Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify the role of the precursor of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (pro-BDNF) in myocardial hypoxia/reoxygenation injury (H/R) and to address the underlying mechanisms. For this purpose, myocardial microvascular endothelial cells (MMECs) exposed to a high concentration of glucose (30 mM) for 48 h were subjected to 4 h of hypoxia followed by 2 h of reoxygenation. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining and flow-cytometric analysis were performed to detect apoptosis. Cell scratch and capillary-like-structure formation assays were employed to evaluate cell function. The levels of apoptosis-related proteins were evaluated by Western blotting and immunofluorescence assays. Our results showed that H/R resulted in MMEC injury, as indicated by significant increases in TUNEL-positive cell numbers and a reduction in MMEC migration and in capillary-like-structure formation coupled with increased pro-BDNF protein expression. In addition, overexpression of pro-BDNF in MMECs via a viral vector led to increased pro-BDNF expression, and this upregulation induced apoptosis. Mechanistic experiments revealed that H/R did not influence BDNF, JNK, and caspase 3 expression, but upregulated pro-BDNF, p75NTR, sortilin, phospho-JNK, and cleaved caspase 3 protein levels. In contrast, neutralization of endogenous pro-BDNF with an antibody significantly attenuated H/R-induced upregulation of pro-BDNF, p75NTR, sortilin, p-JNK, and cleaved caspase 3 protein levels, indicating that p75NTR-sortilin signaling and activation of JNK and caspase 3 may be involved in these effects. In conclusion, H/R-induced injury may be mediated by pro-BDNF, at least in part through the regulation of p75NTR-sortilin signaling and activation of JNK and caspase 3.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a potent and prevalent risk factor of ischemic heart disease, has received increasing attention globally. Cardiovascular complications constitute the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with DM [1–4]. In addition, DM increased myocardial susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion- (I/R-) caused irreversible destruction, characterized by deficient oxygen supply and subsequent restoration of blood flow [5–8]. Microvascular disturbances are a vital feature of myocardial reperfusion injury [9]. Myocardial I/R is associated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis, infiltration by immune cells, an inflammatory cytokine release, and angiogenesis [10–12]. Cardiac microvascular endothelial cells, a basic component of myocardial microcirculation, were first harmed by reperfusion injury followed by damage to cardiomyocytes after restoration of the cardiac microcirculation and played a vital role in the preservation of cardiomyocytes after reperfusion injury [9, 13]. Moreover, numerous studies have shown that endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction, an important event in virtually all forms of I/R injury, determines the degree of cellular injury after I/R [14]. Nevertheless, the potential mechanisms responsible for the adverse effects caused by apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction after endothelial injury induced by hyperglycemia with I/R insults remain an enigma.

In recent years, studies on the nerve growth factor (NGF) family have been focused on the nervous system [15]. Lately, a large number of studies confirmed that this family also has an important role in the cardiovascular system [16]. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a member of the NGF family, has been shown to have an antiapoptotic effect against the toxicity of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in human microvascular ECs [17]. Pro-BDNF, a precursor of BDNF, has been originally described as a proapoptotic ligand in the nervous system. Thus, it is believed that pro-BDNF may exert proapoptotic action on ECs [18, 19].

Both ECs and endothelial progenitor cells express high-affinity receptors called Trk [20]. NGF and BDNF promoted the growth and angiogenesis of ECs through their high-affinity receptors (TrkA and TrkB) [21]. Besides, NGF promoted the survival and functional recovery of cardiomyocytes after myocardial I/R injury via paracrine pathways [22]. P75NTR, a low-affinity receptor for neurotrophins, is involved in a diverse array of cellular responses, including apoptosis. Sortilin is known as a coreceptor of p75NTR, and its deficiency is reported to reduce apoptosis [23]. The actions of pro-BDNF are mediated by a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin [24]. Pro-BDNF with high affinity for p75NTR may be deeply involved in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (MIRI). c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is indispensable for both cell proliferation and apoptosis. However, the molecular mechanism that underlies the participation of pro-BDNF in the process of endothelial I/R-induced apoptosis has not been elucidated completely.

JNK, one of the members of the MAP kinase superfamily, is primarily involved in the induction of death receptor-initiated exogenous and mitochondrial apoptosis in vivo after exposure to various chemical or biological agents [25]. JNK activated apoptotic signaling pathways by transactivation of specific transcription factors or by modulating the activity of mitochondrial proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins directly through different phosphorylation events, thereby increasing proapoptotic gene expression [26]. Activated JNK, in turn, phosphorylated c-Jun and proteins associated with apoptosis such as caspase 3 [27]. Caspase 3 activity is a biochemical hallmark of apoptosis, and imaging the activity is a part of an assay in an apoptosis-targeted treatment response in cancer [28]. Regulation of the activity of the JNK signaling pathway is vital for protecting myocardial cells from I/R injury [29, 30].

Currently, there is no evidence that pro-BDNF participates in the process of endothelial I/R injury, and the corresponding molecular mechanism is unclear. In the present study, we investigated the role of pro-BDNF in the regulation of hypoxia/reoxygenation- (H/R-) induced endothelial apoptosis, migration, and tube formation and next examined the expression of proteins related to apoptosis. These findings will lead to a novel therapeutic approach for myocardial I/R injury.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The human myocardial microvascular endothelial cell (MMEC) line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and maintained in the DMEM high-glucose complete medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% of CO2 at 37°C. MMECs (passages 3 to 5), characterized by typical cobblestone appearance and by positive CD31 and CD34 immunostaining [31], were used for the following experimental analysis.

2.2. H/R Injury Induction

To induce H/R injury as described previously [32], an I/R model was established by means of MMECs. The cells were incubated in a high-glucose culture medium (30 mM) for 48 h and then exposed to hypoxia (5% CO2, 1% O2, and 94% N2) for 4 h followed by 2 h of reoxygenation (5% CO2, 21% O2, and 94% N2).

2.3. Viral-Vector Transduction of MMECs and Antibody Neutralization

The recombinant adenoviruses expressing the human pro-BDNF gene (Ad-GFP-pro-BDNF) or GFP control (Ad-GFP) were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China) and were used to infect the ECs according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transduction efficiency was verified via GFP expression and Western blotting. The neutralizing antibody to the recombinant prodomain of BDNF (10 μg/mL), specifically recognizing pro-BDNF but not mature BDNF or other neurotrophins, was added into the culture medium prior to induction of H/R [33–36].

2.4. Apoptosis Assay

Apoptosis was detected by the TUNEL assay (Roche Applied Science) and by corresponding flow-cytometric analyses according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For quantification, the TUNEL-positive cells were counted in at least five randomly chosen visual fields in three independent samples (500 counted cells in total). The flow-cytometric assay was then performed on a BD FACSCalibur instrument (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Lake Franklin, NJ, USA).

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

This analysis was conducted to determine the protein expression and phosphorylation levels. Cellular proteins were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Proteins (lysate corresponding to 20 μg of protein) were loaded onto a gel and separated in each lane by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) lasting for 2 h at 100 V in a buffer and were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After blocking in 5% fat-free dry milk, antibodies against pro-BDNF (Alomone, 1 : 400), BDNF (Abcam, 1 : 500), P75 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; 1 : 100), sortilin (Abcam, 1 : 500), JNK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1 : 100), cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175, Cell Signaling Technology, 1 : 1000), caspase 3, and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were employed. Antibody binding was detected by chemiluminescence with a Tanon 5500 Imaging System (Tanon Science & Technology Ltd., Shanghai, China) and quantified in the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Immunofluorescence Analysis

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature (RT) for 30 min and permeabilized or not permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), and nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at RT for 30 min. Coverslips were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-BDNF (Abcam, 1 : 500), rabbit anti-pro-BDNF (Alomone Labs, 1 : 400), anti-JNK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1 : 100), anti-phosphorylated-JNK (p-JNK) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1 : 100), rabbit anti-p75NTR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1 : 100), and goat anti-sortilin (Abcam, 1 : 500) antibodies. A secondary antibody conjugated with Cy3 or fluorescein isothiocyanate was incubated for 2 h at RT. Nuclei were stained for 5 min with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Cells were washed three times in PBST after each incubation. Pictures were taken using a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM 510).

2.7. Assays of Capillary-Like-Structure Formation and Cell Scratches In Vitro

We performed a cell scratch assay and capillary-like-structure formation experiments to evaluate the functional effects of pro-BDNF on MMECs in groups control, H/R, H/R + anti-pro-BDNF, and H/R + vehicle.

The assay of capillary-like-structure formation in vitro was performed as previously described [37]. Briefly, ECs (105/well) were cultured in a 24-well plate coated with 200 μL of Matrigel (356234; BD Biosciences). Capillary-like-structure formation was imaged after 12 h in five random microscopic visual fields by means of an inverted phase contrast microscope. The cell scratch assay was conducted to detect the migration of MMECs [38]. For the scratch assay, MMECs were cultured until confluence. After serum starvation for 24 h, a linear wound was administered by scratching the bottom of the dish with a pipette tip. The wound images were captured 24 h after scratching using a Motic AE31 Photometry and Dimensioning microscope (Milton, MA, USA).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All values are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA to compare multiple groups and by Student's t-test to compare two groups. Data with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed in the SPSS Statistics software (version 16.0).

3. Results

3.1. H/R Induces Apoptosis with Upregulation of Pro-BDNF in MMECs Exposed to High Concentration of Glucose

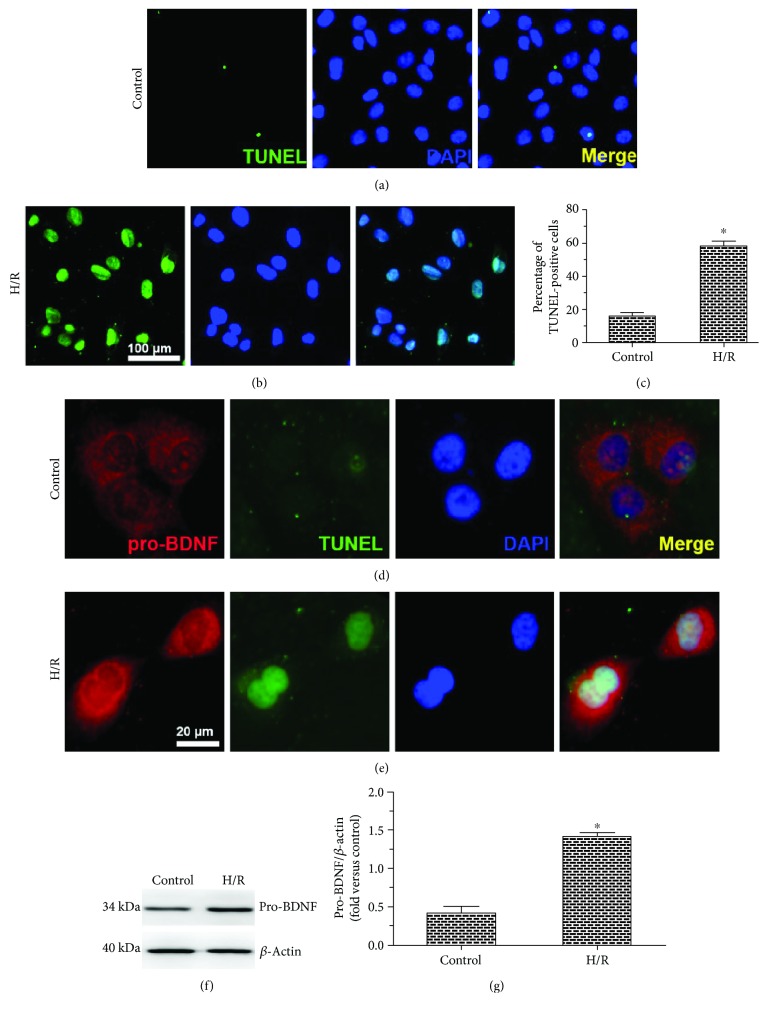

We first examined the effects of H/R on MMECs after exposure to high concentration of glucose (HG). Representative photographs were taken, and quantitative analysis of TUNEL positivity was performed to evaluate the proapoptotic effects. After exposure to HG, H/R caused a significant increase in the proportion of TUNEL-positive cells as compared to MMECs not subjected to H/R (control group), indicating that H/R induced MMEC apoptosis (Figures 1(a)–1(c)).

Figure 1.

Effects of H/R on the apoptosis and pro-BDNF expression among MMECs exposed to HG. (a, b) Representative images of the TUNEL assay of MMECs exposed to HG without (control) or with (H/R group) H/R. (c) The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells. H/R significantly increased the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells among MMECs, indicating the induction of apoptosis. (d, e) Immunostaining results on the pro-BDNF protein expression and a TUNEL assay. (f, g) Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis of pro-BDNF protein. H/R markedly increased the expression of pro-BDNF. The data were analyzed by the t-test. The error bars represent SEM. ∗P < 0.05 as compared with the control group.

Next, we examined the effect of H/R on pro-BDNF protein levels. The expression of pro-BDNF measured by immunostaining was observed in the cytoplasm and plasma membrane of MMECs. Of note, exposure to H/R caused overlapping signals of pro-BDNF staining and TUNEL staining among MMECs (Figures 1(d) and 1(e)), together with higher levels of pro-BDNF as measured by Western blot analysis in comparison with controls (Figures 1(f) and 1(g)). These results indicate that H/R exerted a proapoptotic effect and upregulated the pro-BDNF protein.

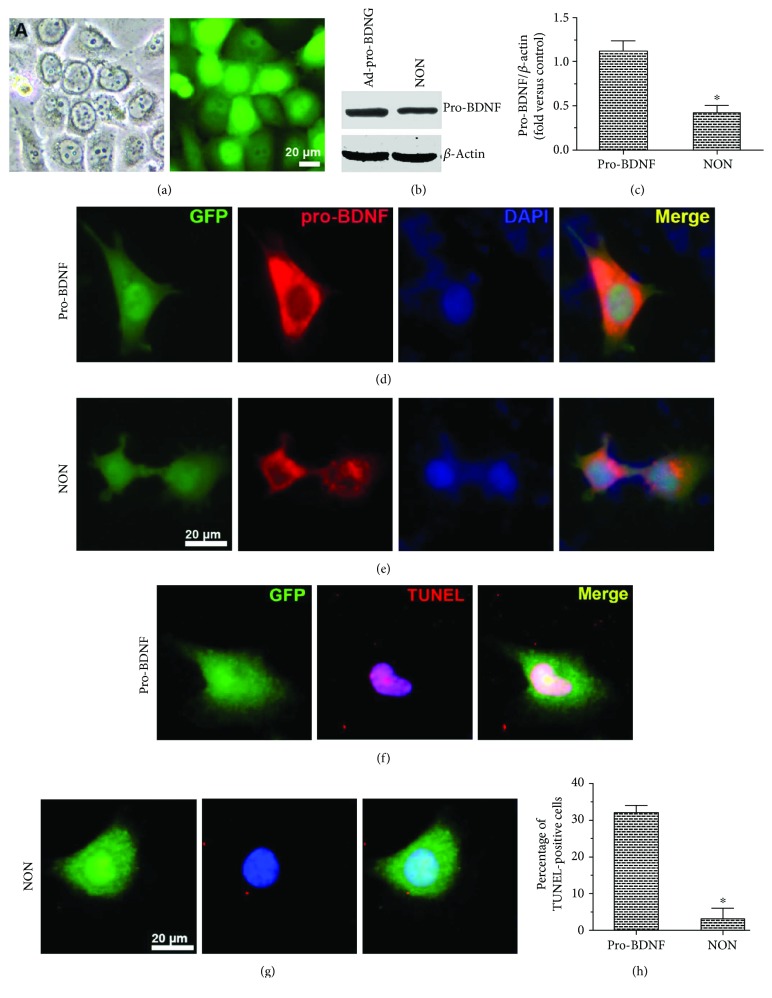

3.2. Pro-BDNF Overexpression Promotes MMEC Apoptosis

To test whether an increase in pro-BDNF levels exerted proapoptotic actions on MMECs under HG conditions, we transfected MMECs with either Ad-pro-BDNF or with Ad-GFP as a negative control group (NON). A TUNEL assay of adenovirus-infected MMECs under HG conditions was then performed (Figures 2(a)–2(e)). The protein expression of pro-BDNF significantly increased after transduction with Ad-pro-BDNF as determined by immunostaining and Western blot analysis, as compared with that in Ad-GFP-transfected cells (NON). In addition, Ad-pro-BDNF-transfected MMECs showed a significant increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells (Figures 2(f)–2(h)). In short, MMEC apoptosis was induced by pro-BDNF.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of pro-BDNF in MMECs and its effect on MMEC apoptosis. (a–e) MMECs were transfected with either pro-BDNF or Ad-GFP. Immunostaining, Western blotting, and quantitative analysis showed that the protein expression of pro-BDNF increased in MMECs after transduction with pro-BDNF. (f–h) Transfected cells were exposed to HG and then subjected to a TUNEL assay (f, g) and enumeration of TUNEL-positive cells (h) to evaluate apoptosis. Pro-BDNF overexpression markedly elevated the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells. The data were analyzed by the t-test. The error bars represent SEM. ∗P < 0.05 as compared with the control group or Ad-pro-BDNF group.

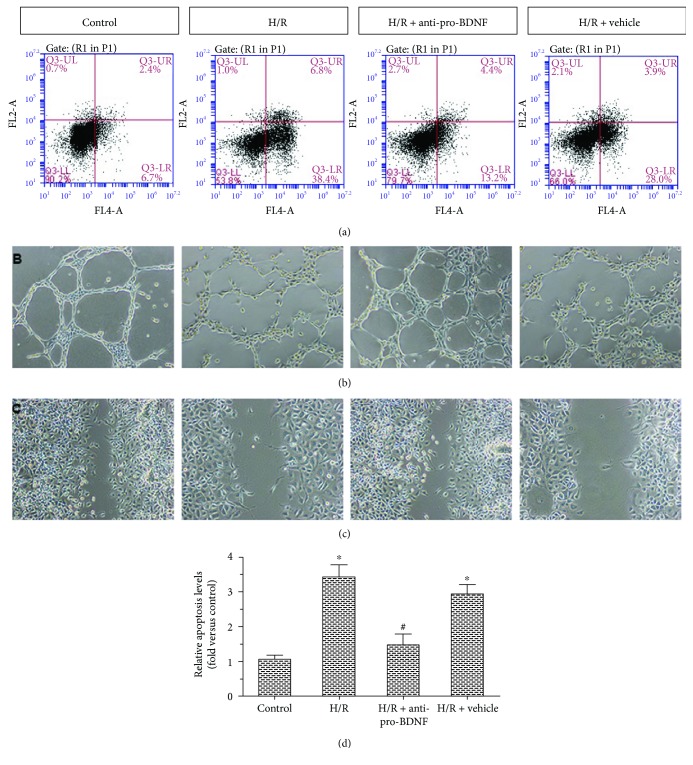

3.3. Pro-BDNF Is Required for H/R-Induced Apoptosis and Dysfunction

The proapoptotic action of H/R seemed to be mediated at least in part by upregulation of pro-BDNF. We next evaluated the relation between pro-BDNF and H/R-induced apoptosis (Figures 3(a) and 3(d)). Exposure of MMECs to H/R caused a significant increase in relative apoptosis levels. These effects were abrogated by the exogenous anti-pro-BDNF antibody. These results indicate that H/R could induce MMEC apoptosis by upregulating pro-BDNF.

Figure 3.

Effects of the anti-pro-BDNF antibody on apoptosis, migration, and capillary-like-structure formation among MMECs after exposure to HG and H/R. (a) Effects of pro-BDNF on apoptosis were analyzed by flow cytometry of MMECs after different treatments: control, H/R, H/R + anti-pro-BDNF, and H/R + vehicle. (b, c) The functional effects of pro-BDNF on MMECs were assessed by capillary-like-structure formation and cell scratch assays. (d) Relative apoptosis levels and fold changes are expressed in relation to the control group. The H/R group showed markedly increased relative apoptosis levels, decreased capillary-like-structure formation, and reduced cell migration when compared with the control group. These effects were reversed by treatment with the anti-pro-BDNF antibody to the levels similar to those in the control group. The data were subjected to one-way ANOVA. The error bars represent SEM. ∗P < 0.05 as compared with the control group; #P < 0.05 as compared with the H/R group or the H/R + vehicle group.

To address the functional effects of pro-BDNF on MMECs, capillary-like-structure formation experiments (Figure 3(b)) and a cell scratch assay (Figure 3(c)) were carried out. Exposure of MMECs to H/R decreased capillary-like-structure formation and EC migration; however, the exogenous anti-pro-BDNF antibody significantly enhanced H/R-induced migration of (and capillary-like-structure formation by) MMECs. Taken together, these data indicate that pro-BDNF was required for H/R effects in MMECs exposed to HG.

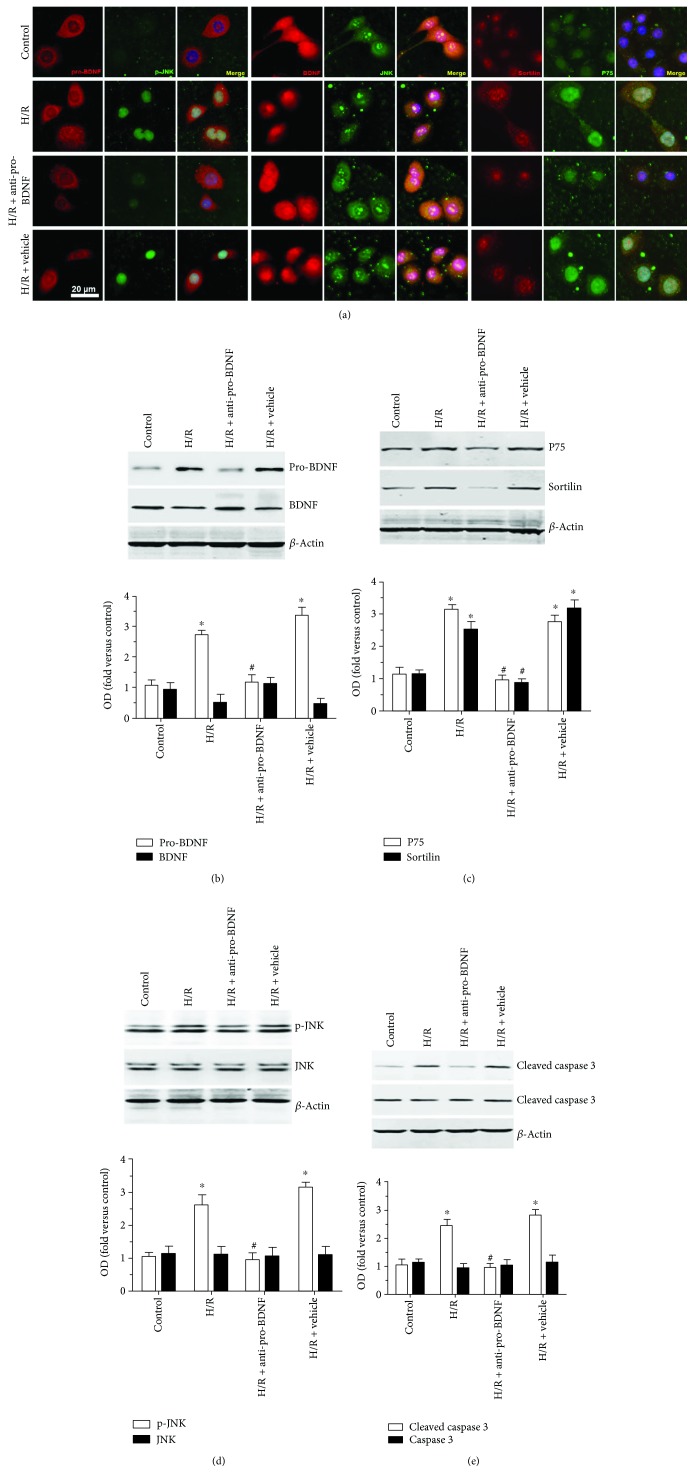

3.4. A Proapoptotic Protein Is Involved in the Regulation of Pro-BDNF Expression after H/R Injury in MMECs

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms behind the action of pro-BDNF under HG and H/R conditions, experiments were performed on several markers of apoptosis by immunostaining (Figure 4(a)) and Western blotting (Figures 4(b)–4(e)). Colocalization of p75NTR and sortilin in the cell membrane was observed in all groups. H/R led to increased p-JNK translocation to the nucleus. Exposure of MMECs to H/R caused significantly higher expression levels of pro-BDNF, p75NTR, sortilin, p-JNK, and cleaved caspase 3 as compared with MMECs maintained under normal conditions (P < 0.05). By contrast, there were no significant differences in BDNF, JNK, and caspase 3 expression levels after H/R. Of note, treatment with the anti-pro-BDNF antibody significantly reversed the increase in the protein expression of pro-BDNF, p75NTR, and sortilin and inhibited the activity of JNK and caspase 3 in MMECs after exposure to HG and H/R. Taken together, these data indicate that p75NTR and sortilin and activation of JNK and caspase 3 are associated with the H/R-induced cellular injury.

Figure 4.

Effects of the anti-pro-BDNF antibody on the expression of p75NTR and sortilin and apoptosis-related proteins. (a) Representative immunofluorescent images of pro-BDNF (red, first column), p-JNK (green, second column), BDNF (red, fourth column), JNK (green, fifth column), sortilin (red, seventh column), and p75NTR (green, eighth column) in groups control, H/R, H/R + anti-pro-BDNF, and H/R + vehicle. (b–e) Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis of pro-BDNF, BDNF (b), p75NTR, sortilin (c), JNK, p-JNK (d), caspase 3 and cleaved-caspase 3 expression (e) in response to different treatments. All the data were normalized to β-actin, and fold changes are expressed in relation to the control group. Exposure of MMECs to H/R resulted in significantly higher expression levels of pro-BDNF, p75NTR, and sortilin and in activation of JNK and caspase 3 as compared with MMECs maintained under normal conditions (control). Nonetheless, there were no significant differences in BDNF, JNK, and caspase 3 expression levels after H/R. Treatment with the anti-pro-BDNF antibody significantly reversed the increase in the protein expression of pro-BDNF, p75NTR, sortilin, p-JNK, and cleaved caspase 3 in MMECs after exposure to HG and H/R (H/R + anti-pro-BDNF). The data were subjected to one-way ANOVA. The error bars represent SEM. ∗P < 0.05 as compared with the control group; #P < 0.05 as compared with the H/R or H/R + vehicle group.

4. Discussion

Hyperglycemia, a common feature of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, is a key factor that contributes to the development of DM-related vascular disease and notably microvascular disease [39]. EC dysfunction and apoptosis have proved to play a vital role in the development of MIRI [40]. In the present study, no changes in cell migration and capillary-like-structure formation occurred, and no cell apoptosis was induced in MMECs cultured in DMEM high-glucose complete medium. However, in response to HG and H/R, MMECs showed increased levels of apoptosis and reduced migration and capillary-like-structure formation, suggesting that H/R resulted in MMEC injury. It is worth noting that pro-BDNF protein expression increased in the H/R-treated MMECs. Based on these results, we hypothesized that pro-BDNF might participate in the H/R-induced EC dysfunction and apoptosis.

One research group [41] reported that BDNF protects from cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Other researchers [17] found that BDNF protects human vascular ECs from apoptosis. In the present study, overexpression of pro-BDNF had proapoptotic effects on MMECs, but the neutralizing antibody to pro-BDNF significantly attenuated this apoptosis and the reduction in EC migration and capillary-like-structure formation by MMECs after exposure to HG and H/R. Consistent with the results obtained elsewhere [42–44], these data prove that pro-BDNF contributes to H/R-induced cell injury.

Pro-BDNF shows high-affinity binding to sortilin and performs its biological functions by acting on its receptors: p75NTR and sortilin [45]. Some studies have indicated that the JNK pathway contributes to the growth-inhibitory effect and apoptosis of ECs and that inhibition of JNK activation protects cardiomyocytes from I/R injury [46–49]. Pro-NGF/p75NTR/sortilin signaling increases JNK signaling [50]. Furthermore, cleavage-resistant pro-BDNF mutant (CR-pro-BDNF) treatment resulted in a rapid phosphorylation of JNK which are involved in p75NTR-induced apoptosis and an earlier appearance of active caspase 3 in cerebellar granule neurons [51]. Pro-BDNF has also been proved to be a proapoptotic ligand for sympathetic neurons and could induce neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin [24]. In the present study, the data on MMECs revealed that H/R, which enhanced pro-BDNF protein expression, induced P75NTR and sortilin protein expression and increased activation of JNK and caspase 3. In contrast, the anti-pro-BDNF antibody significantly reversed these effects. Collectively, our data suggest that pro-BDNF exerts a proapoptotic effect against myocardial I/R injury at least in part through the regulation of p75NTR-sortilin signaling and activation of JNK and caspase 3.

Diabetic nephropathy is a serious microvascular complication of DM; H/R promoted oxidative stress in NRK-52E cells exposed to HG accompanied by increased levels of Nrf2 and HO-1 protein expression [32, 46]. High glucose has also been proved to increase the permeability of cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Thus, the question of whether other molecular mechanisms contribute to the effect of pro-BDNF on H/R is an intriguing one and merits further investigation.

5. Conclusion

In summary, the major finding of our study is that inhibition of pro-BDNF may exhibit a beneficial effect against H/R by promoting MMEC migration and capillary-like-structure formation. Moreover, these effects are at least in part related to the decrease in MMEC apoptosis through p75NTR-sortilin-mediated activation of JNK and caspase 3. Our results may facilitate future studies on the therapeutic implications of pro-BDNF in the treatment of MIRI.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81370254). The authors are grateful to Man Li for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- BDNF:

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- MMECs:

Myocardial microvascular endothelial cells

- H/R:

Hypoxia/reoxygenation

- DM:

Diabetes mellitus

- CMECs:

Cardiac microvascular endothelial cells

- NGF:

Nerve growth factor

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor α

- JNK:

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MIRI:

Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Approval

All the experiments and procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Central South University, Changsha, Hunan 410011, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Fei Yu and Junmei Xu designed the study. Fei Yu and Yuezhu Liu conducted the experiments and collected the data. Fei Yu and Yuezhu Liu analyzed and interpreted the experimental data. Fei Yu and Junmei Xu prepared the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kengne A. P., Amoah A. G., Mbanya J. C. Cardiovascular complications of diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa. Circulation. 2005;112(23):3592–3601. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.544312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y., Li X., Peng D., et al. Usefulness of serum cathepsin L as an independent biomarker in patients with coronary heart disease. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2009;103(4):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedro-Botet J., Chillaron J. J., Benaiges D., Flores-Le Roux J. A. Cardiovascular prevention in diabetes mellitus: a multifactorial challenge. Clínica e Investigación en Arteriosclerosis. 2016;28(3):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.arteri.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan Y. C., Xia Z. K., Mu J. J., Zhang Q. C., Yin B. L. Increased connective tissue growth factor expression in a rat model of chronic heart allograft rejection. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2009;108(3):240–246. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Y. R., Zhao Y., Sun Y. W., et al. Detection of nanobacteria-like material from calcified cardiac valves with rheumatic heart disease. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2010;19(5):286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lejay A., Fang F., John R., et al. Ischemia reperfusion injury, ischemic conditioning and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2016;91:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pu D. R., Chiong J. R., Zhou Q. C. Clinical applications of N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide in heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases. Heart Failure Reviews. 2010;15(4):293–304. doi: 10.1007/s10741-009-9142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang M., Pu D.-R., Zhou Q.-C., Peng Q.-H., Tian L.-Q. Four-dimensional echocardiography with B-flow imaging and spatiotemporal image correlation in the assessment of congenital heart defects. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2010;30(5):443–448. doi: 10.1002/pd.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui H., Li X., Li N., et al. Induction of autophagy by Tongxinluo through the MEK/ERK pathway protects human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2014;64(2):180–190. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen K., Li G., Geng F., et al. Berberine reduces ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial apoptosis via activating AMPK and PI3K–Akt signaling in diabetic rats. Apoptosis. 2014;19(6):946–957. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-0977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding H. S., Yang J., Chen P., et al. The HMGB1–TLR4 axis contributes to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Gene. 2013;527(1):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y., Yang H., Song L., et al. AGGF1 protects from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating myocardial apoptosis and angiogenesis. Apoptosis. 2014;19(8):1254–1268. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang H. H., Chen Y., Gao C. Y., Cui Z. T., Yao J. M. Protective effects of microRNA-126 on human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury and inflammatory response by activating PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2017;42(2):506–518. doi: 10.1159/000477597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefer A. M., Tsao P. S., Lefer D. J., Ma X. L. Role of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of reperfusion injury after myocardial ischemia. The FASEB Journal. 1991;5(7):2029–2034. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.7.2010056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keefe K., Sheikh I., Smith G. Targeting neurotrophins to specific populations of neurons: NGF, BDNF, and NT-3 and their relevance for treatment of spinal cord injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms18030548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng L. R., Zhang Y. Y., Han J., et al. Nerve growth factor rescues diabetic mice heart after ischemia/reperfusion injury via up-regulation of the TRPV1 receptor. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2015;29(3):323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda K., Kermani P., Anastasia A., Obinata Y., Hempstead B. L., Kurihara H. BDNF protects human vascular endothelial cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2013;91(5):341–349. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2013-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunelli A., Dimauro I., Sgrò P., et al. Acute exercise modulates BDNF and pro-BDNF protein content in immune cells. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2012;44(10):1871–1880. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31825ab69b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monnier A., Garnier P., Quirie A., et al. Effect of short-term exercise training on brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Hypertension. 2017;35(2):279–290. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonchev A. B., Yamashima T., Guo J., Chaldakov G. N., Takakura N. Expression of angiogenic and neurotrophic factors in the progenitor cell niche of adult monkey subventricular zone. Neuroscience. 2007;144(4):1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick M. E., Rojas M., Moser-Katz T., Tzima E., Reader J. S. Natural aminoacyl tRNA synthetase fragment enhances cardiac function after myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2014;9(10, article e109325) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z. G., Li H., Huang Y., et al. Nerve growth factor-induced Akt/mTOR activation protects the ischemic heart via restoring autophagic flux and attenuating ubiquitinated protein accumulation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(3):5400–5413. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L., Yung K., Chan Y., Shum D., Bolam J. The proNGF-p75NTR-sortilin signalling complex as new target for the therapeutic treatment of Parkinsons disease. CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets. 2008;7(6):512–523. doi: 10.2174/187152708787122923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teng H. K., Teng K. K., Lee R., et al. ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(22):5455–5463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhanasekaran D. N., Reddy E. P. JNK signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27(48):6245–6251. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao J., Chen J., Xie L., Wang J., Feng C., Song J. Protective properties of sesamin against fluoride-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in kidney of carp (Cyprinus carpio) via JNK signaling pathway. Aquatic Toxicology. 2015;167:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning A. M., Davis R. J. Targeting JNK for therapeutic benefit: from junk to gold? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2003;2(7):554–565. doi: 10.1038/nrd1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen D. L., Engle J. T., Griffin E. A., et al. Imaging caspase-3 activation as a marker of apoptosis-targeted treatment response in cancer. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2015;17(3):384–393. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0802-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie L., Wu Y., Fan Z., Liu Y., Zeng J. Astragalus polysaccharide protects human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury: the role of PI3K/AKT, Bax/Bcl-2 and caspase-3. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2016;14(1):904–910. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong Z., Ye S., Xiong Y., et al. Decreased expression of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 induces liver injury via activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Transplant International. 2016;29(1):98–107. doi: 10.1111/tri.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X., Zhu W., Zhang P., et al. Apelin-13 stimulates angiogenesis by promoting cross‑talk between AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt signaling in myocardial microvascular endothelial cells. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2014;9(5):1590–1596. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Z. Y., Sun Q., Xia Z. Y., et al. Overexpression of DJ-1 reduces oxidative stress and attenuates hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in NRK-52E cells exposed to high glucose. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2016;38(3):729–736. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai Y. Y., Ruan C. S., Yang C. R., et al. ProBDNF signaling regulates depression-like behaviors in rodents under chronic stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(12):2882–2892. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo C., Zhong X. L., Zhou F. H., et al. Peripheral brain derived neurotrophic factor precursor regulates pain as an inflammatory mediator. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1, article 27171) doi: 10.1038/srep27171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiong J., Zhou L., Yang M., et al. ProBDNF and its receptors are upregulated in glioma and inhibit the growth of glioma cells in vitro. Neuro-Oncology. 2013;15(8):990–1007. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang C. R., Bai Y. Y., Ruan C. S., et al. Injection of anti-proBDNF in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) reverses chronic stress-induced adverse mood behaviors in mice. Neurotoxicity Research. 2017;31(2):298–308. doi: 10.1007/s12640-016-9687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang L., Yin M., Wei X., et al. Bach1 represses Wnt/β-catenin signaling and angiogenesis. Circulation Research. 2015;117(4):364–375. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grutzmacher C., Park S., Zhao Y., Morrison M. E., Sheibani N., Sorenson C. M. Aberrant production of extracellular matrix proteins and dysfunction in kidney endothelial cells with a short duration of diabetes. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2013;304(1):F19–F30. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00036.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aljofan M., Ding H. High glucose increases expression of cyclooxygenase-2, increases oxidative stress and decreases the generation of nitric oxide in mouse microvessel endothelial cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010;222(3):669–675. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bourke L. T., McDonnell T., McCormick J., et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies enhance rat neonatal cardiomyocyte apoptosis in an in vitro hypoxia/reoxygenation injury model via p38 MAPK. Cell Death & Disease. 2017;8(1, article e2549) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada S., Yokoyama M., Toko H., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects against cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction via a central nervous system–mediated pathway. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2012;32(8):1902–1909. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akil H., Perraud A., Melin C., Jauberteau M. O., Mathonnet M. Fine-tuning roles of endogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor, TrkB and sortilin in colorectal cancer cell survival. PLoS One. 2011;6(9, article e25097) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De la Cruz-Morcillo M. A., Berger J., Sanchez-Prieto R., et al. p75 neurotrophin receptor and pro-BDNF promote cell survival and migration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):34480–34497. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Z. Q., Sun Y., Li H. Y., Lim Y., Zhong J. H., Zhou X. F. Endogenous proBDNF is a negative regulator of migration of cerebellar granule cells in neonatal mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;33(8):1376–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deinhardt K., Chao M. V. Shaping neurons: long and short range effects of mature and proBDNF signalling upon neuronal structure. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li C., Zhang C., Wang T., Xuan J., Su C., Wang Y. Heme oxygenase 1 induction protects myocardiac cells against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis: the role of JNK/c-Jun/caspase-3 inhibition and Akt signaling enhancement. Herz. 2016;41(8):715–724. doi: 10.1007/s00059-016-4424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J. P., Zhang M. Y. Role for target of rapamycin (mTOR) signal pathway in regulating neuronal injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2017;41(1):145–153. doi: 10.1159/000455983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu X., Gu W., Lu H., et al. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end product ameliorates chronic intermittent hypoxia induced renal injury, inflammation, and apoptosis via P38/JNK signaling pathways. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2016;2016:13. doi: 10.1155/2016/1015390.1015390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J., Qin X., Cai X., et al. Mitochondrial JNK activation triggers autophagy and apoptosis and aggravates myocardial injury following ischemia/reperfusion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2015;1852(2):262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fortress A. M., Buhusi M., Helke K. L., Granholm A.-C. E. Cholinergic degeneration and alterations in the TrkA and p75NTR balance as a result of pro-NGF injection into aged rats. Journal of Aging Research. 2011;2011:10. doi: 10.4061/2011/460543.460543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koshimizu H., Hazama S., Hara T., Ogura A., Kojima M. Distinct signaling pathways of precursor BDNF and mature BDNF in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;473(3):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.