Abstract

The purpose of the study is to examine disparities in AET adherence and discontinuation among Texas Medicaid-insured early-stage breast cancer patients. Texas Cancer Registry Medicaid-linked database was used from 2000 to 2007 for breast cancer patients aged 20–64. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to test the association of race/ethnicity and geographic factors with AET adherence and discontinuation. Of the 1240 women with breast cancer, 60.8% of non-Hispanic white vs 46.6% of Black patients were adherent to AET in the first year. After adjusting for confounding, Black patients had lower odds of adherence compared to non-Hispanic white patients (Odds ratio 0.62, 95% CI 0.44–0.87), but they were not more likely to discontinue therapy during the study period. Patients from the Texas/Mexico border had higher odds of adherence compared to other regions (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.29–4.18). There are substantial racial and geographic disparities in AET adherence and discontinuation among Texas Medicaid-insured women.

Keywords: AET, Race/ethnicity, Discontinuation, Adherence, Medicaid

Introduction

Racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality have been reported to be attributed to factors such as late stage at diagnosis [1, 2], socioeconomic status [3], and the initiation and timing of effective recommended treatment for breast cancer [1, 3]. Timely receipt of nationally recommended treatment leads to substantial reduction in breast cancer mortality [4] and adherence to guidelines for systemic adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET), for example, is associated with improved disease-free survival for women with early-stage breast cancer [5–9]. It is estimated that treatment with Tamoxifen, a form of AET, can reduce 5-year mortality by up to 26% [5, 7, 10]. Previous studies have examined lower adherence to AET for non-white women, which may contribute to the disparities in breast cancer mortality observed between minorities and white women [11, 12].

AET treatment includes Tamoxifen and the aromatase inhibitors (AIs, including exemestane, anastrozole, and letrozole). The NCCN recommends that women with early breast cancer receive initial AET with tamoxifen if they are premenopausal at diagnosis or an aromatase inhibitor or tamoxifen if they are postmenopausal. In general, the drugs are typically prescribed every day for 5 years and may involve switching between medications due to complications and/or a change in menopausal status [13]. Understanding adherence and discontinuation during the first 12-months of treatment following breast cancer diagnosis can help identify specific subgroups or those at high risk of non-adherence for further intervention.

Despite the effectiveness of AET to improve survival and decrease cancer recurrence, between 55–75% of breast cancer patients are not adherent to AET during 1-year period [14] and the proportion of being not adherent is even higher for minority women [15, 16]. Previous studies have examined that black patients had 24% lower odds of adherence to AET compared to non-Hispanic white women [11]. Low adherence is associated with the number of other medications prescribed for comorbidities [17], demographic characteristics such as age [12, 18], and the side effects [14, 19–23]. However, little is known about the factors that influence adherence and discontinuation among a group of low-income and racially diverse patients on public insurance. Studies have shown that among the Medicare-insured population, racial/ethnic differences in adherence and discontinuation of AET exist despite comprehensive public insurance; however, they are limited to patients older than 65 years [24].

Because the known risk factors of adherence to AET, such as low socioeconomic status [11, 16], and being a minority [11, 16, 24], are predominately prevalent among the Medicaid population, studying these factors in this population is critical. Texas Medicaid provides comprehensive medical care to breast and cervical cancer patients, and mothers and children in low-income households [25]. The program provides free or low-cost medication to beneficiaries [25]. In Texas, the second most populous state in the U.S., approximately 7% of adults (age 19–64) are Medicaid enrollees [25]. Studies using TCR data have found that black and Hispanic patients diagnosed with breast cancer have a higher risk of mortality [26, 27] which may be due to later stage at diagnosis [27], low poverty [26, 27], and residential segregation [28]. No studies have examined AET treatment patterns by race/ethnicity which may further explain the racial/ethnic disparities in mortality. Further, Texans diagnosed with cancer are a population that is widely understudied relative to those in the SEER Cancer registries. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to identify if there are racial/ethnic and sociodemographic differences in (1) 1-year adherence to AET overall, and (2) AET discontinuation during the first year of treatment.

Methods

Database

Texas Cancer Registry (TCR) Medicaid-linked database was used to identify cancer patients from 2000 to 2007. The TCR database contains patient-level demographics, first course of treatment, and other tumor factors, which has been described in detail elsewhere [29]. Medicaid data contain medical claim files for medication use and medical procedures across inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy settings for patients enrolled in Texas Medicaid.

Study design and population

A total of 1240 women were included in this retrospective cohort study if they were diagnosed with a primary breast cancer at age 20–64 in 2000–2006 who filled a prescription for adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) within 1 year after diagnosis and were continuously enrolled in Medicaid for 12 consecutive months after the date of AET initiation. Our study only includes women who remained enrolled in Medicaid continuously. Therefore, those that died or who were no longer eligible for enrollment or moved away from Texas during the study period were excluded. Patients were excluded if they had distant stage tumors.

Study outcomes

Adherence of AET was defined by the medication possession ratio (MPR≥80%) for either tamoxifen at initiation or an AI at initiation (yes or no). AIs included anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole. To calculate the MPR, we analyzed the national drug code (NDC), date of service, and days’ supply of medication from Medicaid claims data. MPR was defined as the number of pills supplied over the 1-year period after the initiation of AET. A woman was considered to have initiated AET if the first evidence for a prescription fill for AET was within 12 months of the date of diagnosis. Patients were classified based on their initial AET drug type at initiation. Patients that switched AET medication during the study period were considered to have stopped taking any remaining drug on-hand and to have started the new drug on the first date of prescription fill for the new AET drug. Therefore, any remaining days’ supply for the initial drug was not counted in the medication possession ratio.

Discontinuation of AET was defined as a gap in medication supply of ≥ 90 days during the 1 year period after the date of initiation of AET. It was evaluated within several time periods: immediate discontinuation (discontinuation right after the first prescription), discontinuation within 3 months, between 3 and 6 months, and between 6 and 9 months after AET initiation.

Independent variables and covariates

Race/ethnicity was identified from Medicaid and categorized into four groups: White, Black, Hispanic, and Others. Age was grouped into three categories: 20–44, 45–54, or 55–64. Other patient covariates included tumor stage (Local/Regional), receipt of chemotherapy (Yes/No), radiation therapy (Yes/No), and surgery (Yes/No). Tumor stage was identified through TCR data and included localized tumor as local tumor stage, and those without distant metastasis as regional tumor stage. Treatment with breast cancer surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy was identified from both TCR and Medicaid claims data using procedure codes (ICD-9-CM) and Common Procedure Terminology codes defined elsewhere [30–33]. A modified version of the Charlson comorbidity index was used to assess the comorbid condition for breast cancer patients [34–36]. The index is based on the procedure and diagnosis codes (ICD-9-CM) from Medicaid claims record made between 6 months before and 3 months after breast cancer diagnosis. Year of diagnosis was grouped into two groups: 2000–2004 and 2005–2007.

Based on the 2000 US Census, we included variables categorized into tertiles based on the proportion of the county-level population living below the federal poverty level (≤ 16, 16.1–18.3, ≥ 18.4), county-level median income (≤$33,502, $33,503–$41,946, ≥$41,947), and the number of direct primary care (DPC) physicians per 100K population (≤ 103.9, 104–198.7, ≥ 198.8) in the county of residence. Region variables included whether the patient lived at the Texas–Mexico border (Yes/No). This variable was coded using 3-digit county Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) codes assigned by the US Census Bureau where the patient resided at the date of diagnosis. The FIPS codes were linked with the Center for Health Statistics Texas County Public Health and Health Service regions which classify county regions adjacent to the Texas–Mexico border. We also classified region based on whether patients resided in counties considered by the US Census Rural–Urban Continuum Codes to be Metro or non-Metro areas.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of patient demographics and sociodemographic characteristics across the racial/ethnic groups were analyzed first. The χ2 tests were used to assess whether there were significant differences among race/ethnicity and other variables, and were also used to examine the differences between adherence to AET (any AET at initiation, tamoxifen at initiation, and AI at initiation) and other variables. Three multiple logistic regressions were performed to analyze the relationship between 12-month AET adherence (yes or no) and patient characteristics to examine racial and geographic disparities for each group of patients based on the type of AET they filled a prescription for at initiation (any AET at initiation, tamoxifen at initiation, and AI at initiation). We also examined the association of medication discontinuation yes or no immediately after first prescription, at 3-months, 6-month, and 9-months) with other variables. Multiple collinearity tests were run between each of the independent variables and none were excluded because no variable had a Pearson’s correlation coefficient r > 0.7 or a variance inflation factor (VIF) > 7 in the final regression models. All P values are 2-sided and were considered significant at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

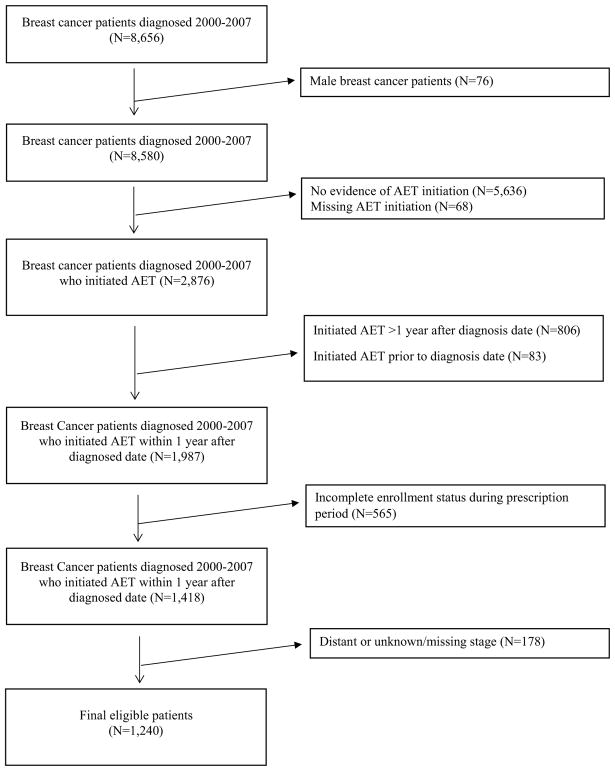

A total of 1240 Texas Medicaid-insured women with local or regional breast cancer met the selection criteria (Fig. 1). Of these, the largest racial/ethnic group was Hispanic which represented 39.4% of the study cohort, followed by non-Hispanic white (38.3%) and black (17.7%) (Table 1). The majority of patients were 50–64 years of age (60.8%). A larger proportion of Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic white patients lived in areas where ≥ 18.4% of the population lived below the federal poverty level (58.6% vs. 20.8%), received chemotherapy (67.2% vs 56.8%), and radiation (60.0% vs. 48.2%). Notably, a greater proportion of black, compared to white patients, lived in counties where there were ≥ 198.8 physicians per 100K persons (65.8% vs 39.8%) and metropolitan counties (84.5% vs 72.6%).

Fig. 1.

Study consort diagram

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics in Medicaid-insured women with breast cancer who received AET, by race/ethnicity

| White | Black | Hispanic | Total number | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| No. (col.%) | No. (col.%) | No. (col.%) | No. (col.%) | ||||||

| Age (years) | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| 20–34 | 10 | (2.1) | 12 | (5.5) | 28 | (5.7) | 51 | (4.1) | |

| 35–49 | 156 | (32.8) | 88 | (40.2) | 178 | (36.5) | 435 | (35.1) | |

| 50–64 | 309 | (65.1) | 119 | (54.3) | 282 | (57.8) | 754 | (60.8) | |

| Tumor stage | 0.19 | ||||||||

| Local | 259 | (54.5) | 116 | (53.0) | 235 | (48.2) | 643 | (51.9) | |

| Regional | 216 | (45.5) | 103 | (47.0) | 253 | (51.8) | 597 | (48.2) | |

| County-level poverty, % below FPL | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 16 | 218 | (45.9) | 89 | (40.6) | 79 | (16.2) | 408 | (32.9) | |

| 16.1–18.3 | 158 | (33.3) | 104 | (47.5) | 123 | (25.2) | 408 | (32.9) | |

| ≥ 18.4 | 99 | (20.8) | 26 | (11.9) | 286 | (58.6) | 424 | (34.2) | |

| County-level median Income | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 33,502 | 109 | (23.0) | 28 | (12.8) | 261 | (53.5) | 409 | (33.0) | |

| 33,503 – 41,946 | 175 | (36.8) | 83 | (37.9) | 126 | (25.8) | 400 | (32.3) | |

| ≥ 41,947 | 191 | (40.2) | 108 | (49.3) | 101 | (20.7) | 431 | (34.8) | |

| DPC physicians per 100K population | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 103.9 | 161 | (33.9) | 50 | (22.8) | 119 | (24.4) | 341 | (27.5) | |

| 104–198.7 | 125 | (26.3) | 25 | (11.4) | 205 | (42.0) | 372 | (30.0) | |

| ≥ 198.8 | 189 | (39.8) | 144 | (65.8) | 164 | (33.6) | 527 | (42.5) | |

| Region | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Metro | 345 | (72.6) | 185 | (84.5) | 416 | (85.3) | 998 | (80.5) | |

| Non-metro | 130 | (27.4) | 34 | (15.5) | 72 | (14.8) | 242 | (19.5) | |

| Year of diagnosis | < 0.05 | ||||||||

| 2000–2004 | 308 | (64.8) | 145 | (66.2) | 280 | (57.4) | 766 | (61.8) | |

| 2005–2007 | 167 | (35.2) | 74 | (33.8) | 208 | (42.6) | 474 | (38.2) | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| No | 205 | (43.2) | 81 | (37.0) | 160 | (32.8) | 470 | (37.9) | |

| Yes | 270 | (56.8) | 138 | (63.0) | 328 | (67.2) | 770 | (62.1) | |

| Radiation therapy | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| No | 246 | (51.8) | 119 | (54.3) | 195 | (40.0) | 596 | (48.1) | |

| Yes | 229 | (48.2) | 100 | (45.7) | 293 | (60.0) | 644 | (51.9) | |

| Surgery | 0.32 | ||||||||

| No | 28 | (5.9) | 18 | (8.2) | 23 | (4.7) | 73 | (5.9) | |

| Yes | 447 | (94.1) | 201 | (91.8) | 465 | (95.3) | 1167 | (94.1) | |

| Comorbidity scores | 0.12 | ||||||||

| 0 | 290 | (61.1) | 139 | (63.5) | 325 | (66.6) | 792 | (63.9) | |

| 1–2 | 128 | (27.0) | 46 | (21.0) | 103 | (21.1) | 286 | (23.1) | |

| ≥ 3 | 57 | (12.0) | 34 | (15.5) | 60 | (12.3) | 162 | (13.1) | |

| Total | 475 | (100.0) | 219 | (100.0) | 488 | (100.0) | 1240 | (100.0) | |

Of the 1240 patients who were followed for 12 months after the first prescription fill for AET medication (either tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor), 733 (59.1%) were adherent (MPR ≥ 80%) (Table 2). A greater proportion of patients that initiated with an AI were adherent compared to those that initiated with tamoxifen (64.3% vs 55.0%). Only 46.6% of black patients were adherent to AET during the study period compared to 60.8% of non-Hispanic white and 61.9% of Hispanic patients.

Table 2.

Percentage of patients in women with breast cancer adherence to AET, by AET type (N = 1240)

| Characteristics | Adherence to AET (N = 733) | P | Adherence who initiated Tamoxifen (N = 382) | P | Adherence who initiated AIs (N = 351) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |||||||

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | < 0.05 | 0.09 | ||||||

| 20–49 | 262 | (53.9) | 200 | (52.2) | 62 | (60.2) | |||

| 50–64 | 471 | (62.5) | 182 | (58.5) | 289 | (65.2) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | < 0.001 | 0.15 | < 0.05 | ||||||

| White | 289 | (60.8) | 140 | (56.5) | 149 | (65.6) | |||

| Black | 102 | (46.6) | 57 | (46.0) | 45 | (47.4) | |||

| Hispanic | 302 | (61.9) | 167 | (57.0) | 135 | (69.2) | |||

| Other | 40 | (69.0) | 18 | (62.1) | 22 | (75.9) | |||

| Tumor stage | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Local | 395 | (61.4) | 210 | (56.9) | 185 | (67.5) | |||

| Regional | 338 | (56.6) | 172 | (52.9) | 166 | (61.0) | |||

| County-level poverty, % below FPL | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | 0.07 | ||||||

| ≤ 16 | 226 | (55.4) | 135 | (53.8) | 91 | (58.0) | |||

| 16.1–18.3 | 228 | (55.9) | 105 | (48.8) | 123 | (63.7) | |||

| ≥ 18.4 | 279 | (65.8) | 142 | (62.3) | 137 | (69.9) | |||

| County-level median Income | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| ≤ 33,502 | 270 | (66.0) | 143 | (60.6) | 127 | (73.4) | |||

| 33,503–41,946 | 240 | (60.0) | 130 | (57.3) | 110 | (63.6) | |||

| ≥ 41,947 | 223 | (51.7) | 109 | (47.2) | 114 | (57.0) | |||

| DPC physicians per 100K population | < 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.13 | ||||||

| ≤ 103.9 | 215 | (63.1) | 104 | (59.1) | 111 | (67.3) | |||

| 104–198.7 | 228 | (61.3) | 121 | (56.3) | 107 | (68.2) | |||

| ≥ 198.8 | 290 | (55.0) | 157 | (51.8) | 133 | (59.4) | |||

| TX-Mexico border | < 0.0001 | < 0.001 | < 0.05 | ||||||

| No | 553 | (56.3) | 283 | (51.7) | 270 | (62.1) | |||

| Yes | 180 | (69.8) | 99 | (67.4) | 81 | (73.0) | |||

| Region | < 0.05 | 0.9 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Metro | 576 | (57.7) | 316 | (55.2) | 260 | (61.2) | |||

| Non-metro | 157 | (64.9) | 66 | (54.6) | 91 | (75.2) | |||

| Year of diagnosis | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 2000–2004 | 459 | (59.9) | 283 | (56.3) | 176 | (66.9) | |||

| 2005–2007 | 274 | (57.8) | 99 | (51.8) | 175 | (61.8) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.89 | ||||||

| No | 289 | (61.5) | 147 | (59.3) | 142 | (64.0) | |||

| Yes | 444 | (57.7) | 235 | (52.7) | 209 | (64.5) | |||

| Radiation therapy | 0.12 | 0.97 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| No | 339 | (56.9) | 178 | (55.1) | 161 | (59.0) | |||

| Yes | 394 | (61.2) | 204 | (55.0) | 190 | (69.6) | |||

| Surgery | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.64 | ||||||

| No | 37 | (50.7) | 17 | (42.5) | 20 | (60.6) | |||

| Yes | 696 | (59.6) | 365 | (55.8) | 331 | (64.5) | |||

| Comorbidity scores | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.18 | ||||||

| 0 | 477 | (60.2) | 251 | (56.4) | 226 | (65.1) | |||

| 1–2 | 172 | (60.1) | 97 | (55.1) | 75 | (68.2) | |||

| ≥ 3 | 84 | (51.9) | 34 | (46.6) | 50 | (56.2) | |||

| Total | 733 | (59.1) | 382 | (55.0) | 351 | (64.3) | |||

After controlling for all demographic and treatment characteristics, Black patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients had lower adjusted odds of 1-year adherence (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.44–0.87) and also had lower odds of adherence if they initiated an AI (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.32–0.88) (Table 3). Hispanics did not have lower odds of AET adherence compared to non-Hispanic white patients. Notably, younger women (aged 20–34) and those with a comorbidity score of three or more had significantly lower odds of AET adherence compared to women aged 50–64 (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.20–0.68) and those with 0 comorbidity (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.48–0.98). Interestingly, Table 3 also shows that women who lived at the Texas–Mexico border had higher odds of AET adherence compared to those who did not (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.29–4.18). This finding was largely driven by patients who initiated with Tamoxifen in the Texas–Mexico border region (OR 2.84, 95% CI 1.27–6.37). We did not observe differences in AET adherence for women who lived in metropolitan regions compared to those that lived in non-metro regions (urban or rural), nor did we find an association between poverty level, chemotherapy use, or surgery and adherence to AET in this cohort of Medicaid patients.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratio of AET adherence in women with breast cancer, by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic areas

| Characteristics | Adherence to any AET at initiation | Adherence; initiated tamoxifen | Adherence; initiated AIs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 20–34 | 0.37 | (0.20,0.68) | < 0.01 | 0.49 | (0.25,0.96) | 0.04 | 0.15 | (0.02,1.42) | 0.10 |

| 35–49 | 0.78 | (0.61,1.01) | 0.06 | 0.94 | (0.66,1.33) | 0.72 | 0.85 | (0.52,1.38) | 0.51 |

| 50–64 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Black | 0.62 | (0.44,0.87) | 0.01 | 0.73 | (0.46,1.15) | 0.18 | 0.53 | (0.32,0.88) | 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 0.89 | (0.66,1.21) | 0.46 | 0.82 | (0.55,1.23) | 0.34 | 1.08 | (0.66,1.77) | 0.77 |

| Other | 1.55 | (0.85,2.82) | 0.15 | 1.35 | (0.60,3.07) | 0.47 | 2.06 | (0.81,5.22) | 0.13 |

| Tumor stage | |||||||||

| Local | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Regional | 0.82 | (0.64,1.06) | 0.13 | 0.94 | (0.67,1.31) | 0.70 | 0.66 | (0.44,0.99) | 0.05 |

| Poverty | |||||||||

| ≤ 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 16.1–18.3 | 0.97 | (0.69,1.36) | 0.86 | 0.75 | (0.49,1.17) | 0.21 | 1.3 | (0.73,2.30) | 0.37 |

| ≥ 18.4 | 0.91 | (0.56,1.48) | 0.70 | 0.85 | (0.44,1.65) | 0.63 | 1.01 | (0.47,2.17) | 0.98 |

| Median income | |||||||||

| ≤ 33,502 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 33,503–41,946 | 1.16 | (0.72,1.86) | 0.54 | 1.24 | (0.65,2.37) | 0.51 | 0.98 | (0.47,2.04) | 0.96 |

| ≥ 41,947 | 0.94 | (0.54,1.66) | 0.84 | 0.88 | (0.41,1.87) | 0.74 | 0.88 | (0.36,2.15) | 0.78 |

| DPC physicians per 100K population | |||||||||

| ≤ 103.9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 104–198.7 | 0.79 | (0.55,1.14) | 0.21 | 0.57 | (0.34,0.94) | 0.03 | 1.07 | (0.62,1.85) | 0.81 |

| ≥ 198.8 | 0.99 | (0.67,1.46) | 0.96 | 0.83 | (0.49,1.40) | 0.48 | 1.05 | (0.57,1.93) | 0.88 |

| TX–Mexico border | |||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 2.32 | (1.29,4.18) | 0.01 | 2.84 | (1.27,6.37) | 0.01 | 1.71 | (0.69,4.23) | 0.25 |

| Region | |||||||||

| Metro | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Non-metro | 1.37 | (0.88,2.13) | 0.16 | 0.88 | (0.48,1.62) | 0.68 | 1.93 | (0.98,3.82) | 0.06 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||||

| 2000–2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2005–2007 | 0.88 | (0.68,1.16) | 0.37 | 0.96 | (0.64,1.44) | 0.85 | 0.65 | (0.43,0.99) | 0.05 |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.93 | (0.71,1.22) | 0.60 | 0.81 | (0.57,1.16) | 0.26 | 1.04 | (0.68,1.59) | 0.84 |

| Radiation therapy | |||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.21 | (0.95,1.54) | 0.13 | 0.95 | (0.68,1.32) | 0.76 | 1.64 | (1.12,2.41) | 0.01 |

| Surgery | |||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.23 | (0.75,2.02) | 0.41 | 1.55 | (0.78,3.06) | 0.21 | 0.94 | (0.43,2.06) | 0.88 |

| Comorbidity scores | |||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1–2 | 0.99 | (0.74,1.32) | 0.93 | 0.93 | (0.63,1.35) | 0.69 | 1.24 | (0.75,2.05) | 0.40 |

| ≥ 3 | 0.68 | (0.48,0.98) | 0.04 | 0.61 | (0.36,1.04) | 0.07 | 0.77 | (0.46,1.29) | 0.32 |

Discontinuing AET, or going 90 or more days without AET medication, was not significantly different between black and white patients at any time period (immediately, within 3 months, within 3–6 months, or within 6–9 months) (Table 4). However, patients aged 20–34 had between 2.4 and 3.4 times higher odds of discontinuing AET treatment immediately to within 6 months of initiating therapy compared to women aged 50–64. Patient who resided within the Texas–Mexico border region had 70% lower odds of discontinuing AET therapy after filling just 1 prescription compared to patients who did not live in the border region of Texas (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10–0.87). Surprisingly, Medicaid patients who received radiation therapy had lower odds of discontinuing AET therapy immediately (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.43–0.95) and within the first three months of treatment (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44–0.92) compared to patients who did not.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratio of AET discontinuation among women with breast cancer, by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic areas

| Characteristics | Immediate discontinuation | Discontinuation within 3 months | Discontinuation within 3–6 months | Discontinuation within 6–9 months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 20–34 | 2.49 | (1.14,5.45) | 0.02 | 3.26 | (1.62,6.58) | 0.00 | 3.41 | (1.35,8.61) | 0.01 | 1.26 | (0.36,4.46) | 0.72 |

| 35–49 | 1.5 | (1.00,2.25) | 0.05 | 1.52 | (1.04,2.22) | 0.03 | 1.11 | (0.67,1.82) | 0.68 | 0.88 | (0.51,1.49) | 0.63 |

| 50–64 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Black | 1.16 | (0.71,1.90) | 0.55 | 1.2 | (0.75,1.92) | 0.44 | 1.74 | (0.97,3.13) | 0.06 | 0.85 | (0.42,1.74) | 0.66 |

| Hispanic | 0.81 | (0.49,1.34) | 0.40 | 0.88 | (0.55,1.40) | 0.58 | 0.52 | (0.27,0.99) | 0.05 | 1.21 | (0.68,2.15) | 0.52 |

| Other | 0.71 | (0.27,1.88) | 0.49 | 0.78 | (0.31,1.92) | 0.58 | 1.16 | (0.42,3.19) | 0.77 | 0.23 | (0.03,1.77) | 0.16 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||||||||

| Local | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Regional | 1.33 | (0.89,2.00) | 0.17 | 1.46 | (1.00,2.14) | 0.05 | 0.91 | (0.56,1.49) | 0.72 | 0.72 | (0.43,1.22) | 0.22 |

| Poverty | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 16.1–18.3 | 1.22 | (0.72,2.06) | 0.47 | 1 | (0.61,1.64) | 0.99 | 1.35 | (0.69,2.64) | 0.38 | 0.78 | (0.42,1.45) | 0.43 |

| ≥ 18.4 | 1 | (0.45,2.25) | 1.00 | 1.05 | (0.50,2.19) | 0.90 | 1.1 | (0.41,2.99) | 0.85 | 0.35 | (0.13,0.94) | 0.04 |

| Median income | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 33,502 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 33,503–41,946 | 0.74 | (0.35,1.58) | 0.44 | 1.01 | (0.49,2.08) | 0.99 | 0.89 | (0.36,2.23) | 0.81 | 0.51 | (0.20,1.31) | 0.16 |

| ≥ 41,947 | 1.21 | (0.50,2.92) | 0.67 | 1.27 | (0.55,2.96) | 0.58 | 1.24 | (0.42,3.65) | 0.70 | 0.29 | (0.10,0.88) | 0.03 |

| DPC physicians per 100K population | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 103.9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 104–198.7 | 1.27 | (0.72,2.22) | 0.41 | 1.11 | (0.65,1.90) | 0.70 | 2.03 | (1.00,4.14) | 0.05 | 0.78 | (0.35,1.73) | 0.54 |

| ≥ 198.8 | 0.85 | (0.46,1.56) | 0.60 | 0.91 | (0.52,1.61) | 0.75 | 1.37 | (0.60,3.10) | 0.46 | 1.33 | (0.62,2.81) | 0.46 |

| TX–Mexico border | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.30 | (0.10,0.87) | 0.03 | 0.46 | (0.18,1.20) | 0.11 | 1.27 | (0.41,3.98) | 0.68 | 0.59 | (0.17,2.08) | 0.41 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Metro | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Non-metro | 0.99 | (0.49,2.01) | 0.99 | 0.94 | (0.48,1.80) | 0.84 | 1.68 | (0.74,3.79) | 0.21 | 0.63 | (0.25,1.57) | 0.32 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 2000–2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2005–2007 | 0.75 | (0.48,1.18) | 0.21 | 0.76 | (0.50,1.15) | 0.19 | 1.1 | (0.65,1.83) | 0.73 | 1.21 | (0.69,2.13) | 0.50 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.99 | (0.64,1.52) | 0.95 | 0.98 | (0.65,1.46) | 0.91 | 1.16 | (0.69,1.96) | 0.57 | 1.19 | (0.69,2.05) | 0.53 |

| Radiation therapy | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.64 | (0.43,0.95) | 0.03 | 0.63 | (0.44,0.92) | 0.02 | 0.87 | (0.55,1.39) | 0.57 | 0.85 | (0.51,1.39) | 0.51 |

| Surgery | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.08 | (0.49,2.38) | 0.85 | 0.76 | (0.38,1.49) | 0.42 | 1.05 | (0.40,2.80) | 0.92 | 0.58 | (0.23,1.44) | 0.24 |

| Comorbidity scores | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 1–2 | 1.03 | (0.65,1.65) | 0.89 | 1.01 | (0.65,1.57) | 0.97 | 1.12 | (0.64,1.94) | 0.69 | 1.19 | (0.66,2.15) | 0.57 |

| ≥ 3 | 1.53 | (0.89,2.61) | 0.12 | 1.48 | (0.90,2.46) | 0.12 | 1.19 | (0.59,2.40) | 0.64 | 1.28 | (0.63,2.58) | 0.49 |

The sample sizes vary across different discontinuous time group. For each group, n = 127, 149, 86, 76, respectively

Discussion

In this racially/ethnically diverse, low-income, Medicaid-insured cohort of women with breast cancer in Texas, we found that black patients had significantly lower odds of adherence to AET compared to white patients, but they were not more likely to discontinue AET therapy anytime within the first 12 months of first prescription. Studies that find a significant racial/ethnic difference in AET adherence are explained by household net worth [11], or out-of-pocket costs for medications, [24] both of which variables were either controlled for in our study or were not relevant to our population.

A suboptimal proportion of women (59.1%) were adherent to AET medication within the first 12 months after initiating therapy. This is lower than previous reports using similar claims-based methodology among non-elderly privately insured women, which reported 72–81% 12-month adherence to AET [37–41]. However, unlike our study, they did not include a large proportion of low-income minority women which are factors that are associated with lower likelihood of adherence [11, 16, 17]. Studies using state cancer registry and Medicaid-linked data in North Carolina [17] and New York [42] corroborate our adherence rates and find that adherence ranges from 59 to 60% within the first year of initiation. In the New Jersey Medicaid population, patients who were less indigent than our study found that adherence was slightly higher (70%) [12]. However, these studies did not specifically examine racial/ethnic differences in adherence. The lower rates of adherence could also be driven by age, since almost 40% of our study population was younger than age 50 and younger patients are less likely to be adherent [12, 41].

Alarmingly, black patients were significantly less likely to be adherent to AET compared to non-Hispanic white patients. However, they were not more likely to discontinue treatment. This suggests that while they possessed < 80% of AET medication during the 12-month period, they did not go longer than 90 days without medication. This is an insightful and significant finding because black patients, especially, could benefit from receiving mail-order medication if access to prescriptions is the main driver for having irregular fills. In privately insured populations, the ability to access medication through mail-order pharmacies is associated with better adherence to AET medication [41, 43]. Since having ≥ 80% of medication is associated with the benefits of a reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence and mortality [38, 44], having less than 80% may indicate that many patients did not receive the full benefits of AET medication, which may contribute to the breast cancer mortality disparity between black and white patients.

We did not observe any differences in AET adherence or discontinuation among patients that lived in Metropolitan vs non-Metro geographic locations. However, we did find that those who lived within the Texas–Mexico border region had higher odds of AET adherence compared to those that did not. This finding may mainly be driven by the high proportion of Hispanics that live in the region. While we studied adherence and discontinuation to AET but not cancer outcomes, this phenomenon might be explained by the Hispanic health paradox whereby Hispanics in the U.S. are less likely to suffer from chronic disease or die prematurely, despite high rates of poverty and less access to education and health care [45]. Philips found that Hispanics with a higher degree of social deprivation were associated with lower mortality among Hispanics in Texas [26]. Hispanics in this border region may have a higher degree of socioeconomic deprivation and may be culturally different (less acculturated) than Hispanics in other regions of Texas which may explain the observation that they have better medication adherence. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to find that breast cancer patients living within the Texas–Mexico border have better adherence to AET medication.

This study has several strengths and adds new information to the literature on AET adherence and discontinuation for the Medicaid population. Since Texas Medicaid data were linked with the Texas Cancer Registry data, we were able to assess the date of cancer diagnosis more accurately which allowed us to study AET adherence and discontinuation during the first year of initiating therapy. Next, we included baseline demographic and clinical characteristics which may have confounded the observed associations with adherence because prior reports on AET adherence strictly rely on medical claims data [39, 46].

Our study was limited first, by the population, which included only women < 65 years enrolled in Medicaid. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to older patients or those with private insurance which may have copayments or out-of-pocket costs for medications. Second, we did not have patient-reported measures for non-adherence and there could be unmeasured confounding factors affecting the validity of the study findings. Psychosocial factors related to the quality of care that women receive such as physician–patient communication, for example, may influence women’s AET adherence but could not be captured in this study [47, 48], or the adverse effects of the medication [49]. Third, calculating adherence using Medicaid prescription claims assumes that patients take the medications as often as they refill prescriptions. Some patients might have refilled AET medication but did not take it. Nevertheless, pharmacy records are considered as the most objective and accurate estimation of actual medication use in large populations over time [50, 51]. Finally, we only examined adherence and discontinuation within a 12-month period from the date of initiation; however, this may be the most critical period to study adherence, since non-adherence in subsequent years is low [37].

Conclusions

There were substantial racial and geographic disparities in AET adherence and discontinuation among Texas Medicaid-insured women with breast cancer. In these racially diverse Texas Medicaid-insured breast cancer patients, black patients were less likely to be adherent to AET treatment within 12 months of initiating therapy compared to non-Hispanic white patients. This was especially true for black patients that initiated AET with an AI but not among those that initiated with tamoxifen. However, they were not less likely to discontinue therapy. Future research should examine whether racial/ethnic differences in adherence to AET is associated with mortality. Still, expanding the access to prescription medication, such as mail-in pharmacy orders in Medicaid, could improve treatment adherence.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of the Texas Cancer Registry and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the creation of this database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibilities of the authors. At the time of the study, Albert J. Farias was a postdoctoral fellow supported by a University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health’s Cancer Education and Career Development Program grant from the National Cancer Institute (R25-CA57712). This study was also supported, in part, by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01-HS018956) and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP130051).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors declare full adherence to the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, Giantonio BJ, Ross RN, Teng Y, Wang M, Niknam BA, Ludwig JM, Wang W, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013;310(4):389–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banegas MP, Li CI. Breast cancer characteristics and outcomes among Hispanic Black and Hispanic White women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(3):1297–304. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2142-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du XL, Fang S, Meyer TE. Impact of treatment and socioeconomic status on racial disparities in survival among older women with breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31(2):125–32. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181587890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(4):323. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Clarke M, Cutter D, Darby S, McGale P, Pan HC, Taylor C, Wang YC, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haque R, Ahmed SA, Fisher A, Avila CC, Shi J, Guo A, Craig Cheetham T, Schottinger JE. Effectiveness of aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen in reducing subsequent breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2012;1(3):318–27. doi: 10.1002/cam4.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Hoctin-Boes G, Houghton J, Locker GY, Tobias JS, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):60–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, Paridaens R, Jassem J, Delozier T, Jones SE, Alvarez I, Bertelli G, Ortmann O, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1081–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, Buono D, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Kwan M, Gomez SL, Neugut AI. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(2):529–37. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, Gray R, Arriagada R, Raina V, Abraham M, Medeiros Alencar VH, Badran A, Bonfill X, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9869):805–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershman DL, Tsui J, Wright JD, Coromilas EJ, Tsai WY, Neugut AI. Household net worth, racial disparities, and hormonal therapy adherence among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):1053–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):602–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figs. 2013–2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banning M. Adherence to adjuvant therapy in post-menopausal breast cancer patients: a review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21(1):10–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livaudais JC, Lacroix A, Chlebowski RT, Li CI, Habel LA, Simon MS, Thompson B, Erwin DO, Hubbell FA, Coronado GD. Racial/ethnic differences in use and duration of adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast cancer in the women’s health initiative. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(3):365–73. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts MC, Wheeler SB, Reeder-Hayes K. Racial/Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in endocrine therapy adherence in breast cancer: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):e4–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3445–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3309–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adisa AO, Lawal OO, Adesunkanmi AR. Paradox of wellness and nonadherence among Nigerian women on breast cancer chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2008;4(3):107–10. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.42640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winterhalder R, Hoesli P, Delmore G, Pederiva S, Bressoud A, Hermann F, von Moos R group) SIGSpc. Self-reported compliance with capecitabine: findings from a prospective cohort analysis. Oncology. 2011;80(1–2):29–33. doi: 10.1159/000328317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella D, Fallowfield LJ. Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):167–80. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browall M, Ahlberg K, Karlsson P, Danielson E, Persson LO, Gaston-Johansson F. Health-related quality of life during adjuvant treatment for breast cancer among postmenopausal women. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorizio W, Wu AH, Beattie MS, Rugo H, Tchu S, Kerlikowske K, Ziv E. Clinical and biomarker predictors of side effects from tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(3):1107–18. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farias AJ, Du XL. Association between out-of-pocket costs, race/ethnicity, and adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence among Medicare patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):86–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts Texas: Medicaid and CHIP. 2018 Retrieved June, 2018 from https://www.kff.org/state-category/medicaid-chip/?state=TX.

- 26.Philips BU, Jr, Belasco E, Markides KS, Gong G. Socioeconomic deprivation as a determinant of cancer mortality and the Hispanic paradox in Texas, USA. Int J equity Health. 2013;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian N, Goovaerts P, Zhan FB, Chow TE, Wilson JG. Identifying risk factors for disparities in breast cancer mortality among African-American and Hispanic women. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(3):e267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pruitt SL, Lee SJ, Tiro JA, Xuan L, Ruiz JM, Inrig S. Residential racial segregation and mortality among black, white, and Hispanic urban breast cancer patients in Texas, 1995 to 2009. Cancer. 2015;121(11):1845–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guadagnolo BA, Liao KP, Giordano SH, Elting LS, Shih YC. Variation in intensity and costs of care by payer and race for patients dying of cancer in Texas: an analysis of registry-linked Medicaid, Medicare, and Dually Eligible Claims Data. Med Care. 2015;53(7):591–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du XL, Key CR, Dickie L, Darling R, Geraci JM, Zhang D. External validation of medicare claims for breast cancer chemotherapy compared with medical chart reviews. Med Care. 2006;44(2):124–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196978.34283.a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du XL, Key CR, Dickie L, Darling R, Delclos GL, Waller K, Zhang D. Information on chemotherapy and hormone therapy from tumor registry had moderate agreement with chart reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du X, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Information on radiation treatment in patients with breast cancer: the advantages of the linked medicare and SEER data. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(5):463–70. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du X, Freeman JL, Warren JL, Nattinger AB, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Accuracy and completeness of Medicare claims data for surgical treatment of breast cancer. Med Care. 2000;38(7):719–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(10):1075–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):556–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Gomez SL, Miles S, Neugut AI. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, Stratton S, Brouse CH, Hillyer GC, Grann VR, Hershman DL. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2534–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sedjo RL, Devine S. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(1):191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farias AJ, Hansen RN, Zeliadt SB, Ornelas IJ, Li CI, Thompson B. The association between out-of-pocket costs and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Yung RL, Hassett MJ, Chen K, Gesten FC, Roohan PJ, Boscoe FP, Sinclair AH, Schymura MJ, Schrag D. Initiation of adjuvant hormone therapy by Medicaid insured women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(14):1102–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farias AJ, Hansen RN, Zeliadt SB, Ornelas IJ, Li CI, Thompson B. Factors associated with adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among privately insured and newly diagnosed breast cancer patients: a quantile regression analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(8):969–78. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.8.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Crilly M, Thompson AM, Fahey TP. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(11):1763–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public health reports (Washington, DC: 1974) 1986;101(3):253–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hershman DL, Tsui J, Meyer J, Glied S, Hillyer GC, Wright JD, Neugut AI. The change from brand-name to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11):1–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Ratliff CT, Leake B. Racial/ethnic group differences in treatment decision-making and treatment received among older breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2006;106(4):957–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farias AJ, Ornelas IJ, Hohl SD, Zeliadt SB, Hansen RN, Li CI, Thompson B. Exploring the role of physician communication about adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer patients on active treatment: a qualitative analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(1):75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3389-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wouters H, Stiggelbout AM, Bouvy ML, Maatman GA, Van Geffen EC, Vree R, Nortier JW, Van Dijk L. Endocrine therapy for breast cancer: assessing an array of women’s treatment experiences and perceptions, their perceived self-efficacy and nonadherence. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(6):460–7 e462. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, Canning C, Platt R. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37(9):846–57. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steiner JF, Koepsell TD, Fihn SD, Inui TS. A general method of compliance assessment using centralized pharmacy records. Description and validation. Med Care. 1988;26(8):814–23. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]