Abstract

Genetic testing of minors is advised only for conditions in which benefits of early intervention outweigh potential psychological harms. This study investigated whether genetic counseling and test reporting for the CDKN2A/p16 mutation, which confers highly elevated melanoma risk, improved sun protection without inducing distress. Eighteen minors (Mage = 12.4, SD = 1.9) from melanoma-prone families completed measures of protective behavior and distress at baseline, 1 week (distress only), 1 month, and 1 year following test disclosure. Participants and their mothers were individually interviewed on the psychological and behavioral impact of genetic testing 1 month and 1 year post-disclosure. Carriers (n = 9) and noncarriers (n = 9) reported significantly fewer sunburns and a greater proportion reported sun protection adherence between baseline and 1 year post-disclosure; results did not vary by mutation status. Anxiety symptoms remained low post-disclosure, while depressive symptoms and cancer worry decreased. Child and parent interviews corroborated these findings. Mothers indicated that genetic testing was beneficial (100%) because it promoted risk awareness (90.9%) and sun protection (81.8%) without making their children scared (89.9%); several noted their child’s greater independent practice of sun protection (45.4%). In this small initial study, minors undergoing CDKN2A/p16 genetic testing reported behavioral improvements and consistently low distress, suggesting such testing may be safely implemented early in life, allowing greater opportunity for risk-reducing lifestyle changes.

Keywords: CDKN2A/p16, Familial melanoma, Genetic counseling, Children, Prevention, Sun protection

Introduction

Genetic testing for disease predisposition has the potential to alert individuals to elevated risk status before disease development, potentially aiding in the control or even prevention of disease. In the case of melanoma, genetic test reporting for the CDKN2A/p16 (hereafter referred to as p16) mutation, which confers a 28–76% lifetime risk of melanoma (Begg et al. 2005; Bishop et al. 2002), has been found to promote both prevention and detection behaviors (Aspinwall et al. 2008; Aspinwall et al. 2014; Aspinwall et al. 2013b), though some studies have yielded mixed results (Bergenmar et al. 2009; Kasparian et al. 2009). Importantly, these behavioral benefits have been achieved without inducing either short-term or long-term psychological distress (Aspinwall et al. 2013a).

Genetic testing for melanoma risk may be especially important for minors, as childhood sun exposure (Whiteman et al. 2001), including history of sunburns (Gandini et al. 2005; Whiteman et al. 2001), is a major risk factor for melanoma. Given the importance of reducing early-childhood sun exposure, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends sun protection for fair-skinned individuals as young as 10 (Bibbins-Domingo et al. 2016). Yet, sun protection is often inadequate among minors in the general population. For instance, 69% of minors aged 11–18 reported a sunburn in the past year, with less than half reporting regular use of sunscreen or other sun protection methods (Cokkinides et al. 2006). Minors face many barriers to effective use of sun protection, such as perceptions that sunscreen is inconvenient and that protective clothing interferes with their activities as well as a lack of awareness of the risk of skin cancer from sun exposure (Dadlani and Orlow 2008). Even minors with a parent who has a personal history of skin cancer report inadequate engagement in sun protection (Geller et al. 2007; Glenn et al. 2015). Genetic testing and counseling may help to educate minors from melanoma-prone families about their elevated risk and methods for reducing it, thereby increasing motivation to engage in sun protection despite these barriers.

Healthcare professionals and researchers have raised concerns that predictive genetic testing for disease risk may be psychologically harmful for minors, potentially leading to stigma or discrimination, including being treated differently by family members due to their test result (Botkin et al. 2015). As such, the American Society for Human Genetics currently recommends use of predictive genetic testing in minors only for conditions in which there is a clinical intervention that can be delivered in childhood (Botkin et al. 2015). For example, BRCA testing is not generally advised for minors because procedures undertaken to reduce cancer risk are not recommended prior to adulthood (Burke et al. 1997). However, predictive genetic testing of minors is accepted for familial adenomatous polyposis and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (Borry et al. 2010; Brandi et al. 2001; Half et al. 2009), because increased screenings and prophylactic removal of the organ that contributes to risk are advised prior to adulthood. As both of these conditions have an early age of onset with clear intervention, the benefits to testing appear to outweigh potential harms. In the case of familial melanoma, it is unknown whether genetic testing will result in risk-reducing changes to sun protection habits and skin screening.

Essential to any recommendation to provide genetic testing is a careful consideration of the potential costs and benefits to children and families. Although parents have expressed strong interest in p16 genetic testing of their children and believe that testing would improve their children’s practice of prevention and screening behaviors (Taber et al. 2010), there have been no empirical studies that have investigated whether genetic testing and counseling for melanoma risk lead to these improvements for minors. In the present study, we examined the prospective impact of providing p16 test results, along with education about melanoma risk and its management, to children aged 10–15 over a 1-year period, using self-report measures of skin screening and sun protection, well-validated measures of psychological distress, and structured interviews with both the minor and his/her mother.

Method

Recruitment, Eligibility Criteria, and Retention

Minors were eligible for the BRIGHT (Behavior, Risk Information, Genetics and Health, Trial) Kids study if they (1) had a parent who had tested positive for the p16 mutation, (2) were ages 10–15, (3) had no personal history of melanoma, and (4) had not previously received genetic testing for melanoma risk. A lower age limit of 10 was selected because it was unclear if children younger than this age would understand the counseling session and genetic testing procedures. An upper age limit of 15 was selected because older participants were eligible for a concurrent adult-focused genetic testing study. Participants were compensated with gift cards totaling $40 for parents and $45 for children. Additionally, families who lived more than 50 miles away received a $50 gift card at each visit to assist with travel expenses.

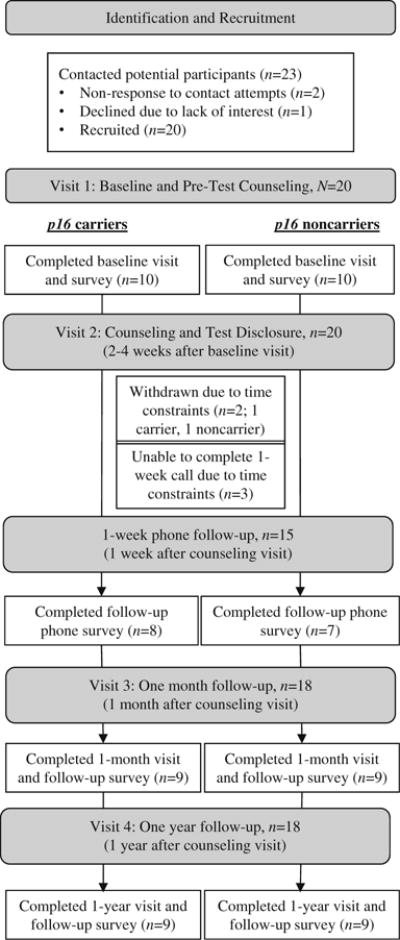

Through research records from studies of melanoma-prone families, 23 children were identified as potentially eligible for BRIGHT Kids (see Fig. 1). Twenty children were enrolled and completed the baseline visit. Two participants from the same family were withdrawn from the study before the 1-month follow-up due to their busy schedule; data from these participants are not reported. The 18 remaining participants came from 11 families. Eight of these families (72.7%) included a parent who had participated in one of our prior studies in which genetic test results for melanoma risk were reported (Aspinwall et al. 2013b; Taber et al. 2015). In five families (45.5%), one parent had a prior melanoma diagnosis. Three participants (one carrier, two noncarriers) were unable to complete the 1-week follow-up phone call due to schedule constraints but completed all other study activities. Thus, our sample for analysis was 15 minors for 1-week outcomes and 18 minors for 1-month and 1-year outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Participant identification, recruitment, and retention for the BRIGHT Kids Study

Procedures

BRIGHT Kids study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah. Participants completed a total of four in-person sessions (baseline/pre-test counseling, test disclosure/counseling, 1 month post-disclosure, 1 year post-disclosure) and one assessment by phone 1 week post-disclosure to assess potential short-term distress. This short-term evaluation of distress was undertaken because it is possible that short-term elevations in distress in the days and week following test disclosure would not be captured by the measures at 1 month post-disclosure and because this early assessment of distress allowed the opportunity to monitor whether any individual minors required additional follow-up and counseling. Self-report measures of behavior and distress were completed at each in-person visit. Reflectance spectroscopy measures to assess tanning at the wrist and face were also taken at each visit (see supplementary Reflectance Spectroscopy Analyses). In-person assessments were scheduled from April to mid-October, months in which the average daily ultra violet (UV) index is at least moderate in the local area (“UV Index: Annual Time Series, 2012” 2013).

Genetic Counseling Protocol

Following completion of baseline surveys, all participants completed an initial “pre-test” genetic counseling session with a certified genetic counselor (see supplementary BRIGHT Kids Genetic Counseling Protocol). At the pre-test session, all enrolled siblings and at least one parent participated in the same session. The purpose of the session was to provide sufficient education about melanoma and p16 genetic testing to enable participants to decide whether to undergo testing. Information was presented in a simplified manner with age-appropriate visual aids in order to improve comprehension. Parents and their children were given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss their decision with the genetic counselor at any point in the session.

The post-test genetic counseling session was completed separately for each child, and at least one parent attended each session, which typically took place 2–4 weeks following the initial visit. Genetic counselors began by briefly reviewing information on melanoma and the p16 gene and then provided the child’s test result. All children (regardless of mutation status) received identical education about how to check their skin and how to reduce sun exposure. Children who tested positive additionally received the recommendation to undergo annual total body skin examinations from a medical professional.

Measures

Sunburn Frequency

At each study visit, participants were asked about sunburn frequency using a single item from the Sun Habits Survey (Glanz et al. 2008): “In the past month, how many times did you have a red OR painful sunburn that lasted a day or more?” Response options ranged from “0” to “5 or more.”

Sun Protection Behaviors

Sun protection behaviors were assessed at each study visit by a modified version of the Sun Habits Survey (Glanz et al. 2008), which assesses the frequency of several specific sun protection behaviors. An example item asks, “How often did you use sunscreen with an SPF (sun protection factor) of 30+?” Responses options ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Because these specific methods can overlap in effectiveness, we categorized as adherent participants who reported using at least one of the primary methods of protection (sunscreen, long pants, long-sleeved shirt, hat, shade, avoiding peak exposure) “often” or “always” (Aspinwall et al. 2014).

Skin Self-Exam Frequency

At each study visit, participants were asked about their frequency of skin self-exams (SSE) using an item developed for this study: “In the past month, how often have you checked your skin for new or changed moles or growth?” Response options ranged from “Never” to “Every Day.” For analysis, participants were categorized as checking their skin either never or at least once during the past month.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed at each study visit and the 1-week post-disclosure phone call using the Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (Kovacs 2010). This well-validated measure consisted of 28 items, for which participants selected one of three options corresponding to how they had been feeling in the last week. Scores were computed using manual guidelines and could range from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms.

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed at each study visit and the 1-week post-disclosure phone call using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Children (Spielberger and Edwards 1973). This measure consists of 20 items, with response options of “Hardly Ever,” “Sometimes,” or “Often.” Participants were asked to select the option that corresponded to how he or she usually feels (Trait Inventory). On this measure, scores can range from 20 to 60 with higher scores indicating greater anxiety.

Cancer Worry

Cancer worry was assessed at each study visit and the 1-week post-disclosure phone call by three items that have been used in prior work to assess worry in minors with a family history of cancer (Cappelli et al. 2005; Lerman et al. 1994). Three aspects of worry were assessed: extent (“How concerned are you about your chance of getting melanoma?”), frequency (“How often do you worry about getting melanoma?”), and intrusion (“How much do worries about melanoma affect the way you feel from day to day?”). All items were rated on 4-point Likert scales, with higher values indicating greater worry. Responses were averaged for analyses, with variable reliability across assessments (αs = .63–.83).

Structured Interviews

At both 1 month and 1 year post-disclosure, participants and their mothers were individually interviewed using a structured protocol that addressed multiple emotional and behavioral consequences of genetic counseling. Sections regarding children’s feelings about melanoma risk (see Table 1 for interview questions) and mothers’ perceptions of the positive and negative consequences of their children having undergone genetic counseling and testing were analyzed in the present study. Questions about perceived consequences of genetic counseling were asked to mothers at the 1-year interview. These questions were first framed generally (e.g., “How do you feel now about your decision for your child(ren) to undergo testing?”) and then specifically probed both positive and negative aspects of genetic testing (e.g., “Were there any unexpected or surprising positive or negative consequences of participating in risk counseling and genetic testing?”). Using a coding scheme developed for this project, responses were independently coded by two coders who achieved good inter-rater agreement, ranging from 82 to 100% within each category.

Table 1.

Minors’ attitudes and feelings about melanoma risk reported by carrier and noncarrier respondents and their mothers 1 month and 1 year following genetic counseling and test reporting

| 1 month

|

1 year

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier % (n = 9) |

Noncarrier % (n = 9) |

Total % (N = 18) |

Carrier % (n = 9) |

Noncarrier % (n = 9) |

Total % (N = 18) |

||

| Minor-reported | Feelings prior to testinga | ||||||

| Did you think about melanoma before this study? | |||||||

| How did it make you feel? | |||||||

| I did not think about melanoma before this study | 66.6 | 55.5 | 61.1 | – | – | – | |

| I was aware of the risk but it did not bother me | 22.2 | 33.3 | 27.7 | – | – | – | |

| I thought about it and it worried me (degree not specified) | 11.1 | 0.0 | 5.6 | – | – | – | |

| I was aware of the risk and a little worried | 0.0 | 11.1 | 5.6 | – | – | – | |

| I was aware of the risk and very worried | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – | – | – | |

| Change in feelings following testinga | |||||||

| Did the counseling session change how you felt about getting melanoma? Now, after getting risk counseling, are you more or less scared about getting melanoma? | |||||||

| Now, after getting risk counseling, are you more or less scared about getting melanoma? | |||||||

| Risk counseling made me less worried/scared about getting melanoma | 55.5 | 44.4 | 50.0 | – | – | – | |

| Risk counseling made me less worried/scared because I know melanoma is treatable | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.1 | – | – | – | |

| Risk counseling made me less worried/scared because I know I can protect my skin and reduce risk | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.1 | – | – | – | |

| No change in feelings | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | – | – | – | |

| Risk counseling made me more scared about getting melanoma | 11.1 | 22.2 | 16.6 | – | – | – | |

| Current feelings | |||||||

| How do you feel now when you think about getting melanoma? Are you worried/concerned about getting melanoma? | |||||||

| I do not think/worry about getting melanoma | 66.6 | 44.4 | 55.5 | 55.5 | 33.3 | 44.4 | |

| I think/worry about getting melanoma a little | 11.1 | 55.5 | 33.3 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 44.4 | |

| I think/worry about getting melanoma (degree not specified) | 11.1 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 11.1 | |

| I think/worry about getting melanoma a lot | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| I am not sure | 11.1 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Parent-reported | Change in feelings following testing | ||||||

| Did the counseling session change how your child felt about getting melanoma? Now, after getting risk counseling, is your child more or less scared about getting melanoma? | |||||||

| Risk counseling made my child less worried/scared about getting melanoma | 0.0 | 77.8 | 38.9 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 50.0 | |

| Risk counseling made my child less worried/scared because he/she knows melanoma is treatable | 0.0 | 33.3 | 16.7 | 33.3 | 22.2 | 27.8 | |

| Risk counseling made my child less worried/scared because he/she knows he/she can protect their skin and reduce risk | 0.0 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 27.8 | |

| No change in feelings | 66.7 | 22.2 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 33.3 | 38.9 | |

| Risk counseling made my child more scared about getting melanoma | 33.3 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 11.1 | |

| Minor-reported | Do you think you could get melanoma when you are older? Why or why not?a | ||||||

| Yes | 100.0 | 55.5 | 72.2 | – | – | – | |

| Yes, because I have a genetic risk | 22.2 | 11.1 | 16.6 | – | – | – | |

| Yes, because people in my family have had it | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.1 | – | – | – | |

| Yes, because of high sun exposure | 33.3 | 11.1 | 22.2 | – | – | – | |

| I could develop it because anyone can | 22.2 | 22.2 | 22.2 | – | – | – | |

| I am not sure/maybe | 0.0 | 33.3 | 22.2 | – | – | – | |

| No | 0.0 | 11.1 | 5.6 | – | – | – | |

Italicized codes were used to describe additional detail provided by participants in describing their response. Because some participants provided more than one additional elaboration and some did not elaborate on responses, the sum of percentages for these categories may not be equivalent to the sample size

This question was only asked at the 1-month interview

Analysis Plan for Quantitative Measures

Analyses examined changes in behavior and distress over the short- and long-term following counseling and test disclosure, as well as whether carriers and noncarriers reported different outcomes. The type of analysis performed depended on whether the outcome was on a continuous scale (e.g., degree of worry) or was dichotomous (e.g., no monthly screening vs. one or more exams). Outcomes with continuous scales (number of sunburns, cancer worry, depression, and anxiety) were analyzed by a series of two (group: carrier vs. noncarrier) by three (time: baseline, 1 month post-disclosure, and 1 year post-disclosure) mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Short-term change in distress was separately evaluated in ANOVAs with two timepoints (baseline, 1-week follow-up) utilizing data from the 15 participants who completed the 1-week follow-up phone survey. For dichotomous measures of sun protection and SSE adherence, a series of McNemar tests was run to test effects over time: these analyses compared the proportion reporting adherence at baseline to the proportion reporting adherence at 1 month and (in a separate analysis) 1 year. Additionally, for these variables, Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess differences between carriers and noncarriers at each assessment. Consistent with the prediction that behaviors would improve over time and that carriers would be more adherent, one-tailed significance tests are reported.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The mean age of participants was 12.4 (SD = 1.9). Ten participants (55.6%) were male. All were non-Hispanic whites. The median household income among participating families was $90,000 to $99,000. Half (n = 9) tested positive for the p16 mutation and half tested negative. Gender was unequally distributed by mutation status; males comprised 77.8% of carriers but only 33.3% of noncarriers.

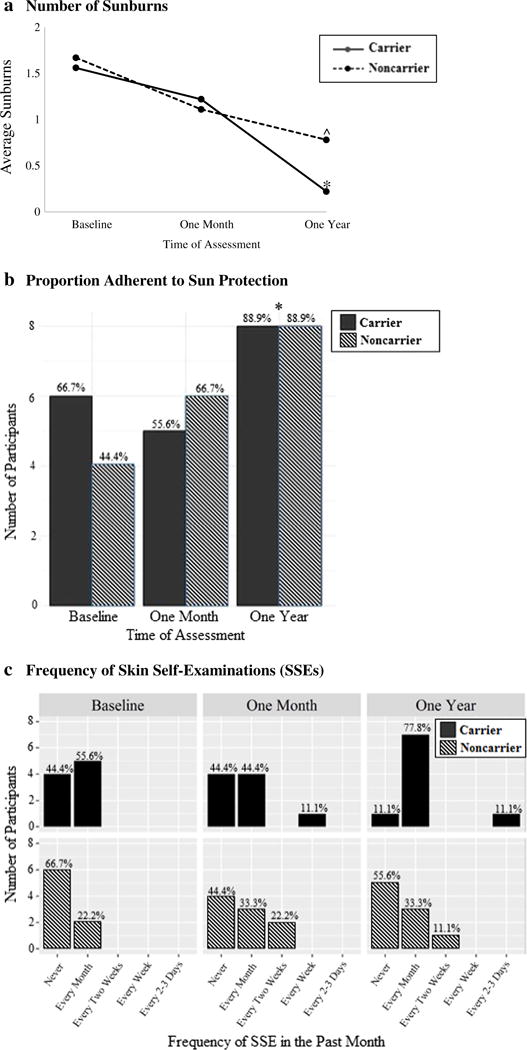

Sunburns

Figure 2(a) displays the average number of sunburns reported in the past month in each group over time. At baseline, participants reported an average of 1.61 (SD = 1.54) sunburns in the past month. As shown in Fig. 2(a), the number of sunburns decreased significantly over time (F(2,32) = 6.20, p = .005); at 1 year, mean sunburns (M = 0.50, SD = .86) had decreased over 50%. This decrease in sunburns was reported equally by both carriers and noncarriers, with no differences between the groups at any assessment (p > .05).

Fig. 2.

Sunburns, sun protection, and SSE frequency in past month reported by carrier and noncarrier minors at baseline, 1 month, and 1 year following genetic counseling and test disclosure. Notes. Percentages are calculated within each group at each timepoint. At baseline, one noncarrier did not provide a response to the SSE frequency question. Sun protection involved doing at least one behavior (using sunscreen, protective clothing, or a hat, seeking shade, avoiding peak exposure) often or always. ^ denotes changes marginally significant change from baseline (p < .10). * denotes changes significant change from baseline (p < .05)

Sun Protection

At baseline over half (55.6%) of minors already reported adherence to one or more methods of sun protection. As shown in Fig. 2(b), this proportion remained consistent at 1 month (61%, p > .05) and significantly increased to 88.9% at 1 year (p = .04). Sun protection adherence did not vary between carriers and noncarriers (ps > .05).

Skin Self-Examinations

As shown in Fig. 2(c), there was a trend toward a greater proportion of minors reporting monthly SSE performance over time, from 41.1% at baseline to 66.7% at 1 year. SSE adherence did not significantly vary between carriers and non-carriers at baseline or 1 month (ps > .05), but at 1 year, a marginally greater proportion of carriers reported monthly SSE adherence (88.9% of carriers vs. 44.4% of noncarriers, p = .07). Among minors who reported performing SSEs at the 1-year follow-up, most were doing so at the recommended rate of once per month, with just one carrier screening at a very frequent rate of every 2–3 days.

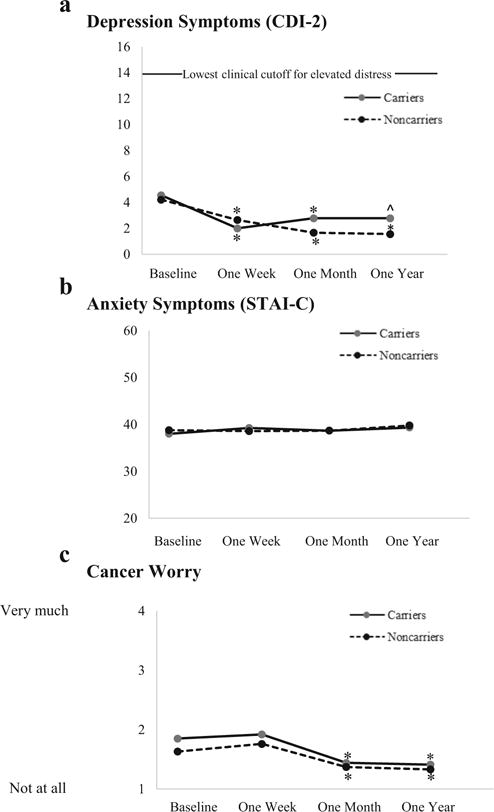

Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

Figure 3 displays mean values for depression and anxiety among carriers and noncarriers over time. No participant approached clinical cutoffs for depression at any point throughout the study and no differences between carriers and noncarriers were observed (ps > .05). At baseline, depressive symptoms were low (M = 4.39, SD = 3.18) and decreased significantly both 1 month (M = 2.22, SD = 2.71) and 1 year (M = 2.17, SD = 2.09) following counseling (F(2,32) = 11.75, p < .01). Similarly, anxiety scores were low at baseline (M = 38.39, SD = 2.48) and did not differ over time or between carriers and noncarriers (ps > .05). Analyses of short-term psychological outcomes at 1 week similarly indicated a lack of distress in either group following genetic test reporting and counseling; instead, there was a significant decrease from baseline for depression for both groups (M = 2.47, SD = 2.26; F(1,13) = 8.44, p = .012) and no change in either group for anxiety (ps > .05).

Fig. 3.

Psychological distress reported in carrier and noncarrier minors receiving melanoma genetic test results prior to 1 week, 1 month, and 1 year following genetic counseling and test disclosure. Notes. Means at the 1-week post-counseling visit reflect the subset who completed that assessment (n = 15); other means reflect full sample (n = 18). For depression (but not anxiety or cancer worry), clinical cutoffs for elevated distress are available; among those 12 or younger, cutoffs for elevated depressive symptoms are 14 for females and 17 for males, and among those older than 12, cutoffs are 20 for females and 16 for males. ^ denotes marginally significant decrease from baseline (p < .10). * denotes significant decrease from baseline (p < .05)

Cancer Worry

As shown in Fig. 3(c), among both carriers and noncarriers, worry decreased over time (F(2,32) = 4.38, p = .021). At baseline, participants’ reported worry (M = 1.74, SD = .63) was low, with worry significantly decreasing at 1 month (M = 1.41, SD = .45, p < .05) and remaining low at 1 year (M = 1.37, SD = .38) following test reporting. Cancer worry did not differ between carriers and noncarriers overall or at any assessment (ps > .05). The short-term analysis of cancer worry at 1 week showed no change over time and no difference between carriers and noncarriers (ps > .05).

Minors’ Attitudes and Feelings About Melanoma Risk Following Genetic Testing: Qualitative Findings

Responses to interview questions regarding minors’ feelings about melanoma were analyzed to provide additional perspectives from participants on whether genetic counseling led to increased distress and to explore additional emotional responses to genetic testing that may not have been captured by quantitative measures. As shown in Table 1, most children (61.1%) reported that they did not think about their melanoma risk prior to undergoing genetic testing and counseling, and only two (11.1%) reported being worried before undergoing the pre-test counseling session: “Before I came, I was kinda a little scared to find out the answer. . . but umm I learned from the first session that it’s not that big of a deal. . . if I did have the gene I’d just be more cautious” (male carrier, age 11). Following test reporting and counseling, children also generally reported that they did not think or worry about getting melanoma (61.1%), regardless of testing status. Among children who reported that they were less worried following testing (50.0%), some elaborated that this was because they learned that melanoma was treatable (11.1%) or that they could take steps to protect their skin (11.1%). For instance, one child indicated she was less worried because she “knew it was a type of cancer that umm mostly can be stopped if you find it at the right time” (female noncarrier, age 14).

While most children either reported a decrease or no change in worry 1 month following testing, three children (16.6%) reported being more scared of getting melanoma. For these children, their degree of fear was not described in extreme terms—for instance, a carrier who reported now being more scared said, “probably more scared just not, not by much but probably more scared ’cause I didn’t know how dangerous it was” (male carrier, age 14).

Child reports of attitudes and feelings at 1 year, as well as parents’ reports of their child’s feelings, corroborated these findings. At 1 year, more minors reported thinking or worrying about melanoma (61.1 vs. 33.3%), but none reported being extremely scared or worried about their risk. At both 1 month and 1 year, parents most commonly noted that their child(ren)’s feelings about melanoma had not changed since receiving genetic counseling.

These qualitative findings indicate that while minors were not distressed following genetic counseling, they nevertheless seemed to understand their high-risk status. In the 1-month interviews, most minors (72.2%) reported that they believed they could get melanoma later in life. Among carriers, 100% believed that they could get melanoma. Minor carriers and noncarriers described several reasons they believed they could get melanoma, including both genetic and environmental factors. Consistent with counseling that even those who test negative could develop melanoma based on personal characteristics or behavior in the sun, only one noncarrier (11.1%) did not believe that he or she could develop melanoma.

Mothers’ Perspectives on the Positive and Negative Consequences of Melanoma Genetic Testing and Counseling: Qualitative Findings

Regardless of their child(ren)’s mutation status, mothers unanimously reported positive evaluations of their decision to have their child undergo genetic testing (see Table 2). Some parents elaborated on the emotional benefits of undergoing testing. For instance, four of eight mothers with a noncarrier child (50.0%) reported experiencing relief after learning that their child(ren) did not have the p16 mutation. All mothers reported one or more ways in which genetic counseling had an informational benefit of raising their child(ren)’s awareness of risk status or melanoma prevention. Mothers also commonly mentioned ways in which the genetic counseling had influenced the behavior of their children. The majority (81.8%) mentioned improvements in their child(ren)’s sun protection behaviors. Several added that following genetic counseling, their child(ren) now did not argue with them about sun protection (18.2%) or had begun taking independent responsibility for their sun protection (45.4%).

Table 2.

Mothers’ perspectives on the positive and negative consequences of genetic testing for their minor children reported at 1-year follow-up

| Mutation status of child(ren) in each family

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier % (n = 3) |

Both carrier and noncarrier % (n = 4) |

Non-carrier % (n = 4) |

All mothers % (N = 11) |

Qualitative example | |

| Overall, taking all things into consideration, how do you feel now about your decision for your child(ren) to participate in risk counseling? | |||||

| Positive/right decision | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | “I’m glad we did it.” |

| Negative/wrong decision | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | N/A |

| Emotional benefitsa | |||||

| Peace of mind/relief experienced by parent (if noncarrier child) | 0.0 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 36.4 | “It gives me a peace of mind for the one that was negative” |

| Peace of mind/relief experienced by child (if noncarrier child) | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | “For him, knowing he didn’t have it was almost a relief and calm” |

| Informational benefits (increased knowledge, education, or awareness)a | |||||

| Awareness of risk/genetic status is a general benefit and/or especially beneficial at early age | 66.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 90.9 | “She’s lucky to find out this early” |

| Increase in child(ren)’s awareness of melanoma and prevention behaviors | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | “Have them kind of realize that okay, yeah, I need to be careful” |

| Increase in parent’s own awareness of melanoma and prevention behaviors | 33.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 81.8 | “Just knowing that your kids have a risk would heighten your awareness of what they’re doing and when, you know, when they’re going out in the sun” |

| Improved adherence to melanoma prevention recommendationsa | |||||

| Increase in sun protection of child | 100.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 81.8 | “I think it just makes us more prone to be protected in the sun” |

| Decrease in familial conflict about sun protection | 0.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 18.2 | “They don’t fight with me about sunscreen anymore” |

| Increase in child taking responsibility and initiating sun protection behavior | 33.3 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 45.5 | “I don’t have to, um, remind them as often. They’ve taken it on themselves.” |

| Increase in skin checks for child | 66.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 | “We’ve got her an appointment already with a dermatologist to do skin checks” |

| Negative consequencesa | |||||

| Potential for increased anxiety/worry in parent | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 9.1 | “Some of my family members that I know have come in and done the testing, they’re worriers and I feel like this has escalated their worry for their children” |

| Potential for increased anxiety/worry in child | 33.3 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 27.3 | “I think that if you had a child that worries a lot, it might cause them some more” |

| Lack of prioritization of sun protection in noncarrier child | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | “Since he’s negative he thinks he can do whatever he wants now” |

| Complaints about research participation reported by child | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | “They just have to answer tons of questions, and it takes a long time. That was their one question ‘Do we have to answer more questions?’” |

| Time commitment/inconvenience of participating in counseling | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | “Just a long drive, but that’s about it.” |

| Cost of obtaining genetic testing outside of research participation is high | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | “So if you aren’t in a study, I know when I did it for myself it was way expensive. There’s a huge price tag to it But that’s the only downside.” |

Responses to all open-ended questions were considered as a set and coded using for the presence or absence of each of these subcategories (see Method)

Despite their overall positive feelings about genetic counseling, about half (54.5%) of mothers brought up at least one potential negative consequence of melanoma genetic testing. Three mothers (27.3%) expressed that, despite their own positive experiences, they felt it was possible that undergoing genetic testing could heighten anxiety and worry among other parents and children prone to worry. Additional negative consequences mentioned included noncarrier children failing to prioritize sun protection, complaints about participation in research activities (i.e., completing questionnaires), the time commitment of attending counseling, and the cost of undergoing a genetic test on one’s own (i.e., outside of a research study).

Discussion

Genetic test reporting and counseling for melanoma risk have the potential to motivate minors to engage in protective and screening practices, which may reduce the likelihood and severity of later illness (Bibbins-Domingo et al. 2016). In the present study, among 18 children who underwent genetic testing for the p16 mutation, results provided support for the behavioral benefits of genetic testing and counseling with no indication of elevated depression or anxiety at any assessment. Sunburns significantly decreased in the year following counseling among both carriers and noncarriers, while the proportion of participants reporting adherence to sun protection significantly improved. Analyses consistently indicated a lack of distress among minors receiving melanoma genetic test results and counseling both during the month following counseling and 1 year later. Thus, findings from this initial study suggest that genetic test disclosure and accompanying counseling can lead to positive behavioral improvements without inducing distress, even in the short term.

An important consideration in evaluating the clinical utility of providing genetic test results for p16 and other predictive mutations for familial cancer is whether doing so would elevate distress. To address this question, we used well-validated measures of depression and anxiety, cancer-specific assessments of worry, and detailed interviews with children and parents. Further, we conducted a distress screening phone call 1 week following counseling and test reporting. The distress screening phone calls indicated that reported distress was low even during the initial days following test disclosure. Reported depressive symptoms and cancer worry were low throughout the study and decreased following counseling and test reporting. It is possible that the apparent decrease in depressive symptoms and worry from baseline to 1 week reflected mild elevations in depression and worry in anticipation of the clinic visit and the demands of study participation (including a blood draw, which they learned about prior to the baseline visit). Reported anxiety symptoms were low and remained low throughout the study. The stability observed in anxiety may be attributable to our use of a trait inventory. The use of an anxiety measure that defined a specific time period for responses (e.g., “past week”) would likely have improved the sensitivity of these assessments. However, it is important to note that depressive symptoms, which were measured with reference to the past week, did not approach clinical cutoffs for any participant at any assessment.

The behavioral improvements reported in the current study are noteworthy because sun protection is often inadequate in children and childhood sun exposure is a risk factor for developing melanoma (Gandini et al. 2005; Whiteman et al. 2001). Even in this sample from high-risk families, sun protection was often inadequate at baseline. The majority of participants reported sustaining a sunburn in the past month and only about half were performing at least one sun protection method consistently. This finding was somewhat surprising as, in most participating families, a parent had received extensive education on sun protection through his or her own genetic counseling session. However, these findings are consistent with prior research showing that minors from families with a melanoma history perform protective behaviors at similar rates to the general population (Geller et al. 2007; Glenn et al. 2015).

That behavioral improvements were reported both among carriers and noncarriers suggests that the education provided during the counseling session may have itself contributed to behavior change. While improvement in sun protection and sunburn rates did not significantly differ between carriers and noncarriers, carriers tended to report greater rates of performing monthly SSEs at the 1-year follow-up than noncarriers. While this finding may indicate that the positive test result enhanced motivation to perform SSEs, it also may be, in part, attributable to recommendations presented during counseling that carriers receive yearly total body skin examinations from a medical provider. Although this study was designed to evaluate how minors respond to disclosure of genetic test results, provision of education accompanying this disclosure is an indispensable element for promoting positive outcomes, and the study design does not allow us to differentiate the effects of genetic test reporting from those of the accompanying education about genetic risks and their management. For the present study, the counseling sessions were developed by two experienced certified genetic counselors who designed materials that were appropriate for younger participants, enhanced engagement through true/false questions and other prompts, and promoted an understanding of the link between sun exposure and melanoma risk. Although our research in adults indicates that p16 genetic test reporting and counseling promote informational and motivational benefits beyond equivalent family history-based counseling alone (Aspinwall et al. 2017), additional research is needed to determine whether these findings extend to minors.

One year following testing, participants’ mothers unanimously provided positive evaluations of the decision for their child to undergo genetic testing and provided important additional insights regarding the costs and benefits of genetic testing. Several mothers noted that their children were now more independently engaged in sun protection behaviors. While mothers did not commonly mention negative aspects of testing, several noted concerns that their children would be worried or that other more worry-prone children would not respond well to genetic counseling. In a larger sample, it will be important to further investigate how individual differences among minors, and parental perspectives on these differences, should be considered in making decisions about the psychological impact of testing.

In sum, this study addressed the critical question of whether genetic testing for disease predisposition among minors may improve disease control or prevention behaviors without inducing distress. In contrast to most hereditary cancer syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 interventions, for which risk reduction primarily involves screenings and procedures undertaken in a medical setting, risk reduction strategies for melanoma are largely under the minor’s direct control, and thus, it is important to evaluate whether test reporting for melanoma risk changes minors’ own behaviors. Our results support the clinical utility of genetic testing for p16 among minors, as genetic test reporting and counseling promoted preventive behaviors that could impact health in adulthood. Future research is needed to determine whether there are additional conditions for which genetic test disclosure may promote positive lifestyle changes among minors. Further, it will be important to examine whether genetic test reporting motivates behavior change (and does so without inducing distress), when the recommended behaviors or screenings are more intensive or burdensome to minors or their families.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, although the use of a repeated measures design provided greater power to detect effects than a group comparison at a single assessment, the small sample size of 18 participants from just 11 families nevertheless limited statistical power to test for between-group differences as well as moderation by demographic characteristics, such as age and gender. Second, these study results may not generalize to all minors from families with a known p16 mutation. In this study, a high percentage of minors came from high-income households. Also, gender was unequally distributed across groups, with more males tested being positive; thus, future study is needed to investigate whether our findings about how minors respond to positive genetic test results generalize to female carriers. Investigating the effect of gender on behavioral outcomes of melanoma genetic test reporting is important as previous research indicates differences in sun protection strategies between men and women (Buller et al. 2011; Geller et al. 2002; Haluza et al. 2016). Third, because we did not include a control group of children from melanoma-prone families known not to carry a p16 mutation, we are unable to conclude whether genetic testing had a unique benefit compared to counseling based on family history alone (see Taber et al. 2015 and Aspinwall et al. 2017, for discussion). Finally, the small sample size and other limitations described in the supplementary Reflectance Spectroscopy Analyses (such as the need to statistically control for skin type in assessments of tanning) precluded use of more objective measures of sun exposure, but the inclusion of these measures would provide an important objective complement to the children’s and parents’ reports of sun protection behavior described here.

Practical Implications

These findings support the clinical utility of genetic testing and counseling for melanoma risk among minors from families with known familial predisposition mutations. Parents and genetic counselors should continue to monitor for the presence of distress throughout the counseling session and the months following test disclosure, as increased distress, though not observed here on well-validated measures, was noted as a possibility by several mothers.

Research Recommendations

Additional research is needed to confirm these findings and better understand changes in sun exposure patterns and protection methods following p16 counseling and testing. This research may also explore ways to further improve adherence to recommended protective and screening behaviors. For instance, participants may benefit from counseling sessions that are tailored to their developmental level or other characteristics, such as baseline understanding of melanoma and genetics-related concepts (Wu et al. 2016a). Participants may also benefit from interventions designed to improve family communication about melanoma (Wu et al. 2016b)—a topic which is sometimes avoided in family conversations in order to minimize fear (Hay et al. 2008). Likewise, future studies should examine risk communication and behavior among families in which children have undergone p16 testing, including families in which children received disparate results. Lastly, research is needed to determine whether improved sunprotective and screening behaviors are maintained over a longer term and whether and how these risk-reducing behaviors change as minors transition to adulthood.

Conclusions

Genetic counseling for melanoma risk provides not only information about risk but also important education that melanoma is preventable and treatable. This small initial study provides support for the clinical utility of genetic testing and counseling for melanoma risk among minors from families with known familial predisposition mutations. Following testing, participants—both carriers and noncarriers alike—reported decreases in sunburns and increases in sun protection. Importantly, psychological distress was low and remained so following genetic testing as assessed both by well-validated measures of depression and anxiety and qualitative accounts provided by minors and their mothers. While these initial results suggest a favorable risk-benefit ratio for melanoma genetic testing for minors, future studies with a larger sample, including a greater number of female carriers, are needed to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a pilot grant from the Cancer Control and Population Sciences Program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute. T.K.S., L.G.A., W.K., M.C., E.S., P.C., and S.A.L. were partially supported during the conduct of the study and/or preparation of the manuscript by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01 CA158322. During manuscript preparation, T.K.S. was supported by NIH/NCI training grant T32 CA193193. Y.P.W. was supported by the NIH/NCI career development grant K07CA196985 (Y.P.W.) and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation (HCF). P.C. was supported by NIH R01CA166710. Additional support for the study was provided by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI or the NIH. Support was also received from the HCF, the Tom C. Mathews, Jr. Familial Melanoma Research Clinic endowment, the Pedigree and Population Resource of Huntsman Cancer Institute, and the Utah Population Database. This research was supported by the Utah Cancer Registry, which is funded by contract N01-PC-35141 from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, with additional support from the Utah State Department of Health and the University of Utah. The authors acknowledge the use of the Genetic Counseling and Health Measurement and Survey Methods core facilities supported by the NIH through NCI Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA420-14 awarded to Huntsman Cancer Institute and additional support from the HCF. The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous participation of all the family members in this study, without whom this project would not have been possible. We thank Dixie Thompson, Lisa Reynolds, Tami Calder, Michelle Allred, Teresa Stone, and Matt Haskell for their contributions to the conduct of the study. We thank Maria-Renee Coldagelli for verifying protocol adherence of the genetic counseling sessions. We acknowledge Taylor Haskell, Rebecca Stoffel, Christopher Moss, Roger Edwards, Kayla Denter, Taryn Wicijowski, Hannah Longhurst, and Dexter Thomas for their assistance with recruitment and/or data collection. We also thank Jeffrey Yancey and Meredith Vehar in the patient and public education department of the Huntsman Cancer Institute for assessing the reading level of our questionnaires and revising items as appropriate, and Sandie Edwards for her assistance with questionnaire design.

Funding: The work of several authors (Drs. Stump, Aspinwall, Wu, Cassidy, and Leachman) was funded by the NIH. Dr. Leachman served on a Medical and Scientific Advisory Board for Myriad Genetics Laboratory, for which she received an honorarium. She has collaborated with Myriad on a project to validate an assay that is unrelated to the research reported here. Ms. Kohlmann has consulted for Myriad Genetics Laboratory in the past on unrelated projects and received a research grant from Myriad Genetics Laboratory to study the psychological and family communication outcomes of multigene panel testing. That work is unrelated to the research reported here. Ms. Champine has been compensated for serving on the Genetic Counseling Advisory Board for Invitae, which is a for-profit genetic testing laboratory. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Leachman served on a Medical and Scientific Advisory Board for Myriad Genetics Laboratory, for which she received an honorarium. She has collaborated with Myriad on a project to validate an assay that is unrelated to the research reported here.

Ms. Kohlmann has consulted for Myriad Genetics Laboratory in the past on unrelated projects and received a research grant from Myriad Genetics Laboratory to study the psychological and family communication outcomes of multigene panel testing. That work is unrelated to the research reported here.

Ms. Champine has been compensated for serving on the Genetic Counseling Advisory Board for Invitae, which is a for-profit genetic testing laboratory.

Dr. Stump, Dr., Aspinwall, Ms. Hauglid, Dr. Wu, Ms. Scott, and Dr. Cassidy declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material: The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-017-0185-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Aspinwall LG, Leaf SL, Dola ER, Kohlmann W, Leachman SA. CDKN2A/p16 genetic test reporting improves early detection intentions and practices in high-risk melanoma families. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17(6):1510–1519. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Stump TK, Taber JM, Drummond D, Kohlmann W, Champine M, Leachman SA. Genetic test reporting of CDKN2A provides informational and motivational benefits for managing melanoma risk. Transl Behav Med. 2017 doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx011. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taber JM, Kohlmann W, Leaf SL, Leachman SA. Unaffected family members report improvements in daily routine sun protection 2 years following melanoma genetic testing. Genetics in Medicine. 2014;16(11):846–853. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taber JM, Leaf SL, Kohlmann W, Leachman SA. Genetic testing for hereditary melanoma and pancreatic cancer: a longitudinal study of psychological outcome. Psychooncology. 2013a;22(2):276–289. doi: 10.1002/pon.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taber JM, Leaf SL, Kohlmann W, Leachman SA. Melanoma genetic counseling and test reporting improve screening adherence among unaffected carriers 2 years later. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2013b;22(10):1687–1697. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Orlow I, Hummer AJ, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, Marrett LD, et al. Lifetime risk of melanoma in CDKN2A mutation carriers in a population-based sample. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(20):1507–1515. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenmar M, Hansson J, Brandberg Y. Family members’ perceptions of genetic testing for malignant melanoma—a prospective interview study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2009;13(2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Ebell M, Epling JW, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(4):429–435. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DT, Demenais F, Goldstein AM, Bergman W, Bishop JN, Bressac-de Paillerets B, et al. Geographical variation in the penetrance of CDKN2A mutations for melanoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94(12):894–903. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.12.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borry P, Howard HC, Senecal K, Avard D. Health-related direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a review of companies’ policies with regard to genetic testing in minors. Familial Cancer. 2010;9(1):51–59. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, Berkman BE, Bombard Y, Holm IA, et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2015;97(1):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi ML, Gagel RF, Angeli A, Bilezikian JP, Beck-Peccoz P, Bordi C, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of MEN type 1 and type 2. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(12):5658–5671. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller DB, Cokkinides V, Hall HI, Hartman AM, Saraiya M, Miller E, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: review from national surveys and case studies of 3 states. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;65(5 Suppl 1):S114–S123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke W, Daly M, Garber J, Botkin J, Kahn MJE, Lynch P, et al. Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer: II. BRCA1 and BRCA2. JAMA. 1997;277:997–1003. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540360065034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli M, Verma S, Korneluk Y, Hunter A, Tomiak E, Allanson J, et al. Psychological and genetic counseling implications for adolescent daughters of mothers with breast cancer. Clinical Genetics. 2005;67(6):481–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Glanz K, Albano J, Ward E, Thun M. Trends in sunburns, sun protection practices, and attitudes toward sun exposure protection and tanning among US adolescents, 1998–2004. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):853–864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadlani C, Orlow SJ. Planning for a brighter future: a review of sun protection and barriers to behavioral change in children and adolescents. Dermatology Online Journal. 2008;14(9):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini P, Picconi O, Boyle P, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(1):45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AC, Colditz G, Oliveria S, Emmons K, Jorgensen C, Aweh GN, et al. Use of sunscreen, sunburning rates, and tanning bed use among more than 10 000 US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1009–1014. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AC, Swetter SM, Brooks K, Demierre MF, Yaroch AL. Screening, early detection, and trends for melanoma: current status (2000–2006) and future directions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007;57(4):555–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.032. quiz 573-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Yaroch AL, Dancel M, Saraiya M, Crane LA, Buller DB, et al. Measures of sun exposure and sun protection practices for behavioral and epidemiologic research. Archives of Dermatology. 2008;144(2):217–222. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn BA, Lin T, Chang LC, Okada A, Wong WK, Glanz K, et al. Sun protection practices and sun exposure among children with a parental history of melanoma. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2015;24(1):169–177. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Half E, Bercovich D, Rozen P. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2009;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluza D, Simic S, Holtge J, Cervinka R, Moshammer H. Gender aspects of recreational sun-protective behavior: results of a representative, population-based survey among Austrian residents. Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 2016;32(1):11–21. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay J, Shuk E, Brady MS, Berwick M, Ostroff J, Halpern A. Family communication after melanoma diagnosis. Archives of Dermatology. 2008;144(4):553–554. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasparian NA, Meiser B, Butow PN, Simpson JM, Mann GJ. Genetic testing for melanoma risk: a prospective cohort study of uptake and outcomes among Australian families. Genetics in Medicine. 2009;11(4):265–278. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181993175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory 2™(CDI 2) North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Daly M, Masny A, Balshem A. Attitudes about genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1994;12(4):843–850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Edwards C. Preliminary test manual for the State-trait Anxiety Inventory for Children: (“How-I-feel questionnaire”) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Taber JM, Aspinwall LG, Kohlmann W, Dow R, Leachman SA. Parental preferences for CDKN2A/p16 testing of minors. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12(12):823–838. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f87278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber JM, Aspinwall LG, Stump TK, Kohlmann W, Champine M, Leachman SA. Genetic test reporting enhances understanding of risk information and acceptance of prevention recommendations compared to family history-based counseling alone. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;38(5):740–753. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9648-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UV Index: Annual Time Series, 2012. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/stratosphere/uv_index/uv_annual.shtml.

- Whiteman DC, Whiteman CA, Green AC. Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes & Control. 2001;12(1):69–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1008980919928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YP, Aspinwall LG, Michaelis TC, Stump T, Kohlmann WG, Leachman SA. Discussion of photoprotection, screening, and risk behaviors with children and grandchildren after melanoma genetic testing. Journal of Community Genetics. 2016a;7(1):21–31. doi: 10.1007/s12687-015-0243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YP, Aspinwall LG, Nagelhout E, Kohlmann W, Kaphingst KA, Homburger S, et al. Development of an educational program integrating concepts of genetic risk and preventive strategies for children with a family history of melanoma. Journal of Cancer Education. 2016b doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.