Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: documentation, emergency service hospital, language, subjective health complaint, translating

Abstract

Objectives

The patient’s presenting complaint guides diagnosis and treatment in the emergency department, but there is no classification system available in German. The Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List (PCL) is available only in English and French. As translation risks the altering of meaning, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) has set guidelines to ensure translational accuracy. The aim of this paper is to describe our experiences of using the ISPOR guidelines to translate the CEDIS PCL into German.

Materials and methods

The CEDIS PCL (version 3.0) was forward-translated and back-translated in accordance with the ISPOR guidelines using bilingual clinicians/translators and an occupationally mixed evaluation group that completed a self-developed questionnaire.

Results

The CEDIS PCL was forward-translated (four emergency physicians) and back-translated (three mixed translators). Back-translation uncovered eight PCL items requiring amendment. In total, 156 comments were received from 32 evaluators, six of which resulted in amendments.

Conclusion

The ISPOR guidelines facilitated adaptation of a PCL into German, but the process required time, language skills and clinical knowledge. The current methodology may be applicable to translating the CEDIS PCL into other languages, with the aim of developing a harmonized, multilingual PCL.

Introduction

Patients attending the emergency department usually do so with one or more symptoms or physical signs, often referred to as the ‘presenting complaint’ (PC) or ‘chief complaint’. This crucial information guides initial assessment and forms the basis for reaching a diagnosis, risk stratification and early treatment 1. By comparison, most analyses of the emergency care provided rely on auditing cohorts of patients with a specific diagnosis. This can lead to inaccuracies, for example, if a diagnosis is subsequently altered or excluded. An alternative approach is to examine the reason for attendance. Studying PCs facilitates a clearer examination of the diagnostic process and, consequently, how well the emergency department is performing 2. In Germany, diagnoses are encoded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, German Modification (ICD-10-GM), but there is no comparable classification system for PCs applicable to emergency medicine. Consequently, PCs are not routinely encoded; rather, they are variably recorded as additional free-text information somewhere in the admission documentation. This complicates data analysis and interferes with reliable benchmarking, auditing and research 3.

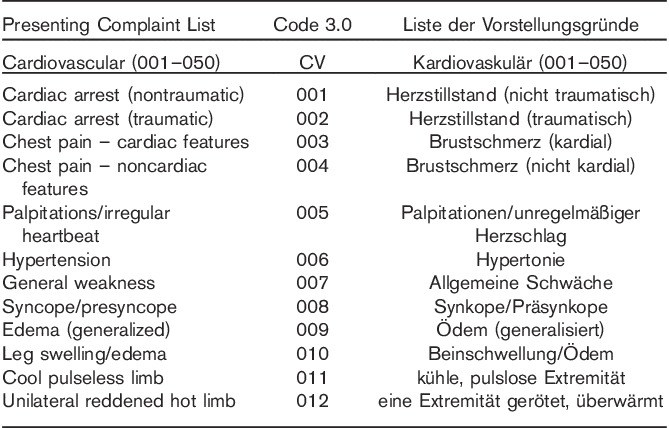

A national documentation standard for emergency departments was established in 2010 by the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 4,5. During a revision process, it became clear that details of patients’ PC needed to be recorded using a classification system 6. A literature review was performed with the aim of identifying a credible PC list used widely by the scientific community. The Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaints List (PCL) developed by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) was identified as an optimal solution 7,8. The CEDIS PCL is available in both official Canadian languages: English and French. It consists of 171 signs and symptoms grouped into 17 categories; Table 1 represents an extract from the CEDIS PCL. Introduction of the CEDIS PCL necessitated that it be translated for the German user. Nonmodification of the CEDIS PCL during the translation process was a prerequisite to preserve international comparability. A hasty, poorly considered translation may unintentionally alter some concepts and meanings, and thus limit the tool’s equivalence across languages and cultural regions. To avoid such situations, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) published the Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures 9.

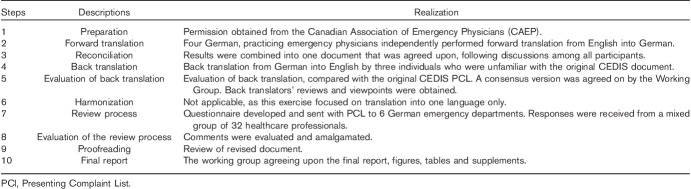

Table 1.

Sample from the original Presenting Complaint List with German translation

The aim of this paper is to describe our experiences of using the ISPOR guidelines to translate the CEDIS PCL into German.

Materials and methods

The project involved a convenient ‘Working Group’ recruited from the German Interdisciplinary Association for Emergency and Acute Medicine and German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, whose role was to initiate and manage the project. Table 2 provides an overview of the methodology used. We began by acquiring the most recent English version of the CEDIS PCL (3.0) 10. Furthermore, we acquired permission for translation from the author (step 1 of methodology). The ‘Translation Group’ comprised four ‘forward’ translators (English into German), all German native speakers and experienced emergency physicians with a working knowledge of English and German. They independently translated the PCL into German (step 2). The German terms were compared with each other. Where there was limited agreement, the results were carefully considered, resulting in a single forward translation (step 3). The three ‘back’ translators who independently translated the PCL back to German were medically qualified, bilingual English native speakers working in the UK and Germany, and one was a professional translator affiliated with the German Federal Office of Languages. None of the back translators were familiar with the original CEDIS PCL (step 4). The back translations were reviewed by the Working Group; the terms suggested were compared with the original wording in the CEDIS PCL. Lack of agreement indicated a problem with the forward-translation process and led to further review of the German translation (step 5). Small variations between participants were accepted as showing agreement, for example, where the translator used a singular or a plural form, different spellings and word order. We expanded on the review of the back translations advocated by the ISPOR in step 5 by asking the back translators to review the revised German version. Step 6 could be omitted as there were no different language versions to harmonize.

Table 2.

The various translation stages used in this project according to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research methodology 10

The resultant German version was reviewed by a diverse ‘Evaluation Group’ of emergency personnel working in six German hospitals. We developed our own questionnaire (SDC 1, supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A154), aimed at eliciting respondents’ opinions on the overall German version of the CEDIS PCL, specifically, views on its anticipated applicability in routine clinical practice and individual items of the PCL (step 7). The returned completed questionnaires were reviewed, resulting in final changes to the German version of PCL by the Working Group (step 8). Proofreading (step 9) and development of this paper, which constitutes the final report (step 10), followed. A table detailing all intermediate steps, results and modifications made to the German version during the translation process is available at SDC 2 (Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A155).

The data were analysed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA). Because no patients were involved in this study, approval by the Ethics Committee was considered unnecessary.

Results

Translation process

There was limited agreement among the four forward translators tasked with translating the CEDIS PCL into German. In 98 (57%) of 171 PCs, there was either complete lack of agreement or agreement between only two translators, with the other two proposing different wording. In the remaining 73 (43%) PCs, either three or all four translations were identical. The former PCs generated considerable discussion at step 3, whereas reconciliation was generally easier for the latter group.

The results of the back-translation process were better compared with those of initial translation from the English original. In 94 (55%) of 171 PCs, the wording of two or all three back translations was identical to that in the CEDIS PCL. This meant that approval of the chosen German translation at step 5 was generally easier. However, in 77 (45%) PCs, there was limited or no agreement. This necessitated a detailed exploration in terms of generating optimal wording.

The most common cause of differences between the back translation and the original version was the use of synonyms. For example, for PCL code 406, ‘Gait disturbance/ataxia’ was forward-translated into German as ‘Gangstörung/Ataxie’. Back translation yielded the following wording: ‘Gait disorder/ataxia’, ‘Gait problems/ataxia’ and ‘gait disorder/ataxia’. Although the back translations all differed from the original, they were considered synonyms and, consequently, no change to the forward translation was necessary.

For eight of the items, back translation yielded an unintentional change in meaning, compared with the original, thus necessitating modification. For example, the PCL code 008 ‘Syncope/presyncope’ was translated as ‘Synkope/Kollaps’ and consistently back-translated by all three translators as ‘Syncope/Collapse’. Most emergency physicians would consider ‘presyncope’ a different concept from ‘collapse’; thus, the translation was modified to ‘Synkope/Präsynkope’ (SDC 2, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A155).

Further, in 12 PCs, intentional modification of the original was necessary because there was no equivalent wording or usage in the German language. For example, PCL code 003, ‘Chest pain – cardiac features’, was intentionally translated as ‘Brustschmerz (kardial)’ because there is no equivalent German translation for the word, ‘feature’, in this context. Similarly, because of the lack of appropriate German equivalents to enable a distinction between ‘Sore throat’ and ‘Neck swelling/pain’ (PCL codes 103 and 104), with both words being translated as ‘Halsschmerzen’, an expanded form of wording had to be adopted for clarity.

Feedback from the back translators (Table 2; step 5) led to the identification of several unintentional modifications and necessitated 14 language improvements. This occurred when the German translation was linguistically too close to the English original. Here is an example: PCL code 503, ‘Foreign body, eye’, was originally translated as ‘Fremdkörper Auge’, whereas the more correct linguistic expression in German should be ‘Fremdkörper im Auge’.

The German translation of the CEDIS PCL is available at SDC 3, Supplemental digital content 3, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A156.

Evaluation process (steps 7 and 8)

A total of 32 completed questionnaires were received from the Evaluation Group members. Respondents comprised six physicians, 16 nurses, one paramedic and seven medical assistants, with two participants not reporting their occupations. Female participants were in the majority (n=19). Respondents’ average age was 35 years and they had, on average, 7 years’ work experience in emergency medicine. Twenty-nine members of the Evaluation Group commented on the general applicability of the PCL to the German emergency practice; 18 (62%) were positive, seven (24%) were neutral and four (14%) were negative.

Of the 156 comments received, 40 were general observations relating to the structure of the CEDIS PCL; these were not related to the translation process. Those giving positive responses agreed that all presenting complaints were adequately covered by the PCL. Negative comments mostly entailed requests to add more subsections to the list to address perceived incomplete information or the level of item detail. Forty-two more comments referred to PCs that were considered to have been completely omitted from the list. The remaining 74 comments pertained to individual terms of the list, six of which resulted in changes to the German version. One example is ‘Anorexia’ (PCL code 252), which had been translated as ‘Anorexie’, a term that is more commonly associated with anorexia nervosa in the German language. This term was subsequently changed to ‘Appetitlosigkeit’ (‘Appetite loss’).

Discussion

In this paper, we describe our experiences of using the ISPOR guidelines to translate and adapt the CEDIS PCL from English into German for local healthcare personnel on the basis of comments from an occupationally mixed group of evaluators. The aim of this study was to develop a German version of the CEDIS PCL, which is compatible with and equivalent to the English original. This process took time, language skills and medical knowledge; these considerations are relevant to other translation exercises in medical practice. A hasty, forward-translation only by one individual would have likely resulted in significant errors, reducing equivalence with the original document. Having applied the ISPOR guidelines, we feel confident that the resultant German translation of the CEDIS PCL is as good as we could get at present and is sufficient for introduction into emergency practice on a limited scale before further review.

Translating from one language to another poses the risk of altering the intended concepts and/or meanings of words or phrases. This can be particularly important in medical practice. Another issue to be considered is ensuring appropriate cultural adaptation. This may necessitate more creative use of wording in the new language, rather than direct translation. The Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation guidelines were originally developed by an ISPOR taskforce to address such issues, in respect of patient outcome measures 9, and have since been used elsewhere in numerous studies 11–13.

Our translation experience is also positive; use of the ISPOR guidelines helped us avoid a number of errors. Each step of the process showed a number of unintended changes in meaning, which required refinement of the German translation.

The latest version of the CEDIS PCL list is protected by a Creative Common License. This allows usage and dissemination of the original list, but not transmission of an altered document, such as a translated version. Consequently, we sought the permission of the licence holder to translate the CEDIS PCL and subsequently involved him in the translation process and clarification of any areas of difficulty.

A strength of this study is the involvement of four translators with emergency medicine experience, whose mother tongue is German, and who possess working knowledge of English. This is compatible with the ISPOR recommendation (step 2: ‘forward translation’) of using two or more translators. On the basis of our experience, we would not recommend such few translators for even a simple medical translation exercise.

Again, we were more diligent with our back translation. We employed three translators (the guidelines stipulate at least one) and requested them to review the revised forward translation from the English original. Their comments sharpened our translation, enabling us to identify differences and improve language quality. This reduced the risk of mistranslation in the various rounds of forward translation and mirrors previous findings by Breuer et al. 11.

Our Evaluation Group members were all experienced emergency personnel from various backgrounds, who were working in Accident and Emergency departments across Germany. They were generally positive about the usefulness and applicability of the German version. Negative comments were typically related to the level of detail within the PCL, some of which we could not resolve without changing the document to something that was no longer equivalent to the CEDIS original, as developed by the CAEP. We chose not to do this as significant changes would have generated a new, nonequivalent list that, like so many before it, would be prone to limited dissemination across other Accident and Emergency departments 14,15.

Limitations of the study

At the beginning of the translation process, we omitted to provide a clear explanation of the concepts on which the CEDIS PCL was based. This led to confusion. Moreover, we did not state whether our aim was to seek a literal translation or one that was conceptually correct. A decision to emphasize the former was only made after the study had begun.

None of the translators had previous experience of using ISPOR guidelines, and therefore required a steep learning curve. A further limitation was that the ‘Working’ and ‘Translation’ groups consisted primarily of physicians, whereas the majority of future users are likely to be nurses and associated healthcare staff (e.g. paramedics or doctors’ receptionists).

Conclusion

The translation method advocated by the ISPOR has been put into practice and found to be useful for the translation of the CEDIS PCL from English into German. This was an intensive process, with reviews and modification at each stage. Subsequent examination by an occupationally mixed Evaluation Group led to further modification. Our experience is that use of a less intensive methodology other than the ISPOR guidelines would have likely introduced several potentially significant errors.

The challenges of translating medical tools from foreign languages into a native language are not confined to the German language. The methodology applied in this study could be used to translate the CEDIS PCL into different languages that are used in Europe.

We intend implementing the translated PCL in Germany for use in complaint-based quality benchmarking, research and allowing comparisons across existing CEDIS PCL users. Translation of the CEDIS PCL into other languages using the ISPOR methodology could harmonize global research in emergency medicine.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website (www.euro-emergencymed.com).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to our colleagues at the CAEP for giving us permission to use the CEDIS PCL and for their support in the development of a German version. We acknowledge the help of our reviewers and their many valuable comments. We thank the German Federal Office of Languages for translational services. The authors would also like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing of the revised manuscript.

Dominik Brammen and Felix Greiner received grants from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research: 01KX1319A.

Martin Kulla declares grants received from the German Federal Ministry of Defence [Grant: SoFo 34K3-17 1515 (Medical Mission Registry of the German Armed Forces)] during the conduct of the study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fleischmann T, Alscher MD. Klinische Notfallmedizin: Zentrale und interdisziplinäre Notaufnahmen. Mänchen: Elsevier Urban & Fischer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffey RT, Pines JM, Farley HL, Phelan MP, Beach C, Schuur JD, et al. Chief complaint-based performance measures: a new focus for acute care quality measurement. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 65:387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Travers DA, Haas SW. Evaluation of emergency medical text processor, a system for cleaning chief complaint text data. Acad Emerg Med 2004; 11:1170–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulla M, Baacke M, Schöpke T, Walcher F, Ballaschk A, Röhrig R, et al. Core dataset ‘Emergency Department’ of the German Interdisciplinary Association of Critical Care an Emergency Medicin (DIVI). Notfall Rettungsmed 2014; 17:671–681. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulla M, Rohrig R, Helm M, Bernhard M, Gries A, Lefering R, et al. National data set ‘emergency department’: development, structure and approval by the Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung fär Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin. Anaesthesist 2014; 63:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mockel M, Searle J, Muller R, Slagman A, Storchmann H, Oestereich P, et al. Chief complaints in medical emergencies: do they relate to underlying disease and outcome? The Charité Emergency Medicine Study (CHARITEM). Eur J Emerg Med 2013; 20:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grafstein E, Unger B, Bullard M, Innes G. Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List (Version 1.0). CJEM 2003; 5:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grafstein E, Bullard MJ, Warren D, Unger B. Revision of the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List version 1.1. CJEM 2008; 10:151–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005; 8:94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List (V3.0). Available at: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?pf=PFC2737&lang=en&media=0; 2015. [Accessed 28 January 2015].

- 11.Breuer J-P, Seeling M, Barz M, Baldini T, Scholtz K, Spies C. A standardised German translation of the STAndards for Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy studies (STARD statement): methodological aspects [Article in German]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2012; 106:500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lätz A, Radtke FM, Franck M, Seeling M, Gaudreau J-D, Kleinwächter R, et al. The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NU-DESC) [Article in German]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 2008; 43:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossmann FF, Nickel CH, Christ M, Schneider K, Spirig R, Bingisser R. Transporting clinical tools to new settings: cultural adaptation and validation of the Emergency Severity Index in German. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57:257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malmström T, Huuskonen O, Torkki P, Malmström R. Structured classification for ED presenting complaints – from free text field-based approach to ICPC-2 ED application. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012; 20:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter-Storch R, Olsen UF, Mogensen C. Admissions to emergency department may be classified into specific complaint categories. Dan Med J 2014; 61:A4802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website (www.euro-emergencymed.com).