Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol (CBD) in healthy dogs. Thirty, healthy research dogs were assigned to receive 1 of 3 formulations (oral microencapsulated oil beads, oral CBD-infused oil, or CBD-infused transdermal cream), at a dose of 75 mg or 150 mg q12h for 6 wk. Serial cannabidiol plasma concentrations were measured over the first 12 h and repeated at 2, 4, and 6 wk. Higher systemic exposures were observed with the oral CBD-infused oil formulation and the half-life after a 75-mg and 150-mg dose was 199.7 ± 55.9 and 127.5 ± 32.2 min, respectively. Exposure is dose-proportional and the oral CBD-infused oil provides the most favorable pharmacokinetic profile.

Résumé

Le but de la présente étude était de déterminer la pharmacocinétique du cannbidiol (CBD) chez des chiens en santé. Trente chiens de recherche en santé ont été assignés à recevoir une des trois formulations (de l’huile micro-encapsulé dans des billes par voie orale, de l’huile infusé de CBD par voie orale, ou une crème infusée de CBD par voie transdermique), à une dose de 75 mg ou 150 mg q12h pendant 6 semaines. Les concentrations plasmatiques de cannabidiol ont été mesurées pendant les 12 premières heures et répétées après 2, 4 et 6 semaines. Les expositions systémiques les plus élevées ont été observées avec la formulation d’huile infusé de CBD administrée par voie orale et la demi-vie après une dose de 75 mg et de 150 mg était de 199,7 ± 55,9 et 127,5 ± 32,2 min, respectivement. L’exposition est proportionnelle à la dose et l’huile infusée de CBD par voie orale fournie le profile pharmacocinétique le plus favorable.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

Cannabis has been used for centuries in human medicine for both recreational and medicinal purposes. In human medicine, cannabis-based extracts have been used for the treatment of spasticity, central pain, lower urinary tract symptoms in multiple sclerosis, sleep disturbances, peripheral neuropathic pain, brachial plexus avulsion symptoms, nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, loss of appetite, rheumatoid arthritis, intractable cancer pain, spinal cord injuries, Tourette’s syndrome, psychoses, epilepsy, glaucoma, Parkinson’s disease, and dystonia (1–4). Although there are anecdotal success stories for treating many of the same diseases in pets, no scientific reports have been published to date (1,5–7). If cannabidiol (CBD) is shown to be measurable in canine plasma, further studies investigating the efficacy of CBD for various diseases, including chronic pain, neuropathic pain, epilepsy, appetite stimulation, and anxiety, could be considered.

The chemical substances isolated from Cannabis sativa, phytocannabinoids, are divided into the psychotropic group and non-psychotropic group (5). The major psychoactive constituent of C. sativa, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), causes toxicosis in dogs and is therefore of limited use in canine patients (8,9). The list of non-psychotropic compounds is expanding, but cannabidiol (CBD) is the most promising phytocannabinoid candidate, owing to its non-psychotropic effects, low toxicity, and high tolerability (10–13).

The purpose of this study was to determine the pharmacokinetics of orally and transdermally administered CBD and to compare the CBD plasma concentrations of 3 different delivery methods at 2 different dosages. We present a 3-part hypothesis: i) a single dose of CBD will result in measurable blood levels within 12 h; ii) daily administration of CBD will result in sustained blood levels; and iii) topical formulations for CBD delivery will have higher blood levels because of the elimination of the hepatic first-pass effect.

Materials and methods

Dogs

This study was carried out under the strict regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All aspects of this study were approved by Colorado State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol ID: 15-5782A, approved: February 19, 2016). A power calculation was conducted, which showed that 10 subjects in each dose group would achieve a statistical power of 80% with a minimum Cmax (maximum concentration) difference of 200 ng/mL between the groups with a standard deviation of 100 ng/mL. Thirty-one healthy adult, sexually intact male, purpose-bred research beagle dogs, from 4 to 5 y of age, weighing an average of 13 kg (9.5 to 16.2 kg) were evaluated. Upon arrival, the dogs were determined to be healthy through physical examinations carried out by either a Board-certified neurologist or a neurology resident and laboratory work, including complete blood (cell) count (CBC), chemistry panel, urinalysis, and pre- and postprandial bile acid assay. Animals were excluded if there was a comorbidity with a poor prognosis, abnormalities on blood work, or if they were currently receiving medications. Thirty dogs met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study; 1 dog was excluded based on abnormal blood work.

All animals were kept in an on-site research facility and were checked regularly for feeding, cleaning, and overall appearance. Each dog was housed in an individual run as space allowed; beyond that, they shared a run with 1 other compatible dog. All dogs were evaluated weekly by a veterinarian who conducted complete physical examinations, as well as twice-daily general health assessments by the animal care staff and veterinary students.

Treatment and sample collection

The CBD was provided and formulated by Applied Basic Science Corporation, a 3rd-party, contracted enterprise within the state of Colorado. A random number generator was used to randomly assign each dog to 1 of 3 CBD delivery methods as Group 1 (CBD-infused transdermal cream), Group 2 (oral microencapsulated oil beads), or Group 3 ( oral CBD-infused oil). Dogs in all 3 groups were then further divided into 2 different dosing groups (5 dogs/group) in an open-label study, to receive either 75 mg q12h (subgroup a) or 150 mg q12h (subgroup b) (Table I). All dogs were therefore administered a total daily dose of either 150 or 300 mg of CBD using 1 of the following delivery methods: CBD-infused transdermal cream (110 mg/mL) applied to the pinnae; beads of microencapsulated oil in capsules (microencapsulated oil beads; 25-mg and 50-mg capsule sizes); or CBD-infused oil (75 mg/mL or 150 mg/mL). The 2 doses corresponded with approximately 10 mg/kg body weight (BW) per day or 20 mg/kg BW per day. For the duration of the study, all dogs were administered each dose of CBD after a small meal.

Table I.

Dosing regimen for CBD administered to healthy beagle dogs.

| Group (5 dogs/group) | Delivery method | Approximate dose (mg/kg body weight per day) | Dose (mg q12h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | CBD-infused transdermal cream | 10 | 75 |

| 1b | CBD-infused transdermal cream | 20 | 150 |

| 2a | Microencapsulated oil beads | 10 | 75 |

| 2b | Microencapsulated oil beads | 20 | 150 |

| 3a | CBD-infused oil | 10 | 75 |

| 3b | CBD-infused oil | 20 | 150 |

In the first part of this 2-part study, CBD pharmacokinetics were measured during the initial 12 h of dose administration. Before the start of the study and after a 12-hour fast, an indwelling jugular catheter was placed and maintained throughout the pharmacokinetic (PK) blood draws or until it became non-patent, dislodged, or there were signs of irritation, in which case blood was collected percutaneously. Blood sampling for CBD plasma concentrations (1.3 mL) occurred before CBD was administered (0 min) and at times 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, 480, 600, and 720 min, for a total of 9 sample points. Each sample was placed into a lithium heparin microtube and immediately set on ice.

In the second part of the study, all dogs continued receiving a total daily dose of either 75 mg or 150 mg q12h of their respective delivery method, for a total of 6 wk. At 2, 4, and 6 wk after the first dose, blood was collected for CBD plasma concentrations. Each blood sample for CBD plasma levels was centrifuged for 10 min at 2000 × g and 8°C. The plasma was separated from the red blood cells, placed in a cryotube, and stored at −80°C until analysis at the end of the 6-week study period. Samples were spun and frozen within 2 h of collection.

Extraction of cannabidiol from plasma

The Colorado State University Proteomics and Metabolomics Laboratory measured the CBD plasma concentrations from 30 beagle dogs over 12 time points. Aliquots of plasma were stored at −80°C until time of extraction. For CBD extraction, plasma was thawed on ice and 50 μL of each sample was placed into a 2.0-mL glass extraction vial, kept chilled on ice. Two hundred microliters of cold (−20°C) 100% acetonitrile (spiked with 60 ng/mL of d3-CBD) was added to each sample and vortexed at room temperature for 5 min. Two hundred microliters of water were added and vortexed for an additional 5 min. One milliliter of 100% hexane was added to each sample and vortexed for a final 5 min. Phase separation was enhanced under centrifugation at 1000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The upper hexane layer was transferred to newly labeled glass vials (~ 900 μL per sample), carefully avoiding the middle and lower layers. Samples were concentrated to dryness under nitrogen gas (N2) and re-suspended in 60 μL of 100% acetonitrile.

Standard curve

Four, 10-point calibration curves of CBD were generated in matrix background using a pooled blank canine serum. Concentrations ranged from 1 ng/mL to 1600 ng/mL (2.5× dilution series). Fifty microliters of each fortified sample were extracted as described and 4 curves were generated to accommodate each day of data collection, as well as extraction day/batch.

Data collection and analysis

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was carried out on an Acquity UPLC (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) coupled to an Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters). Chromatographic separations were carried out on a Phenyl-Hexyl stationary phase column (1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μM, Waters). Mobile phases were 100% methanol (B) and 0.1% formic acid and water (A). The analytical gradient was as follows: time = 0 min, 0.1% B; time = 6 min, 97% B; time = 7.0 min, 97% B; time = 7.5 min, 0.1% B; time 12.0 min, 0.1% B. Flow rate was 200 μL/min and injection volume was 2 μL. Samples were held at 4°C in the autosampler and the column was operated at 70°C. Samples were directly injected into the mass spectrometer, which was operated in selected reaction monitoring mode, in which a parent ion was selected by the 1st quadrupole fragmented in the collision cell, then a fragment ion selected by the 3rd quadrupole. Productions, collision energies, and cone voltages were optimized for CBD and d3-CBD by direct injection of individual synthetic Cerilliant analytical reference standards. Inter-channel delay was set to 5 ms. The LC-MS was conducted in positive ionization mode with the capillary voltage set to 3.2 kV. Source temperature was 150°C and desolvation temperature was 500°C. Desolvation gas flow was 1000 L/h, cone gas flow was 150 L/h, and collision gas flow was 0.2 mL/min. Nebulizer pressure was set to 7 bar. Argon was used as the collision gas; otherwise nitrogen was used.

Calculation of CBD concentration in plasma

All raw data files were imported into Skyline (MacCoss Lab, Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington) and peak areas extracted for CBD and d3-CBD. Quantitation of analyte in plasma samples was based on linear regression of calibration curves and extrapolation using the analyte peak area to internal standard peak area ratios. All calibration curves were linear over the range of concentrations tested (r2 > 0.998). The limit of detection of the assay was 0.3 ng/mL and was calculated as the standard error divided by the slope of the linear regression of the calibration curves multiplied by 3.3. The limit of quantitation was 1 ng/mL and was determined as the lowest concentration within the linear portion of the calibration curves that had an accuracy within 15% of the nominal concentration. Accuracy and precision of the calibration curves were within 15%; the inter- and intra-day coefficient of variation was less than 5%.

Pharmacokinetic evaluation

The pharmacokinetic analysis was carried out by the Pharmacology Core Laboratory at the Colorado State University Flint Animal Cancer Center (Wittenburg). Non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis was carried out on the plasma CBD concentration-time data in all dosing groups using Phoenix WinNonlin Version 6.4 (Pharsight, Mountain View, California, USA) to obtain and compare pharmacokinetic parameters, determine dose proportionality, and predict pharmacokinetic parameters at different dose levels in each of the dosing formulations using nonparametric superposition. Parameters analyzed included maximal concentration (Cmax), area under the curve (AUC), half-life (T1/2), and dose-normalized values for Cmax and AUC.

Statistical analysis

All the outcome data on clinical significance were binary data. Contingency tables were constructed for each of the analyses and a Fisher’s exact test was conducted to evaluate significance between the formulations within each time point, as well as between the time points within each formulation for both doses of CBD. For some situations, in which all the subjects were in 1 group, no statistics could be done. For comparisons of the continuous data, such as the normalized peak area and CBD concentration between the formulation groups, a linear regression analysis was used, taking into account repeated measures across time points. The treatment effect was evaluated using the regression estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI). A P-value of 0.05 was considered to evaluate statistical significance for all analyses. SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used to analyze the data.

Results

CBD dosing formulations

Calculated concentrations of CBD in the various formulations were 142.0 mg/mL in the 150 mg/mL CBD-infused oil, 77.6 mg/mL in the 75 mg/mL CBD-infused oil, 103.0 mg/mL in the 110 mg/mL CBD-infused transdermal cream, and 36.0 mg/capsule in the 50-mg capsule and 17.2 mg/capsule in the 25-mg capsule of the microencapsulated oil bead formulation. Although CBD was not equal to 100% of its labeled dose, the variability was < 10% for the CBD-infused oil and CBD-infused transdermal cream formulations (9.4% for the 150 mg/mL CBD-infused oil, 3.5% for the 75 mg/mL CBD-infused oil, and 6.4% for the CBD-infused transdermal cream). However, the amount of CBD per capsule varied considerably from the labeled amount (28% for the 50 mg/capsule and 31.2% for the 25 mg/capsule).

Pharmacokinetic results

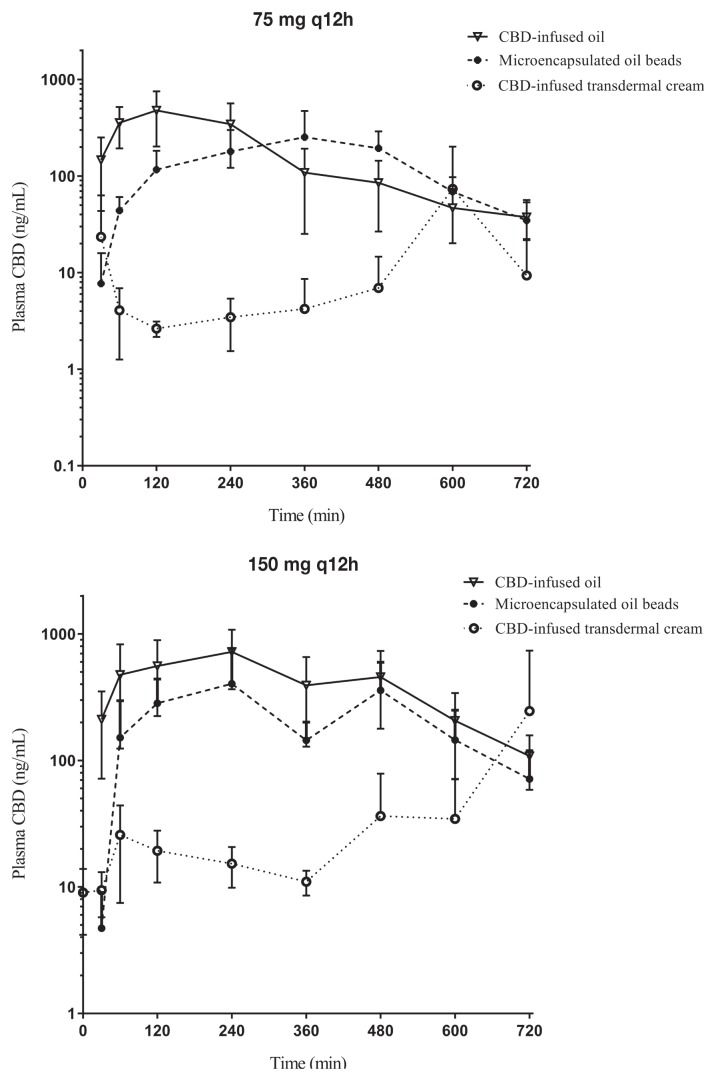

Of the 30 dogs enrolled in the study, all dogs successfully completed the study. Plasma CBD concentrations were determined at 8 time points over the first 12 h after the initial dose of each formulation (Figure 1). The elimination half-lives of CBD-infused oil, microencapsulated beads, and infused transdermal cream formulations given as a single dose of 75 mg and 150 mg are listed in Table II.

Figure 1.

Single-dose cannabidiol (CBD) plasma concentration. The 12-hour, single-dose CBD plasma concentration (mean +/− standard deviation) at 2 different dosages (75 mg, top; 150 mg, bottom) for transdermal cream, microencapsulated oil beads, and CBD-infused oil.

Table II.

Non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis of CBD plasma concentrations after a single dose of 75 mg or 150 mg using 3 different formulations.

| Parameter | Units | 75 mg | 150 mg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| CBD-infused oil | Micro-encapsulated | CBD-infused transdermal cream | CBD-infused oil | Micro-encapsulated | CBD-infused transdermal cream | ||

| Cmax | ng/mL | 625.3 ± 164.3 | 346.3 ± 158.7 | 74.3 ± 127.2 | 845.5 ± 262.2 | 578.1 ± 287.1 | 277.6 ± 476 |

| Cmax/dose | ng/mL | 110.1 ± 29.1 | 62.0 ± 30.3 | 11.3 ± 18.9 | 67.4 ± 14.9 | 51.3 ± 24.1 | 27.3 ± 48.5 |

| AUC0-T | min*μg/mL | 135.6 ± 46.3 | 98.0 ± 43.3 | 11.7 ± 18.9 | 297.6 ± 112.8 | 162.8 ± 61.2 | 29.7 ± 29.6 |

| AUC0-inf | min*μg/mL | 147.1 ± 49.4 | 103.5 ± 46.5 | ND | 317.4 ± 117.6 | 177.3 ± 58.5 | ND |

| AUC % extrapolated | 8.0 ± 3.0 | 5.0 ± 2.3 | ND | 6.5 ± 2.3 | 9.4 ± 5.5 | ND | |

| AUC0-inf/dose | min*μg/mL | 25.8 ± 8.6 | 18.2 ± 7.9 | ND | 25.2 ± 7.4 | 15.8 ± 5.1 | ND |

| MRT | Min | 217 ± 46 | 353 ± 48 | 490 ± 74 | 298 ± 43 | 332 ± 73 | 464 ± 123 |

| T1/2a | Min | 199.7 ± 55.9 | 95.4 ± 29.2 | ND | 127.5 ± 32.2 | 115.9 ± 88.6 | ND |

| Relative bioavailability | % | 100 | 70.1 | 8.6 | 100 | 54.7 | 9.9 |

Expressed as harmonic mean with pseudo-standard deviation. All other parameters are expressed as mean with standard deviation.

Cmax — maximal concentration; AUC — area under the curve; Cmax/dose and AUC0-inf /dose are the dose-normalized values for maximum plasma concentration and total exposure from time 0 to infinity, respectively; MRT — mean residence time; ND — not determined due to lack of elimination phase in the concentration-time profiles; T1/2 — half-life.

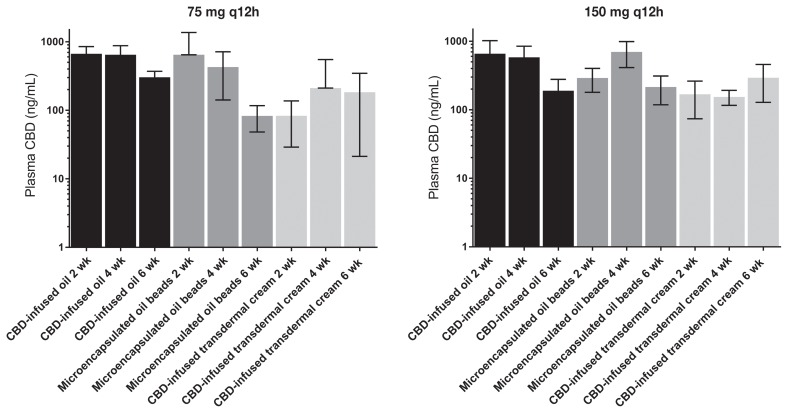

Blood was collected for CBD plasma concentrations at 2, 4, and 6 wk. Median maximum plasma CBD concentrations (ng/mL) were higher for dogs receiving the CBD-infused oil formulation. The median Cmax and standard deviation for each group at 75 mg q12h and 150 mg q12h were as follows: CBD-infused transdermal cream 30.10 + 127.18 and 97.46 + 476.10 ng/mL; microencapsulated oil beads 364.93 + 158.715 and 546.06 + 287.14 ng/mL; and CBD-infused oil 649.43 + 164.34 and 903.68 + 262.15 ng/mL, respectively. In addition, the overall exposure to CBD appeared to be dose-proportional in the CBD-infused oil formulation based on dose-normalized exposure values. The CBD-infused oil formulation appeared to have the smallest amount of inter-individual variability in plasma CBD exposure, as well as providing equal or greater plasma CBD exposures than the other 2 routes at each of the later time points (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cannabidiol (CBD) concentration at 6 wk. Maximal CBD plasma concentrations (mean +/− standard deviation) after twice-daily dosing for 2, 4, or 6 wk using 3 formulations. The lower dose (75 mg q12h) is represented on the left and the higher dose (150 mg q12h) on the right.

Inter-individual variability in exposures was assessed as the standard deviation divided by the mean of the dose normalized Cmax and AUC (Cmax/D and AUC0-inf/dose, respectively) of each formulation after the first dose at both dose levels. With respect to the dose-normalized Cmax values, in the 75 mg q12h cohort, the calculated inter-individual variability for the CBD-infused oil group was 26.4% versus 48.9% and 167% for the microencapsulated oil beads and CBD-infused transdermal cream, respectively. In the 150 mg q12h cohort, the calculated inter-individual variability in the CBD-infused oil group was 22.1% versus 47.0% and 178% for the microencapsulated oil beads and the CBD-infused transdermal cream groups, respectively. The same pattern held true for the inter-individual variability in dose-normalized AUC in which the calculated values for the CBD-infused oil group versus the microencapsulated oil beads (75 mg q12h dose) was 33.0% versus 43.4% (AUC0-inf could not be calculated in CBD-infused transdermal cream group due to lack of elimination phase). The inter-individual variability in AUC for the 150 mg q12h groups was found to be 29.4% and 32.3% in the CBD-infused oil versus microencapsulated beads, respectively.

A linear regression analysis taking repeated measures into consideration was used to evaluate the plasma CBD concentrations for each formula and its respective dose at 2, 4, and 6 wk. As normality was not met, the data were converted into log for analysis. With the exception of 2 wk in the 75 mg q12h group and 4 and 6 wk in the 150 mg q12h group, the plasma CBD levels were higher in the CBD-infused oil than in the other 2 formulations. No significant difference was detected at 4 and 6 wk in the 75 mg q12h group (P-values 0.078 and 0.066, respectively). However, the differences were significant (P-values < 0.05) at all remaining time points, doses, and formulations. At 6 wk in groups given 150 mg q12h of their respective formulation, there was no significant difference among the forms of medication.

Discussion

We describe the first pharmacokinetic study of oral and transdermal CBD in healthy dogs receiving a dose of either 75 mg q12h or 150 mg q12h. In this 2-part study, CBD pharmacokinetics were measured during the initial 12 h of a single dose administration. In the second part, all dogs continued receiving their respective doses and delivery methods for a total of 6 wk, during which time, plasma CBD levels were maintained until the study’s completion.

Bioavailability of CBD has been reported to be low when given orally to both dogs and humans, presumably due to high first-pass effect through the liver (14,15). Our hypothesis was that a transdermal route of administration would avoid first-pass effect from the liver. Although bioavailability could not be determined in this cohort of dogs, we demonstrated that the CBD-infused transdermal cream did not reach similar plasma concentrations as the other 2 formulations. In general, transdermal absorption may be incomplete because of diffusion barriers, such as thickness of the skin of the pinnae or absorptivity of the CBD-infused transdermal cream. Since CBD is highly lipophilic, it accumulates within the stratum corneum of human and rodent skin and does not penetrate deeper skin layers (16,17).

Pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated that the CBD-infused oil formulation resulted in higher maximal concentrations (Cmax) and systemic exposure (area under the curve; AUC) than the other 2 formulations (Table II). The oil formulation had the smallest amount of inter-individual variability in plasma CBD concentrations. This may be due, at least in part, to having less variation in the formulation. Regardless of cause, lower measurable plasma levels of CBD were evident in the CBD-infused transdermal cream group than in the groups given either of the other 2 formulations (Table II and Figure 1).

The half-lives (T1/2) reported in our study were shorter than those found in a previous crossover study evaluating plasma data in 6 dogs after intravenous administration of either 45 or 90 mg, followed by 180 mg orally (15). Terminal T1/2 ranged from 7 to 9 h in that study, but this was measured over 24 h after intravenous administration of CBD; the T1/2 of the oral dose could not be determined due to low or undetectable plasma levels. In the present study, CBD was not given via an intravenous route and sampling was carried out for 12 h following oral and transdermal doses. This difference in sampling duration may explain the longer T1/2 reported in the previous study, as this parameter is calculated by the slope of the terminal elimination phase, which tends to be more accurately represented the longer sampling can occur after drug administration.

Another limitation of this study is the short duration (6 wk) of CBD administration. Ideally, the dogs would be administered CBD for a longer period (several months at least) in order to assess whether the CBD concentrations remain stable, decrease, or increase over time.

Although we have demonstrated that CBD is absorbed orally, clinical trials are required to investigate its safety profile, to study its effectiveness in treating specific diseases, and to establish doses that provide therapeutic effects. Preferably, these studies would be conducted as prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Prenni, Lisa Wolfe, Hend Ibrahim, and Crystal Badger at the Proteomics and Metabolomics Laboratory, Colorado State University for their technical assistance in developing the CBD assay. This study was funded in full by Applied Basic Science Corporation, which is the manufacturer of the medication used. The sponsor was not involved in study design, analysis or storage of data, or manuscript preparation. Dr. Stephanie McGrath was a < 5% shareholder in Applied Basic Science Corporation for the duration of the study. As principal investigator, Dr. McGrath’s duties included developing the study design, conducting the study, and participating in data analysis and manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Ben Amar M. Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abel EL. Marihuana, The First Twelve Thousand Years. New York, New York: Plenum Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russo E, Guy GW. A tale of two cannabinoids: The therapeutic rationale for combining tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robson PJ. Therapeutic potential of cannabinoid medicines. Drug Test Anal. 2014;6:24–30. doi: 10.1002/dta.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podell M. Highs and lows of medical marijuana in the treatment of epilepsy. Proc Am Coll Vet Intern Med Forum. 2015:331–333. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal SK, Carter GT, Sullivan MD, ZumBrunnen C, Morrill R, Mayer JD. Medicinal use of cannabis in the United States: Historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5:153–168. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maa E, Figi P. The case for medical marijuana in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:783–786. doi: 10.1111/epi.12610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald KT, Bronstein AC, Newquist KL. Marijuana poisoning. Top Companion Anim Med. 2013;28:8–12. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godbold JC, Jr, Hawkins BJ, Woodward MG. Acute oral marijuana poisoning in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;175:1101–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espejo-Porras F, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Pertwee RG, Mechoulam R, Garcia C. Motor effects of the non-psychotropic phytocannabinoid cannabidiol that are mediated by 5-HT1A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2013;75:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill AJ, Williams CM, Whalley BJ, Stephens GJ. Phytocannabinoids as novel therapeutic agents in CNS disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones NA, Glyn SE, Akiyama S, et al. Cannabidiol exerts anticonvulsant effects in animal models of temporal lobe and partial seizures. Seizure. 2012;21:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunha JM, Carlini EA, Pereira AE, et al. Chronic administration of cannabidiol to healthy volunteers and epileptic patients. Pharmacology. 1980;21:175–185. doi: 10.1159/000137430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H, et al. Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuro-psychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55:791–802. doi: 10.1111/epi.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samara E, Bialer M, Mechoulam R. Pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol in dogs. Drug Metab Dispos. 1988;16:469–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry BW. Novel mechanisms and devices to enable successful transdermal drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;14:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodzki M, Godin B, Rakou L, Mechoulam R, Gallily R, Touitou E. Cannabidiol — Transdermal delivery and anti-inflammatory effect in a murine model. J Control Release. 2003;93:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]