Abstract

Mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC) diseases and congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) share extensive clinical overlap but are considered to have distinct cellular pathophysiology. Here, we demonstrate that an essential physiologic connection exists between cellular N-linked deglycosylation capacity and mitochondrial function. Following identification of altered muscle and liver mitochondrial amount and function in two children with a CDG subtype caused by NGLY1 deficiency, we evaluated mitochondrial physiology in NGLY1 disease human fibroblasts, and in NGLY1-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts and C. elegans. Across these distinct evolutionary models of cytosolic NGLY1 deficiency, a consistent disruption of mitochondrial physiology was present involving modestly reduced mitochondrial content with more pronounced impairment of mitochondrial membrane potential, increased mitochondrial matrix oxidant burden, and reduced cellular respiratory capacity. Lentiviral rescue restored NGLY1 expression and mitochondrial physiology in human and mouse fibroblasts, confirming that NGLY1 directly influences mitochondrial function. Overall, cellular deglycosylation capacity is shown to be a significant factor in mitochondrial RC disease pathogenesis across divergent evolutionary species.

Keywords: Mitochondria, N-glycanase, Glycosylation, C. Elegans, Fibroblasts

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC) diseases and congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) represent two of the most common biochemical categories of inherited metabolic disease, each with extensive clinical and genetic heterogeneity yet sharing overlapping manifestations and multi-system involvement (Freeze et al., 2015; Gorman et al., 2016). Their basic pathophysiology has been considered distinct at the cellular level since they primarily localize to different organelles: RC diseases involve disordered energy metabolism in mitochondria while CDGs have impaired cellular glycosylation capacity in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and/or Golgi complex. Surprisingly, our recently reported transcriptome meta-analysis in diverse causes of human RC disease identified one of the most dysregulated genes to be NGLY1 (Zhang and Falk, 2014) that encodes N-glycanase, which is the major cytosolic N-deglycosylase enzyme that functions in glycoprotein disposal by removing N-glycans from asparagine (Asn) residues of misfolded glycoproteins (Suzuki et al., 2016). While N-glycanase has known functions in the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) or folding (ERAF) pathways with links to the autophagic and lysosomal proteolytic pathways (Huang et al., 2015; Suzuki, 2016; Suzuki et al., 2016), it has not previously been linked to mitochondrial function. Thus, the unexpected RC disease transcriptome meta-analysis finding of upregulated NGLY1 expression suggested a previously unrecognized connection may exist between the pathophysiology of primary RC disease and CDG, where cellular N-deglycosylation capacity is an important factor in RC disease adaptation or pathogenesis.

Here, we report novel data to further support that an essential physiologic connection exists between cellular N-deglycosylation capacity and mitochondrial function. Specifically, we identified tissue-specific mitochondrial abnormalities in two patients with autosomal recessive NGLY1 loss-of-function mutations, a recently identified CDG subtype (Caglayan et al., 2015; Enns et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2017) with loss of cellular N-glycanase activity (He et al., 2015; Suzuki, 2015). To explore the underlying mechanism for this observation, we evaluated mitochondrial function in genetic models of NGLY1 deficiency across distinct evolutionary species, including C. elegans NGLY1 (png-1)-knockout worms, mouse embryonic fibroblasts from Ngly1-knockout mice (Suzuki et al., 2003), and human fibroblasts from the subjects in whom in vivo tissue analyses demonstrated mitochondrial abnormalities. We demonstrate that NGLY1 deficiency significantly reduced mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity, with increased mitochondrial oxidant stress in all three models. Lentiviral-based NGLY1 cDNA rescue in both Ngly1-knockout MEFs and NGLY1-deficient human fibroblasts restored NGLY1 expression and mitochondrial physiology. Overall, these data suggest that NGLY1expression is necessary to maintain normal mitochondrial function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. PCR characterization of png-1 deletion in C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans strains N2 Bristol (wild-type) and RB1452 (png-1−/−) were obtained from obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The deletion in png-1 (having 69.7% similarity by protein length to human NGLY1 orthologue) was confirmed in the png-1−/− worm strain (RB1452) by PCR using the following primer sets: ok1654-F: 3’-CTCGCCGAGACCTTTCAGTT-5’ and ok1645-R: 3’-ACTAGGCCACGCACTCAATA-5’. The thermocycling protocol for all PCR reactions was 5 min at 95 °C, then 30 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C → 30 s at 60 °C → 1 min at 72 °C, and finally 5 min at 72 °C. For gel analysis of PCR products, 5 μL of each PCR reaction was run on a 1% agarose Gel (Invitrogen/Life Technologies), according to the vendor recommendations. Wild-type nematodes yielded an amplification product of 1.7 kb, whereas, the knockout strain produced a 0.8 kb product (Fig. S1).

2.2. Png-1 knockout worm lifespan analyses

Animals were maintained at 20 °C throughout experiments. Synchronized C. elegans cultures were initiated by bleaching young adults to obtain eggs. Collected eggs were allowed to hatch overnight on 10 cm Nematode Growth Media (NGM) plates without E. coli, after which L1-arrested larvae were transferred to 10 cm NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli. Lifespan analysis was performed as previously reported (McCormack et al., 2015), with 100 μg/mL (400 uM) FUDR. Mortality was confirmed by stimulating nematodes lightly with a platinum wire; if the nematode did not move after stimulations it was scored as dead and removed from the plate. Worms that died of protruding/bursting vulva, bagging, or crawling off the agar were censored. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad prism 5.0.

2.3. In vivo mitochondrial physiology analyses using fluorescence quantitation in png-1 knockout worms

Mitochondrial matrix oxidant burden (MitoSOX Red), mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE), and mitochondrial content (MitoTracker Green FM, MTG) analyses were performed using terminal pharyngeal bulb fluorescence relative quantitation, as described previously (Dingley et al., 2010), with minor modifications. Specifically, synchronous populations of first day young adults were moved to 35 mm NGM plates spread with OP50 E. coli and either 10 μm MitoSOX Red (matrix oxidant burden), 100 nm TMRE (mitochondrial membrane potential), or 10 μm MitoTracker Green FM (mitochondrial content) for 24 h. After 24 h, 50 worms per condition were transferred onto 35 mm NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli for 1 h, to allow clearing of residual dye from the gut. Worms were then paralyzed in situ with 4 mg/mL levamisole. Photographs were taken in a darkened room at × 160 magnification with a Cool Snap cf2 camera (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). A CY3 fluorescence cube set (MZFLIII, Leica, Bannockburn, IL, USA) was used for MitoSOX and TMRE fluorescence. A GFP2 filter set (Leica) was used for MitoTracker Green FM fluorescence. Exposure times were 2 s, 320 msec and 300 msec, respectively, for MitoSOX, TMRE and MitoTracker Green FM. The resulting images were background subtracted, and the nematode terminal pharyngeal bulb was manually circled to obtain mean intensity of the region by using ImageJ software (Hartig, 2013). Fluorescence data for the png-1−/− strain was normalized to its same day wild-type control to account for day-to-day variation. A minimum of three independent experiments of approximately 50 animals per replicate were studied per strain per dye. The significance of the difference in the mean fluorescence intensity between strains under different experimental conditions was assessed by mixed-effect ANOVA, which takes into account potential batch effect due to samples being experimentally prepared, processed, and analyzed on different days by including a batch random effect in the model. A statistical significance threshold was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3.

2.4. Mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell culture

Ngly1-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF-PK, NGLY1−/−) and wild-type control mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF-WT) were kindly provided by Dr. Tadashi Suzuki (RIKEN Global Research Cluster, Japan) (Huang et al., 2015). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) containing 4.5 g/L glucose and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (CellGro), and 2 mM l-glutamine without antibiotics at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2.

2.5. Human fibroblast cell culture

Human Fibroblasts cell lines (FCLs) were obtained when available and/or established in the Clinical CytoGenomics Laboratory from skin biopsies performed in the Mitochondrial Medicine Center at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (M.J.F., CHOP IRB#08–6177). Deidentified research cell lines were studied in accordance with the terms of the written informed consent. Briefly, FCLs were cultured in a mixture of DMEM (Gibco) containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 1 g/L glucose and supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (CellGro), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μg/mL uridine (Calbiochem) since mitochondrial disease deficient lines become uridine auxotrophs, with 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

2.6. Generation of lentiviruses and retroviruses

pLenti-GIII-CMV-NGLY1-GFP-2A-Puro construct or the control empty parental plasmid were obtained from ABM (Applied Biological Materials Inc., Canada). Lentivirus was packaged in 293 T HEK cells grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) and supplemented with 10% FBS. 293 T cells cultured in 10 cm dishes were transfected with a solution consisting of lentiviral DNA, and ViraPower™ Lentiviral Packaging Mix included pLP1, pLP2, and pLP/VSVG (ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY), and Opti-MEM using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 48 h after transfection, supernatants were filtered with a 0.45 μm pore size. Lentiviral particles were then used for polybrene-mediated transduction using standard protocols. MEF cells were selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin, FCL-M1 cells with 0.5 μg/mL puromycin and FCL-M2 cells with 1 μg/mL puromycin for 7 days. A ddVenus fluorescent pLNCX2 retroviral construct was kindly provided by Dr. Peter Cresswell (Yale University, Newhaven, CT). Plasmid DNA was transfected into a Plat-E packaging cell line (Cell Biolabs Inc., San Diego, CA) with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Virus-containing supernatants were harvested 48–72 h after transfection. MEF cells were infected and selected with 300 μg/mL neomycin (Invitrogen) for 7 days.

2.7. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo kit (Promega, Madison). Briefly, cells were plated in 96-well plates and treated with rotenone or ethanol (Control). 72 h post-treatment, CellTiter-Glo reagent was added and luminescence was measured as per the manufacturer’s instructions using SYNERGY HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT).

2.8. NGLY1 mutation analysis by semiquantitative RT-PCR

For the identification of NGLY1 mutation sites, total RNA was isolated from cells via an RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands), with RNA concentration determined by spectrophotometry and RNA quality assessed by conventional agarose gel electrophoresis. cDNA was prepared from total RNA with random hexamers using a Superscript III RT kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As reported in a recent paper describing the distribution of NGLY1 mutations (Lam et al., 2017), three primer pairs were designed to cover the common mutation sites of NGLY1 exons. Semi-quantitative PCR was performed to amplify cDNA fragments using the primers detailed in Table 2. Amplification reactions were performed using a P×2 thermal cycler (Techne, Staffordshire, U.K.) and consisted of the following steps: 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 10 min. The amount of cDNA was normalized to the intensity of the PCR products of the housekeeping gene (GAPDH). PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel, and band intensities corresponding to NGLY1 were quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Table 2.

NGLY1 primer sequences used for human cell cDNA analysis.

| Primer set | Start | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| NGLY1 11F | 429 | GTGGGTTAAACCAGCACACAAG |

| NGLY1 11R | 1118 | AGCTTCTTGCCCCATCCTAT |

| NGLY1 12F | 961 | CGAGCTGTAGGGTTTGAAGC |

| NGLY1 12R | 1626 | TCGGGCCAAATATACCATGT |

| NGLY1 13F | 1385 | CAGTGGCTTGGAGAGTAGCC |

| NGLY1 13R | 1817 | GGGCCAAATATACCATGTGC |

2.9. NGLY1 gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from FCLs, reverse transcribed, and qRT-PCR was performed on cDNA for relative gene expression studies, as previously described (Peng et al., 2015). Taqman Gene Expression Assays used in human cells were NGLY1 (Hs01046153_ml, Applied Biosystems) and NGLY1 (Hs00217653_ml, Applied Biosystems) as target genes and ACTB (Hs01060665_gl, Applied Biosystems) as endogenous gene. Quantitative analysis of changes in the expression level starting with 40 ng cDNA per well, with triplicate analyses per replicate experiment, was performed by qPCR reaction on a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR machine from Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). At least three biological replicates were performed per condition. Sequence Detection Software v2.0.6 was used for relative quantitative analysis of gene expression.

2.10. NGLY1 western immunoblot analysis

Cells were harvested for immunoblot analysis by washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysing in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40) supplemented with protease inhibitors (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.5 mM PMSF. After incubation on ice for 20 min, samples were spun at 13,000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min and supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined using DC protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Protein extract samples were diluted in reducing Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) (Bio-Rad) with β-mercaptoethanol at 95 °C for 4 min and run on 4–15% Tris-Glycine gradient gels (Bio-Rad). Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), which were then blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer for 1 h and incubated with the primary antibodies (anti-NGLY1 antibody, 1:500, Sigma-Aldrich), β-actin (1:2000, Cell Signaling) overnight and then Odyssey IRDye goat anti-rabbit or rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibodies at 1:10,000 for 30 min. Membranes were scanned directly using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified with Image J software (Hartig, 2013).

2.11. NGLY1 activity cellular assay

ddVenus (deglycosylation-dependent Venus) fluorescence analysis was performed to analyze NGLY1 activity in MEF-WT and MEF-PK cells, as previously described (He et al., 2015). ddVenus fluorescence only occurs when a protein has reached the endoplasmic reticulum, undergone N-glycosylation, retrotranslocated, and been deglycosylated in the cytosol. MG132 treatment is used to prevent the protein from undergoing proteasomal degradation. For wild-type and NGLY1−/− fibroblasts that were stably infected with pLNCX2 retrovirus-mediated ddVenus, 2 × 105 cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate and cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 overnight. Cells were then treated with 2.5 μM MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). On the following day, cells were imaged by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry.

2.12. Cellular mitochondrial physiology quantification by fluorescence assisted cell sorting (FACS) analysis

Cells were collected in cell growth medium after trypsin treatment, centrifuged, and resuspended in HBSS to obtain 1–5 × 105 cells per sample, as previously reported (Dingley et al., 2012; Gai et al., 2013). Samples were loaded with either 50 nM MitoTrackerGreen (MTG) or MitoTracker Deep Red (MTR) at 37 °C for 15 min, 20 μM Tetra-MethylRhodamine Ethyl ester (TMRE) at 37 °C for 10 min, or 5 μM MitoSOX at 37 °C for 10 min. Cells then were washed twice with 1×PBS, and resuspended in 400 μL PBS. Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with a 488 nm laser with 530/30 nm emission for MTG, 581/644 nm for MTR, 585/42 nm emission for TMRE, 647/52 nm emission for MitoSox. A total of 10,000 events were recorded per condition. Background subtracted geometric means of MitoSOX or TMRE were calculated as percent change relative to same day controls. Duplicate technical measurements were performed and control cell samples without fluorescence dye exposure were run in parallel.

2.13. Mitochondrial high-resolution respiratory capacity quantitation in intact cells by Oxygraph-2 K (Oroboros) analysis

Oxygen consumption rates were measured polarographically using high-resolution respirometry (Oxygraph-2k, Oroboros Instruments, Austria). For determination of respiratory activity in intact cells, cells were cultured in tissue culture flasks until reaching over 90% confluence, at which time they were harvested with trypsin. Cells were resuspended in fresh culture DMEM medium containing 11 mM glucose and 2 mM glutamine, and evaluated by high-resolution respirometry using the Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros Instruments, Austria). As previously described, two cell lines were simultaneously analyzed in two separate chambers in 2 mL volume containing 0.5–1 × 106 cells per chamber. Respiration was measured in intact cells at 37 °C in 2 mL culture medium (DMEM) and inhibitors for the different mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes were added into each chamber. Routine consumption, oligomycin-independent respiration (proton leak), FCCP-stimulated respiration (ETS capacity-maximum respiration) and ROX (residual oxygen consumption in the presence of rotenone and anti-mycin A) were measured in intact cells, as described previously (Peng et al., 2015). After observing steady-state respiratory flux, the ATP synthase (complex V) inhibitor oligomycin(1 μg/mL, Sigma) was added, followed by uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation by stepwise titration of FCCP (in 1.5 uMol increments, Sigma) to assess complex I and complex Il-uncoupled respiration. Finally, respiration was inhibited by the complex I and complex III inhibitors rotenone ( 0.5 μM, Sigma) and antimycin A (2.5 μM, Sigma), respectively. All values were corrected for ROX. DatLab software (Oroboros Instruments) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using ANOVA and paired t-tests to compare group means.

3. Results

3.1. NGLY1 disease patients have altered in vivo mitochondrial physiology

In vivo mtDNA content and/or mitochondrial mass quantitation was abnormal in two NGLY1 disease unrelated subjects who underwent clinical evaluations in the CHOP Mitochondrial Medicine Center. Both subjects were enrolled in CHOP IRB study #08-6177 (PI, MJF). Specifically, an NGLY1 disease female subject (corresponding to subject “FCL-M1” in Table 1) at age 2 years in whom we identified compound heterozygous mutations p.402_403del (c.1205_1207del) and p.R524X (C.1570C > T) presented with global developmental delay, movement disorder, microcephaly, thin corpus callosum on brain MRI at one year old, reduced tear production, transaminase elevation, failure to thrive, sensorineural hearing loss, and intermittent mild lactic acidemia. She had abnormal liver mitochondrial morphology with depleted cristae and significant mitochondrial DNA depletion (39% of control mean), with normal electron transport chain enzyme activities in frozen liver tissue. Mitochondrial abnormalities were also present on liver and skeletal muscle biopsies in a 5 year old male NGLY1 disease subject with compound heterozygous mutations p.W535X (C.1604G > A) and p.L637X (c.1910delT) who presented with global developmental delay with normal brain MRI/MRS, intractable epilepsy, movement disorder, stridor with vocal cord paresis necessitating tracheotomy, failure to thrive, and transaminase elevation. His liver biopsy revealed abnormal cristae and mitochondrial proliferation, while his quadriceps muscle biopsy revealed dramatic mitochondrial proliferation (5-fold increased citrate synthase relative to control mean) and mitochondrial DNA proliferation (472% of mean value of age- and tissue-matched controls), and increase of all electron transport chain enzyme activities. Skin biopsy for fibroblast cell line establishment was refused by the family. Overall, these cases demonstrate significant disruption of in vivo mitochondrial physiology in muscle and liver from two unrelated NGLY1 disease subjects.

Table 1.

NGLY1 mutation description in human fibroblast cell lines (FCL).

| # | Fibroblast cell line ID | NGLY1 genotype |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | FCL-C1 | Healthy subject control line 1 |

| 2 | FCL-C2 | Healthy subject control line 2 |

| 3 | FCL-M1 | c.1205_1207del; c.1570C > T |

| 4 | FCL-M2 | c.1201A > T; c.1201A > T |

| 5 | FCL-M3 | c.931G > A; c.730 T > C |

| 6 | FCL-M4 | c.622C > T; c.930C > T |

3.2. NGLY1 deficiency reduced viability in C. elegans and human fibroblasts

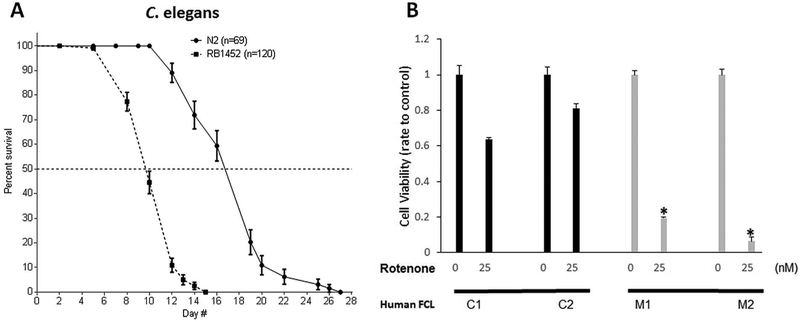

As NGLY1-CDG causes global developmental and growth delays in affected individuals (Lam et al., 2017), we postulated that C. elegans mutant worms with NGLY1 deletion would exhibit an analogous finding of reduced lifespan. Lifespan analysis was performed in the NGLY1 deficient worms, RB1452, in which the ok-1654 (png-1) allele has a 1.1 kilobase deletion that causes an in-frame deletion of residues 67–180 (Supp Fig. S1). RB1452 worms were significantly short-lived, with 53% decreased median lifespan compared to wild type (WT) N2 Bristol worms grown at 20 °C (median lifespan 10 versus 19 days, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A and Supp Fig. S2). Therefore, NGLY1 deficiency substantially alters physiology sufficient to impair C. elegans survival. We further assessed whether NGLY1 deficiency alters survival of human NGLY1 disease fibroblasts (Subjects M2, M3, and M4 were reported in Lam et al., 2017). Cell viability was determined in NGLY1 deficient human fibroblasts and normal control cell lines grown in either glucose media, or glucose-free plus galactose media, and then exposed for 72 h to different concentrations of rotenone, a mitochondrial RC complex I inhibitor (Fig. 1B). When grown in DMEM media containing 10% FBS, no glucose, and 10 mM galactose, 5% of NGLY1-deficient fibroblasts FCL-M1 and 18% of FCL-M2 survived after 72 h exposure to 25 nM rotenone, compared to survival under these conditions in 66% of healthy control 1 and 74% of healthy control 2 fibroblasts (p < 0.001, n = 3). Therefore, NGLY1 disease human fibroblasts showed increased sensitivity to mitochondrial inhibition than in controls under conditions that forced cellular reliance on mitochondrial oxidation phosphorylation (OXPHOS, as galactose is a substrate for energy production in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) only through OXPHOS and not via glycolysis). These results were suggestive that mitochondrial RC inhibition requires intact NGLY1 expression for cell survival.

Fig. 1. NGLY1 deficiency reduces C. elegans lifespan and human fibroblast survival with RC inhibition.

(A) Lifespan plot of RB1452 (png-1−/−) relative to N2 Bristol (wild-type) C. elegans strains at 20 °C. Animal number studied per strain is indicated in legend. Median lifespan was significantly reduced by 53% in RB1452 relative to N2 Bristol (p < 0.0001). Results of biological replicate lifespan analysis are shown in File S2. (B)NGLY1 disease patient fibroblasts (FCL-M1 and FCL-M2) displayed reduced cell viability relative to that of two healthy subject control human fibroblast lines (FCL-C1 and FCL-C2) after 72 h exposure to 25 nM rotenone. 1000 cells were studied per well in triplicate per condition, with 3 biological replicate experiments performed. *, p < 0.05.

3.3. Ngly1-expression was decreased in NGLY1 disease human fibroblasts and Ngly1-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)

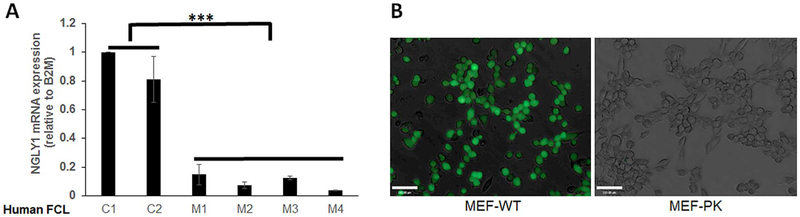

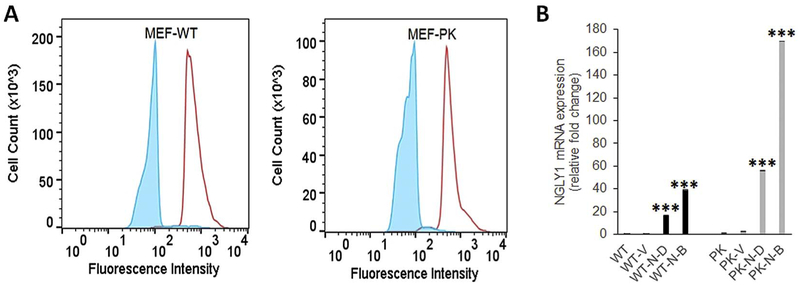

NGLY1 mRNA expression was compared relative to the endogenous control β2-microglobin (B2M) in 6 human fibroblast cell lines, which included two normal controls and 4 different NGLY1 human disease subjects (Table 1). Robust NGLY1 expression was seen in both human control cells, with significantly decreased or near-absent NGLY1 expression in all four NGLY1 disease human fibroblast lines (Fig. 2A). Fibroblast line FCL-M2 (NGLY1 human disease subject 2) harboring the homozygous nonsense mutation R401X was severely affected, with > 96% reduction in NGLY1 expression (p < 0.001). Western immunoblot analysis of NGLY1 expression in these fibroblast cell lines, as well as in the NGLY1-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell line, MEF-PK, confirmed a similar magnitude reduction in NGLY1 protein expression (Supp Fig. S3). In contrast, NGLY1 expression appeared increased in two different mitochondrial RC disease fibroblast lines (Supp Fig. S3), as is consistent with prior transcriptome analysis suggesting increased NGLY1 expression occurs in primary mitochondrial RC disease (Zhang and Falk, 2014). Assessment of NGLY1 enzymatic activity was performed using the ddVenus reporter system in NGLY1-knockout MEFs. MEF-PK (NGLY1−/−) and MEF-WT cells were infected with a retrovirus encoding the engineered NGLY1 substrate ddVenus (Grotzke et al., 2013), and stable cell lines were selected by neomycin. The ddVenus construct contains an N-glycosylation site (N-F-T) which confers fluorescence on the protein only when it is first glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum and subsequently deglycosylated by NGLY1, whose enzymatic reaction converts the Asn to Asp. MG-132, as a cell-permeable proteasome inhibitor, is used to prevent degradation of the fluorescent protein. ddVenus expressing MEF-WT cells, treated with MG-132, showed very bright fluorescence, reflecting robust N-glycanase 1 enzymatic activity. However, ddVenus-expressing MEF-PK cells treated with MG-132 had complete absence of ddVenus fluorescence, demonstrating that NGLY1-knockout MEFs had abolished N-glycanase 1 enzymatic activity (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrated that NGLY1 deficiency not only abolished NGLY1 transcript and NGLY1 protein expression in four unrelated human NGLY1 disease fibroblast lines, but also diminished N-glycanase de-glycosylation activity in NGLY1-knockout MEFs.

Fig. 2. NGLY1 expression and activity are reduced in human fibroblasts and MEF cells with NGLY1 mutations.

(A)NGLY1 relative gene expression was tested by qRT-PCR analysis in 2 healthy subject and 4 NGLY1 disease subject human fibroblast lines, with β32M used as endogenous control. ***, p < 0.001, n = 3 biological replicate experiments performed. (B) NGLY1 activity in MEF cells was evaluated with the ddVenus (deglycosylation-dependent Venus) Fluorescent substrate. NGLY1 enzyme activity was readily detected in wild-type (WT) MEF cells that microscopically displayed GFP signal, but no GFP signal was present in NGLY1-knockout (PK) fibroblasts. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

3.4. NGLY1 deficiency impaired mitochondrial physiology in C. elegans, NGLY1−/− MEFs, and NGLY1-deficient human fibroblasts

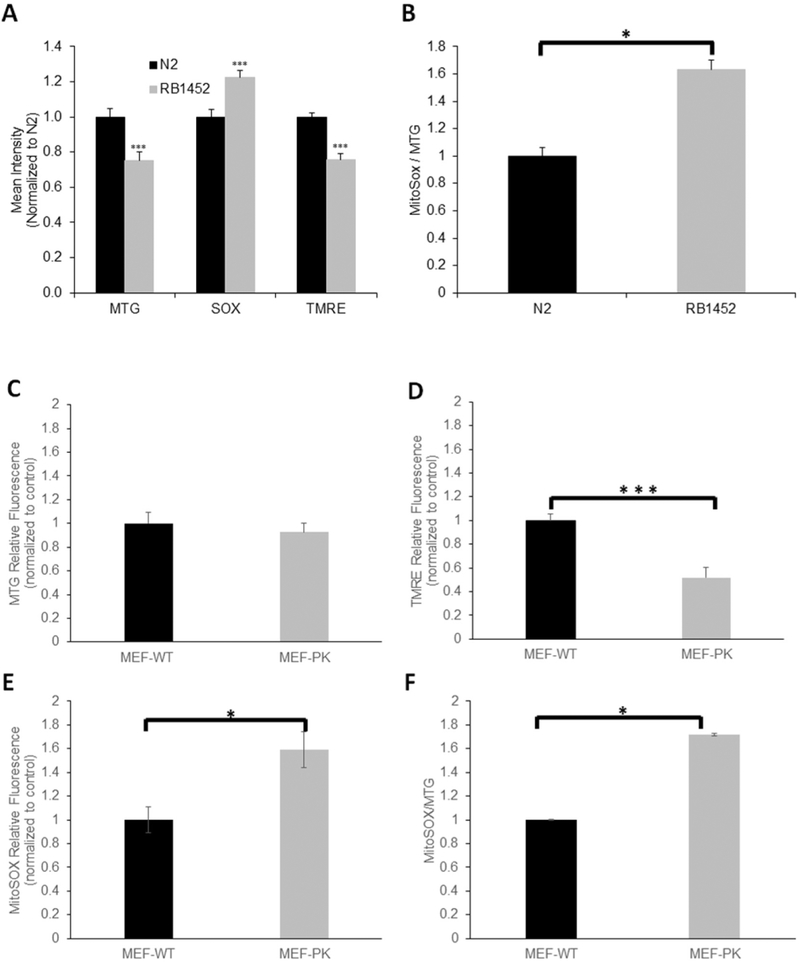

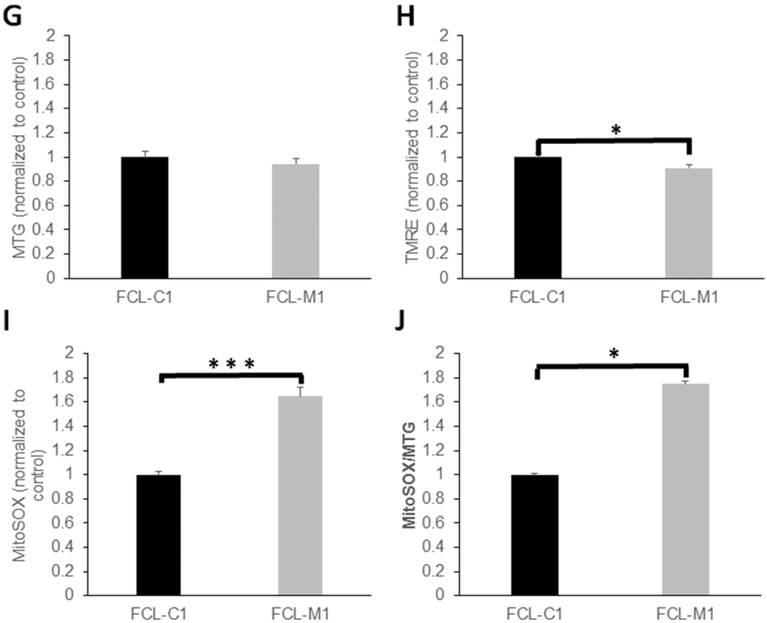

We sought to evaluate whether loss of NGLY1 expression and enzymatic activity (where NGLY1 activity was only assessed as described above in NGLY1−/− MEFs) impairs mitochondrial function. Relative fluorescence quantitation with MitoTracker Green (MTG), tetra-methylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), and MitoSOX Red was performed to assess, respectively, mitochondrial content, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondrial matrix oxidative burden by Biosorter (Copas) in living C. elegans worms and by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) in MEFs and human fibroblasts. Relative to wild-type C. elegans worms, NGLY1-knockout worms (RB1452) had 20% reduced mitochondrial content, 80% reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, and 20% increased mitochondrial oxidant burden (Fig. 3A). When normalized for mitochondrial content, relative mitochondrial matrix oxidative burden was even more pronounced in NGLY1-knockout C. elegans (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). No difference was seen in mitochondrial content of MEF-PK fibroblasts relative to MEF-WT control cell lines (Fig. 3C). However, mitochondrial membrane potential normalized to mitochondrial content was significantly decreased by 50% in NGLY1−/− MEF-PK cells compared to MEF-WT control cells (Fig. 3D). Matrix oxidative burden was significantly increased by > 50% in NGLY1−/− MEF-PK cells relative to control cells, with 40% increase in matrix oxidant burden seen when normalizing to mitochondrial content (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3E–F). Similar to findings in MEFs, no difference in mitochondrial content was seen in NGLY1-deficient human fibroblasts FCL-M1 relative to healthy controls FCL-C1 (Fig. 3G). However, when NGLY1 disease human fibroblasts were grown in galactose (stressing OXPHOS), alterations were seen minimally at the level of reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (9% decrease, p = 0.014) (Fig. 3H) and more pronounced at the level of increased matrix oxidant burden (65% increase, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3I). When normalized for relative mitochondrial content (MTG fluorescence), NGLY1 disease human fibroblast MitoSOX fluorescence was 74% increased (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3J). These data suggest that NGLY1 deficiency in human fibroblasts leads to mild mitochondrial RC dysfunction with pronounced increase in mitochondrial oxidative stress. Collectively, evaluating mitochondrial effects of NGLY1 deficiency in models from three species show modestly reduced mitochondrial content occurs in C. elegans, with significant reductions in mitochondrial membrane potential and increased mitochondrial oxidant burden in all three NGLY1-deficient models studied.

Fig. 3. Mitochondrial physiologic parameters relative quantitation in NGLY1-deficient C. elegans, MEFs, and human fibroblasts.

(A) In vivo fluorescence microscopic analysis of relative mitochondrial content (MTG), mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE), and mitochondrial oxidative burden (MitoSox) in NGLY1 deficient mutant (RB1542) and wild-type (N2 Bristol) C. elegans. n = 3 biological replicate experiments performed. (B) MitoSOX fluorescence was normalized to total mitochondrial content in RB1542 and wild-type C. elegans. n = 3 biological replicate experiments performed. (C–F) FACS analysis of mitochondrial physiology in NGLY1-deficient and wild-type (WT) MEFs, in 100,000 cells per condition. MEF-WT and MEF-PK mitochondrial content (MTG) (C), mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE) (D) and mitochondrial superoxide burden (MitoSOX) (E) are shown, as well as relative superoxide burden normalized to mitochondrial content (F). n = 3 biological replicate experiments performed per condition. (G–J) FACS analysis of mitochondrial physiology in NGLY1-deficient and healthy control human fibroblasts, in 100,000 cells per condition. Human fibroblast line mitochondrial content (MTG) (G), mitochondrial membrane potential normalized to mitochondrial content (TMRE/MTG) (H), mitochondrial superoxide burden (I), and mitochondrial superoxide burden normalized to mitochondrial content (MitoSOX/MTG) (J) are shown, with individual cell line identified by labels detailed in Table 1. Bars in all panels represent mean and standard error of mean fluorescence intensities in three biological replicate experiments normalized to the average fluorescence measured in the control cell line. Differences between groups were statistically analyzed by Student’s t-test (two-way, unequal variance). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

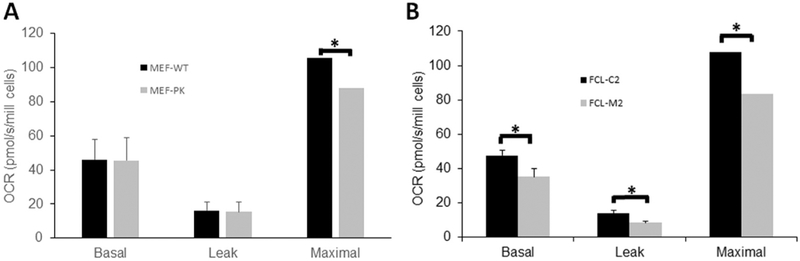

3.5. Reduced mitochondrial respiradon occurred both in Ngly1-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts and in NGLY1-deficient human fibroblasts

Evaluation of cellular oxygen consumption as an indicator of integrated OXPHOS capacity using high-resolution respirometry (Oxygraph-2k, Oroboros) in intact cells was performed in Ngly1-deficient MEFs (Fig. 4A) and human NGLY1 disease fibroblasts (Fig. 4B). Ngly1-knockouts MEF-PK cells had normal basal respiration, which indicates integrated activity of all five RC complexes. Non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption (‘leak’) capacity as determined by the addition of oligomycin to inhibit complex V-based ATP synthesis was also unchanged in MEF-PK cells. However, when the proton ionophore carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) was added, which uncouples the inhibited complex V from the rest of the electron transport system (i.e., complexes I-IV) to reach maximal oxygen consumption rates, significant reduction in the maximal respiratory capacity of MEF-PK cells was seen (Fig. 4A, 16.5% reduction, p < 0.05). Interestingly, NGLY1 mutant human FCLs (M2) with severely reduced NGLY1 expression had a significant reduction in routine respiratory capacity (Fig. 4B, 25.7% reduction, p < 0.05); this difference may relate to differences in mutation severity or species-specific effects of NGLY1 deficiency. NGLY1 mutant human FCLs also showed a similar degree of impairment as MEF-PK cells in maximal (uncoupled) respiratory capacity (Fig. 4B, 22.6% reduction, p < 0.001). Together, these data demonstrate that both mouse and human fibroblasts with severe NGLY1 deficiency have a significant reduction in their maximal mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity, in addition to reduced basal respiratory capacity in the human NGLY1 disease fibroblasts.

Fig. 4. NGLY1 deficient MEF and human fibroblast cells have reduced mitochondrial respiratory capacity.

Mean oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were quantified in intact cells corresponding to basal (routine, representing complex I–V integrated respiratory capacity), leak (oligomycin-inhibited, representing non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption), and maximal (FCCP-uncoupled, representing complex I-IV respiratory capacity of the electron transport system) states. Bar graphs convey mean and standard error for oxygen (O2) consumption rate per cell across 3 biological experiments performed. (A)NGLY1 deficient MEFs (MEF-PK) had 16.5% reduced maximal oxygen consumption capacity relative to MEF-WT control cells. *, p < 0.05. (B) NGLY1 disease human fibroblasts (FCL-M2) had 25.7% reduced basal and 22.6% reduced maximal oxygen consumption capacity relative to wild-type control (FCL–C2). *, p < 0.05.

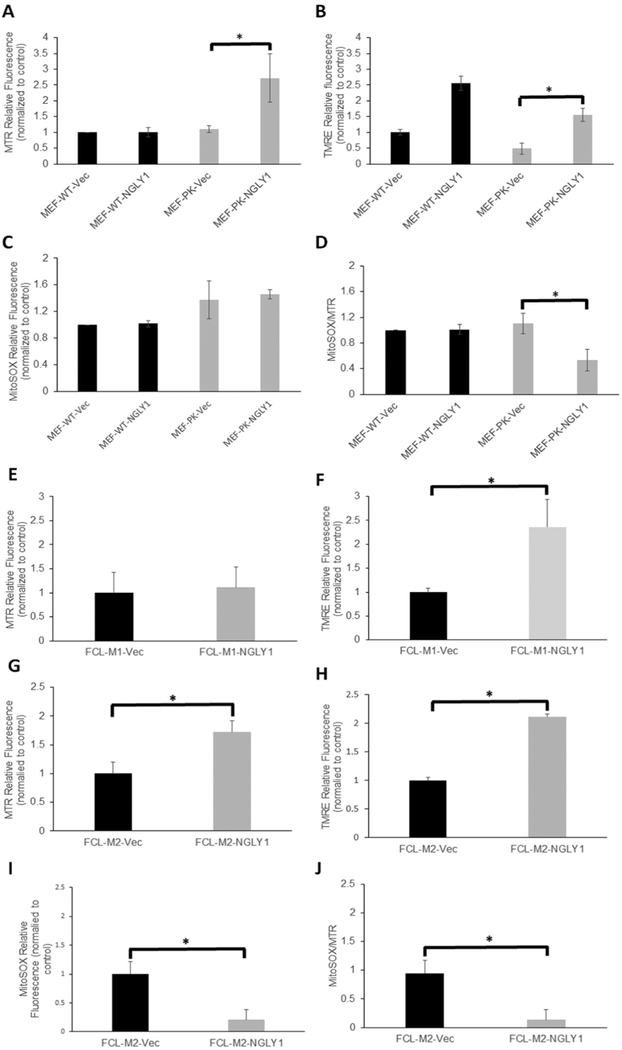

3.6. Rescuing NGLY1 expression in NGLY1-deficient MEF and human fibroblast cells restored mitochondrial physiology

In vitro rescue using lentiviral cDNA expression was performed in NGLY1-deficient MEFs (Fig. 5) and two human NGLY1 disease fibroblast cell lines (data not shown). Specifically, MEF-WT and MEF-PK (NGLY1−/−) cells were each infected with lentiviral human NGLY1 cDNA as well as corresponding empty vector control, followed by puromycin selection. Brightly fluorescent cells were selected that were double-positive for both green fluorescence protein (GFP) expression and puromycin resistance. Based on the intensity of their GFP fluorescence, cells were sorted using flow cytometry into dim (D) and bright (B) fluorescence groups, differing by > 10-fold (Fig. 5A). NGLY1 mRNA expression was upregulated in cDNA rescued cells, where the brighter GFP fluorescence intensity directly correlated with higher Ngly1 expression (Fig. 5B). Thus, we successfully established NGLY1 cDNA-rescued cells as a means to evaluate whether this would reverse the observed changes in mitochondrial physiology, focusing on evaluation of mitochondrial membrane potential by FACS analysis and cellular oxygen consumption capacity by high-resolution respirometry analysis. Ectopic NGLY1 expression with dim GFP brightness in MEF-PK cells induced mitochondrial content as assessed by MTR (MitoTracker Deep Red) staining, with a nearly 2.5 fold increase in mitochondrial content compared with controls (Fig. 6A, p < 0.05). Mitochondrial membrane potential as assessed by relative TMRE fluorescence quantitation was increased by ectopic NGLY1-expression in both WT-Ngly1 and MEF-PK-Ngly1 cells (Fig. 6B, p < 0.05), demonstrating that NGLY1 overexpression directly increases mitochondrial membrane potential in all cells, even in the setting of unchanged mitochondrial content. Stable NGLY1-expression did not appear to change MitoSox relative fluorescence relative to vector control (Fig. 6C), but significantly decreased mitochondrial oxidant burden when assessed by relative quantitation of MitoSOX fluorescence normalized to MitoTracker Deep Red fluorescence as an indicator of mitochondrial content that was increased by ectopic NGLY1-expression in these cells (Fig. 6D, 51.7% change, p < 0.05). Similar studies performed in NGLY1 disease human fibroblasts FCL-M1 and FCL-M2 showed ectopic NGLY1-expression had comparable effects on mitochondrial physiology as seen in MEF-PK cells. In FCL-M1 cells, there was no change in mitochondrial content (Fig. 6E), but greater than 2-fold increase in mitochondrial membrane potential compared to empty-vector control (Fig. 6F, p < 0.05). When normalized to mitochondrial content (MTG), there was a 2-fold increase in mitochondrial membrane potential in these cells (p < 0.002). FCL-M1 did not have altered MitoSOX fluorescence relative to empty vector FCL control (data not shown). Studies in a second human NGLY1 disease human fibroblast line, FCL-M2, confirmed these changes in mitochondrial physiology, with 72% increase in relative mitochondrial content (Fig. 6G, p < 0.05), 2.1-fold increase in mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 6H, p < 0.05), as well as an approximate 80% reduction in mitochondrial matrix oxidant burden both when assessed relative to empty-vector rescued FCLs (Fig. 6I, p < 0.05), as well as when normalized to increased mitochondrial content (Fig. 6J, 85% change, p < 0.05). Thus, NGLY1 cDNA rescue increased not only NGLY1 expression but also restored mitochondrial physiology in Ngly1-deficient MEF and two human NGLY1 disease fibroblast lines. Specifically, this included significantly increased mitochondrial content in MEF and FCL-M2 disease lines, significantly increased mitochondrial membrane potential in wild-type as well as both FCL-M1 and FCL-M2 disease lines, and reduction of increased mitochondrial oxidant burden in MEF and FCL-M2 disease lines.

Fig. 5. NGLY1 expression in lentiviral-rescued MEF Ngly1−/− cells.

MEF-PK and MEF-WT cells were each Infected with either NGLY1-cDNA or control empty lentiviral cDNA vector, with puromycln resistance and GFP fluorescence used to monitor viral Infection and gene expression. (A) GFP expression of lentiviral vectors In MEF-WT (left panel) and MEF-PK (right panel) cell lines. FACS-sorted cells were collected in groups representing dim (D, blue line) and bright (B, red line) fluorescent populations based on their relative GFP signal intensity. (B) NGLY1 expression level determined by qRT-PCR and expressed as fold-change relative to non-transfected control line in empty vector (V) pLenti-NGLY1-GFP (PK-N-D = dim; PK-N-B = bright) cells, n = 3 biological replicate experiments performed. ***, p < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 6. Ectopic NGLY1 expression rescued mitochondrial physiology alterations in NGLY1 deficient MEFs and human fibroblasts.

(A–D) FACS analysis of mitochondrial physiology in Ngly1 deficient (MEF-PK) and wild-type (MEF-WT) each transfected with empty vector and pLenti-NGLY1-CMV in 100,000 cells per condition. In all four MEF lines, mitochondrial content (MTR) (A), mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE) (B), mitochondrial superoxide burden (MitoSOX) (C), and relative mitochondrial superoxide burden normalized to mitochondrial content (MitoSox/MTR) (D) are shown. (E-K) In two different NGLY1 deficient human fibroblast lines (FCL-M1 and FCL-M2), FACS analysis was performed to quantify relative mitochondrial content (MTR) (E, G), mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE) (F, H), mitochondrial oxidant burden (MitoSOX) (I), and mitochondrial oxidant burden normalized for mitochondrial content (J) in fibroblasts from both subjects with plenti-NGLY1-CMV cDNA vector, empty vector, or non-transfected control cells. Results in all panels are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity ± standard error of the mean. 3 biological replicate experiments were performed per fluorescent dye and cell line. Differences between groups were statistically analyzed by Student’s t-test (two-way, unequal variance). *, p < 0.05.

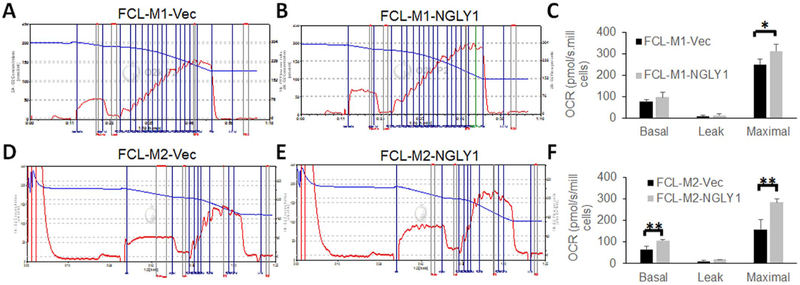

Finally, we evaluated whether NGLY1 overexpression might rescue the reduced cellular oxygen consumption capacity that occurred in human NGLY1-deficient fibroblast cells. Specifically, both FCL-M1 and FCL-M2 lines were evaluated with high-resolution respirometry by comparing each mutant cell transfected with empty vector to the same cell line transfected with NGLY1 cDNA in glucose-free galactose media that forced cellular reliance on mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity (Fig. 7). The increase seen with NGLY1 cDNA rescue in basal respiratory capacity was statistically significant in FCL-M2 (68.4% increased, p < 0.01) but not in FCL-M1 cells. In both FCL-M1 (Fig. 7A–C) and FCL-M2 (Fig. 7D–F) human NGLY1 disease fibroblast cell lines, significant improvements in maximal oxygen consumption capacity were seen with NGLY1 cDNA rescue (24.9% increase, p < 0.01 in FCL-M1; 79% increase, p < 0.05 in FCL-M2). Therefore, NGLY1 overexpression partially improved maximal cellular oxygen capacity in two different NGLY1 disease human fibroblast lines.

Fig. 7. Ectopic NGLY1-expression rescued mitochondrial respiratory capacity in NGLY1 deficient human fibroblasts.

Mean oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in basal, leak, and maximal states were quantified by high-resolution respirometry, as detailed in Fig. 4 Legend, for two NGLY1 disease subject human lines (FCL-M1 and FCL-M2, with mutations as detailed in Table 1), comparing empty vector control (panels A and D) transfected cells to pLenti-NGLY1-CMV cDNA vector transfected cells (panels B and E). The bar graphs in panels C and F indicate the mean and standard error oxygen consumption rate across three biological experiments performed per cell line. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

While mitochondrial RC diseases (Haas et al., 2007) and congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) (Jaeken, 2011) share extensive overlap in clinical features, each with a vast array of multi-systemic involvement, their cellular pathophysiology has classically been considered distinct. Here, we demonstrate that there exists an essential physiologic connection between cellular N-deglycosylation capacity and mitochondrial function. Indeed, we explore an unexpected connection between the pathophysiology of primary RC disease and that of a new CDG subtype caused by NGLY1 deficiency, which originated in a clinical observation of dysregulated mitochondria in liver and muscle tissue biopsies from two young children with NGLY1 disease. NGLY1 encodes an N-glycan glycosidase that functions as a cytosolic enzyme to removes N-glycans from asparagine (Asn) residues of unwanted N-glycoproteins once marked for disposal by the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway (Suzuki and Harada, 2014). Following N-glycan removal from severely misfolded proteins by NGLY1, free glycans are transported to the lysosome for degradation, while free proteins (and to a lesser extent, glycoproteins) are redirected to the proteasome for degradation (Chantret and Moore, 2008; Ninagawa et al., 2015). Despite its enzymatic activity, NGLY1 has been shown to have a non-essential role in the ERAD pathway (Chantret et al., 2010; Hirsch et al., 2003; Misaghi et al., 2004). In contrast, our data demonstrates that NGLY1 function is necessary to maintain normal mitochondrial function.

Several NGLY1 human disease subjects have evidence, either in their tissues and/or in their primary fibroblast cell lines, of dysregulated mitochondrial content and RC function. Specifically, cellular studies demonstrated reduced mitochondrial membrane potential along with increased mitochondrial oxidant burden, which were rescued with lentiviral-based NGLY1 cDNA rescue that restored NGLY1 expression that we showed in two different human NGLY1 disease fibroblast cell lines. A similar pattern that included mitochondrial depletion along with reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and increased mitochondrial oxidant stress was evident in a short-lived C. elegans NGLY1-knockout strain. Finally, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from a lethal Ngly1-knockout mouse (Suzuki et al., 2003) also showed reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and increased mitochondrial oxidant burden, alterations that were normalized in both MEFs and human disease fibroblasts by lentiviral-based NGLY1 cDNA rescue that restored NGLY1 expression. That NGLY1 deficiency should negatively impact mitochondrial mass and/or RC function in distinct evolutionary species is surprising and significant, given that mitochondria have not been known to have either NGLY1 expression (nor did we observe mitochondria-localized NGLY1 expression, data not shown) or N-glycosylated proteins within the RC (Zielinska et al., 2010). Interestingly, several in depth glycoproteomic studies of human or mouse whole tissues have documented the existence of N-linked glycosylated forms of several known mitochondrial proteins (Fang et al., 2016). These included several subunits from the mitochondrial protein import complex, including Tomm40, Tomm6, and Tom70a, possibly implicating N-glycosylation or N-deglycosylation in the regulation of mitochondrial proteins. Further studies are underway to verify the existence and extent of N-linked glycosylation on specific mitochondria-localized proteins, which may provide a mechanistic connection between NGLY1 and mitochondrial physiology.

Remarkably, the complementary relationship of NGLY1 activity being essential for cellular adaptation to primary RC dysfunction also appears to exist. Our recent transcriptome meta-analysis of diverse genetic causes of human RC disease revealed NGLY1 to be the second-most upregulated gene (Zhang and Falk, 2014), a finding we have validated by western immunoblot analysis showing increased NGLY1 expression in RC disease patient cells (Fig. S3). Furthermore, we showed here that fibroblast cells with NGLY1 deficiency cannot sustain direct RC inhibition (Fig. 1B). Thus, cellular N-deglycosylation capacity appears to be a key factor in RC disease pathogenesis, where too little NGLY1 activity impairs RC function, and cellular adaptation to primary RC dysfunction requires upregulated NGLY1 activity. Interestingly, ectopic NGLY1 expression significantly increased mitochondrial membrane potential not only in Ngly1-deficient MEF cells, but also in wild-type MEF cells (Fig. 6B), suggesting that NGLY1 modulation may offer a potential therapeutic strategy for mitochondrial RC disease.

5. Conclusion

NGLY1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial physiology in diverse invertebrate (C. elegans) and vertebrate (mouse and human) evolutionary species, causing a modest reduction in mitochondrial content in C. elegans and more consistent significant reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential and significant increase in mitochondrial matrix oxidant burden across all 3 species studied. Maximal cellular mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity was also consistently reduced in both MEF and C. elegans genetic knockout models of NGLY1 deficiency. That these changes are specific to NGLY1 deficiency is confirmed by lentiviral rescue studies in both human fibroblasts and MEFs that restore NGLY1 expression and rescue the mitochondrial phenotypes. Overall, NGLY1 expression and likely its related cytosolic N-glycan deglycosylase capacity appears to be a significant and previously unappreciated factor in RC disease pathogenesis. Specifically, too little NGLY1 expression impairs RC function, while conversely, cellular adaptation to primary RC dysfunction requires upregulated NGLY1 expression. Further mechanistic investigations are needed within the nascent field of cellular and mitochondrial N-glycomics to further understanding of disease pathogenesis that may enable the development of effective therapies for RC diseases and CDG.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the NGLY1 disease families who participated in this research study; Rui Xiao, PhD, for providing statistical assistance with analysis of C. elegansfluorescence data; Lynne Wolfe, MS, CRNP, BC, and William Gahl, MD, PhD, at the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health for generously sharing human NGLY1 disease deidentified fibroblast cell lines; as well as Tadashi Suzuki, PhD, of Riken Institute in Japan for generously sharing MEF cells from NGLY1 knockout and control mice. This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM115730 to M.J.F., Y.A., M.H, and E.O.) and a generous research grant from the Grace Wilsey Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders or National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans

- CDG

congenital disorders of glycosylation

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

ER-associated degradation

- ERAF

ER-associated folding

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone

- FCL

fibroblast cell line; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MTG

MitoTracker Green

- MTR

MitoTracker Deep Red

- NGM

nematode growth media

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- RC

respiratory chain

- TMRE

tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Author contributions

J. Kong and Y. Argon (NGLY1 gene and protein expression studies, lentiviral cDNA rescue in MEFs and FCLs), J. Kong and M. Peng (human and mouse cell mitochondrial characterization including FACS, respirometry, and viability analyses), J. Ostrovsky and O. Oretsky (C. elegans lifespan studies), M. Peng (C. elegans png-1 deletion analysis), Y. J. Kwon (C. elegans fluorescence studies), E. McCormick and M. J. Falk (human NGLY1 disease subject evaluation and IRB consent), and M.J. Falk, Y. Argon, and M. He (conceived and co-directed project). The manuscript was written by J. Kong, M. Peng, and M.J. Falk, with contributions, review, and final approval by all authors.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2017.07.008.

References

- Caglayan AO, Comu S, Baranoski JF, Parman Y, Kaymakcalan H, Akgumus GT, Caglar C, Dolen D, Erson-Omay EZ, Harmanci AS, Mishra-Gorur K, Freeze HH, Yasuno K, Bilguvar K, Gunel M, 2015. NGLY1 mutation causes neuromotor impairment, intellectual disability, and neuropathy. Eur. J. Med. Genet 58, 39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantret I, Moore SE, 2008. Free oligosaccharide regulation during mammalian protein N-glycosylation. Glycobiology 18, 210–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantret I, Fasseu M, Zaoui K, Le Bizec C, Yaye HS, Dupre T, Moore SE, 2010. Identification of roles for peptide: N-glycanase and endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase (Engase1p) during protein N-glycosylation in human HepG2 cells. PLoS One 5, e11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingley S, Polyak E, Lightfoot R, Ostrovsky J, Rao M, Greco T, Ischiropoulos H, Falk MJ, 2010. Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction variably increases oxidant stress in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Mitochondrion 10, 125–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingley S, Chapman KA, Falk MJ, 2012. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of mitochondrial content, membrane potential, and matrix oxidant burden in human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Methods Mol. Biol 837, 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns GM, Shashi V, Bainbridge M, Gambello MJ, Zahir FR, Bast T, Crimian R, Schoch K, Platt J, Cox R, Bernstein JA, Scavina M, Walter RS, Bibb A, Jones M, Hegde M, Graham BH, Need AC, Oviedo A, Schaaf CP, Boyle S, Butte AJ, Chen R, Chen R, Clark MJ, Haraksingh R, Consortium FC, Cowan TM, He P, Langlois S, Zoghbi HY, Snyder M, Gibbs RA, Freeze HH, Goldstein DB, 2014. Mutations in NGLY1 cause an inherited disorder of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. Genet. Med 16, 751–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang P, Wang XJ, Xue Y, Liu MQ, Zeng WF, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Gao X, Yan GQ, Yao J, Shen HL, Yang PY, 2016. In-depth mapping of the mouse brain N-glycoproteome reveals widespread N-glycosylation of diverse brain proteins. Oncotarget 7, 38796–38809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH, Eklund EA, Ng BG, Patterson MC, 2015. Neurological aspects of human glycosylation disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 38, 105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai X, Ghezzi D, Johnson MA, Biagosch CA, Shamseldin HE, Haack TB, Reyes A, Tsukikawa M, Sheldon CA, Srinivasan S, Gorza M, Kremer LS, Wieland T, Strom TM, Polyak E, Place E, Consugar M, Ostrovsky J, Vidoni S, Robinson AJ, Wong LJ, Sondheimer N, Salih MA, Al-Jishi E, Raab CP, Bean C, Furlan F, Parini R, Lamperti C, Mayr JA, Konstantopoulou V, Huemer M, Pierce EA, Meitinger T, Freisinger P, Sperl W, Prokisch H, Alkuraya FS, Falk MJ, Zeviani M, 2013. Mutations in FBXL4, encoding a mitochondrial protein, cause early-onset mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet 93, 482–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman GS, Chinnery PF, DiMauro S, Hirano M, Koga Y, McFarland R, Suomalainen A, Thorburn DR, Zeviani M, Turnbull DM, 2016. Mitochondrial Diseases. 2. Nature Reviews Disease Primerspp 16080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotzke JE, Lu Q, Cresswell P, 2013. Deglycosylation-dependent fluorescent proteins provide unique tools for the study of ER-associated degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 3393–3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas RH, Parikh S, Falk MJ, Saneto RP, Wolf NI, Darin N, Cohen BH, 2007. Mitochondrial disease: a practical approach for primary care physicians. Pediatrics 120, 1326–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig SM, 2013. Basic image analysis and manipulation in ImageJ. In: Current Protocols in Molecular Biology Chapter 14, Unit14 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Grotzke JE, Ng BG, Gunel M, Jafar-Nejad H, Cresswell P, Enns GM, Freeze HH, 2015. A congenital disorder of deglycosylation: biochemical characterization of N-glycanase 1 deficiency in patient fibroblasts. Glycobiology 25, 836–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch C, Blom D, Ploegh HL, 2003. A role for N-glycanase in the cytosolic turnover of glycoproteins. EMBO J. 22, 1036–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Harada Y, Hosomi A, Masahara-Negishi Y, Seino J, Fujihira H, Funakoshi Y, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Suzuki T, 2015. Endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase forms N-GlcNAc protein aggregates during ER-associated degradation in NGLY1-defective cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 1398–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeken J, 2011. Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG): it’s (nearly) all in it!. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis 34, 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam C, Ferreira C, Krasnewich D, Toro C, Latham L, Zein WM, Lehky T, Brewer C, Baker EH, Thurm A, Farmer CA, Rosenzweig SD, Lyons JJ, Schreiber JM, Gropman A, Lingala S, Ghany MG, Solomon B, Macnamara E, Davids M, Stratakis CA, Kimonis V, Gahl WA, Wolfe L, 2017. Prospective phenotyping of NGLY1-CDDG, the first congenital disorder of deglycosylation. Genet. Med 19, 160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack S, Polyak E, Ostrovsky J, Dingley SD, Rao M, Kwon YJ, Xiao R, Zhang Z, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Falk MJ, 2015. Pharmacologic targeting of sirtuin and PPAR signaling improves longevity and mitochondrial physiology in respiratory chain complex I mutant Caenorhabditis Elegans. Mitochondrion 22, 45–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misaghi S, Pacold ME, Blom D, Ploegh HL, Korbel GA, 2004. Using a small molecule inhibitor of peptide: N-glycanase to probe its role in glycoprotein turnover. Chem. Biol 11, 1677–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninagawa S, Okada T, Sumitomo Y, Horimoto S, Sugimoto T, Ishikawa T, Takeda S, Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kamiya Y, Kato K, Mori K, 2015. Forcible destruction of severely misfolded mammalian glycoproteins by the non-glycoprotein ERAD pathway. J. Cell Biol 211, 775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Ostrovsky J, Kwon YJ, Polyak E, Licata J, Tsukikawa M, Marty E, Thomas J, Felix CA, Xiao R, Zhang Z, Gasser DL, Argon Y, Falk MJ, 2015. Inhibiting cytosolic translation and autophagy improves health in mitochondrial disease. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 4829–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, 2015. The cytoplasmic peptide:N-glycanase (NGLY1)-basic science encounters a human genetic disorder. J. Biochem 157, 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, 2016. Catabolism of N-glycoproteins in mammalian cells: molecular mechanisms and genetic disorders related to the processes. Mol. Asp. Med 51, 89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Harada Y, 2014. Non-lysosomal degradation pathway for N-linked glycans and dolichol-linked oligosaccharides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 453, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Kwofie MA, Lennarz WJ, 2003. NGLY1, a mouse gene encoding a deglycosylating enzyme implicated in proteasomal degradation: expression, genomic organization, and chromosomal mapping. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 304, 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Huang C, Fujihira H, 2016. The cytoplasmic peptide:N-glycanase (NGLY1) - structure, expression and cellular functions. Gene 577, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Falk MJ, 2014. Integrated transcriptome analysis across mitochondrial disease etiologies and tissues improves understanding of common cellular adaptations to respiratory chain dysfunction. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 50, 106–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska DF, Gnad F, Wisniewski JR, Mann M, 2010. Precision mapping of an in vivo N-glycoproteome reveals rigid topological and sequence constraints. Cell 141, 897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.