Abstract

We aimed to assess the accuracy of self-assessment for acute stroke patients via mobile phone application-based scales and determine the value and prospect of clinical use.

A cross-sectional study was designed and acute stroke patients were enrolled. We pushed the modified Rankin scale (mRS) and activities of daily living (ADL) scale to patients via mobile phone application for self-assessment on the day before they were out of hospital. We compared the results from nurse assessment and self-assessment.

Around 50 patients with the average age 51.72 ± 12.40 completed the self-assessment. A total of 27 patients self-assessed the scales, while caregivers of other 23 patients completed the assessment. In comparison with patient assessment and nurse assessment, significant difference was found in ADL score (P = .004), but was not found in mRS score (P > .05). When comparing caregiver assessment with nurse assessment, no significant difference could be found either in ADL score (P > .05) or in mRS score (P > .05). The kappa value for self-assessment and nurse agreement of ADL was 0.720 (P = .000), with sensitivity 96.8% and specificity 82.0%. The kappa value for self-assessment and nurse agreement of mRS was 0.718 (P = .000), with sensitivity 97.6% and specificity 92.4%.

In summary, mobile phone application-based scales are generally accurate, economical and convenient for self-assessment of acute stroke patients with acceptable reliability in our small scale study. Caregivers can serve as the proper assessor when patients are out of hospital. Therefore, it is promising but still need to be further confirmed how practical to use this application in extended care and follow-up.

Keywords: acute stroke, extended care, mobile phone application, self-assessment

1. Introduction

With population aging, the incidence of stroke is rapidly increased with high morbidity, mortality and disability.[1,2] Epidemiological investigation suggests there are 7 to 8 million stroke patients in Chinese mainland with the morbidity of 220 to 250 per 100 thousand.[3] In which, 70% to 80% of patients suffer the sequelae in different extent.[4] Thus, activities of daily living are severely affected together with lower life quality and heavier burden of family and society.[5–7]

Due to Chinese limited health resource, most stroke patients stay in hospital for therapy just during the acute phase. Then they spend the rehabilitation phase at home or in health service institution of community. In order to improve the extended care and provide the information for follow-up, it is of great importance to regularly obtain the accurate results of assessment. In general, there are mainly 2 ways of assessing, that is, face to face in hospital and follow-up via mobile equipment.

With the development of modern information technology, mobile health application provides the possibility for improving the pattern of extended care and follow-up, and makes it more timesaving, convenient and economic. For instance, mobile phone application can be used in self-assessment of patients with better operability, practicability and compliance. On the other hand, the information is easily acquired and analyzed by the hospital with professional guidance.

In this study, we aimed to assess the accuracy of self-assessment for acute stroke patients via mobile phone application-based scales and determine the value and prospect of clinical use.

2. Patients and methods

A cross-sectional study was designed. The study flow was illustrated as Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The study flow.

2.1. Patients

We enrolled the stroke patients during September and October 2016 from stroke unit, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing. Inclusion criteria were: aged 16 or more; clearly diagnosed as acute stroke (onset within 12 hours before admission); owned a smartphone; alive. Informed consent from patient and caregiver must be acquired before included.

2.2. Application

The application was designed by HRCD Science and Technology Ltd., focusing on self-assessment of acute stroke patients with friendly interface. It could be installed on smartphone Mac operation system (OS) or Android OS. During the hospitalization, professional nurse helped to introduce and install the application on smartphone of patient or caregiver with agreement.

2.3. Assessment

One day before moving out of the hospital, the scales were pushed via software platform. Professional nurse would guide and training the patient and caregiver how to use the application. The face-to-face assessment of professional nurse was regarded as the golden standard. These professional nurses were senior nurse serving in neurology, who were independent and blinding in developing study protocol and patient's demographics. The self-assessment of patient or caregiver would be compared with golden standard. Meanwhile, the nurse and patient were paired in the future extended care and follow-up.

2.4. Scales

The assessment tools were the modified Rankin scale (mRS) and activities of daily living (ADL) scale (Fig. 2). The mRS is widely used scale for measuring the degree of disability or dependence in the daily activities of people who suffered stroke or other causes of neurological disability,[8,9] in which the score ranges from 0 to 6, suggesting from perfect health without symptoms to death: 0—no symptoms; 1—no significant disability despite symptoms; able to carry out all usual duties and activities; 2—slight disability. Able to look after own affairs without assistance, but unable to carry out all previous activities; 3— moderate disability. Requires some help, but able to walk unassisted; 4—moderately severe disability. Unable to walk without assistance and unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance; 5—severe disability. Requires constant nursing care and attention, bedridden, incontinent; 6—dead.[10] ADL scale is a world-recognized scale with most frequently used in assessing activities of daily living of stroke patient. It is simple with good reliability,[11] validity and sensitivity in predicting therapeutic effect, length of stay and prognosis. The classification of result as Barthel index was below: functional independence (61–100); moderate dependence (41–60); and severe dependence (0–40).[12]

Figure 2.

The assessment tools were mRS and ADL scale in Chinese and pushed via software platform. ADL = activities of daily living, mRS = modified Rankin scale.

2.5. Statistical analysis

We used Epidata 3.1 to set up the database with double-personnel data entry, and SPSS18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) to analyze the data. Self-assessors consisted of patients and caregivers, which were analyzed and compared to nurses, respectively. Chi-square tests were performed and the difference was considered statistically significant when P was <.05. The agreement of self-assessment and nurse assessment were measured by kappa coefficient.

2.6. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Capital Medical University. All the subjects were informed with the study procedures before entering the study.

3. Results

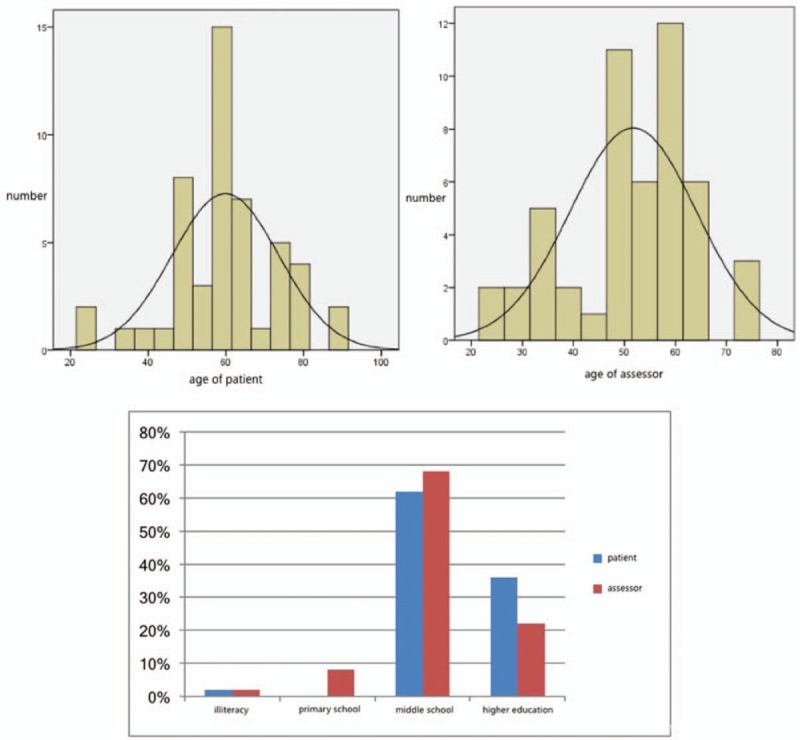

Around 56 acute stroke patients were enrolled from stroke unit, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, during September and October 2016, in which 50 patients (33 males and 17 females) completed the study with the age 24 to 88 (59.84 ± 13.73, mean ± standard deviation [SD]). While 6 patients were drop out with clear private reasons. In the 50 patients, 49 were ischemic stroke and one was hemorrhagic stroke. The score of National Institute of Health stroke scale was ranged from 0 to 22, with 4.60 ± 5.99 (mean ± SD). 27 patients self-assessed the scales, while caregivers of other 23 patients completed the assessment. Age distribution and education level of patient and assessor were illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Age distribution and education level of patient and assessor.

In comparison with patient assessment and nurse assessment, significant difference was found in ADL score (P = .004, Table 1), but was not found in mRS score (P > .05, Table 1). When comparing caregiver assessment with nurse assessment, no significant difference could be found either in ADL score (P > .05, Table 1) or in mRS score (P > .05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Result of self-assessment (patient or caregiver) and nurse assessment scale.

The consistency of ADL score between self-assessment and nurse assessment was substantial with kappa value 0.720 (P = .000, Table 2). The sensitivity and specificity were 96.8% and 82.0%, respectively. While the kappa value of mRS score was 0.718 (P = .000, Table 2), which meant a substantial consistency between self-assessment and nurse assessment. The sensitivity and specificity were 97.6% and 92.4%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Consistency test of self-assessment (patient or caregiver) and nurse assessment.

4. Discussion

In the recent years, modern information technology has rapidly developed and played an important role in solving the complexity of health care problems, especially the use of smartphones and applications provides new methods for the management of chronic diseases. Advantages of mobile phone application mainly include wide use, accurate positioning, instant information delivery and simple operation.[13,14] Due to the limitation of Chinese economic level and cultural background, there are low acceptances of mobile phone application-based investigation by patients with chronic diseases. In the past survey toward 218 chronic patients,[15] only about half of them (53.7%) would like to make use of smartphone application to improve physical activities. In which, the individuals below are prone to accepting smartphone application, including those who are below 44 years old, well-educated, ever getting benefit from exercise, willing to get health guidance via media. Our scholars have focused on the use of application in the management of stroke. However, the reliability is still unknown.

This research determines the accuracy of mobile phone application-based scales, which is pushed through software platform focusing on self-assessment of acute stroke patients. The application is time and money-saving for data acquisition and feedback to physician, and convenient for assessor to operate. It can be potentially applied in the populations with different education levels and other backgrounds. Actually, the age of application users (patients or their caregivers) ranged from 24 to 76 years old (with the average 51.72 ± 12.40). While education levels ranged from illiteracy to university degree, in which university degree were 36% and middle-school education were 62%. Caregiver assessment is much closer to nurse assessment in both of ADL and mRS scores without significant difference. Therefore, caregivers can serve as the proper assessor when patients are out of hospital. The limitation should be considered. This study is a pilot study with small sample size, which must be expanded in the future design.

In summary, mobile phone application-based scales are widely accepted by patients and their caregivers with different ages and education levels, which are generally accurate, economical and convenient for self-assessment of acute stroke patients with acceptable reliability in our small scale study. It is promising but still need to be further confirmed how practical to use this application in extended care and follow-up.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yuchen Qiao.

Data curation: Hong Chang.

Formal analysis: Jie Zhao.

Funding acquisition: Hong Chang.

Investigation: Xiaojuan Wang.

Methodology: Hui Yao.

Project administration: Hong Chang.

Resources: Juanmin Li.

Software: Yuchen Qiao, Juanmin Li.

Validation: Xiaojuan Wang, Juanmin Li.

Writing – original draft: Hong Chang, Jia Liu.

Writing – review & editing: Jia Liu.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:  ± s = mean ± standard deviation, ADL = activities of daily living, M = median, mRS = modified Rankin scale, OS = operation system, P25 = 25th percentile, P75 = 25th percentile.

± s = mean ± standard deviation, ADL = activities of daily living, M = median, mRS = modified Rankin scale, OS = operation system, P25 = 25th percentile, P75 = 25th percentile.

HC and JZ both contributed equally to this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation 2001;104:2746–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2014;383:245–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhao D, Liu J, Wang W, et al. Epidemiological transition of stroke in China: twenty-one-year observational study from the Sino-MONICA-Beijing Project. Stroke 2008;39:1668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Roming OM, Staven K. Determinants of change in quality of life from 1 to 6 months following acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;25:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lynch EA, Cadilhac DA, Luker JA, et al. Education-only versus a multifaceted intervention for improving assessment of rehabilitation needs after stroke; a cluster randomised trial. Implement Sci 2016;11:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Edwards DF, Hahn MG, Baum CM, et al. Screening patients with stroke for rehabilitation needs: validation of the post-stroke rehabilitation guidelines. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2006;20:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hakkennes S, Hill KD, Brock K, et al. Selection for inpatient rehabilitation after severe stroke: what factors influence rehabilitation assessor decision-making? J Rehabil Med 2013;45:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Newcommon NJ, Green TL, Haley E, et al. Improving the assessment of outcomes in stroke: use of a structured interview to assign grades on the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke 2003;34:377–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Saver JL, Filip B, Hamilton S, et al. Improving the reliability of stroke disability grading in clinical trials and clinical practice: the Rankin Focused Assessment (RFA). Stroke 2010;41:992–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke 2007;38:1091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, et al. The Barthel ADL index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:61–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:64–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jeon E, Park HA. Development of a smartphone application for clinical-guideline-based obesity management. Healthc Inform Res 2015;21:10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Montag C, Błaszkiewicz K, Sariyska R, et al. Smartphone usage in the 21st century: who is active on WhatsApp? BMC Res Notes 2015;8:331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sun L, Jiao C, Wang Y, et al. A survey on the willingness to use physical activity smartphone applications (apps) in patients with chronic diseases. Stud Health Technol Inform 2016;225:1032–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]