Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review is to summarize the prevalence and clinical implications of the isolated anti-HBc serologic profile in HIV-infected individuals. We seek to highlight the particular importance of HBV reactivation in the setting of HCV therapy and describe an approach to management.

Recent Findings

The isolated anti-HBc pattern, a profile that most often indicates past exposure to HBV with waning anti-HBs immunity, is found commonly in HIV infected individuals, particularly those with HCV. Some large cohort studies demonstrate an association with advanced liver disease, while others do not. Conversely, meta-analyses have found an association between occult HBV infection (a component of the isolated anti-HBc pattern) and advanced liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-uninfected individuals. In HIV uninfected individuals with anti-HBc positivity, HBV reactivation has been reported in patients receiving HCV therapy. This phenomenon is likely the result of disinhibition of HBV with HCV eradication.

Summary

In HIV infected patients, the long-term liver outcomes associated with the isolated anti-HBc pattern remain to be fully elucidated, supporting the need for large cohort studies with longitudinal follow-up. HBV reactivation during HCV DAA therapy has been well described in HIV uninfected cohorts and can inform algorithms for the screening and management of the isolated anti-HBc pattern in this population.

Keywords: DAA, HCV treatment, isolated anti-HBc, occult HBV, HIV/HCV, HIV infection

Introduction

The isolated hepatitis B core antibody serologic profile, defined as a positive anti-HBc with negative HBsAg and anti-HBs, occurs in up to 31% of HIV coinfected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) [1]. Isolated hepatitis B core antibodies (anti-HBc) in the absence of HBsAg and anti-HBs pose challenges in interpretation and management for providers. Understanding the management of the isolated anti-HBc profile in the context of HBV prevention and HCV therapy is important given the ramifications for HBV susceptibility and HBV reactivation. The purpose of this review is to examine the prevalence, clinical implications, and management of the isolated anti-HBc profile, with special attention to direct-acting antiviral therapy for patients with chronic HCV infection.

Hepatitis B Virus Life-Cycle

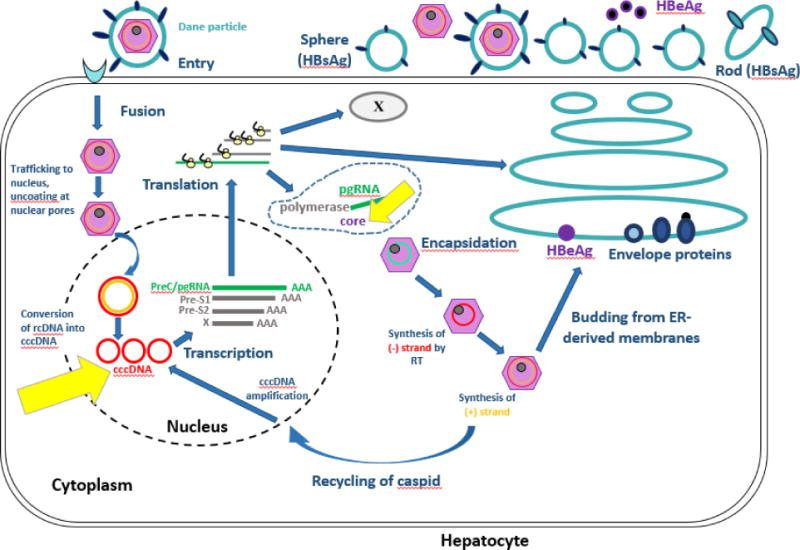

Hepatitis B virus establishes itself in chronic infection by way of dynamic processes involving viral and host immunity defenses. (See Figure 1) Attachment entry of the HBV virus requires interaction between HBsAg and hepatocyte surface proteins. HBV relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) is converted to covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), which serves as a transcriptional template for subsequent viral mRNA production and pregenomic RNA (pgRNA). This matures into nucleocapsid with viral polymerase, for viral propagation in the forms of virions outside the hepatocyte, or return to the nucleus as cccDNA [2]. The persistence of cccDNA despite effective inhibition of HBV viral polymerase through nucleos(t)ide analogues is the key reason why cure of HBV remains elusive [3], as it provides a transcriptional reservoir for continued replication of virus [4]. The presence of cccDNA also leads to production of the core antigen (CrAg) to which antibody is formed in the form of anti-HBc. This explains why anti-HBc is present in acute, chronic, and resolved infection.

Figure 1. Hepatitis B Virus Life Cycle.

Figure 1 depicts the HBV lifecycle. Yellow arrows highlight cccDNA and the production of the core protein, demonstrating that the production of core protein occurs independent of HBV viral replication and as a direct result of the presence of the transcriptionally active reservoir of cccDNA

Modified from: Ait-goughoulte Malika, Lucifora J, Zoulim F, Durantel D. Innate Antiviral Immune Responses to Hepatitis B Virus. Viruses. 2010;2(7):1394-1410. doi:10.3390/v2071394. Modified with permission from Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 3.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/legalcode.

Hepatitis B Serologic Markers and Definition of the Isolated anti-HBc Serologic Profile

As hepatitis B infection progresses or resolves, clinical states of infection are reflected in HBV serologies. The presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) marks active acute or chronic HBV infection. Suboptimal immune responses due to host factors such as age at time of exposure, or advanced immunosuppression, increase the risk for chronic HBV and subsequent complications. Due to mechanisms of immune control, and the presence of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) that persists lifelong after HBV exposure, HBV reactivation is always possible even following immunologic recovery and clearance of HBsAg. During chronic infection, markers for HBeAg and anti-HBe may be helpful in delineating phases of chronic HBV infection. Hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) may be seen in acute or chronic infection, and also may persist for life after immunity is developed (resolved infection). As infection resolves hepatitis B surface antibody develops (anti-HBs). Anti-HBs, in the absence of HBsAg or anti-HBc, denotes immunity from hepatitis B vaccination. The isolated anti-HBc profile is defined as the presence of anti-HBc in the absence of HBsAg and anti-HBs. Interpretations of hepatitis B serologies are listed below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Interpretation of Hepatitis B Serologies

| HBsAg | Anti-HBc IgM | Anti-HBc | Anti-HBs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | --- | Negative | Negative | Susceptible |

| Negative | --- | Positive | Positive | Immune Due to Previous Infection |

| Negative | --- | Negative | Positive | Immune Due to Hepatitis B Vaccination |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | Acute Infection |

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Chronic Infection |

| Negative | --- | Positive | Negative | Isolated anti-HBc Pattern:

|

Definitions: HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; Anti-HBc IgM: antibody to Hepatitis B core antigen; Anti-HBs: antibody to HBsAg

Interpretation of the isolated anti-HBc pattern (Table 1)

Several potential clinical interpretations of isolated anti-HBc are considered in the evaluation of HBV serologies, including 1) resolved HBV infection with very low levels of anti-HBs undetectable with current assays, due to waning immunity, or 2) occult HBV, the presence of HBV viremia, often a result of mutant HBsAg, which is not detected on standard serological testing for HBV 3) the window period of acute HBV infection where immune complexes precipitate from HBsAg and HBsAb, thereby creating an apparent isolated anti-HBc pattern which serologically evolves with time and 4) false positive tests, which may be found in low prevalence populations or artificial circumstances related to assay quality and technical preparation. The most common reason for the isolated anti-HBc pattern is likely waning immunity. This is best demonstrated by an HBV serologic study conducted in the MACS cohort, a large cohort of HIV infected and uninfected participants. In this cohort, which assessed change in HBV serologies over time, the anti-HBc pattern was consistently positive in ~80% of participants. The most common transitions of the isolated anti-HBc profile were to gain or lose anti-HBs, suggesting that the low or intermittently undetectable anti-HBs represented resolved HBV infection, as opposed to occult HBV viremia [5]. One limitation to this study was that HBV viremia was not assessed, but other studies (see below) have reported low rates of occult HBV viremia in those with the isolated anti-HBc profile [6].

Mechanisms of the Isolated anti-HBc Pattern

Hepatitis B virus persists as cccDNA following exposure. Persistent HBV infection with low or undetectable levels of HBV viremia in the setting of an isolated anti-HBc potentially involves methylation of HBV cccDNA within the hepatocyte[7], thereby downregulating DNA and subsequent mRNA expression, with subsequent quiescence of HBsAg production [8]. Other epigenetic factors such as downregulation of acetylation may also play important roles towards transcriptional suppression of cccDNA in hepatocytes to explain serological patterns noted in patients with the isolated anti-HBc profile.

Prevalence and Predictors of the anti-HBc serologic profile and occult HBV infection in HIV infection

Wide variation exists on the prevalence of isolated anti-HBc findings. In HIV+ cohorts, 17% to 40% of patients have been reported to have the isolated anti-HBc[1, 5, 6, 9–23], owing to similar routes of transmission for HIV and HBV. Predictors of the isolated anti-HBc pattern include HIV infection[5, 24, 25], HCV infection[5], and specifically HCV viremia[25], older age[24], IDU, multiple sexual partners, and elevated HIV RNA levels [25]. The isolated anti-HBc pattern is particularly common in HIV/HCV coinfection, likely due to shared routes of transmission and viral interplay (see below). Estimates of prevalence of isolated anti-HBc may be limited due to differences in geography, as well as sensitivities of different immunoassays used in each study. This is in contrast to HIV negative cohorts, where the prevalence of the isolated anti-HBc ranges from 5.3-31.6% [5, 14].

The definition of occult HBV varies across studies; some define occult HBV infection as HBV DNA positivity with HBsAg negativity, regardless of anti-HBc status, while other studies define occult HBV as HBV viremia only in the setting of the isolated anti-HBc profile. Several studies have assessed the prevalence of occult HBV infection among patients with HIV and isolated anti-HBc, which has been reported to range from 0.6% [11] – 2.5% noted in the BHOI study[9], to as high as >89.5% in a Swiss cohort study[23]. In the Women’s Interagency Cohort Study (WICS), 2% of women with HIV and a pattern of isolated HBcAb were found to have detectable HBV DNA [14]. Occult HBV viremia was associated with severe immunosuppression with CD4 <200 cells/mm3 in the WIHS cohort.

Association with Advanced Liver Disease and its Complications

The association with the isolated anti-HBc pattern and advanced liver disease is difficult to ascertain, in part, because studies have assessed the association of advanced liver disease with both the isolated anti-HBc pattern and occult HBV infection, which is a component of the isolated anti-HBc pattern but not its sole etiology. When assessing the isolated anti-HBc pattern overall, varying liver progression outcomes have been observed in HIV-infected cohorts (Table 2). One study in France of 344 HIV+ women suggested that the isolated anti-HBc pattern was not associated with accelerated liver progression over a median 9.5 years [25]. In contrast, a large American cross-sectional analysis in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) found that isolated anti-HBc in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection was associated with more advanced hepatic fibrosis, as defined by APRI and FIB-4 scores [1]. These differences may lie in differences in study design (cross-sectional vs longitudinal) and study populations as women are less likely to have liver disease progression, compared to men.

Table 2.

Prevalence of, and Association with, Liver Disease Outcomes in Patients with the Isolated Anti-HBc Serologic Profile and/or Occult HBV Infection in HIV-Infected Cohorts

| Cohort | Number of HIV + patients | Prevalence of Isolated Anti-HBc and/or occult HBV infection | Liver Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected | ||||

| HIV-infected, USA, VACS cohort, cross-sectional | 19,486 | Isolated anti-HBc: 1504 (12.3%) OBI not reported |

Isolated anti-HBc associated with advanced fibrosis (FIB-4, platelets) in HIV/HCV, when compared to resolved anti-HBs (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.20-2.28) | Bhattacharya JAIDS 2017 |

| HIV infected individuals, Spain, cross-sectional | 3,030 | Isolated anti-HBc: 202 (6.6%) OBI of anti-HBc: 5 (2.5%) |

No association with baseline elevated transaminases | Palacios HIV Clin Trials 2008 |

| HIV-infected HBsAg negative pregnant women, Thailand, PHPT-2 | 1682 | Isolated anti-HBc: 229 (13.6%) OBI of anti-HBc: 47 (2.8%) |

No association with HBV perinatal transmission | Khamduang CID 2013 |

| HIV-infected, USA, MACS Cohort, longitudinal | 1,169 | Isolated anti-HBc: 259 (22.2%) OBI not reported |

---------------------------------------------------------- | Witt Clin Infect Dis 2012 |

| HIV-infected, France, Aquitaine Cohort, cross-sectional | 1,123 | Isolated anti-HBc: 160 (14.2%) OBI of anti-HBc: 1 (0.63%) |

---------------------------------------------------------- | Neau CID 2005 |

| HIV-infected, South Africa, cross-sectional | 502 | Isolated anti-HBc: 53 (10.6%) OBI: 38/43 (88.4%) |

---------------------------------------------------------- | Firnhaber Int J Infect Dis 2009 |

| HIV-infected, India, cross-sectional | 441 | OBI: 28/441 (6.3%) | ---------------------------------------------------------- | Saha PLOS One 2017 |

| HIV-infected, USA, WIHS Cohort, cross-sectional | 400 with isolated anti-HBc | OBI of anti-HBc: 8 (2%) | No association between ALT levels and OBI status | Tsui Clin Infect Dis 2007 |

| HIV-infected, Ghana, cross-sectional | 385 | OBI: 35 (1%) | Increased proportion (65%) with elevated transaminases after ART initiation at 1 mos, but not 6,12 mos, compared to | Chadwick AIDS 2013 |

| HIV infected women, USA, WIHS cohort, longitudinal | 344 HIV/HCV median 9.5 yrs f/u |

Isolated anti-HBc: 132 (38.3%) OBI: |

No difference in change of ELF over time b/w anti-HBc and other serologies (p=0.64) | French JAIDS 2016 |

| HIV-infected, France | 240 | Isolated anti-HBc: 42 (17.5%) OBI: 13 (5.4%) |

No association between isolated anti-HBc and acute LEE | Piroth J Hepatol 2002 |

| HIV-infected, USA, ACTG, cross-sectional | 240 | Isolated anti-HBc: 38 (15.8%) OBI: 4 (10.5%) |

No association between ALT levels and HBV DNA positivity | Shire JAIDS 2004 Shire JAIDS 2007 |

| HIV-infected, Turkey, cross-sectional | 209 | Isolated anti-HBc: 40 (19.1%) OBI: 7 (7.5%) |

---------------------------------------------------------- | Karaosmanoglu HIV Clin Trials 2013 |

| HIV-infected, South Africa | 192 | Isolated anti-HBc: 29 (15.1%) OBI: 11 (37.9%) |

---------------------------------------------------------- | Lukhwareni J Med Virol 2009 |

| Multi-center prospective study HIV infected, HBsAg negative, ART naïve, Italy | 115 | Isolated anti-HBc: 42 (36.5%) OBI: 17/86 (19.8%) |

32.5% (28/86) pts experienced hepatic flare (more frequent in HBV+ than negative: 64.7% of HBV+ pts vs. 24.6% HBV-) | Filippini AIDS 2006 |

| HIV-infected HBsAg– | 97 anti-HBc + | OBI: 13 (13%) | No difference in transaminitis following ART initiation | Lo Re V J Clin Virology 2008 |

| HIV-infected anti-HBc+, Switzerland, Swiss HIV Cohort Study | 57 | Isolated anti-HBc: 57 (100%) OBI: 51 (89.5%) |

In anti-HCV negative and HBV DNA positive individuals 8/22 (36.4%) had ALT elevation for 6 or more months that was directly related to HBV infection Significantly higher ALT values in 12/29 (41.4%) of HBV DNA and anti-HCV positive individuals |

Hofer Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1998 |

When specifically evaluating occult HBV infection in HIV infection, again varying associations are reported. In one cross-sectional analysis of HIV-infected women, there was no association with elevated transaminases [14]. In the setting of antiretroviral therapy initiation, two studies have demonstrated no impact on subsequent ALT elevation with ART initiation in those with occult HBV infection [22, 26] while another demonstrated elevated aminotransferases in those with HIV and OBI during ART initiation or change [21]. With regards to HBV perinatal transmission, there was no HBV perinatal transmission in a cohort of HIV infected Thai women with occult HBV infection [10].

In non-HIV infected populations, however, the association between occult HBV infection and adverse outcomes seems clearer. Two large meta-analyses have found an association with occult HBV infection and chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma [27, 28] with varying prevalence and impact depending on geography and endemicity of HBV [29]. In one study, patients with chronic hepatitis C with concomitant occult hepatitis B infection had a higher risk of death related to liver disease as compared to patients without evidence of occult HBV infection over a median of 11 years of follow-up [30]. It is notable that another small study demonstrated no association between isolated anti-HBc and increased hepatocellular carcinoma risk [31] but this may have been limited by sample size. Other studies have demonstrated reduced responses to IFN-containing regimens in HCV infected patients [32–36] although there has thus far been no association between occult HBV infection and HCV therapy response rates in the all-oral direct acting antiviral (DAA) era.

Clinical implications and the Management of the isolated anti-HBc serologic profile in HIV infection

Susceptibility to HBV Infection

In HIV infection, the presence of the isolated anti-HBc pattern does not necessarily indicate immunity to HBV infection. Indeed, varying anamnestic responses to a single dose of HBV vaccine have been reported, ranging from as low as 7% [37] to 32% [38], with higher levels of response to multiple doses of HBV vaccine administered. A prospective study conducted by Piroth and colleagues demonstrated that in 54 HIV-infected patients with the isolated anti-HBc profile, a single dose of 20 μg HBV vaccine resulted in a 46% response rate, defined as anti-HBs >10 mIU/ml; in those who did not respond to a single dose, a 3-dose series of double-dose 40 μg HBV vaccine resulted in 89% of remaining patients developing anti-HBs titers of >10 mIU/mL at 28 weeks following vaccination [39]. Based on the results of this study, the current DHHS guidelines recommend that HIV infected patients with the isolated anti-HBc profile receive one standard dose of HBV vaccine followed by anti-HBs assessment 1-2 months post dose. If anti-HBs is <100 IU/mL then the individual should receive the full series of either single or double-dose HBV vaccine, with subsequent anti-HBs testing 1-2 months after completion of the vaccine series [40].

HBV Reactivation During DAA-therapy in HCV Infected Patients

With the advent of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for the treatment and eradication of hepatitis C, a number of cases of hepatitis B reactivation have been reported in postmarketing treatment outcomes. To date, at least 29 cases have been reported to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System [41], including all serologic profiles. Where HBsAg baseline data was available, 76% of reactivation cases (13/17) occurred in patients with positive HBsAg prior to treatment. Few cases have reported baseline HBcAb testing, and it is difficult to assess how prevalent HBV reactivation is amongst patients with isolated HBcAb to date, though emerging reports on cohorts indicate that HBsAg positivity in the absence of suppressive therapy for HBV is a strong risk factor for HBV reactivation [41–55].

Smaller cohorts such as those described in one Taiwanese and Korean cohort (n=173) have failed to show evidence of HBV reactivation[45] during HCV treatment with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir. In a larger observational cohort in China (n=327), of which 124 patients were defined as having occult HBV infection, 3 cases of HBV reactivation have been noted [44] associated with HCV DAA treatment. A large, retrospective evaluation of 62,920 veterans treated for hepatitis C identified 9 patients (0.01%) with evidence of HBV reactivation during DAA therapy, one of these nine patients tested positive for isolated HBcAb [42]. Though HBV reactivation would seem in this large retrospective cohort to be an infrequent event, a meta-analysis by Chen and colleagues [43] found more clinical severe reports of hepatitis due to HBV reactivation in patients treated with HCV DAA therapy than interferon-based treatment, as well as an earlier onset of hepatitis in the DAA-treated populations. In general, HBV reactivation occurred 4-8 weeks after initiation of DAA-based therapy whereas HBV reactivation occurred after cessation of IFN-based HCV therapy [43]. Another retrospective study examined the prevalence of HBV reactivation comparing interferon-era versus interferon-free therapies, and found a significant proportion of patients (6/85) experienced HBV viremia during or after DAA treatment, and no cases of reactivation in the interferon based group (0/72) [55]. Together, these findings underscore the importance of screening for chronic or occult hepatitis B infection prior to treatment of HCV with DAAs.

Few data of HBV reactivation exist in HIV-infected populations with respect to interferon-based or DAA-treated cohorts. To date, there has been one case report of HBV reactivation in HIV/HCV coinfection. The patient was anti-HBc and anti-HBs positive who had an acute hepatitis and HBV DNA elevation four weeks after completion of SOF/LDV therapy for HCV. She was successfully treated with entecavir with liver enzyme normalization [50].

Mechanism of HBV Reactivation in HCV Infection

HBV and HCV have a unique viral interplay when infection with both viruses exists in one host. In general, HCV exerts an inhibitory effect on HBV, as evidenced by studies finding lower HBV viral loads in coinfection when compared with HBV monoinfected individuals [56]. Presence of HBeAg and levels of HBV DNA have been shown to be significantly lower in patients with HBV/HCV coinfection [57]. Mouse models in vivo have shown that HCV core protein has the capacity to inhibit HBV virus replication [58]. In addition, HBV and HCV may exert varying dominance over the course of each infection [59]. Interferon-based therapy can lead to HBsAg clearance [60, 61] in 30% of dual infected patients. It is hypothesized that with DAA agents, as there is no inhibitory effect on HBV as with interferon, the ability of HBV to assume viral dominance and replication in the context of HCV clearance may be responsible for cases of HBV reactivation [43].

Management of isolated anti-HBc pattern prior to treatment in HIV/HCV infection

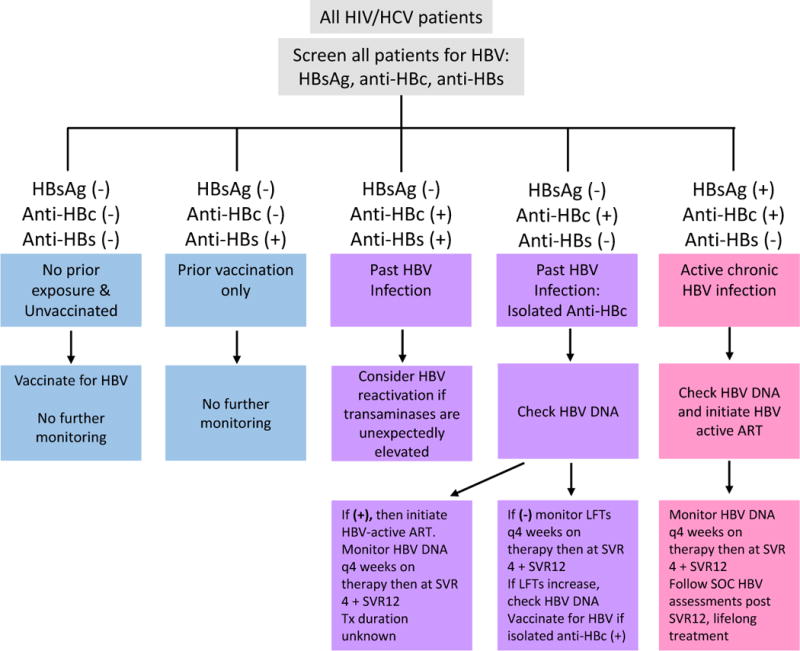

Management of isolated anti-HBc profile in HIV/HCV co-infection remains a subject of discussion, given the risk of HBV reactivation during HCV DAA treatment. In the US, both the AASLD/IDSA Treatment Guidance and the Veterans’ Affairs centers have proposed management algorithms [62, 63]. Our proposed management strategy for addressing isolated anti-HBc serologic profile based on the studies above is shown (Fig. 2). Using our algorithm, all HIV/HCV co-infected patients should be screened for HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs. If the patient is negative for all three markers, it can be concluded that they have had no prior exposure to HBV and are unvaccinated. These patients should then be vaccinated for HBV, and do not require further monitoring. HBsAg and anti-HBc negativity with concurrent positive anti-HBs only indicate that the patient has been previously vaccination with HBV, and therefore requires no further monitoring. If the individual is negative for HBsAg but is positive for both anti-HBc and anti-HBs (demonstrating past HBV infection) OR the patient is negative for HBsAg and anti-HBs and is positive for anti-HBc (signifying isolated anti-HBc), we recommend assessment of baseline HBV DNA levels. The presence of HBV DNA requires HBV-active ART initiation. If positive at baseline, HBV DNA should be monitored every 4 weeks during therapy and sustained virologic response 4 and 12 (SVR4 + SVR12) weeks after completion of therapy should also be tested. The optimal treatment duration is unknown. If lifelong therapy is not preferred, HBV active ART should be continued for at least six to twelve months after HCV end of treatment with monitoring of HBV DNA and LFTs with subsequent HBV active ART cessation. If the patient is negative for HBV DNA, their liver function tests (LFT) should be monitored every 4 weeks during therapy and at SVR12 weeks after HCV treatment cessation. An increase in LFTs would require that HBV DNA levels be checked again. Chronic HBV infection is determined by positive HBsAg and anti-HBc tests with negative anti-HBs. These patients should have their HBV DNA levels assessed and should initiate an HBV-active ART. Every 4 weeks during therapy and again at SVR4 and SVR12, the patient’s HBV DNA should be monitored. Standard of care HBV assessments should be followed post SVR12 for lifelong treatment.

Figure 2.

HBsAg: HBV surface antigen; Anti-HBc: antibody to HBV core antigen; Anti-HBs: antibody to HBsAg; HBV-active ART: Regimens containing TDF, TAF + 3TC; entecavir should not be used in patients with HIV viremia; SVR4: Undetectable HCV RNA 4 weeks after end of therapy; SVR12: Undetectable HCV RNA 4 weeks after end of therapy; LFTs: liver function tests; SOC: standard of care

Modified from: Jacinta A. Holmes, Ming-Lung Yu & Raymond T. Chung (2017) Hepatitis B reactivation during or after direct acting antiviral therapy – implication for susceptible individuals, Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 16:6, 651-672, DOI: 10.1080/14740338.2017.1325869

Summary/Conclusions

The isolated anti-HBc pattern (HBsAg(-)/anti-HBc(+)/anti-HBs (-) occurs in 17-40% of HIV-infected individuals1,6,9,10 and in most cases, represents a waning host immune response to HBV infection. The presence of anti-HBc denotes a transcriptionally active reservoir that can result in HBV reactivation. Whether the isolated anti-HBc pattern is associated with greater morbidity in HIV infected patients is unclear, but large meta-analyses have demonstrated an association with occult HBV infection (one part of the isolated anti-HBc pattern) with chronic liver disease and HCC in non-HIV infected individuals. The isolated anti-HBc pattern is particularly relevant in HIV/HCV coinfected patients, both with respects to susceptibility to HBV infection and during DAA therapy. HBV reactivation has emerged in the era of DAA treatment of HCV infection, with varying consequences in morbidity ranging from asymptomatic infection, to elevations in transaminases and/or resultant liver transplantation. Current guidelines recommended by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)52, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), and the Veterans’ Affairs recommend screening for HBsAg, HBsAb, and anti-HBc prior to consideration of treatment of HCV infection. Adherence to these recommendations and management of occult or isolated anti-HBc, as outlined here, may be essential in the prevention of HBV reactivation and subsequent morbidity that was less appreciated in the interferon-era of HCV treatment.

Table 3.

HBV Reactivation in HCV-Infected Patients Receiving DAA therapy

| Cohort | DAAs | N | Cohort | Other outcomes: ALT elevation, clinical illness, HBsAg appearance | HBV DNA elevation | Hepatic Decompensation, liver transplant, death | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective evaluation of veterans receiving DAAs from VA | SOF/SIM LDV/SOF OBV/PTV/r+DSV EBR/GRZ SOF/VEL |

N=62,290 | HBsAg+ (n=377) Isolated anti-HBc+ (n=7295) |

HBsAg+: 6/8 with HBV DNA elevation with ALT elevation Isolated anti-HBc: 0 of 390 tested had appearance of HBsAg |

HBsAg+: n=8 with HBV DNA >1000 IU/ml from BL Isolated anti-HBc: 4 of 173 tested had elevated HBV DNA, 1 with HBV DNA >1000 IU/ml from baseline |

Not reported | Belperio Hepatol 2017 |

| Meta-analysis of HCV patients receiving DAA vs IFN containing therapy* | DAAs IFN |

28 studies (chronic HCV pts with overt and occult HBV N=779) | HBsAg+ HBsAg(−) and HBV DNA+ |

ALT elevation: HBsAg+: 12.2 % DAA 0% IFN HBsAg(-) and HBV DNA+: 2 case reports DAA 0 IFN |

HBsAg+: 12.2% DAA 14.5% IFN HBsAg(-) and HBV DNA+: 3 case reports DAA 0 IFN |

Not reported | Chen Hepatol 2017 |

| Prospective observational cohort study, China | LDV/SOF DAC/SOF Viekira Pak |

N=327 | HBsAg+ (n=10) Occult HBV (n=124) |

HBsAg+: 30% with hepatitis associated with HBV reactivation Occult HBV: 0% |

Not reported | N=2 with jaundice or liver failure | Wang CGH 2017 |

| Retrospective cohort study; Taiwan/Korea | SOF/LDV | N=173 | Anti-HBc + (n=103) | 1 had grade 3 ALT elevation at wk 3 (up from grade 2 at BL) | 2 with HBV DNA detectable | Sulkowski CID 2016 | |

| Prospective cohort study (Taiwan) | IFN-free DAAs | 93 (12 HBsAg+, 81 HBsAg negative) | Anti-HBc + | 16.7% HBsAg+ 0 HBsAg- |

Liu Open Forum Infect Dis 2017 | ||

| Reported cases to FDA FAERS | Viekira Pak/RBV DCV/ASV SIM/SOF SIM/SOF/RBV SOF/RBV LDV/SOF SIM/PEG/RBV DCV/ASV DCV/SOF/RBV LDV/SOF/RBV |

N=29 | HBsAg+(n=13) Anti-HBc+(n=6) HBV DNA+ (n=9) |

8/29 (29%) with clinical illness | % not reported | Decompensated liver failure in 3 patients 2 deaths 1 liver transplant |

Bersoff-Matcha Ann Intern Med 2017 |

| Prospective observational study; New Zealand | SOF/LDV | N=8 | HBsAg+ | 0 with clinical flare | 7/8 with HBV DNA elevation | None | Gane Antivir Ther 2016 |

| Case study | SOF/SIM | 1 | NA | ALT increased from 62 IU/L before DAAs to 1495 IU/L | Increased HBV DNA from 2.3 IU/mL before DAAs to 22 million after | Hepatic decompensation (jaundice) | Collins Clin Infect Dis 2015 |

| Case study | LDV/SOF | 1 | NA | ALT elevation | From undetectable before DAAs to 8.9 log IU/mL after DAAs | Hepatic decompensation | De Monte J Clin Virol 2016 |

| Case report | LDV/SOF | 1 | OBI: HBV DNA in HBsAg- patients | ALT elevation/hepatitis after DAA termination | Increased HBV DNA | NA | Fabbri BMC Infect Dis 2017 |

| Case report | Prev IFN/RBV SIM/SOF/RBV |

1 | NA | ALT elevation after DAA initiation | Increased HBV DNA | Fulminant hepatic failure requiring liver transplant | Ende J Med Case Rep 2015 |

| Case study | DAC/ASV | 1 | NA | ALT elevation after DAA initiation | Increased HBV DNA | Acute liver failure (treated with entecavir), recovered | Hayashi Clin J Gastroenterol 2016 |

| Case study | SOF/RBV | 1 | NA | ALT elevation after DAA initiation | Increased HBV DNA | Hepatic flare then treated with tenofovir | Madonia Liver Int 2016 |

11 studies included in meta-analysis did not have a clear definition for HBV reactivation but are included under HBV DNA elevation

Footnotes

Current HIV/AIDS reports

References

- 1.Bhattacharya D, Tseng CH, Tate JP, et al. Isolated Hepatitis B Core Antibody is Associated With Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis in HIV/HCV Infection But Not in HIV Infection Alone. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(1):e14–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000941. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondot ML, Bruss V, Kann M. Intracellular transport and egress of hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol. 2016;64(1 Suppl):S49–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.008. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden S, Locarnini S, Chang TT, et al. Covalently closed-circular hepatitis B virus DNA reduction with entecavir or lamivudine. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(15):4644–51. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4644. doi: https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoulim F. New insight on hepatitis B virus persistence from the study of intrahepatic viral cccDNA. J Hepatol. 2005;42(3):302–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.12.015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witt MD, Lewis RJ, Rieg G, Seaberg EC, Rinaldo CR, Thio CL. Predictors of the isolated hepatitis B core antibody pattern in HIV-infected and -uninfected men in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(4):606–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis908. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shire NJ, Rouster SD, Rajicic N, Sherman KE. Occult hepatitis B in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(3):869–75. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JW, Lee SH, Park YS, et al. Replicative activity of hepatitis B virus is negatively associated with methylation of covalently closed circular DNA in advanced hepatitis B virus infection. Intervirology. 2011;54(6):316–25. doi: 10.1159/000321450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000321450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samal J, Kandpal M, Vivekanandan P. Molecular mechanisms underlying occult hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(1):142–63. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00018-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00018-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palacios R, Mata R, Hidalgo A, et al. Very low prevalence and no clinical significance of occult hepatitis B in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with isolated anti-HBc seropositivity: the BHOI study. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9(5):337–40. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-337. doi: https://doi.org/10.1310/hct0905-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khamduang W, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Gaudy-Graffin C, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and impact of isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen and occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-1-infected pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1704–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit166. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neau D, Winnock M, Jouvencel AC, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected patients with isolated antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen: Aquitaine cohort, 2002-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):750–3. doi: 10.1086/427882. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/427882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firnhaber C, Viana R, Reyneke A, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with isolated core antibody and HIV co-infection in an urban clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(4):488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.08.018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha D, Pal A, Sarkar N, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV positive patients at a tertiary healthcare unit in eastern India. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179035. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsui JI, French AL, Seaberg EC, et al. Prevalence and long-term effects of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(6):736–40. doi: 10.1086/520989. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/520989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chadwick D, Stanley A, Sarfo S, et al. Response to antiretroviral therapy in occult hepatitis B and HIV co-infection in West Africa. AIDS. 2013;27(1):139–41. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283589879. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283589879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French AL, Hotton A, Young M, et al. Isolated Hepatitis B Core Antibody Status Is Not Associated With Accelerated Liver Disease Progression in HIV/Hepatitis C Coinfection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(3):274–80. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000969. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piroth L, Binquet C, Vergne M, et al. The evolution of hepatitis B virus serological patterns and the clinical relevance of isolated antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen in HIV infected patients. J Hepatol. 2002;36(5):681–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shire NJ, Rouster SD, Stanford SD, et al. The prevalence and significance of occult hepatitis B virus in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(3):309–14. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802e29a9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802e29a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karaosmanoglu HK, Aydin OA, Nazlican O. Isolated anti-HBc among HIV-infected patients in Istanbul, Turkey. HIV Clin Trials. 2013;14(1):17–20. doi: 10.1310/hct1401-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1310/hct1401-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukhwareni A, Burnett RJ, Selabe SG, Mzileni MO, Mphahlele MJ. Increased detection of HBV DNA in HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative South African HIV/AIDS patients enrolling for highly active antiretroviral therapy at a Tertiary Hospital. J Med Virol. 2009;81(3):406–12. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21418. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.21418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filippini P, Coppola N, Pisapia R, et al. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV patients naive for antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20(9):1253–60. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000232232.41877.2a. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000232232.41877.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo Re V, 3rd, Wertheimer B, Localio AR, et al. Incidence of transaminitis among HIV-infected patients with occult hepatitis B. J Clin Virol. 2008;43(1):32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.030. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofer M, Joller-Jemelka HI, Grob PJ, Luthy R, Opravil M. Frequent chronic hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected patients positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen only. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17(1):6–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01584356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang SH, Chen TJ, Lee SS, et al. Risk factors of isolated antibody against core antigen of hepatitis B virus: association with HIV infection and age but not hepatitis C virus infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(2):122–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181daafd5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181daafd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.French AL, Operskalski E, Peters M, et al. Isolated hepatitis B core antibody is associated with HIV and ongoing but not resolved hepatitis C virus infection in a cohort of US women. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(10):1437–42. doi: 10.1086/515578. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/515578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pogany K, Zaaijer HL, Prins JM, Wit FW, Lange JM, Beld MG. Occult hepatitis B virus infection before and 1 year after start of HAART in HIV type 1-positive patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21(11):922–6. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.922. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2005.21.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Covolo L, Pollicino T, Raimondo G, Donato F. Occult hepatitis B virus and the risk for chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(3):238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.09.021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Y, Wu YH, Wu W, Zhang WJ, Yang J, Chen Z. Association between occult hepatitis B infection and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2012;32(2):231–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02481.x. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makvandi M. Update on occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(39):8720–34. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i39.8720. doi: https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i39.8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Squadrito G, Cacciola I, Alibrandi A, Pollicino T, Raimondo G. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection on the outcome of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(4):696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.043. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lok AS, Everhart JE, Di Bisceglie AM, et al. Occult and previous hepatitis B virus infection are not associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in United States patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):434–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.24257. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(1):22–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199907013410104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zignego AL, Fontana R, Puliti S, et al. Relevance of inapparent coinfection by hepatitis B virus in alpha interferon-treated patients with hepatitis C virus chronic hepatitis. J Med Virol. 1997;51(4):313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Hamamoto S, et al. Co-infection by serologically-silent hepatitis B virus may contribute to poor interferon response in patients with chronic hepatitis C by down-regulation of type-I interferon receptor gene expression in the liver. J Med Virol. 2001;63(3):220–7. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200103)63:3<220::aid-jmv1004>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Niigaki M, et al. Serologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance. J Med Virol. 1999;58(3):201–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199907)58:3<201::aid-jmv3>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Maria N, Colantoni A, Friedlander L, et al. The impact of previous HBV infection on the course of chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3529–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03371.x. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jongjirawisan Y, Ungulkraiwit P, Sungkanuparph S. Isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen in HIV-1 infected patients and a pilot study of vaccination to determine the anamnestic response. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(12):2028–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakvetadze C, Bani-Sadr F, Le Pendeven C, et al. Serologic response to hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-Infected patients with isolated positivity for antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(8):1184–6. doi: 10.1086/651422. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/651422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piroth L, Launay O, Michel ML, et al. Vaccination Against Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) in HIV-1-Infected Patients With Isolated Anti-HBV Core Antibody: The ANRS HB EP03 CISOVAC Prospective Study. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(11):1735–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw011. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2017 Aug; https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/4/adult-and-adolescent-oi-prevention-and-treatment-guidelines/344/hbv.

- 41.Bersoff-Matcha SJ, Cao K, Jason M, et al. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation Associated With Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus: A Review of Cases Reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(11):792–98. doi: 10.7326/M17-0377. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Mole LA, Backus LI. Evaluation of hepatitis B reactivation among 62,920 veterans treated with oral hepatitis C antivirals. Hepatology. 2017;66(1):27–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.29135. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen G, Wang C, Chen J, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in hepatitis B and C coinfected patients treated with antiviral agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(1):13–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.29109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C, Ji D, Chen J, et al. Hepatitis due to Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus in Endemic Areas Among Patients With Hepatitis C Treated With Direct-acting Antiviral Agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(1):132–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.023. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sulkowski MS, Chuang WL, Kao JH, et al. No Evidence of Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus Among Patients Treated With Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(9):1202–04. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw507. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu CH, Liu CJ, Su TH, et al. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation in Patients Receiving Interferon-Free Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):ofx028. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx028. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gane EJ, Hyland RH, An D, Svarovskaia ES, Brainard D, McHutchison JG. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for HCV infection in patients coinfected with HBV. Antivir Ther. 2016;21(7):605–09. doi: 10.3851/IMP3066. doi: https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collins JM, Raphael KL, Terry C, et al. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation During Successful Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus With Sofosbuvir and Simeprevir. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(8):1304–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ474. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Monte A, Courjon J, Anty R, et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment in adults infected with hepatitis C virus: Reactivation of hepatitis B virus coinfection as a further challenge. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.02.026. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fabbri G, Mastrorosa I, Vergori A, et al. Reactivation of occult HBV infection in an HIV/HCV Co-infected patient successfully treated with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2287-y. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2287-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ende AR, Kim NH, Yeh MM, Harper J, Landis CS. Fulminant hepatitis B reactivation leading to liver transplantation in a patient with chronic hepatitis C treated with simeprevir and sofosbuvir: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:164. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0630-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0630-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayashi K, Ishigami M, Ishizu Y, et al. A case of acute hepatitis B in a chronic hepatitis C patient after daclatasvir and asunaprevir combination therapy: hepatitis B virus reactivation or acute self-limited hepatitis? Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9(4):252–6. doi: 10.1007/s12328-016-0657-4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-016-0657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madonia S, Orlando E, Madonia G, Cannizzaro M. HCV/HBV coinfection: The dark side of DAAs treatment? Liver Int. 2017;37(7):1086–87. doi: 10.1111/liv.13342. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loggi E, Gitto S, Galli S, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation among hepatitis C patients treated with direct-acting antiviral therapies in routine clinical practice. J Clin Virol. 2017;93:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.05.021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawagishi N, Suda G, Onozawa M, et al. Comparing the risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation between direct-acting antiviral therapies and interferon-based therapies for hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24(12):1098–106. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12737. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jardi R, Rodriguez F, Buti M, et al. Role of hepatitis B, C, and D viruses in dual and triple infection: influence of viral genotypes and hepatitis B precore and basal core promoter mutations on viral replicative interference. Hepatology. 2001;34(2):404–10. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26511. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dai CY, Yu ML, Chuang WL, et al. Influence of hepatitis C virus on the profiles of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16(6):636–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu W, Wu C, Deng W, et al. Inhibition of the HCV core protein on the immune response to HBV surface antigen and on HBV gene expression and replication in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045146. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Konstantinou D, Deutsch M. The spectrum of HBV/HCV coinfection: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, viralinteractions and management. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(2):221–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu ML, Lee CM, Chen CL, et al. Sustained hepatitis C virus clearance and increased hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance in patients with dual chronic hepatitis C and B during posttreatment follow-up. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2135–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.26266. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(26):2682–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.AASLD/IDSA. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. 2017 Apr; www.hcvguidelines.org.

- 63.VA HIV, Hepatitis, and Public Health Pathogens Program. Recommendations for Hepatitis B Viral Infection Testing and Monitoring among HCV-Infected Veterans Being Considered for DAA Treatment. 2016 Oct; https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/hbv-recommendations-hcv-daa-treatment.pdf.