Biofilms play an important role in the Vibrio cholerae life cycle, contributing to both environmental survival and transmission to a human host. Identifying key regulators of V. cholerae biofilm formation is necessary to fully understand how this important growth mode is modulated in response to various signals encountered in the environment and the host. In this study, we characterized the role of RRs that function as coactivators of RpoN in regulating biofilm formation and identified new components in the V. cholerae biofilm regulatory circuitry.

KEYWORDS: Vibrio cholerae, VPS, NtrC, biofilm

ABSTRACT

The biofilm growth mode is important in both the intestinal and environmental phases of the Vibrio cholerae life cycle. Regulation of biofilm formation involves several transcriptional regulators and alternative sigma factors. One such factor is the alternative sigma factor RpoN, which positively regulates biofilm formation. RpoN requires bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs) to initiate transcription. The V. cholerae genome encodes seven bEBPs (LuxO, VC1522, VC1926 [DctD-1], FlrC, NtrC, VCA0142 [DctD-2], and PgtA) that belong to the NtrC family of response regulators (RRs) of two-component regulatory systems. The contribution of these regulators to biofilm formation is not well understood. In this study, we analyzed biofilm formation and the regulation of vpsL expression by RpoN activators. Mutants lacking NtrC had increased biofilm formation and vpsL expression. NtrC negatively regulates the expression of core regulators of biofilm formation (vpsR, vpsT, and hapR). NtrC from V. cholerae supported growth and activated glnA expression when nitrogen availability was limited. However, the repressive activity of NtrC toward vpsL expression was not affected by the nitrogen sources present. This study unveils the role of NtrC as a regulator of vps expression and biofilm formation in V. cholerae.

IMPORTANCE Biofilms play an important role in the Vibrio cholerae life cycle, contributing to both environmental survival and transmission to a human host. Identifying key regulators of V. cholerae biofilm formation is necessary to fully understand how this important growth mode is modulated in response to various signals encountered in the environment and the host. In this study, we characterized the role of RRs that function as coactivators of RpoN in regulating biofilm formation and identified new components in the V. cholerae biofilm regulatory circuitry.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the severe diarrheal disease cholera, can inhabit freshwater, estuaries, and human intestines. In its natural aquatic environment, V. cholerae can be found either as free-swimming planktonic cells or as biofilm-associated cells attached to surfaces (1). The ability of V. cholerae to form biofilms is critical for its survival in its natural habitats and transmission to the human host. The production of mature biofilms by V. cholerae requires extracellular matrix components. A major component of the V. cholerae biofilm matrix is the exopolysaccharide (EPS) Vibrio polysaccharide (VPS), which is required for the formation of three-dimensional biofilm structures (2, 3).

The regulatory network that controls biofilm formation is complex and involves several transcriptional regulators and alternative sigma factors. The primary components of this network consist of two positive transcriptional regulators, VpsT and VpsR, and three negative transcriptional regulators, HapR, cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP), and histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) (4–10). In addition to the main biofilm regulators, VpsR and VpsT, a number of other response regulators (RRs) have been identified to impact V. cholerae biofilm formation, including the positive regulators LuxO and VxrB and the negative regulators PhoB, CarR, VarA, and VieA (4, 5, 11–18). These RRs may affect biofilm formation through interactions with other key regulators or through the direct regulation of biofilm genes. The alternative sigma factors RpoS and RpoN also feed into the V. cholerae biofilm regulatory circuitry (6).

RpoN positively regulates biofilm formation and vpsL gene expression in V. cholerae (6). RpoN-dependent gene expression requires an activator, as RpoN is unable to initiate transcription by itself. Such regulators are classified as bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs) (19). One group of bEBPs belongs to the NtrC family of RRs, named after its best-characterized representative, nitrogen regulatory protein C (NtrC) from Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (20–22). The contribution of the NtrC family regulators to the RpoN-mediated biofilm phenotype is not well characterized. NtrC family RRs have an N-terminal receiver (REC) domain, a central AAA+ ATPase domain, an RpoN-binding domain, and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain. The V. cholerae genome is predicted to have seven genes encoding NtrC family RRs VC1021 (luxO), VC1522, VC1926 (dctD-1), VC2135 (flrC), VC2749 (ntrC), VCA0142 (dctD-2), and VCA0704 (pgtA) (see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Complete_Genomes/RRcensus.html and http://www.p2cs.org/).

In this study, we determined the regulatory role of the NtrC family RRs in biofilm formation and in the expression of vps genes. Consistent with data from previous studies, we found that LuxO positively regulates biofilm formation and that FlrC negatively regulates biofilm formation (23, 24). Additionally, we determined that NtrC negatively regulates vpsL gene expression and biofilm formation. NtrC from V. cholerae supports growth in poor nitrogen sources and is necessary to activate the expression of glnA, a gene that encodes glutamine synthetase, which is induced in response to nitrogen limitation. The expression of vpsL is downregulated by NtrC regardless of the nitrogen source available. Together, these results underscore the importance and complexity of the NtrC-dependent regulation of biofilm formation in V. cholerae.

RESULTS

NtrC family response regulators modulate biofilm formation and vpsL expression in Vibrio cholerae.

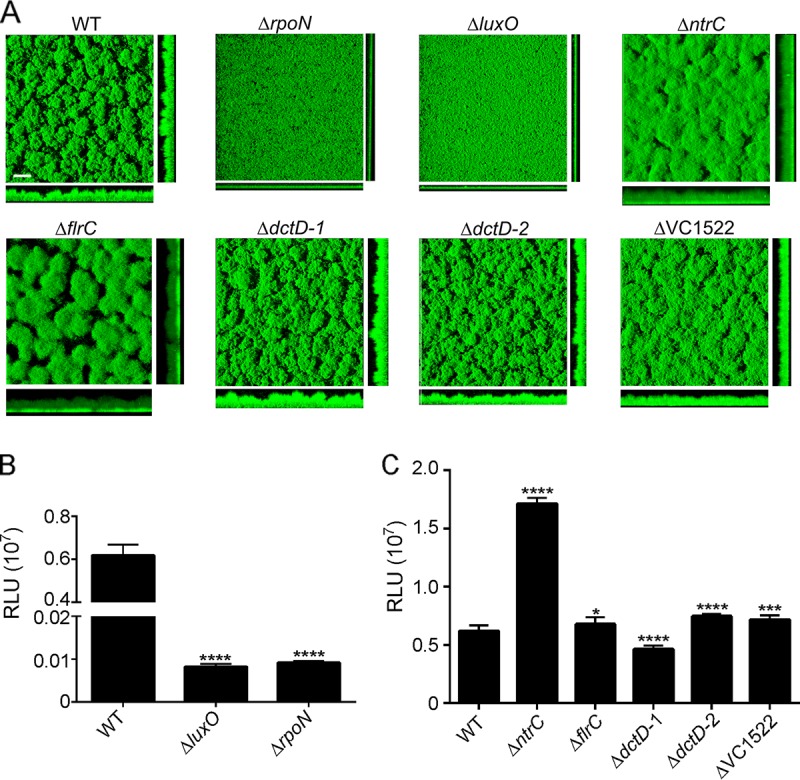

We have previously shown that RpoN is a positive regulator of biofilm formation in V. cholerae (6). As RpoN requires bEBPs to activate transcription, we sought to understand the contribution of bEBPs to the RpoN-mediated regulation of biofilm formation. For this study, we focused on NtrC family RRs. To determine if the seven genes predicted to encode NtrC RRs in V. cholerae contain a conserved phosphorylation site and the GAFTGA motif necessary to interact with RpoN, we performed a multiple-sequence alignment (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All these proteins have an aspartate residue that aligns with aspartate 56 from FlrC. This amino acid has been shown to be important for FlrC activity and is predicted to be the phosphorylation site (25). Furthermore, all proteins except for PgtA (VCA0704) had a conserved GAFTGA motif, which is required for the RpoN-dependent activation of target genes; for this reason, we excluded PgtA from further analysis. To evaluate the contribution of NtrC family regulators to the RpoN-mediated biofilm phenotype, we analyzed the biofilm formation capacities of strains lacking RpoN or the NtrC family RRs. After 48 h of incubation, the ΔrpoN and ΔluxO strains formed significantly less biofilm and lacked complete three-dimensional biofilm structures (Fig. 1A). COMSTAT analysis showed that the ΔrpoN and ΔluxO strains had ∼65% less biomass and ∼70% less average thickness than the wild type (WT) (Table 1). Other studies have shown that rpoN- and luxO-null mutants are deficient in biofilm formation; our results corroborated those data (6, 24, 26). Furthermore, we observed that the ΔntrC and ΔflrC strains made thicker biofilms than the wild type (Fig. 1A). COMSTAT analysis showed that the ΔntrC and ΔflrC strains made 32% and 27% more biomass, respectively, than the wild type and had 30% and 52% increases in average thickness, respectively, compared to the wild type (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Analysis of biofilm formation and vpsL expression in NtrC family RR deletion mutants. (A) Three-dimensional biofilm structures of V. cholerae wild-type (WT), ΔrpoN, ΔluxO, ΔntrC, ΔflrC, ΔdctD-1, ΔdctD-2, and ΔVC1522 strains after 48 h of incubation in flow cell chambers. Images of horizontal (xy) and vertical (xz) projections of biofilms are shown. The results shown are from one representative experiment of three independent experiments. Bar = 30 μm. (B) Expression of PvpsL-luxCADBE (pFY_0950) in the WT, ΔluxO, and ΔrpoN strains The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of relative light units (RLU) obtained from four technical replicates from two independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test was used to compare expression levels between the WT and deletion mutants. ****, P < 0.0001. (C) Expression of PvpsL-luxCADBE (pFY_0950) in the WT, ΔntrC, ΔflrC, ΔdctD-1, ΔdctD-2, and ΔVC1522 strains. The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of RLU obtained from four technical replicates from two independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test was used to compare expression levels between the WT and deletion mutants. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

TABLE 1.

COMSTAT analysis of biofilms of NtrC family ΔRR strains at 48 ha

| Strain | Mean biomass (μm3) (SD) | Mean avg thickness (μm) (SD) | Mean maximum thickness (μm) (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 17.1 (2.6) | 19.0 (2.6) | 22.1 (2.4) |

| ΔrpoN strain | 6.4 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.6) | 7.2 (0.9) |

| ΔluxO strain | 6.0 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.6) | 5.7 (0.6) |

| ΔntrC strain | 22.6 (0.6) | 25.3 (1.3) | 26.7 (2.5) |

| ΔflrC strain | 21.8 (0.6) | 29.0 (0.7) | 31.0 (1.9) |

| ΔdctD-1 strain | 13.5 (4.0) | 16.0 (0.8) | 23.9 (1.4) |

| ΔdctD-2 strain | 13.9 (1.3) | 17.0 (0.8) | 22.7 (5.2) |

| ΔVC1522 strain | 16.8 (1.9) | 19.5 (0.2) | 19.5 (0.2) |

The values are the means of data from six z-series image stacks.

The most abundant component of the V. cholerae biofilm matrix is the exopolysaccharide VPS. The biosynthesis of VPS is encoded in two operons, vps-I and vps-II (2, 4). In addition to biofilm formation, we also analyzed the expression of vps genes using the PvpsL-lux transcriptional reporter, where the promoter of the vps-II operon (PvpsL) is cloned upstream of the luciferase reporter encoded by luxCADBE in plasmid pBBRlux (pFY-0950). We then analyzed vpsL transcription in the wild type and mutants lacking RpoN or the NtrC family RRs. As previously reported, we found that vpsL transcription was abrogated in the ΔrpoN (6) and ΔluxO (27) strains (Fig. 1B). In agreement with its negative effect on biofilm formation, we observed that the absence of NtrC promotes a 3-fold upregulation of the expression of vpsL compared to the expression of this gene in the wild type. On the other hand, even though the absence of flrC showed a significant increase in biofilm formation, the absence of this regulator had only a modest effect on vpsL expression (∼10% increase) (Fig. 1C). The expression of vpsL was slightly reduced in the ΔdctD-1 strain (∼30% decrease) and modestly increased in the ΔdctD-2 (∼21% increase) and ΔVC1522 (∼16% increase) strains; however, none of these mutants showed an altered biofilm phenotype.

Collectively, these findings showed that LuxO is the only NtrC family RR that positively regulates both biofilm formation and vpsL expression; NtrC and FlrC negatively regulate biofilm formation, but NtrC has a much stronger effect on the downregulation of vpsL expression. We focused the rest of this study on the characterization of NtrC as a regulator of vps expression and biofilm formation in V. cholerae.

NtrC downregulates the core regulators of biofilm formation.

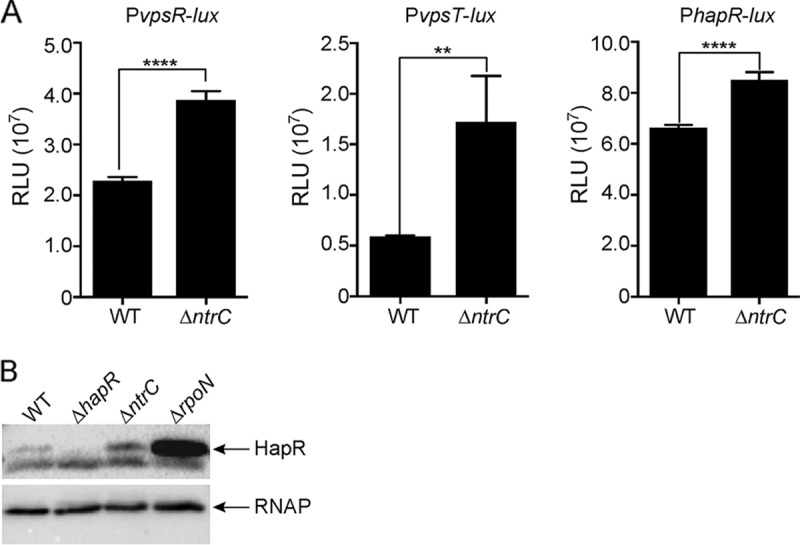

VpsR and VpsT are positive transcriptional regulators of vps genes, while HapR negatively regulates vps genes. To determine if NtrC regulates vpsR, vpsT, and hapR, we used transcriptional fusions to the luxCADBE reporter and determined the expression levels of these constructs in the ΔntrC strain compared to the wild type (Fig. 2A). The expression levels of vpsR and vpsT were increased 69% and 192%, respectively, in the ΔntrC strain compared to the wild type. The expression of hapR showed a 28% increase in the ΔntrC strain compared to the wild type. It is well known that hapR can be regulated at the posttranscriptional level through the quorum-sensing signaling pathway (17, 28). To evaluate the impact of NtrC on HapR production, we analyzed HapR levels. We found a small but reproducible increase in the HapR abundance in the ΔntrC strain; as expected, HapR levels were markedly increased in the ΔrpoN strain compared to the wild type (Fig. 2B). Together, these results suggest that NtrC acts upstream as a negative regulator of the positive regulators of biofilms. The fact that NtrC negatively regulates HapR was surprising due to the role of HapR as a negative regulator of biofilms.

FIG 2.

NtrC negatively regulates vpsR, vpsT, and hapR expression. (A) Expression of PvpsR-luxCADBE, PvpsT-luxCADBE, and PhapR-luxCADBE in the WT and ΔntrC strains at the exponential growth phase. The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of RLU obtained from three technical replicates from two independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. A two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch's correction was used to compare expression levels between the WT and deletion mutants. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) Western blot analysis of HapR production in the WT and ΔntrC strains during the exponential growth phase (OD600 of 0.3). Equal amounts of total protein (determined by a BCA assay) were loaded onto an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. The abundance of RNA polymerase (RNAP) was used as a loading control.

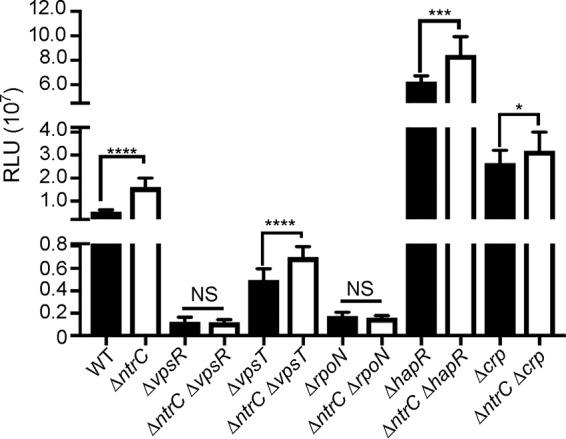

NtrC represses vpsL expression independently of VpsT, HapR, and CRP.

To determine the contribution of NtrC to the vps regulatory network, we characterized the genetic interaction between ntrC, vpsR, vpsT, rpoN, hapR, and crp (Fig. 3). As described above, the ΔntrC strain exhibited increased vpsL expression. The deletion of ntrC in backgrounds that lack either vpsR or rpoN did not result in increased vpsL expression, indicating that the positive effect of these regulators is dominant over the NtrC-mediated repression of vpsL. The expression of vpsL in these genetic backgrounds is severely diminished. The expression of vpsL in the absence of VpsT was reduced ∼91% compared to the wild type. The expression levels of vpsL in the ΔntrC ΔvpsT, ΔntrC ΔhapR, and ΔntrC Δcrp strains showed ∼40%, 35%, and 20% increases, respectively, compared to the levels in the individual mutants of these biofilm regulators (ΔvpsT, ΔhapR, and Δcrp) (Fig. 3). These findings suggest that NtrC can repress vpsL independently of VpsT, HapR, and CRP, but its negative effect is dependent on the presence of VpsR and RpoN.

FIG 3.

NtrC represses vpsL expression independently of regulators of biofilm formation, except for VpsR and RpoN. Shown are expression levels of PvpsL-luxCADBE (pFY_0950) in the WT, ΔntrC, ΔvpsR, ΔntrC ΔvpsR, ΔvpsT, ΔntrC ΔvpsT, ΔrpoN, ΔntrC ΔrpoN, ΔhapR, ΔntrC ΔhapR, Δcrp, and ΔntrC Δcrp strains. The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of RLU obtained from four technical replicates from at least three independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. Pairwise analysis was done by using a two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch's correction. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

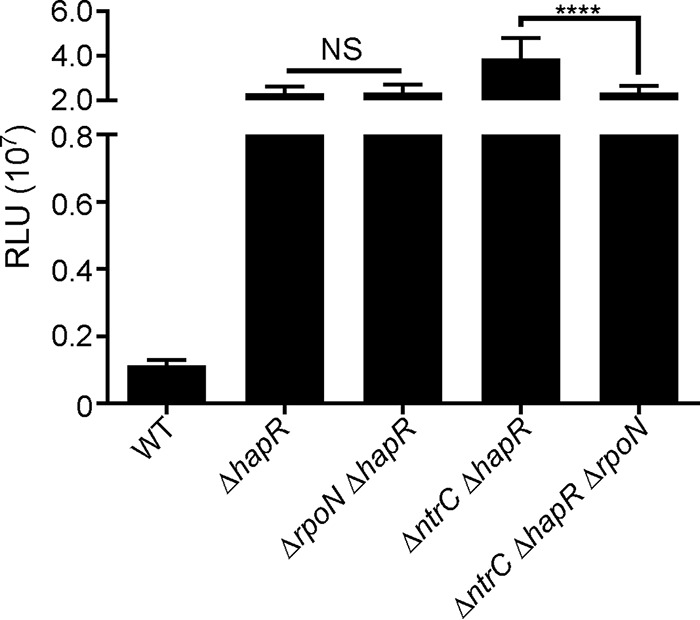

RpoN contributes to vpsL expression in the absence of NtrC and HapR.

To determine the contribution of RpoN to vpsL expression in the absence of HapR and NtrC, we characterized the genetic interaction between rpoN, ntrC, and hapR (Fig. 4). The expression levels of vpsL-lux in the ΔrpoN ΔhapR and ΔhapR strains were similar, indicating that the observed phenotype is likely due to increased HapR levels in the ΔrpoN strain. We found that the expression level of vpsL decreased significantly in the ΔntrC ΔhapR ΔrpoN strain compared to the ΔntrC ΔhapR strain, indicating that NtrC-dependent repression in the ΔhapR strain relies on the presence of rpoN.

FIG 4.

RpoN contributes to vpsL expression in the absence of NtrC and HapR. Shown are expression levels of PvpsL-luxCADBE (pFY_0950) in the WT, ΔhapR, ΔrpoN ΔhapR, ΔntrC ΔhapR, and ΔntrC ΔhapR ΔrpoN strains. The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of RLU obtained from four technical replicates from at least three independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test was used to compare expression levels between the WT and deletion mutants. ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

The absence of NtrC has no effect on c-di-GMP levels.

The expression of VPS biosynthetic genes and their regulators is controlled by the levels of the nucleotide-based second messenger cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP). High levels of c-di-GMP increase biofilm formation. We hypothesized that the effect of NtrC on vpsL, vpsR, and vpsT expression could be mediated through the modulation of the cellular c-di-GMP pool. We extracted nucleotides from exponentially grown wild-type and ΔntrC strain cultures and measured cellular c-di-GMP levels. We found no significant difference in the abundance of c-di-GMP in the ΔntrC strain compared to the abundance in the wild type, suggesting that the NtrC-mediated repression of vps expression is not due to changes in the cellular c-di-GMP levels under these conditions (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

V. cholerae NtrC supports growth under conditions of low nitrogen availability.

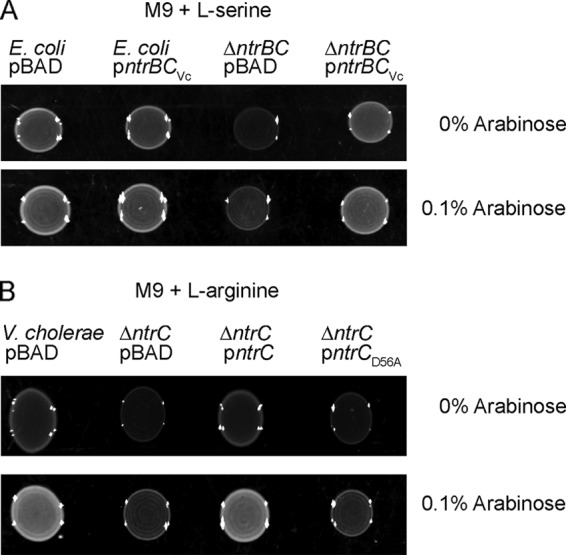

Amino acid sequence alignments of NtrC from V. cholerae to its counterparts in E. coli and S. Typhimurium showed that NtrC from V. cholerae is 73.12% and 72.9% identical to NtrC from E. coli and S. Typhimurium, respectively (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). To test if V. cholerae NtrC functions similarly to its counterpart in E. coli, we performed a complementation analysis using an E. coli strain lacking ntrB and ntrC (ΔntrBC). For these studies, we expressed V. cholerae ntrBC from an arabinose-inducible promoter on a pBAD plasmid (Fig. 5A) and analyzed its ability to support growth on M9 agar supplemented with a poor nitrogen source (l-serine). Wild-type E. coli containing the empty vector (pBAD) grew on this medium; however, the ΔntrBC strain containing the empty vector grew poorly, indicating that the ΔntrBC strain has a decreased ability to utilize l-serine as a nitrogen source (Fig. 5A). When V. cholerae ntrBC was introduced into the E. coli ΔntrBC strain, growth on M9 agar with l-serine was restored (Fig. 5A). These findings suggest that V. cholerae ntrC and ntrB function similarly to their E. coli counterparts.

FIG 5.

NtrC from V. cholerae allows growth under limiting nitrogen availability. (A) Images of spot colonies from E. coli and the ΔntrC strain harboring an empty plasmid (pBAD) or a complementation plasmid expressing ntrB-ntrC or ntrB-ntrCD56A from V. cholerae. Cells were grown on M9 agar supplemented with 100 mM l-serine as a nitrogen source and 0 or 0.1% arabinose (for induction) for 24 h at 37°C. (B) Images of spot colonies from V. cholerae and the ΔntrC strain harboring an empty plasmid (pBAD) or a complementation plasmid expressing ntrC or ntrCD56A. Cells were grown on M9 agar supplemented with 100 mM l-arginine as a nitrogen source and 0 or 0.1% arabinose for 24 h at 37°C.

Using the same approach, we analyzed the contribution of NtrC to supporting the growth of V. cholerae in the presence of another poor nitrogen source, l-arginine. In the absence of NtrC, V. cholerae grew poorly on M9 broth agar supplemented with l-arginine as the sole nitrogen source. When expressed in trans from an arabinose-inducible promoter (pBAD-ntrC), NtrC was capable of supporting the growth of the ΔntrC strain. Since the phosphorylation state of a RR likely determines its activity, we mutated the conserved aspartate residue at position 56 (D56) in the REC domain of NtrC to generate a potentially inactive RR (D56A). We found that the construct expressing ntrC with the point mutation D56A (pBAD-ntrCD56A) was unable to complement the growth defect of the ΔntrC strain (Fig. 5B). This finding suggests that the phosphorylation of NtrC is important for its activity as an effector of the nitrogen starvation response in V. cholerae.

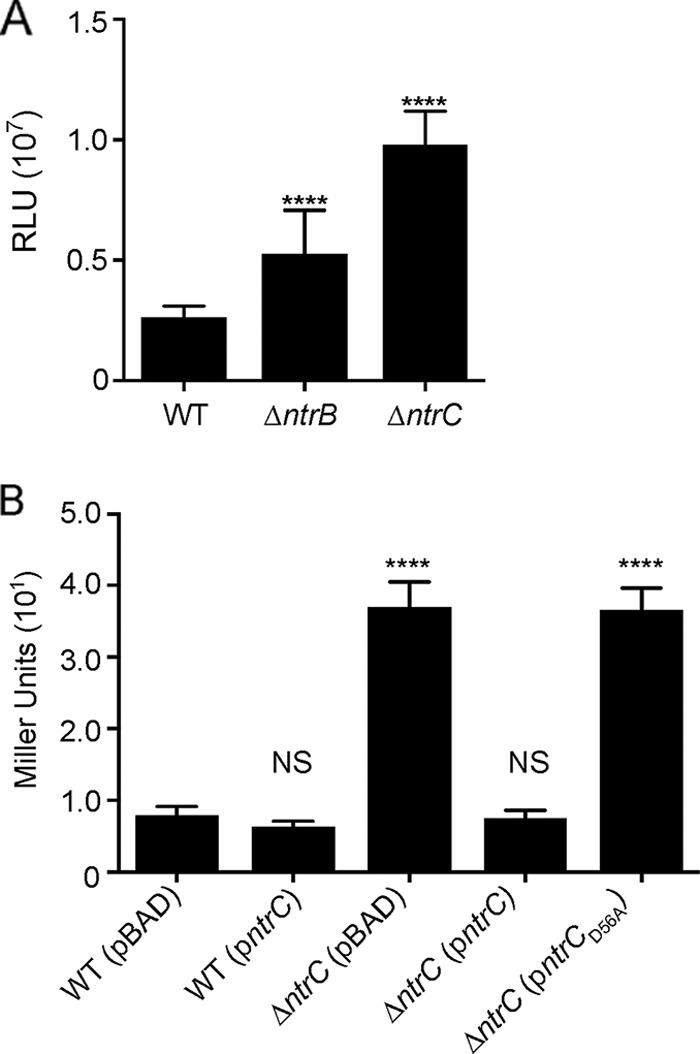

NtrC phosphorylation contributes to vpsL repression.

Since the phosphorylation state of response regulators generally dictates their activity, we examined if the absence of NtrC's cognate histidine kinase, NtrB, affects vpsL expression. The expression levels of PvpsL-lux were increased 100% in the ΔntrB strain and 273% in the ΔntrC strain compared to the wild type (Fig. 6A). We next analyzed the importance of the conserved D56 amino acid residue of NtrC for the negative regulation of vpsL expression. We utilized a reporter strain with PvpsL fused to lacZ on the chromosome (PvpsL-lacZ) and analyzed vpsL expression using β-galactosidase production as a readout (Fig. 6B). When ntrC was overexpressed from a pBAD plasmid in the parental strain, we saw no significant changes in vpsL expression compared to the wild type carrying the empty vector (pBAD). A 363% increase in vpsL expression was observed in the ΔntrC strain compared to the wild type when both strains carried the empty vector. The pBAD-ntrC construct restored vpsL expression in the ΔntrC strain to wild-type levels. This complementation phenotype was lost when NtrC had a D56A point mutation.

FIG 6.

NtrB and aspartate 56 of NtrC contribute to vpsL repression. (A) Expression of PvpsL-luxCADBE (pFY_3406) in the WT, ΔntrB, and ΔntrC strains. The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of RLU obtained from at least three technical replicates from four independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. Expression levels of vpsL in the ΔntrB and ΔntrC strains were compared to that in the WT. (B) β-Galactosidase assay of PvpsL-lacZ reporter strains containing either the empty vector (pBAD) or a vector expressing ntrC (pBAD-ntrC) or ntrCD56A (pBAD-ntrCD56A) under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. Cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with 0.1% arabinose to mid-exponential phase. The graph represents the averages and standard deviations of Miller units obtained from four technical replicates from two biological replicates. The expression levels of vpsL in all strains were compared to that in the WT (pBAD). ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test was performed for multiple-comparison analysis. ****, adjusted P value of <0.0001; NS, not significant.

Together, these results suggest that the phosphorylation of NtrC is important for repressing vpsL expression. The deletion of ntrC or the presence of an ntrC variant with a D56A point mutation has a more profound effect on vpsL expression than does the deletion of ntrB, which suggests that additional factors contribute to NtrC phosphorylation and/or activity under the conditions tested.

NtrC regulates the expression of glnA but not vpsL in a nitrogen source-dependent manner.

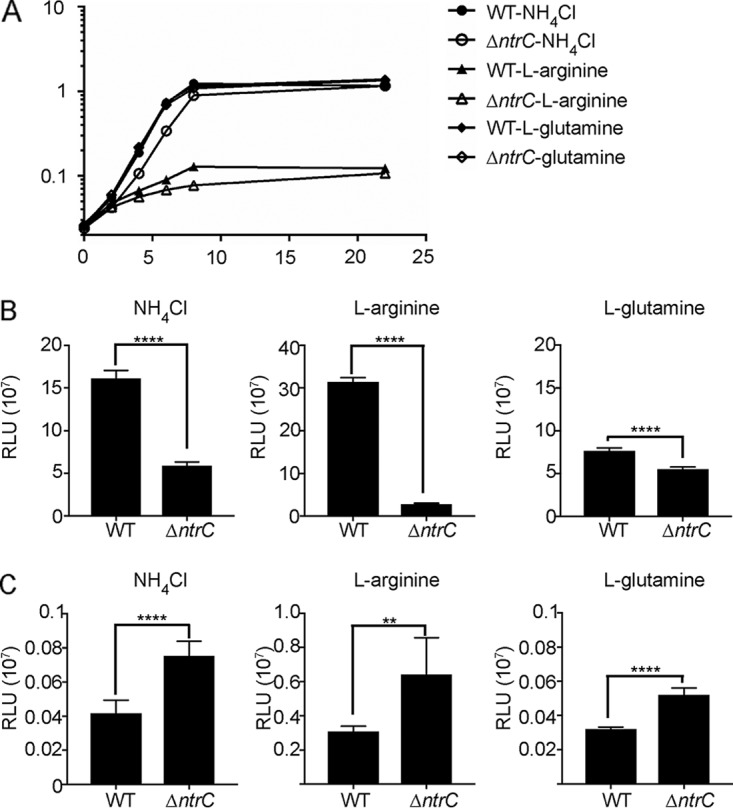

The activity of canonical NtrC orthologues is modulated by nitrogen availability; hence, we hypothesized that vpsL expression would respond to the type of nitrogen source present in the growth medium. To test this possibility, we first monitored the growth of the wild-type and ΔntrC strains in M9 minimal medium supplemented with either NH4Cl (0.1%), l-arginine (100 mM), or l-glutamine (100 mM) as the sole nitrogen source (Fig. 7A). We observed that the levels of growth of the wild-type strain in the presence of NH4Cl or l-glutamine were indistinguishable. However, the use of l-arginine as the sole nitrogen source markedly reduced the growth of the wild type. The ΔntrC strain showed a decrease in growth relative to the wild type when NH4Cl or l-arginine was used as the sole nitrogen source.

FIG 7.

NtrC affects growth with different nitrogen sources and modulates glnA and vpsL expression in V. cholerae. (A) Growth curves of the wild-type and ΔntrC strains grown in defined M9 medium supplemented with 0.1% NH4Cl, 100 mM l-arginine, or 100 mM l-glutamine as the only nitrogen source. The graph represents the means and standard deviations of data for two technical replicates from two biological replicates. (B and C) Expression of PglnA-luxCADBE (B) and PvpsL-luxCADBE (C) in the WT and ΔntrC strains grown for 4 h in the presence of 0.1% NH4Cl, 100 mM l-arginine, or 100 mM l-glutamine as the sole nitrogen source. The graphs represent the averages and standard deviations of RLU obtained from four technical replicates from two independent biological samples. RLU are reported in luminescence counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. Pairwise analysis was performed by using a two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch's correction. **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

As a proxy for NtrC activation, we analyzed the induction of glnA, encoding glutamine synthetase, in cells growing in the presence of the above-mentioned nitrogen sources. We first generated a transcriptional fusion of the regulatory region of glnA with the lux reporter (PglnA-lux) and then compared glnA expression levels between the wild-type and ΔntrC strains grown in the presence of different nitrogen sources. The expression of PglnA-lux in the ΔntrC strain decreased ∼63% when NH4Cl was used as the sole nitrogen source, ∼91% when l-arginine was used as the sole nitrogen source, and ∼28% when l-glutamine was used as the sole nitrogen source, compared to the wild type under the same conditions. These results suggest that NtrC is important for the activation of glnA expression, especially in cells growing with a poor nitrogen source (Fig. 7B).

We next evaluated vpsL expression (PvpsL-lux) in cells growing under the same conditions as those indicated above. The expression of vpsL in the ΔntrC strain was increased ∼80%, ∼108%, and ∼62% when NH4Cl, l-arginine, and l-glutamine were used as the sole nitrogen sources, respectively, compared to the wild type under the same conditions. We hypothesized that the vpsL expression level would be lower with poor nitrogen sources due to NtrC activation. Surprisingly, we observed the opposite: vpsL expression in the presence of l-arginine showed a 637% increase compared to growth in NH4Cl and an 859% increase compared to growth in the presence of l-glutamine as the sole nitrogen source. This result suggests that the regulation of vpsL by different nitrogen sources is more complex than anticipated and not dependent solely on NtrC activation.

DISCUSSION

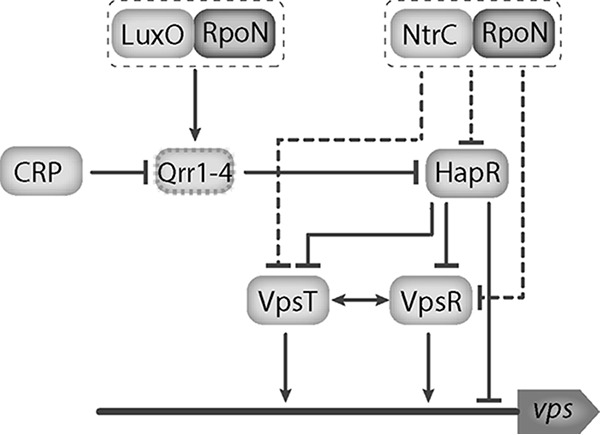

In V. cholerae, the alternative sigma factor RpoN regulates the expression of genes involved in a variety of cellular processes, including, but not limited to, nitrogen assimilation, motility, quorum sensing, and the type VI secretion system (29–31). In this study, we determined the regulatory role of the NtrC family RRs in biofilm formation and the expression of vps genes. RpoN, together with LuxO, regulates the abundance of HapR in response to quorum-sensing signals. This regulation is indirect and involves the activation of the small regulatory RNAs qrr1 to qrr4 by LuxO. These small RNAs block the translation of hapR mRNA at a low cell density (28). The regulatory role of the quorum-sensing master regulator, HapR, in biofilm formation is well documented (6, 7, 32–34). We determined that HapR levels are higher in the ΔrpoN strain, suggesting that the decreased biofilm formation in the absence of RpoN and LuxO is due mainly to the inhibition of the transcription of qrr1 to qrr4 and, in turn, the increased accumulation of HapR. We found that the absence of FlrC and NtrC resulted in increased biofilm formation. Increased vpsL expression in the absence of NtrC depends on RpoN regardless of the presence of HapR (Fig. 8). From a systems biology perspective, RpoN is a highly interconnected node that can regulate a variety of processes through its interaction with specific activator partners. The abundance of RpoN and its specific coactivators can perhaps dictate the outcome of the response to environmental perturbations. Previous work has demonstrated that RpoN acts as a positive regulator of vps. Here we provided genetic evidence suggesting that RpoN can act as a positive or negative regulator of vps depending on the RpoN activator present. In this study, we focused only on the impact of the NtrC class of bEBPs on vps expression; it is possible that there is competition for RpoN availability and that the absence of ntrC results in an increased availability of RpoN, thereby allowing another RpoN-dependent regulator to positively impact levels of vps. Thus, further investigation of the role of sigma factor competition and the mechanism of NtrC-mediated vps regulation is warranted.

FIG 8.

Model of RpoN-dependent regulation of vps. RpoN is a highly interconnected node that can regulate a variety of processes through its interaction with specific activator partners. In response to quorum-sensing signals, LuxO interacts with RpoN to positively regulate the small regulatory RNAs qrr1-4, which block the translation of hapR mRNA at a low cell density. HapR is the quorum-sensing master regulator and negatively regulates vps expression through both direct regulation and the repression of the master biofilm regulators VpsR and VpsT. We demonstrate that NtrC acts as a negative regulator of vps, likely through its repression of vpsR and vpsT, and this regulatory input is dependent on the presence of RpoN. Additionally, it appears that NtrC has a modest negative impact on HapR levels. Solid lines represent direct interactions, and dashed lines indicate indirect interactions.

NtrC from V. cholerae is ∼70% identical to NtrC from E. coli; this, together with data from an early study on RpoN-dependent regulators (30), suggests that in V. cholerae, NtrC is a regulator of nitrogen metabolism. Nitrogen acquisition is of great importance during the V. cholerae life cycle, and it has been reported that chitin, mucin, and nucleosides can be used as nitrogen sources by V. cholerae (35–37). Furthermore, nitrogen limitation leads to glycogen accumulation in V. cholerae, which was found to be important for persistence and transmission (38). Given the central role of NtrC in the regulation of nitrogen metabolism in other organisms, it is pertinent to better understand its involvement in different physiological processes where nitrogen availability dictates the fate of V. cholerae. Here we show that NtrC limits biofilm formation and downregulates the expression levels of a structural matrix gene, vpsL, as well as genes encoding biofilm regulators, such as vpsR, vpsT, and hapR (Fig. 1 and 2). None of these genes seem to have promoters with signals recognized by RpoN (data not shown), which suggests that regulation by NtrC is indirect. Our results revealed a negative effect of NtrC on HapR accumulation; it is unknown if this regulation occurs through the RpoN-LuxO-Qrr regulatory cascade or in a different pathway. HapR and Crp are the main negative regulators of biofilm formation in V. cholerae. We observed a 292% increase in vpsL expression in the ΔntrC strain compared to the wild type but only 35% and 20% increases in the ΔntrC ΔhapR and ΔntrC Δcrp strains compared to the single ΔhapR and Δcrp mutants. Given the difference in the magnitudes of induction of vpsL, we cannot disregard the possibility of a genetic interaction between ntrC, hapR, and crp. For instance, an interaction between hapR and crp was proposed previously (8, 9), and here we report that the absence of NtrC has a modest effect on hapR expression. Undoubtedly, the balance between these regulators is crucial for controlled biofilm formation and may play a role in processes such as biofilm dispersal and transmission.

We observed the NtrC-repressive effect on biofilms in rich medium (lysogeny broth [LB]), suggesting that nitrogen limitation is not a prerequisite for NtrC activation and perhaps that basal levels of phosphorylation of NtrC by phosphodonors, such as acetyl phosphate, are sufficient to exert NtrC-dependent repression of biofilm formation. Our results suggest that growth with l-arginine as the sole nitrogen source results in nitrogen limitation. Under these conditions, NtrC is expected to be activated by NtrB-mediated phosphorylation; therefore, we predicted that the level of expression of vpsL would be lower than that under nitrogen-replete conditions. Interestingly, opposite of our prediction, we found that the expression of vpsL was induced under these conditions (Fig. 7). l-Arginine has been shown to promote c-di-GMP accumulation and cellulose production in S. Typhimurium (39), and it is possible that V. cholerae cells also respond to the presence of l-arginine by increasing c-di-GMP levels independently from NtrC and, as a consequence, vpsL expression. Our results suggest that nitrogen limitation may positively regulate vpsL expression independently from NtrC and that other vps regulators may play a role under these conditions.

The nitrogen-related phosphotransfer system (PTSNtr) has been shown to sense nitrogen limitation in Escherichia coli and Caulobacter crescentus (40, 41). For V. cholerae, two nitrogen-specific enzyme IIA (EIIANtr) homologs, but not the upstream members of the PTSNtr, were reported to repress vpsL expression (42). Interestingly, the effect of EIIANtr proteins on biofilm formation occurs in cells grown in LB but not in M9 minimal medium (42). It is important to note that the role of the V. cholerae PTSNtr has not been studied in great depth under conditions of nitrogen limitation. Interestingly, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, unphosphorylated EIIANtr also acts as a repressor of biofilm formation (43). We observed that NtrC regulates biofilm formation in LB and vpsL expression both in LB and M9 minimal medium, regardless of the nitrogen source available. It would be informative to further characterize if there is a connection between the regulatory effects of NtrC and EIIANtr on biofilm formation.

In Vibrio vulnificus, the NtrC orthologue has been shown to upregulate the expression of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and exopolysaccharide (EPS)-related genes (44, 45) when grown in minimal medium under nitrogen limitation. Additionally, NtrC in Burkholderia cenocepacia also appears to positively regulate EPS production (46). Further studies of the mechanism of biofilm regulation by NtrC in these organisms, as well as in V. cholerae, where NtrC has an opposite role, would allow us to better understand the factors that shape the evolution of related regulatory pathways and their outcomes in specific biological systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Escherichia coli CC118λpir strains were used for DNA manipulation, and E. coli S17-1λpir strains were used for conjugation with V. cholerae. In-frame deletion mutants of V. cholerae were generated as described previously (32). All V. cholerae and E. coli strains were grown aerobically, at 30°C and 37°C, respectively, unless otherwise noted. Cells were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl [pH 7.5]), unless otherwise stated. LB agar medium contains 1.5% (wt/vol) granulated agar (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Concentrations of antibiotics used were as follows: ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, rifampin at 100 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol at 5 μg/ml for V. cholerae and 20 μg/ml for E. coli. Cells were also grown in M9 minimal medium (0.6% Na2HPO4, 0.3% KH2PO4, 0.5% NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose) supplemented with 1× minimal essential medium vitamins (10 ml/liter; Gibco, Rockford, IL) and either 0.1% NH4Cl or 100 mM the following l-amino acids: arginine and glutamine.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Reference or source(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| CC118λpir | Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rpsE rpoB argE(Am) recA1 λpir | 53 |

| S17-1λpir | Tpr Smr recA thi pro (rK− mK+) RP4::2-Tc::Mu-Km Tn7 λpir | 54 |

| K-12 (BW28357) | lacIp4000(lacIq) rrnB3 ΔlacZ4787 hsdR514 Δ(araBAD)567 Δ(rhaBAD)568 rph-1 | 55 |

| K-12ΔntrBC (BW30011) | lacIp4000(lacIq) rrnB3 ΔlacZ4787 hsdR514 Δ(araBAD)567 Δ(rhaBAD)568 rph-1 Δ(ntrB-ntrC)1318 | 55 |

| V. cholerae | ||

| FY_VC_0001 | Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor A1552; wild type; Rifr | 6 |

| FY_VC_0616 | PvpsL-lacZ; Rifr | 27 |

| FY_VC_2272 | ΔVC0665 (vpsR) | 4 |

| FY_VC_0192 | ΔVC1021 (luxO) | 47 |

| FY_VC_7998 | ΔVC1522 | 47 |

| FY_VC_8243 | ΔVC1926 (dctD-1) | 47 |

| FY_VC_6286 | ΔVC2135 (flrC) | 47 |

| FY_VC_6289 | ΔVC2749 (ntrC) | 47 |

| FY_VC_8245 | ΔVCA0142 (dctD-2) | 47 |

| FY_VC_2407 | ΔVC0665 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_8068 | ΔVC1021 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_8070 | ΔVC1522 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_8319 | ΔVC1926 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_8072 | ΔVC2135 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_7061 | ΔVC2749 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_8321 | ΔVCA0142 mTn7-gfp Rifr Gmr | This study |

| FY_VC_7058 | ΔVC2748 (ntrB) | This study |

| FY_VC_7057 | ΔntrC ΔvpsR | This study |

| FY_VC_0099 | ΔvpsT | 5 |

| FY_VC_7051 | ΔntrC ΔvpsT | This study |

| FY_VC_7936 | ΔVC2529 (rpoN) | This study |

| FY_VC_7304 | ΔntrC ΔrpoN | This study |

| FY_VC_0178 | ΔhapR | This study |

| FY_VC_7054 | ΔntrC ΔhapR | This study |

| FY_VC_2326 | Δcrp | 9 |

| FY_VC_7056 | ΔntrC Δcrp | This study |

| FY_VC_13619 | ΔrpoN ΔhapR | This study |

| FY_VC_13621 | ΔrpoN ΔntrC ΔhapR | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGP704sacB28 | pGP704 derivative; mob-oriT sacB Apr | G. Schoolnik |

| pFY-1422 | pGP704-sacB28::ΔVC2748; Apr | This study |

| pBBRlux | luxCDABE-based promoter fusion vector; Cmr | 28 |

| pFY-0950 | pBBRlux vpsL promoter; Cmr | 56 |

| pFY-1326 | pBBRlux glnA promoter; Cmr | This study |

| pFY-0989 | pBBRlux vpsR promoter; Cmr | This study |

| pFY-0988 | pBBRlux vpsT promoter; Cmr | This study |

| pFY-1049 | pBBRlux hapR promoter; Cmr | This study |

| pBAD/myc-His-B | Arabinose-inducible expression vector with C-terminal myc epitope and six-His tags | Invitrogen |

| pFY-1648 | pBAD/myc-His-B::ntrBCVCa; Apr | This study |

| pFY-1351 | pBAD/myc-His-B::ntrC; Apr | This study |

| pFY-1349 | pBAD/myc-His-B::ntrCD56A; Apr | This study |

| pUX-BF13 | oriR6K helper plasmid; mob-oriT; provides the Tn7 transposition function in trans; Apr | 57 |

| pMCM11 | pGP704::mTn7-gfp; Gmr Apr | M. Miller and G. Schoolnik |

VC, V. cholerae.

DNA manipulations and generation of in-frame deletion mutants and gfp-tagged strains.

An overlapping PCR method was used to generate in-frame deletion constructs using previously described methods (32). The generation of deletions by double recombination was performed as described previously (47, 48). V. cholerae wild-type and mutant strains were tagged with the green fluorescent protein gene (gfp) as described previously (49). The gfp-tagged V. cholerae strains were verified by PCR and examined in flow cell experiments.

Flow cell experiments and confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Flow cells were inoculated by normalizing cultures of gfp-tagged V. cholerae strains grown overnight to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.02 and injecting cells into an Ibidi m-Slide VI0.4 instrument (catalogue number 80601; Ibidi LLC, Verona, WI). After inoculation, the bacteria were allowed to adhere at room temperature for 1 h with no flow. Next, a flow of 2% (vol/vol) LB (0.2 g/liter tryptone, 0.1 g/liter yeast extract, 1% NaCl) was initiated at a rate of 7.5 ml/h. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of the biofilms were captured with an LSM 5 Pascal system (Zeiss, Jena, Germany), using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 543 nm. Three-dimensional images of the biofilms were reconstructed by using Imaris software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland) and quantified by using COMSTAT (50).

Luminescence assay.

Cultures of V. cholerae cells grown overnight in LB were diluted 1:1,000 in LB containing chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) or washed twice in M9 minimal medium without nitrogen and diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 in M9 minimal medium containing different nitrogen sources and chloramphenicol (2.5 μg/ml). Cultures grown in LB at 30°C were harvested at mid-exponential phase (OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4) for luminescence readings. Cultures grown in M9 minimal medium at 30°C were harvested for luminescence reading after reaching an OD600 of ∼0.1 in the presence of NH4Cl and l-glutamine or ∼0.06 in the presence of l-arginine. Luminescence was measured by using a PerkinElmer Victor3 multilabel counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and is reported as relative light units (RLU) in counts per minute per milliliter per OD600. Assays were repeated with at least two biological replicates. Four technical replicates were measured for all assays.

Western blotting of HapR.

Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600), and 25 ml of the culture was then harvested and lysed in 5 ml of 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 4 mg of DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO). The protein concentration was estimated with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Thirty micrograms of protein was loaded and resolved by electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Immunoblotting was performed by using a polyclonal anti-HapR antibody (51) or purified anti-E. coli RNA polymerase α antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Proteins were detected by chemiluminescence using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and SuperSignal West Pico Plus chemiluminescent substrate according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA).

c-di-GMP measurements.

Extraction of c-di-GMP was performed as described previously (52). Cultures were grown in LB to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4, and 40 ml was harvested for c-di-GMP quantification. The amount of c-di-GMP was calculated by interpolation using a standard curve generated from pure c-di-GMP suspended in 184 mM NaCl (Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany). The c-di-GMP levels were expressed as picomoles per milligram of total protein. The protein concentration was determined from 4 ml of culture, cells were lysed in 1 ml of 2% SDS, and total protein was estimated with a BCA assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Each c-di-GMP quantification experiment was performed with six biological replicates. Levels of c-di-GMP were compared between the samples by using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Growth on minimal medium.

One milliliter of cultures grown overnight was harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 5 μl of the resuspension mixture was spotted onto defined M9 agar containing either 100 mM l-serine or l-arginine as the only nitrogen source. The plates were incubated at 30°C for V. cholerae and at 37°C for E. coli for 24 h. Images were taken by using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

β-Galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed by using exponentially grown cultures. V. cholerae cells were grown overnight (18 to 20 h) aerobically in LB containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin. Cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:200 in fresh LB medium with or without arabinose and grown aerobically to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4. The cells were then diluted again 1:200 in fresh LB with or without arabinose, grown aerobically to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4, and immediately harvested for assays. The β-galactosidase assays were carried out with MultiScreen 96-well microtiter plates fitted onto a MultiScreen filtration system (Millipore, Billerica, MA), using a previously described procedure (49).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jun Zhu for providing HapR antibody.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI114261 and R01AI102584 to F.H.Y.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00025-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Teschler JK, Zamorano-Sánchez D, Utada AS, Warner CJA, Wong GCL, Linington RG, Yildiz FH. 2015. Living in the matrix: assembly and control of Vibrio cholerae biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:255–268. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yildiz FH, Schoolnik GK. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:4028–4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong JCN, Syed KA, Klose KE, Yildiz FH. 2010. Role of Vibrio polysaccharide (vps) genes in VPS production, biofilm formation and Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis. Microbiology 156:2757–2769. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yildiz FH, Dolganov NA, Schoolnik GK. 2001. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPS ETr-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J Bacteriol 183:1716–1726. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1716-1726.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J Bacteriol 186:1574–1578. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1574-1578.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yildiz FH, Liu XS, Heydorn A, Schoolnik GK. 2004. Molecular analysis of rugosity in a Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor phase variant. Mol Microbiol 53:497–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters CM, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. 2008. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J Bacteriol 190:2527–2536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01756-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang W, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2007. The cyclic AMP receptor protein modulates colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:7482–7487. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01564-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong JCN, Yildiz FH. 2008. Interplay between cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein and cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 190:6646–6659. doi: 10.1128/JB.00466-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Ayala JC, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2012. The histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) is a repressor of Vibrio cholerae exopolysaccharide biosynthesis (vps) genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2482–2488. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07629-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilecen K, Yildiz FH. 2009. Identification of a calcium-controlled negative regulatory system affecting Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Environ Microbiol 11:2015–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratt JT, McDonough E, Camilli A. 2009. PhoB regulates motility, biofilms, and cyclic di-GMP in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 191:6632–6642. doi: 10.1128/JB.00708-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sultan SZ, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. 2010. The PhoB regulatory system modulates biofilm formation and stress response in El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 302:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 50:101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tischler AD, Camilli A. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 53:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilecen K, Fong JCN, Cheng A, Jones CJ, Zamorano-Sánchez D, Yildiz FH. 2015. Polymyxin B resistance and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae are controlled by the response regulator CarR. Infect Immun 83:1199–1209. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02700-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenz DH, Miller MB, Zhu J, Kulkarni RV, Bassler BL. 2005. CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 58:1186–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teschler JK, Cheng AT, Yildiz FH. 2017. The two-component signal transduction system VxrAB positively regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 199:e00139-. doi: 10.1128/JB.00139-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush M, Dixon R. 2012. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of σ54-dependent transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galperin MY. 2006. Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: diversity of output domains and domain combinations. J Bacteriol 188:4169–4182. doi: 10.1128/JB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss DS, Batut J, Klose KE, Keener J, Kustu S. 1991. The phosphorylated form of the enhancer-binding protein NtrC has an ATPase activity that is essential for activation of transcription. Cell 67:155–167. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90579-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirschman J, Wong PK, Sei K, Keener J, Kustu S. 1985. Products of nitrogen regulatory genes ntrA and ntrC of enteric bacteria activate glnA transcription in vitro: evidence that the ntrA product is a sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:7525–7529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watnick PI, Lauriano CM, Klose KE, Croal L, Kolter R. 2001. The absence of a flagellum leads to altered colony morphology, biofilm development and virulence in Vibrio cholerae O139. Mol Microbiol 39:223–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vance RE, Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. 2003. A constitutively active variant of the quorum-sensing regulator LuxO affects protease production and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 71:2571–2576. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2571-2576.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correa NE, Lauriano CM, McGee R, Klose KE. 2000. Phosphorylation of the flagellar regulatory protein FlrC is necessary for Vibrio cholerae motility and enhanced colonization. Mol Microbiol 35:743–755. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raychaudhuri S, Jain V, Dongre M. 2006. Identification of a constitutively active variant of LuxO that affects production of HA/protease and biofilm development in a non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae O110. Gene 369:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shikuma NJ, Fong JCN, Odell LS, Perchuk BS, Laub MT, Yildiz FH. 2009. Overexpression of VpsS, a hybrid sensor kinase, enhances biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 191:5147–5158. doi: 10.1128/JB.00401-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klose KE, Mekalanos JJ. 1998. Distinct roles of an alternative sigma factor during both free-swimming and colonizing phases of the Vibrio cholerae pathogenic cycle. Mol Microbiol 28:501–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klose KE, Novik V, Mekalanos JJ. 1998. Identification of multiple sigma54-dependent transcriptional activators in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 180:5256–5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong TG, Mekalanos JJ. 2012. Characterization of the RpoN regulon reveals differential regulation of T6SS and new flagellar operons in Vibrio cholerae O37 strain V52. Nucleic Acids Res 40:7766–7775. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim B, Beyhan S, Meir J, Yildiz FH. 2006. Cyclic-di-GMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 60:331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev Cell 5:647–656. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srivastava D, Harris RC, Waters CM. 2011. Integration of cyclic di-GMP and quorum sensing in the control of vpsT and aphA in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 193:6331–6341. doi: 10.1128/JB.05167-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meibom KL, Li XB, Nielsen AT, Wu C-Y, Roseman S, Schoolnik GK. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae chitin utilization program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:2524–2529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308707101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mondal M, Nag D, Koley H, Saha DR, Chatterjee NS. 2014. The Vibrio cholerae extracellular chitinase ChiA2 is important for survival and pathogenesis in the host intestine. PLoS One 9:e103119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gumpenberger T, Vorkapic D, Zingl FG, Pressler K, Lackner S, Seper A, Reidl J, Schild S. 2016. Nucleoside uptake in Vibrio cholerae and its role in the transition fitness from host to environment. Mol Microbiol 99:470–483. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourassa L, Camilli A. 2009. Glycogen contributes to the environmental persistence and transmission of Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 72:124–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills E, Petersen E, Kulasekara BR, Miller SI. 2015. A direct screen for c-di-GMP modulators reveals a Salmonella Typhimurium periplasmic l-arginine-sensing pathway. Sci Signal 8:ra57. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee C-R, Park Y-H, Kim M, Kim Y-R, Park S, Peterkofsky A, Seok Y-J. 2013. Reciprocal regulation of the autophosphorylation of enzyme INtr by glutamine and α-ketoglutarate in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 88:473–485. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ronneau S, Petit K, De Bolle X, Hallez R. 2016. Phosphotransferase-dependent accumulation of (p)ppGpp in response to glutamine deprivation in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat Commun 7:11423. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houot L, Chang S, Pickering BS, Absalon C, Watnick PI. 2010. The phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation through multiple independent pathways. J Bacteriol 192:3055–3067. doi: 10.1128/JB.00213-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cabeen MT, Leiman SA, Losick R. 2016. Colony-morphology screening uncovers a role for the Pseudomonas aeruginosa nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system in biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 99:557–570. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim H-S, Lee M-A, Chun S-J, Park S-J, Lee K-H. 2007. Role of NtrC in biofilm formation via controlling expression of the gene encoding an ADP-glycero-manno-heptose-6-epimerase in the pathogenic bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol 63:559–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim H-S, Park S-J, Lee K-H. 2009. Role of NtrC-regulated exopolysaccharides in the biofilm formation and pathogenic interaction of Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol 74:436–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Lardi M, Pedrioli A, Eberl L, Pessi G. 2017. NtrC-dependent control of exopolysaccharide synthesis and motility in Burkholderia cenocepacia H111. PLoS One 12:e0180362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng AT, Ottemann KM, Yildiz FH. 2015. Vibrio cholerae response regulator VxrB controls colonization and regulates the type VI secretion system. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004933. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fong JCN, Yildiz FH. 2007. The rbmBCDEF gene cluster modulates development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 189:2319–2330. doi: 10.1128/JB.01569-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fong JCN, Karplus K, Schoolnik GK, Yildiz FH. 2006. Identification and characterization of RbmA, a novel protein required for the development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm structure in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 188:1049–1059. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.1049-1059.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heydorn A, Nielsen AT, Hentzer M, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Ersbøll BK, Molin S. 2000. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146(Part 1):2395–2407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Z, Hsiao A, Joelsson A, Zhu J. 2006. The transcriptional regulator VqmA increases expression of the quorum-sensing activator HapR in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 188:2446–2453. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2446-2453.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu X, Beyhan S, Lim B, Linington RG, Yildiz FH. 2010. Identification and characterization of a phosphodiesterase that inversely regulates motility and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 192:4541–4552. doi: 10.1128/JB.00209-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis KN. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Lorenzo V, Timmis KN. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol 235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou L, Lei X-H, Bochner BR, Wanner BL. 2003. Phenotype microarray analysis of Escherichia coli K-12 mutants with deletions of all two-component systems. J Bacteriol 185:4956–4972. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4956-4972.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shikuma NJ, Fong JCN, Yildiz FH. 2012. Cellular levels and binding of c-di-GMP control subcellular localization and activity of the Vibrio cholerae transcriptional regulator VpsT. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002719. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bao Y, Lies DP, Fu H, Roberts GP. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167–168. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90604-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.