Abstract

Background

The patient’s consent to a medical procedure must be preceded by a pre-procedure discussion with the physician that is documented on a standardized form. Evidence suggests that these forms lack information that would be relevant for an informed decision.

Methods

We carried out a systematic literature search up to February 2017 for evidence on the quality and efficacy of informed consent forms. The definition of criteria for the evaluation of meta-information, content, and presentation were derived from current guidelines for evidence-based health information. As an example, we analyzed consent forms currently in use in Germany for 10 medical interventions with regard to decisionally relevant content and intelligibility of format.

Results

Our literature search yielded 14 content analyses, which revealed that even some of the more important evaluative criteria were not always met, including information on benefits (9/14), risks (14/14), alternatives (11/14), the option of doing nothing (6/14), and numerical frequencies (2/14). All analyses indicated deficiencies in the content of the consent forms. We then analyzed 37 consent forms obtained from publishing companies (across Germany) and physician’s practices in Hamburg. These forms were found to contain information on: the intervention (37/37), benefits (30/37), risks (37/37), alternatives (26/37), the option of doing nothing (4/37), numerical frequencies (10/37), the names of the authors (17/37), sources of information (0/37), and date of issue (21/37).

Conclusion

Both the evidence from foreign countries and our own analysis of the consent forms now in use in Germany revealed deficiencies, particularly in the communication of risks. New standards are needed to promote well-informed decision-making. Structural changes in the process of patient information and decision-making should be discussed.

Any invasive medical measure in fact legally constitutes an assault, if no information was provided in advance and consent obtained (1). But even if consent was obtained, affected patients may have a legitimate claim to compensation. Courts have granted rights to affected patients if they were able to provide credible proof that they had given consent only because they had not understood the existing risks in the pre-procedure discussion (2, 3). For doctors, pre-procedure discussion and consent are therefore of particular relevance in terms of civil liability law. The (Model)Professional Code for Physicians in Germany provides that consent to a medical procedure always has to be preceded by a personal pre-procedure discussion, in which the nature, importance, and scope of the treatment are explained in a comprehensible and appropriate manner, including treatment alternatives and associated risks (1). Consent is usually given in written form, and what was discussed in the pre-procedure discussion is usually recorded and documented on standardized informed consent forms.

In Germany, informed consent forms are usually purchased from publishers, as paper sheets or in digital form, sometimes featuring additional interactive tools or film clips. Informed consent forms can, however, also be produced within an institution or sourced from medical associations. The authors did not find any systematic documentation of the quality or evaluation of the informed consent forms that are currently in use in Germany. International studies have shown that consent forms are classed as hard to read (4), that risks were not completely documented (5), and that some of the information provided remained incompletely understood (6, 7).

Informed consent forms are intended to help patients understand their treatment options and be able to assess the associated risks realistically. A patient can give informed consent only if evidence-based information on benefits and harms is made available in a comprehensible form for all circumstances that may surround giving consent (8). Patients have an ethical and legal right to such an informed decision in favor of or against consenting to a medical procedure (8, 9). Quality criteria have been developed for evidence-based health information, which relate to a methodological approach to the process of developing such forms as well as to their content and the way in which information is presented (10, 11).

Objectives

According to the requirements to good scientific practice, we aimed to evaluate the internationally available evidence for the quality and effectiveness of informed consent forms. In a first step we set out a systematic overview of the evidence for the quality of the content of informed consent forms. In order to be able to reach any kind of conclusion regarding the quality of the consent forms, we critically assessed the included content analyses, especially with regard to the quality criteria applied.

In a further step we analyzed consent forms used in Germany with regard to information that is relevant to making decisions and with regard to whether the information is presented in a comprehensible format.

The study protocol was agreed in January 2016 and published on the website of the Unit of Health Sciences and Education at Hamburg University on 15 February 2016 (12).

Evidence for the quality of the content of informed consent forms

Methods

We undertook a systematic review of the evidence for the quality of the content of informed consent forms and reported this in accordance with the PRISMA statement (13); eBox 1 provides a complete explanation of the methods. The systematic literature search covered the time period up to February 2017. We included content analyses relating to the completeness and presentation of (meta-) information in informed consent forms for medical interventions. To critically appraise the quality of the included studies, we applied the methodological approach (sampling, evaluation criteria, analysis) in accordance with the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skill Programme) checklist for qualitative studies (14). The evaluation criteria used in the content analyses were extracted and matched with predefined criteria that are relevant in terms of supporting an informed decision (10, 11). Finally we extracted the results of the content analyses. The data synthesis was done descriptively: we prepared study fact sheets (SFS) for the purpose of data extraction.

Results

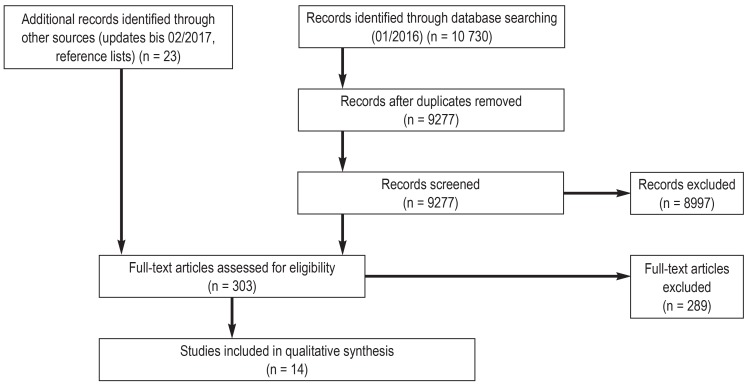

We examined 9277 database hits on the basis of titles and abstracts. We screened 303 full-text publications. 14 content analyses were included (figure). The studies had been conducted in the US (15– 21), Canada (22, 23), Europe (24– 27), and Nigeria (28); they were published between 1993 and 2016. The reported content analyses included between 10 and 540 consent forms for endoscopy (25), cataract surgery (24), prostate resection (25), angiography (16), contrast medium administration (20), transfusion medicine (18, 21), in vitro fertilization (22, 23), genetic testing (17), dental procedu-res (19), and different invasive procedures (15, 27, 28).

Figure.

Flow diagram according to the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews (13)

Quality of included studies

Sample selection

One study investigated informed consent forms from a university hospital (19), all others investigated consent forms from several different institutions. All studies described criteria for the selection of the sample of consent forms from the respective providers and users (15– 28).

Evaluation criteria

10 studies described how they drew up evaluation criteria for analyzing the content of the consent forms (15– 17, 19, 21– 24, 27, 28). The criteria were predefined on the basis of standards and recommendations for informed consent (15, 19, 21, 24, 28), assessment instruments were adapted (19, 27) or criteria taken from publications (17, 22, 23). In one study, the criteria were described on the basis of the content of the included consent forms, and the forms were evaluated once again on the basis of these items (16).

Analysis

Nine of the studies reported in detail how the analysis had been approached (15– 17, 19, 21– 23, 25, 28). The authors of six studies reported that the analyses had been undertaken by two persons independently (15, 17, 19, 21, 22, 28); interrater reliability was determined in two studies.

Evaluation criteria applied in the content analyses

The evaluation criteria differed according to the objective and extent of the analyses. Table 1 shows the extent to which the criteria that were relevant for supporting informed consent were applied. However, the criteria within categories are not consistent. For example, all 14 content analyses used criteria from the category “harm caused by the intervention” (15– 28). This can mean that risks were communicated at all (15, 16, 18– 20, 24, 26– 28), but also, that concrete predefined complications were mentioned (17, 21, 22, 25).

Table 1. Overview of evaluation criteria used in.

| Bottrell 2000 (15) | Briguglio 1995 (16) | Brown 2004 (24) | Cattapan 2016 (23) | Durfy 1998 (17) | Eisenstaedt 1993 (18) | Ezeome 2011 (28) | Gargoum 2014 (26) | Glick 2010 (19) | Hopper 1993 (20) | Krahn 2016 (22) | Montgomery 1995 (25) | Shaz 2009 (21) | Vucemilo 2015 (27) | |

| Meta-information | ||||||||||||||

| Creators/authors of the consent form | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Date of issue | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Information sources listed | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Objectives of the consent form | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – |

| Signatures (Who signs/confirms? What is being confirmed?) and legal information (e.g., cancellation rights) | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

| Further information sources mentioned | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – |

| Formal data (e.g., names and addresses) | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + |

| Content | ||||||||||||||

| Information about the intervention (e.g., type, extent, preparation, and follow-up) | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Alternatives/treatment options | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | + |

| Option of doing nothing/watchful waiting | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + |

| Diagnostics only: Information on test effectiveness (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, predictive values) | \ | \ | \ | \ | + | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| Benefit of the intervention | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + |

| Harm of the intervention | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Information on anesthesia | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Costs | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Presentation | ||||||||||||||

| Numerical presentation of frequencies/rates | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Comprehensible language (e.g., when explaining technical terms)* | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Images/figures/illustrations | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – |

| Ensuring that patients understand the information | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

+, Criterion was used; –, criterion was not used; \, criterion does not apply

defined assessment/evaluation/rating criteria, relevant for supporting informed decision-making

additional evaluation criteria that were used in the included studies

* Evaluations on the basis of readability indices were not considered.

None of the analyses considered all of the following criteria: benefit, harm, alternatives, and reported numerical frequencies. None of the studies included transparency criteria (authors, information sources, and topicality). The following are examples of criteria used above and beyond the defined criteria: reference to additional information sources (15, 16, 19, 21– 23), costs (17, 23, 24), information on anesthesia (16, 25, 28), and checking the patient’s understanding of the content of the form (15, 19). Table 1 gives an overview of the criteria used; the complete list of criteria can be found in the study fact sheets (www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/projekte/aufklaerungsboegen.html).

Results of the content analyses

The authors found (in some cases serious) substantive shortcomings in the consent forms. Because of the heterogeneity of the criteria used, we can explain results only on the basis of examples. The study fact sheets contain the complete results.

Nine of the analyses captured whether any risks had been mentioned at all (15, 16, 18– 20, 24, 26– 28). In the study reported by Brigulio et al (16), risks were at least listed in all consent forms (n=27). In the other studies, the proportion of consent forms that did not include any information on potential risks was 4–58%. Nine of the studies investigated the criterion “benefit of the intervention” (15, 17, 19, 21– 24, 27, 28); between 0 and 80.8% of forms met this criterion. Two studies investigated whether numerical frequencies had been reported (16, 26); 56% (16) and about 79% (26) of the consent forms under study (n=27 and n=61) met this criterion. 11 analyses looked at whether alternatives had been named (15– 20, 24– 28); alternative treatment options were named in 5.7–78.1% of consent forms. The proportion of forms that included doing nothing as an option was below 30% (15, 17, 19, 24, 27, 28), whereas two studies found that none of the consent forms met this criterion 24, 28).

Example-based content analysis of consent forms used in Germany

Methods

Sample and recruitment

We subjectively selected 10 interventions from different medical specialties: colonoscopy, mastectomy, percutaneous endoscopic gastroscopy (PEG), cholecystectomy, total endoprosthesis of the knee (TEP), disc prosthesis, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), stent prosthesis in aortic aneurysm, tonsillectomy, and cesarean section. We selected topics that our own working group had been involved with, which were topically and critically discussed and/or for which up to date evidence was available.

We conducted a nationwide Internet search for companies, publishers, and medical associations in Germany that develop and distribute consent forms. We invited them to participate in our project. Possible participants received written information that also assured that participation was voluntary and anonymity guaranteed. Furthermore we asked hospitals and practices in Hamburg regarding relevant consent forms.

Evaluation criteria and analysis

We drew relevant evaluation criteria for consent forms from the criteria for evidence-based health information (10, 11). From these criteria, we developed an evaluation sheet containing 15 items (etable). We included criteria on meta-information (items 1–5), contents (items 6–12), and on how the information was presented (items 13–15). Occasionally an item would consist of several criteria that may be dependent on one another (for example: information sources are named. A positive rating is followed by the question of whether it is possible to assign this to a particular information source.) Each criterion can be rated as “met yes/no,” individual ones also as “partly met.” A criterion (for example: benefit is quantified) is rated as met if any information or presentation was included in the consent form (for example: “In general, pain relief will be achieved.”). The information was not checked for completeness or factual accuracy.

eTable. Evaluation sheet for the content analysis of consent forms used in Germany.

| Topic: | Code: | |||

| Meta-information | Yes | Partly | No | Comments |

| Author of the information – Institution or company is named. – Authors are named. If no authors are named: – Scientific or medical advisers are named. | – – – | |||

| Topicality – Date of issue is given. | – | |||

| Information sources – Information sources are listed. If yes: – Allocation of the information sources is possible. – Explanations of the information sources are provided (e.g., selection, evidence base, quality). | – – – | |||

| Objectives – Any objective of the consent form is listed. The objective listed is: – Preparation for the pre-operation discussion. – Support for a decision in favor of or against consenting to the procedure. – Enabling the patient to make an informed decision. – Documentation of the pre-operation discussion. | – – – – – | |||

| Signature It is possible to document, that the patient – consents to having the procedure, – refuses to have the procedure, – has received information, – has read the consent form, – has understood the information, – waives their right to receiving the information, – had enough time to consider their decision, – pays attention to behavioral rules/is able to pay attention. | – – – – – – – – | |||

| Contents Explanations are given on: | Yes | Partly | No | Comments |

| Type, extent, and undertaking of the intervention | – | |||

| Preparation and follow-up, including possible impairments/restrictions (e.g., nil by mouth, fitness to drive, ability to work) | – | |||

| Further therapeutic/diagnostic measures, that (may) result from the present intervention (e.g., reoperation) | – | |||

| Alternatives – Option of doing nothing/watchful waiting. – Additional treatment options. | – – | |||

| Only for diagnostic procedures: Test effectiveness – Is described verbally. – Numerical data (sensitivity, specificity, predictive values). | – – | |||

| Benefit of the intervention regarding patient relevant endpoints (mortality, morbidity, quality of life) – Endpoints are named. – Benefits are described in comparison with a different option. – The probability of a benefit is quantified (verbally or numerically). | – – | |||

| Harms/risks of the intervention regarding patient relevant endpoints (mortality, morbidity, quality of life) – Endpoints are named. – Harms are described in comparison with a different option. – The probability of harm is quantified (verbally or numerically). | – – | |||

| How the information is presented | Yes | Partly | No | Comments |

| Presentation of frequencies/rates of benefits and harms – Frequencies/rates are presented by using verbal descriptors. – Frequencies/rates are presented by using numerical descriptors. (percentages or natural frequencies) If numerical descriptors are used: – The same reference values are used. If benefits and/or harms are quantified in comparison with a control intervention (numerical): – Measures of relative risk are used. – Measures of absolute risk are used. | – | |||

| Language – Technical terms are used. – Explanations are given for technical terms used. – Directive language is used. | – | |||

| Supplementary materials (films, 3D models, or multimedia modules) | Yes | Partly | No | Comments |

| Films – Are available. – It is noted on the consent form whether the patient has received such material. If supplementary materials are used, they include the following topics: – Disease pattern. – Processes. – Risk communication. | – – – – – |

The evaluation sheet was piloted and revised. Evaluations were done independently by two persons (JL, AS). Differences were resolved by discussion.

The data entered (by JL) into the statistics software package SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24) were checked by a second person (SKM). The results were shown descriptively for the entire sample, so no conclusions could be drawn for the consent forms of individual providers.

Results

In January 2016 we identified and contacted eight publishers nationwide; three did not distribute their own consent forms at that time, one did not have a consent form on any of our chosen topics, and another refused participation for business related reasons. Three publishers participated and provided a total of 27 consent forms. We did not identify any medical association that offered consent forms on our predefined topics.

In Hamburg we contacted a total of 108 practices and hospitals. 19 out of 44 gastroenterology practices used consent forms for colonoscopy that differed from the forms we had already included from publishers. Three of these practices did not make their forms available, five duplicates and a sheet containing information only were excluded; we were therefore able to include 10 further forms. Eight of these had been devised by the practices themselves and two had been obtained from pharmaceutical companies. We were not able to include any additional forms relating to the other topics as the practices used the forms provided by the publishers.

In total, 37 consent forms were included in the content analysis: colonoscopy (n=13), mastectomy (n=2); PEG (n=3), cholecystectomy (n=3), TEP of the knee (n=3), disc prosthesis (n=2), PCI (n=3), stent prosthesis in aortic aneurysm (n=2), tonsillectomy (n=3), and cesarean section (n=3).

Table 2 shows the complete results of the content analyses. All informed consent forms under study described the intervention itself, and most of them (34 out of 37) also described preparations for the procedure and follow-up care. This is particularly successful if film clips are provided as supplementary information. Potential risks and complications were named and quantified in all consent forms. 30 forms contained information about the benefits of the intervention. Alternative treatment options were named in 26 forms, benefits and harms of the intervention were rarely described in comparison with these options (in 6 each out of 37). All forms used verbal descriptors to explain rates/frequencies; 10 forms also provided at least one numerical descriptor. Effect measures, such as for example the absolute risk reduction, were not provided. Transparency criteria were only met to a limited extent. All 37 forms give information on the author, publisher, or responsible practice. But only 17 or the 37 forms gave the actual author’s name and 21 the date of their issue. None of the forms included a reference list or description of the sources used.

Table 2. Results of content analysis of informed consent forms used in Germany.

| Item | Criteria |

n/N sheets* |

|

1. Authors of the information |

– Institution/company is named. – Explanation of the information sources are provided. – If no authors are named, scientific/medical advisers are named. | 37/37 17/37 6/20 |

| 2. Topicality | Date of issue is given. | 21/37 |

| 3. Information sources | – Information sources are listed. – If yes… … allocation of the information sources is possible, … explanation of the information sources are provided. | 0/37 –– |

| 4. Objectives | – Any objective of the consent form is listed. – The objective listed is… … preparing the patient for the pre-operation discussion, … supporting a decision in favor of or against consenting to the procedure, … enabling the patient to make an informed decision, … documentation of the pre-operation discussion. | 28/37 27/28 18/28 0/28 15/28 |

| 5. Signature | It is possible to document that the patient… … consents to having the procedure, … refuses to have the procedure, … has received information, … has read the consent form, … has understood the information, … waives their right to receiving information, … had enough time to consider their decision, … pays attention to behavioral rules/is able to pay attention. | 37/37 29/37 34/37 21/37 12/37 7/37 23/37 20/37 |

| 6. Intervention | Explanations are given on the type, extent, and undertaking of the intervention. | 37/37 |

| 7. Preparation and follow-up | Explanations are given on preparation and follow-up, including possible impairments/ restrictions (e.g., nil by mouth, fitness to drive, or fitness to work). | 34/37 |

| 8. Further measures | Explanations are given on further therapeutic/diagnostic measures, that (may) result from the present intervention, e.g., reoperations. | 34/37 |

| 9. Alternatives | – The option of doing nothing/watchful waiting is mentioned. – Additional treatment options are listed. | 4/37 26/37 |

| 10. Test effectiveness | Only for diagnostic procedures (n = 16): – The test effectiveness is described verbally. – Numerical descriptions are given of sensitivity, specificity, and/ or predictive values. | 7/16 1/16 |

| 11. Benefits | – Endpoints are named. – Benefits are (partly) described in comparison with a different option. – The probability of a benefit is quantified (verbally or numerically). | 30/37 6/30 23/30 |

| 12. Harms | – Endpoints are named. – Harms are (partly) described in comparison with a different option. – The probability of harm is quantified (verbally or numerically). | 37/37 6/37 37/37 |

| 13. Presentation of frequencies/rates of benefits and harms | – Frequencies/rates are presented (partly) by using verbal descriptors. – Frequencies/rates are presented (partly) by using numerical descriptors (percentages or natural frequencies). – If more than one numerical descriptor is used, the same reference values are used. – If benefits and harms are quantified in comparison with a control intervention … … measures of relative risk are used, … measures of absolute risk are used. | 37/37 10/37 1/4 – – |

| 14. Language | – Technical terms are used. – Explanations are given for technical terms used. – Directive language is (partly) used. | 37/37 37/37 4/37 |

| 15. Supplementary materials | – Supplementary materials are available (films). – It is noted on the consent form whether the patient has received such materials. – If supplementary materials are used, they (partly) include the following topics: – Disease pattern – Processes – Risk communication | 6/37 3/6 5/6 6/6 1/6 |

* Proportion of consent forms (n/N), that meet or partly meet the respective criterion.

Discussion

Our systematic review summarizing the evidence of the quality of the content of informed consent forms shows that the evaluation criteria used in the included content analyses are heterogeneous and do not—or only partly—meet the criteria for evidence-based health information. This means that a comprehensive evaluation of the quality of consent forms with regard to supporting an informed decision is not possible. However, on the basis of the criteria applied alone, the content analyses indicate occasionally grave shortcomings owing to lacking information.

Our analysis of the consent forms currently in use in Germany also shows that these forms are not suitable for supporting an informed decision. It was possible only to a limited extent to evaluate the information as regards topicality and reliability. No supporting information was given for weighing up different treatment options, as a numerical explanation of benefits and harms compared with alternative measures is lacking.

The present study has a number of strengths, but it also has limitations. The entire study is limited to written materials, although legally the pre-procedure discussion is binding and consent forms are only complementing the discussion (1, 8). It is often difficult to remember what was said in a pre-procedure discussion (7), and the perception of what topics were touched on may differ among the parties involved (29). For this reason, the role of written information in the patient education process is being discussed internationally too, and its importance regarding legal protection and regarding their use as a basis for dialogue and discussion is emphasized (7, 30).

The international evidence was reviewed systematically. No checklist was identified for evaluating the quality of the content analyses included, and for this reason we had to restrict ourselves to describing the methods.

We predefined evaluation criteria for analyzing the consent forms used in Germany. In doing so we considered central aspects of the criteria for evidence-based health information and informed decision-making (10, 11, 31, 32). No validated instruments exist for evaluating informed consent forms. The fact that no representative sample was drawn from all available consent forms may be a limitation. However, as we included commercial providers from all over Germany and as their consent forms on different topics were comparable in their quality, we assume that our results are generalizable—especially as hospitals often make use of the commercial products on offer.

Patients have a right to comprehensive and comprehensible information in order to make an informed decision in favor of or against consenting to a medical intervention (8, 9). To meet this requirement, evidence-based information should form the basis of the informed consent process. Written materials cannot replace the actual dialogue, but they can complement and support discussions. In this setting, the information should be adapted to the target audience if possible and should—if required—be available in a patient’s mother tongue (11). The results of our study show that the consent forms we investigated do not meet the requirements that should be mandatory for evidence based information and that new standards are needed. What needs to be discussed is the role that informed consent forms have in patients’ informed decision-making compared with evidence-based health information. It needs to be clarified what is meant by informed consent. Informed consent can refer to the entire process, starting with defining the indication, which can lead to an informed decision in favor of or against the intervention. However, informed consent can also be understood as a formal activity that happens after an informed decision in favor of the intervention has been made. For both variants, existing structures need to be questioned and strategies developed to ensure that patients’ entitlement to reliable information and participatory decision making can be put into practice.

Key Messages.

Patients are ethically and legally entitled to make an informed decision in favor of or against consenting to a medical intervention.

International studies have shown that patients do not sufficiently understand—or are able to explain—the contents of such consent forms.

Internationally, content analyses of consent forms have indicated grave deficiencies in terms of lacking information and inadequate risk communication.

The analysis of the patient consent forms currently in use in Germany shows that the evaluation of the information with regard to topicality and reliability is possible to a limited degree only, and that weighing up different treatment options is not supported by a numerical description of benefits and harms.

New standards are needed for informed consent, so that evidence-based information can become the basis for the information process and the requirement for informed decision-making can be met.

eBox 1. Evidence for the quality of the content of consent forms—methods.

Systematic review of the evidence for the quality of the content of consent forms, reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement (13)

Systematic literature searches

In January of 2016 we conducted systematic literature searches in the databases PubMed, PSYNDEX, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PEDro, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (search terms, see eBox 2). Updates were considered up to 02/2017. Additionally we searched the reference lists of relevant articles, conducted further Internet searches for content analyses of German-language consent forms, and contacted publishers in Germany for studies of their consent forms.

We included content analyses relating to the completeness and presentation of (meta-) information in informed consent forms for medical interventions. We excluded studies that only investigated comprehensibility on the basis of readability indices, consent forms for study participation, or non-standardized forms. We checked titles and abstracts first, followed by full text articles, with regard to our inclusion criteria. The selection was made independently by two persons (JL, AS). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data synthesis

To critically appraise the quality of the content analyses we applied the methodology used for selecting a sample, for deriving the criteria used, and for approaching the content analysis, in accordance with the CASP checklist for qualitative studies (14).

In order to evaluate the quality of consent forms with regard to supporting informed decision-making we defined criteria that are derived from the current guidelines for establishing evidence-based health information (10, 11). The criteria address meta-information (details of authors, topicality, information sources, objectives of the consent form, documentation options), contents (details on the intervention, alternatives, and benefits and harms), and the presentation (presentation of frequencies/rates, language). The evaluation criteria used in the content analyses were extracted and matched to these criteria.

Finally we extracted the results of the content analyses. Further results from the studies—for example, results of accompanying surveys or readability indices—were not considered. The data synthesis was done descriptively because of the heterogeneity of the included studies. JL developed study fact sheets (SFS) for all included studies and AS checked the included data. The SFS can be accessed on the project website (www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/projekte/aufklaerungsboegen.html).

eBox 2. Search terms.

(“consent form“ OR “consent forms“ OR “informed consent form“ OR “informed consent forms“ OR “informed consent documents“ OR “informed consent document“ OR “Patient Education as Topic“ [Mesh] OR “Patient Education Handout“ [Publication Type] OR “Communications Media“ [Mesh] OR “Decision Support Techniques“ [Mesh] OR “Decision Support Systems, Clinical“ [Mesh] OR “Consumer Health Information“ [Mesh] OR “health information“ OR “patient education“ OR “patient information“ OR “decision aid“ OR “decision board“ OR “information material“ OR brochure OR leaflet OR pamphlet OR flyer OR presentation)

AND

(“informed consent“ OR “Informed Consent“ [Mesh])

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

We thank Susanne Kählau-Meier for her help with recruitment, sourcing of literature, and data control.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Bundesärztekammer. (Muster-)Berufsordnung für die in Deutschland tätigen Ärztinnen und Ärzte - MBO-Ä 1997 - in der Fassung des Beschlusses des 118. Deutschen Ärztetages 2015 in Frankfurt am Main. Dtsch Arztebl. 2015;112 A-1348. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberlandesgericht (OLG) Köln. Urteil vom 26. Oktober 2011 (Az. 5 U 46/11) www.openjur.de/u/451468.html (last accessed on 26 September 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberlandesgericht (OLG) Hamm. Urteil vom 18. Juni 2013 (AZ. 26 U 85/12) www.openjur.de/u/645241.html (last accessed on 26 September 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eltorai AE, Naqvi SS, Ghanian S, et al. Readability of invasive procedure consent forms. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8:830–833. doi: 10.1111/cts.12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loughran D. Surgical consent: the world‘s largest Chinese whisper? A review of current surgical consent practices. Med Ethics. 2015;41:206–210. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2013-101931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepeau AE, McKinney BI, Fox-Ryvicker M, Castelli J, Penna J, Wang ED. Prospective evaluation of patient comprehension of informed consent. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherlock A, Brownie S. Patients‘ recollection and understanding of informed consent: a literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:207–210. doi: 10.1111/ans.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Rechte von Patientinnen und Patienten. Bundesgesetzblatt online, Bürgerzugang. Bundesanzeiger Verlag. 2013. www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?start=//*%5B@attr_id=%27bgbl113s0277.pdf%27%5D#__bgbl__%2F%2F*%5B%40attr_id%3D%27bgbl113s0277.pdf%27%5D__1521727653082 (last accessed on 26 September 2017) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_index.asp (last accessed on 26 September 2017) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arbeitsgruppe GPGI Deutsches Netzwerk Evidenzbasierte Medizin e.V. Gute Praxis Gesundheitsinformation. [Good practice guidelines for health information]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2016:110111–85-92. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lühnen J, Albrecht M, Mühlhauser I, Steckelberg A. www.leitlinie-gesundheitsinformation.de/ (last accessed on 26 September 2017) Hamburg: 2016. Leitlinie evidenzbasierte Gesundheitsinformation. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lühnen J, Mühlhauser I, Steckelberg A. Aufklärungsbögen heute Studienprotokoll. www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/projekte/aufklaerungsboegen.html (last accessed on 26 September 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) CASP Qualitative Checklist. www.casp-uk.net/checklists (last accessed on 26 September 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottrell MM, Alpert H, Fischbach RL, Emanuel LL. Hospital informed consent for procedure forms: facilitating quality patient-physician interaction. Arch Surg. 2000;135:26–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briguglio J, Cardella JF, Fox PS, Hopper KD, TenHave TR. Development of a model angiography informed consent form based on a multiinstitutional survey of current forms. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:971–978. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durfy SJ, Buchanan TE, Burke W. Testing for inherited susceptibility to breast cancer: a survey of informed consent forms for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation testing. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75:82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenstaedt RS, Glanz K, Smith DG, Derstine T. Informed consent for blood transfusion: a regional hospital survey. Transfusion. 1993;33:558–561. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33793325050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glick A, Taylor D, Valenza JA, Walji MF. Assessing the content, presentation, and readability of dental informed consents. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:849–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopper KD, Lambe HA, Shirk SJ. Readability of informed consent forms for use with iodinated contrast media. Radiology. 1993;187:279–283. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.1.8451429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaz BH, Demmons DG, Hillyer CD. Critical evaluation of informed consent forms for adult and minor aged whole blood donation used by United States blood centers. Transfusion. 2009;49:1136–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krahn TM, Baylis F. A review of consent documents from canadian IVF clinics, 1991 to 2014. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cattapan AR. Good eggs? Evaluating consent forms for egg donation. J Med Ethics. 2016;42:455–459. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2015-102964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown H, Ramchandani M, Gillow JT, Tsaloumas MD. Are patient information leaflets contributing to informed consent for cataract surgery? J Med Ethics. 2004;30:218–220. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery BS, Venn SN, Beard RC. Written information for transurethral resection of the prostate—-a national audit. Br J Urol. 1995;75:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gargoum FS, O‘Keeffe ST. Readability and content of patient information leaflets for endoscopic procedures. Ir J Med Sci. 2014;183:429–432. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-1033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vucemilo L, Borovecki A. Readability and content assessment of informed consent forms for medical procedures in Croatia. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138017. e0138017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ezeome ER, Chuke PI, Ezeome IV. Contents and readability of currently used surgical/procedure informed consent forms in Nigerian tertiary health institutions. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14:311–317. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.86775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman M, Arja W, Batra R, et al. Informed consent for blood transfusion: What do medicine residents tell? What do patients understand? Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:559–565. doi: 10.1309/AJCP2TN5ODJLYGQR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirby R, Challacombe B, Hughes S, Chowdhury S, Dasgupta P. Increasing importance of truly informed consent: the role of written patient information. BJU Int. 2013;112:715–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bunge M, Mühlhauser I, Steckelberg A. What constitutes evidence-based patient information? Overview of discussed criteria. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steckelberg A, Berger B, Köpke S, Heesen C, Mühlhauser I. Kriterien für evidenzbasierte Patienteninformationen [Criteria for evidence-based patient information] Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 2005;99:343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]