Abstract

Bacillus atrophaeus GQJK17 was isolated from the rhizosphere of Lycium barbarum L. in China, which was shown to be a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium as a new biological agent against pathogenic fungi and gram-positive bacteria. We present its biological characteristics and complete genome sequence, which contains a 4,325,818 bp circular chromosome with 4,181 coding DNA sequences and a G+C content of 43.3%. A genome analysis revealed a total of 8 candidate gene clusters for producing antimicrobial secondary metabolites, including surfactin, bacillaene, fengycin, and bacillibactin. Some other antimicrobial and plant growth-promoting genes were also discovered. Our results provide insights into the genetic and biological basis of B. atrophaeus strains as a biocontrol agent for application in agriculture.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the yield and quality of many medicinal plants, vegetables, fruits, and crops have decreased because of plant diseases caused by soil-borne pathogens [1–4]. Moreover, a large number of chemical pesticides and fertilizers have been used in agriculture that further caused quality reduction of agricultural products [5], pathogen resistance to chemicals [1], and environmental pollution [6]. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are a group of strains that localize in the plant rhizosphere and play an important role in preventing and controlling soil-borne diseases [7], promoting plant growth and development [8, 9], enhancing stress tolerance [10], and regulating and improving the rhizosphere soil environment [11–13]. Bacillus species are an important group of PGPR, and some of them have been widely used in agriculture as biocontrol agents [14–16].

Bacillus atrophaeus as a group of useful bacterium has been studied in many aspects. B. atrophaeus was verified to be a known biomolecule producer [17], which could produce bacteriocin [18], bioactive compounds [19], and biosurfactant proteins [20]. B. atrophaeus is also an important group of PGPR. B. atrophaeus M-35 was recognized as a PGPR member, and it was previously identified to effectively inhibit potato dry rot and rhizome rot of ginger caused by Fusarium species [21, 22]. B. atrophaeus also exhibits a strong inhibitory effect against poplar anthracnose caused by a predominant fungus, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [23]. B. atrophaeus CAB-1 was reported to display a high inhibitory activity against various fungal pathogens and was capable of suppressing cucumber powdery mildew and tomato gray mold [24]. Moreover, B. atrophaeus had an extraordinary activity in root colonization and crop protection [25], and it was verified to promote the growth of Zea mays L. and Solanum lycopersicum [26]. However, the biocontrol mechanisms of B. atrophaeus species as PGPR have not been well characterized to date.

The goji berries produced by Lycium barbarum L. have nutritional health and medicinal value [27, 28] because of the contained components, such as Lycium barbarum L. polysaccharides and betaine [29, 30]. They can enhance human immunity, regulate blood fat, lower blood pressure, inhibit the growth and mutation of cancer cells, resist radiation, and so on [31–33]. So, the cultivated land for Lycium barbarum L. has been increased year by year, especially in China. With the continuous expansion of planting areas for Lycium barbarum L. and the continuous planting activity year by year, a variety of fungal soil-borne diseases are arising and seriously affecting the yield and quality of Lycium barbarum L. Root rot is one of the most important diseases of Lycium barbarum L. and Fusarium spp. (e.g., F. solani) are the main pathogens [34].

Strain GQJK17 was isolated from the rhizosphere of Lycium barbarum L. in Ningxia, China, and identified to be a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium aimed at the root rot of Lycium barbarum L. It was identified to be B. atrophaeus and has the most significant inhibition effect on the root rot pathogen F. solani among all the selected strains. To further study the genetic basis and molecular mechanism of its biocontrol ability, we performed the complete genome sequencing and annotation. The secondary metabolic gene clusters for pathogen resistance and some plant growth-promoting genes are discovered.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Isolation and Property Analysis

Strain GQJK17 was isolated from rhizosphere soil samples of Lycium barbarum L. collected from Ningxia, China. All physiological and biochemical tests were performed at 37°C. The colony morphology was determined after 24 h incubation on LB agar medium. Cellular morphology and spore detection were performed by spore staining using 5% malachite green dye and 0.5% fuchsin dye [43] and examined by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan). Some physiological and biochemical characteristics of GQJK17 were determined as follows. Oxidase activity was determined using 1% solution of tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine [44]. Catalase activity was determined by assessing the production of bubbles after the addition of a drop of 3% H2O2 [45]. Nitrate reduction, methyl red test (M-R), Voges-Prokauer reaction (V-P), indole production, and carbon utilization were tested using the bacteria microbiochemical identification tube (HOPEBIO, China) [45].

2.2. The Phylogenetic Analysis

The genomic DNA of strain GQJK17 was extracted using the genomic DNA kit (TIANGEN, China). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as follows: 5 min at 95°C (predegeneration); 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C (denaturation), 1 min at 56°C (annealing), and 1 min at 72°C (extension); followed by 10 min at 72°C (final extension). The 16S rDNA sequence was obtained using primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) and then analyzed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed with some species of the genus Bacillus based on the 16S rDNA sequences by MEGA 6.0.

2.3. The Determination of Antagonistic Properties

The antagonistic experiments were performed as reported [46]. The antifungal activity of strain GQJK17 was tested against Fusarium solani. F. solani with a diameter of 6 mm was inoculated in the center of a PDA agar plate and cultured at 28°C for one day. Then, strain GQJK17 was inoculated in one side of F. solani at a distance of 2 cm and incubated for another 3 to 5 days. After incubation, the inhibition zone was observed. The antibacterial assays of GQJK17 were performed against Escherichia coli DH5α and Bacillus subtilis 168. The precultured strain DH5α or 168 was incubated in 5 mL of LB liquid medium at 37°C for 10 h. Then, 1 mL of the culture was mixed with 100 mL of LB semisolid medium (with 1% agar) and poured into a sterile Petri dish. Strain GQJK17 was inoculated on the center of a cooled medium and incubated at 28°C for 24 h.

2.4. Medium Optimization

The culture medium of strain GQJK17 was optimized using bean sprouts as the basic medium. The plate counting method was used to estimate the strain growth. The suitable carbon sources (sucrose, glucose, lactose, corn flour, and soluble starch), nitrogen sources (including the organic nitrogen sources: beef extract, peptone, yeast powder, and soybean meal, and the inorganic nitrogen source: (NH4)2SO4, NH4NO3, NH4Cl, and Urea), and inorganic salts (MgSO4, CaCO3, K2HPO4, and KH2PO4) were determined by single factor experiments. The orthogonal test (designed by orthogonal design assistant II V3.1) [47] was used to predict the optimum medium for strain GQJK17.

2.5. Genome Sequencing and Annotation

The complete genome of strain GQJK17 was sequenced by the Illumina HiSeq and PacBio platforms. The SMRT Analysis 2.3.0 [48] (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/SMRT-Analysis/wiki/SMRT-Pipe-Reference-Guide-v2.3.0) was used to assemble the whole genome sequence. The NCBI Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline (PGAAP) was used to perform the gene annotation. The gene functions were further analyzed by BLASTP using five databases (Cluster of Orthologous Groups of proteins: COG, Gene Ontology: GO, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes: KEGG, Non-Redundant Protein Database: NR, and Swiss-Prot). The carbohydrate-active enzyme analyses of the genome also utilized the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CAZy) v.20161020 [49] (http://www.cazy.org/). RepeatMasker (3-3-0, http://www.repeatmasker.org/) was used to predict interspersed repeated sequences, and TRF (4.04, http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html) was used to search tandem repeats. tRNAscan-SE 1.3.1, rRNAmmer 1.2, and Rfam were used to determine tRNA, rRNA, and sRNA, respectively. The potential secondary metabolic gene clusters were predicted using antiSMASH v.4.0.2 [50]. IslandViewer 4 (http://www.pathogenomics.sfu.ca/islandviewer2/query.php) was used to predict genomic islands (GIs) [51]. The complete and circular genome map was created by Circos v.0.64 [52] (http://www.circos.ca/), including noncoding RNAs and gene function annotations.

3. Results

3.1. The Isolation and Identification of Strain GQJK17

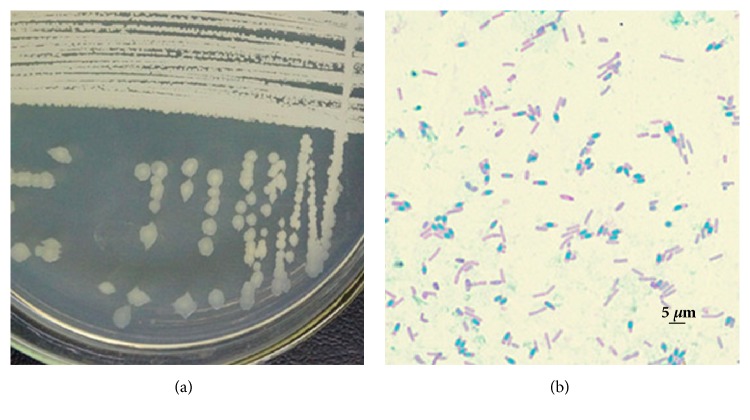

Strain GQJK17 was isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Lycium barbarum L. in Ningxia, China, and cultivated on LB medium at 37°C. The colony morphology of strain GQJK17 is nearly circular, smooth, moist, and milky white after being cultured on LB agar medium for 24 h. The cellular morphology of strain GQJK17 is rod-shaped and strain GQJK17 can produce spores. Its colony and cellular morphology are shown in Figures 1(a) and 1(b). Some physiological and biochemical traits of strain GQJK17 were tested. The properties of oxidase activity, starch hydrolysis, M-R, and indole production are negative, but the catalase activity, citrate utilization, nitrate reduction, and V-P are positive. The carbon utilization experiments showed that strain GQJK17 could utilize mannitol, Arabic candy, sorbitol, and maltose, but not xylose, cellobiose, and lactose (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Morphological characteristics of GQJK17. Colony morphology (24 h) (a) and cellular morphology and spore (magnification 10 × 100) (b). GQJK17 was inoculated on LB agar medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Spores were stained with 5% malachite green dye and 0.5% magenta dye.

Table 1.

Characteristics of physiology and biochemistry of GQJK17.

| Properties | GQJK17 | Properties | GQJK17 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidase | - | Mannitol utilization | + |

| Catalase | + | Xylose utilization | - |

| Citrate utilization | + | Cellobiose utilization | - |

| Starch hydrolysis | + | Arabic candy utilization | + |

| Nitrate reduction | + | Sorbitol utilization | + |

| methyl red (M-R) | - | Maltose utilization | + |

| Voges-Prokauer (V-P) | + | Lactose utilization | - |

| Indole production | - |

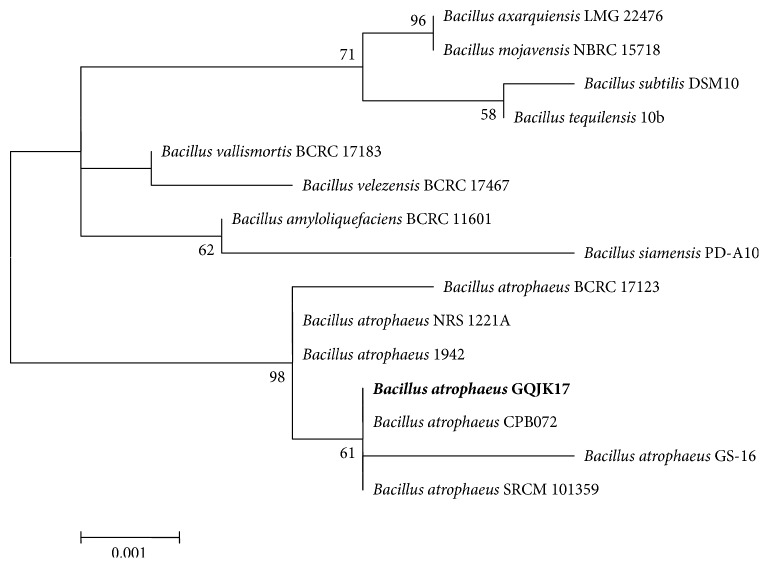

The phylogenetic analysis of strain GQJK17 based on 16S rDNA sequences was conducted by MEGA 6.0 with related Bacillus species (Figure 2) to show the phylogenetic relationships. Strain GQJK17 was successfully clustered to B. atrophaeus. Up to now, only four complete genome sequences of this species have been obtained except GQJK17, including strains SRCM101359, 1942, NRS 1221A, and BA59. The closest relative of strain GQJK17 is B. atrophaeus SRCM 101359.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 and members of the genus Bacillus based on 16S rDNA gene sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGA 6.0 program and evolutionary distances were computed by the Maximum Likelihood method. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages of 1000 replications) >50% are indicated at the branch points. The scale bar indicates 0.001 nucleotide substitutions per site.

3.2. The Biocontrol Efficacy of Strain GQJK17

The antagonistic activities of strain GQJK17 against F. solani, B. subtilis 168, and E. coli DH5α were tested. In Figure 3, it is shown that strain GQJK17 exhibits antagonistic activity against F. solani and B. subtilis but no effect on E. coli indicating potential applications for controlling some pathogenic fungi and gram-positive bacteria. Among all the isolated Bacillus strains, GQJK17 has the most significant inhibitory effect on the root rot pathogen F. solani of Lycium barbarum L. GQJK17 can adapt to the saline-alkali environment in the isolated area Ningxia. As a PGPR, strain GQJK17 could also produce siderophores and show casein degradation activity (data not show). Thus, GQJK17 was a potential strain to improve plant growth as a biocontrol agent or microbial fertilizer.

Figure 3.

In vitro antagonistic activities of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 against F. solani (a), B. subtilis (b), and E. coli (c). The antifungal activity of GQJK17 was tested against F. solani. Newly cultivated hyphal plugs of F. solani were placed on the center of a PDA plate and incubated for 1 day at 28°C. Then, strain GQJK17 was inoculated onto one side of the plug at a distance of 2 cm and incubated for another 3 days. The antibacterial assays of GQJK17 were performed against E. coli and B. subtilis. The precultured E. coli or B. subtilis was incubated in 5 mL of LB liquid medium for 10 h at 37°C. Then, 1 mL of the culture was mixed with 100 mL of LB semisolid medium. Strain GQJK17 was inoculated on the center of the plate and incubated for 1 day at 28°C.

3.3. The Medium Optimization of Strain GQJK17

To adapt the actual application of strain GQJK17, we also optimized the culture medium of strain GQJK17. The bean sprouts were used as the basic medium, which could provide the necessary nutrients for strain GQJK17 growth and reduce production costs. By single factor experiments, the optimal sources of carbon, organic nitrogen, inorganic nitrogen, and inorganic salt of strain GQJK17 were determined to be glucose, soybean meal, NH4NO3, and MgSO4, respectively. The orthogonal experiments were designed (Supplementary S1) and the optimal medium contained 3% glucose, 1.5% soybean meal, 0.3% NH4NO3, and 0.3% MgSO4. The colony numbers of strain GQJK17 were significantly increased from 3.21 × 108 cfu/mL to 7.98 × 109 cfu/mL using the optimized medium.

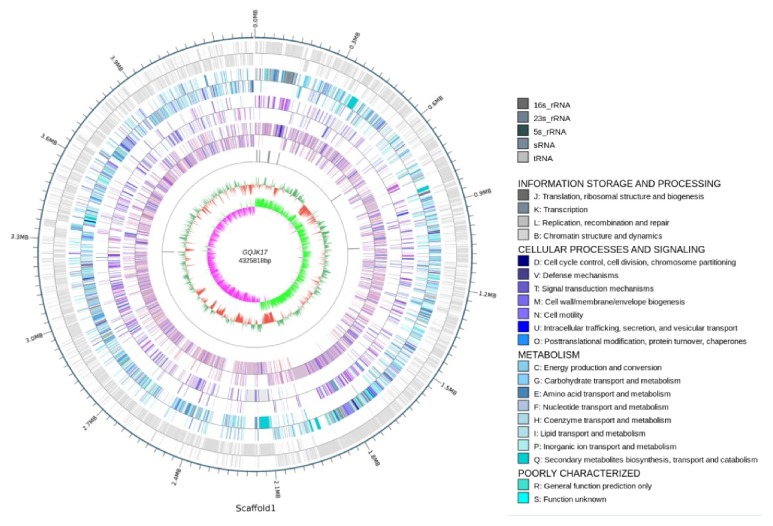

3.4. Genome Sequence and Genome Features of Strain GQJK17

A total of 1,364 Mb clean raw data were generated and the coverage of the genome was 307.9×. From the 126,058 subreads, approximately 1,289,931,176 bp were obtained. The genome of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 contains a 4,325,818 bp circular chromosome with a G+C content of 43.3%, including 4,015 protein-coding genes, 84 tRNA, 24 rRNA, and 5 ncRNA (Table 2 and Figure 4). No plasmid was found. The whole genome sequence of strain GQJK17 has been deposited in GenBank under the accession number CP022653. There were 3,373 genes that were assigned to the COG databases, accounting for 84.01% among the protein-coding genes (Table 3). Most genes have been annotated; however, 22.53% of the protein-coding genes are poorly characterized and are assigned to the R and S groups. The genes encoding amino acid transport and metabolism, transcription, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, and inorganic ion transport and metabolism account for a large proportion (each more than 6%). Furthermore, the analysis of CAZy showed that 154 genes were related to carbohydrate enzymes. This indicates the better absorption capacity and response ability of this species for amino acids, carbohydrates, and irons in the living environment.

Table 2.

The general genome feature of B. atrophaeus GQJK17.

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,325,818 |

| G+C content (%) | 43.3 |

| Total number of genes | 4,294 |

| Total size of protein-coding genes (bp) | 3,829,380 |

| Protein-coding genes | 4015 |

| Average CDS size (bp) | 916 |

| rRNA number | 24 |

| tRNA number | 84 |

| ncRNA number | 5 |

| Pseudo genes (total) | 166 |

Figure 4.

Circular genome map of B. atrophaeus GQJK17. From the outside to the center, circle 1: the size of complete genome; circles 2 to 4: the predicted protein-coding genes by using COG, KEGG, and GO databases, respectively, different colors represent different function classifications; circle 5: ncRNA; circle 6: G+C content, with >43.26% G+C in green, with ≤43.26% G+C in red; the inner circle: G+C skew, with G% >C% in peak green, with G% <C% in purple.

Table 3.

COG categories of B. atrophaeus GQJK17.

| COG code | Description | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | Chromatin structure and dynamics | 1 | 0.03% |

| C | Energy production and conversion | 179 | 5.31% |

| D | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning | 35 | 1.04% |

| E | Amino acid transport and metabolism | 340 | 10.08% |

| F | Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 78 | 2.31% |

| G | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 260 | 7.71% |

| H | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 126 | 3.74% |

| I | Lipid transport and metabolism | 112 | 3.32% |

| J | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | 162 | 4.80% |

| K | Transcription | 289 | 8.57% |

| L | Replication, recombination and repair | 120 | 3.56% |

| M | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | 186 | 5.51% |

| N | Cell motility | 60 | 1.78% |

| O | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | 101 | 2.99% |

| P | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 217 | 6.43% |

| Q | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | 92 | 2.73% |

| R | General function prediction only | 454 | 13.46% |

| S | Function unknown | 308 | 9.13% |

| T | Signal transduction mechanisms | 146 | 4.33% |

| U | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | 45 | 1.33% |

| V | Defense mechanisms | 62 | 1.84% |

3.5. Genetic Basis for Producing Antimicrobial and Plant Growth-Promoting Metabolites

Strain GQJK17 was selected due to its inhibition effects on pathogenic fungi and gram-positive bacteria (Figure 3), which indicated the existence of antimicrobial gene clusters. In the genome of strain GQJK17, a total of 13 secondary metabolic gene clusters were predicted using antiSMASH (v.4.0.2) (Table 4), among them eight gene clusters belonging to nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) or polyketide synthetases (PKS). These clusters were mainly responsible for biological resistance. The potentially antifungal secondary metabolites were surfactin, fengycin, pelgipeptin, xenocoumacin, bacillomycin, and rhizocticin. Surfactin and pelgipeptin also have antibacterial abilities. There were also gene clusters for antibacterial effects only and the predicted metabolites were bacillaene and anthracimycin. Compared with the other four complete genome sequences of this species, SRCM101359, 1942, NRS 1221A, and BA59, the main gene clusters predicted by antiSMASH (v.4.0.2) for producing antimicrobial secondary metabolites were generally similar. They all contained the biosynthetic gene clusters for surfactin, bacillaene, fengycin, rhizocticin, and bacillomycin. However, the biosynthetic genes of xenocoumacin were only discovered in strains GQJK17 and SRCM101359. In addition, the biosynthetic genes coding for pelgipeptin and anthracimycin only appeared in strain GQJK17. Our findings highlight the evolutionary conservation of molecular genetic mechanism of B. atrophaeus strains for biocontrol ability and the specialization of strain GQJK17.

Table 4.

The potential gene clusters encoding the secondary metabolites in B. atrophaeus GQJK17.

| Number | Cluster Categorya | Metaboliteb | Position | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nrps | Surfactin | BaGK_01865- BaGK_02085 |

Antifungal, Antibacterial |

[15] |

| 2 | Bacteriocin-Nrps- Transatpks-Otherks |

Bacillaene | BaGK_09425- BaGK_09810 |

Antibacterial | [35] |

| 3 | Transatpks-Nrps | Fengycin | BaGK_10375- BaGK_10710 |

Antifungal | [15] |

| 4 | Ladderane- Cf_fatty_acid -Nrps |

Pelgipeptin | BaGK_12700- BaGK_12950 |

Antibacterial, antifungal |

[36] |

| 5 | Transatpks | Anthracimycin | BaGK_11000- BaGK_11250 |

Antibacterial | [37] |

| 6 | Nrps-T1pks | Xenocoumacin | BaGK_03970- BaGK_04195 |

Antifungal | [38] |

| 7 | Cf_putative | Bacillomycin | BaGK_20300- BaGK_20325 |

Antifungal | [39, 40] |

| 8 | Sactipeptide- Head_to_tail-Nrps |

Rhizocticin | BaGK_01040- BaGK_01305 |

Antifungal | [41] |

| 9 | Nrps | Bacillibactin | BaGK_16720- BaGK_16940 |

Siderophore | [42] |

| 10 | Terpene | Unknown | BaGK_06190 -BaGK_0629 5 |

||

| 11 | Terpene | Unknown | BaGK_10750 -BaGK_1084 5 |

||

| 12 | T3pks | Unknown | BaGK_11290 -BaGK_1152 5 |

||

| 13 | Thiopeptide | Unknown | BaGK_17030 -BaGK_1716 5 |

aCluster categories were analyzed by antiSMASH (v.4.0.2).

bThe secondary metabolites were predicted according to the gene clusters.

There were four other secondary metabolic gene clusters in strain GQJK17 and the functions of those are still unclear. Interestingly, two gene clusters potentially producing terpenes were identified. Terpenes are a large class of organic compounds produced by some plants, bacteria, and fungi, which may be used as additives in food and cosmetics industries or exhibit antimicrobial or anticarcinogenic properties [53]. Some other antimicrobial-related genes could also be discovered in strain GQJK17, such as the synthetic genes of glucanase, ribonuclease, and proteases.

Moreover, the genome of strain GQJK17 contains many plant growth-promoting genes. One secondary metabolic gene cluster was predicted to produce bacillibactin, which is a kind of strong siderophore that can increase the absorption of ferric ions in soil for plant growth [54]. In addition to the synthetic gene cluster of bacillibactin, strain GQJK17 also harbors other plant growth-promoting genes codifying the production of useful substances, including butanone, phytase, and phosphatase. Other genes are likely involved in cell motility, molecular communication, and environmental responses.

3.6. Genomic Islands Analysis

The whole genome sequence of GQJK17 was analyzed by IslandViewer 4, and 14 GIs were discovered (Supplementary S2). Genomic Islands (GIs) are part of the genome sequences presenting the horizontal gene transfer from other species. The GIs in the genome of strain GQJK17 express a variety of proteins mainly involved in glycoside hydrolase, phage proteins, fimbrial proteins, transporters, and regulatory factors. Five phage protein genes are found in GIs, which indicate the previous infection by phages. A polyketide synthase, two glycoside hydrolases were identified, which are related to the antimicrobial activities of GQJK17. Some transcriptional regulators (e.g., LysR family regulator) can regulate the expression genes involved in metabolism, virulence, quorum sensing, and motility [55], and they might be related to the antagonistic properties. Type IV secretion protein Rhs can regulate cell-to-cell contact-dependent competition [56]. Certain Rhs were also reported to have antibacterial activity.

4. Discussion

Lycium barbarum L. is a significant and commercial crop because of its nutritional and medicinal value [27]. In recent years, due to long-term cultivation and continuous cropping, Lycium barbarum L. was increasingly affected by soil-borne diseases in China. Especially, the spread of root rot seriously affected the yield and quality of Lycium barbarum L. In this study, we screened out a strain GQJK17 from the rhizosphere of Lycium barbarum L. Biocontrol experiments showed that strain GQJK17 could inhibit the pathogen F. solani of Lycium barbarum L. root rot and also repress the growth of B. subtilis 168. Morphological observation and phylogenetic analysis showed that GQJK17 was closely related to B. atrophaeus CPB072. B. atrophaeus species is a PGPR which has considerable effects on inhibiting some soil-borne diseases and promoting the growth of some plants [22]. The biocontrol characteristics of strain GQJK17 revealed its important roles as a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium. This strain provides an excellent resource for developing new microbial fertilizers and shows interesting prospects for agricultural applications.

To further study the genetic basis and molecular mechanism of strain GQJK17 as PGPR, we sequenced its complete genome that presented the genetic basis of its biocontrol function and a molecular background for subsequent transformation. Eight secondary metabolic gene clusters were found out, which might be responsible for its function as a new biocontrol agent. Some other plant growth-promoting genes for producing many useful substances were also found in strain GQJK17. Comparing the genome sequence of strain GQJK17 with the other three complete genome sequences of this species, the main gene clusters for producing antimicrobial secondary metabolites were generally similar. Our findings further highlight the evolutionary conservation of B. atrophaeus species for biocontrol ability as PGPR.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2017YFD0200804), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grants nos. 31700094, 31770115, and 31600090), the Science and Technology Major Projects of Shandong Province (no. 2015ZDXX0502B02), and the funds of Shandong “Double Tops” Program (no. SYL2017XTTD03).

Contributor Information

Binghai Du, Email: du_binghai@163.com.

Yanqin Ding, Email: dyq@sdau.edu.cn.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary S1: the orthogonal test design of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 to optimize the medium.

Supplementary S2: the genomic islands information of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 that analyzed by IslandViewer 4.

References

- 1.Wang L.-Y., Xie Y.-S., Cui Y.-Y., et al. Conjunctively screening of biocontrol agents (BCAs) against fusarium root rot and fusarium head blight caused by Fusarium graminearum. Microbiological Research. 2015;177:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Y., Sangare L., Wang Y., et al. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus subtilis SG6 antagonistic against Fusarium graminearum. Journal of Biotechnology. 2015;194:10–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Donnell K., Ward T. J., Geiser D. M., Kistler H. C., Aoki T. Genealogical concordance between the mating type locus and seven other nuclear genes supports formal recognition of nine phylogenetically distinct species within the Fusarium graminearum clade. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2004;41(6):600–623. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J., Hsiang T., Bhadauria V., Chen X.-L., Li G. Plant Fungal Pathogenesis. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/9724283.9724283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windels C. E. Economic and social impacts of Fusarium head blight: Changing farms and rural communities in the Northern Great Plains. Journal of Phytopathology. 2000;90(1):17–21. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilman D., Cassman K. G., Matson P. A., Naylor R., Polasky S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature. 2002;418(6898):671–677. doi: 10.1038/nature01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu K., Newman M., McInroy J. A., Hu C.-H., Kloepper J. W. Selection and assessment of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for biological control of multiple plant diseases. Journal of Phytopathology. 2017;107(8):928–936. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-17-0051-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo H., Yang Y., Liu K., et al. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Delftia tsuruhatensis MTQ3 and the Identification of Functional NRPS Genes for Siderophore Production. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3687619.3687619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahmoune B., Morsli A., Khelifi-Slaoui M., et al. Isolation and characterization of three new PGPR and their effects on the growth of Arabidopsis and Datura plants. Journal of Plant Interactions. 2017;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2016.1269215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habib S. H., Kausar H., Saud H. M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance salinity stress tolerance in okra through ROS-scavenging enzymes. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016:10. doi: 10.1155/2016/6284547.6284547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivasakthi S., Usharani G., Saranraj P. Biocontrol potentiality of plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPR)-Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus subtilis: A review. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2014;9(16):1265–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy P. P. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) Springer India. 2012;18(3):131–158. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharyya P. N., Jha D. K. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): emergence in agriculture. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2012;28(4):1327–1350. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y. G., Kang H. K., Kwon K.-D., Seo C. H., Lee H. B., Park Y. Antagonistic Activities of Novel Peptides from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens PT14 against Fusarium solani and Fusarium oxysporum. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2015;63(48):10380–10387. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ongena M., Jacques P. Bacillus lipopeptides: versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends in Microbiology. 2008;16(3):115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govindasamy V., Senthilkumar M., Magheshwaran V., et al. Plant Growth and Health Promoting Bacteria. Vol. 18. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011. Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp.: Potential PGPR for Sustainable Agriculture; pp. 333–364. (Microbiology Monographs). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sella S. R. B. R., Vandenberghe L. P. S., Soccol C. R. Bacillus atrophaeus: Main characteristics and biotechnological applications – A review. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 2015;35(4):533–545. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2014.922915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein T., Düsterhus S., Stroh A., Entian K.-D. Subtilosin Production by Two Bacillus subtilis Subspecies and Variance of the sbo-alb Cluster. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(4):2349–2353. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2349-2353.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu F., Sun W., Su F., Zhou K., Li Z. Draft genome sequence of the sponge-associated strain Bacillus atrophaeus C89, a potential producer of marine drugs. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012;194(16):4454–4454. doi: 10.1128/JB.00835-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das Neves L. C. M., De Oliveira K. S., Kobayashi M. J., Penna T. C. V., Converti A. Biosurfactant production by cultivation of Bacillus atrophaeus ATCC 9372 in semidefined glucose/casein-based media. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2007;137-140(1-12):539–554. doi: 10.1007/s12010-007-9078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Recep K., Fikrettin S., Erkol D., Cafer E. Biological control of the potato dry rot caused by Fusarium species using PGPR strains. Biological Control. 2009;50(2):194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanmugam V., Thakur H., Gupta S. Use of chitinolytic Bacillus atrophaeus strain S2BC-2 antagonistic to Fusarium spp. for control of rhizome rot of ginger. Annals of Microbiology. 2013;63(3):989–996. doi: 10.1007/s13213-012-0552-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang H., Wu Z., Tian C., Liang Y., You C., Chen L. Identification and characterization of the endophytic bacterium Bacillus atrophaeus XW2, antagonistic towards Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Annals of Microbiology. 2015;65(3):1361–1371. doi: 10.1007/s13213-014-0974-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X., Li B., Wang Y., et al. Lipopeptides, a novel protein, and volatile compounds contribute to the antifungal activity of the biocontrol agent Bacillus atrophaeus CAB-1. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;97(21):9525–9534. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan W. Y., Dietel K., Lapa S. V., Avdeeva L. V., Borriss R., Reva O. N. Draft genome sequence of Bacillus atrophaeus UCMB-5137, a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium. Genome Announcements. 2013;1(3) doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00233-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang X.-F., Zhou D., Guo J., Manter D. K., Reardon K. F., Vivanco J. M. Bacillus spp: From rainforest soil promote plant growth under limited nitrogen conditions. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2015;118(3):672–684. doi: 10.1111/jam.12720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amagase H., Farnsworth N. R. A review of botanical characteristics, phytochemistry, clinical relevance in efficacy and safety of Lycium barbarum fruit (Goji) Food Research International. 2011;44(7):1702–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie J.-H., Tang W., Jin M.-L., Li J.-E., Xie M.-Y. Recent advances in bioactive polysaccharides from Lycium barbarum L., Zizyphus jujuba Mill, Plantago spp., and Morus spp.: Structures and functionalities. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;60:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C. C., Chang S. C., Inbaraj B. S., Chen B. H. Isolation of carotenoids, flavonoids and polysaccharides from Lycium barbarum L. and evaluation of antioxidant activity. Food Chemistry. 2010;120(1):184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin M., Huang Q., Zhao K., Shang P. Biological activities and potential health benefit effects of polysaccharides isolated from Lycium barbarum L. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2013;54(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Q., Lv X., Wu T., et al. Composition of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides and their apoptosis-inducing effect on human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells. Food and Nutrition Research. 2015;59 doi: 10.3402/fnr.v59.28696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X. M., Ma Y. L., Liu X. J. Effect of the Lycium barbarum polysaccharides on age-related oxidative stress in aged mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;111(3):504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bo R., Zheng S., Xing J., et al. The immunological activity of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides liposome in vitro and adjuvanticity against PCV2 in vivo. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016;85:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Z., Wang G. Occurrence and control of wolfberry root rot. Journal of Plant Protection. 1994;21(3):249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X.-H., Vater J., Piel J., et al. Structural and functional characterization of three polyketide synthase gene clusters in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB 42. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188(11):4024–4036. doi: 10.1128/JB.00052-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian C.-D., Liu T.-Z., Zhou S.-L., et al. Identification and functional analysis of gene cluster involvement in biosynthesis of the cyclic lipopeptide antibiotic pelgipeptin produced by Paenibacillus elgii. BMC Microbiology. 2012;12, article no. 197 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang K. H., Nam S.-J., Locke J. B., et al. Anthracimycin, a potent anthrax antibiotic from a marine-derived actinomycete. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013;52(30):7822–7824. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X., Qiu D., Yang H., Liu Z., Zeng H., Yuan J. Antifungal activity of xenocoumacin 1 from Xenorhabdus nematophilus var. pekingensis against Phytophthora infestans. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;27(3):523–528. doi: 10.1007/s11274-010-0485-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moyne A.-L., Shelby R., Cleveland T. E., Tuzun S. Bacillomycin D: An iturin with antifungal activity against Aspergillus flavus. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2001;90(4):622–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eshita S. M., Roberto N. H. Bacillomycin Lc, a New Antibiotic of the Iturin Group: Isolations, Structures, and Antifungal Activities of the Congeners. The Journal of Antibiotics. 1995;48(11):1240–1247. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kugler M., Loeffler W., Rapp C., Kern A., Jung G. Rhizocticin A, an antifungal phosphono-oligopeptide of Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633: biological properties. Archives of Microbiology. 1990;153(3):276–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00249082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X. H., Koumoutsi A., Scholz R., et al. Comparative analysis of the complete genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25(9):1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/nbt1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheng-Mei Y. E., Gao W. Improvement of bacteria's spore staining. Journal of Microbiology. 2011;31(1):106–109. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovacs N. Identification of Pseudomonas pyocyanea by the oxidase reaction. Nature. 1956;178(4535):p. 703. doi: 10.1038/178703a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li W.-J., Xu P., Schumann P., et al. Georgenia ruanii sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from forest soil in Yunnan (China), and emended description of the genus Georgenia. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2007;57(7):1424–1428. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chernin L., Ismailov Z., Haran S., Chet I. Chitinolytic enterobacter agglomerans antagonistic to fungal plant pathogens. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1995;61(5):1720–1726. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1720-1726.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shu Q., Ding J. C., Bao Q. X., Li M. P., Yan H. Orthogonal test design for optimization of the extraction of flavonid from the Fructus Gardeniae. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences. 2011;24(6):688–696. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chin C.-S., Alexander D. H., Marks P., et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2013;10(6):563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cantarel B. I., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(1):D233–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medema M. H., Blin K., Cimermancic P., et al. AntiSMASH: Rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(2):W339–W344. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bertelli C., Laird M. R., Williams K. P., et al. IslandViewer 4: Expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(1):W30–W35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., et al. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Research. 2009;19(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao J., Bao X., Li C., Shen Y., Hou J. Improving monoterpene geraniol production through geranyl diphosphate synthesis regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2016;100(10):4561–4571. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus velezensis LM2303, a biocontrol strain isolated from the dung of wild yak inhabited Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Journal of Biotechnology. 2017;251:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maddocks S. E., Oyston P. C. F. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology. 2008;154(12):3609–3623. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fritsch M. J., Trunk K., Diniz J. A., Guo M., Trost M., Coulthurst S. J. Proteomic identification of novel secreted antibacterial toxins of the Serratia marcescens Type VI secretion system. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2013;12(10):2735–2749. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.030502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary S1: the orthogonal test design of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 to optimize the medium.

Supplementary S2: the genomic islands information of B. atrophaeus GQJK17 that analyzed by IslandViewer 4.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.