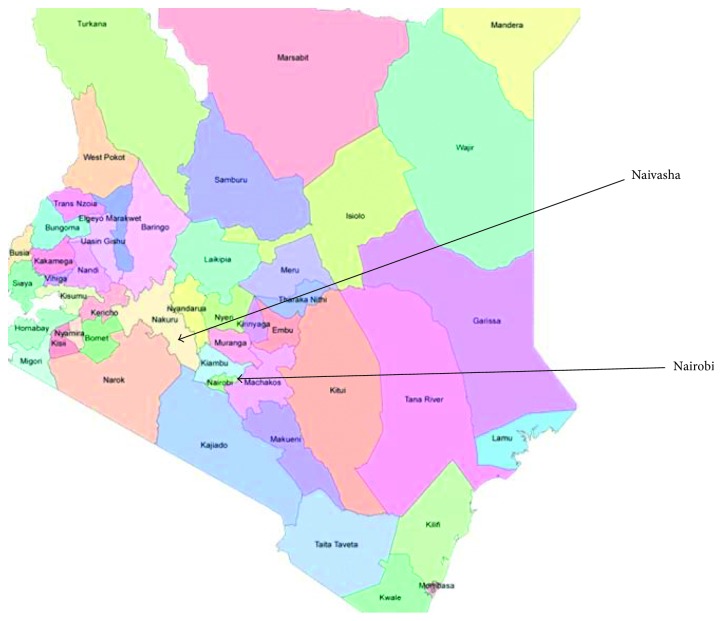

The study was conducted in Nairobi and Naivasha subcounty where horticultural practices and green houses are concentrated. Nairobi is the capital city of Kenya and lies at about 1°17′S and 36°49′E while Naivasha is located approximately 90 km northwest of Nairobi. It is located in Nakuru County at 0°43′S36°26E, and horticulture is the main economy. The trade names of commonly used fungicides include milraz, antracol, mistress, and victory which are broad-spectrum fungicides of ornamental, vegetable, and fruit plants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A map showing the study areas. Courtesy of www.mapsofworld.com (accessed 12 January 2015).

2.2. Sampling for Environmental Isolates

A total of 156 samples were collected and analyzed. Approximately 5 g dry top surface soil from the agricultural site was collected into a sterile 15 ml Falcon tube using a sterile plastic spoon [23]. Samples were transported in a leak-proof packaging in a cool box to the Mycology Laboratory-KEMRI-Center for Microbiology Research for investigation. Clinical isolates were isolated from sputum samples of suspected aspergillosis patients and were archived at Kenya Medical Research Institute, Mycology Laboratory.

2.3. Fungal Culture and Identification

One gram of soil sample was mixed with 5 ml saponin, vortexed, and the debris was allowed to settle. One hundred microliters of the supernatant was transferred to 500 µl of sterile normal saline and vortexed. Approximately 100 µl of the suspension was cultured onto Sabouraud dextrose agar containing (a). 0.001 mg/l of itraconazole, (b) 0.001 mg/l of voriconazole, and (c) without drug (control). All the inoculated plates were incubated for 5 days at 30°C [24].

2.4. Broth Dilution Sensitivity Testing

Aspergillus fumigatus growing on azole-supplemented media were subjected to antifungal susceptibility testing against three triazoles: posaconazole (PCZ), voriconazole (VCZ), and itraconazole (ITZ) using the CLSI M38-A2 broth microdilution method [25].

2.5. Sequencing of CYP51A Gene

Aspergillus fumigatus showing high MIC against itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole had their CYP51A gene sequenced for detection of mutation as previously described [26].

3. Results

A total 156 fungicide-exposed soil samples were analyzed, out of which 48 yielded Aspergillus fumigatus and 2 A. flavus. Antifungal susceptibility testing against three triazoles, posaconazole, voriconazole, and itraconazole, indicates that 3 isolates had MIC = 32 µg/ml and other 2 had MIC = 4 µg/ml against itraconazole, 5 isolates had MIC = 8 µg/ml and 1 isolate had MIC = 16 µg/ml against voriconazole, and 1 isolate had MIC of 32 µg/ml and one had MIC = 16 µg/ml against posaconazole (Table 1). Two archived clinical Aspergillus fumigatus from KEMRI-Mycology were used for comparison (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sources of isolates and MIC against the three triazoles.

| Number | Sources | Isolates | MIC against itraconazole | MIC against voriconazole | MIC against posaconazole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| F2 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F3 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| F4 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| F5 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F6 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| F7 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| F8 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F9 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| F10 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| F11 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| F12 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| F13 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| F14 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| F15 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F16 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| F17 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.13 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| F18 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| F19 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| F20 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F21 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| F22 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.5 |

| F23 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 32 | 8 | 0.5 |

| F24 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| F25 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 8 | 0.5 |

| F26 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| F27 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| F28 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 1 | 0.15 |

| F29 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F30 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| F31 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F32 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| F33 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| F34 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F35 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| F36 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 32 | 16 | 1 |

| F37 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| F38 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| F39 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| F40 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 32 | 8 | 32 |

| F41 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| F42 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| F43 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| F44 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| F45 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | 8 | 0.5 |

| F46 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.25 | 0.006 | 0.25 |

| F47 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| F48 | Experienced soils | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.5 |

| C21 | Clinical | Aspergillus fumigatus | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| C40 | Clinical | Aspergillus fumigatus | 2 | 1 | 0.13 |

Triazole resistance levels of all of the Aspergillus fumigatus isolates are summarized in Table 2. According to Arendrup et al. [27] breakpoints, the percentage of resistance against both itraconazole and voriconazole was 12.5% and susceptible cases at 87.5% and 85.4% against itraconazole and voriconazole, respectively. Against posaconazole, 27.1% were resistant, 60.4% were intermediates, and 12.5% were susceptible.

Table 2.

Triazole resistance levels of the isolated Aspergillus fumigatus.

| Resistance | Itraconazole (n (%)) | Voriconazole (n (%)) | Posaconazole (n (%)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant | 6 (12.5) | 6 (12.5) | 13 (27.1) |

| Intermediates | 0 | 1 (2.08) | 29 (60.4) |

| Susceptible | 42 (87.5) | 41 (85.4) | 6 (12.5) |

| Total | 48 (100) | 48 (100) | 48 (100) |

Three samples with high MIC were subjected to sequence analysis for the detection of mutation in CYP51A in which TR34/L98H was confirmed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sequencing analysis of CYP51A of selected Aspergillus fumigatus.

| Number | Mutation | STRS | Sources | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F36 | A. fumigatus | TR34/L98H | 14 | 21 | 8 | 32 | 9 | 38 | 8 | 10 | 18 | Environmental |

| F40 | A. fumigatus | TR34/L98H | 14 | 21 | 8 | 28 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 18 | Environmental |

| C21 | A. fumigatus | TR34/L98H | 14 | 21 | 8 | 28 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 18 | Clinical |

4. Discussion

In our study, we report the presence of triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus from clinical- and fungicide-experienced soils collected from Naivasha and Nairobi, Kenya. Azole-resistant Aspergillus spp. have been detected worldwide including Asia, Europe, Middle East, Tanzania [20], and Kenya. Kemoi et al. reported prevalence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus between 19.23% and 36% from both naive and experience soils. However, the study did not sequence CYP51A gene to determine the type of mutations involved [21]. The finding of this study is of great medical implications especially in African environments where resources are limited and effective treatment and early diagnosis are a challenge. Posaconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole are the first-line drugs used in management and prevention of aspergillosis; hence, detection of environmental isolates resistant to these triazoles poses great challenge in the medical field [27, 28].

In Kenya, Naivasha subcounty is known for extensive flower farming with extensive use of fungicides. The use of azole-based fungicide in agriculture introduces antifungal pressure resulting in reduced susceptible fungi and increases azole-resistant strains [29]. Detection of A. fumigatus with TR34/L98H mutation is the first report in Kenya. It has been reported by several authors that isolates with mutations in TR34/L98H region have cross resistance to both medical azole and azole-based fungicides, for example, propiconazole, tebuconazole, difenoconazole, bromuconazole, and epoxiconazole [4, 12]. The TR34/L98H mutation in gene CYP51A involves the substitution of leucine 98 for histidine L98H and two 34-bp tandem copies in CYP51A gene in the promoter region [10, 30–33].

Azole-based fungicides in the environment have been linked to TR/L98H mutation in Aspergillus fumigatus. This form of resistance has been linked to point alteration in 220, 138, and 54 codons from patient on azole treatment [34]. Plant pathogenic molds having tandem repeat which aid in resistance against sterol demethylation inhibitor fungicides have been reported [35]. Because fungi including A. fumigatus and other plant fungal pathogens share the same habitat, they are constantly exposed to fungicide pressure. Therefore, if Aspergillus species harboring TR/L98H resistance is present in the environment, the conidia can be widely dispersed by wind and may cause infection in the susceptible individual [9].

In Moshi, Tanzania, Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated from soil known for extensive farming. It was reported that 20% of the environmental samples harbor azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus, of which 5.5% was associated with TR46/Y122FT289A mutation and 20% TR34/L98H mutation was isolated from woody debris and soil samples [20]. The isolation of Aspergillus fumigatus with G54E mutation in Tanzania, Romania, and India from environmental samples is considered to occur in patients with prolonged exposure to azole [36]. The G54E mechanisms are responsible for 20.0% from India, 30.4% from Romania, and 46.4% of resistant isolates from Tanzania [36].

5. Conclusion

There is significant triazole resistance among environmental isolates of Aspergillus probably ascribed to irrational use of fungicide in agriculture and calls for legislative mechanism for control of fungicide use. This is a grave public health concern given the limited resources and the limited antifungal options available for the susceptible patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI IRG Grant no. INNOV/IGR/019/2).

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institute and Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (KEMRI/SERU/P000602/3031). There was no human participation or direct human contact. However, approved permission to access the farms was obtained from relevant institution or flower farms owner or individual farm owner.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brown G. D., Denning D. W., Gow N. A. R., Levitz S., Netea M., White T. Human fungal infections: the hidden killers. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:165–167. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeulen E., Maertens J., Schoemans H. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation emerging in Belgium. Euro Surveillance. 2012;17:203–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denning D. W., Pleuvry A., Cole D. C. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;89(12):864–872. doi: 10.2471/blt.11.089441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chowdhary A., Kathuria S., Randhawa H. S., Gaur S. N., Klaassen C. H., Meis J. F. Isolation of multiple triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67(2):362–366. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bueid A. Azole antifungal resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus 2008 and 2009. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2010;65(10):2116–2118. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgel P. R., Baixench M. T., Amsellem M., et al. High prevalence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in adults with cystic fibrosis exposed to itraconazole. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012;56(2):869–874. doi: 10.1128/aac.05077-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lockhart S. R., Frade J. P., Etienne K. A., Pfaller M. A., Diekema D. J., Balajee S. A. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2011;55(9):4465–4468. doi: 10.1128/aac.00185-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortensen K. L., Mellado E., Lass-Florl C., Rodriguez-Tudela J. L., Johansen H. K., Arendrup M. C. Environmental study of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigates and other aspergilli in Austria, Denmark, and Spain. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54(11):4545–4549. doi: 10.1128/aac.00692-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mortensen K. L., Jensen R. H., Johansen H. K., et al. Aspergillus species and other molds in respiratory samples from patients with cystic fibrosis: a laboratory-based study with focus on Aspergillus fumigatus azole resistance. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2011;49(6):2243–2251. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00213-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snelders E., Van der L. H., Kuijers J., et al. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219.e219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snelders E., Venselaar H., Schattenaar G., Karawajczyk A., Verhoum R. J. A. The structure-function relationship of the Aspergillus fumigatus Cry51A L98H conversion by site-directed mutagenesis: the mechanism of L98H azole resistance. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2011;48(11):1062–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snelders E., Camps S. M., Karawajczyk A., et al. Triazole fungicides can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS One. 2012;7(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031801.e31801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad S., Khan Z., Hagen F., Jacques F. M. Simple, low-cost molecular assays for TR34/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene for rapid detection of triazole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52(6):2223–2227. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00408-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad S., Joseph L., Hagen F., Meis J. F., Khan Z. Concomitant occurrence of itraconazole resistant and susceptible stains of Aspergillus fumigatus in routine cultures. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2015;70(2):412–415. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad S., Khan Z., Hagen F., Meis J. F. Occurrence of triazole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus with TR34/L98H mutations in outdoor and hospital environment in Kuwait. Environmental Research. 2014;133:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiederhold N. P., Gil V. G., Gutierrez F., et al. First detection of TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A cyp51 mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in the United States. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2016;54(1):168–171. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02478-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu M., Zeng R., Zhang L., et al. Multiple cyp51A based mechanism identified in azole resistant isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus from China. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2015;59(7):4321–4325. doi: 10.1128/aac.00003-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nabili M., Badiee P., Moazeni M., et al. High prevalence of clinical and environmental triazole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Iran: is it a challenging issue? Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2016;65(6):468–475. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badali H., Vaezi A., Haghani I., et al. Environmental study of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus with TR34/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in Iran. Mycoses. 2013;56(6):659–663. doi: 10.1111/myc.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowdhary A., Sharma C., van den Boom M., et al. Multi azole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the environment in Tanzania. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2014;69(11):2979–2983. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemoi E. K., Nyerere A., Gross U., Bader O., Gonoi T., Bii C. C. Diversity of azole resistant Aspergillus species Isolated from experience and naïve soils in Nairobi County and Naivasha Sub-County, Kenya. European Scientific Journal. 2017;13(36) doi: 10.19044/esj.2017.v13n36p301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermeulen E., Maertens J., Bel A. D., et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2015;59(8):4569–4576. doi: 10.1128/aac.00233-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader O., Weig M., Reichard U., et al. Cyp51A based mechanism of Aspergillus fumigatus azole drug resistance present in clinical samples from Germany. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57(8):3513–3517. doi: 10.1128/aac.00167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bader O., Tunnermann J., Dudakova A., Tangwattanachuleeporn M., Weig M., Gross U. Environmental isolates of azole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Germany. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2015;59(7):4356–4359. doi: 10.1128/aac.00100-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snelders E., Huis in’t Veld R. A. G., Rijis J. M. M. A., Kema G. H. J., Melchers W. J. G., Verweiji P. E. Possible environmental origin of resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus to medical triazoles. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(12):4053–4057. doi: 10.1128/aem.00231-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi—Second Edition: Standard M38–A2. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arendrup M. C., Cuenca-Estrella M., Lass-Flord C., Hope W. W. European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing subcommittee on antifungal testing. EUCAST technical note on Aspergillus and Amphotericin B, itraconazole and posaconazole. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(7):E248–E250. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chowdhary A., Kathuria S., Xu J. Clonal expansion and emergence of environmental multiple triazole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR34/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052871.e52871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verweji E. P., Kema H. G., Melchers J. W. Triazole fungicides and the selection of resistance to medical triazoles in the opportunistic mould Aspergillus fumigatus. Pest Management Science. 2013;69(2):165–170. doi: 10.1002/ps.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdolrasouli A., Rhodes J., Beale M. A., et al. Genomic context of azole resistance mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus determined using whole-genome sequencing. MBio. 2015;6(4) doi: 10.1128/mbio.00939-15.e00536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellado E., Garcia-Effron G., Alcazar-Fuoli L., et al. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of CYP51A alterations. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2007;51(6):1897–1904. doi: 10.1128/aac.01092-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Linden J. W., Snelders E., Kampinga G. A., et al. Clinical implication of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands, 2007-2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17(10):1846–1854. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shapiro R. S., Robbins N., Cowen L. E. Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance and disease. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2011;75(2):213–267. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00045-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arendrup M. C., Mavridou E., Mortensen K. L., et al. Development of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy associated with change in virulence. PLoS One. 2010;5(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010080.e10080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snelders E., Melchers W. J., Verweij P. E. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a new challenge in the management of invasive aspergillosis? Future Microbiology. 2011;6(3):335–347. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma C., Hagen F., Moroti R., Meis J. F., Chowdhary A. Triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus harbouring G54 mutation: is it de novo or environmentally acquired? Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2015;3(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]