Abstract

Resource constraints, value for money debates and concerns about provider behaviour have placed accountability ‘front and centre stage’ in health system improvement initiatives and policy prescriptions. There are a myriad of accountability relationships within health systems, all of which can be transformed by decentralisation of health system decision-making from national to subnational level. Many potential benefits of decentralisation depend critically on the accountability processes and practices of front-line health facility providers and managers, who play a central role in policy implementation at province, county, district and facility levels. However, few studies have examined these responsibilities and practices in detail, including their implications for service delivery. In this paper we contribute to filling this gap through presenting data drawn from broader ongoing research collaborations between researchers and health managers in Kenya and South Africa. These collaborations are aimed at understanding and strengthening day-to-day micropractices of health system governance, including accountability processes. We illuminate the multiple directions and forms of accountability operating at the subnational level across three sites. Through detailed illustrative examples we highlight some of the unintended consequences of bureaucratic forms of accountability, the importance of relational elements in enabling effective bureaucratic accountability, and the ways in which front-line managers can sometimes creatively draw upon one set of accountability requirements to challenge another set to meet their goals. Overall, we argue that interpersonal interactions are key to appropriate functioning of many accountability mechanisms, and that policies and interventions supportive of positive relationships should complement target-based and/or audit-style mechanisms to achieve their intended effects. Where this is done systematically and across key elements and actors of the health system, this offers potential to build everyday health system resilience.

Keywords: Health Policy, Health Systems, Qualitative Study

Key questions.

What is already known?

Accountability is recognised as being of critical importance in strengthening health systems and their performance.

There is limited understanding of the accountability responsibilities and practices of front-line providers and managers within decentralised systems.

What are the new findings?

Multiple directions and forms of accountability operate at the subnational level, but there is a dominance of bureaucratic accountability mechanisms.

To achieve the good intentions of bureaucratic accountability mechanisms, they require interpersonal processes between professionals and between professionals and others.

What do the new findings imply?

Policies and interventions supportive of positive relationships, and that build coproduction, should complement audit-style mechanisms to support positive system effects.

Introduction

Resource constraints, value for money debates and concerns about provider behaviour have placed accountability ‘front and centre stage’ in health system improvement initiatives and policy prescriptions.1 An accountability focus has also been propelled by limited gains in health system performance in many low-income/middle-income countries, combined with specific concerns about corruption, abuse of power, inadequate financial management and poor responsiveness to community priorities and concerns. The essence of accountability is answerability between sets of individuals (or ‘actors’) in relation to specific activities or interventions, enforced either with positive or negative sanctions, or by personal or professional ethics such as codes of conduct.2 Given the size and complexity of health systems, there are a myriad of accountability relationships between actors,3 with these relationships either ‘internal’ to health bureaucracies (such as between colleagues, juniors, managers, bosses or funders); or ‘external’, where those working in health bureaucracies answer to others outside these bureaucracies (such as facility users, community representatives or the general public).

Both internal and external accountability relationships can be transformed by decentralisation of health systems. In decentralisation, responsibilities, functions and resources are transferred from central to lower levels of government. Although there are different forms of decentralisation (eg, deconcentration, devolution and delegation), Mills4 mentions that they do not necessarily reflect different degrees of local autonomy. They do, however, denote different formal lines of accountability.4 Devolution may entail more significant decentralisation of political, fiscal and administrative decision-making authority and greater accountability to local populations than other forms of decentralisation. However, some degree of accountability to central government remains, and the balance of accountability between central government and local publics can cause tension.5 It is argued that the potential benefits of decentralisation include improved allocative and technical efficiency as a result of greater cost-consciousness and control at the local level, as well as strengthening quality, transparency, accountability and legitimacy due to greater possibility for user oversight and participation in decision-making.6 Such positive outcomes depend critically, however, on the accountability responsibilities and practices of front-line health facility providers and managers, who play a central role in policy implementation at the district and local levels.

Although accountability mechanisms ideally ensure that front-line health facility providers and managers are providing services that are efficient and responsive to communities, especially in decentralised systems, the literature suggests at least two potential accountability-related concerns. A first concern is that in delegating decision-making roles to the local level, governments often also apply increasingly stringent audit-style accountability requirements on these cadres of staff.3 Audit-style bureaucratic accountability requirements are relatively detailed, standardised and centralised approaches to accountability which are purportedly more uniform, objective, rigorous and transparent than more localised and face-to-face or ‘interpersonal’ forms.7 Although such accountability processes can be argued to build trust, facilitate public awareness and empowerment, and improve performance, there is also evidence from other contexts that these processes can be subject to game-playing, creative compliance, subjectivity and capacity constraints, thereby undermining their potential to achieve intended goals.8–10 In giving a false impression of trust, transparency and fairness, it has even been argued that these processes can be damaging to accountability goals.10 11 A second concern for front-line providers and managers is that in having to be accountable to many different actors within the system, they may be faced with conflicting demands, with negative potential implications for healthcare efficiency and responsiveness.8 12

Despite its importance, few studies have provided an indepth understanding of the accountability responsibilities and practices of front-line health facility providers and managers within decentralised systems, and the implications for service delivery. In this paper we contribute to filling this gap through presenting data drawn from broader ongoing research collaborations between researchers and health managers aimed at understanding and strengthening day-to-day micropractices of health system governance, including accountability processes, at the subnational level in Kenya and South Africa. Recognising the everyday decision-making and meaning-making of front-line actors,13 we argue that interpersonal or relational interactions are key to the appropriate functioning of many accountability mechanisms, and that policies and interventions supportive of positive interpersonal interactions should support target-based or audit-style mechanisms to achieve their positive intended effects.

Methods

Learning site settings and our analytical approach

We have been involved in three long-term collaborations between research teams and health system actors in specific districts in Kenya and South Africa. The three learning sites are embedded in two different national contexts and three, quite different local settings. The learning site approach, sites and settings have been described in some detail in our companion papers,14 15 but here we highlight the key points relevant for this paper.

In Kenya, considerable political, legislative and administrative decision-making power across sectors was devolved to 47 county governments within a 6-month time frame following the election of a new government in March 2013. This radical and speedy devolution of power represented a major break with the political and public management traditions of the country. In the health sector, county officials are now responsible for medical services, public health and primary healthcare (PHC)/promotion, with the national level responsible for health policy formulation and regulation functions, and national referral hospitals. Accountability structures and processes within counties have been and continue to be redrawn as a result, causing some confusion and conflict among mid-level managers. In South Africa, a similar form of decentralisation was instituted following the 1994 election of the first post-apartheid government. This led to provincial governments being responsible for the provision of all health services, the local government for a package of ‘municipal PHC services’, and the national government for developing overarching health policy and health legislation, and supporting specified prevention and disease control services. The District Health System has consistently been seen as the critical platform for strengthening PHC, but uncertainty about provincial and local government roles has, as in Kenya, provided an unstable context.

Within the two countries, we work in Kilifi County in Kenya, one of the 47 counties established within newly devolved national governance structures in 2013; and in South Africa, in two health districts located in different provinces (Sedibeng, Gauteng; and the Mitchells Plain area of the Metro District Health System/City of Cape Town, Western Cape i ). We have worked in Mitchells Plain since 2010, in Kilifi since 2012 and in Sedibeng since 2014. These sites were chosen because prior experience and engagement with managers provided a foundation for longer term collaboration. Sustained engagement was then made possible as research teams live locally and have maintained trusting relationships with health system colleagues over time. The three sites differ significantly from each other, with Kilifi being rural while the two South African sites are urban; they also have different population sizes, proportions living below the national poverty line and levels of prioritisation of health in budgetary allocations.

With regard to our study approach, the key features are as follows:

The overall study design is flexible, with an overall interest in understanding the daily routines and challenges of health managers at various levels of the district/county health system.

The study design evolves over the course of a long-term collaboration between health managers and researchers, where we have sought to gather information on and make sense of it with our colleagues, thereby coproducing knowledge.

The methods of data collection include document reviews, indepth interviews, group discussions, as well as observations; presenting and discussing ‘findings’ with managers (to test them and consider what managerial implications they have); and reflective discussions within the research teams.

Our data include, in addition to individual and group interview transcriptions and notes, reflective notes, journal data, presentations to managers, notes from feedback meetings and transcripts of our own reflective discussions.

For each site ethical approval was obtained from relevant national authorities and also from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

In this paper we draw on a range of data sources to examine the micropractices involved in the implementation of accountability mechanisms. As with our companion paper,14 we followed the principles adapted from case study research methodology and meta-synthesis. We, first, collectively read and reflected on accountability, then examined our data (both already published work and additional primary data), and finally, based on comparative analysis of experience across sites, developed an initial line of argument. A core team then prepared successive, draft manuscripts; and review, revision and paper finalisation involved further reflection among the cross-site authorship team. The cycles of reflection and multiple levels of triangulation achieved through this process underpin the trustworthiness of the resulting analysis.

In our analysis, we drew on two accountability frameworks in our efforts to unpack the forms of accountability observed and the factors that impact on them. This is in addition to the basic internal/external and bureaucratic/relational distinctions noted above.

Following Hupe and Hill,16 we draw on the idea that key actors may be accountable in various relations (bottom-up, top-down and ‘sideways’ to peers), and that front-line workers and managers are likely to engage with two quite contrasting forms of accountability: those that are more public-administrative and those that are professional-participatory. For the public-administrative forms of accountability, the mode of implementation is often target-driven towards performance. Examples are provided in box 1. Public-administrative forms of accountability are generally rule-bound or contractual relationships, where there is individual compliance to rules and targets, organisational conformity to standard operating procedures and contracts, and a general orientation towards achieving tasks or indicators. These more bureaucratic forms of accountability differ significantly from more professional-participatory accountability relationships, where the mode of implementation is more likely to be a form of coproduction among staff and with community/citizens/clients. These forms of accountability are often more trust-based, with individual compliance to internalised professional standards, organisational conformity to shared goals and standard setting, and a general orientation towards performance as achievement of wider public value. Of interest in our analysis is what forms of accountability are revealed in examining the micropractices of governance on the ground, including which forms are given higher priority, and what the implications of these practices are for individuals, the system and public health.

Box 1. Examples of internal bureaucratic accountability mechanisms in place in all three sites.

Staff performance appraisal.

Clinic supervision visits.

Quality of care audits.

Performance monitoring.

Service reports.

Monthly reports.

Financial management reports.

Budgeting processes.

Target setting meetings.

Facility statistics reports.

Disease programme reporting.

Procurement requirements.

Pharmaceutical supply reports.

From Cleary et al,17 we draw on the literature review finding that bureaucratic accountability mechanisms internal to health system hierarchies can constrain the functioning of external accountability mechanisms. For example, responding to the expectations of relatively powerful managers further up the system may constrain health providers’ efforts to respond to the needs of citizens and patients. Cleary et al 17 note that it is the interaction between bureaucratic and external accountability mechanisms that ultimately determines the extent to which the health system provides care to its citizens. If and how accountability processes support responsiveness to patients and citizens was found to be influenced by (1) the values, norms, institutions and culture of healthcare, versus citizens and patients; (2) the attitudes and perceptions of providers, managers, bureaucrats and policymakers, versus citizens and patients; and (3) the resources and capabilities of the health service, versus citizens and patients17. In our analysis we consider if and how internal bureaucratic accountability mechanisms are crowding out external accountability, and potential influences of accountability realities for responsiveness of healthcare to patients and citizens.

Results

Following an overview of the multiple directions and forms of accountability operating at the subnational level across the three learning sites, we give more detailed illustrations of the micropractices of accountability we observed, including some of the unintended consequences of bureaucratic forms of accountability, the importance of relational elements in enabling positive goals of bureaucratic accountability and the ways in which one set of accountability requirements can be creatively drawn on to challenge another.

Multiple directions and forms of accountability

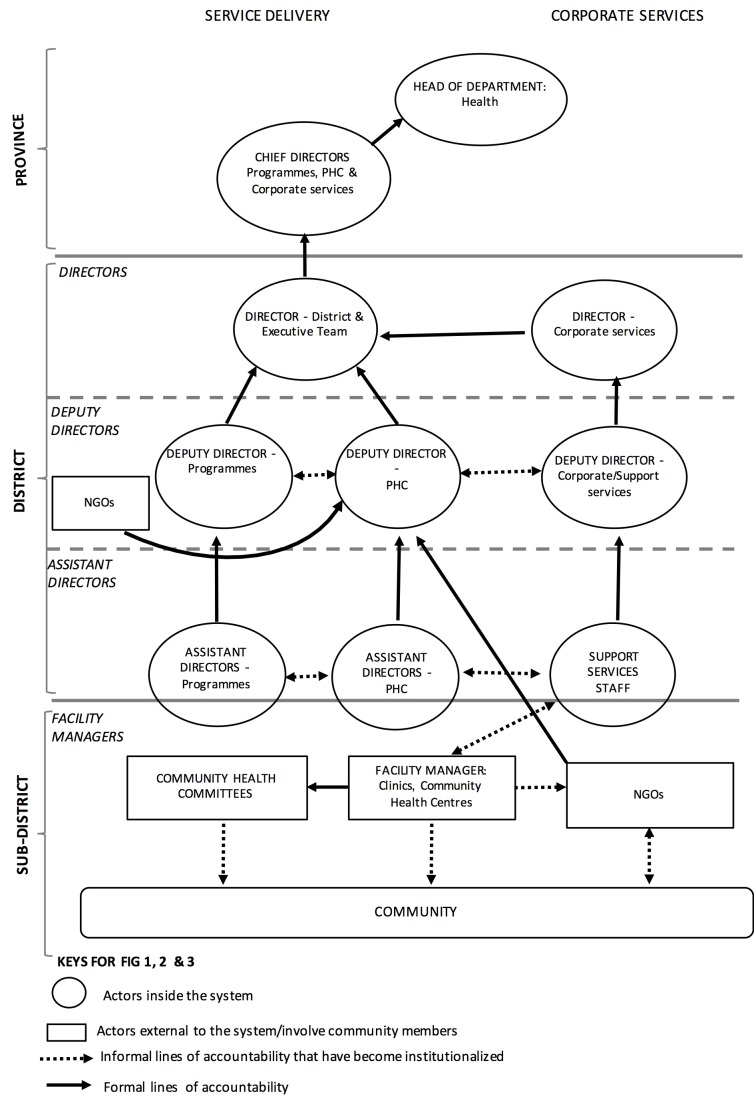

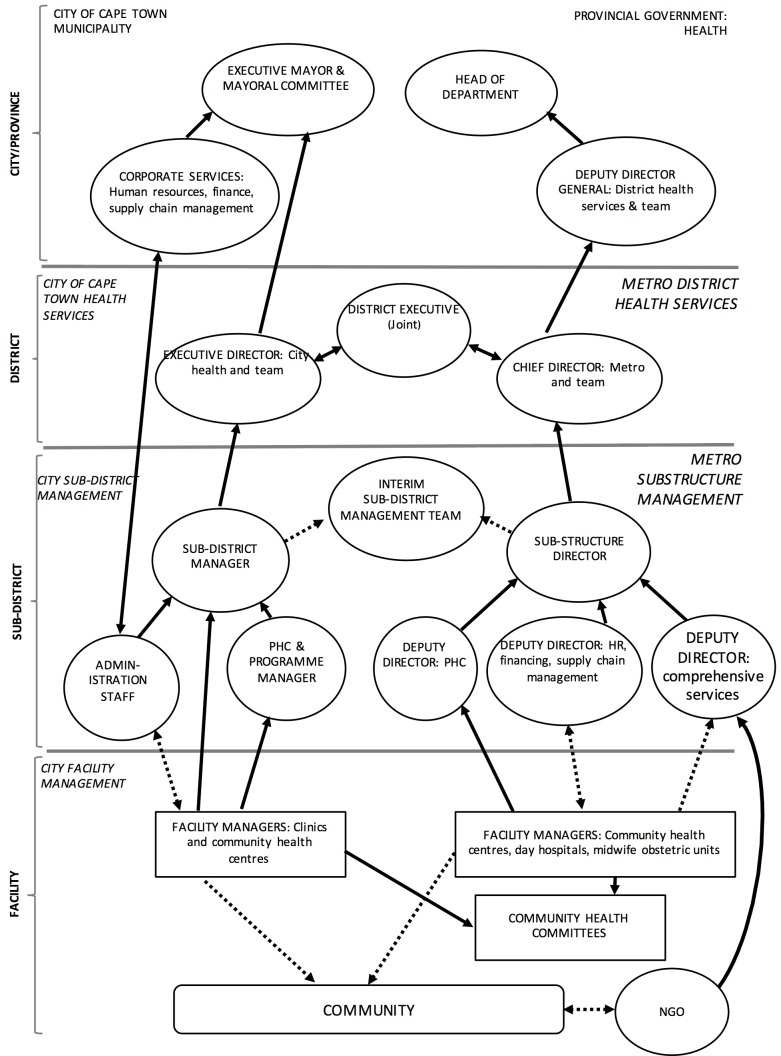

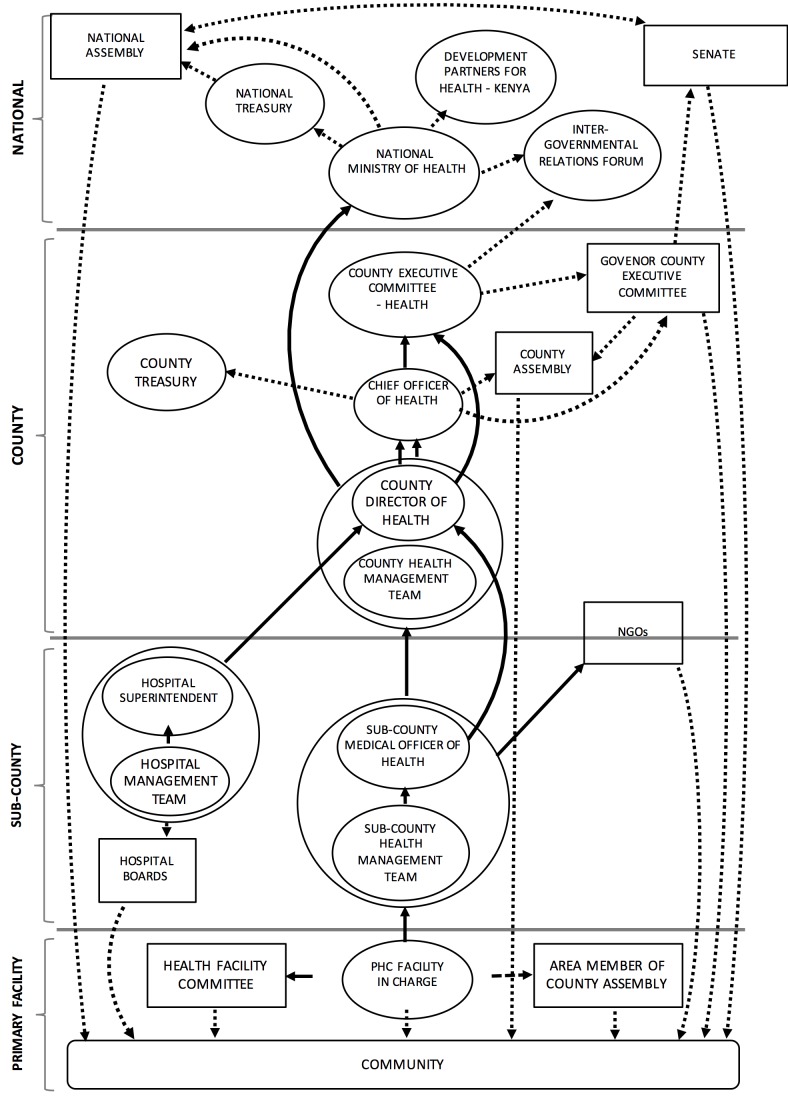

Three accountability maps (figures 1–3) were developed on the basis of discussions with health managers operating at the subnational levels of the health system about who they are answerable to and in what way. These maps include both formally agreed lines of accountability (in relation to line management and financial answerability, for example) but also, in some cases, more informal lines of accountability that had nonetheless become institutionalised at the time of our fieldwork.

Figure 1.

Accountability map of Sedibeng District, 2016. NGOs, non-governmental organisations; PHC, primary healthcare.

Figure 2.

Accountability map of the City of Cape Town/Metro District Health Services, 2013. HR, human resource; NGO, non-governmental organisation; PHC, primary healthcare.

Figure 3.

Accountability map of Kilifi County, 2017. NGO, non-governmental organisations; PHC, primary healthcare.

There are some common features across these maps.

First, they all reveal the multiple and multidirectional accountability demands that health managers face at all levels, including accountability upwards to managers, accountability across and down to colleagues and staff, and accountability outwards to facility users and the public.

Second, in all settings separate lines of responsibility have the potential to undermine service delivery in different ways. In South Africa there are different types of bureaucratic accountability in each site. In Sedibeng (figure 1), there are two lines of accountability—one for ‘Corporate Services’ (ie, all support services such as finance, information technology, supply chain, human resources and so on) and one for service delivery. This separation inevitably brings challenges in ensuring the synergy between functions needed to support service delivery, and may explain the emergence of more informal, but now quite fairly institutionalised forms of accountability among assistant directors in each line function. In Mitchells Plain, Cape Town (figure 2), there is accountability to both provincial and local government authorities for service delivery, and the interim subdistrict management team, an informal but now institutionalised forum, seeks to provide a venue for coordinating activities between these different authorities. In Kilifi (figure 3) there is a technical line of accountability of county health managers upwards to the national ministry of health and a separate political one up to the national senate through the county executive committee.

A third common feature of these maps is that they indicate a strong focus on formal internal accountability up the health and administration system hierarchies in each setting, as opposed to outwards to communities or the broader public. Box 1 above provides some examples of the kinds of mechanisms reported to enact the accountability lines in the maps, each of which involves a complex web of activities and responsibilities with an overall upwards focus. The way these mechanisms are enacted is largely bureaucratic in that there is a general orientation towards compliance to rules and targets as assessed through completion of forms and reports, as opposed to being more internalised and trust-based, as discussed in more detail below.

Finally, the fourth feature of these maps is that some informal forms of accountability have become relatively formalised or institutionalised and influence health managers. For example in Sedibeng, there are numerous interactions between the assistant directors of different departments such as PHC, programmes and administration, in which there are constant discussions about whether or not tasks and activities are being achieved, illustrating a form of peer accountability. In Kilifi, although facility managers are not formally and directly answerable to the new locally elected politicians—Members of the County Assembly (MCA)—some MCAs demand answerability from facility managers because they feel they have been given a mandate by the public to oversee government services including health facilities in their constituencies.

Bureaucratic accountability: laudable intentions and unintended consequences

As noted above, the accountability maps and discussions highlight the dominance of internal, bureaucratic processes, including those listed in box 1. Many of these mechanisms have laudable goals, with potentially important positive implications for healthcare provision and ultimately public health. However we often observed in learning site day-to-day routines that in practice these mechanisms can be demanding in time and energy and distracting from other activities and priorities. This can have negative implications for staff motivation, health delivery and ultimately public health.

An example of the laudable goals but practical realities of internal bureaucratic accountability processes is target setting in Cape Town. As described by Gilson et al18, annual targets have been set up in South Africa as one of a set of accountability mechanisms to track progress towards strategic plans, including to improve PHC services. As shown in vignette 1, they were perceived as very positive by senior managers, but very differently by front-line managers who found them disempowering and demotivating. Rather than recognising the value of the target setting processes, the PHC facility managers in Cape Town were therefore observed to merely comply with the reporting tasks, applying little effort towards wider improvements in PHC services,18 limiting the intended benefits of the targets.

Vignette 1.

The targets—for example, tuberculosis cure rates, immunisation coverage, service provision targets—are backed up by regular monitoring through ‘plan, do, review’ meetings where managers at different levels come together to examine facility, subdistrict and district performance against targets, identify challenges, and develop actions to address them. Gilson et al 18 reported that mid and senior health managers saw these processes as providing the following:

Standardised frameworks to guide lower level managers and, more specifically providers, to work differently to better meet population health needs.

A stable structure within which people know what is expected of them.

Direction towards common goals and providing people with a motivating force.

Taking this perspective, Gilson et al 18 argued that reaching a target can be seen to bring a sense of achievement and positive energy. However primary healthcare facility managers and staff talked very differently and much more negatively about targets. They generally describe them as disempowering, as some form of disciplinary tool, and as encouraging or enabling micromanagement by higher level managers. As the authors noted18:

Perhaps refracted through the prism of history and wider organizational culture, facility managers seem to understand the word ‘targets’ as authoritarian and therefore illegitimate (Gilson et al,18): “It’s all that is bad in the system…it also says ‘we don’t have agency’…‘we are bombarded, can’t do anything else’, so it removes accountability and responsibility for anything other than the target” and so “a lot of the target conversation is completely disembodied, it’s removed from the actual meeting of service needs”. (Research meeting notes—5 December 2012 from Gilson et al,18)

Responding to similar top-down accountability processes, facility incharges in Kilifi are typically required to both manage their facilities and provide services. They complete an array of monthly reports submitted to line managers to support planning, monitor performance and workload, and facilitate oversight of resources. Although facility managers felt these processes were important to enable resource allocation, and plan supportive supervision, mentorship and coaching, they also complained about the amount of paper-filling and reporting (table 1 12) that they have to do, variously describing it as ‘overwhelming’, ‘repetitious’, ‘confusing’, ‘tedious’ and ‘distracting’ from clinical care. There was also little direct positive feedback from these exercises, but rather concerns about being blamed and penalised for any mistakes. As noted by Nyikuri et al 12:

Table 1.

Financial reporting tools and processes12

| Clinical forms to show performance | Financial manuals and forms | |

| MOH711: TB control data. | Guidelines and reference documents. | Receipt vouchers (F017). |

| MOH711A: Integrated RH, HIV/AIDS, malaria, TB and nutrition. | Managing HSSF, an operations manual. | Payment vouchers (F021). |

| MOH113: Nutrition monthly reporting. | Guidelines on financial management for HSSF. | Travel imprest form (F022). |

| MOH717: Service workload. | Chart on accounts. | Local purchase orders. |

| MOH718: Inpatient morbidity and mortality. | Registers and books to be completed. | Local service orders. |

| MOH729AF: CDRR for ARV and OI medicine. | Memorandum vote book. | Request for quotations. |

| MOH730: Facility monthly ARV patient. | Receipt book. | Stock cards for all items in stores. |

| MOH731: Comprehensive HIV/AIDS facility reporting form. | Facility service register. | Imprest warrants. |

| MOH733B: Nutrition services summary tool. | Cash book. | Bank reconciliation forms (F030). |

| MOH734F: CDRR HIV nutrition commodity. | Cheque book. | Counter requisition and issue vouchers (S11). |

| MOH105: Service delivery report. | Cheque book register. | Counter receipt vouchers (S13). |

| MOH515: Chew summary. | Fixed asset register. | Handover forms. |

| MOH710: Vaccines and immunisation. | Imprest register. | Monthly financial report forms. |

| Consumables stock register. | Monthly expenditure report forms. | |

| Store register. | Quarterly financial report forms. | |

| Receipt book register. | Other items register. | |

| Forms/vouchers. | ||

ARV, antiretrovirals; CDRR, Consumption Data Report & Request; HSSF, Health Sector Services Fund; MOH, Ministry of Health; RH, reproductive health; OI, Opportunistic Infection; TB, tuberculosis.

Reporting challenges are largely with upward accountability, with financial reports in particular considered difficult and worrying given that in-charges can be held formally responsible for any anomalies…

In Kilifi, facility incharges’ concerns about accountability responsibilities are in a context of significant resource constraints, remuneration anxieties and lack of preparedness to conduct their managerial roles. Where accountability requirements unnecessarily detract from clinical care through, for example, duplication of forms, or gathered data never actually being used by those demanding it, they potentially undermine the very services they are designed to support.

Sedibeng showed a similar experience of some potentially valuable accountability mechanisms being implemented in such a way as to undermine the intention of the mechanism. Researchers observed, for example, that supervision processes had become so orientated around ensuring that facilities comply with stringent National Core Standards that there was little support offered to those being supervised. To illustrate, a manager reported that a detailed manual they used had reduced supervision visits to going through a lengthy checklist of requirements:

The supervisory manual is actually limited to being compliant to the core standards. There’s just a dashboard of indicators…elements that you are looking to help the clinic to get to this compliance. There are 196 elements that you need to assess and it is not just to say, yes it was not there. You have to interrogate; what is the element, is it really according to the documents? So a supervisory visit takes up to six to eight hours. It consumes a lot of time. (Sedibeng interview, Mid-level manager 1, 2014)

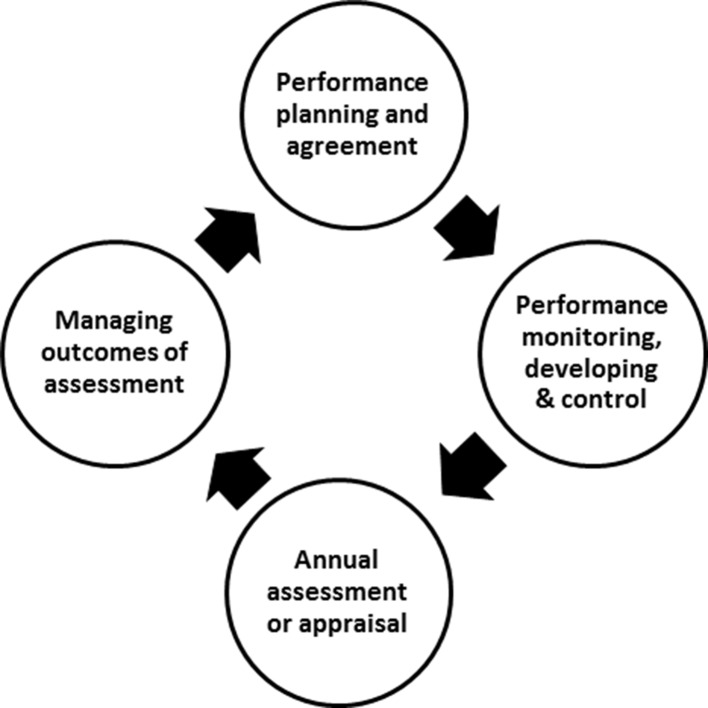

Another example of the laudable goals but practical realities of internal bureaucratic accountability processes is the implementation of the Performance Management and Development System (PMDS) in Sedibeng. A PMDS (figure 4) is aimed at ensuring that all government employees develop the skills and implement the activities required to achieve the health system’s goals. It involves a 12-month cycle over which performance is collaboratively planned, executed and assessed between employer and employee. The final of four steps involves the employer and supervisor reviewing performance, agreeing a final score rating, and discussing career incidences such as pay progression and performance awards. The score rating ranges from 1 (unacceptable) to 5 (outstanding), with 5 indicating the employee far exceeds the expected standards for the job and qualifies for an award.

Figure 4.

Performance Management and Development System cycle.

The PMDS should ensure supportive interaction between the supervisor and the employees throughout the cycle, including allowing both parties to ‘identify and provide the support needed’ and to ‘ensure continuous learning and development’.19 However Sedibeng managers’ comments of how this performance management tool is implemented illustrate how formulaic it has become:

Our performance management and development system is not aligned to operational plans…so outputs on PMDS are very vague. For some jobs there aren’t specific measurable goals, the items are too general. It has also become something that people comply to…they just change the dates. (Sedibeng interview, Senior manager 11, 2015)

…the system has now been designed that you get a score from 2 to 4. To avoid fighting [between manager and subordinates] people just give people a 4. It is a system that doesn’t work. (Senior manager and research team reflective meeting notes, 4 August 2015)

The latter quote illustrates the observation that managers give out scores regardless of merit in order to avoid contestation and maintain relationships.

Enabling bureaucratic accountability through emphasis on relational elements

In the previous section we showed that accountability mechanisms have good intentions and are often designed to include relational/interpersonal elements—for example, feedback meetings and opportunities for discussion and reflection. In practice, these good intentions can be undermined by implementation realities which reduce these processes to tick-box-style, routinised, depersonalised activities. In addition these realities appear to be aimed more at maintaining the status quo than at building relationships and transforming practice. Nevertheless, there are examples from each site and across all of the processes listed in box 1 of managers emphasising relational elements to enable internal accountability processes.

In Cape Town, for example, managers who were concerned about the didactic way that performance development meetings were implemented began to create new spaces for discussion on achievements, challenges and priorities between facility and subdistrict managers. These new meeting spaces became opportunities for team building and for creating new alternative forms of accountability where “it’s not [just] about holding people accountable, but providing a space to be supportive in holding them accountable” (Researcher field notes, 6 June 2012).18

In Kilifi, it was clear how crucial the interpersonal elements of supervisory processes are. In this context, facility incharges reported the potential to feel forgotten and isolated in dealing with significant resource constraints and other work-related challenges in what can be physically very distant facilities. A subcounty health manager mentioned that she encourages the incharges being posted to new facilities to contact her if they have any problems rather than to ‘go and die suffering alone’. Another male subcounty manager described monthly supervision visits to facilities as an important opportunity:

…to interact with the facility staff, so that you can identify with them any problems and possibly support them to see that they don’t continue suffering. Otherwise, others may be very discouraged; others may be very demoralized to remain in the facilities if nobody ever goes to say hi to them. But if you go there, you chat with them. If possible you take a drink with them. They feel I’m not wasted; I’m not alone… 12

Such visits, when they happen, are highly appreciated by the incharges with the importance of the relational elements of supervisory visits apparently recognised by managers. Aware that these monthly visits often do not happen because of resource challenges at the subcounty level, managers introduced—as an additional interaction point—monthly meetings in the county headquarters for all facility incharges. These meetings involve sharing of information, tracking of progress, and discussing problems and solutions among peers, as well as the deliberate inclusion of examples of good practice from some facilities to inspire others. The meetings allow communication of new developments in the region and feedback to everybody on issues raised in more individualised supervision meetings. As with the supervisory visits to facilities, the relational elements of these monthly meetings are highly valued by facility incharges.

Creatively using bureaucratic accountability mechanisms to challenge rules imposed from above

Beyond observing front-line managers enabling bureaucratic accountability through emphasising relational elements and positive feedback processes, we also observed managers exercising their agency to actively work across their accountability responsibilities and relationships to ensure continued provision of services. We noted the creative use of one set of accountability relationships (eg, to line managers or to community representatives) being drawn on to challenge another, in such a way that supported those managers to achieve their goals. In some cases this creativity is seen in actions that may seem relatively small and insignificant, but which can be critical in facilitating health facility functioning, especially when considering many such actions being implemented at different levels of the system. In other cases the creativity is relatively dramatic, with important widespread implications. Negotiations can become quite complex, drawing in a range of actors and requiring significant interpersonal skills.

An example of an arguably small action with important implications was a manager in Sedibeng transgressing a procurement rule to ensure his responsibility to patients (to have food) was met (vignette 2). What can be observed in this example is the way in which a manager appealed to his own and the wide systems’ accountability responsibility to the public to support his actions, for which he was potentially sanctionable.

Vignette 2.

In the district, there are a range of accountability requirements for procurement, including the need to request for purchases to the Basic Expenditure Committee (BEC) and to work under time-bound contracts with regular suppliers. Managers cannot purchase an item without a prior agreement and a contract as that would be a violation of the formal procurement process. A contract expired with a bakery and had not been renewed, but the manager decided to continue accepting bread from the bakery to feed patients in the maternity ward, many of whom stay for several days:

So the bakery will continue delivering…because in the district we cannot say that the contract has ended, therefore we will not accept bread, because we have patients that need the bread. We accept the bread knowing exactly that this was done without a purchase order number. Remember, services rendered without a purchase order is a violation; it constitutes irregular and wasteful expenditure. This is where one has to be bold…Do patients suffer without food in the district or do I have to put my head on the block? (Sedibeng interview, Senior manager 6, 2014)

This manager was clearly torn between his responsibilities to the patients versus following due process, as he is accountable to two different constituencies. There is a formal process in place to explain such a violation: a submission is made to the BEC, headed by a senior officer of finance and a senior officer of supply chain. If the explanation is considered justified and reasonable, then no action is taken against the individual. However it takes a committed and confident manager to resort to such a process:

So when BEC has looked at the repercussion, if they feel that I was saving the department because we were going to be on the first page of the newspaper, then they would approve. But in other cases, when they feel that you had time to follow the correct procedure and you did not, and instead ended up acting as though it was an emergency, they say corrective measures have to be taken on the Officer…you would be given a written warning. So they give some form of punishment. (Sedibeng interview, Senior manager 6, 2014)

In Kilifi we observed a relatively dramatic case of creative use of accountability mechanisms, with important widespread implications (vignette 3). In this case a subcounty manager who had worked in the region for several decades used two formal accountability mechanisms—an external accountability mechanism of a health facility committee with elected community representation, and a facility incharges’ answerability to that subcounty manager—to challenge the intended implementation by a new more senior county health manager of a top-down mandate (to remove user fees). Although the challenges of user fees are widely recognised locally and internationally, suddenly removing them without adequate planning and alternative sources of income can cause major challenges for service delivery. This was a concern for providers across the county. The subcounty manager was able to draw on formal accountability responsibilities, long-term relationships and an indepth institutional knowledge gained over time to temporarily continue the charging of user fees and achieve the objective of keeping services open during a time of crisis, an important achievement at least in the short term not only for the facility where the challenge was initiated, but across the entire county. As with the Sedibeng example, we see managerial agency, where a relatively empowered individual manages upwards, and in this case also outwards to community members, in order to achieve service delivery.

Vignette 3.

On 1 June 2013, the President of Kenya announced the removal of user fees and maternity fees from primary health facilities. The Government was going to compensate the facilities through direct funding to their bank accounts. However, 4 months down the line, no funds had been transferred to facilities, leading to a cash crisis—casual workers and utility bills went unpaid, and outreaches could not be conducted. In the face of water and electricity disconnection, filthy facilities (with casual staff leaving) and imminent closure, one facility incharge turned to her facility committee for a solution. Together with her committee they agreed to reintroduce user fees until the Government released the promised money. On learning of this development from Members of the County Assembly, a senior county manager sought to know under whose power the incharge had acted against a Presidential directive. This incident prompted a visit to the facility by a very high-level county team, without informing or inviting subcounty-level managers (previously and possibly still the direct supervisors of the facility incharges). The facility committee stood their ground and supported the incharge, and managed to convince senior county managers that services could not stall because of central government delays in funding. This innovation by one facility in charge with her committee became an official temporary solution for the whole county.

Source: Researchers reflective meeting 25_10_2013.

Discussion

In this paper we have drawn on long-term, primarily qualitative research conducted in three different district health system settings in Kenya and South Africa to present evidence of the micropractices of accountability among front-line managers at the subnational level. Here we discuss our three key findings in turn, relating them to the wider literature. In discussing each, we refer back to Hupe and Hill’s16 distinction between more public-administrative and more professional-participatory forms of accountability, and in particular highlight the importance in practice of coproduction as a mode of implementation across both. Coproduction implies interpersonal interaction and collaboration between professionals and between professionals and others (community members, researchers) to achieve individual and system goals. It can be used to describe the relational or interpersonal elements that we observed are built into the design of many bureaucratic accountability mechanisms but that are often lost in implementation practice, with negative implications for staff motivation, service delivery and ultimately public health. Relatedly, our experiences show the importance of managerial agency in working with multiple accountability lines, suggesting that approaches need to be found to recognise, value and even enable this agency where it is used to support health system goals.

Front-line managers operate in a web of accountability responsibilities and demands

We have shown that front-line managers working in facilities and at subnational levels operate in a complex web of accountability demands. They are answerable to a range of different actors in different directions and in ways that can conflict with each other. This observation has been made by others from across a wide range of disciplines. Hupe and Hill,16 for example, talked about ‘street-level bureaucrats’ in public policy being:

… held accountable in different ways and to varying degrees…Within the web of these multiple accountabilities which produce possibly contradictory action imperatives, street-level bureaucrats constantly weigh how to act (p296).

We showed potential conflicting lines of accountability among the Kilifi facility managers, for example, who were concerned that meeting their upward accountability demands (form filling) was distracting them from their clinical duties. This pattern and concern has been noted elsewhere in Kenyan health centres and dispensaries,20 and in other settings.21–23 In India, for example, Fochsen et al 21 noted that tuberculosis doctors working in organisations perceived as inefficient and resource-constrained faced a dilemma of how to balance meeting the obligations of the directly observed treatment, short-course programme with what were often quite different needs and expectations of patients. Similar accountability tensions within hierarchical health systems are highlighted elsewhere. For instance centralised decision-making processes in Ghana24 reduced capacity for district-level responsiveness to the implementation of policies. In India,9 as much as bureaucratic accountability mechanisms took place through a top-down mode, front-line workers managed the conflicting accountability relationships through informal negotiations. Consequently, this altered formal mechanisms in ways that sometimes compromised service delivery.9

Where accountability responsibilities conflict, front-line managers have to make choices. As well as noting that accountability upwards to line managers often ‘wins’, because those managers and others higher up the system have the potential to enact sanctions, we also observed in both South Africa and Kenya that some managers take significant risks in an effort to meet the needs of patients and the public (eg, confronting senior staff or going against rules). Actions that challenge health system hierarchies and system policies require confidence and commitment, and in some cases careful negotiation across a wide range of actors. Drawing also on Cleary et al,17 the choices that managers make in such situations of conflict, and their implications for service delivery, are likely to be centrally influenced by the attitudes, perceptions, values and beliefs of all of those potentially involved. Understanding and working to align potentially diverse positions require creativity and agency among front-line managers, and interaction and collaboration with others. These forms of coproduction are likely to be influenced by the resources available to managers (personnel, funds and so on) as well as their capabilities (technical and interpersonal).

Do front-line managers' and others’ creative accountability actions have wider and longer term implications for the resilience of health systems in the face of the routine, multiple challenges they face? This is influenced by if and how the new ideas or ways of working become embedded over time in relationships and managerial routines.14 Where new relationships and managerial routines are observed, further analysis is required to examine whether these indicate or nurture resilience (where organisational functioning is strengthened) or ‘maladapted emergence’ (where organisational practices are undesirable or unsustainable). Our analysis presented elsewhere14 is that the reintroduction of user fees in Kilifi to cope with funding shortfalls, despite a prior policy decision to remove them because they reduce access for the poorest, is an example of maladapted emergence, whereas the introduction of regular meetings for all PHC incharges is an illustration of organisational strengthening.

Accountability processes are often shaped by audit-style, bureaucratic mechanisms

While recognising their multidirectional and conflictual nature, our findings indicate that many accountability responsibilities do nevertheless operate vertically—linking front-line providers to the state through bureaucratic accountability mechanisms. As noted in the background, audit-style bureaucratic accountability requirements are relatively detailed, standardised and centralised approaches to accountability. Efforts to ensure that healthcare services are efficient, effective and equitable, and a recognition that front-line managers have the potential to exercise discretion in policy implementation, have led to the emergence of a global culture where authorities are constantly introducing ‘more rules, tighter control, and stricter procedures’.16 We found that such mechanisms, although often well intended, are often reduced in practice to tick-box-style, routinised, depersonalised activities aimed more at maintaining the status quo than at building relationships and transforming practice. Front-line managers in Cape Town, for instance, found the annual target setting and reviewing processes to be authoritarian micromanagement, with much of the conversation ‘completely disembodied [and] removed from the actual meeting of service needs’ (Research meeting notes—5 December,18 p7). In Kenya submitting monthly reports often required considerable effort and time, despite recognition of duplication and inadequacies across forms. Similar findings have been documented elsewhere. In India, for example, health workers expressed dissatisfaction with targets:Every month, it is the same meeting, the same subjects, same reports and same faces and are rigidly focused on targets as opposed to quality of work; ’All they are interested in is whether you fill in the reports and comply with targets…They are not interested in the work we do' (p 211).9

Thus our research offers some support to the idea that there is an emerging ‘audit society’ in which achieving organisational legitimacy is prioritised over and potentially even undermines efficiency and quality, and where the day-to-day operations of officials are monitored and regulated through ‘ritualized practices’.23 25 Given typical power differentials between the accountee and the accountor, a relationship of upward accountability is created, in which organisational culture of constant reference to and dependence on central authorities is perpetuated.26 We observed this general upwards pattern and emphasis of bureaucratic accountability in Kenya and South Africa, even in the context of devolution in Kenya. In fact regarding the latter, we have shown elsewhere that there has even been a form of ‘re-centralization’ under devolution, where previous authority at the hospital level has been transferred to higher up the system at the county level.27

We noted in the previous section the importance of creativity and agency among front-line managers, and of interaction and collaboration with others—or coproduction—in making sure that accountability responsibilities to patients and the public are met in the face of competing accountability upwards. Achallenge with some of the implementation realities of bureaucratic accountability mechanisms is that they can in fact crowd out relational/interpersonal elements, as well as stifle the local-level innovations and resilience that can be vital to improving responsiveness to communities and healthcare services.17 That agency is removed or stifled is illustrated in the Cape Town managers’ comments that “we don’t have agency”…“we can’t do anything else”. As others have noted, the reduction of performance review to the measurement of staff to meet targets undermines broader health system goals that are more difficult to measure or attribute to specific actors’ responsibilities.28 The undermining of agency and self-determination also potentially undermines the intrinsic motivation of staff, a vital aspect in maintaining and sustaining health services and the health system.29 It has been documented elsewhere that an external motivation (like a target being reviewed) can undermine the motivation from within (such as an intrinsic sense of duty or responsibility) through removing a sense of responsibility in the person: ‘the actor feels that rather than themselves, the person undertaking the external intervention is responsible’.30

Further unintended consequences of bureaucratic accountability mechanisms that encourage compliance are their potential manipulation—what has been called ‘gaming’. Involving the falsifying of data or adjusting the interpretation of the data to suggest improvement; a phenomenon linked to control measures of performance.31 We observed an example of this in Sedibeng in performance appraisal cycles. In other settings it has been particularly observed in relation to performance-based pay (where there is clear motivation for gaming) but also in more routine health worker activities. For example, in the implementation of a surgical safety checklist in an African university hospital, nurses sometimes ticked the checklist without following the formal procedure, as a way of challenging top-down prescriptions, and also because of the work pressures and staff shortages.32

Overall, our findings regarding bureaucratic accountability processes are that many have laudable goals, with potentially important positive implications for healthcare and public health. However mechanisms can be poorly designed, resourced or implemented, and may be overdemanding, introduce anxiety and resistance, or clash with existing ideas of ‘good practice’. Thus the laudable intentions can fail, with damaging implications for staff, health delivery and ultimately public health. Regarding performance reviews specifically, our findings resonate with Barrett’s33 assertion that top-down pressures can reduce performance to conformance.33

Relationships matter

Our findings illustrate how some managers gravitate towards more relational processes of accountability. We saw this in a Kilifi subdistrict manager’s response to the introduction of user fees (vignette 3) and in the Sedibeng manager’s efforts to ensure patients were fed (vignette 2). In Cape Town to alleviate the negative consequences of the performance evaluation, the ‘plan, do, review’ meetings between the subdistrict managers and the PHC facility managers introduced negotiation and collaborative goal-setting to support shared outcomes, and in Kilifi similar elements were introduced to supervision meetings. This pattern of introducing and emphasising relational elements has also been observed elsewhere. In India, for example, Programme Officers indicated how informal relationships were necessary to generate ‘respective and responsive team effort’.9 Some meetings were revised to encourage provision of feedback, comments and complaints from staff, and collective exchange across staff so that there was shared understanding of particular practices.9

These findings suggest that for the good intentions of bureaucratic accountability mechanisms to be met, relational/interpersonal elements—or coproduction—are essential and should be recognised, valued and even supported. This has been successfully tried in Rwanda, where a ‘hands-off’ approach was used in a performance-based financing initiative. Implementers were able to enhance autonomy and promote an innovative spirit among health providers through allowing them to collaboratively develop their own shared goals and agree together on ways to achieve targets.34 Our work would suggest the need for more such initiatives. Nevertheless, recognising as noted above how important culture and attitude are for the implementation of accountability mechanisms,17 such initiatives need to be carefully codesigned with the range of key actors who have a deep understanding of the context and of potential perverse outcomes. Furthermore, the potential for perverse outcomes and the implications of initiatives for everyday resilience of health systems need to be carefully considered and tracked.

Conclusion

Our examination of the micropractices of accountability operating at the subcounty or subdistrict level across three learning sites shows the multiple directions and forms of accountability operating at these levels, and the dominance and unintended consequences of bureaucratic forms of accountability. We have highlighted the importance of relational elements in enabling positive goals of bureaucratic accountability and have shown how one set of accountability requirements can be creatively drawn on to challenge another. We have demonstrated the importance in these interpersonal processes of coproduction between professionals and between professionals and others (community members, researchers). Our analysis suggests that policies and interventions supportive of positive interpersonal interactions and that build coproduction are essential to target-based and/or audit-style mechanisms achieving their positive intended effects. This includes promoting initiatives that recognise value and enable agency of leaders across the health system in ways that build everyday resilience and minimise the potential for maladaptation.

Acknowledgments

The research participants in the learning site are acknowledged. Acknowledgement is especially extended to Shakira Choonara, Mary Nyikuri and Salamina Hlahane and the larger RESYST Health Systems Governance theme members for their support. The development of this paper was facilitated by discussions that took place at a writing workshop in April 2016 organised by the Consortium for Health Systems Innovation and Analysis (CHESAI) to generate indepth, Southern-led understandings and perspectives on health systems and governance. The CHESAI is funded by a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Canada.

Footnotes

More specifically we have worked in one geographical area in which health services are managed by two different health authorities. The area is the Mitchells Plain subdistrict of the City of Cape Town, a local government authority, which falls within the Mitchells Plain/Klipfontein substructure, one of four within the provincial government’s Metro District Health System.

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: All authors were involved in conceptualising this paper and in conducting the analyses. NN, SM and LG were responsible for initiating the drafting and revisions of this paper. NN, SM, LG, JG, SC, EB and BT read and commented on successive paper drafts. NN, SM and LG were involved in the revisions of the final draft. All authors were also involved in the underlying data collection and analysis processes in the different learning sites. NN, SM and LG read and approved the final manuscript. NN and JG work together. SM, EB and BT work together. LG and SC work together. The work that provided the foundation for this paper is continuing; data already collected remain available to the researchers only.

Funding: This research is an output from the Resilient and Responsive Health Systems (RESYST) Consortium funded by the UK Aid from the Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of low-income/middle-income countries.

Disclaimer: The views expressed and information contained in this article are not necessarily those of or endorsed by the DFID, which can accept no responsibility for such views or information or for any reliance placed on them.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) (LSHTM ethics ref: 6542), the University of the Witwatersrand’s Human Research Ethics Committee (clearance certificate no M131136), Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) (ref: SERU 2205), and the University of Cape Town (UCT) (HREC ref 039/2010). Signed consent was obtained for all interviews conducted.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Author note: NN, LG, JG, BT, SC, EB and SM are members of the Resilient and Responsive Health Systems (RESYST) Consortium.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2006. Working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Standing H. Understanding the ’demand side' in service delivery: definitions, frameworks and tools from the health sector. London: DFID Health Systems Resource Centre, Department for International Development, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brinkerhoff DW. Accountability and health systems: toward conceptual clarity and policy relevance. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:371–9. 10.1093/heapol/czh052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mills A. Decentralization and accountability in the health sector from an international perspective: what are the choices? Public Administration and Development 1994;14:281–92. 10.1002/pad.4230140305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Byrkjeflot H, Christensen T, Laegreid P. The Many Faces of Accountability: Comparing Reforms in Welfare, Hospitals and Migration. Scan Polit Stud 2014;37:171–95. 10.1111/1467-9477.12019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bossert TJ, Beauvais JC. Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: a comparative analysis of decision space. Health Policy Plan 2002;17:14–31. 10.1093/heapol/17.1.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strathern M. Audit Cultures: Anthropological studies in accountability, ethics and the academy. London and New York: Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dixon-Woods M, Leslie M, Bion J, et al. . What counts? An ethnographic study of infection data reported to a patient safety program. Milbank Q 2012;90:548–91. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00674.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. George A. ’By papers and pens, you can only do so much': views about accountability and human resource management from Indian government health administrators and workers. Int J Health Plann Manage 2009;24:205–24. 10.1002/hpm.986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGivern G, Fischer MD. Reactivity and reactions to regulatory transparency in medicine, psychotherapy and counselling. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:289–96. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Le Grand J. Motivation, agency and public policy: of knight and knaves, pawns and queens. Oxford University: Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nyikuri M, Tsofa B, Barasa E, et al. . Crises and Resilience at the Frontline-Public Health Facility Managers under Devolution in a Sub-County on the Kenyan Coast. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144768 10.1371/journal.pone.0144768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilson L, Lehmann U, Schneider H. Practicing governance towards equity in health systems: LMIC perspectives and experience. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:171 10.1186/s12939-017-0665-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilson L, Barasa E, Nxumalo N, et al. . Everyday resilience in district health systems: emerging insights from the front lines in Kenya and South Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000224 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lehmann U, Gilson L. Action learning for health system governance: the reward and challenge of co-production. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:957–63. 10.1093/heapol/czu097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hupe P, Hill M. Street-level bureaucracy and public accountability. Public Adm 2007;85:279–99. 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00650.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cleary SM, Molyneux S, Gilson L. Resources, attitudes and culture: an understanding of the factors that influence the functioning of accountability mechanisms in primary health care settings. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:320 10.1186/1472-6963-13-320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilson L, Elloker S, Olckers P, et al. . Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: South African examples of a leadership of sensemaking for primary health care. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:30 10.1186/1478-4505-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Department of Public Service and Administration. Employee Performance Management and Development System. Department of Public Service and Administration. Pretoria: Republic of South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waweru E, Goodman C, Kedenge S, et al. . Tracking implementation and (un)intended consequences: a process evaluation of an innovative peripheral health facility financing mechanism in Kenya. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:137–47. 10.1093/heapol/czv030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fochsen G, Deshpande K, Ringsberg KC, et al. . Conflicting accountabilities: Doctor’s dilemma in TB control in rural India. Health Policy 2009;89:160–7. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kluvers R, Tippett J. Mechanisms of Accountability in Local Government: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Business and Management 2010;5:46–53. 10.5539/ijbm.v5n7p46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McGivern G, Ferlie E. Playing tick-box games: Interrelating defences in professional appraisal. Human Relations 2007;60:1361–85. 10.1177/0018726707082851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwamie A. Balancing Management and Leadership in Complex Health Systems Comment on "Management Matters: A Leverage Point for Health Systems Strengthening in Global Health". Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:849–51. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Power MK. The Audit Society: Rituals of Verification. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yilmaz S, Beris Y, Serrano-Berthet R. Linking Local Government Discretion and Accountability in Decentralisation. Development Policy Review 2010;28:259–93. 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00484.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barasa EW, Manyara AM, Molyneux S, et al. . Recentralization within decentralization: County hospital autonomy under devolution in Kenya. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182440 10.1371/journal.pone.0182440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eldridge C, Palmer N. Performance-based payment: some reflections on the discourse, evidence and unanswered questions. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:160–6. 10.1093/heapol/czp002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frey BS, Jegen R. Motivation Crowding Theory. Journal of Economic Surveys 2001;15:589–611. 10.1111/1467-6419.00150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paul F. Health Worker Motivation and the Role of Performance Based Finance Systems in Africa: A Qualitative Study on Health Worker Motivation and the Rwandan Performance Based Finance Initiative in District Hospitals. London: Development Studies Institute. London School of Economics and Political Science, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kelman S, Friedman JN. Performance Improvement and Performance Dysfunction: An Empirical Examination of Distortionary Impacts of the Emergency Room Wait-Time Target in the English National Health Service. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2009;19:917–46. 10.1093/jopart/mun028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aveling EL, McCulloch P, Dixon-Woods M. A qualitative study comparing experiences of the surgical safety checklist in hospitals in high-income and low-income countries. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003039 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barrett SM. Implementation Studies: Time for a Revival? Personal reflections on 20 years of Implementation Studies. Public Adm 2004;82:249–62. 10.1111/j.0033-3298.2004.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soeters R, Habineza C, Peerenboom PB. Performance-based financing and changing the district health system: experience from Rwanda. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:884–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]