Abstract

Background

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is a rare vascular tumour of the infancy and the first decade of life. It is locally aggressive and potentially life threatening when associated with consumptive coagulopathy, known as Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS). No consensus or guideline for the therapy has been reached because of the lack of prospective trials, and the different standard care suggestions are based on retrospective case series.

Case report

We report the case of a 9-month-old male with KHE and KMS in which the initial response, obtained with prednisone and vincristine, was subsequently consolidated and strengthened by long-term treatment with sirolimus, a mTOR inhibitor. A summary of the published data is presented as well.

Conclusions

The inhibition of mTOR pathway represents the most important therapeutic innovation introduced in the last few years for KHE. Our case shows the effectiveness and good tolerance of long-term therapy with sirolimus.

Keywords: Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma, Kasabach-Merrit syndrome, Sirolimus, Prednisone, Vincristine

Introduction

Kaposiform Hemangio-endothelioma (KHE) is a rare vascular tumour of the infancy and the first decade of life. KHE shows no sex predilection, is locally aggressive and potentially life threatening when associated with consumptive coagulopathy known as Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS). KHE has an incidence of 0.7/100.000/year,1 and it can appear anywhere over the body with a wide range of clinical presentations. Macroscopically KHE is characterised by the presence of abundant vascular structures that infiltrate the surrounding soft tissues, and it is structured as a tender mass that causes pain when platelets congest within the vessels, and coagulation cascade is activated. Tumour nodules have irregular borders and they are composed of fascicles of spindle endothelial cells which are positive for vascular markers like CD31 and CD34, and negative for Glut1, with a low Ki67 proliferative index, rare mitosis, no nuclear atypia, no necrosis. KHE shows no tendency to metastasize.2 KMS is usually associated with a reduction of platelets count and haemoglobin, a lengthening of prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and to a reduction of fibrinogen. No consensus or guideline for the therapy has been reached because of the lack of prospective trials, and the different standard care suggestions are based on retrospective case series. We report a severe case of KHE with KMS successfully treated with prednisone and vincristine, used to induce the initial response and subsequently consolidated and strengthened by long-term treatment with sirolimus. The inhibition of mTOR pathway by sirolimus is an important therapeutic innovation introduced in the last few years, and a review of the published data is discussed.

Case Report

A 9-month-old male was admitted to the emergency department several times in three months for respiratory and urinary tract infections, constipation, recurrent abdominal pain with globose abdomen, and failure to thrive. The blood exams showed a recurrent thrombocytopenia interpreted as resulting from infections. Screening for celiac disease was negative. In the last access to the emergency department blood exams showed thrombocytopenia (110 ×109/L) and anaemia (Hb 8,9 g/dl) with white blood cell 8.3 ×109/L, PT 1.26 (n.v 0.80–1.17), PTT 1.17 (v.n 0.80–1.20), fibrinogen 0.83 g/L (n.v 2–4), D-dimer >10.000 mcg/L (n.v < 0,25), antithrombin III 100% (n.v 70–130). In the following weeks, he manifested a progressive decrease in the number of platelets, with a minimum value of 9 × 109/L.

An ultrasound of the abdomen revealed a solid mass of about 6 × 2,3 cm in the retroperitoneal space, without clear margin, locally spread around the mesenteric vessels’ origins. The lesion was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1). A biopsy was performed: the histological features (Figure 2) and the immunophenotype with CD 31 (JC/70A) +, CD 34 (QBEND/10)+, GLUT1 −/+, PODOPLANIN (D2–40) +, PROTEIN S100 −, Herpes virus 8 (13B10) - were diagnostic for KHE and the clinical and laboratory features were indicative of KMS. The child started a 6-week therapy with prednisone at the dose of 2 mg/kg/d (with a slow tapering), an 8-week course of vincristine (0,05 mg/kg/week) associated with sirolimus (3 mg/m2), modulated to maintain a blood concentration within the therapeutic range of 7,5–10 ng/ml. During the following months, there was a progressive clinical improvement with a 4 kg weight increase in 5 months. Platelet count increased to > 50 ×109/L after 15 days of therapy and normalized (> 150 ×109/L) after 4 months. As of 31st January 2018, the patient was being treated with sirolimus for 20 months without any clinical or biochemical side effects or infection complication. The MRI performed at 1, 9, 16 months showed a progressive reduction of the mass (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abdominal MRI performed at 1, 9, 16 months.

(A) MRI at the diagnosis. Solid tissue hypointense on T2-weighted images with post-contrast enhancement extended in the retroperitoneal area surrounding all upper abdominal vessels, adrenal glands and the left renal hilum (61×12 mm, black arrows). Lesions with the same characteristics also interest the hepatic hilum (36×12mm, white arrow) and the mesenteric adipose tissue. Left kidney enlarged with pyelectasis. Pancreas enlarged with areas showing post-contrast enhancement at the body-tail level. Progressive reduction in mass size after 1 month (B), 9 months (C) and 19 months (D).

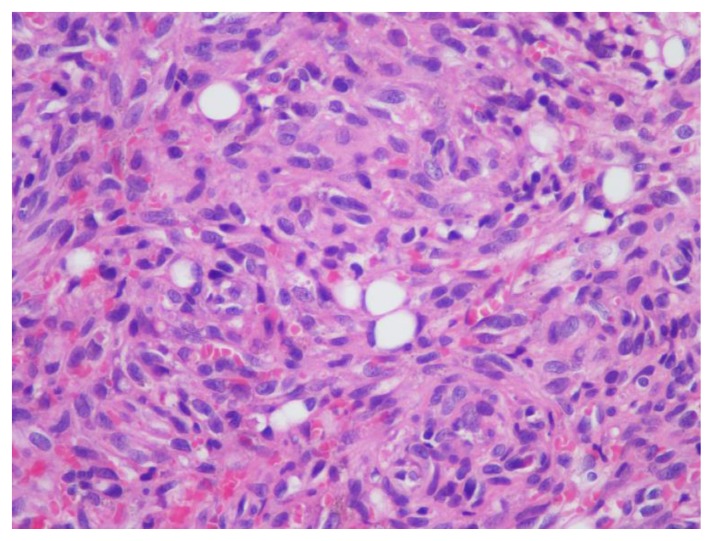

Figure 2.

Biopsy histological features.

Hematoxylin Eosin 400X magnification. Proliferation of neoplastic spindle cells, sparsely forming capillaries with red blood cells inside.

Discussion

We report a case of KHE with KMS that continues to respond to long-term treatment with sirolimus without side effects. We performed a review of the literature of all cases of KHE in patients under the age of 18 with the aim of defining typical characteristics of the disease. We analysed 42 papers1–3,8,9,11,12,15–49 including case reports, brief reports, case series, consensus, clinical letters, short communications, letters to the editor, retrospective studies, reviews and research letters. Data are summarised in table 1. The number of patients with KHE is 89 even if in 55% of cases the diagnosis is not supported by the histology. The most frequent sites are the extremities (43%). KMS is described in 59% of patients and it always occurs in the abdominal sites (100%). In nearly all cases it is already present at the diagnosis; when KMS is not present at the onset the risk to develop it over time is low. Moreover, KMS occurs in 87% of the masses > 5 cm and 100% of those > 10 cm, suggesting that dimensions are related to the risk of developing KMS (Table 1). No guideline has been defined, and different therapeutic medical and surgical treatments have been used for KHE with and without KMS. Radical surgery is one of possible treatment, and in cases of KMS it can resolve the coagulopathy, but unfortunately, most of the lesions are not surgically attackable, or they are only partially resectable. Embolization and sclerotherapy are other techniques rarely used due to the difficulty to cannulate small vessels and because of the risk of complications3. Radiotherapy has proven to be effective, but it is limited by important side effects.4,5 Steroid therapy, even at high doses, is widely used for this type of pathology and the literature data showed that 65% of the patients took a steroid (table 1). The most commonly used steroid is methylprednisolone (dose of 2 mg/kg/day) followed by prednisone and dexamethasone. This therapy often gives good results, but it is burdened by significant side effects especially when used for long time.21,24,31,49 Vincristine is an effective chemotherapeutic drug, administered once a week at a dosage of 0.05 mg/kg/dose. Vincristine has been used in 34% of patients especially in association with steroid therapy in patients with KMS. Vincristine resulted effective although the complete remission was rare and the duration of therapy is limited by side effects.6,7,8 Propranolol has been shown to be effective in the treatment of KHE,9 but the use in monotherapy is not able to control the disease.3 Interferon, antiangiogenic drugs such as bevacizumab10 and aspirin11 have been tested. Sirolimus is a mTOR inhibitor that is a serine/threonine kinase regulated by phosphoinositide-3-kinase. It is an important therapeutic option that has been increasingly used in the last few years. It affects cell growth and angiogenesis; it is also a powerful immunosuppressor and an antitumoral drug.1,12 In multiple studies the effectiveness of the use of Sirolimus and other mTOR inhibitor has been described,3,12,13,14 proving to be particularly active in vascular and lymphoproliferative disorders. Moreover, the mTOR inhibitors can be used in monotherapy even for long periods, being able to control cases of the non-completely regressed disease, and in spite of the necessity of constant control of blood levels, they resulted manageable and with little side effect. Literature data reported in table 1 show that 17% of patients received mTOR inhibitors, especially as second-line therapy after the use of steroids, vincristine, and others.8,19,20,21 It has been administered for months every day, in some cases twice a day, modulating the dose according to blood concentration (range 7–10 ng / ml).1,3,8,12,16,19,20,21,25,28,32,34,49 According to the data summarised in table 1, the most used therapeutic schemes are: steroid + other (33%) and steroid + vincristine + other (18%). In our case, the initial therapy of vincristine and prednisone was combined with sirolimus to obtain a regression of the KMS. Long-term therapy with sirolimus has shown to be effective in controlling the disease without side effects.

Table 1.

Features of patients.

| TOTAL NUMBER OF PATIENTS | 89 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEX | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Female | 28 (31,5) | ||

| Male | 28 (31,5) | ||

| Unknown | 33 (37) | ||

| AGE | Number of patients (%) | ||

| ≤ 1 y | 72 (81) | ||

| 1 to ≤ 10 y | 17 (19) | ||

| ≥ 10 y | 0 | ||

| Medium age | 7 m | ||

| Median age | 2 m | ||

| Minimun age | 0 d | ||

| Maximal age | 8y | ||

| SITE | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Extremities | 38 (43) | ||

| Head and neck | 16 (18) | ||

| Chest wall | 9 (10) | ||

| Mediastinal | 13 (15) | ||

| Abdominal wall | 1 (1) | ||

| Abdomen (deep) | 5 (6) | ||

| Retroperitoneum | 7 (8) | ||

| SIZE | Number of patients (%) | ||

| ≤ 5 cm | 10 (11) | ||

| > 5 cm of which >= 10 cm | 31 (35) 14 |

||

| Unknown | 48 (54) | ||

| HISTOLOGY | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Yes (surgery R2^) | 11 (12) | ||

| Yes (surgery R0^ – R1^) | 29 (33) | ||

| No | 49 (55) | ||

| KASABACH-MERRITT (KMS) | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Yes | 53 (59) | ||

| No | 15 (17) | ||

| Unknown | 21 (24) | ||

| At diagnosis | 52* (58) | ||

| KMS for SITE and SIZE | Yes (%) | No (%) | Unknown (%) |

| Extremities (tot 38) | 26 (68) | 9 (24) | 3 (8) |

| Head and neck (tot 16) | 9 (56) | 5 (31) | 2 (12) |

| Chest wall (tot 9) | 6 (66) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) |

| Mediastinal (tot 13) | 1 (8) | - | 12 (92) |

| Abdominal wall (tot 1) | 1 (100) | - | - |

| Abdomen (deep) (tot 5) | 5 (100) | - | - |

| Retroperitoneum (tot 7) | 5 (71) | - | 2 (29) |

| Size ≤ 5 cm (tot 10) | 2(20) | 7(70) | 1(10) |

| Size > 5 cm (tot 31) of which >= 10 cm (tot 14) | 27 (87) 14 (100) |

4 (13) | - |

| Size Unknown (tot 48) | 23 (48) | 25 (52) | - |

| INITIAL SURGERY | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Biopsy | 11 (12) | ||

| Conservative exeresis (macro/micro residues) | 27 (30) | ||

| Amputation | 2 (2) | ||

| Unknown | 49 (55) | ||

| NON SURGICAL-THERAPY | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Steroid | 58 (65) | ||

| Vincristine (VCR) | 30 (34) | ||

| Sirolimus/Everolimus | 15 (17) | ||

| Schemes | |||

| - No therapy/ not described | 11 (12) | ||

| - Steroid | 2 (2) | ||

| - Sirolimus | 2 (2) | ||

| - Other • | 15 (17) | ||

| - Steroid + VCR | 1 (1) | ||

| - Steroid + other • | 29 (33) | ||

| - VCR + Sirolimus + other • | 2 (2) | ||

| - Steroid + VCR + Sirolimus | 3 (3) | ||

| - Steroid + VCR + other • | 16 (18) | ||

| - Steroid + VCR + Sirolimus + other • | 8 (9) | ||

| SURVIVAL † | Number of patients (%) | ||

| Alive | 68 (76) | ||

| Dead | 3♣ (3) | ||

| Unknown | 18 (20) | ||

for one patient data not available.

R0, no residual tumor; R1, microscopic residual tumor; R2, macroscopic residual tumor.

Interferon (IFN), cyclophosphamide, propranolol, urea, embolization, gammaglobulin, ticlopidine.

Time of follow up not specified in the majority of cases.

A 13-day- old patient with 8 cm mass at head/neck level, KMS, undergoing surgical exeresis, treated with steroid + INF.

Died for multi-organ-failure 11 days after surgery. A 45-day-old patient with unknown size mediastinal mass, KMS, treated with steroid + VCR+ INF, unknown cause of death, A 3-months-old patient with unknown size mediastinal mass, KMS, treated with steroid+INF+radiotherapy, unknown cause of death.

Conclusions

KHE is a locally aggressive tumor, and it is potentially life threatening when associated with consumptive coagulopathy known as KMS. Although there is no univocal consensus on the therapy, our case shows that in cases of KHE with KMS a multidrug therapy (steroid + vincristine + mTOR inhibitor) followed by maintenance with the mTOR inhibitor monotherapy is a valuable option, with effective disease control and no relevant side effects. Future studies are needed to validate this approach and define the best duration of treatment.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Uno T, Ito S, Nakazawa A, Miyazaki O, Mori T, Terashima K. Successful treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with everolimus. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(3):536–538. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Q, Jiang L, Wu D, Kan Y, Fu F, Zhang D, Gong Y, Wang Y, Dong C, Kong L. Clinicopathological features of Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015 Oct 1;8(10):13711–8. eCollection 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu YE, Drolet BA, Blei F, et al. Variable response to propranolol treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, tufted angioma, and Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(5):934–938. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Li K, Dong K, Xiao X, Zheng S. Refractory Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon successfully treated with sirolimus, and a mini-review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42(4):401–404. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasabach HH, Merritt KK. Capillary hemangioma with extensive purpura: report of a case. Am J Dis Child. 1940;59(5):1063–1070. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1940.01990160135009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fahrtash F, McCahon E, Arbuckle S. Successful treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma with vincristine. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:506–510. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e001a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vivas-Colmenares GV, Ramirez-Villar GL, Bernabeu-Wittel J, Matute de Cardenas JA, Fernandez-Pineda I. The importance of early diagnosis and treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma complicated by Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5(1):91–93. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0501a18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahnel J, Lackner H, Reiterer F, Urlesberger B, Urban C. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: from vincristine to sirolimus. Klin Peadiatr. 2012;224(6):395–397. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filippi L, Tamburini A, Berti E, Perrone A, Defilippi C, Favre C, Calvani M, Della Bona ML, la Marca G, Donzelli G. Successful Propranolol Treatment of a Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma Apparently Resistant to Propranolol. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016 Jul;63(7):1290–2. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25979. Epub 2016 Apr 21. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Rafferty C, O’Regan GM, Irvine AD, et al. Recent advances in the pathobiology and management of Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 2015;171:38–51. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacFarland SP, Sullivan LM, States LJ, Bailey LC, Balamuth NJ, Womer RB, Olson TS. Management of Refractory Pediatric Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma With Sirolimus and Aspirin. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017 Dec 12; doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blatt J, Stavas J, Moats-Staats B, Woosley J, Morrell D. Treatment of childhood kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with sirolimus. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55(7):1396–1398. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Pineda I, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Chocarro G, et al. Long-term outcome of vincristine-aspirin-ticlopidine (VAT) therapy for vascular tumors associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1478–1481. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto H1, Ozeki M, Hori T, Kanda K, Kawamoto N, Nagano A, Azuma E, Miyazaki T, Fukao T. Successful Everolimus Treatment of Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma With Kasabach-Merritt Phenomenon: Clinical Efficacy and Adverse Effects of mTOR Inhibitor Therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016 Nov;38(8):e322–e325. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croteau, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: atypical features and risks of Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon in 107 referrals. J Pediatr. 2013 Jan;162(1):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakib, et al. Chemotherapy and Surgical Approach with Repeated Endovascular Embolizations: Safe Interdisciplinary Treatment for Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome in a Small Baby. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7:23–28. doi: 10.1159/000357300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, et al. Excellent outcome of medical treatment for Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: a single-center experience. Blood research. 2016;51:256–60. doi: 10.5045/br.2016.51.4.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drolet, et al. Consensus-Derived Practice Standards Plan for Complicated Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma. Jpeds. 2013;163(1):285–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammill, et al. Sirolimus for the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies in Children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1018–1024. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reichel, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: successful treatment with sirolimus. Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG) 2017:329–31. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12987. 1610-0379/2017/1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alaqeel, et al. Sirolimus for treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Jaad case reports. 2016;11:457–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaefer, et al. Long-term outcome for kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: A report of two cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:284–2. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mac-Mourne, et al. Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma: Five Patients with Cutaneous Lesion and Long Follow-Up. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(11):1087–1092. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascal, et al. Successful surgical management of congenital Kasabach–Merritt syndrome. Pediatrics International. 2017;59:89–102. doi: 10.1111/ped.13171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacobas, et al. Decreased vascularization of retroperitoneal kaposiform hemangioendothelioma induced by treatment with sirolimus explains relief of symptoms. Clinical Imaging. 2015;39:529–532. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackner, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of children with various complicated vascular anomalies. Eur J Pediatr. 2015 Dec;174(12):1579–84. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2572-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Due Wa, et al. Vascular tumors have increased 70 S6-kinase activation and are inhibited by topical rapamycin. Laboratory Investigation. 2013;93:1115–1127. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Sirolimus in the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137(2):e20153257. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shabtaie, et al. Neonatal Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma of the Spleen associated with Kasabach-Merritt Phenomenon. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams, et al. Comment on: Steroid-Resistant Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma: A Retrospective Study of 37 Patients Treated With Vincristine and Long-Term Follow Up. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:2056–2056. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, et al. Steroid-Resistant Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma: A Retrospective Study of 37 Patients Treated With Vincristine and Long-Term Follow-up. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:577–580. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, et al. Variable Response to Propranolol Treatment of Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma, Tufted Angioma, and Kasabach–Merritt Phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1518–1519. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallenstein, et al. Mediastinal Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma and Kasabach Merritt Phenomenon in a Patient with no Skin Changes and a Normal Chest CT. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2013:1–5. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2013.825356. Early Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan, et al. Rapidly Enlarging “Bruise” on the Back of an Infant. JAMA Dermatology. 2013;149(11):1337–8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahotra, et al. Congenital Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach Merritt Phenomenon Successfully Treated with Low-Dose Radiation Therapy. Pediatric Dermatology. 2014;31(5):595–598. doi: 10.1111/pde.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Monaco, et al. Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt Phenomenon: Successful Treatment with Embolization and Vincristine in Two Newborns. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brabash-Neila, et al. Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: Successful Treatment with Vincristine and Ticlopidine. Indian J Pediatr. 2012 Oct;79(10):1386–1387. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang, et al. Successful treatment of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome arising from kaposiform hemangioendothelioma by systemic corticosteroid therapy and surgery. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012 Oct;17(5):512–6. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams, et al. Vascular anomaly cases for the pediatric hematologist oncologists—An interdisciplinary review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017:e26716. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasui, et al. Kasabach-Merritt Phenomenon: A Report of 11 Cases From a Single Institution. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35:554–558. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318281558e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bota, et al. Infantile hemangiomas:a 7-year experience of a single-center. Clujul Medical. 2017;90(4):396–400. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Youn Kee, et al. Intestinal obstruction due to Kaposiform Hemagioendothelioma in a 1-month-old infant. Medicine. 2017;96:37. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Triana, et al. Pancreatic Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma Not Responding to Sirolimus. Eur J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e32–e35. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, et al. Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma in a nine-year-old boy with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 2017 Oct;179(1):9. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wlodeck, et al. A case of kaposiform haemangioendothelioma successfully and safely treated with sirolimus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Oct;42(7):825–827. doi: 10.1111/ced.13168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tasani, et al. Sirolimus therapy for children with problematic Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Dec;177(6):e344–e346. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arroyo Alonso, et al. Identical Presentation of Scapular Osteolysis in Two Patients with Thoracic Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma. Pediatric Dermatology. 2017:1–4. doi: 10.1111/pde.13114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sobrino-Fernandez, et al. Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma Presenting as Hydrops Fetalis. Pediatric Dermatology. 2017:1–2. doi: 10.1111/pde.13101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kai Li, et al. Sirolimus, a promising treatment for refractory Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:471–476. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1549-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]