Abstract

Introduction

Traumatic hip dislocation is a severe injury with the potential for significant morbidity and mortality. Bilateral hip dislocation is rare representing 1.25% of all hip dislocations.

Presentation of the case

A 19-year-old male had a high-speed motor vehicle accident. After stabilizing the patient, it was noticed that the position of the right lower limb was in adduction and internal rotation while the left was in external rotation and abduction. Pelvis x-ray showed right superior posterior and left anterior inferior hip dislocations. Closed reduction was performed within 3 hours from the trauma for both sides. The post reduction CT scan showed adequate reduction of both hips with no associated fractures. During his three-year follow-up, he never had any complaints and the clinical examination and radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities.

Discussion

Early reduction of hip dislocations minimizes the risk of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. The current recommendations state that a hip dislocation must be reduced within 6 hours.

Conclusion

This is a rare case of bilateral asymmetric hip dislocations with no concomitant fractures. It is important to reduce hip dislocation within 6 hours from the time of injury to prevent osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Keywords: Hip dislocation, Bilateral, Asymmetric, Traumatic, Case report

Highlights

-

•

A 19-year-old male had a high-speed MVA.

-

•

He sustained bilateral asymmetric hip dislocations.

-

•

No fractures were identified on the CT.

-

•

Closed reduction was performed in both sides.

-

•

The outcome after a three-year-follow up is presented.

1. Introduction

Traumatic hip dislocation is a severe injury with the potential for significant morbidity and mortality. The cause is almost always traumatic and usually associated with motor vehicle accidents. Posterior dislocation is the most common type constituting 85–90% of hip dislocations [1].

Bilateral hip dislocation is a rare injury representing 1.25% of all hip dislocations [2]. Asymmetrical dislocations are even more rare accounting for approximately 0.01–0.02% of all joint dislocations [3]. Careful trauma evaluation is important in order to rule out common associated injuries that may lead to a long-term morbidity. Early reduction within 6 hours is the mainstay management to prevent the complication of avascular necrosis (AVN) [1].

In this article, we present a rare case of asymmetric dislocations of the hips with no associated fractures in a young man and the outcome after a three-year follow-up. This case report adds to the scarce existing data about bilateral hip dislocation including the mechanism, clinical and radiographic findings and outcome. The article was reported in line with the SCARE criteria [4].

2. Case report

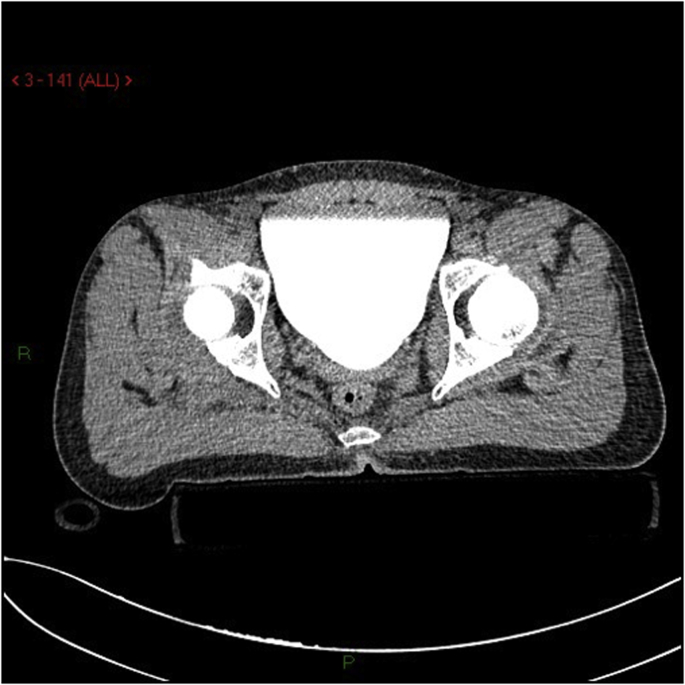

A 19-year-old man, with no known medical illnesses, was brought by ambulance to the emergency room at our community hospital following high-speed collision into another vehicle. On arrival, ATLS protocol was carried out. Although the primary survey showed a patent airway with good bilateral air entry, the patient was in respiratory distress. Chest x-ray showed right pneumothorax. An intercostal tube was inserted by the thoracic surgeon. His vital signs were stable at that time. Pelvis x-ray showed right superior posterior and left anterior inferior hip dislocations (Fig. 1). The position of the right lower limb was in adduction and internal rotation while the left was in external rotation and abduction. The patient had intact motor function, sensation, and pulses distally throughout the lower and upper extremities. Chest, abdomen and pelvis CT scan was done revealing right pneumothorax, right posterior hip dislocation and left anterior hip dislocation with no obvious fractures (Fig. 2). Under conscious sedation, closed reduction was performed within 3 hours from the trauma for both hip dislocations. After reduction, both hips were noted to be stable throughout the range of motion with intact distal neurovascular status. The post reduction radiographs (Fig. 3) and CT scan (Fig. 4) showed adequate reduction of both hips with no associated fractures. The patient was admitted in the trauma ward and kept in skin traction for both hips for 6 weeks as requested by one of the senior trauma surgeons involved in his care but there was no clear indication from the orthopedic surgeons perspectives. He was given analgesia and antithrombotic medications during his stay. He was discharged on the 6th week after he became able to fully weight bear. During his three-year follow-up, he never had any complaints and the clinical examination and radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

Pre-reduction x-ray.

Fig. 2.

Pre-reduction CT scan.

Fig. 3.

Post-reduction x-ray.

Fig. 4.

Post-reduction CT scan.

Fig. 5.

X-ray at final follow up.

3. Discussion

Hip dislocation is more common among young male patients [3]. It usually occurs due to motor vehicle accidents resulting in a severe deceleration force to a flexed knee; associated injuries are acetabular fractures and knee injuries [2].

Posterior hip dislocations are sustained in dashboard injuries as the force toward the knee is directed posteriorly while the hip is in flexion position. Anterior hip dislocations, representing approximately 11% of all hip dislocations, usually result when the hip is forced into abduction and external rotation. In this regard, fractures of the femoral head and shaft may occur in such circumstances [2,5]. Suggestive findings on examination include shortening, internal rotation, and adduction of the lower limb which is associated with posterior hip dislocation. On the other hand, a flexed, abducted, and externally rotated lower limb indicates an anterior inferior dislocation [6].

Pelvic radiographs should be done in the multiple-trauma patient as part of the ATLS protocol especially when clinical findings are suggestive of hip dislocation. Judet views are useful for identifying associated acetabular fractures [7]. CT scan of the hip is usually not necessary prior to reduction but few cuts can be obtained in a multiple-trauma patient who has other indications for a CT scan. This is especially emphasized in anterior dislocation of the hip as plain radiographs may only show a difference in the femoral size as the only diagnostic clue. Post reduction CT plays an important role in the evaluation of intra-articular osteochondral fragments and planning of definitive surgical treatment for associated acetabular fractures [6]. The mainstay management is early diagnosis and reduction of hip dislocations as the risk of osteonecrosis of the femoral head is significantly affected by the time elapsed prior to the reduction. The current recommendations state that a dislocated hip must be reduced within the first 6 hours from the time of injury [1,8].

The incidence of Osteonecrosis is 6–27% following hip dislocation [9,10]. Osteonecrosis is more common to occur in posterior hip dislocations (7.5%) than anterior dislocations (1.5%) and central dislocations (1.6%) [11]. The most common presenting symptom of Osteonecrosis is pain. Standard hip radiographs, MRI or radionuclide bone scans can be performed to evaluate for osteonecrosis [12,13].

Post-traumatic arthritis is a known complication of hip dislocation [1]. Risk Factors of post-traumatic arthritis include femoral head fractures, acetabular fractures, nonconcentric reduction, delay time prior to reduction and osteonecrosis [14].

Neurovascular injuries may occur in hip dislocations. Nerve injury can be early due to compression from the femoral head or fracture fragment or late by heterotopic ossification. The sciatic nerve is the most commonly injured nerve in 10% of the patients following posterior hip dislocation. The peroneal branch is most often affected. Although rare, injury to the femoral neurovascular bundle can occur as a result of anterior dislocations [2,15]. Thus, careful sensory and motor neurological evaluation before and after reduction is paramount. Recovery of function in sciatic nerve injury, either partial or complete, occurs in 60–70% of patients [16].

Similar cases of bilateral asymmetric hip dislocation have been reported in the literature; however, unlike in our case, the majority of them were associated with fractures of the acetabular walls [[17], [18], [19]].

In conclusion, bilateral hip dislocation is a rare injury and usually associated with high-speed motor vehicle accidents. Prompt and thorough assessment is necessary. In order to minimize the risk of osteonecrosis of the hips, the reduction should be performed within the first 6 h from the time of injury. Furthermore, a neurovascular examination should be conducted before and after the reduction.

Disclaimer

This version had been read by all the authors who also bear responsibility for it. The material presented is original and all authors agreed upon their inclusion. This manuscript has neither been published nor submitted to another journal.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

None.

Sources of funding

None.

Author contribution

AA: drafting the manuscript, reviewing and approving the final version.

BA: collecting the data, preparing the manuscript.

IA: collecting the data, reviewing the final version.

SA: revising the manuscript, preparing and submitting the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Research registration number

Researchregistry3034.

Guarantor

Ahmed Alshammari.

References

- 1.Sanders S., Tejwani N., Egol K.A. Traumatic hip dislocation–a review. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2010;68(2):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips A.M., Konchwalla A. The pathologic features and mechanism of traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;377:7–10. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckwalter J., Westerlind B., Karam M. Asymmetric bilateral hip dislocations: a case report and historical review of the literature. Iowa Orthop. J. 2015;35:70–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A. The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34(Supplement C):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehtisham S.M. Traumatic dislocation of hip joint with fracture of shaft of femur on the same side. J. Trauma. 1976;16(3):196–205. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks R.A., Ribbans W.J. Diagnosis and imaging studies of traumatic hip dislocations in the adult. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;377:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kool D.R., Blickman J.G. Advanced trauma life Support®. ABCDE from a radiological point of view. Emerg. Radiol. 2007;14(3):135–141. doi: 10.1007/s10140-007-0633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang E.C., Cornwall R. Initial treatment of traumatic hip dislocations in the adult. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;377:24–31. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso J.E. A review of the treatment of hip dislocations associated with acetabular fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;377:32–43. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brav E.A. Traumatic dislocation of the hip: army experience and results over a twelve-year period. JBJS. 1962;44(6):1115–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letournel E., R J. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1981. Fractures of the Acetabulum. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manenti G. The role of imaging in diagnosis and management of femoral head avascular necrosis. Clin. Cases Mineral Bone Metabol. 2015;12(Suppl 1):31–38. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2015.12.3s.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan K., Mok C. Glucocorticoid-induced avascular bone necrosis: diagnosis and management. Open Orthop. J. 2012;6:449–457. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Merchan E.C. Coxarthrosis after traumatic hip dislocation in the adult. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;377:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erb R.E. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip: spectrum of plain film and CT findings. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1995;165(5):1215–1219. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.5.7572506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornwall R., Radomisli T.E. Nerve injury in traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;377:84–91. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Sanchez M., Kovacs-Kovacs N. Bilateral asymmetric traumatic hip dislocation in an adult. J. Emerg. Med. 2006;31(4):429–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uslu M. Combined bilateral asymmetric hip dislocation and anterior shoulder dislocation. World J. Emerg. Med. 2012;3(4):311–313. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sah A.P., Marsh E. Traumatic simultaneous asymmetric hip dislocations and motor vehicle accidents. Orthopedics. 2008;31(6):613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]