Abstract

Objective

Metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells that allows for adaptation to their local environment is a hallmark of cancer. Interestingly, obesity- and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-driven hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) mouse models commonly exhibit strong steatosis in tumor cells as seen in human steatohepatitic HCC (SH-HCC), which may reflect a characteristic metabolic alteration.

Design

Non-tumor and HCC tissues obtained from diethylnitrosamine-injected mice fed either a normal or a high-fat diet (HFD) were subjected to comprehensive metabolome analysis, and the significance of obesity-mediated metabolic alteration in hepatocarcinogenesis was evaluated.

Results

The extensive accumulation of acylcarnitine species was seen in HCC tissues and in the serum of HFD-fed mice. A similar increase was found in the serum of patients with NASH-HCC. The accumulation of acylcarnitine could be attributed to the down-regulation of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2), which was also seen in human SH-HCC. CPT2 down-regulation induced the suppression of fatty acid β-oxidation, which would account for the steatotic changes in HCC. CPT2 knockdown in HCC cells resulted in their resistance to lipotoxicity by inhibiting the Src-mediated JNK activation. Additionally, oleoylcarnitine enhanced sphere formation by HCC cells via STAT3 activation, suggesting that acylcarnitine accumulation was not only a surrogate marker of CPT2 down-regulation but also directly contributed to hepatocarcinogenesis. HFD feeding and carnitine supplementation synergistically enhanced HCC development accompanied by acylcarnitine accumulation in vivo.

Conclusion

In obesity- and NASH-driven HCC, metabolic reprogramming mediated by the down-regulation of CPT2 not only enables HCC cells to escape lipotoxicity but also promotes hepatocarcinogenesis.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Metabolome, Acylcarnitine, CPT2, Metabolic reprograming

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and recent epidemiological studies have identified obesity as a significant risk factor in its development.1-3 Although various mechanisms have been suggested to underlie obesity-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis, including elevated proinflammatory cytokines, the dysregulation of adipokines, oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, as well as altered gut microbiota, the process remains poorly understood. 4-8

Cancer cells undergo characteristic metabolic changes to adapt to their local environment, so-called “metabolic reprogramming”. 9 Among the most well studied of these changes is the Warburg effect, in which cancer cells use aerobic glycolysis rather than the normal cellular pathway of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to generate the energy needed for the synthesis of nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids.10 Altered fatty acid (FA) metabolism is another property of cancer cells.11 FAs are synthesized de novo in most cancer cells, including HCC.11,12 In addition to their incorporation into the cell membrane, FAs serve as signaling molecules, storage compounds, and an energy source. However, in the obese, the increased intake of dietary FAs together with the lipolysis of visceral adipose tissue lead to enormous exogenous FA supplies to hepatocytes via the portal vein. This lipid-rich condition is a very characteristic environment for liver cancer, but how the malignant cells adapt to it and use it for their progression is unknown.

A histological variant of HCC, steatohepatitic HCC (SH-HCC), characterized by tumor cells with steatosis, pericellular fibrosis, and/or inflammatory infiltrates, has been recently recognized.13,14 Although SH-HCC occurs almost exclusively in patients with underlying steatohepatitis, with or without viral hepatitis infection, its pathogenesis has yet to be elucidated.

We recently reported a new mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-driven HCC, obtained by feeding a high-fat diet (HFD) to MUP-uPA mouse which expresses urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) under major urinary protein (MUP) promoter.6 Importantly, HCC arising in HFD-fed MUP-uPA mice is histologically similar to human SH-HCC. Furthermore, in the current study, we found that other obesity- and NASH-driven HCC mouse models, diethylnitrosamine (DEN) with HFD model and hepatocyte-specific PIK3CA transgenic (PIK3CA Tg) mouse model,4,15 also showed more prominent tumor steatosis than that in non-tumor hepatocytes. We therefore hypothesized that the marked steatosis of tumor cells is representative of characteristically altered metabolism in obesity-driven HCC and thus a key phenotype linking obesity, NASH, and HCC. Therefore, in the present study we carried out untargeted metabolomics profiling using mouse obesity-driven HCC tissues and found the extensive accumulation of acylcarnitine species in HCC. The significance of this finding in hepatocarcinogenesis was evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiments

MUP-uPA and PIK3CA Tg mice were described previously.6,15 Experimental protocols for animal models are described in the Supplementary materials and methods. All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of the University of Tokyo and the Institute for Adult Diseases, Asahi Life Foundation, and were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

In vitro experiments

We used DEN-induced mouse HCC cell line Dih10 for in vitro experiments.16 Details of biochemical analyses are described in the Supplementary materials and methods.

Histology

Immunostainings were performed as described previously (See Supplementary materials and methods).17

Metabolome analyses

Metabolite extraction and metabolome analysis were conducted at Human Metabolome Technologies (Tsuruoka, Yamagata, Japan). Details are provided in the Supplementary materials and methods.

Human samples

Serum acylcarnitine levels were evaluated in serum samples collected from 250 patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with (n = 28) and without (n = 222) HCC at the University of Tokyo Hospital from November 2011 to December 2015. The recruitment criteria of liver biopsy are described in the Supplementary materials and methods. We also collected serum samples from hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related HCC patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (n = 28) during the same period. All serum samples were collected in the morning of the day of liver biopsy and/or RFA after an overnight fast.

Human SH-HCC (n = 20) and conventional-HCC (n = 20) samples were obtained from patients who underwent surgical treatment at the University of Tokyo Hospital from January 2008 to December 2011. The diagnosis of SH-HCC was made as described previously (See Supplementary materials and methods).14

All patients provided informed consent. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Tokyo.

Statistical analyses

Details of the statistical analyses are described in the Supplementary materials and methods. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were performed using the ‘R’ statistical language (www.r-project.org).

Results

Acylcarnitine species accumulate markedly in obesity-driven HCC tissues

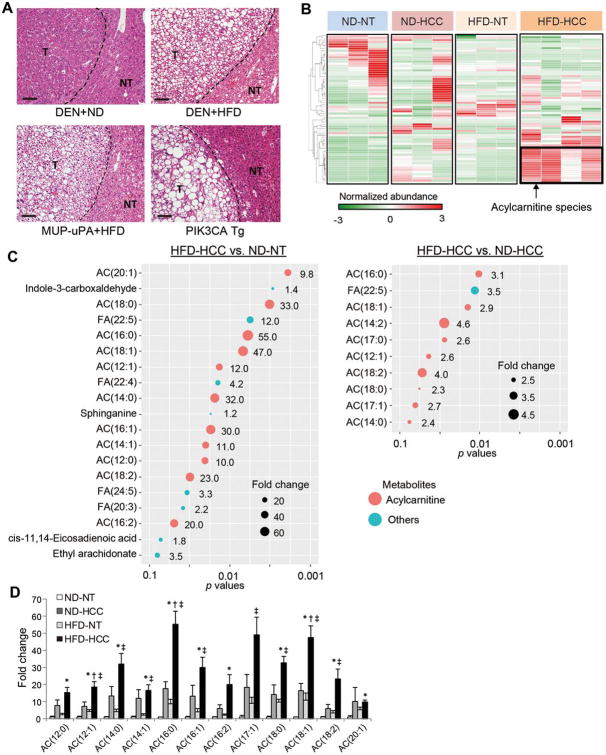

As we previously reported, HCC tumor cells of HFD-fed MUP-uPA mice exhibited marked steatosis that was more pronounced than that observed in non-tumor hepatocytes (Figure 1A). Similar findings were obtained in other obesity- and NASH-driven HCC mouse models, specifically, the DEN with HFD and PIK3CA Tg models (Figure 1A). Therefore, marked steatosis in tumor cells was a common feature among the obesity- and NASH-driven HCC mouse models.

Figure 1. Acylcarnitine species markedly accumulate in obesity-driven HCC tissues.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images of livers from mice with obesity- and NASH-driven HCC (scale bar, 100 μm). NT and T indicate non-tumor and tumor areas, respectively. (B) Hierarchical clustering analyses of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry data were performed using NT and HCC tissues obtained from DEN-injected 8-month-old mice fed a ND or a HFD (ND-NT, n = 3; ND-HCC, n = 3; HFD-NT, n = 3; HFD-HCC, n = 4). (C) Significantly accumulated metabolites in HFD-HCC tissues compared with ND-NT or ND-HCC tissues (false discovery rate < 0.25). Size of the circles indicates fold changes and color of the circles indicates types of metabolites (acylcarnitine species or others). AC, acylcarnitine; FA, fatty acid. (D) The bar graph shows the relative amounts of acylcarnitine species of various carbon chain lengths. The data are presented as the fold change relative to the average amount in ND-NT tissues (means ± SEM); * p < 0.05 vs. ND-NT tissues, †p < 0.05 vs. ND-HCC tissues, ‡p < 0.05 vs. HFD-NT tissues.

To explore the characteristic metabolic changes in obesity-driven HCC, paired non-tumor (NT) and HCC tissues obtained from DEN-injected 8-month-old mice kept on a normal diet (ND) or a HFD (ND-NT, ND-HCC, HFD-NT, and HFD-HCC tissues) were subjected to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)-based untargeted metabolomic profiling. The DEN model was used in this analysis because it enables comparisons of the metabolomic profile of HCC in mice fed a ND or HFD. Consistent with the previous report,4 HCC development was markedly enhanced in HFD-fed DEN-injected mice (Supplementary Figure 1). A cluster composed of metabolites specifically accumulated in HFD-HCC tissues was identified using a hierarchical clustering analysis (Figure 1B), and notably, various long-chain acylcarnitine species predominated (Figure 1C). ND-HCC and HFD-NT tissues also showed mildly increased levels of acylcarnitine species compared with ND-NT tissues; however, in both they were much lower than that in HFD-HCC tissues (Figure 1D). Therefore, in the following experiments we focused on the significance of acylcarnitine accumulation in obesity-driven HCC.

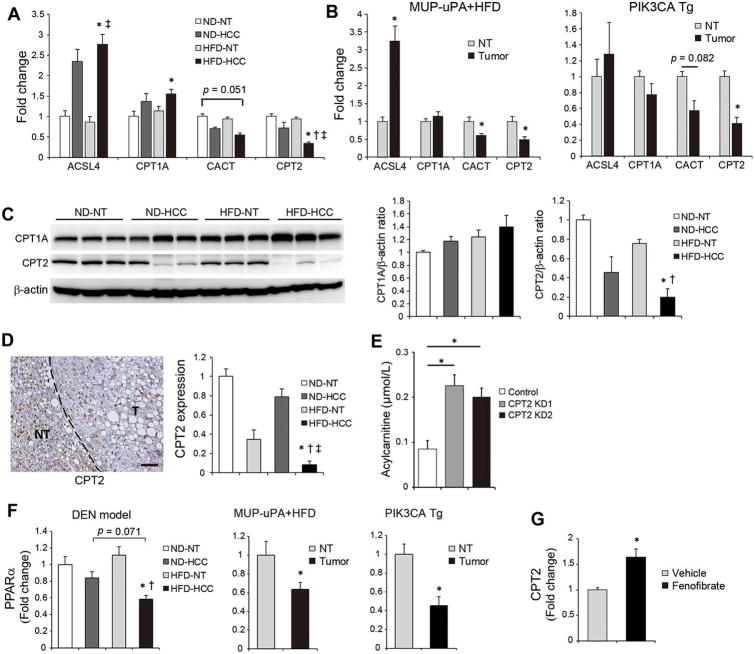

Expression of acylcarnitine metabolism-related genes in obesity-driven HCC

Acylcarnitine accumulation in HFD-HCC was further investigated by analyzing the expression of genes involved in acylcarnitine metabolism. Intracellular long-chain FAs are esterified to acyl-CoA by enzymes of the long-chain acyl-CoA synthase (ACSL) family and then converted to acylcarnitine via their conjugation to carnitine by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1). After its mitochondrial translocation via carnitine acylcarnitine translocase (CACT), acylcarnitine is converted back to acyl-CoA by CPT2 and then enters the fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) pathway, followed by the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.18 Among these acylcarnitine metabolism-related genes, increased expression of CPT1A (a hepatic isoform of CPT1) and ACSL4 (a member of the ACSL family, the expression of which is increased in human HCC) in ND-HCC and HFD-HCC tissues19 and decreased expression of CACT and CPT2 in HFD-HCC were detected (Figure 2A). Therefore, despite the enhanced conversion of FAs to acylcarnitine in HFD-HCC tissues, the reconversion of acylcarnitine to acyl-CoA was suppressed, which could account for the marked accumulation of acylcarnitine species. A similar expression pattern of acylcarnitine metabolism-related genes was observed in tumors arising in HFD-fed MUP-uPA and PIK3CA Tg mice: in particular, the downregulation of CPT2 in tumor tissues was a common finding (Figure 2B). We confirmed the significantly decreased CPT2 protein expression in HFD-HCC tissues by western blotting (WB) and immunostaining (Figures 2C, D, Supplementary figure 2A). Although CPT1A protein tended to be increased in HFD-HCC tissues, there were no statistically significant differences (Figure 2C). Thus, we further analyzed the significance of CPT2 down-regulation in subsequent experiments.

Figure 2. Expression of acylcarnitine-metabolism-related genes in obesity-driven HCC.

(A) The relative expression levels of the indicated genes determined using real-time PCR in NT and HCC tissues obtained from DEN-injected, ND- or HFD-fed mice (means ± SEM, n = 5 per group); * p < 0.05 vs. ND-NT tissues, †p < 0.05 vs. HFD-NT tissues. (B) The relative expression levels of the indicated genes determined using real-time PCR in NT and tumor tissues obtained from HFD-fed MUP-uPA mice (n = 6) and PIK3CA Tg mice (n = 5). The data are presented as the means ± SEM; * p < 0.05 vs. NT tissues. (C) WB analysis of CPT1A and CPT2 proteins in NT and HCC tissues obtained from DEN-injected, ND- or HFD-fed mice. Data were quantified using ImageJ software (means ± SEM, n = 5 per group); *p < 0.05 vs. ND-NT tissues, †p < 0.05 vs. HFD-NT tissues. (D) Representative IHC image of CPT2 in the liver obtained from DEN-injected HFD-fed mice (scale bar, 50 μm). Bar graph shows relative CPT2 expression levels in ND-HCC, HFD-NT, and HFD-HCC tissues compared with ND-NT tissues based on IF staining analysis (n = 7 per group); *p < 0.05 vs. ND-NT tissues, †p < 0.05 vs. ND-HCC tissues, ‡p < 0.05 vs. HFD-NT tissues. (E) Acylcarnitine concentrations in culture supernatants of control- and CPT2 KD-Dih10 cells (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05. (F) Relative PPARα mRNA expression levels determined using real-time PCR in tumor and non-tumor tissues obtained from DEN+HFD (n = 5 per group), MUP-uPA+HFD (n = 6), and PIK3CA Tg mice models (n = 5). The data are presented as the means ± SEM. DEN+HFD model; *p < 0.05 vs. ND-NT tissues, †p < 0.05 vs. HFD-NT tissues. MUP-uPA+HFD, and PIK3CA Tg mice models; *p < 0.05 vs. NT tissues. (G) Relative CPT2 mRNA expression levels determined using real-time PCR in Dih10 cells 24 h after incubation with fenofibrate (50 μM) or vehicle control (DMSO). The data are presented as the fold change relative to the average level in vehicle-treated control Dih10 cells (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05.

A human genetic disorder, CPT2 deficiency, results in increased serum acylcarnitine levels caused by impaired FAO.20 Similarly in this disease, CPT2 knockdown using siRNA in the DEN-induced mouse HCC cell line Dih1016 attenuated FAO with mild increase of lipid droplets after palmitic acid (PA) administration (Supplementary figure 2B-D), and Dih10 cells with stable CPT2 knockdown significantly increased the concentration of acylcarnitine in the culture medium (Figure 2E, Supplementary figure 2E). These observations suggested that the down-regulation of CPT2 can be a causal factor for acylcarnitine accumulation in HFD-HCC.

The CPT2 expression is mainly regulated by a transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα).21,22 All three mouse models, DEN+HFD, MUP-uPA+HFD, and PIK3CA Tg mice, exhibited significantly decreased PPARα expression in tumor tissues (Figure 2F). Consistent with a previous report,23 PPARα agonist fenofibrate upregulated CPT2 expression in Dih10 cells (Figure 2G). Therefore, decreased PPARα expression might partially explain the downregulation of CPT2 in obesity- and NASH-driven HCC.

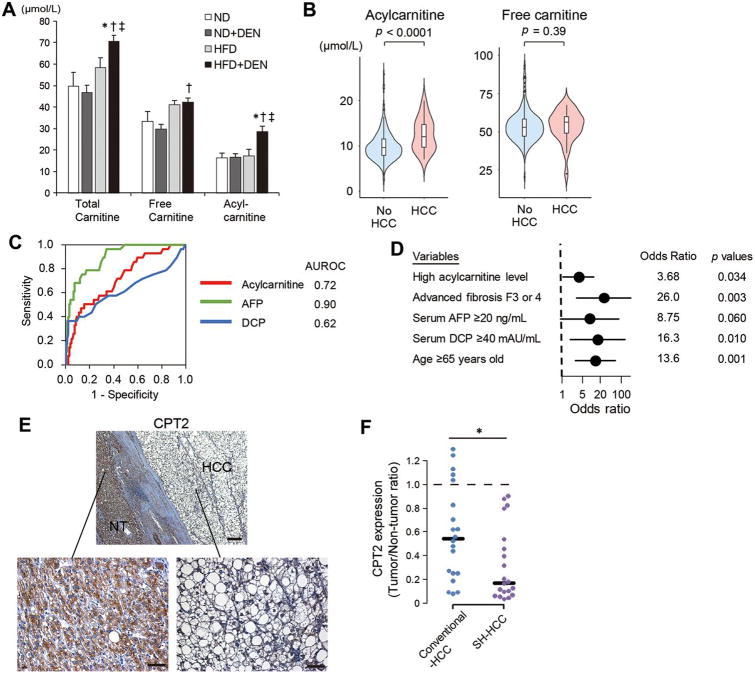

Analyses of serum acylcarnitine levels in human samples

Based on the observed release of acylcarnitine into the culture medium of HCC cells, total carnitine, free carnitine, and acylcarnitine levels were measured in serum samples collected from DEN-injected ND or HFD-fed mice and non-injected ND or HFD-fed mice. As shown in Figure 3A, serum acylcarnitine levels were significantly increased in HCC-bearing HFD-fed mice (Figure 3A). DEN administration did not affect the CPT2 expression levels in non-tumor tissues (Supplementary figure 2F). These findings suggested the acylcarnitine species accumulated in HCC tissues may be released into the bloodstream.

Figure 3. Serum acylcarnitine levels are elevated in patients with NAFLD-related HCC.

(A) Serum levels of total carnitine, free carnitine, and acylcarnitine in DEN-injected ND- or HFD-fed mice and non-injected age-matched ND- or HFD-fed mice (means ± SEM, n = 5 per group); *p < 0.05 vs. ND group, †p < 0.05 vs. ND+DEN group, ‡p < 0.05 vs. HFD group. (B) Violin plots of acylcarnitine and free carnitine serum levels in patients with NAFLD with or without HCC. (C) ROC curves of serum acylcarnitine, AFP, and DCP for the presence of HCC and their AUROCs. (D) Multivariable analysis for the presence of HCC using the logistic regression model. (E) Representative images of CPT2 immunostaining using human SH-HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver tissue (scale bar, 50 μm). (F) Relative CPT2 expression levels in conventional HCC and SH-HCC tissues compared with paired adjacent non-tumor liver tissues were analyzed using IF staining (n = 20 per group); *p < 0.05.

Then, we measured the serum levels of free carnitine and acylcarnitine in 250 biopsy-proven NAFLD patients with and without HCC (Table 1). While serum free carnitine levels were similar between the two groups, serum acylcarnitine levels were significantly higher in patients with HCC (Table 1, Figure 3B). Serum acylcarnitine levels increased gradually along with fibrosis progression and further increased in patients with HCC, whereas no such relationship was seen in free carnitine (Supplementary figure 3A). Although we also analyzed the relationships between serum levels of acylcarnitine and liver steatosis, inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning, there were no significant correlations (Supplementary figure 3B).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of NAFLD patients with or without HCC.

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 250) | HCC (n = 28) | Non HCC (n = 222) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male, n (%) | 146 (58) | 12 (43) | 134 (60) | 0.10 |

| Age | 57 (45-68) | 73 (67-78) | 54 (44-65) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 (25-31) | 27 (25-29) | 28 (25-31) | 0.34 |

| Acylcarnitine (μmol/L) | 9.7 (8.0-11.9) | 12.1 (9.7-14.8) | 9.6 (7.9-11.5) | <0.001 |

| Free carnitine (μmol/L) | 53.0 (47.3-58.7) | 56.3 (49.1-59.9) | 53.0 (47.3-58.7) | 0.39 |

| Platelet count (× 103/μL) | 202 (155-244) | 113 (81-145) | 211 (167-251) | <0.001 |

| AST (IU/L) | 39 (27-56) | 37 (31-46) | 40 (27-58) | 0.76 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 53 (31-85) | 28 (20-42) | 58 (34-87) | <0.001 |

| Serum AFP (ng/mL) | 2.6 (1.9-4.5) | 9.9 (5.2-17.1) | 2.4 (1.8-3.8) | <0.001 |

| Serum DCP (mAU/mL) | 16 (12-20) | 20 (13-35) | 15 (12-19) | 0.033 |

| Fibrosis (0/1/2/3/4), n (%) | 39/69/52/56/34 (16/28/21/22/14) | 0/0/1/10/17 (0/0/4/36/60) | 39/69/51/46/17 (18/31/23/21/8) | <0.001 |

| Steatosis (1/2/3), n (%) | 146/63/41 (58/25/16) | 27/0/1 (96/0/4) | 119/63/40 (54/28/18) | <0.001 |

| Lobular Inflammation (0/1/2/3), n (%) | 28/157/61/4 (11/63/24/2) | 8/16/4/0 (29/57/14/0) | 20/141/57/4 (9/64/26/2) | 0.030 |

| Hepatocyte ballooning (0/1/2), n (%) | 93/114/43 (37/46/17) | 10/13/5 (36/46/18) | 83/101/38 (37/45/17) | 1.00 |

| NASH diagnosis, n (%) | 214 (86) | 28 (100) | 186 (84) | 0.020 |

Data are expressed as median (25th-75th percentiles) unless otherwise indicated. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BMI, body mass index; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DCP, des-γ-carboxy-prothrombin; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

To explore the possibility of serum acylcarnitine as a biomarker of HCC in NAFLD patients, its diagnostic ability was evaluated using receiver operating characteristics curve (ROC) analysis. Area under the ROC curve (AUROCs) of serum acylcarnitine level was 0.72, which was inferior to that of α-fetoprotein (AFP) (0.90) but equivalent to that of des-γ-carboxy-prothrombin (DCP) (0.62) (Figure 3C). A higher serum level of acylcarnitine (> 12.6 μmol/L calculated by AUROC analysis) was an independent factor associated with the presence of HCC even after adjusting for confounding factors, such as age, AFP levels and fibrosis progression (Figure 3D, Supplementary table 1, 2). Moreover, in three NAFLD patients in whom serum samples were sequentially collected before and at the time of HCC diagnosis, the increase in serum acylcarnitine levels paralleled HCC development (Supplementary figure 3C). Thus, the serum acylcarnitine level may be a potential biomarker of HCC in NAFLD.

Notably, serum acylcarnitine levels in NAFLD-related HCC patients were significantly higher than those in HCV-related HCC patients who had similar background data except for BMI (Supplementary figure 3D, Supplementary table 3), implying that serum acylcarnitine levels are etiology-dependent and possibly high in patients with NAFLD-related HCC.

Next, we analyzed CPT2 protein expression using immunohistochemistry (IHC) in surgically resected human SH-HCC samples, and the CPT2 expression was almost completely absent in some SH-HCC samples (Figure 3E). Thus, we quantified expression levels of CPT2 in the tumor area and adjacent liver tissues in 20 SH-HCC (non-viral, n = 16; HCV, n = 4) using immunofluorescence (IF) staining and compared them with 20 conventional-HCC samples (HBV, n = 6; HCV, n = 14). Although CPT2 expression was decreased in both conventional-HCC and SH-HCC compared with paired adjacent liver tissues, SH-HCC exhibited a greater reduction of CPT2 than conventional-HCC (Figure 3F, Supplementary figure 3E). These findings were consistent with those in mice and supported the possibility that the increased serum acylcarnitine in HCC patients were derived from HCC tissues.

Furthermore, to examine whether CPT2 downregulation was involved also in fibrosis-related increase of acylcarnitine, we analyzed the expression levels of CPT2 mRNA in liver biopsy samples obtained from the above NAFLD cohort. However, there was no significant correlation between the serum acylcarnitine level and liver CPT2 expression irrespective of concomitant HCC (Supplementary figure 3F), suggesting that factors other than CPT2 were involved in liver fibrosis-related increase of serum acylcarnitine in NAFLD.

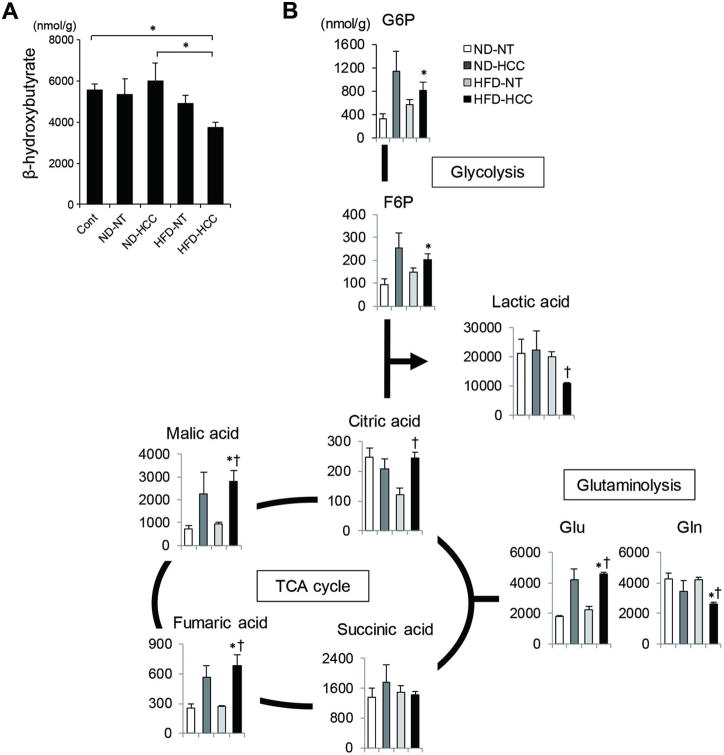

Capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry (CE–MS) in the analysis of the complete set of metabolites in HFD-HCC

The complete set of metabolites in mouse HCC samples was then analyzed using CE-MS. Consistent with the decreased CPT2 expression, the amount of β-hydroxybutyrate, a byproduct of FAO, was lower in HFD-HCC tissues, confirmed by direct measurements of β-hydroxybutyrate (Figure 4A, Supplementary figure 4), whereas higher levels of the components of the TCA cycle were detected (Figure 4B). Despite the increased amounts of the glycolytic metabolites, glucose-6-phosphate and fructose 6-phosphate, in HFD-HCC tissues, the amount of lactic acid was decreased, which is not the case in tumor cells exhibiting the Warburg effect (Figure 4B). This result indicated that glucose was utilized for oxidative phosphorylation. Additionally, the decreased glutamine and increased glutamate levels measured in the HFD-HCC samples pointed to the facilitated conversion of glutamine to glutamate in a process referred to as glutaminolysis, which is another major metabolic change that maintains the TCA cycle in cancer cells (Figure 4B).24 Collectively, our results showed the suppression of FAO in HFD-HCC tumor cells and the alternative use of glucose and glutamine in oxidative phosphorylation.

Figure 4. CE–MS analyses of obesity-driven HCC tissues.

(A) Concentration of β-hydroxybutyrate in NT and HCC tissues obtained from DEN-injected, ND- or HFD-fed mice, and liver tissues obtained from age-matched ND-fed control mice measured using the β-hydroxybutyrate assay kit. Data are the means ± SEM (n = 6 per group); *p < 0.05. (B) CE-MS analyses of NT and HCC tissues obtained from DEN-injected, ND- or HFD-fed, 8-month-old mice (ND-NT, n = 3; ND-HCC, n = 3; HFD-NT, n = 3; HFD-HCC, n = 4). Representative metabolites in the glycolytic pathway and TCA cycle are shown; *p < 0.05 vs. ND-NT tissues, †p < 0.05 vs. HFD-NT tissues.

CPT2 down-regulation enables HCC cells to adapt to lipid-rich conditions

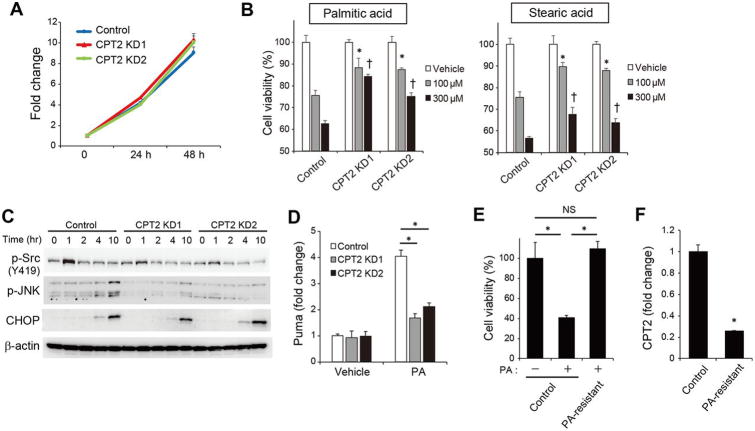

The role of CPT2 downregulation in hepatocarcinogenesis was further investigated by analyzing the effects of CPT2 knockdown on the behavior of Dih10 cells. Cellular growth was unaffected by CPT2 knockdown, even when observed over an extended period of time using the subcutaneous xenograft model (Figure 5A, Supplementary figure 5A). Excess amounts of saturated FAs, such as PA and stearic acid (SA), exert lipotoxicity; however, as shown in Figure 5B, CPT2 knockdown significantly suppressed PA - and SA-induced cell death. PA induces cell death through the phosphorylation of JNK and the subsequent up-regulation of Puma,25 as we were also able to demonstrate in Dih10 cells. However, both cellular events were significantly attenuated by CPT2 knockdown (Figure 5C, D). Recently, CPT2-mediated FAO was reported to induce Src activation through phosphorylation at Y419,26 which plays a critical role in saturated FA-induced JNK activation.27,28 In fact, PA -induced Src phosphorylation at Y419 was attenuated by CPT2 knockdown (Figure 5C), and Src inhibitor suppressed PA-induced cell death (Supplementary figure 5B). Although ER stress has also been implicated in PA-induced JNK activation,29 induction of the ER stress marker CHOP in CPT2 knockdown cells was similar to that in control cells (Figure 5C). These results suggested that CPT2 down-regulation attenuated lipotoxicity by inhibiting the Src-mediated JNK activation. Furthermore, we established PA-resistant Dih10 cells by chronic exposure to 50% lethal concentration of PA. The PA-resistant cells acquired similar growth capacity even in the PA containing media and revealed significantly decreased expression of CPT2 (Figure 5E, F). These results suggest that HCC cells avoid the lipotoxicity induced by the lipid-rich cellular environment by down-regulating CPT2.

Figure 5. CPT2 down-regulation enables HCC cells to adapt to a lipid-rich environment.

(A) Growth curve of control, CPT2 knockdown1 (KD1), and CPT2 KD2 Dih10 cells (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group). (B) Control, CPT2 KD1, and CPT2 KD2 Dih10 cells were incubated with PA and SA at the indicated concentrations for 24 h, after which cell viability was assessed (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05 vs. control Dih10 cells incubated with 100 μM PA or SA, †p < 0.05 vs. control Dih10 cells incubated with 300 μM PA or SA. (C) Control, CPT2 KD1, and CPT2 KD2 Dih10 cells were incubated with 200 μM PA and the expression levels of the indicated proteins were then assessed using WB at the indicated time points. (D) Relative expression levels of Puma were determined using real-time PCR in control, CPT2 KD1, and CPT2 KD2 Dih10 cells 10 h after their incubation with 200 μM PA or the vehicle control (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05. (E) PA-resistant Dih10 cells were established by their chronic exposure to 50% of the lethal concentration of PA (75 μM) for 1 week. Control and PA-resistant Dih10 cells were incubated with 100 μM PA or control media for 48 h, after which cell numbers were assessed (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05. (F) Relative expression levels of CPT2 were determined using real-time PCR in control and PA-resistant Dih10 cells (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05.

Oleoylcarnitine enhances the self-renewal of HCC cells through STAT3 activation

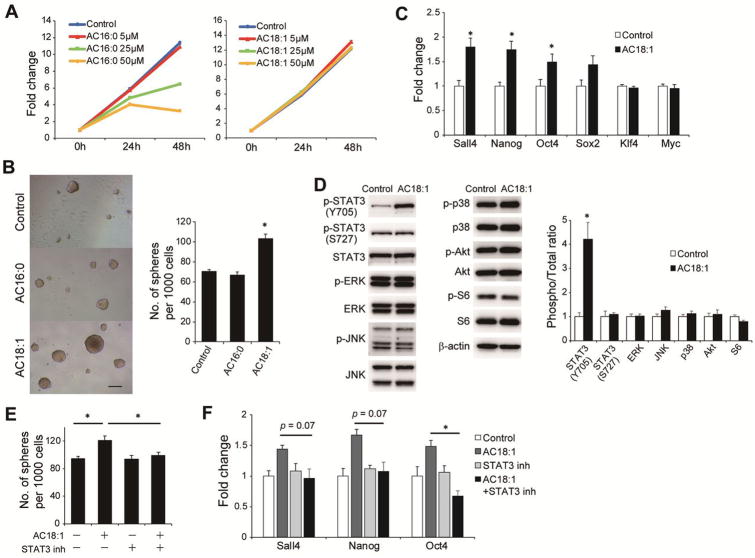

We then investigated whether the accumulation of acylcarnitine species in HFD-HCC tissues is a surrogate marker of CPT2 down-regulation or contributes directly to the promotion of HCC. Therefore, the effects of oleoylcarnitine (AC18:1) and palmitoylcarnitine (AC16:0), two abundantly accumulated acylcarnitine species in HFD-HCC, on cellular growth were investigated using Dih10 cells. As shown in Figure 6A, neither AC18:1 nor AC16:0 promoted cell growth, and high concentration of AC 16:0 (≥25 μM) was rather toxic to HCC cells. Since the concentration of acylcarnitine species in the tissues of obese mice is 5–10 μM,30 in subsequent experiments AC18:1 and AC16:0 concentrations of 5 μM were used.

Figure 6. AC18:1 enhances the self-renewal of HCC cells via STAT3 activation.

(A) Growth curve of Dih10 cells incubated with AC16:0 or AC18:1 at the indicated concentrations. (B) Sphere formation assays of Dih10 cells with 5 μM AC16:0, 5 μM AC18:1, or control medium. Bar graph shows the total number of spheres per well (means ± SEM from 8 wells per group); *p < 0.05 vs. the control. Representative images are shown (scale bar, 200 μm). (C) Relative expression levels of stem cell markers as determined by real-time PCR in Dih10 cells incubated for 24 h with 5 μM AC 18:1 or the vehicle control (means ± SEM from 3 wells per group); *p < 0.05. (D) Dih10 cells were incubated with 5 μM AC18:1 for 24 h, after which the expression levels of the indicated proteins were assessed by WB. Data were quantified using the ImageJ software (means ± SEM, n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05. (E, F) Effects of the STAT3 inhibitor WP1066 (2 μM) on AC18:1-induced promotion of sphere formation (E) and the enhanced expression of stem cell marker mRNAs in Dih10 cells (F). Data are the means ± SEM (n = 3 per group); *p < 0.05.

The effects of AC16:0 and AC18:1 on the self-renewal of HCC cells were evaluated in sphere formation assays. Remarkably, AC18:1 but not AC16:0 promoted sphere formation in Dih10 cells (Figure 6B). In accordance with this, AC18:1 increased the expression of several stem cell markers, including Sall4, Nanog, and Oct4 (Figure 6C). We therefore also assessed the activation status of several oncogenic mediators, including STAT3, ERK, JNK, p38, Akt, and S6, which have been reported to be involved in the HFD-mediated promotion of HCC induced by DEN,4 in AC18:1-supplemented Dih10 cells and found significantly increased phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 with a peak at 24 h (Figure 6D, Supplementary figure 6A). The expression of STAT3 downstream target genes, Mcl-1 and Survivin, was also increased by AC18:1 supplementation (Supplementary figure 6B). In addition, both AC18:1-induced spheroid formation and the enhanced expression of stem cell markers were abolished in cells treated with the STAT3 inhibitor WP1066 (Figure 6E, F). This finding suggested that AC18:1 contributes directly to hepatocarcinogenesis by conferring stem cell properties to cancer cells through STAT3 activation.

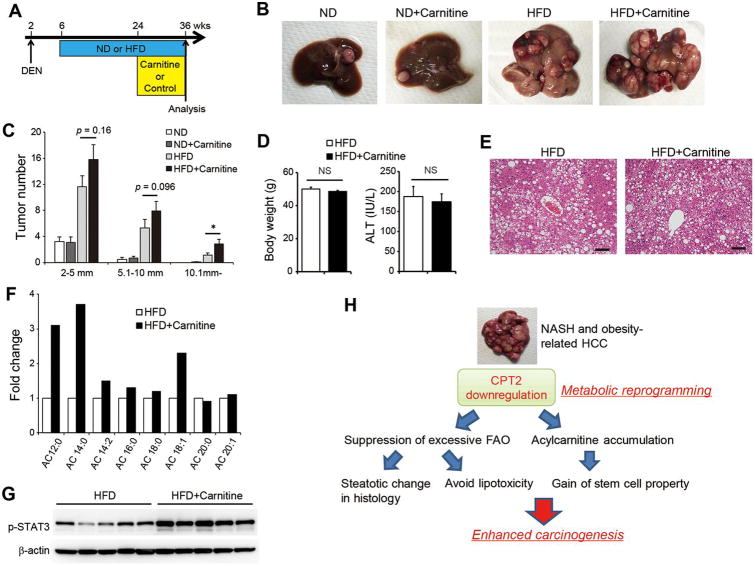

HFD feeding and carnitine supplementation synergistically enhance acylcarnitine accumulation and hepatocarcinogenesis

In humans, the consumption of red meat and saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of HCC development.31 Because red meat is a carnitine-rich food,32 we hypothesized that saturated fat and carnitine-containing red meat synergistically accelerate hepatocarcinogenesis through acylcarnitine accumulation. We therefore supplemented DEN-injected ND-fed or HFD-fed mice with L-carnitine by adding it to their drinking water and then compared tumorigenicity in these mice vs. those provided with non-supplemented drinking water (Figure 7A). Although L-carnitine supplementation did not cause a change in tumor formation in ND-fed mice, it significantly enhanced HCC development in HFD-fed mice (Figure 7B, C), without affecting HFD-induced body weight gain, liver steatosis, or serum alanine aminotransferase levels (Figure 7D, E). However, L-carnitine supplementation increased the amounts of acylcarnitine species, including AC 18:1, in HCC tissues (Figure 7F). Consistent with the in vitro experiments, L-carnitine supplementation increased STAT3 phosphorylation in HCC tissues (Figure 7G). Thus, HFD feeding and carnitine supplementation synergistically promoted hepatocarcinogenesis, and these results further support the tumor promoting effects of acylcarnitine.

Figure 7. HFD feeding and carnitine supplementation synergistically promote hepatocarcinogenesis.

(A) Protocol for L-carnitine supplementation in combination with HFD feeding of DEN-injected mice. The mice were randomly assigned to the ND (n = 12), ND + carnitine (n = 12), HFD (n = 15), and HFD + carnitine groups (n = 14). (B, C) Effects of L-carnitine supplementation on HCC development. Representative images of the livers (B) and tumor numbers (C) from each group of mice are shown. The data are presented as the means ± SEM; *p < 0.05 vs. the HFD group. (D, E) Effects of L-carnitine supplementation on HFD-induced body weight gain, elevation of ALT levels, and liver steatosis. (D) Bar graphs show the body weight and serum ALT levels in the HFD and HFD + carnitine groups. The data are presented as the means ± SEM. (E) Representative H&E-stained images of the non-tumor area of the livers from mice in the HFD and HFD + carnitine groups (scale bar: 100 μm). (F) Relative amounts of acylcarnitine species of various carbon chain lengths in HCC tissues from the HFD and HFD + carnitine groups. Three tumors from each group were pooled and the amounts of acylcarnitine species measured. The data are presented as the fold change relative to the level in the HFD group. (G) WB analysis of STAT3 phosphorylation in HCC tissues from the HFD and HFD + carnitine groups. (H) Proposed mechanisms of obesity- and NASH-driven enhanced carcinogenesis.

Discussion

The cellular adaptations caused by metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells can be clonally selected during tumorigenesis, and altered metabolism is a hallmark of cancer.9 In comprehensive analyses of metabolomics profiling using mouse HCC samples, we identified the extensive accumulation of acylcarnitine species in obesity-driven HCC tissues. We then showed that the down-regulation of CPT2 was a major cause of acylcarnitine accumulation and a common feature in mouse models of obesity- and NASH-driven HCC and human SH-HCC. Consistent with a recent study using liver specific CPT2 knockout mice,33 CPT2 down-regulation resulted in FAO suppression, which would explain, at least in part, the steatotic change characteristic of hepatic cancer cells. Although FAO efficiently generates energy and is utilized by most cancer cells for their progression, excessive FAO as a byproduct of high intracellular fat levels leads to excessive electron flux in the electron transport chain and metabolic stress that can cause cell death.34 In patients with NASH, the increased dietary intake of FAs and the lipolysis of visceral adipose tissue lead to an enormous exogenous supply of FAs to the liver through the portal vein. Although lipotoxic hepatocyte death is an important promoter of NASH-driven HCC,6 HCC cells must survive in the lipid-rich environment. HCC cells in which CPT2 was knocked down acquired resistance to lipotoxicity by inhibiting the Src-mediated JNK activation, and decreased CPT2 expression was also a feature of the lipotoxicity-resistant HCC cells established by chronic exposure to PA. Consistent with our results, the genetic ablation of CPT2 in adipose tissues suppressed HFD-induced oxidative stress via FAO inhibition in a recent study.35 Therefore, the down-regulation of CPT2 may enable HCC cells to adapt to the lipid-rich environment and thus avoid lipotoxicity (Figure 7H).

Although JNK plays a tumor-promoting role in hepatocarcinogenesis,36,37 its roles are complex and context-dependent.38 JNK-mediated hepatocyte death promotes hepatocarcinogenesis by inducing inflammation and compensatory regeneration,36 whereas JNK-mediated tumor cell death can suppress HCC development.39,40 In NASH patients, although JNK-mediated lipotoxic hepatocyte death is an important driving force of HCC, HCC cells must survive in the lipid-rich environment. Therefore, we consider that avoiding cell death by attenuating saturated FAs-induced JNK activation through CPT2 downregulation is beneficial for HCC cells in NASH.

Our results also demonstrated that acylcarnitine accumulation was not simply a surrogate marker of CPT2 downregulation but contributed directly to hepatocarcinogenesis. Recent studies highlighted the effects of acylcarnitine species on various pathophysiological conditions, such as cardiac ischemia, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation;30,32,41 however, little is known about the role of these compounds in carcinogenesis. In this study, AC18:1 promoted sphere formation in cultured HCC cells through the STAT3-mediated up-regulation of stem cell factors. Furthermore, the extensive accumulation of acylcarnitine in response to HFD feeding and L-carnitine supplementation enhanced STAT3 activation and promoted HCC development in vivo. The IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway was previously shown to play an important role in the transformation of liver cancer stem cells.42,43 Thus, CPT2 down-regulation not only enables HCC cells to escape from lipotoxicity but also promotes hepatocarcinogenesis via the accumulation of acylcarnitine-mediated STAT3 activation. Although we showed the decreased PPARα expression partially explains the CPT2 downregulation in obesity- and NASH-related HCC, the mechanism underlying the PPARα downregulation in HCC remains unknown. Therefore, further studies are needed on this issue.

Conversely, hypocarnitinemia sometimes occurs in cachectic cirrhotic patients,44 and L-carnitine supplementation has been reported to improve hepatic encephalopathy and muscle cramp.45,46 A significant correlation was observed between serum and liver tissue carnitine concentrations,47 and thus L-carnitine supplementation to compensate for carnitine deficiency is beneficial for cirrhotic patients. However, some reports showed that cirrhotic patients have hypercarnitinemia.48 Such a discrepancy might be caused by differences in the etiology of cirrhosis, nutritional status, dietary pattern, and severity of the cirrhosis. Indeed, serum carnitine levels tended to be higher in NAFLD-HCC patients than C-HCC patients in our study (Supplementary figure 3C). Importantly, to achieve a beneficial effect of carnitine supplementation, conservation of FAO pathway is considered mandatory. We showed that FAO in HFD-HCC was suppressed due to downregulation of CPT2, which was confirmed in human HCC, especially in SH-HCC, and a recent study analyzing global gene expression profiling of HCC also showed significant deregulation of FAO in HCC tissues.49 Additionally, FAO in the liver tissues of NASH patients was reported to be impaired due to decreased activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain,50 consistent with our results of increased serum acylcarnitine in NAFLD patients. Although carnitine supplementation under normal FAO function is not harmful, carnitine supplementation under impaired FAO in combination with high amounts of FAs leads to extensive accumulation of acylcarnitine species, which may exert tumor-promoting effects, as shown in this study, and also toxic effects on normal tissues.51 Indeed, L-carnitine supplementation did not promote HCC development under ND in our study. Because previous studies showing beneficial effects of carnitine were mostly based on short-term studies conducted in hepatitis virus-related cirrhosis, the long-term effect of carnitine supplementation on NASH-related cirrhosis, especially in patients with HCC, still needs to be explored.

We found significantly higher serum acylcarnitine levels in patients with NAFLD than without HCC and identified higher serum acylcarnitine as an independent factor associated with the presence of HCC even after adjusting for confounding factors. In previous metabolomic analyses of human HCC tissue samples, the levels of the acylcarnitine species AC18:1 and AC16:0 were significantly higher in HCC than in NT tissues.12 Additionally, consistent with our results, a recent study showed high serum acylcarnitine levels in patients with HCC.52 These findings suggest that serum acylcarnitine levels may be a potential biomarker of HCC. However, acylcarnitine species can also be released from other tissues besides the liver, and HCC may induce metabolic deregulation in other organs. Therefore, the direct relationship between serum acylcarnitine levels and HCC tissue acylcarnitine levels should be further investigated.

In contrast to red meat and saturated fat, the consumption of n-3 polyunsaturated FAs-rich fish has been reported to reduce the risk of HCC.53 Indeed, the amount of eicosapentaenoic acid (FA20:5) which can activate PPARα 54 was much lower in HFD-HCC tissues compared with ND-NT tissues (0.08 fold) in our metabolomic analysis. Therefore, fish-based diet combined with calorie restriction and exercise may be beneficial to prevent HCC in obese patients.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, obesity is defined as BMI ≥ 30 and most patients in our NAFLD cohort are classified as overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9). However, Asians have higher risk of obesity-related morbidity and mortality at lower BMI, and therefore, the Western Pacific Regional Office of WHO proposed an alternative definition of overweight (BMI 23.0–24.9) and obesity (BMI ≥ 25) for Asian populations.55 According to this definition, we used the term ‘obesity’ in the title.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not provide direct in vivo evidence of the tumor-promoting effect of CPT2 downregulation, and thus further studies such as knockout mouse studies are needed. Second, the sample size for our metabolomic analysis was relatively small. Analysis using a larger sample size should be conducted to clarify metabolic rearrangements in obesity- and NASH-related HCC in more detail.

In summary, comprehensive metabolome analyses identified the extensive accumulation of acylcarnitine species following CPT2 down-regulation in obesity-driven HCC tissues. CPT2 down-regulation not only enables HCC cells to escape lipotoxicity but also promotes hepatocarcinogenesis through acylcarnitine-mediated STAT3 activation. Therefore, up-regulating the expression of CPT2 may be a therapeutic option for obesity- and NASH-driven HCC.

Supplementary Material

- What is already known about this subject?

- - Obesity has been recognized as a significant risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development.

- - Cancer cells undergo characteristic metabolic change to adapt to their local environment, so-called “metabolic reprogramming”.

- - HCC can survive even in a lipid-rich environment, leading to lipotoxicity; however, how this environment aids in the progression has not been elucidated.

- What are the new findings?

- - HCC adapts to this lipid-rich environment through downregulation of CPT2, a key enzyme of fatty acid β-oxidation.

- - Oleoylcarnitine, the metabolite which accumulates through suppression of fatty acid β-oxidation, can enhance hepatocarcinogenesis via STAT3 activation.

- - Serum acylcarnitine levels are higher in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NALFD)-related HCC than in those without HCC.

- How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

- - Upregulation of CPT2 may be therapeutic for obesity- and NAFLD-driven HCC.

- - Acylcarnitine may be a biomarker of NAFLD-related HCC.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by Uehara Memorial Foundation (N.F. and H.N.), JSPS KAKENHI Grant number 15K19313, Viral Hepatitis Research Foundation of Japan, Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science, Bristol-Myers Squibb Research Grant (H.N.), Program for Basic and Clinical Research on Hepatitis from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED under Grant Number JP17fk0210304 (H.N. and K.K.), and AMED-CREST under Grant Number JP17gm0710004 (H.N.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- ACSL

long-chain acyl-CoA synthase

- AFP

α-fetoprotein

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- AUROC

area under the receiver operating characteristics curve

- CACT

carnitine acylcarnitine translocase

- CE–MS

capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry

- CPT

carnitine palmitoyltransferase

- DCP

des-γ-carboxy-prothrombin

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FA

fatty acid

- FAO

fatty acid β-oxidation

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IF

immunofluorescence

- LC–MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- ND

normal diet

- PA

palmitic acid

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

stearic acid

- SH-HCC

steatohepatitic HCC

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared

References

- 1.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(12):1118–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348(17):1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujiwara N, Nakagawa H, Kudo Y, et al. Sarcopenia, intramuscular fat deposition, and visceral adiposity independently predict the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell. 2010;140(2):197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilg H, Hotamisligil GS. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Cytokine-adipokine interplay and regulation of insulin resistance. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):934–45. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakagawa H, Umemura A, Taniguchi K, et al. ER stress cooperates with hypernutrition to trigger TNF-dependent spontaneous HCC development. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(3):331–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimoto S, Loo TM, Atarashi K, et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013;499(7456):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagawa H. Recent advances in mouse models of obesity- and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(17):2110–8. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i17.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science (New York, NY) 2009;324(5930):1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, et al. Cellular fatty acid metabolism and cancer. Cell Metab. 2013;18(2):153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budhu A, Roessler S, Zhao X, et al. Integrated metabolite and gene expression profiles identify lipid biomarkers associated with progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and patient outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):1066–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.054. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salomao M, Remotti H, Vaughan R, et al. The steatohepatitic variant of hepatocellular carcinoma and its association with underlying steatohepatitis. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(5):737–46. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibahara J, Ando S, Sakamoto Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with steatohepatitic features: a clinicopathological study of Japanese patients. Histopathology. 2014;64(7):951–62. doi: 10.1111/his.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kudo Y, Tanaka Y, Tateishi K, et al. Altered composition of fatty acids exacerbates hepatotumorigenesis during activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Hepatol. 2011;55(6):1400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He G, Yu GY, Temkin V, et al. Hepatocyte IKKbeta/NF-kappaB inhibits tumor promotion and progression by preventing oxidative stress-driven STAT3 activation. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(3):286–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa H, Hikiba Y, Hirata Y, et al. Loss of liver E-cadherin induces sclerosing cholangitis and promotes carcinogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(3):1090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322731111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schooneman MG, Vaz FM, Houten SM, et al. Acylcarnitines: reflecting or inflicting insulin resistance? Diabetes. 2013;62(1):1–8. doi: 10.2337/db12-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang YC, Wu CH, Chu JS, et al. Involvement of fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 in hepatocellular carcinoma growth: roles of cyclic AMP and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(17):2557–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i17.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gempel K, Kiechl S, Hofmann S, et al. Screening for carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency by tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2002;25(1):17–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1015109127986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto T, Cook WS, Qi C, et al. Defect in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-inducible fatty acid oxidation determines the severity of hepatic steatosis in response to fasting. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):28918–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910350199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrero MJ, Camarero N, Marrero PF, et al. Control of human carnitine palmitoyltransferase II gene transcription by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor through a partially conserved peroxisome proliferator-responsive element. The Biochemical journal. 2003;369(Pt 3):721–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrescu AD, McIntosh AL, Storey SM, et al. High glucose potentiates L-FABP mediated fibrate induction of PPARalpha in mouse hepatocytes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1831(8):1412–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wise DR, Thompson CB. Glutamine addiction: a new therapeutic target in cancer. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010;35(8):427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cazanave SC, Mott JL, Elmi NA, et al. JNK1-dependent PUMA expression contributes to hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(39):26591–602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JH, Vithayathil S, Kumar S, et al. Fatty Acid Oxidation-Driven Src Links Mitochondrial Energy Reprogramming and Oncogenic Properties in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;14(9):2154–65. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holzer RG, Park EJ, Li N, et al. Saturated fatty acids induce c-Src clustering within membrane subdomains, leading to JNK activation. Cell. 2011;147(1):173–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kant S, Standen CL, Morel C, et al. A Protein Scaffold Coordinates SRC-Mediated JNK Activation in Response to Metabolic Stress. Cell Rep. 2017;20(12):2775–83. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaffenbach KT, Gentile CL, Nivala AM, et al. Linking endoplasmic reticulum stress to cell death in hepatocytes: roles of C/EBP homologous protein and chemical chaperones in palmitate-mediated cell death. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;298(5):E1027–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00642.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoin CS, Knotts TA, Adams SH. Acylcarnitines--old actors auditioning for new roles in metabolic physiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(10):617–25. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman ND, Cross AJ, McGlynn KA, et al. Association of meat and fat intake with liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in the NIH-AARP cohort. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(17):1354–65. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nature medicine. 2013;19(5):576–85. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J, Choi J, Scafidi S, et al. Hepatic Fatty Acid Oxidation Restrains Systemic Catabolism during Starvation. Cell Rep. 2016;16(1):201–12. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serra D, Mera P, Malandrino MI, et al. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in obesity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(3):269–84. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J, Ellis JM, Wolfgang MJ. Adipose fatty acid oxidation is required for thermogenesis and potentiates oxidative stress-induced inflammation. Cell Rep. 2015;10(2):266–79. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakurai T, Maeda S, Chang L, et al. Loss of hepatic NF-kappa B activity enhances chemical hepatocarcinogenesis through sustained c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(28):10544–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603499103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hui L, Zatloukal K, Scheuch H, et al. Proliferation of human HCC cells and chemically induced mouse liver cancers requires JNK1-dependent p21 downregulation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118(12):3943–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI37156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Das M, Garlick DS, Greiner DL, et al. The role of JNK in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes & development. 2011;25(6):634–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.1989311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxena NK, Fu PP, Nagalingam A, et al. Adiponectin modulates C-jun N-terminal kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin and inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1762–73. 73.e1-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakagawa H, Hirata Y, Takeda K, et al. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 inhibits hepatocarcinogenesis by controlling the tumor-suppressing function of stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2011;54(1):185–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.24357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutkowsky JM, Knotts TA, Ono-Moore KD, et al. Acylcarnitines activate proinflammatory signaling pathways. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;306(12):E1378–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00656.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He G, Dhar D, Nakagawa H, et al. Identification of liver cancer progenitors whose malignant progression depends on autocrine IL-6 signaling. Cell. 2013;155(2):384–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin L, Amin R, Gallicano GI, et al. The STAT3 inhibitor NSC 74859 is effective in hepatocellular cancers with disrupted TGF-beta signaling. Oncogene. 2009;28(7):961–72. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rudman D, Sewell CW, Ansley JD. Deficiency of carnitine in cachectic cirrhotic patients. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1977;60(3):716–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI108824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malaguarnera M, Pistone G, Elvira R, et al. Effects of L-carnitine in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(45):7197–202. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i45.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakanishi H, Kurosaki M, Tsuchiya K, et al. L-carnitine Reduces Muscle Cramps in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2015;13(8):1540–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiraki M, Shimizu M, Moriwaki H, et al. Carnitine dynamics and their effects on hyperammonemia in cirrhotic Japanese patients. Hepatol Res. 2017;47(4):321–27. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krahenbuhl S, Reichen J. Carnitine metabolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 1997;25(1):148–53. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v25.pm0008985281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bjornson E, Mukhopadhyay B, Asplund A, et al. Stratification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Based on Acetate Utilization. Cell Rep. 2015;13(9):2014–26. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Carreras M, Del Hoyo P, Martin MA, et al. Defective hepatic mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2003;38(4):999–1007. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Primassin S, Ter Veld F, Mayatepek E, et al. Carnitine supplementation induces acylcarnitine production in tissues of very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-deficient mice, without replenishing low free carnitine. Pediatric research. 2008;63(6):632–7. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816ff6f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yaligar J, Teoh WW, Othman R, et al. Longitudinal metabolic imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mouse models identifies acylcarnitine as a potential biomarker for early detection. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20299. doi: 10.1038/srep20299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawada N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, et al. Consumption of n-3 fatty acids and fish reduces risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1468–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flachs P, Rossmeisl M, Bryhn M, et al. Cellular and molecular effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on adipose tissue biology and metabolism. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2009;116(1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/CS20070456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.WHO, International Association for the Study of Obesity, International Obesity Task Force. Australia: 2000. The Asia-Pacific perspective: Redefining obesity and its treatment. http://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/5379/0957708211_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.